Abstract

Reprogramming of lipid metabolism is a newly recognized hallmark of malignancy. Increased lipid uptake, storage and lipogenesis occur in a variety of cancers and contribute to rapid tumor growth. Lipids constitute the basic structure of membranes and also function as signaling molecules and energy sources. Sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs), a family of membrane-bound transcription factors in the endoplasmic reticulum, play a central role in the regulation of lipid metabolism. Recent studies have revealed that SREBPs are highly up-regulated in various cancers and promote tumor growth. SREBP cleavage-activating protein is a key transporter in the trafficking and activation of SREBPs as well as a critical glucose sensor, thus linking glucose metabolism and de novo lipid synthesis. Targeting altered lipid metabolic pathways has become a promising anti-cancer strategy. This review summarizes recent progress in our understanding of lipid metabolism regulation in malignancy, and highlights potential molecular targets and their inhibitors for cancer treatment.

Keywords: Lipid metabolism, Cancer, SCAP, SREBPs, Fatty acids, Cholesterol, Lipid droplets

Background

Lipids, also known as fats, comprise thousands of different types of molecules, including phospholipids, fatty acids, triglycerides, sphingolipids, cholesterol, and cholesteryl esters. Lipids are widely distributed in cellular organelles and are critical components of all membranes [1–6]. In addition to their role as structural components, lipids in membranes also serve important functions of different organelles. Lipids could function as second messengers to transduce signals within cells, and serve as important energy sources when nutrients are limited [7–10]. Dysregulation of lipid metabolism contributes to the progression of various metabolic diseases, including cardiovascular diseases, obesity, hepatic steatosis, and diabetes [11–16].

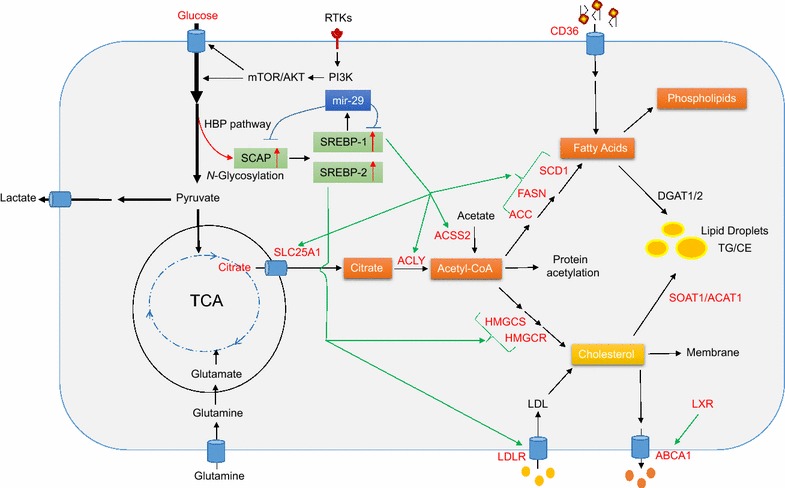

Mammalian cells acquire lipids through two mechanisms, i.e., de novo synthesis and uptake. Accumulating evidence has demonstrated that lipid metabolism is substantially reprogrammed in cancers [17–22]. Lipogenesis is strongly up-regulated in human cancers to satisfy the demands of increased membrane biogenesis [7, 8, 21, 23]. Lipid uptake and storage are also elevated in malignant tumors [24–33]. Sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs) are key transcription factors that regulate the expression of genes involved in lipid synthesis and uptake, and play a central role in lipid metabolism under both physiological and pathological conditions (Fig. 1). Dysregulation of SREBPs occurs in various metabolic syndromes and cancers [34–46]. Targeting the pathways regulating lipid metabolism has become a novel anti-cancer strategy. In this review, we summarize the recent progress in lipid metabolic regulation in malignancies, and discuss molecular targets for novel cancer therapy.

Fig. 1.

Regulation of lipid metabolism in cancer cells. In cancer cells, glucose uptake and glycolysis are markedly up-regulated by RTKs via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway, generating large amounts of pyruvate. Pyruvate is converted to lactate and it also enters the mitochondria, where it forms citrate, which is transported by SLC25A1 from the mitochondria into the cytoplasm, where the citrate serves as a precursor for de novo synthesis of fatty acids and cholesterol. Glutamine can also enter into mitochondria and participate in energy production and lipid synthesis. Acetate is converted to acetyl-CoA by the ACSS2 enzyme, serving as another source of lipid synthesis. Glucose participates in the HBP to form glycans that will be added to proteins during glycosylation. Oncogenic EGFR signaling increases N-glycosylation of SCAP, which activates SREBP-1 and -2 [55, 58], which ultimately up-regulate expression of enzymes in lipogenesis pathways and expression of LDLR. The enzyme up-regulation promotes fatty acid and cholesterol synthesis, while the LDLR up-regulation increases cholesterol uptake [40]. The microRNA miRNA-29 regulates the SCAP/SREBP pathway via a novel negative feedback loop [101]. The transporter CD36 brings fatty acids into cancer cells. When cellular fatty acids and cholesterol are in excess, they can be converted to TG and CE by the enzymes DGAT1/2 and SOAT1/ACAT1, forming LDs. When present in excess, cholesterol can be converted to 22- or 27-hydroxycholesterol, which activate LXR to up-regulate ABCA1 expression, promoting cholesterol efflux. ABCA1 ATP-binding cassette transporters A, ACC acetyl-CoA carboxylase, ACLY ATP citrate lyase, ACSS2 acetyl-CoA synthetase 2, DGAT1/2 diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 1/2, FAs fatty acids, FASN fatty acid synthase, HBP hexosamine biosynthesis pathway, HMGCR 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase, HMGCS 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase, LD lipid droplet, LDLR low-density lipoprotein receptor, LXR liver X receptor, RTKs oncogenic tyrosine kinase receptors, SCAP SREBP cleavage-activating protein, SCD1 stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1, SLC25A1 solute carrier family 25 member 1, SOAT1 (also known as ACAT1) sterol O-acyltransferase, SREBPs sterol regulatory element-binding proteins, TG/CE triglycerides/cholesteryl esters

Nutrient sources for lipid synthesis

Glucose is the major substrate for de novo lipid synthesis (Fig. 1). It is converted to pyruvate through glycolysis, and enters mitochondria to form citrate, which is then released into the cytoplasm to serve as a precursor for the synthesis of both fatty acids and cholesterol [47, 48]. Multiple glucose transporters as well as a series of enzymes that regulate glycolysis and lipid synthesis are strongly up-regulated in cancer cells [20, 21, 28, 49–54]. Glucose also participates in the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway to generate essential metabolites for the glycosylation of numerous proteins and lipids [55–57]. In this way, glycosylation is linked to the regulation of lipid metabolism [55, 58].

Glutamine could also be used for energy production and lipid synthesis via the tricarboxylic acid cycle in mitochondria [59–62]. Glutamine is the most abundant amino acid in the blood and tissues [63, 64]. It is a major nitrogen donor essential for tumor growth. Glutamine transporters, such as SLC1A5 (also known as ASCT2), are up-regulated in various cancers [65, 66]. After entering cells, glutamine can be converted to glutamate and α-ketoglutarate in the mitochondria, and generate ATP through oxidative phosphorylation [59–61, 67, 68]. Under conditions of hypoxia or defective mitochondria, glutamine-derived α-ketoglutarate is converted to citrate through reductive carboxylation and thereby contributes to de novo lipid synthesis [34, 69–71]. Acetate can also serve as a substrate for lipid synthesis after it is converted to acetyl-CoA in the cytoplasm [72–74].

De novo lipid synthesis

Key regulators of lipogenesis—SREBPs, acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), fatty acid synthase (FASN), and stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1) [27, 75–81]—are significantly up-regulated in various human cancers [20, 21, 28, 49–51]. Below we detail the roles of these proteins and discuss their potential as molecular targets in cancer treatment.

SCAP/SREBPs

SREBPs are a family of basic-helix-loop-helix leucine zipper transcription factors that regulate de novo synthesis of fatty acids and cholesterol as well as cholesterol uptake [11, 12, 82]. Mammalian cells express three SREBP proteins, SREBP-1a, -1c and -2, which are encoded by two genes, SREBF1 and SREBF2. SREBF1 encodes SREBP-1a and -1c proteins via alternative transcriptional start sites. The SREBP-1a protein is ~ 24 amino acids longer than -1c at its NH2-terminus, and has stronger transcriptional activity. SREBP-1a regulates fatty acid and cholesterol synthesis as well as cholesterol uptake, whereas SREBP-1c mainly controls fatty acid synthesis [83–86]. SREBF2 encodes the SREBP-2 protein, and plays a major role in the regulation of cholesterol synthesis and uptake [87–92].

SREBPs are synthesized as inactive precursors that interact with SREBP cleavage-activating protein (SCAP), a polytopic transmembrane protein that binds to the insulin-induced gene protein (Insig), which is anchored to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). The resulting Insig/SCAP/SREBP complex is retained in the ER [93–95]. Dissociation of SCAP from Insig, followed by a conformational change in SCAP, activates SREBP transcriptional activity. Conformational change in SCAP exposes a specific motif that allows SCAP to bind to Sec23/24 proteins, generating COPII-mediated translocation vesicles. SCAP mediates the entry of SREBPs into COPII vesicles that transport the SCAP/SREBP complex from the ER to the Golgi. In the Golgi, site 1 and 2 proteases (S1P and S2P) sequentially cleave SREBPs to release their N-terminal domains, which enter the nucleus and activate the transcription of genes involved in lipid synthesis and uptake (Fig. 1) [11, 12, 87, 88, 95, 96]. This process is negatively regulated by ER sterols, which are able to bind to SCAP or Insig and enhance their association, leading to the retention of SCAP/SREBP in the ER and reduction of SREBP activation [97–100]. Our research group recently showed that microRNA-29 (miR-29) participates in the negative feedback control of the SCAP/SREBP signaling pathway. We found that SREBP-1 up-regulates miR-29 transcription, and the microRNA binds to the 3′-untranslated region of SCAP and SREBP-1 transcripts and inhibit their translation [101, 102].

SCAP N-glycosylation

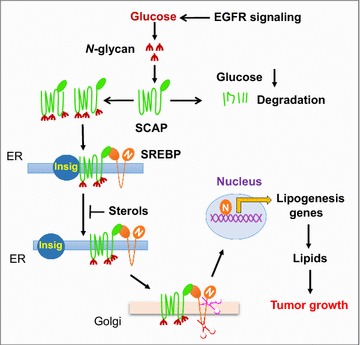

A recent series of studies in our laboratory showed that glucose could activate SCAP/SREBP trafficking and activation (Fig. 2) [55, 103, 104]. We tested the effects of glucose intermediate metabolites on different metabolic pathways, including glycolysis, oxidative phosphorylation, and hexosamine synthesis for glycosylation. We found that only N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), an intermediate in the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway, activates SREBPs when glucose supply is limited. We found that inhibiting N-glycosylation, but not O-glycosylation, abolished glucose-mediated SCAP up-regulation and SREBP activation, indicating that glucose-mediated N-glycosylation of SCAP is essential for SCAP/SREBP trafficking and activation. These findings also demonstrated a coordinated molecular regulation mechanism that links glucose availability and the rate of de novo lipid synthesis (Fig. 2) [55, 58, 105].

Fig. 2.

SCAP N-glycosylation is essential for SREBP trafficking and activation. SREBP activation is repressed by the ER-resident protein Insig, which binds to SCAP to prevent SREBP translocation and nuclear activation. The Nobel Prize-winning laboratories of Brown and Goldstein revealed that sterols modulate Insig interaction with SCAP to retain the SCAP/SREBP complex in the ER and inhibit SREBP [273, 274]. Our recent work has shown that glucose-mediated N-glycosylation stabilizes SCAP and promotes its dissociation from Insig, triggering the trafficking of the SCAP/SREBP complex from the ER to the Golgi, where SREBPs are cleaved to release their transcriptionally active N-terminal fragments to activate lipogenesis for tumor growth [55]. We further showed that EGFR signaling enhances glucose intake and thereby promotes SCAP N-glycosylation and SREBP activation

SREBP activation in malignancy

The importance of SREBPs in cancer has begun to be recognized. Our group discovered that SREBP-1 is markedly up-regulated in glioblastoma [34, 106–108], the most common primary brain tumor and one of the most lethal cancers [34, 109–113]. Glioblastomas depend strongly on lipogenesis for rapid growth when they express the amplified tyrosine kinase receptor called epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) or its constitutively active mutant form EGFRvIII. This mutant lacks a portion of the extracellular ligand-binding domain [34, 106, 108, 111, 114, 115]. EGFR/EGFRvIII promotes lipid synthesis by activating SREBP-1 via PI3K/Akt signaling [12, 34, 87]. The nuclei of human glioblastoma cells display elevated levels of SREBP-1 [34], suggesting that the SCAP/SREBP complex may escape the tight repression of Insig, leading to high SREBP activation. Other groups have found elevated SREBP-1 in various cancers, and SREBP-1 levels in various cell lines are regulated by PI3K/Akt signaling and mTORC1 [116–122]. How SREBP-1 is activated in cancer cells is not entirely understood and requires further investigation.

Inhibiting SREBPs at the genetic level or with pharmacological agents significantly suppresses tumor growth and induces cancer cell death, making SREBPs promising therapeutic targets [28, 34, 123–137]. However, directly inhibiting SREBPs is challenging, as transcription factors often make poor drug targets. A more promising approach is to inhibit SREBP translocation from the ER to the Golgi. Along this line, fatostatin, betulin and PF-429242 have been shown to inhibit SREBP activation and have promising anti-tumor effects in pre-clinical studies [126–131].

SREBP-2 is up-regulated in prostate cancer [37, 138]. SREBP-2 regulates 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA) reductase, the rate-limiting enzyme for cholesterol synthesis. Inhibiting SREBP-2 has been explored as an anti-cancer therapy [139–144]. Statins are inhibitors of HMG-CoA reductase and are widely used to reduce circulating cholesterol levels. The anti-cancer effects of statins have been tested for various types of cancers, both pre-clinically and in patients [140, 142, 143, 145]. However, inhibition of cholesterol synthesis can lead to feedback activation of SREBPs, making the anti-cancer effects of statins less effective [144]. Thus, combination therapies that simultaneously inhibit cholesterol synthesis and SREBP activation are being developed [146, 147].

SLC25A1

A critical step for glucose-mediated de novo lipid synthesis is the release of citrate from mitochondria into the cytoplasm. Solute carrier family 25 member 1 (SLC25A1), also referred to as citrate carrier (CIC), functions as a key transporter to export citrate from mitochondria to the cytoplasm, providing a key precursor for both fatty acid and cholesterol synthesis [148, 149] (Fig. 1). SLC25A1 is regulated by SREBP-1 [150] and plays an important role in inflammation and tumor growth [151, 152]. In lung cancer cells, SLC25A1 is up-regulated by mutant p53 [151]. These findings, though preliminary, suggest that specific inhibitors of SLC25A1 may have anti-tumor effects.

ACLY

ATP citrate lyase (ACLY) converts cytoplasmic citrate to acetyl-CoA, a precursor of lipid synthesis (Fig. 1) [153–155] and a substrate for protein acetylation [153]. ACLY is a downstream target of SREBPs [156–158], and is up-regulated in many cancers, including glioblastoma, colorectal cancer, breast cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma [159–161]. Inhibiting ACLY at the genetic level or pharmacologically significantly suppresses tumor growth [162–164]. The ACLY inhibitor SB-204990 strongly inhibits tumor growth in mice with lung, prostate or ovarian cancer xenografts [162, 165]. These results suggest that ACLY may serve as an attractive anti-cancer target [155].

ACSS2

Acetate is converted to acetyl-CoA by acetyl-CoA synthetases (ACSSs), making acetate an important molecule for lipid synthesis and histone acetylation [7]. In mammalian cells, ACSS isoforms 1 and 3 localize to the mitochondria, whereas isoform 2 is found in the cytoplasm and nucleus [166]. Isoform 2 expression is regulated by SREBPs [167]. When each isoform was genetically knocked down in HepG2 cells, only ACSS2 down-regulation dramatically suppressed acetate-mediated lipid synthesis and histone modification [72]. In fact, ACSS2 expression correlates inversely with overall survival in patients with triple-negative breast cancer, liver cancer, glioma or lung cancer [72, 73, 168, 169]. Studies with patient-derived glioblastoma xenografts have shown that acetate contributes to acetyl-CoA synthesis in tumors [73]. Indeed, cancer cells rely mainly on acetate as a carbon source for fatty acid synthesis under hypoxic conditions [74]. Knocking down ACSS2 suppresses proliferation of several cancer cell lines as well as growth of xenograft tumors [74, 170–173]. ACSS2 also participates in autophagy when glucose supply is limited: it triggers histone acetylation in the promoter regions of autophagy genes, enhancing their expression [174, 175].

ACCs

Following the conversion of citrate and acetate to acetyl-CoA, the ACC enzymes catalyze ATP-dependent carboxylation of acetyl-CoA, generating malonyl-CoA for fatty acid synthesis (Fig. 1). Two ACC isoforms have been identified in mammalian cells, ACC-alpha (also termed ACC1) and ACC-beta (also known as ACC2) [176, 177]. ACC is up-regulated in several human cancers, including glioblastoma and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [34, 178]. Inhibiting ACCs significantly reduces fatty acid synthesis and suppresses tumor growth in various xenograft models [179–186]. The ACC inhibitors TOFA, soraphen A and ND646 have shown significant anti-tumor effects in xenograft tumor models (Table 1) [179–184].

Table 1.

Representative targets within the lipid metabolism pathway for anti-cancer drug development

| Target protein | Inhibitor | Type of cancer | Preclinical model | Clinical trial | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCAP | – | GBM | Xenografts | – | [55] |

| SREBPs | Fatostatin, betulin, PF-429242, xanthohumol | GBM, prostate, liver, skin, melanoma, colorectal, bile duct, pancreatic, and breast cancer | Xenografts | – | [28, 125–138] |

| ACCs | TOFA, soraphen A, ND-646 | Lung, ovarian cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | Xenografts | – | [179–185] |

| ACLY | SB-204990, bempedoic acid, BMS303141 | Lung, prostate, and ovarian cancer | Xenografts | – | [152, 162, 165] |

| FASN | Cerulenin | Ovarian cancer, breast cancer | Xenografts | – | [179, 194–196] |

| C75 | Breast, GBM, renal, and mesothelioma cancer | Xenografts | – | [34, 179, 188, 197–203] | |

| TVB-2640 | Solid malignant tumors | – | Phase I | Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02223247), [191] | |

| TVB-3166 | Lung, ovary, and pancreatic cancer | Xenografts | – | [264] | |

| C93 | Ovarian and lung cancer | Xenografts | – | [265, 266] | |

| C247 | Breast cancer | – | [267] | ||

| Orlistat | Prostate cancer and melanoma | Xenografts | – | [192, 193] | |

| Triclosan | Breast cancer | Xenografts | – | [268, 269] | |

| LDLR | – | GBM | – | – | [27, 219] |

| SCD1 | BZ36, A939572, MF-438 | Prostate, renal cancer | Xenografts | – | [124, 212–215, 270] |

| LXR | GW3965, LXR-623 | GBM | Xenografts | – | [27, 238, 239] |

| SR9243 | Prostate cancer | Xenografts | [242] | ||

| SOAT1 (or ACAT1) | K604, ATR-101, avasimibe | GBM, prostate and pancreatic cancer | Xenografts | – | [28, 230–232] |

| CPT1 | Etomoxir, perhexiline | Leukemia, prostate and breast cancer | Xenografts, transgenic mice | – | [248–250, 271, 272] |

| CD36 | Anti-CD36 antibodies | Oral cancer | Xenografts | – | [24–26] |

ACCs acetyl-CoA carboxylases, ACLY ATP citrate lyase, CD36 cluster of differentiation 36, also known as fatty acid translocase (FAT), CPT1 carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1, FASN fatty acid synthase, GBM glioblastoma multiforme, LDLR low-density lipoprotein receptor, LXR liver X receptor, SCAP SREBP cleavage-activating protein, SREBPs sterol regulatory element-binding proteins

FASN

Fatty acid synthase (FASN), a key lipogenic enzyme catalyzing the last step in de novo biogenesis of fatty acids, has been studied extensively in various cancers [21, 187–191]. The early-generation FASN inhibitors C75, cerulenin and orlistat (Table 1) have been studied pre-clinically, but their pharmacology and side effects limited their potential for clinical use [34, 179, 188–203]. The later-generation inhibitor TVB-2640 has entered clinical trials in patients with solid tumors (Table 1) [21, 191, 204, 205].

SCD1

Stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD) is an ER-resident integral membrane protein that catalyzes the formation of the mono-unsaturated fatty acids oleic acid (18:1) or palmitoleic acid (16:1) from stearoyl-(18:0) or palmitoyl-CoA (16:0) [206, 207]. There are 5 SCD genes (SCD1-5). Humans contain the SCD homologs SCD1 and SCD5, but the function of SCD5 remains unknown [208–210]. The mono-unsaturated products of SCD1 are key substrates in the formation of membrane phospholipids, cholesteryl esters and triglycerides, making SCD1 a promising anti-cancer target [75, 211]. The SCD1 inhibitors BZ36, A939572 and MF-438 have shown anti-tumor effects in pre-clinical xenograft models (Table 1) [212–215].

Lipid uptake

CD36

In addition to de novo synthesis, lipid uptake from the exogenous environment is another important route through which cells acquire fatty acids. CD36 transports fatty acids into the cell [216, 217], and plays a critical role in cancer cell growth, metastasis and the epithelial-mesenchymal transition [24–26]. An anti-CD36 antibody has shown significant anti-metastatic efficacy in oral cancer xenograft models [25].

LDLR

Cholesterol is an essential structural component of cell membranes [2, 218]. Cholesterol could be synthesized by cells de novo or through internalizing low-density lipoprotein (LDL). LDL binds to the membrane-bound LDL receptor (LDLR) and is internalized, after which it enters lysosomes, where free cholesterol is released [11, 76]. LDLR is up-regulated in glioblastoma via EGFR/PI3K/Akt/SREBP-1 signaling [27], and plays an important role in tumor growth [27, 76, 219]. LDLR has not been investigated as an anti-cancer target.

Lipid storage/lipid droplets

SOAT1/ACAT1

When cellular lipids are in excess, they are converted to triglycerides and cholesteryl esters in the ER, forming lipid droplets [220–222]. These droplets have been observed in various types of tumor, including glioblastoma, renal clear cell carcinoma, and cancers of the prostate, colon or pancreas [29–33]. Diglyceride acyltransferase 1/2 (DGAT1/2) could synthesize triglyceride from diacylglycerol and acyl-CoA (Fig. 1) [223, 224]. So far, the role of triglycerides in cancer cells has not been explored.

Cholesteryl esters are abundant in tumor tissue, while they are usually undetectable in normal tissue [225–229]. Sterol O-acyltransferase 1 (SOAT1), also known as acyl-CoA acyltransferase 1 (ACAT1), converts cholesterol to cholesteryl esters for storage in lipid droplets (Fig. 1). This enzyme is highly expressed in glioblastomas and in cancer of the prostate or pancreas; its expression level correlates inversely with patient survival [28, 29, 230–235]. Genetically silencing SOAT1/ACAT1 or blocking its activity using the inhibitors K604, ATR-101 or avasimibe effectively suppresses tumor growth in several cancer xenograft models [28, 230–232]. These results suggest that targeting SOAT1 and cholesteryl ester synthesis may be a promising anti-cancer strategy.

Cholesterol efflux

LXR/ABCA1

Cholesterol homeostasis is critical for maintaining cellular function, and is regulated by de novo synthesis, uptake, storage, and efflux [11, 76]. Increases in cholesterol levels can trigger feedback inhibition of cholesterol biosynthesis or conversion of cholesterol into cholesteryl esters stored in lipid droplets. Levels of 22- or 27-hydroxycholesterol can also increase, and these molecules bind to and activate the liver X receptor, which turns on expression of ATP-binding cassette proteins A1 (ABCA1) and G1 (ABCG1) [236]. Both proteins are plasma membrane-bound transporters that promote cholesterol export and thereby reduce intracellular cholesterol levels [237]. Synthetic liver X receptor agonists GW3965 and T0901317 significantly inhibit tumor growth in animal models of glioblastoma, breast cancer or prostate cancer [7, 27]. Activation of the liver X receptor by GW3965 up-regulates a ubiquitin ligase E3 that degrades LDLR [27, 62, 238]. The highly brain-penetrant liver X receptor agonist LXR-623 selectively kills glioblastoma cells and prolongs survival of glioblastoma-bearing mice [239]. Therefore, the combination of increasing cholesterol efflux by activating the liver X receptor and decreasing cholesterol uptake may be a promising anti-cancer strategy.

Activation of liver X receptor up-regulates transcription of glycolysis genes, such as those encoding PFK2 and GCK1, as well as of lipogenesis genes, such as those encoding SREBP-1c, FASN, and SCD [240, 241]. Conversely, inhibiting the liver X receptor using the inverse agonist SR9243 downregulates expression of PFK2 and SREBP-1c, thereby inhibiting glycolysis and fatty acid synthesis as well as suppressing xenograft tumor growth [242]. These results suggest that developing antagonists against liver X receptors may be a new anti-cancer direction. However, such an approach can be effective only if the liver X receptor shows high transcriptional activity in human tumors, which has not been clearly demonstrated yet. Moreover, inhibiting liver X receptors alone may be insufficient for reducing glycolysis and lipogenesis in human tumors, since these metabolic programs are up-regulated by multiple oncogenic signaling pathways [243–245]. Regardless, efforts to inhibit cancer growth by using liver X receptor agonists to activate cholesterol efflux can be undermined by the concomitant up-regulation of glycolysis and lipogenesis. It may be more effective to simultaneously enhance cholesterol efflux and inhibit glycolysis and lipogenesis.

Fatty acid oxidation

CPT1

Fatty acids are an important energy source for cell growth and survival when nutrients are limiting. Carnitine palmitoyltransferase I (CPT1) converts fatty acids to acylcarnitines, which are shuttled into mitochondria, where they undergo β-oxidation and produce energy [21]. Fatty acid β-oxidation plays a critical role in tumor growth [246, 247], and the CPT1 inhibitors etomoxir and perhexiline have been tested for anti-cancer effects in various animal models [248–250].

Lipid peroxidation and cell death

Lipids, particularly polyunsaturated fatty acids, are susceptible to oxidation by oxygen free radicals, leading to lipid peroxidation that is harmful to cells and tissues [251–253]. Lipid peroxides are associated with many pathological states, including inflammation, neurodegenerative disease, cancer, and ocular and kidney degeneration [253, 254]. Lipid peroxidation triggers the propagation of lipid reactive oxygen species that can significantly alter the physical properties of cellular membranes, or degrade into reactive compounds that cross-link DNA or proteins, exerting further toxic effects [253, 255, 256]. Extensive lipid peroxidation can result in ferroptosis, a regulated form of iron-dependent, non-apoptotic cell death [255, 257]. Inducing ferroptosis may be an anti-cancer strategy [257–259]. For example, disrupting the repair of oxidative damage to bio-membranes by inhibiting the antioxidant enzyme glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) could induce ferroptosis [257, 259–262]. This has emerged as an active area of research that may lead to new anti-cancer approaches, particularly against metabolically active tumors.

Summary

Extensive studies have provided strong evidence for reprogramming of lipid metabolism in cancer [27, 34, 55]. A variety of lipid synthesis inhibitors have shown promising anti-cancer effects in preclinical studies and early phases of clinical trials [7, 29, 55, 263]. However, major barriers exists in developing cancer treatment by targeting altered lipid metabolism, mostly due to incomplete understanding of the mechanisms that regulate lipid synthesis, storage, utilization and efflux in cancer cells.

Authors’ contributions

CC performed the literature search and drafted the manuscript. FG and XC assisted in the literature search and helped draft sections of the manuscript. DG designed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr. Martine Torres for critical review of the manuscript and editorial assistance.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and Table 1.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH Grant NS079701 (DG), American Cancer Society Research Scholar Grant RSG-14-228-01-CSM (DG), OSUCCC Idea Grant (DG), an OSUCCC Translational Therapeutic Program seed grant (DG), a Pelotonia Postdoc Fellowship (CC) and an OSU Department of Radiation-Oncology Basic Research seed Grant (CC).

Contributor Information

Chunming Cheng, Email: Chunming.cheng@osumc.edu.

Feng Geng, Email: Feng.geng@osumc.edu.

Xiang Cheng, Email: Xiang.cheng@osumc.edu.

Deliang Guo, Phone: 614-366-3774, Email: deliang.guo@osumc.edu.

References

- 1.Maxfield FR. Plasma membrane microdomains. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14(4):483–487. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(02)00351-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mukherjee S, Maxfield FR. Membrane domains. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:839–866. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.095451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pomorski T, Hrafnsdottir S, Devaux PF, van Meer G. Lipid distribution and transport across cellular membranes. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2001;12(2):139–148. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2000.0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Meer G. Membranes in motion. EMBO Rep. 2010;11(5):331–333. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Meer G, Voelker DR, Feigenson GW. Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(2):112–124. doi: 10.1038/nrm2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holthuis JC, Menon AK. Lipid landscapes and pipelines in membrane homeostasis. Nature. 2014;510(7503):48–57. doi: 10.1038/nature13474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo D, Bell EH, Chakravarti A. Lipid metabolism emerges as a promising target for malignant glioma therapy. CNS Oncol. 2013;2(3):289–299. doi: 10.2217/cns.13.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menendez JA, Lupu R. Fatty acid synthase and the lipogenic phenotype in cancer pathogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(10):763–777. doi: 10.1038/nrc2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zechner R, Strauss JG, Haemmerle G, Lass A, Zimmermann R. Lipolysis: pathway under construction. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2005;16(3):333–340. doi: 10.1097/01.mol.0000169354.20395.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Efeyan A, Comb WC, Sabatini DM. Nutrient-sensing mechanisms and pathways. Nature. 2015;517(7534):302–310. doi: 10.1038/nature14190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstein JL, Brown MS. A century of cholesterol and coronaries: from plaques to genes to statins. Cell. 2015;161(1):161–172. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldstein JL, DeBose-Boyd RA, Brown MS. Protein sensors for membrane sterols. Cell. 2006;124(1):35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwartz MW, Seeley RJ, Tschop MH, Woods SC, Morton GJ, Myers MG, et al. Cooperation between brain and islet in glucose homeostasis and diabetes. Nature. 2013;503(7474):59–66. doi: 10.1038/nature12709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosen ED, Spiegelman BM. What we talk about when we talk about fat. Cell. 2014;156(1–2):20–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perry RJ, Samuel VT, Petersen KF, Shulman GI. The role of hepatic lipids in hepatic insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2014;510(7503):84–91. doi: 10.1038/nature13478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen JC, Horton JD, Hobbs HH. Human fatty liver disease: old questions and new insights. Science. 2011;332(6037):1519–1523. doi: 10.1126/science.1204265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abramson HN. The lipogenesis pathway as a cancer target. J Med Chem. 2011;54(16):5615–5638. doi: 10.1021/jm2005805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grossi-Paoletti E, Paoletti P, Fumagalli R. Lipids in brain tumors. J Neurosurg. 1971;34(3):454–455. doi: 10.3171/jns.1971.34.3.0454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Podo F. Tumour phospholipid metabolism. NMR Biomed. 1999;12(7):413–439. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1492(199911)12:7<413::AID-NBM587>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santos CR, Schulze A. Lipid metabolism in cancer. FEBS J. 2012;279(15):2610–2623. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rohrig F, Schulze A. The multifaceted roles of fatty acid synthesis in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16(11):732–749. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schulze A, Harris AL. How cancer metabolism is tuned for proliferation and vulnerable to disruption. Nature. 2012;491(7424):364–373. doi: 10.1038/nature11706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoon S, Lee MY, Park SW, Moon JS, Koh YK, Ahn YH, et al. Up-regulation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase alpha and fatty acid synthase by human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 at the translational level in breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(36):26122–26131. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao J, Zhi Z, Wang C, Xing H, Song G, Yu X, et al. Exogenous lipids promote the growth of breast cancer cells via CD36. Oncol Rep. 2017;38(4):2105–2115. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pascual G, Avgustinova A, Mejetta S, Martin M, Castellanos A, Attolini CS, et al. Targeting metastasis-initiating cells through the fatty acid receptor CD36. Nature. 2017;541(7635):41–45. doi: 10.1038/nature20791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nath A, Li I, Roberts LR, Chan C. Elevated free fatty acid uptake via CD36 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14752. doi: 10.1038/srep14752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo D, Reinitz F, Youssef M, Hong C, Nathanson D, Akhavan D, et al. An LXR agonist promotes glioblastoma cell death through inhibition of an EGFR/AKT/SREBP-1/LDLR-dependent pathway. Cancer Discov. 2011;1(5):442–456. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geng F, Cheng X, Wu X, Yoo JY, Cheng C, Guo JY, et al. Inhibition of SOAT1 suppresses glioblastoma growth via blocking SREBP-1-mediated lipogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(21):5337–5348. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geng F, Guo D. Lipid droplets, potential biomarker and metabolic target in glioblastoma. Intern Med Rev (Washington, DC) 2017 doi: 10.18103/imr.v3i5.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koizume S, Miyagi Y. Lipid Droplets: a key cellular organelle associated with cancer cell survival under normoxia and hypoxia. Int J Mol Sci. 2016 doi: 10.3390/ijms17091430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yue S, Li J, Lee SY, Lee HJ, Shao T, Song B, et al. Cholesteryl ester accumulation induced by PTEN loss and PI3 K/AKT activation underlies human prostate cancer aggressiveness. Cell Metab. 2014;19(3):393–406. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Accioly MT, Pacheco P, Maya-Monteiro CM, Carrossini N, Robbs BK, Oliveira SS, et al. Lipid bodies are reservoirs of cyclooxygenase-2 and sites of prostaglandin-E2 synthesis in colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68(6):1732–1740. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gaida MM, Mayer C, Dapunt U, Stegmaier S, Schirmacher P, Wabnitz GH, et al. Expression of the bitter receptor T2R38 in pancreatic cancer: localization in lipid droplets and activation by a bacteria-derived quorum-sensing molecule. Oncotarget. 2016;7(11):12623–12632. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo D, Prins RM, Dang J, Kuga D, Iwanami A, Soto H, et al. EGFR signaling through an Akt-SREBP-1-dependent, rapamycin-resistant pathway sensitizes glioblastomas to antilipogenic therapy. Sci Signal. 2009;2(101):ra82. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeon TI, Osborne TF. SREBPs: metabolic integrators in physiology and metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2012;23(2):65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shao W, Espenshade PJ. Expanding roles for SREBP in metabolism. Cell Metab. 2012;16(4):414–419. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ettinger SL, Sobel R, Whitmore TG, Akbari M, Bradley DR, Gleave ME, et al. Dysregulation of sterol response element-binding proteins and downstream effectors in prostate cancer during progression to androgen independence. Cancer Res. 2004;64(6):2212–2221. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-2148-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang Y, Morin PJ, Han WF, Chen T, Bornman DM, Gabrielson EW, et al. Regulation of fatty acid synthase expression in breast cancer by sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c. Exp Cell Res. 2003;282(2):132–137. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4827(02)00023-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bao J, Zhu L, Zhu Q, Su J, Liu M, Huang W. SREBP-1 is an independent prognostic marker and promotes invasion and migration in breast cancer. Oncol Lett. 2016;12(4):2409–2416. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang WC, Li X, Liu J, Lin J, Chung LW. Activation of androgen receptor, lipogenesis, and oxidative stress converged by SREBP-1 is responsible for regulating growth and progression of prostate cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2012;10(1):133–142. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-11-0206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yin F, Sharen G, Yuan F, Peng Y, Chen R, Zhou X, et al. TIP30 regulates lipid metabolism in hepatocellular carcinoma by regulating SREBP1 through the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Oncogenesis. 2017;6(6):e347. doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2017.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun Y, He W, Luo M, Zhou Y, Chang G, Ren W, et al. SREBP1 regulates tumorigenesis and prognosis of pancreatic cancer through targeting lipid metabolism. Tumour Biol. 2015;36(6):4133–4141. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li C, Yang W, Zhang J, Zheng X, Yao Y, Tu K, et al. SREBP-1 has a prognostic role and contributes to invasion and metastasis in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15(5):7124–7138. doi: 10.3390/ijms15057124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walker AK, Jacobs RL, Watts JL, Rottiers V, Jiang K, Finnegan DM, et al. A conserved SREBP-1/phosphatidylcholine feedback circuit regulates lipogenesis in metazoans. Cell. 2011;147(4):840–852. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Soyal SM, Nofziger C, Dossena S, Paulmichl M, Patsch W. Targeting SREBPs for treatment of the metabolic syndrome. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2015;36(6):406–416. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muller-Wieland D, Knebel B, Haas J, Kotzka J. SREBP-1 and fatty liver. Clinical relevance for diabetes, obesity, dyslipidemia and atherosclerosis. Herz. 2012;37(3):273–278. doi: 10.1007/s00059-012-3608-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luengo A, Gui DY, Vander Heiden MG. Targeting metabolism for cancer therapy. Cell Chem Biol. 2017;24(9):1161–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Min HY, Lee HY. Oncogene-driven metabolic alterations in cancer. Biomol Ther (Seoul) 2017 doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2017.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gopal K, Grossi E, Paoletti P, Usardi M. Lipid composition of human intracranial tumors: a biochemical study. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1963;11:333–347. doi: 10.1007/BF01402012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Currie E, Schulze A, Zechner R, Walther TC, Farese RV., Jr Cellular fatty acid metabolism and cancer. Cell Metab. 2013;18(2):153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shimano H, Sato R. SREBP-regulated lipid metabolism: convergent physiology—divergent pathophysiology. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017 doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schlosser HA, Drebber U, Urbanski A, Haase S, Baltin C, Berlth F, et al. Glucose transporters 1, 3, 6, and 10 are expressed in gastric cancer and glucose transporter 3 is associated with UICC stage and survival. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20(1):83–91. doi: 10.1007/s10120-015-0577-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sharen G, Peng Y, Cheng H, Liu Y, Shi Y, Zhao J. Prognostic value of GLUT-1 expression in pancreatic cancer: results from 538 patients. Oncotarget. 2017;8(12):19760–19767. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun HW, Yu XJ, Wu WC, Chen J, Shi M, Zheng L, et al. GLUT1 and ASCT2 as predictors for prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(12):e0168907. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cheng C, Ru P, Geng F, Liu J, Yoo JY, Wu X, et al. Glucose-mediated N-glycosylation of SCAP is essential for SREBP-1 activation and tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2015;28(5):569–581. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ryczko MC, Pawling J, Chen R, Abdel Rahman AM, Yau K, Copeland JK, et al. Metabolic reprogramming by hexosamine biosynthetic and golgi N-glycan branching pathways. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23043. doi: 10.1038/srep23043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Adeva-Andany MM, Perez-Felpete N, Fernandez-Fernandez C, Donapetry-Garcia C, Pazos-Garcia C. Liver glucose metabolism in humans. Biosci Rep. 2016 doi: 10.1042/BSR20160385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guo D. SCAP links glucose to lipid metabolism in cancer cells. Mol Cell Oncol. 2016 doi: 10.1080/23723556.2015.1132120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dang CV, Le A, Gao P. MYC-induced cancer cell energy metabolism and therapeutic opportunities. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(21):6479–6483. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barger JF, Plas DR. Balancing biosynthesis and bioenergetics: metabolic programs in oncogenesis. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17(4):R287–R304. doi: 10.1677/ERC-10-0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dang CV. Therapeutic targeting of Myc-reprogrammed cancer cell metabolism. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2011;76:369–374. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2011.76.011296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.DeBerardinis RJ, Mancuso A, Daikhin E, Nissim I, Yudkoff M, Wehrli S, et al. Beyond aerobic glycolysis: transformed cells can engage in glutamine metabolism that exceeds the requirement for protein and nucleotide synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(49):19345–19350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709747104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bergstrom J, Furst P, Noree LO, Vinnars E. Intracellular free amino acid concentration in human muscle tissue. J Appl Physiol. 1974;36(6):693–697. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1974.36.6.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wishart DS, Jewison T, Guo AC, Wilson M, Knox C, Liu Y, et al. HMDB 3.0–the human metabolome database in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue):D801–D807. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.DeBerardinis RJ, Cheng T. Q’s next: the diverse functions of glutamine in metabolism, cell biology and cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29(3):313–324. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bhutia YD, Babu E, Ramachandran S, Ganapathy V. Amino Acid transporters in cancer and their relevance to “glutamine addiction”: novel targets for the design of a new class of anticancer drugs. Cancer Res. 2015;75(9):1782–1788. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Erickson JW, Cerione RA. Glutaminase: a hot spot for regulation of cancer cell metabolism? Oncotarget. 2010;1(8):734–740. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wise DR, Ward PS, Shay JE, Cross JR, Gruber JJ, Sachdeva UM, et al. Hypoxia promotes isocitrate dehydrogenase-dependent carboxylation of alpha-ketoglutarate to citrate to support cell growth and viability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(49):19611–19616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117773108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Metallo CM, Gameiro PA, Bell EL, Mattaini KR, Yang J, Hiller K, et al. Reductive glutamine metabolism by IDH1 mediates lipogenesis under hypoxia. Nature. 2012;481(7381):380–384. doi: 10.1038/nature10602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mullen AR, Wheaton WW, Jin ES, Chen PH, Sullivan LB, Cheng T, et al. Reductive carboxylation supports growth in tumour cells with defective mitochondria. Nature. 2012;481(7381):385–388. doi: 10.1038/nature10642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Le A, Lane AN, Hamaker M, Bose S, Gouw A, Barbi J, et al. Glucose-independent glutamine metabolism via TCA cycling for proliferation and survival in B cells. Cell Metab. 2012;15(1):110–121. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Comerford SA, Huang Z, Du X, Wang Y, Cai L, Witkiewicz AK, et al. Acetate dependence of tumors. Cell. 2014;159(7):1591–1602. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mashimo T, Pichumani K, Vemireddy V, Hatanpaa KJ, Singh DK, Sirasanagandla S, et al. Acetate is a bioenergetic substrate for human glioblastoma and brain metastases. Cell. 2014;159(7):1603–1614. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schug ZT, Peck B, Jones DT, Zhang Q, Grosskurth S, Alam IS, et al. Acetyl-CoA synthetase 2 promotes acetate utilization and maintains cancer cell growth under metabolic stress. Cancer Cell. 2015;27(1):57–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Peck B, Schulze A. Lipid desaturation - the next step in targeting lipogenesis in cancer? FEBS J. 2016;283(15):2767–2778. doi: 10.1111/febs.13681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Goldstein JL, Brown MS. The LDL receptor. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29(4):431–438. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.179564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Di Vizio D, Adam RM, Kim J, Kim R, Sotgia F, Williams T, et al. Caveolin-1 interacts with a lipid raft-associated population of fatty acid synthase. Cell Cycle. 2008;7(14):2257–2267. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.14.6475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cai Y, Wang J, Zhang L, Wu D, Yu D, Tian X, et al. Expressions of fatty acid synthase and HER2 are correlated with poor prognosis of ovarian cancer. Med Oncol. 2015;32(1):391. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0391-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Long QQ, Yi YX, Qiu J, Xu CJ, Huang PL. Fatty acid synthase (FASN) levels in serum of colorectal cancer patients: correlation with clinical outcomes. Tumour Biol. 2014;35(4):3855–3859. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-1510-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Witkiewicz AK, Nguyen KH, Dasgupta A, Kennedy EP, Yeo CJ, Lisanti MP, et al. Co-expression of fatty acid synthase and caveolin-1 in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: implications for tumor progression and clinical outcome. Cell Cycle. 2008;7(19):3021–3025. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.19.6719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Walter K, Hong SM, Nyhan S, Canto M, Fedarko N, Klein A, et al. Serum fatty acid synthase as a marker of pancreatic neoplasia. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(9):2380–2385. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nohturfft A, Zhang SC. Coordination of lipid metabolism in membrane biogenesis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2009;25:539–566. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shimano H, Horton JD, Shimomura I, Hammer RE, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Isoform 1c of sterol regulatory element binding protein is less active than isoform 1a in livers of transgenic mice and in cultured cells. J Clin Invest. 1997;99(5):846–854. doi: 10.1172/JCI119248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shimomura I, Shimano H, Horton JD, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Differential expression of exons 1a and 1c in mRNAs for sterol regulatory element binding protein-1 in human and mouse organs and cultured cells. J Clin Invest. 1997;99(5):838–845. doi: 10.1172/JCI119247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang X, Sato R, Brown MS, Hua X, Goldstein JL. SREBP-1, a membrane-bound transcription factor released by sterol-regulated proteolysis. Cell. 1994;77(1):53–62. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90234-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yokoyama C, Wang X, Briggs MR, Admon A, Wu J, Hua X, et al. SREBP-1, a basic-helix-loop-helix-leucine zipper protein that controls transcription of the low density lipoprotein receptor gene. Cell. 1993;75(1):187–197. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(05)80095-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Horton JD, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. SREBPs: activators of the complete program of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis in the liver. J Clin Invest. 2002;109(9):1125–1131. doi: 10.1172/JCI0215593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Horton JD, Shah NA, Warrington JA, Anderson NN, Park SW, Brown MS, et al. Combined analysis of oligonucleotide microarray data from transgenic and knockout mice identifies direct SREBP target genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(21):12027–12032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1534923100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Horton JD, Shimomura I, Ikemoto S, Bashmakov Y, Hammer RE. Overexpression of sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1a in mouse adipose tissue produces adipocyte hypertrophy, increased fatty acid secretion, and fatty liver. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(38):36652–36660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306540200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hua X, Wu J, Goldstein JL, Brown MS, Hobbs HH. Structure of the human gene encoding sterol regulatory element binding protein-1 (SREBF1) and localization of SREBF1 and SREBF2 to chromosomes 17p11.2 and 22q13. Genomics. 1995;25(3):667–673. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(95)80009-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hua X, Yokoyama C, Wu J, Briggs MR, Brown MS, Goldstein JL, et al. SREBP-2, a second basic-helix-loop-helix-leucine zipper protein that stimulates transcription by binding to a sterol regulatory element. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90(24):11603–11607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shimano H, Shimomura I, Hammer RE, Herz J, Goldstein JL, Brown MS, et al. Elevated levels of SREBP-2 and cholesterol synthesis in livers of mice homozygous for a targeted disruption of the SREBP-1 gene. J Clin Invest. 1997;100(8):2115–2124. doi: 10.1172/JCI119746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lee PC, Sever N, Debose-Boyd RA. Isolation of sterol-resistant Chinese hamster ovary cells with genetic deficiencies in both Insig-1 and Insig-2. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(26):25242–25249. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502989200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sun LP, Li L, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Insig required for sterol-mediated inhibition of Scap/SREBP binding to COPII proteins in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(28):26483–26490. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504041200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sun LP, Seemann J, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Sterol-regulated transport of SREBPs from endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi: Insig renders sorting signal in Scap inaccessible to COPII proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(16):6519–6526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700907104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nohturfft A, Yabe D, Goldstein JL, Brown MS, Espenshade PJ. Regulated step in cholesterol feedback localized to budding of SCAP from ER membranes. Cell. 2000;102(3):315–323. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Espenshade PJ, Li WP, Yabe D. Sterols block binding of COPII proteins to SCAP, thereby controlling SCAP sorting in ER. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(18):11694–11699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182412799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yang T, Espenshade PJ, Wright ME, Yabe D, Gong Y, Aebersold R, et al. Crucial step in cholesterol homeostasis: sterols promote binding of SCAP to INSIG-1, a membrane protein that facilitates retention of SREBPs in ER. Cell. 2002;110(4):489–500. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00872-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Adams CM, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Cholesterol-induced conformational change in SCAP enhanced by Insig proteins and mimicked by cationic amphiphiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(19):10647–10652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1534833100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Adams CM, Reitz J, De Brabander JK, Feramisco JD, Li L, Brown MS, et al. Cholesterol and 25-hydroxycholesterol inhibit activation of SREBPs by different mechanisms, both involving SCAP and Insigs. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(50):52772–52780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410302200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ru P, Hu P, Geng F, Mo X, Cheng C, Yoo JY, et al. Feedback loop regulation of SCAP/SREBP-1 by miR-29 modulates EGFR signaling-driven glioblastoma growth. Cell Rep. 2016;16(6):1527–1535. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ru P, Guo D. microRNA-29 mediates a novel negative feedback loop to regulate SCAP/SREBP-1 and lipid metabolism. RNA Dis. 2017 doi: 10.14800/rd.1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Guo D. SCAP links glucose to lipid metabolism in cancer cells. Mol Cell Oncol. 2016 doi: 10.1080/23723556.2015.1132120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shao W, Espenshade PJ. Sugar makes fat by talking to SCAP. Cancer Cell. 2015;28(5):548–549. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cheng C, Guo JY, Geng F, Wu X, Cheng X, Li Q, et al. Analysis of SCAP N-glycosylation and trafficking in human cells. J Vis Exp. 2016 doi: 10.3791/54709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Guo D, Hildebrandt IJ, Prins RM, Soto H, Mazzotta MM, Dang J, et al. The AMPK agonist AICAR inhibits the growth of EGFRvIII-expressing glioblastomas by inhibiting lipogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(31):12932–12937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906606106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ru P, Williams TM, Chakravarti A, Guo D. Tumor metabolism of malignant gliomas. Cancers (Basel) 2013;5(4):1469–1484. doi: 10.3390/cancers5041469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Guo D, Bell EH, Mischel P, Chakravarti A. Targeting SREBP-1-driven lipid metabolism to treat cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20(15):2619–2626. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wen PY, Kesari S. Malignant gliomas in adults. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(5):492–507. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0708126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Taphoorn MJ, Janzer RC, et al. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(5):459–466. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Furnari FB, Fenton T, Bachoo RM, Mukasa A, Stommel JM, Stegh A, et al. Malignant astrocytic glioma: genetics, biology, and paths to treatment. Genes Dev. 2007;21(21):2683–2710. doi: 10.1101/gad.1596707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Paleologos NA, Merrell RT. Anaplastic glioma. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2012;14(4):381–390. doi: 10.1007/s11940-012-0177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ricard D, Idbaih A, Ducray F, Lahutte M, Hoang-Xuan K, Delattre JY. Primary brain tumours in adults. Lancet. 2012;379(9830):1984–1996. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Huang HS, Nagane M, Klingbeil CK, Lin H, Nishikawa R, Ji XD, et al. The enhanced tumorigenic activity of a mutant epidermal growth factor receptor common in human cancers is mediated by threshold levels of constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation and unattenuated signaling. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(5):2927–2935. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.5.2927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Yoshimoto K, Dang J, Zhu S, Nathanson D, Huang T, Dumont R, et al. Development of a real-time RT-PCR assay for detecting EGFRvIII in glioblastoma samples. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(2):488–493. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Du X, Kristiana I, Wong J, Brown AJ. Involvement of Akt in ER-to-Golgi transport of SCAP/SREBP: a link between a key cell proliferative pathway and membrane synthesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17(6):2735–2745. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e05-11-1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Porstmann T, Griffiths B, Chung YL, Delpuech O, Griffiths JR, Downward J, et al. PKB/Akt induces transcription of enzymes involved in cholesterol and fatty acid biosynthesis via activation of SREBP. Oncogene. 2005;24(43):6465–6481. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Porstmann T, Santos CR, Griffiths B, Cully M, Wu M, Leevers S, et al. SREBP activity is regulated by mTORC1 and contributes to Akt-dependent cell growth. Cell Metab. 2008;8(3):224–236. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Duvel K, Yecies JL, Menon S, Raman P, Lipovsky AI, Souza AL, et al. Activation of a metabolic gene regulatory network downstream of mTOR complex 1. Mol Cell. 2010;39(2):171–183. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Yecies JL, Zhang HH, Menon S, Liu S, Yecies D, Lipovsky AI, et al. Akt stimulates hepatic SREBP1c and lipogenesis through parallel mTORC1-dependent and independent pathways. Cell Metab. 2011;14(1):21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Peterson TR, Sengupta SS, Harris TE, Carmack AE, Kang SA, Balderas E, et al. mTOR complex 1 regulates lipin 1 localization to control the SREBP pathway. Cell. 2011;146(3):408–420. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ricoult SJ, Yecies JL, Ben-Sahra I, Manning BD. Oncogenic PI3K and K-Ras stimulate de novo lipid synthesis through mTORC1 and SREBP. Oncogene. 2015 doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Williams KJ, Argus JP, Zhu Y, Wilks MQ, Marbois BN, York AG, et al. An essential requirement for the SCAP/SREBP signaling axis to protect cancer cells from lipotoxicity. Cancer Res. 2013;73(9):2850–2862. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0382-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.von Roemeling CA, Marlow LA, Wei JJ, Cooper SJ, Caulfield TR, Wu K, et al. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 is a novel molecular therapeutic target for clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(9):2368–2380. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Li N, Zhou ZS, Shen Y, Xu J, Miao HH, Xiong Y, et al. Inhibition of the sterol regulatory element-binding protein pathway suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma by repressing inflammation in mice. Hepatology. 2017;65(6):1936–1947. doi: 10.1002/hep.29018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kamisuki S, Mao Q, Abu-Elheiga L, Gu Z, Kugimiya A, Kwon Y, et al. A small molecule that blocks fat synthesis by inhibiting the activation of SREBP. Chem Biol. 2009;16(8):882–892. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Li X, Chen YT, Hu P, Huang WC. Fatostatin displays high antitumor activity in prostate cancer by blocking SREBP-regulated metabolic pathways and androgen receptor signaling. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13(4):855–866. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Li X, Wu JB, Chung LW, Huang WC. Anti-cancer efficacy of SREBP inhibitor, alone or in combination with docetaxel, in prostate cancer harboring p53 mutations. Oncotarget. 2015;6(38):41018–41032. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Krol SK, Kielbus M, Rivero-Muller A, Stepulak A. Comprehensive review on betulin as a potent anticancer agent. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:584189. doi: 10.1155/2015/584189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Gholkar AA, Cheung K, Williams KJ, Lo YC, Hamideh SA, Nnebe C, et al. Fatostatin inhibits cancer cell proliferation by affecting mitotic microtubule spindle assembly and cell division. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(33):17001–17008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C116.737346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Shao W, Machamer CE, Espenshade PJ. Fatostatin blocks ER exit of SCAP but inhibits cell growth in a SCAP-independent manner. J Lipid Res. 2016;57(8):1564–1573. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M069583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Miyata S, Inoue J, Shimizu M, Sato R. Xanthohumol improves diet-induced obesity and fatty liver by suppressing sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP) activation. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(33):20565–20579. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.656975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Soica C, Dehelean C, Danciu C, Wang HM, Wenz G, Ambrus R, et al. Betulin complex in gamma-cyclodextrin derivatives: properties and antineoplasic activities in in vitro and in vivo tumor models. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(11):14992–15011. doi: 10.3390/ijms131114992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Shikata Y, Yoshimaru T, Komatsu M, Katoh H, Sato R, Kanagaki S, et al. Protein kinase A inhibition facilitates the antitumor activity of xanthohumol, a valosin-containing protein inhibitor. Cancer Sci. 2017;108(4):785–794. doi: 10.1111/cas.13175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Dokduang H, Yongvanit P, Namwat N, Pairojkul C, Sangkhamanon S, Yageta MS, et al. Xanthohumol inhibits STAT3 activation pathway leading to growth suppression and apoptosis induction in human cholangiocarcinoma cells. Oncol Rep. 2016;35(4):2065–2072. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.4584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Jiang W, Zhao S, Xu L, Lu Y, Lu Z, Chen C, et al. The inhibitory effects of xanthohumol, a prenylated chalcone derived from hops, on cell growth and tumorigenesis in human pancreatic cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2015;73:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2015.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Monteiro R, Calhau C, Silva AO, Pinheiro-Silva S, Guerreiro S, Gartner F, et al. Xanthohumol inhibits inflammatory factor production and angiogenesis in breast cancer xenografts. J Cell Biochem. 2008;104(5):1699–1707. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Li X, Wu JB, Li Q, Shigemura K, Chung LW, Huang WC. SREBP-2 promotes stem cell-like properties and metastasis by transcriptional activation of c-Myc in prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(11):12869–12884. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Vallianou NG, Kostantinou A, Kougias M, Kazazis C. Statins and cancer. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2014;14(5):706–712. doi: 10.2174/1871520613666131129105035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Osmak M. Statins and cancer: current and future prospects. Cancer Lett. 2012;324(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Zhang J, Yang Z, Xie L, Xu L, Xu D, Liu X. Statins, autophagy and cancer metastasis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45(3):745–752. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Bathaie SZ, Ashrafi M, Azizian M, Tamanoi F. Mevalonate pathway and human cancers. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2017;10(2):77–85. doi: 10.2174/1874467209666160112123205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Nayan M, Punjani N, Juurlink DN, Finelli A, Austin PC, Kulkarni GS, et al. Statin use and kidney cancer survival outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;52:105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Pandyra AA, Mullen PJ, Goard CA, Ericson E, Sharma P, Kalkat M, et al. Genome-wide RNAi analysis reveals that simultaneous inhibition of specific mevalonate pathway genes potentiates tumor cell death. Oncotarget. 2015;6(29):26909–26921. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Nayan M, Finelli A, Jewett MA, Juurlink DN, Austin PC, Kulkarni GS, et al. Statin use and kidney cancer outcomes a propensity score analysis. Urol Oncol. 2016;34(11):487-e1–487-e6. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Pandyra A, Penn LZ. Targeting tumor cell metabolism via the mevalonate pathway: two hits are better than one. Mol Cell Oncol. 2014;1(4):e969133. doi: 10.4161/23723548.2014.969133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Pandyra A, Mullen PJ, Kalkat M, Yu R, Pong JT, Li Z, et al. Immediate utility of two approved agents to target both the metabolic mevalonate pathway and its restorative feedback loop. Cancer Res. 2014;74(17):4772–4782. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Catalina-Rodriguez O, Kolukula VK, Tomita Y, Preet A, Palmieri F, Wellstein A, et al. The mitochondrial citrate transporter, CIC, is essential for mitochondrial homeostasis. Oncotarget. 2012;3(10):1220–1235. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Convertini P, Menga A, Andria G, Scala I, Santarsiero A, Castiglione Morelli MA, et al. The contribution of the citrate pathway to oxidative stress in Down syndrome. Immunology. 2016;149(4):423–431. doi: 10.1111/imm.12659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Infantino V, Iacobazzi V, De Santis F, Mastrapasqua M, Palmieri F. Transcription of the mitochondrial citrate carrier gene: role of SREBP-1, upregulation by insulin and downregulation by PUFA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;356(1):249–254. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.02.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Kolukula VK, Sahu G, Wellstein A, Rodriguez OC, Preet A, Iacobazzi V, et al. SLC25A1, or CIC, is a novel transcriptional target of mutant p53 and a negative tumor prognostic marker. Oncotarget. 2014;5(5):1212–1225. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Assmann N, O’Brien KL, Donnelly RP, Dyck L, Zaiatz-Bittencourt V, Loftus RM, et al. Srebp-controlled glucose metabolism is essential for NK cell functional responses. Nat Immunol. 2017;18(11):1197–1206. doi: 10.1038/ni.3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Zhao S, Torres A, Henry RA, Trefely S, Wallace M, Lee JV, et al. ATP-citrate lyase controls a glucose-to-acetate metabolic switch. Cell Rep. 2016;17(4):1037–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.09.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.He Y, Gao M, Cao Y, Tang H, Liu S, Tao Y. Nuclear localization of metabolic enzymes in immunity and metastasis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2017;1868(2):359–371. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Zaidi N, Swinnen JV, Smans K. ATP-citrate lyase: a key player in cancer metabolism. Cancer Res. 2012;72(15):3709–3714. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-4112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Moon YA, Lee JJ, Park SW, Ahn YH, Kim KS. The roles of sterol regulatory element-binding proteins in the transactivation of the rat ATP citrate-lyase promoter. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(39):30280–30286. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001066200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Sato R, Okamoto A, Inoue J, Miyamoto W, Sakai Y, Emoto N, et al. Transcriptional regulation of the ATP citrate-lyase gene by sterol regulatory element-binding proteins. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(17):12497–12502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.17.12497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Amemiya-Kudo M, Shimano H, Hasty AH, Yahagi N, Yoshikawa T, Matsuzaka T, et al. Transcriptional activities of nuclear SREBP-1a, -1c, and -2 to different target promoters of lipogenic and cholesterogenic genes. J Lipid Res. 2002;43(8):1220–1235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Khwairakpam AD, Shyamananda MS, Sailo BL, Rathnakaram SR, Padmavathi G, Kotoky J, et al. ATP citrate lyase (ACLY): a promising target for cancer prevention and treatment. Curr Drug Targets. 2015;16(2):156–163. doi: 10.2174/1389450115666141224125117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Osugi J, Yamaura T, Muto S, Okabe N, Matsumura Y, Hoshino M, et al. Prognostic impact of the combination of glucose transporter 1 and ATP citrate lyase in node-negative patients with non-small lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2015;88(3):310–318. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Csanadi A, Kayser C, Donauer M, Gumpp V, Aumann K, Rawluk J, et al. Prognostic value of malic enzyme and ATP-citrate lyase in non-small cell lung cancer of the young and the elderly. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(5):e0126357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Hatzivassiliou G, Zhao F, Bauer DE, Andreadis C, Shaw AN, Dhanak D, et al. ATP citrate lyase inhibition can suppress tumor cell growth. Cancer Cell. 2005;8(4):311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Lee JH, Jang H, Lee SM, Lee JE, Choi J, Kim TW, et al. ATP-citrate lyase regulates cellular senescence via an AMPK- and p53-dependent pathway. FEBS J. 2015;282(2):361–371. doi: 10.1111/febs.13139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Hanai JI, Doro N, Seth P, Sukhatme VP. ATP citrate lyase knockdown impacts cancer stem cells in vitro. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e696. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Bauer DE, Hatzivassiliou G, Zhao F, Andreadis C, Thompson CB. ATP citrate lyase is an important component of cell growth and transformation. Oncogene. 2005;24(41):6314–6322. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Watkins PA, Maiguel D, Jia Z, Pevsner J. Evidence for 26 distinct acyl-coenzyme A synthetase genes in the human genome. J Lipid Res. 2007;48(12):2736–2750. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700378-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Xu H, Luo J, Ma G, Zhang X, Yao D, Li M, et al. Acyl-CoA synthetase short-chain family member 2 (ACSS2) is regulated by SREBP-1 and plays a role in fatty acid synthesis in caprine mammary epithelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(2):1005–1016. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Sun L, Kong Y, Cao M, Zhou H, Li H, Cui Y, et al. Decreased expression of acetyl-CoA synthase 2 promotes metastasis and predicts poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2017;108(7):1338–1346. doi: 10.1111/cas.13252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Gao X, Lin SH, Ren F, Li JT, Chen JJ, Yao CB, et al. Acetate functions as an epigenetic metabolite to promote lipid synthesis under hypoxia. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11960. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Yu T, Cui L, Liu C, Wang G, Wu T, Huang Y. Expression of acetyl coenzyme A synthetase 2 in colorectal cancer and its biological role. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2017;20(10):1174–1179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Lakhter AJ, Hamilton J, Konger RL, Brustovetsky N, Broxmeyer HE, Naidu SR. Glucose-independent acetate metabolism promotes melanoma cell survival and tumor growth. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(42):21869–21879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.712166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Yun M, Bang SH, Kim JW, Park JY, Kim KS, Lee JD. The importance of acetyl coenzyme A synthetase for 11C-acetate uptake and cell survival in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(8):1222–1228. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.062703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Yoshii Y, Waki A, Furukawa T, Kiyono Y, Mori T, Yoshii H, et al. Tumor uptake of radiolabeled acetate reflects the expression of cytosolic acetyl-CoA synthetase: implications for the mechanism of acetate PET. Nucl Med Biol. 2009;36(7):771–777. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Li X, Yu W, Qian X, Xia Y, Zheng Y, Lee JH, et al. Nucleus-translocated ACSS2 promotes gene transcription for lysosomal biogenesis and autophagy. Mol Cell. 2017;66(5):684–697. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Li X, Qian X, Lu Z. Local histone acetylation by ACSS2 promotes gene transcription for lysosomal biogenesis and autophagy. Autophagy. 2017;13(10):1790–1791. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2017.1349581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Wang C, Rajput S, Watabe K, Liao DF, Cao D. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase-a as a novel target for cancer therapy. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2010;2:515–526. doi: 10.2741/s82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Zu X, Zhong J, Luo D, Tan J, Zhang Q, Wu Y, et al. Chemical genetics of acetyl-CoA carboxylases. Molecules. 2013;18(2):1704–1719. doi: 10.3390/molecules18021704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Su YW, Lin YH, Pai MH, Lo AC, Lee YC, Fang IC, et al. Association between phosphorylated AMP-activated protein kinase and acetyl-CoA carboxylase expression and outcome in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e96183. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Pizer ES, Thupari J, Han WF, Pinn ML, Chrest FJ, Frehywot GL, et al. Malonyl-coenzyme-A is a potential mediator of cytotoxicity induced by fatty-acid synthase inhibition in human breast cancer cells and xenografts. Cancer Res. 2000;60(2):213–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Guseva NV, Rokhlin OW, Glover RA, Cohen MB. TOFA (5-tetradecyl-oxy-2-furoic acid) reduces fatty acid synthesis, inhibits expression of AR, neuropilin-1 and Mcl-1 and kills prostate cancer cells independent of p53 status. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;12(1):80–85. doi: 10.4161/cbt.12.1.15721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Li S, Qiu L, Wu B, Shen H, Zhu J, Zhou L, et al. TOFA suppresses ovarian cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Mol Med Rep. 2013;8(2):373–378. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Tan W, Zhong Z, Wang S, Suo Z, Yang X, Hu X, et al. Berberine regulated lipid metabolism in the presence of C75, compound C, and TOFA in breast cancer cell line MCF-7. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2015;2015:396035. doi: 10.1155/2015/396035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183.Wang C, Xu C, Sun M, Luo D, Liao DF, Cao D. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase-alpha inhibitor TOFA induces human cancer cell apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;385(3):302–306. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184.Svensson RU, Parker SJ, Eichner LJ, Kolar MJ, Wallace M, Brun SN, et al. Inhibition of acetyl-CoA carboxylase suppresses fatty acid synthesis and tumor growth of non-small-cell lung cancer in preclinical models. Nat Med. 2016;22(10):1108–1119. doi: 10.1038/nm.4181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185.Luo J, Hong Y, Lu Y, Qiu S, Chaganty BK, Zhang L, et al. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase rewires cancer metabolism to allow cancer cells to survive inhibition of the Warburg effect by cetuximab. Cancer Lett. 2017;384:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186.Jones JE, Esler WP, Patel R, Lanba A, Vera NB, Pfefferkorn JA, et al. Inhibition of acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 (ACC1) and 2 (ACC2) reduces proliferation and de novo lipogenesis of EGFRvIII human glioblastoma cells. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(1):e0169566. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 187.Menendez JA, Lupu R. Fatty acid synthase (FASN) as a therapeutic target in breast cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2017 doi: 10.1080/14728222.2017.1381087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 188.Menendez JA, Vellon L, Mehmi I, Oza BP, Ropero S, Colomer R, et al. Inhibition of fatty acid synthase (FAS) suppresses HER2/neu (erbB-2) oncogene overexpression in cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(29):10715–10720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403390101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 189.Visca P, Sebastiani V, Botti C, Diodoro MG, Lasagni RP, Romagnoli F, et al. Fatty acid synthase (FAS) is a marker of increased risk of recurrence in lung carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2004;24(6):4169–4173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 190.Merino Salvador M, Gomez de Cedron M, Merino Rubio J, Falagan Martinez S, Sanchez Martinez R, Casado E, et al. Lipid metabolism and lung cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2017;112:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 191.Jones SF, Infante JR. Molecular pathways: fatty acid synthase. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(24):5434–5438. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 192.Kridel SJ, Axelrod F, Rozenkrantz N, Smith JW. Orlistat is a novel inhibitor of fatty acid synthase with antitumor activity. Cancer Res. 2004;64(6):2070–2075. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]