Abstract

Abortion stigma is influenced by a variety of factors. Previous research has documented a range of contributors to stigma, but the influence of perceived social norms about contraception has not been significantly investigated. This study assesses the influence of perceived social norms about contraception on abortion stigma among women in Luanda, Angola. This analysis uses data from the 2012 Angolan Community Family Planning Survey. Researchers employed multi-stage random sampling to collect demographic, social, and reproductive information from a representative sample of Luandan women aged 15–49. Researchers analyzed data from 1469 respondents using chi-square and multiple logistic regression. Researchers analyzed women’s perceptions of how their partners, friends, communities, and the media perceived contraception, and examined associations between those perceptions and respondents’ abortion stigma. Stigma was approximated by likelihood to help someone get an abortion, likelihood to help someone who needed medical attention after an abortion, and likelihood to avoid disclosing abortion experience. Higher levels of partner engagement in family planning discussion were associated with increased stigma on two of the three outcome measures, while higher levels of partner support of contraception were associated with decreased stigma. Perceived community acceptance of family planning and media discussion of family planning were associated with a decrease in likelihood to help someone receive an abortion. These results suggest that increasing partner support of family planning may be one strategy to help reduce abortion stigma. Results also suggest that some abortion stigma in Angola stems not from abortion itself, but rather from judgment about socially unacceptable pregnancies.

Keywords: Abortion, Stigma, Angola, Contraception use, Social-ecological model

Highlights

-

•

Review of data from 1469 Luandan women links perceived birth control attitudes and abortion stigma.

-

•

Perceived pro-contraception norms associated with unwillingness to help someone get an abortion.

-

•

Some abortion stigma may represent stigmatization of a socially unacceptable pregnancy.

-

•

Family planning programs may both counter abortion stigma and address contraceptive needs.

1. Introduction

Recent global estimates indicate that approximately 15% of total maternal mortality is attributed to abortion-related causes (Kassebaum et al., 2014), and abortion stigma, a shared understanding that abortion is morally wrong or socially unacceptable, is increasingly identified as a contributor to this mortality. Abortion stigma puts women’s mental and physical health at risk by silencing their ability to speak about their abortion experiences (Goyaux et al., 1999, Kimport et al., 2011). Stigma also reduces access to safe abortion, driving providers away from providing services and rendering abortion a clandestine service accessed through word of mouth, if at all (Bingham et al., 2011, Freedman et al., 2010). Deaths from abortion-related causes are most common in countries with highly restrictive abortion laws (Say et al., 2014, Singh et al., 2018).

1.1. Angola

Little is known about abortion in Angola. The country spent nearly three decades ravaged by a violent civil war, which, despite having officially ended in 2002, has had ongoing devastating effects on health record-keeping and health systems infrastructure (Bloemen, 2010). Moreover, abortion is largely illegal in Angola (Population Policy Data Bank, n.d.), with exceptions for saving the life of the pregnant person and pregnancies resulting from rape. The available abortion estimates are regional: an estimated 1 million abortions took place in Middle Africa between 2010 and 2014, equivalent to an abortion rate of approximately 35 abortions per 1000 women aged 15–44 years (Sedgh et al., 2016).

Imprisonment for performing an abortion in Angola can range from 2–8 years Angola’s abortion restrictions and started during colonization, originating in Portugal’s Criminal Code of 1886 (Ngwena, 2004). Though the colonial law itself was not based on moral or religious considerations (Brookman-Amissah & Moyo, 2004), Angola’s strict abortion penal code is reinforced by religious attitudes in the country, which are predominantly Christian and 41% Roman Catholic (Central Intelligence Agency, 2014, Population Policy Data Bank, n.d.). In 2009, Pope Benedict XVI inveighed against abortion in a speech to nearly a million Angolan Catholics, calling abortion a strain on the traditional African family (Simpson, 2009). Angolan bishops have expressed similar attitudes, fervently opposing efforts to shift abortion laws (Baklinski, 2012). Norris et al. (2011) argue that legal restrictions on abortion cause abortion stigma: encoding abortion in law as an illicit act can “reinforce the notion that abortion is morally wrong” (2011). Illegality, in turn, compromises the safety of abortion and creates the view that abortion is dirty or unhealthy.

In contrast to the stigmatization and opposition to abortion prevalent in many parts of Angola, recommendations from international human rights, women’s, and public health organizations have targeted mortality rates from unsafe abortion as a key priority for Angola. Angola’s criminalization of abortion has been identified as an area of concern hindering implementation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (Human Rights Committee, 2013). Angola has ratified the African Union’s Protocol to the Charter on People’s and Human Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa, which affirms women’s rights to control their fertility and advocates for abortion in several circumstances (Maiga, 2012). In recent years, non-government organizations (NGOs), in collaboration with the Ministry of Health, have implemented post-abortion care interventions to improve access to and management of cases of incomplete abortion and miscarriage, including the introduction of misoprostol to manage uncomplicated cases in peripheral health centers (Venture Strategies Innovations, 2013).

2. Theory

2.1. Conceptualizing abortion stigma

Many definitions and discussions of stigma build off Erving Goffman’s characterization of stigma as “an attribute that is deeply discrediting” which transforms a “whole and usual” person into a “tainted, discounted” one (Goffman, 1963). Abortion stigma presents an interesting case for this theory, as Kumar et al. discuss in their examination of the phenomenon (Kumar, Hessini, & Mitchell, 2009). Per Kumar et al., abortion experiences usually leave no “enduring stigmata” to differentiate those who have had abortions from those who have not, abortion can be a relatively invisible experience and many people can choose whether to publically identify as having had an abortion (Kumar et al., 2009). This under-reporting of abortion, as well as misclassification of abortion, creates the perception that abortion is rare and exceptional, hence establishing people who have abortions as deviant. This perceived deviance establishes people who have abortions as opposed to assumed norms of womanhood. Once those who have abortions are established as non-normative, they can be labeled and are connected to a range of negative stereotypes, leading to discrimination. This discrimination leads people to fear stigmatization for having abortions, leading to underreporting and creating what Kumar et al. term the “prevalence paradox”: though incidence of abortion is high, silencing of abortion experiences leads to the perception that abortion is rare, and therefore deviant (Kumar et al., 2009). This, in turn, leads to restriction of abortion access, social isolation, and negative health consequences for people who have abortions (Ellison, 2003, Major and Gramzow, 1999).

These various abortion stigma frameworks reinforce that though abortion stigma is a phenomenon with global health implications, it is fundamentally developed in a local social context. Norris et al. argue that people having abortions, their close peers, and abortion providers are the individuals primarily influenced by abortion stigma (Norris et al., 2011). When considering maternal health, however, it becomes clear that the health implications of abortion stigma extend beyond the individual level. Using a social-ecological framework for understanding abortion stigma helps clarify the ways in which individual beliefs create and are created by different social actors.

2.2. Social-ecological framework for abortion stigma

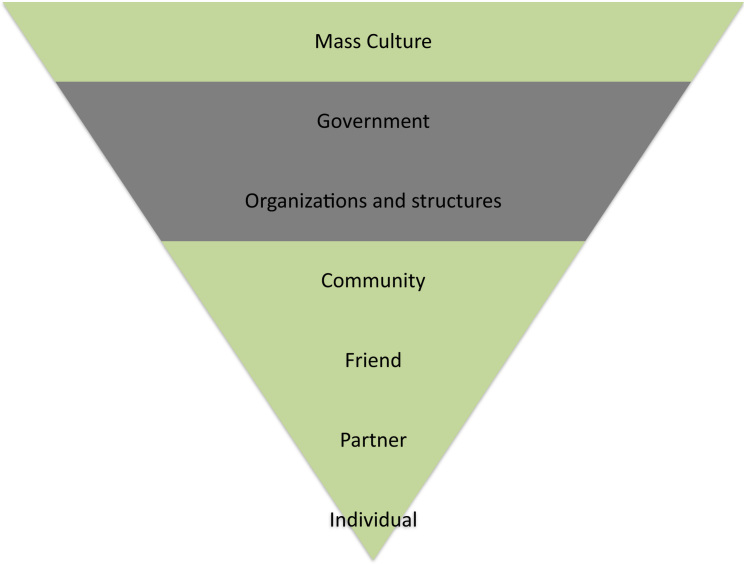

Social-ecological models situate health behaviors and beliefs within multiple levels of influence. Levels of influence are variously defined, but may include interpersonal relationships, organizations, and the policy environment (Sallis, Owen, & Fisher, 2015). In this article, we explore a few levels that may contribute to abortion stigma in Angola, based off the social-ecological model by Kumar et al. (2009) for understanding abortion stigma, which is in turn based off Heijinders and Van der Meij’s model for health stigma (Heijnders & Van Der Meij, 2006). Kumar et al. (2009) propose five levels of influence in their model: framing discourses and mass culture; government and structure; organization and institutions; community; and individual levels. In Angola, individual, community, and mass culture are avenues for addressing stigma which are currently less-developed: government interventions, in the form of Angolan abortion law reforms, are already in process; the recent legalization of abortion in cases of rape and maternal health may help address elements of abortion stigma caused by abortion’s illegal status. Similarly, organizational interventions, in the form of changes to healthcare systems, have been implemented within Angola by the government and NGOS, addressing stigmatizing concerns about abortion safety.

We break the individual and community levels out further into internalized, partner, friend, and community-wide attitudes, as each plays a different role in the creation of stigma. Internalized stigma refers the process of absorbing other people’s negative attitudes about abortion (Shellenberg & Tsui, 2012). Male heads of household may use their authority to compel their partners to continue a pregnancy or have an abortion (Schuster, 2005, Tsui et al., 2011). In turn, pregnancy may be concealed from partners, especially if they know their partners do not approve of abortion or will exert paternal rights in an undesirable fashion (Rossier, 2007). Outside these circumstances, male partners are likely to be the first to know of an unintended pregnancy. Female friends are often next to know of unintended pregnancies (Rossier, Guiella, Ouédraogo, & Thiéba, 2006). Friends are also often relied upon for contraceptive knowledge, connection to abortion resources, and support around reproductive health (Agadjanian, 1998, Baker and Khasiani, 1992, Sims, 1996).

2.3. Stigma, abortion, and contraception

Per Norris et al., abortion is stigmatized in part because it separates procreation from female sexuality, complicating ideals of women’s sexuality and womanhood (Norris et al., 2011). Contraception generally attracts less violent protest and outcry than abortion, but it similarly divorces sexuality from compulsory procreation. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there is no other literature that assesses how social attitudes towards contraception influence abortion stigma.

2.4. The purpose of this paper

This study seeks specifically to elucidate the relationship between perceived contraceptive attitudes and abortion stigma in Luanda, Angola. The motivation behind this investigation is twofold: first, to shed light on abortion attitudes in Angola, about which little literature has been published; second, to assess the impact of perceived social attitudes about contraception on abortion stigma. To do this, we analyzed survey data gathered in Luanda Province, Angola from women of reproductive age, which asked women how they thought their partners, friends, and communities felt about contraception. The same women were also asked questions to assess their level of abortion stigma, as measured by willingness to help someone get an abortion, willingness to help someone who was sick after an abortion, and desire to not talk about abortion experiences. The indirect questioning was employed due to reduce social desirability bias due to the illegality of abortion in Angola (Fisher, 1993). Similar questions have been employed to examine stigma among people living with HIV, measuring individual attitudes, social distance, felt normative and stigma perceived by people with HIV (Kang, Delzell, & Mbonyingabo, 2017). There are no abortion attitude-focused interventions currently in place in Angola, and given the legal framework, the likelihood of such interventions is low. However, contraceptive interventions are relatively well-established and supported by the government. Angola has a low modern contraceptive prevalence at 13.3% among all women, with condoms being the most prevalent method in Luanda (Instituto Nacional de Estatística - INE/Angola, Minstério da Saúde - MINSA/Angola, & ICF, 2017). The country is also plagued by high maternal mortality ratio at 477 per 100,000 live births (World Health Organization, 2015), likely with a high contribution of unsafe abortion mortality. If changing perceived contraceptive attitudes is shown to influence abortion stigma, existing contraception-focused interventions could be expanded to obliquely shift abortion attitudes as well as addressing family planning needs.

This investigation focuses on the mass culture, community, and individual levels to identify potential areas for additional or expanded interventions. Individual relationships are further broken out into friend and partner components, as partners and friends serve very different purposes in abortion disclosure and stigma. Based on these different roles, we separate the individual level into women’s relationships with friends and partners. An illustration of this expanded social-ecological model can be found in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Expanded Social-Ecological Model Adapted from Kumar et al. (2009).

2.5. Dimensions of stigma explored in this analysis

In our survey, we asked respondents “Would you do anything to help a friend or family member who needed to have a pregnancy terminated?”; “Is there anything you would do to help a friend or family member who terminated a pregnancy and still felt sick?”; and “If you, a friend, or a family member terminated a pregnancy, would you avoid telling other people?” . Each of the three items reflect different dimensions of stigmatization.

Cockrill and Nack build on Herek’s (2009) framework of three manifestations of sexual stigma to identify three manifestations of stigma for people who have abortions: internalized stigma, or negative beliefs about oneself based on cultural attitudes towards abortion; felt stigma, or perceptions of others’ negative attitudes towards abortion and anticipation of mistreatment based on those attitudes; and enacted stigma, or actions that reveal bias against abortion and those associated with it (Cockrill and Nack, 2013, Herek, 2009). Avoiding telling others about an abortion has been identified as a strategy to respond to felt stigma: by concealing abortion experiences, people who have abortions can avoid exposing themselves to the judgment and prejudice they might face if open with their stories (Cockrill & Nack, 2013). This strategy may also be used by friends and family of people who have abortions; by concealing their association with someone who has an abortion, they may avoid “courtesy stigma,” or stigma by association (Goffman, 1963, Norris et al., 2011). We asked respondents to assess the prevalence of silence as a stigma management strategy for both people who have abortions and their friends and family. Relatedly, we also inquire about whether respondents would help a friend or family member who needed to access abortion. There are more varied reasons an individual might refrain from helping a friend or family member access abortion. In restricted legal contexts, respondents might rightly fear punishment for their contact with illegal services; However, stigmatization of people who have abortions and potential fear of stigma may also play a role in not helping others access abortion.

In healthcare settings, abortion stigma negatively impacts post-abortion care: some providers refuse to provide post-abortion care at all due to religious or personal beliefs and stigmatization of people who have abortions (Rehnström Loi et al., 2015, Tagoe-Darko, 2013, Voetagbe et al., 2010). By asking respondents about whether they would help someone who was sick after an abortion, we seek to assess the prevalence of these attitudes amongst non-medical providers: how much of the population finds abortion to be so corrupting and compromising that they would refuse to help someone they’re close to access medical care? Given that Angolan law permits post-abortion care and demands no legal consequences for those who support others in accessing care, this item assesses respondent intentions towards one form of enacted stigma: the denial of support because someone has had an abortion.

3. Data and methods

This analysis uses data from the 2012 Angolan Community Survey. This survey, modeled after the Women’s Questionnaire of the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) and incorporating adapted sections of Angola’s Malaria Indicator Survey, collects information on women’s demographics and reproductive health. The survey collects not only data on family planning and pregnancy, but also asks a set of key questions pertaining to abortion. The survey was developed by a collaborative partnership between the University of California at Berkeley Bixby Center for Population Health and Sustainability and Population Services International (PSI) Angola, with SINFIC, a local marketing firm, carrying out the data collection. Ethical approval for this study was provided by the University of California, Berkeley Center for Protection of Human Subjects (CPHS #2011 08 3521) and by the Ethical Committee at the Instituto de Saude Publica in Luanda, Angola.

To ensure representative sampling, researchers used a multi-stage random sampling design to identify survey participants. First, sample size was distributed proportionately between municipalities based on municipality size. Then, researchers randomly selected sampling points within each municipality in Luanda and recruited a fixed number of participants from each sampling point. The survey was administered verbally by trained staff; surveying took place in private to reduce social desirability bias. Between October and November 2012, 1,545 Luandan women of reproductive age (ages 15–49) completed the survey, and a total of 1,469 answered all questions pertinent to this study.

3.1. Outcome variables

Three questions on the survey address abortion stigma. The first question, “Would you do anything to help a friend or family member who needed to have a pregnancy terminated? What?” offered respondents the option of stating whether they would take their friend or family member to a healthcare provider, to a pharmacist, do nothing, or “other.” The majority of “other responses” indicated that respondents would counsel their friend or talk to her parents, or that their response would depend on the circumstance of the pregnancy. A minority of “other” responses indicated that they did not know what they would do in such a situation. Given that the primary research question for this study was related to abortion stigma rather than healthcare provider selection, all answers were recoded into a yes/no binary response to “Would you do anything to help a friend or family member who needed to have a pregnancy terminated?” The responses that indicated a firm “no” were coded as “Would do nothing to help;” all other responses were coded as “Would do something to help.”

The next question in the sequence asked, “Is there anything you would do to help a friend or family member who terminated a pregnancy and still felt sick? What?” Similar to the previous question, respondents could reply that they would take their friend or family member to a healthcare provider, to a pharmacist, do nothing, or “other.” “Other” responses in this case were very similar to those for the above question: a majority of respondents who answered “other” would speak to their friend’s family members, or that they were not sure what they would do. A minority indicated that they would assess her condition or that it depended on the circumstances. As above, these responses were recoded into a binary response: would you do something to help a friend or family member who terminated a pregnancy and still felt sick, or would you not?

The final stigma-pertinent survey question addressed issues of silence and shame: “If you, a friend, or a family member terminated a pregnancy, would you avoid telling other people?” In this case, respondents indicated either that they would avoid telling people, that they would not avoid telling people, or that they were not sure. As above, this was recoded into a binary variable to better reflect the answers that clearly indicated that stigma could be relevant: either respondents were definite that they would not avoid telling other people, or they were not.

3.2. Predictor variables

Age, having ever given birth, and marital status were highly collinear; hypothesizing that the relatively recent conclusion of the civil war might contribute to a cohort effect, we selected age as the measure to include in the model. Education was broken into four categories: no education, primary education, secondary education, and university education or higher. Whether women were currently using a form of family planning, whether women were currently pregnant, and whether women stated they had ever terminated a pregnancy were also included as demographic controls. Though some definitions of family planning include abortion, interviews conducted with Angolan women during the development of this survey indicated that they saw “family planning program” as pregnancy prevention intervention using contraceptive methods and thus did not consider abortion to be part of family planning. This reflects similar findings in the literature which suggest that contraception is viewed independently of abortion (Tsui et al., 2011). Accordingly, survey questions asked about “family planning” and “contraception” interchangeably.

A woman’s perception of her partner’s views of family planning was measured through responses to three statements. Responses to the first, “Would you say that using contraception is mainly your decision, mainly your husband’s/partner’s/boyfriend’s decision, or did you both decide together?” were coded as binary variables: either her partner was involved in the decision-making (responses indicating mainly partner’s decision or decided together), or partner was not involved (respondent’s decision alone). Responses to the second, “Do you think that your husband/partner/boyfriend approves or disapproves of couples using a method to avoid pregnancy,” were coded as “approves” or “does not approve or respondent is unsure.” Responses to the third, “How often have you talked to your husband/partner/boyfriend about family planning in the past year?” were kept as they were in the survey: respondents could either answer “never,” “one or two times,” or “more often [than one or two times].” Agreement with the statement “Do you think that your husband/partner/boyfriend approves or disapproves of couples using a method to avoid pregnancy?” was initially measured in a five-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree,” and was recoded to three “agree, neutral, disagree” categories.

Three survey items addressed the role of friends’ perceived attitudes towards family planning. Due to high collinearity between the three variables, however, only one, “My friends encourage me to use family planning,” was selected for inclusion in the model as the indicator for the role of friends. Responses to these questions were on the previously mentioned five-point scale, and similarly recoded into three categories.

Perceived community attitudes were measured on the same five-point agree-disagree scale discussed above. “In my community, using contraception to prevent a pregnancy is accepted;” “Elders in my community support women using family planning;” “In my community, men do not like their wives to use family planning;” “In my community, a woman who uses modern methods of contraception is seen as an unfaithful wife.” Because agreement with these last two statements indicated a community that disapproved of family planning while agreement with the first two indicated a community that approved of family planning, these last two variables were reverse coded for analysis. The five-point responses were then recoded to the same three categories as above.

Exposure to family planning in media was measured through three binary variables indicating yes/no responses to a series of three questions: “In the last few months have you heard about family planning on the radio?”; “In the last few months have you seen something about family planning on the television?”; “In the last few months have you read about family planning in a newspaper or magazine?” Due to skip logic within the survey, 72 women who stated they were unable to become pregnant did not respond to these three questions.

3.3. Methods

Bivariate analyses were conducted to investigate the association between co-variates and each outcome. Multivariable logistic regression was conducted separately for each of the three outcome variables, using the following methodology: Models for each outcome variable were built in a stepwise fashion following the framework laid out in the social-ecological model above, moving from proximal to distal factors. First, a set of demographic explanatory variables were regressed on each outcome variable. Variables that demonstrated statistical significance at or below p < 0.2 were retained and added to the next model, which incorporated friend attitude variables. The same process was undertaken for each level of the socio-ecological model, with variables with statistical significance at or below p < 0.2 retained for the last model, which incorporated variables pertaining to media representation of family planning.

4. Results

4.1. Description of sample

As shown in Table 1, the majority of participants were less than 30 years old. Roughly 42% of participants had completed their education with primary school, while another 41% had gone as far as secondary school. Forty-five percent were actively using a contraceptive method to avoid or delay getting pregnant, and approximately 10% of respondents reported they had interrupted a pregnancy in the past. Less than half of respondents (42%) stated they would help a friend or family member who needed a pregnancy terminated; however, 87% stated they would help if that person were sick following a pregnancy termination (data not shown). Only 36% of women affirmatively stated that they would not avoid telling people about an abortion (data not shown).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the study sample according to abortion stigma variables among women of reproductive age in Luanda, Angola.

|

Would you do anything to help a friend or family member who needed to have a pregnancy terminated? |

Is there anything you would do to help a friend or family member who terminated a pregnancy and still felt sick? |

If you, a friend, or a family member terminated a pregnancy, would you avoid telling other people? |

Total (N = 1545) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Yes (%) | Chi-square p-value | Yes (%) | Chi-square p-value | No (%) | Chi-square p-value | % |

| Agea | 0.027 | 0.002 | 0.636 | ||||

| 15–19 years | 44.3 | 80.9 | 34.1 | 29.3 | |||

| 20–24 years | 48.2 | 89.5 | 34.1 | 23.4 | |||

| 25–29 years | 38.0 | 87.2 | 40.3 | 16.7 | |||

| 30–34 years | 36.2 | 90.3 | 37.7 | 13.4 | |||

| 35–39 years | 37.0 | 90.4 | 39.3 | 8.8 | |||

| 40–44 years | 36.7 | 83.5 | 34.2 | 5.1 | |||

| 45–49 years | 36.0 | 92.0 | 36.0 | 3.2 | |||

| Education | 0.286 | 0.226 | 0.642 | ||||

| No education | 40.0 | 82.5 | 37.5 | 2.6 | |||

| primary | 41.1 | 84.9 | 34.9 | 41.9 | |||

| secondary | 44.3 | 87.4 | 38.0 | 41.2 | |||

| university or higher | 37.1 | 89.6 | 34.4 | 14.3 | |||

| Pregnant now | 0.062 | 0.720 | 0.866 | ||||

| No/don’t know | 42.5 | 86.6 | 36.2 | 92.0 | |||

| Yes | 33.9 | 85.5 | 35.5 | 8.0 | |||

| Has had abortion | 0.031 | 0.106 | 0.287 | ||||

| No | 40.9 | 86.1 | 36.6 | 90.2 | |||

| Yes | 50.0 | 90.8 | 32.2 | 9.8 | |||

| Using family planning now | 0.010 | 0.106 | 0.299 | ||||

| No | 38.4 | 85.1 | 37.5 | 48.2 | |||

| Yes | 44.9 | 87.9 | 35.0 | 51.8 | |||

Missing 4 values were not included in calculations.

Partner, community and media variables are explored in Table 2. Partners were involved with family planning decision-making for roughly half of the respondents (52%). Similarly, about half of women (52%) reported that their partners encouraged them to use contraception, while only 21% reported that their partner did not encourage contraceptive use. Around 42% of women stated they had not spoken to their partner about family planning in the past year; the remainder of women were approximately evenly split between having spoken to their partner a few times and having spoken to them more frequently.

Table 2.

Partner, community and media exposure characteristics according to abortion stigma variables among women of reproductive age in Luanda, Angola.

|

Would you do anything to help a friend or family member who needed to have a pregnancy terminated? |

Is there anything you would do to help a friend or family member who terminated a pregnancy and still felt sick? |

If you, a friend, or a family member terminated a pregnancy, would you avoid telling other people? |

Total (N = 1545) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Yes (%) | Chi-square p-value | Yes (%) | Chi-square p-value | No (%) | Chi-square p-value | % |

| Partner involved in family planning decision-making | 0.497 | 0.000 | 0.09 | ||||

| Partner not involved | 40.9 | 82.2 | 38.3 | 47.8 | |||

| Partner involved | 42.6 | 90.5 | 34.2 | 52.2 | |||

| How many times spoken with partner about family planning in last year | 0.000 | 0.085 | 0.644 | ||||

| Never | 41.4 | 84.4 | 36.7 | 42.3 | |||

| 1–2 times | 50.5 | 87.3 | 37.3 | 27.4 | |||

| More than 1–2 times | 34.5 | 88.9 | 34.5 | 30.2 | |||

| Partner encourages contraceptive use | 0.223 | 0.005 | 0.183 | ||||

| Completely dis/disagree | 41.2 | 87.1 | 33.0 | 20.6 | |||

| Indifferent | 38.6 | 82 | 34.5 | 27.0 | |||

| Agree/completely agree | 43.7 | 88.6 | 38.3 | 52.4 | |||

| Partner opinion on family planning | 0.024 | 0.001 | 0.812 | ||||

| Disapproves | 38.8 | 83.4 | 36.5 | 47.2 | |||

| Approves | 44.5 | 89.3 | 35.9 | 52.8 | |||

| Friends encourage using family planning | 0.203 | 0.000 | 0.032 | ||||

| Completely dis/disagree | 43.0 | 85.6 | 40.1 | 17.9 | |||

| Indifferent | 38.1 | 81.3 | 31.2 | 27.0 | |||

| Agree/completely agree | 43.2 | 89.4 | 37.4 | 55.1 | |||

| Using contraception to prevent a pregnancy is accepted | 0.000 | 0.198 | 0.212 | ||||

| Completely dis/disagree | 64.3 | 88.3 | 40.3 | 10.0 | |||

| Indifferent | 36.2 | 83.7 | 32.7 | 22.2 | |||

| Agree/completely agree | 40.4 | 87.2 | 36.7 | 67.8 | |||

| Men like their wives to use family planning | 0.005 | 0.741 | 0.024 | ||||

| Completely dis/disagree | 42.2 | 87.2 | 38.1 | 46.0 | |||

| Indifferent | 37.3 | 85.7 | 31.6 | 34.4 | |||

| Agree/completely agree | 48.8 | 86.5 | 39.6 | 19.6 | |||

| Women who use modern methods of contraception are not seen as an unfit wives | 0.079 | 0.019 | 0.004 | ||||

| Completely dis/disagree | 45.6 | 86.1 | 40.2 | 34.5 | |||

| Indifferent | 38.9 | 83.4 | 30.1 | 28.8 | |||

| Agree/completely agree | 40.6 | 89.4 | 37.2 | 36.7 | |||

| Elders support women using family planning | 0.000 | 0.184 | 0.052 | ||||

| Completely dis/disagree | 48.0 | 87.5 | 37.8 | 19.7 | |||

| Indifferent | 31.9 | 84.6 | 32.6 | 40.8 | |||

| Agree/completely agree | 49.0 | 88.0 | 39.0 | 39.5 | |||

| Heard about family planning on radioa | 0.000 | 0.021 | 0.024 | ||||

| Yes | 51.1 | 89.2 | 32.9 | 35.2 | |||

| No | 36.5 | 84.9 | 38.9 | 64.8 | |||

| Heard about family planning on televisiona | 0.000 | 0.006 | 0.275 | ||||

| Yes | 49.2 | 89.1 | 38.3 | 45.0 | |||

| No | 35.4 | 84.2 | 35.6 | 55.0 | |||

| Read about family planning in newspaper/magazinea | 0.000 | 0.054 | 0.069 | ||||

| Yes | 53.9 | 89.4 | 32.8 | 24.4 | |||

| No | 37.6 | 85.4 | 38.1 | 75.6 | |||

Missing 72 values were not included in calculations.

The majority of women (55%) agreed that their friends encouraged them to use family planning. Sixty-eight percent of respondents reported that using contraception to prevent pregnancy was accepted in their communities, though 46% of respondents thought men in their communities did not like their wives to use family planning (Table 2).

Family planning media exposure was somewhat limited: 65% of respondents had not heard about family planning on the radio in the past few months. Similarly, 55% of respondents had not seen anything about family planning on television, and 76% had not read about family planning in newspapers or magazines (Table 2).

4.2. Bivariate analyses

Abortion history or family planning use was associated with helping others who needed an abortion (Table 1). The frequency with which women spoke to their partners about family planning was associated with women’s desire to help those in need of an abortion (p < 0.001), as was partner opinion on family planning (p = 0.024) (Table 2). Whether a partner was involved in family planning decision-making (p < 0.001), partner encouragement of contraceptive use (p = 0.005), and partner opinion on family planning were associated with helping others who were sick following a pregnancy termination (p = 0.001) (Table 2).

Perceived community acceptance of contraception (p < 0.001), men’s views on their wives’ use of family planning (p = 0.005), and elders’ views of women using contraception (p < 0.001) were all associated with helping people who needed an abortion (Table 2). Perceived community beliefs about whether women who use contraception are unfit wives was associated with helping someone who was sick after an abortion (p = 0.019) (Table 2). These beliefs, in addition to men’s perceived preferences regarding their wives’ use of family planning and elders’ perceived views on family planning, were associated with whether or not women would mention abortion experiences to others (Table 2).

Exposure to family planning information on radio, television, and newspaper or magazine was associated with whether women would help friends needing abortions; for helping sick friends, radio and television were associated; for discussing abortion experiences, only radio demonstrated a statistically significant association (Table 2).

4.3. Multivariable analysis

Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 present the model-building process and final logistic regression models for each of the three outcome variables on abortion stigma. Aside from age, the only sociodemographic variable that demonstrated a significant association for any of the three outcomes was having terminated a pregnancy, which had a positive effect on respondents’ likelihood to state they would help a friend who needed an abortion (OR 1.60, 95% CI 1.11–2.32) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors associated with whether a woman would help a friend needing an abortion in Luanda, Angola.

| Variable | Odds Ratio | [95% Conf. Interval] | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Would help friend needing abortion | |||

| Age | |||

| 15–19 years | – | Reference | |

| 20–24 years | 0.95 | 0.69–1.29 | 0.728 |

| 25–29 years | 0.52 | 0.36–0.75 | 0.001 |

| 30–34 years | 0.51 | 0.34–0.76 | 0.001 |

| 35–39 years | 0.59 | 0.37–0.93 | 0.024 |

| 40–44 years | 0.49 | 0.27–0.89 | 0.020 |

| 45–49 years | 0.56 | 0.26–1.18 | 0.126 |

| Abortion | |||

| Has not had abortion | – | Reference | |

| Has had abortion | 1.60 | 1.11–2.32 | 0.013 |

| How many times spoken with partner about family planning in last year | |||

| Never | – | Reference | |

| 1–2 times | 1.25 | 0.92–1.7 | 0.153 |

| More than 1–2 times | 0.64 | 0.46 - 0.88 | 0.006 |

| Partner approval | |||

| Partner does not approve of family planning | – | Reference | |

| Partner approves of family planning | 1.34 | 1.03–1.73 | 0.026 |

| Using contraception to prevent a pregnancy is accepted | |||

| Completely disagree/disagree | – | Reference | |

| Indifferent | 0.40 | 0.26–0.62 | < 0.001 |

| Agree/completely agree | 0.36 | 0.25–0.53 | < 0.001 |

| Elders in community support women using family planning | |||

| Completely dis/disagree | – | Reference | |

| Indifferent | 0.57 | 0.42–0.78 | < 0.001 |

| Agree/completely agree | 1.12 | 0.83–1.52 | 0.458 |

| Heard about family planning on television | 0.66 | 0.52–0.83 | 0.001 |

| Read about family planning in newspaper/magazine | 0.56 | 0.42–0.74 | < 0.001 |

Table 4.

Factors associated with whether woman would help a friend in need of medical attention post- abortion in Luanda, Angola.

| Variable | Odds Ratio | [95% Conf. Interval] | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Would help sick friend post-abortion | |||

| Age | |||

| 15–19 years | – | Reference | |

| 20–24 years | 1.72 | 1.13–2.62 | 0.01 |

| 25–29 years | 1.28 | 0.80–2.03 | 0.30 |

| 30–34 years | 1.65 | 0.96–2.85 | 0.07 |

| 35–39 years | 1.60 | 0.83–3.12 | 0.16 |

| 40–44 years | 0.79 | 0.37–1.67 | 0.54 |

| 45–49 years | 1.90 | 0.56–6.43 | 0.30 |

| Partner involved in family planning decision making | 1.86 | 1.35–2.57 | 0.00 |

| Friends encourage using family planning | |||

| Completely dis/disagree | – | Reference | |

| Indifferent | 0.89 | 0.57–1.39 | 0.59 |

| Agree/completely agree | 1.43 | 0.93–2.20 | 0.11 |

| Women who use modern methods of contraception are not seen as an unfit wives | |||

| Completely dis/disagree | – | Reference | |

| Indifferent | 1.14 | 0.77–1.68 | 0.53 |

| Agree/completely agree | 1.48 | 1.00–2.17 | 0.05 |

| Have seen something about family planning on television | 0.68 | 0.49–0.93 | 0.02 |

Table 5.

Factors associated with whether a woman would not avoid telling people about abortion in Luanda, Angola.

| Variable | Odds Ratio | [95% Conf. Interval] | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Would not avoid telling people about abortion | |||

| Partner encourages contraceptive use | |||

| Completely dis/disagree | – | Reference | |

| Indifferent | 1.39 | 0.98–1.97 | 0.06 |

| Agree/completely agree | 1.42 | 1.04–1.94 | 0.03 |

| Friends encourage using family planning | |||

| Completely dis/disagree | – | Reference | |

| Indifferent | 0.63 | 0.44–0.91 | 0.01 |

| Agree/completely agree | 0.73 | 0.53–1.01 | 0.06 |

| Women who use modern methods of contraception are not seen as an unfit wives | |||

| Completely dis/disagree | – | Reference | |

| Indifferent | 0.68 | 0.50–0.91 | 0.01 |

| Agree/completely agree | 0.84 | 0.65–1.08 | 0.18 |

| Heard about family planning on radio | 1.57 | 1.21–2.04 | 0.00 |

| Heard about family planning on television | 0.74 | 0.58–0.95 | 0.02 |

Partner-related variables played a significant role in each of the models, but manifested differently. Having a partner that approves of family planning had a positive effect on likelihood to help a friend who needed an abortion (OR 1.34, CI 1.03–1.73) (Table 3), while having a partner involved in family planning decision-making had a positive effect on likelihood to help a sick friend post-abortion (OR 1.86, CI 1.35–2.57) (Table 4). Women were more likely to not hide experiences of abortion if they responded positively to the statement “My husband encourages me to use family planning” (OR 1.42, CI 1.04–1.94) (Table 5).

Whether friends encouraged respondents to use family planning was not associated with women stating they would help a friend who needed an abortion (data not shown), or a friend sick after an abortion (Table 4). However, friends’ indifference to family planning use was statistically significantly negatively associated with telling people about an experience of abortion (Table 5).

Community factors played a role in each final model. Agreement that the community accepts contraception had a negative association with helping a friend in need of an abortion (OR 0.36, CI 0.25–0.53), as did indifference to the statement (OR .40, CI 0.26–0.62) (Table 3). Indifference to the statement that elders support women using family planning also had a statistically significant negative association (OR 0.57, CI 0.42–0.78) (Table 3). Agreement that women who use modern methods of contraception are not seen as unfit wives in the community had a positive association with helping a sick friend after an abortion, relative to disagreement (OR 1.48, CI 1.00–2.17) (Table 5).

Finally, media had a significant association with two of the three outcome variables. Family planning exposure in newspapers and magazines had a negative effect on desire to help an abortion-seeking friend (OR 0.56, CI 0.42–0.74), as did seeing something on television about family planning (OR 0.66, CI 0.52–0.83) (Table 3). Family planning exposure on television also had a negative effect on openness about abortion (OR 0.74, CI 0.58–0.95). Family planning exposure through the radio had the only positive effect of all media variables, leading to a 1.57 increase in odds of abortion openness (CI 1.21–2.04).

5. Discussion

These data, unprecedented in the literature on abortion in Angola, represent a new opportunity to identify Luandan women’s attitudes towards abortion. Specifically, this study enabled investigation and identification of various social factors that may influence abortion stigma. Though all three outcome variables addressed abortion stigma in different ways, each spoke to a different aspect or degree of stigma. Refusal to assist someone in receiving an abortion might have been a reflection of any number of cultural or religious beliefs opposing abortion; refusal to assist someone who needs medical care after an abortion may indicate a far more censorious, and hence less prevalent, attitude towards abortion. Respondents’ attitudes towards these measures support this interpretation: while 42% of respondents would help a friend or family member acquire an abortion, more than twice as many would assist if medical care was needed post-abortion. This finding may represent not only stigma but fear of encountering legal consequences for helping someone acquire an abortion. It also reflects poor understanding of absence of legal consequences for post-abortion care, a service available in Angola as part of a Government health program. Responses to the question “If you, a friend, or a family member terminated a pregnancy, would you avoid telling other people?” speak to the silencing effects of stigma and abortion in a social context; avoidance of telling people about abortion experiences might indicate fear of social disapprobation as much as it might indicate respondent attitudes towards abortion.

A more recent discussion of abortion stigma has focused on finding “edges of abortion stigma versus stigma associated with unwanted or mistimed pregnancies”(Kumar, 2013). These edges may shed light on some of the results. For example, media discussion and perceived community acceptance of family planning decrease likelihood to help someone get an abortion. Potentially, these results indicate not shame at abortion itself, but shame at the unintended pregnancy that leads to the abortion. This idea of “shameful pregnancy” as the primary source of shame in some abortions has been documented in Ghana, Burkina Faso, and Cameroon, where educated women see abortion as a “lesser shame” than a mistimed unintended pregnancy (Bleek and Asante-Darko, 1986, Johnson-Hanks, 2002, Rossier, 2007). In this construction, shameful pregnancy is the primary focus of stigma; abortion is tainted by association, but is not itself inherently objectionable. Abortion stigma in this study may therefore stem from the belief that, in a social context that supports family planning usage, unintended pregnancy (shameful pregnancy) is expected to be easily avoided. Hence, increased social support for family planning increases the shame in shameful pregnancy, and increases abortion stigma by proxy.

Results seem to indicate that increased partner engagement in family planning (as measured by involvement and frequency of communication) is associated with a reduced likelihood to help a friend or family member receive an abortion, as well as a reduced likelihood to discuss an abortion experience. However, partner support of family planning demonstrates (as measured in encouragement and approval) the opposite effect, increasing communication about abortion experiences and likelihood to assist someone in need of an abortion. Attitudes towards contraception likely play a role here; engagement in family planning does not indicate approval of family planning, and partners who disapprove of family planning could easily express those opinions through family planning discussion and decision-making conversations. In contrast, partner support of family planning inherently indicates that partners are in favor of family planning. Thus, increasing partner support of family planning, not just engagement in family planning, may be one avenue to decrease abortion stigma.

The role of media discussion of family planning merits further investigation. Exposure to family planning via television and newspaper was associated with statistically significant and negative effects on willingness to help someone access an abortion, and seeing something on television about family planning similarly reduced likelihood to help a friend who got sick after an abortion and speak about an abortion experience. However, exposure to family planning information via the radio led to a statistically significant 1.57 increased odds of speaking about abortion experience. While this may indicate that increased radio discussion of family planning may increase discussion of abortion experiences, further research should investigate why radio, but not television, demonstrates this effect, what content yields effects, and which demographics consume which forms of media.

With a few exceptions, the results for likelihood to help a friend or family member get an abortion and likelihood to be open about abortion experiences indicate similar concepts: social support of family planning may increase abortion stigma, as may partner involvement in family planning, while partner support of family planning may decrease stigma. Results for likelihood to help a friend or family member who is sick after an abortion, however, diverge from the other outcomes. In the final model for this outcome, only three variables had a positive effect and were statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05. An increase in age from 15–19 to 20–24 years was associated with an increase in likelihood to assist someone in need of medical help, as were having a partner involved in family planning decision-making and disagreement with the statement that women who use modern methods of contraception are seen as unfit wives. One reason these results may differ from the other two outcomes is the relative extremity of refusing to help someone who needs medical attention after an abortion. The religious, cultural, political, and personal factors that would lead to this relatively extreme view may not be captured in the models constructed in this study, which focused primarily on the role of perceived contraceptive attitudes. These results may also be partially explained by increased trust of or engagement with health services, leading respondents to be more likely to believe medical care would be trustworthy and/or useful for those suffering from complications post-abortion. Further research could focus on what characterizes the small portion of the sample that would decline to assist a friend or family member in medical need, to assess factors that contribute to that attitude.

Having terminated a pregnancy was significantly and positively associated with helping a friend who needed to have an abortion. However, it should be noted that in addition to stigma abortion, language choice affects reporting of pregnancy termination. In one study in the Philippines, 16.6% of women reported having had an abortion, 12.2% acknowledged having “induced menstruation,” but only 4.4% stated they had interrupted a pregnancy (Ahman & Shah, 2011). Survey self-reports of pregnancy termination are also known to be unreliable and prone to underreporting, especially in verbal responses (Fu, Darroch, Henshaw, & Kolb, 1998). The phrasing of this question, as well as the known factor of abortion underreporting in surveys, potentially underestimates the magnitude of the effect of a past abortion experience.

This study has a number of limitations. Evidence suggests that religiosity plays a role in attitudes towards abortion, and the data included no measures to assess religiosity, nor to meaningfully assess women’s own approval or disapproval of family planning. While women were asked whether they were single, married, or divorced, unmarried women were asked their civil marital status, but not relationship status, which may have yielded different results. Questions pertaining to media did not ask whether family planning was positively or negatively represented in the media, just whether it was represented. Respondents might have been more likely to report media exposure to family planning if they were currently using contraception; similarly, respondents who are currently using contraception might be more likely to perceive approval or disapproval from their communities, friends, or partners. As all respondents answered the partner-related questions, responses to the partner-related questions may include responses from single women who are responding in the hypothetical, rather than speaking about their current relationship; additionally, several types of partners—husbands, partners, and boyfriends—were asked about as one group, while their role and importance may vary depending on which one of those categories they fit into, in this study we were interested in the views of an intimate partner regardless of their status. All respondents were selected from Luanda province sampling points, so results likely differ from similar women in other urban areas or rural Angolan populations. Interpretation of these results must consider that all responses reflected the perceptions of the respondents, which may not accord with reality: for example, a respondent could assert that elders in her community support family planning when the opposite is true. Finally, the three questions used to assess abortion stigma were not based on validated measures of abortion stigma, and may not accurately capture the extent or nature of abortion stigma in the sample.

6. Conclusion

By silencing abortion experiences, limiting women's access to social support about pregnancy termination, and restricting access to networks of care, abortion stigma endangers women’s health. As Angola strives to further reduce its maternal mortality rate, abortion stigma reduction must become a priority. Results from this study indicate new avenues to move forward in developing interventions to reduce stigma. Because of the lesser stigma associated with contraception, interventions aimed at increasing support of contraception may provide a socially acceptable approach for reducing abortion stigma by proxy; the results of this study indicate that targeting women’s partners may be a particularly fruitful approach. Other results, which suggest that community and friend support of contraception may unexpectedly contribute to abortion stigma, indicate that stigma interventions should extend beyond abortion, to reduce social stigma about unintended or “shameful” pregnancy. By reducing the stigmatization of women’s reproductive decision-making, Angola has the potential to prevent the deaths, and support the lives, of its women.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

References

- Agadjanian V. “Quasi-Legal” abortion services in a sub-saharan setting: Users' profile and motivations. International Family Planning Perspectives. 1998:111–116. [Google Scholar]

- Ahman, E., & Shah, I. (2011). Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2008.

- Baker J., Khasiani S. Induced abortion in Kenya: Case histories. Studies in Family Planning. 1992;23(1):34–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baklinski, T. (2012). Catholic Bishops of Angola oppose move to decriminalize abortion. Retrieved from 〈https://www.lifesitenews.com/news/catholic-bishops-of-angola-oppose-move-to-decriminalize-abortion〉.

- Bingham A., Drake J.K., Goodyear L., Gopinath C., Kaufman A., Bhattarai S. The role of interpersonal communication in preventing unsafe abortion in communities: The dialogues for life project in Nepal. Journal of Health Communication. 2011;16(3):245–263. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.529495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleek W., Asante-Darko N. Illegal abortion in Southern Ghana: Methods, motives and consequences. Human Organization. 1986;45(4):333–343. [Google Scholar]

- Bloemen, S. (2010). Brick by brick and doctor by doctor, Angola rebuilds its healthcare system. Retrieved from 〈http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/angola_54038.html〉.

- Brookman-Amissah E., Moyo J.B. Abortion law reform in Sub-Saharan Africa: No turning back. Reproductive Health Matters. 2004;12(sup24):227–234. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(04)24026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Central Intelligence Agency (2014). The World Factbook: Angola. Retrieved from 〈https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ao.html〉.

- Cockrill K., Nack A. “I’m not that type of person”: Managing the stigma of having an abortion. Deviant Behavior. 2013;34(12):973–990. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison M.A. Authoritative knowledge and single women’s unintentional pregnancies, abortions, adoption, and single motherhood: Social stigma and structural violence. Med Anthropol Quarterly. 2003;17(3):322–347. doi: 10.1525/maq.2003.17.3.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher R.J. Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect questioning. Journal of Consumer Research. 1993;20(2):303–315. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman L., Landy U., Darney P., Steinauer J. Obstacles to the integration of abortion into obstetrics and gynecology practice. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2010;42(3):146–151. doi: 10.1363/4214610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu H., Darroch J.E., Henshaw S.K., Kolb E. Measuring the extent of abortion underreporting in the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth. Family Planning Perspectives. 1998:128–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Jenkins, JH & Carpenter; 1963. Stigma: Notes on a spoiled identity. [Google Scholar]

- Goyaux N., Yacé-Soumah F., Welffens-Ekra C., Thonneau P. Abortion complications in abidjan (Ivory Coast) Contraception. 1999;60(2):107–109. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(99)00070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijnders M., Van Der Meij S. The fight against stigma: An overview of stigma-reduction strategies and interventions. Psychology, Health Medicine. 2006;11(3):353–363. doi: 10.1080/13548500600595327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek G.M. Sexual stigma and sexual prejudice in the United States: A conceptual framework. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation. 2009;54:65–111. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-09556-1_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Committee (2013). Center for civil political rights: Overview of the 107th session of the human rights committee. Retrieved from 〈http://ccprcentre.org/ccpr-overview-of-sessions?/publication/overview-of-the-sessions/107-session-overview/#3〉.

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística - INE/Angola, Minstério da Saúde - MINSA/Angola, & ICF (2017). Angola Inquérito de Indicadores Múltiplos e de Saúde (IIMS) 2015–2016. Retrieved from Luanda, Angola: 〈http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR327/FR327.pdf〉.

- Johnson-Hanks J. The lesser shame: Abortion among educated women in southern Cameroon. Social Science Medicine. 2002;55(8):1337–1349. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang E., Delzell D.A.P., Mbonyingabo C. Understanding HIV transmission and illness stigma: A relationship revisited in rural Rwanda. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2017;29(6):540–553. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2017.29.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassebaum N.J., Bertozzi-Villa A., Coggeshall M.S., Shackelford K.A., Steiner C., Heuton K.R.…Lozano R. Global, regional, and national levels and causes of maternal mortality during 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384(9947):980–1004. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60696-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimport K., Foster K., Weitz T.A. Social sources of women’s emotional difficulty after abortion: Lessons from women’s abortion narratives. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2011;43(2):103–109. doi: 10.1363/4310311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A. Everything is not abortion stigma. Women’States Health Issues. 2013;23(6):e329–e331. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Hessini L., Mitchell E.M. Conceptualising abortion stigma. Culture, Health Sexuality. 2009;11(6):625–639. doi: 10.1080/13691050902842741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiga, S. (2012). Intercession report of the mechanism of the special rapporteur on the rights of women in Africa since its establishment. Retrieved from Cote d’Ivoire: 〈http://www.achpr.org/sessions/52nd/intersession-activity-reports/rights-of-women/〉.

- Major B., Gramzow R.H. Abortion as stigma: Cognitive and emotional implications of concealment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77(4):735–745. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.4.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngwena C. An appraisal of abortion laws in southern Africa from a reproductive health rights perspective. The Journal of Law, Medicine Ethics. 2004;32(4):708–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.2004.tb01976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris A., Bessett D., Steinberg J.R., Kavanaugh M.L., De Zordo S., Becker D. Abortion stigma: A reconceptualization of constituents, causes, and consequences. Women’States Health Issues. 2011;21(3):S49–S54. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Population Policy Data Bank(n.d.). Angola abortion policy. Retrieved from New York: 〈www.un.org/esa/population/publications/abortion/doc/angol1.doc〉.

- Rehnström Loi U., Gemzell-Danielsson K., Faxelid E., Klingberg-Allvin M. Health care providers' perceptions of and attitudes towards induced abortions in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia: A systematic literature review of qualitative and quantitative data. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):139. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1502-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossier C. Abortion: An open secret? Abortion and social network involvement in Burkina Faso. Reproductive Health Matters. 2007;15(30):230–238. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(07)30313-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossier C., Guiella G., Ouédraogo A., Thiéba B. Estimating clandestine abortion with the confidants method—results from Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Social Science Medicine. 2006;62(1):254–266. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis J.F., Owen N., Fisher E. Health behavior: Theory, research, and practice. 5th ed. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2015. Ecological models of health behavior; pp. 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Say L., Chou D., Gemmill A., Tuncalp O., Moller A.B., Daniels J.…Alkema L. Global causes of maternal death: A WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Global Health. 2014;2(6):e323–e333. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70227-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster S. Abortion in the moral world of the Cameroon grassfields. Reproductive Health Matters. 2005;13(26):130–138. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(05)26216-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedgh G., Bearak J., Singh S., Bankole A., Popinchalk A., Ganatra B.…Alkema L. Abortion incidence between 1990 and 2014: Global, regional, and subregional levels and trends. Lancet. 2016;388(10041):258–267. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30380-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shellenberg K.M., Tsui A.O. Correlates of perceived and internalized stigma among abortion patients in the USA: An exploration by race and Hispanic ethnicity. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2012;118(Suppl 2):S152–159. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(12)60015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, V.L. (2009). Pope calls for conversion from Witchcraft in Africa. Retrieved from 〈http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/03/21/AR2009032102157.html〉.

- Sims P. Oxford University Press; 1996. Abortion as a public health problem in Zambia. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S., Remez, L., Sedgh, G., Kwok, L., & Onda, T. (2018). Abortion worldwide 2017: Uneven progress and unequal access. Retrieved from New York: 〈https://www.guttmacher.org/report/abortion-worldwide-2017〉.

- Tagoe-Darko E. “Fear, shame and embarrassment”: The stigma factor in post abortion care at Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital, Kumasi, Ghana. Asian Social Science. 2013;9(10):134. [Google Scholar]

- Tsui A.O., Casterline J., Singh S., Bankole A., Moore A.M., Omideyi A.K.…Shellenberg K.M. Managing unplanned pregnancies in five countries: Perspectives on contraception and abortion decisions. Global public health. 2011;6(sup1):S1–S24. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2011.597413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venture Strategies Innovations (2013). Expanding access to postabortion care services in Angola with the introduction of Misoprostol. Retrieved from Berkeley, CA: 〈http://www.vsinnovations.org/assets/files/Program%20Briefs/VSI_Angola%20MOH%20PAC%20Brief%202013%2006%2020F.pdf〉.

- Voetagbe G., Yellu N., Mills J., Mitchell E., Adu-Amankwah A., Jehu-Appiah K., Nyante F. Midwifery tutors' capacity and willingness to teach contraception, post-abortion care, and legal pregnancy termination in Ghana. Human Resources for Health. 2010;8(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-8-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2015). Trends in maternal mortality: 1990–2015: estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division (9241565144). Retrieved from Geneva: 〈http://www.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2017-05/trends-in-maternal-mortality-1990-to-2015.pdf〉.