Abstract

Purpose

The PARP inhibitor, Olaparib, is approved for women with BRCA- mutated ovarian cancer. Therefore there is an urgent need to test patients and obtain results in time to influence treatment. Models of BRCA testing such as the mainstreaming oncogenetic pathway, involving oncology health professionals are being used. The authors report on the establishment of the extended role of the clinical nurse specialist in consenting women for BRCA testing in routine gynaecology-oncology clinics using the mainstreaming model.

Methods

Nurses undertook generic consent training and specific counselling training for BRCA testing in the form of a series of online videos, written materials and checklists before obtaining approval to consent patients for germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations.

Results

Between July 2013 and December 2015, 108 women with ovarian cancer were counselled and consented by nurses in the medical oncology clinics at a single centre (The Royal Marsden, UK). This represented 36% of all ovarian cancer patients offered BRCA testing in the oncology clinics at the centre. Feedback from patients and nurses was encouraging with no significant issues raised in the counselling and consenting process.

Conclusion

The mainstreaming model allows for greater access to BRCA testing for ovarian cancer patients, many of whom may benefit from personalised therapy (PARP inhibitors). This is the first report of oncology nurses in the BRCA testing pathway. Specialist oncology nurses trained in BRCA testing have an important role within a multidisciplinary team counselling and consenting patients to undergo BRCA testing.

Introduction

The significance of germline BRCA (BReast CAncer susceptibility gene) testing in ovarian cancer to identify hereditary risks and clinical consequences has come to the forefront over the last few years. Moreover, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) (2014) and US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (2014) approval of olaparib (Lynparza) at the end of 2014, the first targeted therapy (PARP inhibitor) for BRCA mutation- associated ovarian cancer means that there is an urgent need to deliver more widespread BRCA testing in routine clinical practice. In England, from April 2016, patients with BRCA- mutated, platinum-sensitive ovarian, fallopian tube or primary peritoneal cancer who have had three or more courses of platinum-based chemotherapy can access olaparib through the NHS (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2016).

PARP inhibitors exploit the concept of ‘synthetic lethality’ targeting one of the genes in a synthetic lethal pair, where the other is defective (e.g. BRCA mutation), selectively kills tumour cells while sparing normal cells (thereby limiting toxicity) (Banerjee et al, 2010). The pivotal clinical trial that led to the licensing of the first PARP inhibitor, olaparib, is a double-blind, placebo-controlled randomised phase II study in which patients with platinum-sensitive, recurrent, high-grade serous ovarian cancer (who had achieved a response following their most recent platinum-based regimen) were randomised to either olaparib or placebo maintenance therapy. In a subgroup analysis, patients with a BRCA mutation were shown to have a significant benefit from olaparib compared with placebo, with an 82% improvement in progression-free survival (median progression-free survival (PFS) BRCA mutation group 11.2 vs 4.3 months; HR=0.18, 95% confidence interval, 0.10-0.31; p<0.0001) (Lederman et al, 2014).

Ovarian cancer is the fourth most common cause of cancer death for women in the UK, there were are over 7000 new cases and more than 4000 deaths in 2012/2013 (Cancer Research UK, 2016). It is now recognised that the incidence of BRCA germline mutations in epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is likely to be higher than previously believed (Moschetta et al, 2016).

In a study of 1001 patients, the overall incidence of germline BRCA mutations in non-mucinous EOC was 14.1%.The rate was even higher (17.1%) in patients with high-grade serous adenocarcinoma, which is the most common histological subtype It is particularly noteworthy that 44% of women with germ- line BRCA mutations did not report a relevant family history of cancer (Alsop et al, 2012).This means that up until recently, according to most international testing criteria, these women would not have been eligible for BRCA testing (George, 2015).

Knowledge of the germline BRCA mutation status not only provides important clinical information for the management of patients (prognostic information, predicting response to chemotherapy, access to PARP inhibitors, screening for breast cancer) but also has consequences for family members (cancer screening, consideration of prophylactic measures) who have a 50% risk of inheriting a BRCA mutation (Banerjee et al, 2010).

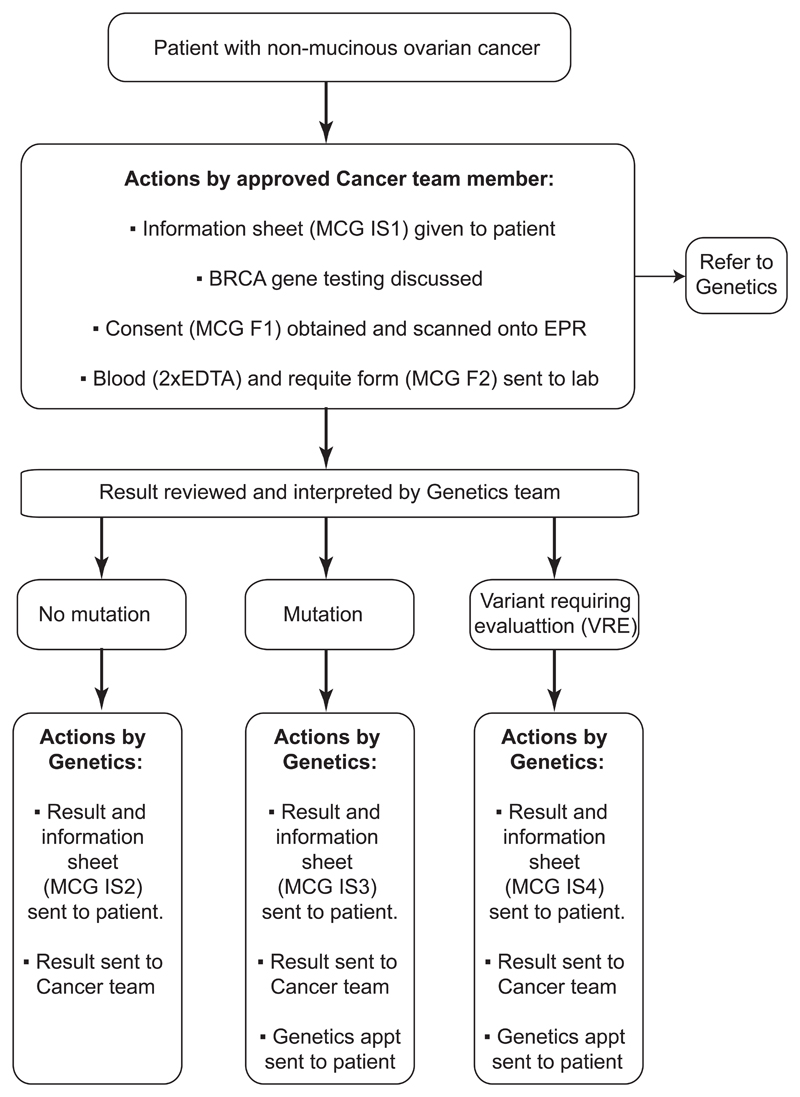

Up until recently, clinical practice for the majority of cancer patients worldwide was to be offered BRCA testing through referrals to the genetics team (Moschetta et al, 2016) However, there is a valid concern from genetics and oncology experts worldwide that the volume of patients who may benefit from BRCA testing may overwhelm current genetic services (Rahman, 2014; Slade et al, 2014). The time from the genetics referral to results has been in excess of 6 months (George, 2015). Therefore, innovative approaches to BRCA testing on a wider scale need to be considered, as the demand for BRCA testing is increasing among patients, family members and cancer clinicians. The Royal Marsden team piloted a new ‘oncogenetic pathway’ of BRCA testing in routine ovarian cancer clinical practice as part of the Mainstreaming Cancer Genetics Programme (MCG) (http://mcgprogramme.com), which aims to make genetic testing part of routine cancer patient care. In the pilot study, between July 2013 and January 2014, 119 women with serous or endometrioid ovarian cancer under the age of 65 were tested for BRCA mutations using the BRCA testing protocol in the medical oncology clinics (Figure 1). The BRCA mutation rate within this group of women was 16.8%. Strikingly, more than 50% of women tested had no family or personal history of breast or ovarian cancer and therefore under previous testing guidelines, would not have been eligible for BRCA testing (George et al, 2014).

Figure 1.

Ovarian cancer BRCA testing protocol

As an integral part of the oncology team, clinical nurse specialists (CNSs) are often the keyworkers for patients throughout the cancer pathway (Cook et al, 2015). The scope of practice of many advanced nurses is expanding (Gray, 2016) with many carrying out the necessary training and competencies to perform procedures such as ascetic drains, chemotherapy consent and HIV testing (Kwong and Gabler, 2015) in order to enhance the patient management pathway. Within oncology, many are now also consenting for trial screening, including testing for somatic and germline mutations to assess suitability for targeted treatments. The process of informed consent mandates for all areas, and focuses on giving patients sufficient information about the investigation or intervention to be able to make an informed decision about whether or not to proceed.

As new initiatives are developed, it is often appropriate for advanced nurses to become involved with service development to help meet patient needs, and address patient demands. In view of the fact that nurses already are active in consenting patients for other investigations having had appropriate consent training, the addition of BRCA consent and associated counselling to the nurse portfolios was an obvious extension. The CNSs were therefore asked to be key members of the gynaecology oncology team to help identify and consent women for BRCA gene mutations. The authors report the experience of CNSs delivering counselling and consent for germline BRCA testing in cancer patients.

Methods

This article provides a description of the nursing experience of BRCA testing and includes outcomes of questionnaires that were distributed to six gynaecology oncology CNSs who had completed the BRCA consent training to establish the nursing consensus of this advanced role within today’s practice. In addition, the patient experience of BRCA testing consent from nurses was obtained.

A service evaluation approved by the Royal Marsden Research and Development Committee, involving patient and health professionals completing an online questionnaire was carried out for the first 119 patients undergoing BRCA testing using the mainstreaming model (George et al, 2014). Oncology health professionals (consultants, trainees and nurses) were offered training delivered by the cancer genetics team on germline BRCA testing. CNSs who had completed the hospital general consent training were offered the opportunity to take on this new role, with appropriate provision of training and support from the oncology and genetic teams.Training and certification of competency were mandatory prior to individuals broaching BRCA testing with patients. The learning resources pack for BRCA training consisted of a series of online videos and written material delivered by the genetics team. The material covered the protocol to identify patients; information regarding the relevance of BRCA testing; significance for patients with a normal BRCA result and those with a mutation identified; significance of a BRCA variant requiring evaluation, the implications for family members if a positive result was identified and frequently asked questions. Following completion of the training package, nurses completed a checklist and self-certification of competency to consent patients for BRCA testing. Nurses were also given the opportunity to have face-to-face training and received supervision from the trained oncologists until they felt confident. The testing protocol is shown in Figure 1.

If a patient was identified as eligible for BRCA testing, within the oncology clinics he or she was provided with written information on BRCA testing. Patients were often known by the CNS who acted as their key worker. A discussion between the nurse and the patient would take place and the consent form would be discussed. Patients were able to ask questions at any stage in the process and if the patient or nurse felt it necessary, patients could be referred to the genetics team directly at any point in the testing pathway. Following signing of the consent form by the patient and nurse, a BRCA test request form was completed by the nurse and given to the patient so they could proceed with the blood test.

When patient results became available from the genetics team, within 8 weeks they were entered on the electronic patient record system and sent to the patient’s consultant. Nurses were able to deliver BRCA results where no mutation was identified directly to the patient in the oncology clinic. Following a year of this protocol, based on feedback from team members and patients, results in the form of a letter were sent directly to the patient If a BRCA mutation was identified, in addition to oncologists explaining the relevance for oncological management, patients were automatically sent an appointment with the genetics team for further discussion of hereditary implications, risk and screening for other cancers. There was the opportunity for information to be provided by the genetics team to family members of patients identified to carry a germline BRCA mutation and subsequent BRCA testing

Results

Evaluation of the BRCA testing model

In the gynaecology unit, of the 25 health professionals that underwent BRCA testing training, 4 (16%) were nurses. Analysis of the BRCA consents and request forms indicated that the highest recruiter of patients for BRCA testing was a CNS. Of these 300 patients (the total number of patients during the time period), 108 were counselled and consented by the CNS team, and 192 by doctors. There was no difference in reported patient satisfaction between those consented by a nurse, or a doctor in the first 119 patients offered the questionnaire (George et al, 2014). A total of 75 of the 108 patients consented by nurses completed the questionnaire. A patient survey distributed to the pilot group of patients demonstrated that no patients refused testing, or requested a genetics appointment before testing. All health professionals including nurses felt confident in consenting and giving results to patients, and none reported they were asked questions they were unable to answer after undergoing training.

To further establish the views of the gynaecology CNSs a questionnaire (Box 1) was sent to six nurses. Five nurses completed the questionnaire. It included several specific questions related to the extended role of consenting for BRCA- testing. This included a question specific to nurses who had completed training and consented a patient, and a question specific to nurses who had completed the training but were yet to complete the consent process. All CNSs had completed BRCA-specific consent training. Responses to the questions indicated that all nurses found the BRCA training videos helpful and a good method of learning. All nurses felt that BRCA testing was part of their role. All nurses commented on the importance of patients being offered BRCA testing. One nurse commented on the concerns she had about the BRCA testing being carried out in busy oncology clinics and discussed the anticipation of added time pressures; however those nurses who had performed the majority of the BRCA consents reported no significantly added time in consultations and no added pressures to the clinic. All nurses involved felt well supported to undertake the BRCA consent and were reassured about the option of genetic follow up if required.

Box 1. BRC A consenting nurse questionnaire.

Did you find the BRCA training videos adequate for consenting gynaecology oncology patients in oncology clinics?

Did you feel that BRCA testing was part of your role as a clinical nurse specialist/research nurse?

Do you feel it is important for patients to be offered BRCA testing?

Do you feel it works well for patients to be offered BRCA testing within a standard oncology appointment?

Did you feel comfortable consenting a patient for BRCA testing or did you feel there were more areas for education? (Please only complete this question if you have carried out the consent process)

What barriers have stopped you from carrying out the consent process in clinic (e.g. time, lack of opportunity, knowledge (Please only complete this question if you completed the BRCA training but have not yet consented a patient)

Please provide below any other comments that you have on the BRA consenting process

One nurse felt that a barrier to the consenting process may be lack of time and this was the same nurse who raised concerns about ready busy oncology clinics. General comments on the BRCA consenting process emphasised the importance of CNSs being well placed with in the oncology clinics to offer the testing as the patient advocates.

Nurses were also very aware that discussing BRCA at initial consultations may not be the optimum time for patients, as often there can be an overload of information. However nurses did feel it was their role as the patient advocate to re-visit this at a later appointment, highlighting that nurses felt that this should be part of their responsibility as part of an advanced role

Discussion

The implementation of BRCA testing within the medical oncology clinics is practice-changing. The revised eligibility criterion allows all patients with non-mucinous epithelial ovarian cancer of any age to be offered BRCA testing. Based on the success of the pilot MCG study, this model is the current standard practice at the Royal Marsden. Knowledge of the BRCA mutation status has already helped guide patient management and following the recent licence of Olaparib, will be crucial for patients to access PARP inhibitors.

When the pilot began the criteria were such that some ovarian cancer patients were not eligible for testing. Owing to the demand and the success of the pilot BRCA gene testing, the current practice at the Royal Marsden is for the test to be offered to ovarian cancer patients of any age and with all non- mucinous tumours. This is in line with NICE recommendations that include germline BRCA testing of patients with ovarian cancer that have a combined BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carrier probability of 10% or more (NICE, 2013). This has a significant impact on the patient and also family members. For patients who were found to have a BRCA mutation, treatment options potentially changed as they could have access to clinical trials involving PARP inhibitors. With the continued development of PARP inhibitors and the recent olaparib licence, this additional information is paramount for ovarian cancer patients. For women with a germline BRCA mutation, this also allowed family members to be tested. This has implications for prevention and screening, which would be discussed in the genetics clinics.

The CNSs are ideally placed to deliver information in BRCA testing and consenting. In many cases, patients and their CNS already have an established rapport; ensuring patients are comfortable with the discussions, and feel able to ask questions that they may not otherwise ask.These are also the reasons why the CNS team felt it was a natural expansion to its role and was well placed in the medical oncology clinics It is important to note that the nurses had the option of referring the patient to the genetics department at any time, if they felt that the patient had questions that they could not address; although in practice this has not occurred. Having this backup is vital because it is important for nurses to feel supported when taking on new roles. Nurses also have the advantage of continuity of care with patients, often more so than the frequently changing junior medical team.

As genetic testing becomes a routine part of patient care, it will be important that all members of the team, including the CNS, have a good understanding of the implications of testing for both patients and family members. It is important to point out that CNSs do not discuss BRCA mutations with unaffected family members. Oncology nurses are important advocates to identify patients understanding and concerns during the BRCA testing process. Based on the Royal Marsden experience so far, it is evident that the delivery of BRCA testing in oncology clinics by health professionals including CNSs is feasible and welcomed by patients, oncology and genetics teams. It is critical that nurses are given adequate training and support for this combined oncology-genetics model to be successfully taken up by other cancer centres and benefit the overall quality of cancer care for patients.

Patients are offered BRCA testing at any point in the care pathway. It was identified that this meant that patients under 6 month or annual follow-up may not receive the BRCA test result till their next routine clinic visit in 6 months to a year. Subsequent to the pilot phase, this issue has been addressed; the genetics team automatically send the BRCA result and information on the relevance of the result as soon as available thereby ensuring that patients receive results within 4 weeks, and are offered a genetics appointment if a BRCA mutation is identified.The revised pathway is more streamlined for patients and means that patients get their results in a more timely manner (currently 2–4 weeks at the Royal Marsden), with the aim to reduce any anxiety caused by waiting for results. An appointment with the genetics team is offered within 2–3 weeks of the patient receiving the result. From a nursing perspective this is advantageous as it means that patients have time to think of any questions that they may have for the team or contact the CNS if they are unsure or concerned.

Conclusion and recommendations

Evaluation of this pathway has shown that ovarian cancer patients were happy to receive BRCA testing in oncology appointments. There were no concerns raised about receiving information or consent taking from nurses, and in many cases the existing rapport between the CNS and the patients helped to facilitate discussion about BRCA testing and the consenting process.

Individual trusts may have their own guidelines around general consent. For CNSs to add BRCA testing to their role, general consent training would need to be undertaken in addition to specific BRCA consenting and training. As genetic testing becomes integrated into routine cancer care in ovarian cancer and other malignancies (e.g. breast cancer and pancreatic cancer) this will become an increasingly important aspect of scope of practice and patient care.

Moving forward in practice it will be essential to gain further insight into the patient perceptions of BRCA testing and the experience of adding this additional testing to their cancer pathway.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Royal Marsden/Institute of Cancer Research, National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Specialist Biomedical Research Centre, The Royal Marsden Cancer Charity, the Mainstreaming Cancer Genetics (MCG) Programme and The Wellcome Trust.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: none

References

- Alsop K, Fereday S, Meldrum C, et al. BRCA mutation frequency and patterns of treatment response in BRCA mutation-positive women with ovarian cancer: a report from the Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(21):2654–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.8545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S, Kaye SB, Ashworth A. Making the best of PARP inhibitors in ovarian cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7(9):508–19. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Research UK. Ovarian cancer incidence statistics. [accessed 9 June 2016];2016 http://tinyurl.com/h64w2as.

- Cook O, McIntyre M, Recoche K. Exploration of the role of specialist nurses in the care of women with gynaecological cancer: a systematic review. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(5–6):683–95. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Medicines Agency. EPAR summary for the public. [accessed 13 June 2016];Lynparza olaparib. 2014 http://tinyurl.com/h7dwa9b.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Olaparib. [accessed 9 June 2016];2014 http://tinyurl.com/ zcnqfhk.

- George A, Smith F, Cloke V, et al. Implementation of routine BRCA gene testing of ovarian cancer (OC) patients at Royal Marsden Hospital Poster discussion at European Society for Medical Oncology 2014. [accessed 9 June 2016];2014 doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu338. http://tinyurl.com/h9vy48t [Annals of Oncology (2014) 25 (suppl_4): iv305-iv326. [DOI]

- George A. UK BRCA mutation testing in patients with ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 2015;113(Suppl 1):S17–21. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray A. Advanced or advancing nursing practice: what is the future direction for nursing? Br J Nurs. 2016;25(1):8–13. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2016.25.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong J, Gabler S. Counseling, screening, and therapy for newly-diagnosed HIV patients. Nurse Pract. 2015;40(10):34–44. doi: 10.1097/01.NPR.0000471359.56745.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledermann J, Harter P, Gourley C, et al. Olaparib maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive relapsed serous ovarian cancer: a preplanned retrospective analysis of outcomes by BRCA status in a randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(8):852–61. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70228-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moschetta M, George A, Kaye SB, Banerjee S. BRCA somatic mutations and epigenetic BRCA modifications in serous ovarian cancer. Annals of Oncology. 2016 doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw142. mdw142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Familial breast cancer: classification, care and managing breast cancer and related risks in people with a family history of breast cancer. [accessed 9 June 2016];2013 http://tinyurl.com/js37mmu. [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Olaparib for maintenance treatment of relapsed, platinum-sensitive, BRCA mutation-positive ovarian, fallopian tube and peritoneal cancer after response to second-line or subsequent platinum-based chemotherapy. [accessed 9 June 2016];2016 http://tinyurl.com/jcb4wrq.

- Rahman N. Mainstreaming genetic testing of cancer predisposition genes. Clin Med. 2014;14(4):436–9. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.14-4-436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade I, Riddell D, Turnbull C, Hanson H, Rahman N. Development of cancer genetic services in the UK: A national consultation. Genome Med. 2015;7(1) doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0128-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]