Abstract

Background:

The experience of stress in patients with cancer through helplessness and the suppression of emotions correlates with unfavorable disease prognosis. Significant distress can reduce survival probability as well as subjectively perceived poor quality of life. Currently, there are few data on psychological stress in patients with renal cancer and most studies focus on survival time. The aim of the study was to evaluate the psychosocial stress of patients with renal cancer with screening questionnaires for an inpatient psychosocial treatment program.

Methods:

Patients undergoing inpatient surgical or medical treatment for renal cancer were prospectively assessed for psychosocial stress with two standardized stress screening questionnaires used for the identification of the need for psychosocial care [NCCN Distress Thermometer (NCCN-DT), Hornheider Screening Instrument (HSI)].

Results:

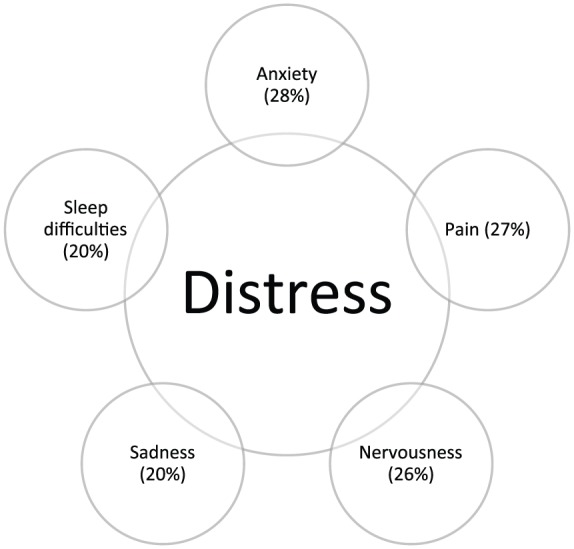

Seventy-four patients with a mean age of 65 years were assessed. The average NCCN-DT score was 4.8 (scale of 0–10) and did not correlate with tumor stage, sex or prognosis. According to the DT results, 27% of patients were in need of psychosocial care which was significantly higher than the self-reported need. The main stressors were anxiety (32%), pain (27%), nervousness (26%), sadness, worry and sleeping difficulties (20%).

Conclusions:

There is a significant number of patients with renal cancer with increased psychological distress and a consecutive need for psychosocial care. This is underreported and largely unrecognized by patients as well as physicians and nurses. Easy-to-use assessment tools can be very helpful in identifying patients in need and this information can be used to implement psychological support and thus improve patient care.

Keywords: renal cell cancer, psychosocial stress, distress, psychooncology

Introduction

Despite improved cancer treatment and cancer care, significantly more people die of cancer in Germany today than 30 years ago (193,000 cancer deaths in 1980, 224,000 cancer deaths in 2014). The reason for this seemingly contradictory development is related the increased life expectancy in an ageing society and the increasing cancer incidence which in itself is related to age. The incidence of cancer has almost doubled since the 1970s. The number of cancer cures has also increased. Currently, there are around 4 million cancer survivors in Germany. The average age of patients dying of cancer is 74 years, which statistically is 4 years higher than it was in 1980.1

In 2013, approximately 14,910 patients were newly diagnosed with renal cancer in Germany (9360 men, 5500 women) while 4458 died of renal cancer (3358 men, 2100 women).1 A steady increase in renal cancer has been observed for men since the 1990s, while there has been a distinct decline for women since 2009. The mean age of diagnosis is 68 years for men and 72 years for women. The overall prognosis of renal cancer is relatively favorable, with a relative 5-year survival rate of 76% in men and 78% in women since the majority (about 75%) of renal cancers are diagnosed in early, organ-confined stages (T1/T2) when surgical treatment is likely to be curative.2 Higher incidence and mortality rates for renal cancer are seen in the eastern states of Germany (the area of the former German Democratic Republic) compared with the western regions.1

Patients with cancer are exposed to numerous pressures and may be affected by many limitations. They are threatened by the malignancy itself and also by potential side effects of the treatment. Important psychological stress factors are the uncertainty of treatment outcome, the experience of a direct threat to life, the potential changes in self image, physical functions and their family as well as social roles. Mental stress can include anxiety and depression, but also more nonspecific psychosocial stress (distress).

There are not a lot of data on the specific psychooncological problems of patients with renal cancer as most studies only investigate survival.3,4 However, stress in patients with cancer correlates with prognosis, reduced survival probability, an increase in cancer-specific mortality, poor as well as reduced quality of life.3 Patients with renal cell carcinoma have an increased suicide rate. Male sex and distant disease were found to be associated with odds of suicide among patients with kidney cancer.5

In 2014, we initiated a project in our department aiming to accurately evaluate distress in patients with urology cancer with a view to identifying patients in need of psychosocial support. In this study, we assessed psychosocial stress in patients with renal cancer using screening questionnaires.

Patients and methods

All consecutive patients with renal cancer treated as inpatients in our department over a period of 22 months were included, irrespective of tumor stage (localized versus advanced) or type or intent of treatment (palliative versus curative). Patients were recruited either during the first outpatient consultation in preparation for inpatient surgery or during the admission. All patients were native German speakers or sufficiently fluent in German and unaffected by mental or cognitive disorders.

Patients were asked to fill in two validated questionnaires assessing psychosocial stress and psychosocial need for care [the Hornheider Screening Instrument (HSI) and the NCCN Distress Thermometer (NCCN-DT)]. The HSI had been developed for the fast and reliable identification of patients in need of psychosocial care at first contact.6 The NCCN-DT was developed as a research instrument in psychooncology. It is also a tool that can be used in cancer clinics to detect clinically significant distress and is an ultrashort screening instrument aiming to capture the extent and cause of existing psychosocial stress (distress). The NCCN-DT is a screening instrument suitable for patients with cancer of all stages. It is a self-assessment tool and consists of a visual analogue scale in the form of a thermometer, which ranges from 0 (‘not loaded’) to 10 (‘extreme pressure’). In addition, it includes a list of potential problems with a total of 36 items in five different problem areas: practical (e.g. housing situation), family (e.g. access to children), emotional (e.g. sadness), spiritual (e.g. loss of faith) and physical (e.g. pain). All these items are answered as dichotomous ‘yes’ or ‘no’ options. A value of 5 or higher is considered as an indication of significant stress and the need for psychosocial support.7 With regard to the selection of the questionnaires regarding the urological patient population and the cutoff values, we follow the recommendations of the respective authors. Both questionnaires are suitable for all age groups and tumor entities.6,7

The questionnaires in our study were self administered. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained. The HSI was evaluated by means of the HSI sum value (with a threshold ⩾4 indicating significant stress). For the NCCN-DT a value of 5 or higher indicates significant stress. The data were explored with descriptive statistics (SPSS 22, IBM, USA). Standard descriptive statistics were used to characterize the demographic, clinical and distress variables in the sample. Demographic and medical data (age, sex, stage, treatment, medical history) were obtained from medical records.

Results

Seventy-four patients with renal cancer who underwent surgical (n = 71) or medical treatment (n = 3) were included. Fifty-four were men (73%) and 20 were women (27%) (Table 1). The average patient age was 65 years [standard deviation (SD) 13.1]. A total of 41.9% of patients were under 65 years of age (n = 31) and 58.1% were over 65 years (n = 43). The average rate of self-reported distress level was 4.8 (SD 2.3) (Table 2). In clinical practice, we used a cutoff point of at least 5 for the NCCN-DT to implement psychosocial care. According to the NCCN-DT results, 47.3% of patients had a significant need for psychosocial support. This was in contrast to the self-reported need for support according to the HSI results. This was significantly lower (p < 0.001) than the need as assessed by the NCCN-DT (27% over all age groups versus 7% according to self-reported need in the HSI).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of included patients with renal cell cancer (n = 74).

| Characteristics | Renal cell carcinoma (n = 74) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Mean age (in years) | 65 (SD 13.1) |

| <65 years (%) | 31 (41.9) |

| >65 years (%) | 43 (58.1) |

| Sex | |

| Male (%) | 54 (73) |

| Female (%) | 20 (27) |

| Treatment | |

| Surgery (%) | 71 (91.2) |

| Systemic therapy (%) | 3 (2.8) |

| Tumor stage | |

| pT1 | 38 |

| pT2 | 11 |

| pT3 | 24 |

| pT4 | 1 |

| Metastasis stage | |

| N0/M0 | 71/63 |

| N+/M+ | 3/11 |

| Remission | 63 (+1 stable disease) |

| Recurrence/progression | 7 |

| Cancer-specific death | 3 |

| Mean follow up (in months) | 36 (SD 12.4) |

SD, standard deviation.

Table 2.

All patients with renal cell cancer showed a high stress level independent of tumor and metastasis, disease history, sex and age.

| Impact factors | Distress level (cutoff level ⩾5) |

|---|---|

| Tumor stages | |

| pT1 | 4.5 |

| pT2 | 4.8 |

| pT3 | 5.1 |

| pT4 | 5.0 |

| Metastasis stages | |

| N0/M0 | 4.8/4.6 |

| N+/M+ | 4.2/5.3 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 4.7 |

| Female | 4.9 |

| Age | |

| <65 years | 4.8 |

| ⩾65 years | 4.7 |

| Treatment | |

| Surgery | 4.8 |

| Chemotherapy | 4.3 |

| Progression | |

| No progression | 4.7 |

| Progression | 5.0 |

| Cancer-specific death | |

| Survival | 4.7 |

| Cancer-specific death | 5.0 |

There was a low positive correlation between the scores of the HSI and those of the NCCN-DT (Spearman r² = 0.567). Stratified by tumor stage, there was no significant difference in the need for psychosocial care between groups in the NCCN-DT (pT1: 4.5, pT2: 4.8, pT3: 5.1, pT4: 5.0), nor was there a difference in this cohort between patients with localized or metastatic disease (N0/M0 4.8/4.6 versus N+/M+: 4.2/5.3). Male and female patients showed similar stress levels (men 4.7 versus women 4.9) and there were also no significant differences between age groups (<65 years 4.8, >65 years 4.7). Also, whether the disease seemed to be progressive or not did not significantly affect the average stress level (no progression 4.7 versus with progression 5) (Table 2).

The need for support was significantly related to the acceptance of an offer for psychosocial help (p < 0.001), that is, patients with an elevated distress level who did not want support were also unlikely to accept an offer of psychosocial counselling. The main identified stressors were anxiety (28%), pain (27%), nervousness (26%), sadness (20%), sorrow (20%) and sleep difficulties (20%) (Figure 1). Except for pain, somatic stressors were of secondary importance.

Figure 1.

Main stressors regardless of tumor stage, age, metastasis or sex.

There was a difference in findings when the survey was conducted. There was a certain increase in the preinterventional phase (before surgery, before starting systemic therapy or before staging examination). During systemic therapy, the psychosocial distress becomes less when there is no pronounced symptom burden (physical or mental).

Discussion

A cancer diagnosis is a major burden for those affected, despite improvements in treatment and longer survival times. Complex and long-lasting treatments can obviously lead to psychological and physical stress.8 Maintaining mental and social quality of life is of great importance for patients with cancer. Since the survival of many patients with cancer is progressively prolonged due to treatments, with significant increases in cancer-specific survival, some cancers are almost taking on the character of a chronic disease. The best example of such a chronic cancer illness today is prostate cancer. However, renal cancer has also experienced an ongoing increase in patient survival with many new medical treatment options for metastatic disease available.9 Chronification of an oncological disease entity is likely to increase the need for psychooncological support.

Psychooncological interventions can be effective in coping with the disease and alleviate psychological or psychosomatic symptoms. To what extent this also affects the recovery and survival, however, remains controversial. In many national and international guidelines, psychooncological support is considered to be an integral part of oncological treatment and often requires the certification of oncological centers. Assessing health-related quality of life (HRQoL) following cancer treatment has become part of many standardized treatment protocols. The psychological morbidity of patients with urological tumors has been confirmed many times.10–12 A multicenter study identified psychosocial stress requiring intervention in about 30% of patients.11

Beisland and colleagues developed an European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC)-compatible renal-cancer-specific HRQoL questionnaire with five domains: general symptomatic, general functional, disease-specific symptoms (flank pain, hematuria, flank edema, urinary tract infection), sexuality and one about weight loss or gain. From this, 10 renal-cancer-specific HRQoL questions were derived by factor analysis, including four questions related particularly to pain, mobility and social functioning. This disease-specific EORTC Quality of Life (QLQ)-style RCC10 version adds important information about the HRQoL of patients with renal cell cancer.13

In our study, a high proportion of patients reported significant and relevant distress, much higher than the self-reported need for psychosocial support. Common barriers against seeking help include lack of knowledge, living in rural areas and limited access to appropriate outpatient facilities. In an inpatient setting, there is more communication between patients and exchange about coping strategies, a mechanism which can often be observed and should generally be considered valuable.

Along with prolonged survival in many patients with cancer, quality of life strongly influenced by psychosocial factors also seems to have improved.14,15 Spiegel and Kato strongly argue that positive coping strategies supported by psychosocial care improve the chances of survival.16 Thus, the concept of quality of life in patients with cancer plays an ever-increasing role.17,18

A high prevalence of emotional distress of 35–45% has repeatedly been reported for patients with cancer,19,20 whereby the level of distress increases in advanced disease.16 Our study confirms this high prevalence (47% on the NCCN-DT and 27% in the HSI). There are only a few studies investigating the coping strategies of patients with a cancer diagnosis21 and there are few data on psychosocial stress in renal cancer, which is a highly aggressive disease that causes no symptoms in the early stages and today is most often diagnosed incidentally.

Mehnert and colleagues reported a 4-week prevalence of 36.4% of mental comorbidity in patients with renal cancer, which was above average in their cohort of patients with different cancer entities (mean 31.8%). In our study we could not identify a specific factor influencing the stress level. Age, sex, treatment, stage or metastasis status did not seem to significantly influence the stress level.22

The awareness of psychosocial stress as an important component disease burden in cancer care has certainly increased.23 It is now accepted that distress affects important treatment-related areas such as treatment adherence,24 satisfaction with care,25,26 length of hospital stay,27 quality of life28–31 and survival time.32–34

Despite the evidence that screening tools can improve the detection of psychosocial distress,35–38 and can facilitate communication about psychosocial issues between professionals and patients,39–42 the direct effect on the patients’ quality of life is still uncertain.43 Therefore, screening for distress still remains somewhat controversial.44 The current consensus seems to be that screening for distress has a benefit for quality of care. The success of any screening is related to the inclusion of unmet needs, the acceptability of the screening, and the acceptance and availability of psychosocial caregivers.45,46

The aim of our study was to demonstrate the importance of an understanding of the difficulties, challenges and developmental tasks that patients with renal cancer face as the specific psychosocial issues of these patients have not been well studied. Patients with renal cancer are typically elderly and psychosocial distress in elderly patients is often underdiagnosed and undertreated.

There are several limitations of our study. It contains a relatively small number of patients recruited over a limited period of time. There is probably an underreporting of emotional distress factors in our cohort, which is typical for this age group in Germany. The degree of underreporting seen in our patients may be different in other regional and national settings.

However, our study clearly showed that there is a significant number of patients with renal cancer with increased psychological distress and a consecutive need for psychosocial care. Easy-to-use assessment tools such as the questionnaires we used can be very helpful in identifying patients in need and this information can be used to implement psychological support and thus improve patient care.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Désirée Louise Draeger, Department of Urology, University of Rostock, Ernst-Heydemann-Strasse 6, Schillingallee 35, 18057 Rostock, Germany.

Karl-Dietrich Sievert, Department of Urology, University of Rostock, Rostock, Germany.

Oliver W. Hakenberg, Department of Urology, University of Rostock, Rostock, Germany

References

- 1. Robert-Koch-Institut. Bericht zum Krebsgeschehen in Deutschland 2016 [Report on cancer events in Germany 2016]. Germany: Robert-Koch-Institut, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kalogirou C, Fender H, Muck P, et al. Long-term outcome of nephron-sparing surgery compared to radical nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma ⩾4 cm – a matched-pair single institution analysis. Urol Int 2017; 98: 138–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Prinsloo S, Wei Q, Scott SM, et al. Psychological states, serum markers and survival: associations and predictors of survival in patients with renal cell carcinoma. J Behav Med 2015; 38: 48–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boychuk SI, Dedkov AG, Volkov IB, et al. The patients quality of life estimation in presence of metastasis of renal cell cancer in the bones on background of the bisphosphonates application. Klin Khir 2016. April (4): 58–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Klaassen Z, Jen RP, DiBianco JM, et al. Factors associated with suicide in patients with genitourinary malignancies. Cancer 2015; 121: 1864–1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Strittmacher G, Mawick R, Tilkorn M. Entwicklung und klinischer Einsatz von Screeninginstrumenten zur Identifikation betreuungsbedürftigen Tumorpatienten [Development and clinical use of screening instruments for the identification of tumor patients in need of care]. In: Bullinger M, Siegrist J, Ravens-Sieberer U. (Hrsg) Lebensqualitätsforschung aus medizinpsychologischer und –soziologischer Perspektive. Jahrbuch der Medizinischen Psychologie 18 [Quality of life research from a medical-psychological and -sociological perspective. Yearbook of medical psychology 18]. Göttingen: Hogrefe, 2000, pp.59–75. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mehnert A, Lehmann C, Cao P, et al. Assessment of psychosocial distress and resources in oncology–a literature review about screening measures and current developments. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol 2006; 56: 462–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ralla B, Magheli A, Wolff I, et al. Prevalence of late-onset hypogonadism in men with localized and metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Urol Int 2017; 98: 191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ralla B, Erber B, Goranova I, et al. Retrospective analysis of fifth-line targeted therapy efficacy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Urol Int 2017; 98: 184–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol 2011; 12: 160–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Singer S, Das-Munshi J, Brähler E. Prevalence of mental health conditions in cancer patients in acute care – a meta-analysis. Psychooncology 2010; 19(Suppl.): 134–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vehling S, Koch U, Ladehoff N, et al. Prävalenz affektiver und Angststörungen bei Krebs: Systematischer Literaturreview und Metaanalyse [Prevalence of affective and anxiety disorders in cancer: systematic review of literature and meta-analysis]. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol 2012; 62: 249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Beisland E, Aarstad HJ, Aarstad AK, et al. Development of a disease-specific health-related quality of life (HRQoL) questionnaire intended to be used in conjunction with the general European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ) in renal cell carcinoma patients. Acta Oncol 2016; 55: 349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Larbig W, Tschuschke V. Psychologische Interventionseffekte bei Krebs – eine Einführung [Psychological intervention effects on cancer – an introduction]. In: Larbig W, Tschuschke V. (Hrsg) Psychologische Interventionen. Therapeutisches Vorgehen und Ergebnisse [Psycho-oncological interventions: therapeutic approach and results]. München: Reinhardt, 2000, pp.12–20. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Menzel R. Ein wesentlicher Beitrag zur Professionalisierung: psychosoziale Diagnosen in der onkologischen Sozialarbeit [An essential contribution to professionalization. Psychosocial diagnoses in oncological social work]. Forum Sozialarbeit und Gesundheit 2006. DSVG(2); 31–33. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Spiegel D, Kato PM. Psychosoziale Einflüsse auf Inzidenz und Progression von Krebs [Psychosocial influences on incidence and progression of cancer]. In: Larbig W, Tschuschke V. (Hrsg) Psychoonkologische Interventionen. Therapeutisches Vorgehen und Ergebnisse [Psycho-oncological interventions: therapeutic approach and results]. München: Reinhardt, 2000, pp.111–150. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bultz BD, Johansen C. Screening for distress, the 6th vital sign: where are we, and where are we going? Psychooncology 2011; 20: 569–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bultz BD, Groff SL, Fitch M, et al. Implementing screening for distress, the 6th vital sign: a Canadian strategy for changing practice. Psychooncology 2011; 20: 463–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Potash M, Breitbart W. Affective disorders in advanced cancer. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2002; 16: 671–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Given B, Given CW. Cancer treatment in older adults: implications for psychosocial research. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009; 57(Suppl. 2): S282–S285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mehnert A, Brähler E, Faller H, et al. Four-week prevalence of mental disorders in patients with cancer across major tumor entities. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32: 3540–3546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rose JH, Radziewicz R, Bowmans KF, et al. A coping and communication support intervention tailored to older patients diagnosed with late-stage cancer. Clin Interv Aging 2008; 3: 77–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Absolom K, Holch P, Pini S, et al. The detection and management of emotional distress in cancer patients: the views of health-care professionals. Psychooncology 2011; 20: 601–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kennard BD, Smith SM, Olvera R, et al. Nonadherence in adolescent oncology patients: preliminary data on psychological risk factors and relationships to outcome. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2004; 11: 30–39. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Von Essen I, Larsson G, Oberg K, et al. ‘Satisfaction with care’: associations with health-related quality of life and psychosocial function among Swedish patients with endocrine gastrointestinal tumours. Eur J Cancer Care 2002; 11: 91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bui QUT, Ostir GV, Kuo YF, et al. Relationship of depression to patient satisfaction: findings from the barriers to breast cancer study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2005; 89: 23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Prieto JM, Blanch J, Atala J, et al. Psychiatric morbidity and impact on hospital length of stay among hematologic cancer patients receiving stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol 2002; 20: 1907–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC, Given CW, et al. Relationship of caregiver reactions and depression to cancer patients’ symptoms, functional states and depression – a longitudinal view. Soc Sci Med 1995; 40: 837–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pelletier G, Verhoef MJ, Khatri N, et al. Quality of life in brain tumor patients: the relative contributions of depression, fatigue, emotional distress, and existential issues. J Neurooncol 2002; 57: 41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Valdimarsdóttir U, Helgason AR, Fürst CJ, et al. The unrecognised cost of cancer patients’ unrelieved symptoms: a nationwide follow-up of their surviving partners. Br J Cancer 2002; 86: 1540–1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Skarstein J, Aass N, Fosså SD, et al. Anxiety and depression in cancer patients: relation between the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire. J Psychosom Res 2000; 49: 27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hjerl K, Andersen EW, Keiding N, et al. Depression as a prognostic factor for breast cancer mortality. Psychosomatics 2003; 44: 24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Loberiza FR, Jr, Rizzo JD, Bredeson CN, et al. Association of depressive syndrome and early deaths among patients after stem-cell transplantation for malignant diseases. J Clin Oncol 2002; 20: 2118–2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Steel JL, Geller DA, Gamblin TC, et al. Depression, immunity, and survival in patients with hepatobiliary carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25: 2397–2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Passik SD, Dugan W, McDonald MV, et al. Oncologists’ recognition of depression in their patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16: 1594–1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fallowfield L, Ratcliffe D, Jenkins V, et al. Psychiatric morbidity and its recognition by doctors in patients with cancer. Br J Cancer 2001; 84: 1011–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sharpe M, Strong V, Allen K, et al. Major depression in outpatients attending a regional cancer centre: screening and unmet treatment needs. Br J Cancer 2004; 90: 314–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kruijver IP, Garssen B, Visser AP, et al. Signalising psychosocial problems in cancer care: the structural use of a short psychosocial checklist during medical or nursing visits. Patient Educ Couns 2006; 62: 163–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Velikova G, Booth L, Smith AB, et al. Measuring quality of life in routine oncology practice improves communication and patient well-being: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 714–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hilarius DL, Kloeg PH, Gundy CM, et al. Use of health-related quality-of-life assessments in daily clinical oncology nursing practice: a community hospital-based intervention study. Cancer 2008; 113: 628–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Detmar SB, Aaronson NK, Wever LD, et al. How are you feeling? Who wants to know? Patients’ and oncologists’ preferences for discussing health-related quality-of-life issues. J Clin Oncol 2000; 18: 3295–3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Taenzer P, Bultz BD, Carlson LE, et al. Impact of computerized quality of life screening on physician behaviour and patient satisfaction in lung cancer outpatients. Psychooncology 2000; 9: 203–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Carlson LE, Waller A, Mitchell AJ. Screening for distress and unmet needs in patients with cancer: review and recommendations. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30: 1160–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol 2011; 12: 160–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Faller H, Weis J, Koch U, et al. Utilization of professional psychological care in a large German sample of cancer patients. Psychooncology. Epub ahead of print 13 July 2016. DOI: 10.1002/pon.4197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Alon S. Psychosocial challenges of elderly patients coping with cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2011; 33(Suppl. 2): S122–S114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]