Abstract

Coproheme decarboxylases (ChdCs) are enzymes responsible for the catalysis of the terminal step in the coproporphyrin-dependent heme biosynthesis pathway. Phylogenetic analyses confirm that the gene encoding for ChdCs is widespread throughout the bacterial world. It is found in monoderm bacteria (Firmicutes, Actinobacteria), diderm bacteria (e. g. Nitrospirae) and also in Archaea. In order to test phylogenetic prediction ChdC representatives from all clades were expressed and examined for their coproheme decarboxylase activity. Based on available biochemical data and phylogenetic analyses a sequence motif (-Y-P-M/F-X-K/R-) is defined for ChdCs. We show for the first time that in diderm bacteria an active coproheme decarboxylase is present and that the archaeal ChdC homolog from Sulfolobus solfataricus is inactive and its physiological role remains elusive. This shows the limitation of phylogenetic prediction of an enzymatic activity, since the identified sequence motif is equally conserved across all previously defined clades.

Keywords: Coproheme decarboxylase, Phylogeny, Heme biosynthesis, Archaea, Nitrospirae

1. Introduction

In recent years our knowledge about prokaryotic heme biosynthesis expanded rapidly by the discovery of the coproporphyrin-dependent heme biosynthesis pathway [1]. This development was sparked by the identification of the enzyme coproheme decarboxylase (ChdC, formerly referred to as HemQ), which catalyzes the hydrogen peroxide triggered cleavage of two CO2 molecules from iron coproporphyrin III (coproheme) propionates at positions 2 and 4 to form vinyl groups and yielding heme b as final product [2–5].

Coproheme decarboxylases were first mentioned in literature as chlorite dismutase-like proteins (Cld-like), as they popped up in large numbers during phylogenetic analyses of chlorite dismutase sequences [6–10]. While chlorite dismutases are defined by a catalytic arginine [7,11,12], which is located on the distal heme side, ChdCs are lacking this catalytic arginine (glutamine, alanine, leucine, isoleucine or serine are present at the respective position) and are therefore inactive towards chlorite. ChdCs are also missing an H-bonding network anchoring the proximal histidine, which governs the integrity of the heme. Its lack is a necessity for ChdCs to release heme b [13,14]. All ChdCs share the same overall two-domain ferredoxin-like fold also found in Clade I chlorite dismutases. This includes a potential heme/coproheme binding site.

Later, biochemical studies showed that coproheme decarboxylases are involved in heme biosynthesis, either as an active enzyme or as a regulatory protein [2,14,15]. Finally, the protoporphyrin-dependent heme biosynthesis pathway (formerly known as “classical” prokaryotic heme biosynthesis pathway) proved to be an insufficient model for most monoderm bacteria (Scheme 1), since they are lacking the gene for coproporphyrin decarboxylase (CgdC, formerly HemF) or coproporphyrin dehydrogenase (CgdH, formerly HemN) [1], but possess a ChdC (HemQ) gene. The definition of the coproporphyrin-dependent pathway by Dailey and co-workers was a major breakthrough for understanding prokaryotic heme biosynthesis (Scheme 1) [1]. In the recent excellent review on bacterial heme biosynthesis [16], it is suggested, based on phylogenetic studies that the coproporphyrin-dependent pathway is mainly utilized by monoderm bacteria, but not exclusively. A third important alternative heme biosynthesis pathway is utilized by Archaea and denitrifying bacteria, where heme b is synthesized via siroheme (Scheme 1).

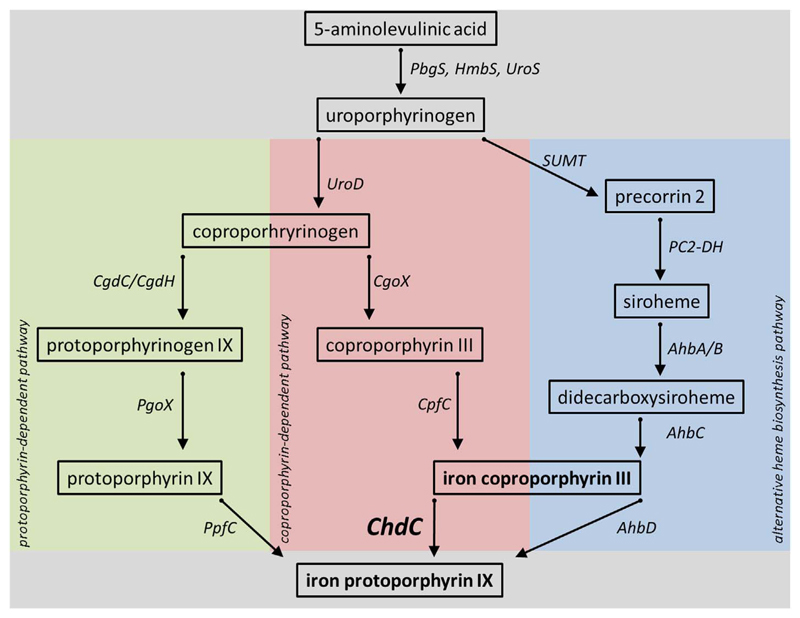

Scheme 1. Heme biosynthetic pathways.

Schematic representation of the protoporphyrin-dependent pathway (left panel, green), the coproporphyrin dependent pathway (center panel, red), and the alternative heme biosynthesis pathway (right panel, blue). The common core is shown in grey. PbgS, porphobilinogen synthase; HmbS, hydroxymethylbilane synthase; UroS, Uroporphyrinogen III synthase; UroD, Uroporphyrinogen III decarboxylase; CgdC, coproporphyrinogen decarboxylase; CgdH, coproporphyrinogen dehydrogenase; PgoX, protoporphyrinogen oxidase; PpfC, protoporphyrin ferrochelatase; CgoX, coproporphyrinogen oxidase; CpfC, coproporphyrin ferrochelatase; ChdC, coproheme decarboxylase; SUMT, S-adenosyl-l-methionine-dependent uroporphyrinogen III methyltransferase; PC2-DH, precorrin2 dehydrogenase; AhbA/B/C/D, alternative heme biosynthesis proteins A/B/C/D.

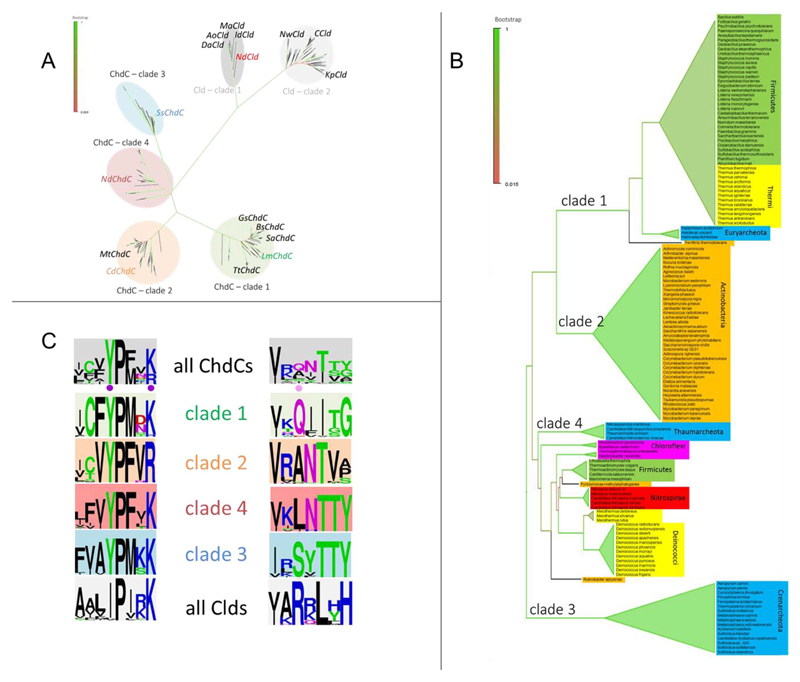

Phylogenetic analyses provide invaluable information on the universality of ChdCs, but biochemical data of this structural superfamily are only available for both clades of chlorite dismutases and for two out of four clades of ChdCs (Fig. 1A). We now present in an updated phylogeny of the structural family of ChdCs (Fig. 1) that also some diderm (e.g. Nitrospirae) and intermediate (Deinococci - Thermi) representatives carry ChdC genes. Furthermore, ChdC genes are also present in various Archaea; with Crenarcheota forming their own phylogenetic outgroup (Clade 3, Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1. Phylogeny of ChdCs and Clds.

(A) Phylogenetic overview of sequences of the CDE structural superfamily. The Maximum-Likelihood phylogenetic tree is represented in the radial tree layout, representatives that were studied on a protein level are written out in black; targets of this study are colored. (B) Rectangular tree layout of the ML-tree of ChdC sequences analyzed within this study. (C) Sequence alignments and fingerprints represented as WebLogos of all sequences present in the phylogenetic analysis. Positions of the catalytic residues for ChdCs are indicated with a purple point and the position of the catalytic Cld residue with a pink dot. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Further, we define a sequence motif for ChdC and provide biochemical data for all phylogenetic clades from ChdCs, in order to verify the predicted phylogeny and rationalize structure - function relationships. We could show that ChdCs from the monoderm Firmicutes Listeria monocytogenes (Clade 1), the monoderm Actinobacterium Corynebacterium diphteriae (Clade 2), and the diderm nitrite-oxidizing bacterium Nitrospira defluvii (Clade 4) have coproheme decarboxylase activity, whereas the archeon Sulfolobus solfataricus (Clade 3) did not show any activity.

2. Experimental procedures

2.1. Sequence-based computational studies

A selection of 197 ChdC and Cld sequences (Table S1) was collected from public databases (Uniprot, NCBI). First, multiple sequence alignments for ChdCs and Clds were constructed using MUSCLE [17] with following parameters: gap penalties −2.9 and gap extension 0; hydrophobicity multiplier 1.2; max iterations 8. From these sequence alignments a phylogenetic tree was reconstructed for all sequences and separately for ChdC and Cld sequences with the Maximum likelihood algorithm using the Jones-Taylor-Thornton (JTT) model, the γ parameter set to 3, and with 1000 bootstrap replications; complete deletion was used for gaps/missing data treatment. All tools for sequence alignments and phylogentic tree reconstruction were embedded in the MEGA5 package [18]. The trees were drawn with FigTree v1.4 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/). Sequence motifs were generated using WebLogo (http://weblogo.berkeley.edu/) [19]. Information about the heme biosynthesis pathways and annotated genes of the respective organisms was derived from the KEGG database (http://www.kegg.jp/) [20]. Structural models of CdChdC, NdChdC and SsChdC were calculated using I-TASSER (https://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/I-TASSER/) [21].

2.2. Substrate channel calculation

CAVER [22] was used to detect putative channels to the coproheme/heme b binding site of LmChdC (pdb-code: 5LOQ), NdCld (pdb-code: 3NN1) and I-TASSER models of CdChdC, NdChdC and SsChdC. For calculation of the characteristics of the channels, the coproheme iron of LmChdC (5LOQ) or the heme iron of NdCld (3NN1) was set as a starting point for both proteins, which were structurally aligned. Channels were calculated with the following settings: minimum probe radius: 0.9 Å; shell depth: 10 Å; shell radius: 9 Å; clustering threshold: 3.5; number of approximating balls: 12; input atoms: 20 amino acids (without other components present in the respective structural model).

2.3. Protein production

Cloning, expression and purification of LmChdC (lmO2113) was described previously [14], also the protocols for NdCld are already reported [23].

The plasmid for CdChdC (DIP1394) was synthesized and subcloned into a pD441-NH vector (ATUM, Newark, California), containing an N-terminal His-tag. Recombinant CdChdC was expressed in E. coli Tuner (DE3) (Merck/Novagen, Darmstadt, Germany) cells in LB medium (100 μg mL−1 Kanamycin A). 500 mL LB medium were inoculated with 1 mL of a freshly prepared overnight culture. The culture was grown at 37 °C and 180 rpm agitation until the early stationary phase was reached (OD600 = 0.6). In order to induce CdChdC expression, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to a final concentration of 0.5 mM. Prior to induction the temperature was lowered to 16 °C and the cells were further cultivated overnight. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4 °C and 2700 × g for 10 min. The pellet was suspended in approximately 40 mL lysis buffer (20 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 5% glycerol, 0.5% Triton X-100) and cells were lysed by pulsed sonication (Vibra Cell, Sonics & Materials Inc., Danbury, CT, USA; 50% power) 3 times for 60 s. Afterwards the suspension was centrifuged for 25 min at 38720 × g and 4 °C. The supernatant was then filtered (0.45 μm pore size) and loaded on a HisTrap FF column (5 mL, GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 38.5 mM NiCl2. After loading, the column was washed with at least 5 column volumes of binding buffer (500 mM NaCl, 20 mM phosphate - buffer pH 7.0, 20 mM imidazole). Elution was performed using a gradient (100% elution buffer after 60 min at a flow rate of 1 mL min−1) composed of a binding buffer (500 mM NaCl, 20 mM phosphate - buffer pH 7, 20 mM imidazole) and elution buffer (as binding but with 500 mM imidazole).

For further purification size exclusion chromatography (SEC) was performed. The column (HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 pg, GE healthcare) had a particle size of 34 μm and was equilibrated with 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0 plus 100 mM sodium chloride. Finally the collected fractions were pooled and concentrated using a centrifugal filter (Amicon Ultra-15, Merck Millipore Ltd. Tullagreen, Carrigtwohill Co. Cork Ireland, cut-off 100 kDa, centrifuged at 4000 × g and 4 °C for 10 min). The concentrated solution was aliquoted and frozen at −80 °C.

The gene for SsChdC (SsoI 2898) was PCR-amplified from genomic DNA (kindly provided by Christa Schleper) and was subcloned in a modified pET-21b (+) vector for the production of an N-terminal TEV-cleavable Strep-II tagged fusion protein. Expression in E.coli Tuner (DE3) and purification conditions were identical to the ones used for LmChdC [14].

The gene for NdChdC (NIDE 3081) was amplified from genomic DNA (kindly provided by Holger Daims) by PCR and was subcloned via Gibson assembly [24] into a PGEX 6P1 plasmid, which contains an N-terminal PreScission-cleaveable GST-tag. Recombinant NdChdC was expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) pLysS (Merck/Novagen, Darmstadt, Germany) cells in LB medium (100 μg mL−1 Ampicillin, 100 μg mL−1 Chloramphenicol). 500 mL LB medium were inoculated with 1 mL of a freshly prepared overnight culture. The culture was grown at 37 °C and 180 rpm agitation until OD600 = 0.6 was reached. Cells were induced with 0.5 mM IPTG. Prior to induction the temperature was lowered to 16 °C and the culture were further cultivated overnight. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4 °C and 2700 × g for 10 min. The pellet was suspended in approximately 40 mL lysis buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.3, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100) and cells were lysed by pulsed sonication (Vibra Cell, Sonics & Materials Inc., Danbury, CT, USA; 50% power) 3 times for 60 s. Afterwards the suspension was centrifuged for 25 min at 38720 × g and 4 °C. The supernatant was then filtered (0.45 μm pore size) and loaded on a Glutathione Sepharose 4B column (5 mL, GE Healthcare) equilibrated with binding buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.3, 150 mM NaCl). After loading, the column was thoroughly washed with at least 5 column volumes binding buffer. GST-tagged PreScission protease was dissolved in binding buffer and applied with a syringe onto the column for overnight cleavage at 4 °C. NdChdC was eluted with binding buffer from the column with a syringe and further purified using size exclusion chromatography as was described above for CdChdC.

All ChdCs and also NdCld were expressed as apo-proteins and reconstituted with Fe(III) coproporphyrin III chloride (coproheme; Frontiers, Scientific, Logan, UT, USA) as described previously [5].

2.4. Coproheme decarboxylase activity

Time traces at 375 nm of 2 μM coproheme-ChdCs upon reaction with 50 μM H2O2 were recorded on a Hitachi U-3900 spectro-photometer for direct comparison of enzymatic activity at identical conditions (50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0). Titrations of 10 μM ChdCs reconstituted with 5 μM coproheme, starting with sub-equimolar (1 μM) concentrations of H2O2 were monitored on the Hitachi U-3900 spectrophotometer between 700 and 250 nm at room temperature in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0. Coproheme decarboxylase activity for SsChdC was also tested from pH 2–7 and from 25 to 80 °C. At least a 15 min interval was set between each peroxide addition (always 1 μM H2O2 steps) to ensure complete reaction. The titrations were performed in a stirred cuvette at room temperature. 10 μL of the samples with 0 μM, 5 μM and 10 μM H2O2 were taken from the reaction mixture and analyzed by mass spectrometry.

For mass spectrometric analysis, 5 μL of each sample were analyzed using a Dionex Ultimate 3000 system directly linked to a QTOF mass spectrometer (maXis 4G ETD, Bruker) equipped with the standard ESI source. MS scans were recorded in the positive ion mode within a range from 300 to 3750 m/z and the instrument was tuned to detect both the rather small free heme derivatives and intact proteins in a single run. Instrument calibration was performed using ESI calibration mixture (Agilent). For separation of the analytes a Thermo ProSwift™ RP-4H Analytical separation column (250 × 0.2 mm) was used. A gradient from 99% solvent A and 1% solvent B (solvent A: 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid, B: 80% acetonitrile and 20% solvent A) to 65% B in 11 min was applied, followed by a 2 min gradient from 65% B to 95% B, at a flow rate of 8 μL min−1 and at 65 °C. A blank run (5 μL H2O) was performed after each sample to minimize carry-over effects.

2.5. Binding of coproheme

Time-resolved binding of coproheme to apo-ChdCs from all four clades and apo-NdCld was monitored using a stopped-flow apparatus equipped with a diode array detector (model SX-18MV, Applied Photophysics), in the conventional mode. The optical quartz cell with a path length of 10 mm had a volume of 20 μL. The fastest mixing time was 0.68 ms. All measurements were performed at 25 °C. The concentration of coproheme in the cell was 0.5 μM and ChdCs were present in excess (3 μM), to ensure pure spectral species of the coproheme bound proteins. Experiments were carried out in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0. Reactions were simulated and rates were estimated using Pro-Kineticists software (Applied Photophysics) according to the model a (coproheme) + b (apo-protein, set colourless) > c (intermediate species), c > d (coproheme-bound protein).

2.6. Catalase, peroxidase and chlorite dismutase activity

Catalase activity of heme b-SsChdC was tested on a Clark-type electrode (Hansatech Instruments) to monitor oxygen evolution upon addition of H2O2. Substrate concentrations varied between 0.5 and 90 mM, the enzyme concentration was 200 nM. Reactions were carried out in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, and at 30 °C in a stirred sample chamber. Peroxidase activity towards the model substrate ABTS was tested in 50 mM phosphate citrate, phosphate, or glycin/NaOH buffers between pH 4 and 10 at 30 °C using a Hitachi U-3900 spectro-photometer with a stirred quartz cuvette. The enzyme concentration was 1 μM. ABTS concentrations were varied between 5 and 500 μM, and H2O2 concentrations were from 100 to 500 μM. Chlorite dismutase activity was tested at 30 °C using a Clark-type electrode (Hansatech Instruments) at pH 7.0 (50 mM phosphate buffer). The enzyme concentration was 200 nM and the chlorite concentration was varied between 10 mM and 1 mM.

3. Results

Phylogeny

The discovery of ChdCs was initiated by phylogenetic analyses, from which, based on biochemical data of a few representatives, a functional motif could be identified. Here, we report an update of the phylogeny using 197 sequences, formerly classified into the CDE structural superfamily (pfam06778) [9] or peroxidase-chlorite dismutase superfamily [10]. All these sequences represent α, β-domain proteins [25]. Fig. 1A shows a dendogram that clearly separates chlorite dismutases (Clds) and coproheme decarboxylases (ChdCs) in a similar way as previously published [6,7]. In contrast to a previous analysis [10], clade 3 (Crenarcheota) of the ChdC branches forms an outgroup (Fig. 1B). Nevertheless, analyses of the multiple sequence alignment of ChdCs provide a clear motif that was found to be unique for ChdCs (Fig. 1C). As was published by the group of DuBois, ChdCs rely on a catalytic tyrosine (Y145 in ChdC from Staphylococcus aureus) and a catalytically important lysine (K149 in SaChdC) [26]. The tyrosine is completely conserved in all ChdCs while it is predominantly an isoleucine in Clds. The catalytic tyrosine is followed by an equally conserved proline. The positively charged lysine is conserved throughout all analyzed sequences, with the exception of clade 2 ChdCs, where a positively charged arginine can be found at the respective position (Fig. 1C). Instead of the catalytic arginine of chlorite dismutase [7,11] several other resiudes are conserved in the same region and were found to be unique to each clade of ChdCs; glutamine for clade 1, alanine for clade 2, serine for clade 3 and leucine for clade 4 (Fig. 1C).

Genes involved in heme biosynthesis

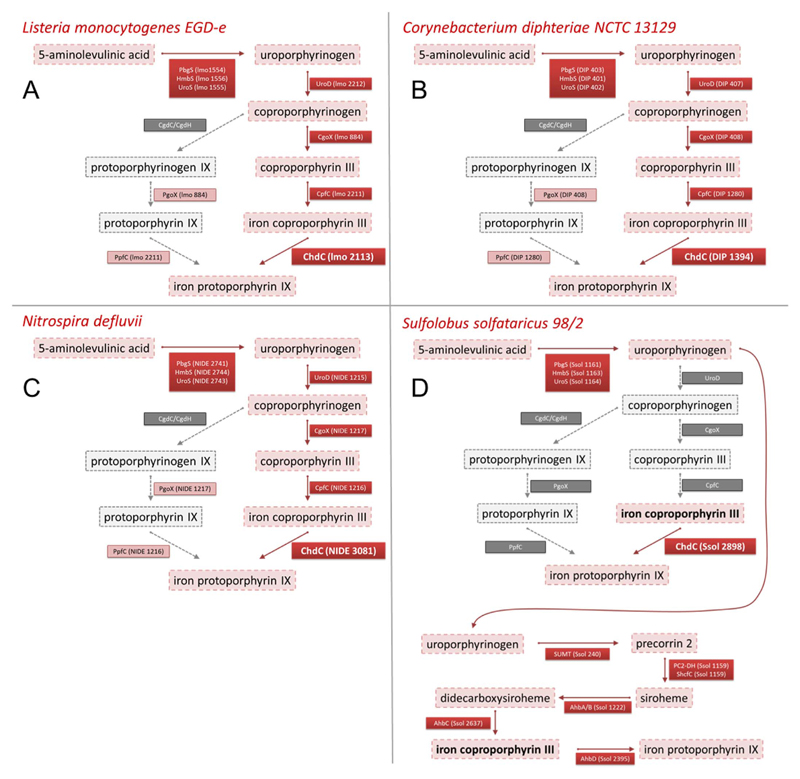

Using the KEGG database, an overview of the annotated genes within the heme biosynthesis machineries of the four organisms present in this study was prepared (Fig. 2). All four organisms are lacking a coproporphyrinogen decarboxylase or dehydrogenase (CgdC/CgdH). Thus they are unable to synthesize heme b via the protoporphyrin-dependent pathway (formerly known as “classic” prokaryotic heme biosynthesis pathway). L. monocytogenes, C. diphteriae and N. defluvii possess all genes necessary to produce heme b via the coproporphyrin-dependent pathway [1], which makes a strong case that the annotated ChdC genes are actually functional (Fig. 2A–C). S. solfataricus on the other hand is lacking all genes of the protoporphyrin- and the coproporphyrin-depentend pathway except a predicted coproheme decarboxylase. It is however equipped with the complete machinery for the anaerobic alternative heme biosynthesis (Ahb) pathway that utilizes siroheme, which is commonly found in Archaea [27] (Fig. 2D). Interestingly, in both the Ahb pathway and the coproporphyrin-dependent pathway iron coproporphyrin III is the substrate for the ultimate reaction. In the Ahb pathway this step is catalyzed by alternative heme biosynthesis decarboxylase (AhbD), an enzyme predicted to work analogous to CgdC [28]. It belongs to the radical SAM family and is also present in S. solfataricus.

Fig. 2. Heme biosynthesis pathways.

Schematic overview of heme biosynthesis intermediates and enzymes according to the protoporphyrin-dependent pathway (left lane after coproporphyrinogen) and coproporphyrinogen-dependent pathway (right lane) for (A) Listeria monocytogenes, (B) Corynebacterium diphteriae, (C) Nitrospira defluvii, and (D) Sulfolobus solfataricus, where the alternative heme biosynthesis pathway is added. Genes present for the respective catalytic reactions are in red boxes and genes not annotated in the genome are in grey boxes, consequently proposed reaction intermediates are in red boxes (with dashed frame) or in grey boxes (with dashed frame), when they do not occur. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

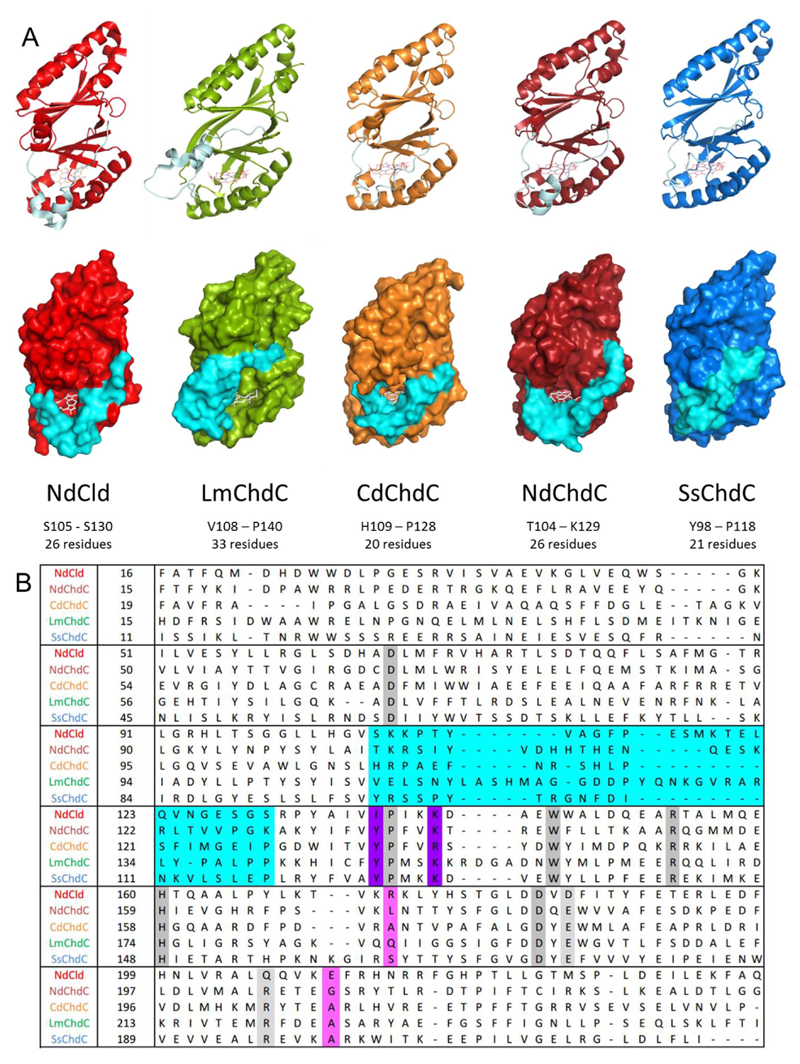

Structures

As mentioned, coproheme decarboxylases and chlorite dismutases share an overall ferredoxin-like fold. All ChdCs and clade I Clds are homopentamers and have a subunit size of 250–300 amino acids that form an N-terminal and a C-terminal ferredoxin-like fold. Only the C-terminal domain has a functional coproheme/heme b binding site. Dimeric clade II Clds are N-terminally truncated and also show one heme b binding site. In this study, five different members from different clades (all homopentamers) of the structural superfamily are biochemically compared. We examined secondary structural elements based on crystal structures for NdCld (pdb-code: 3NN1) and LmChdC (pdb-code: 5LOQ) and I-TASSER models from NdChdC, CdChdC and SsChdC (Fig. 3). While most β-sheets, α-helices and loops overlay nicely one loop differs between the five proteins. This loop (in cyan in Fig. 3A) defines the putative substrate access channel (for coproheme or heme b, and hydrogen peroxide or chlorite, respectively). The sequence alignment in Fig. 3B shows that in LmChdC the loop is the longest. In crystal structures of LmChdC (pdb-codes: 4WWS, 5LOQ) this loop was only resolved in two out of five subunits, where it was stabilized through crystal contacts with adjacent molecules [5,14]. Therefore it can be assumed that it is highly flexible. Incidentally, this loop forms the top of the putative substrate access channel in LmChdC, while it forms its bottom in NdCld, and the I-TASSER models of CdChdC and NdChdC. In SsChdC the loop covers nearly the entire entrance channel. This was further examined by calculations using CAVER, showing that the substrate entrance channel predicted for SsChdC has the smallest bottleneck radius (1 Å) and that NdCld and LmChdC have the largest bottleneck radii with around 2.5 Å (Fig. S1).

Fig. 3. Structural overview of ChdCs and NdCld.

(A) Secondary structures of NdCld (red), LmChdC (green), CdChdC (orange), NdChdC (dark red), and SsChdC (blue) represented as cartoon (top) and surface representation (bottom). The substrate channel defining loop is depicted in cyan. (B) Sequence alignment of the five investigated proteins, conserved residues are marked in grey, ChdC relevant residues in purple, Cld relevant in pink; the loop defining the substrate channel is represented in cyan as in the structural overview. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Coproheme binding

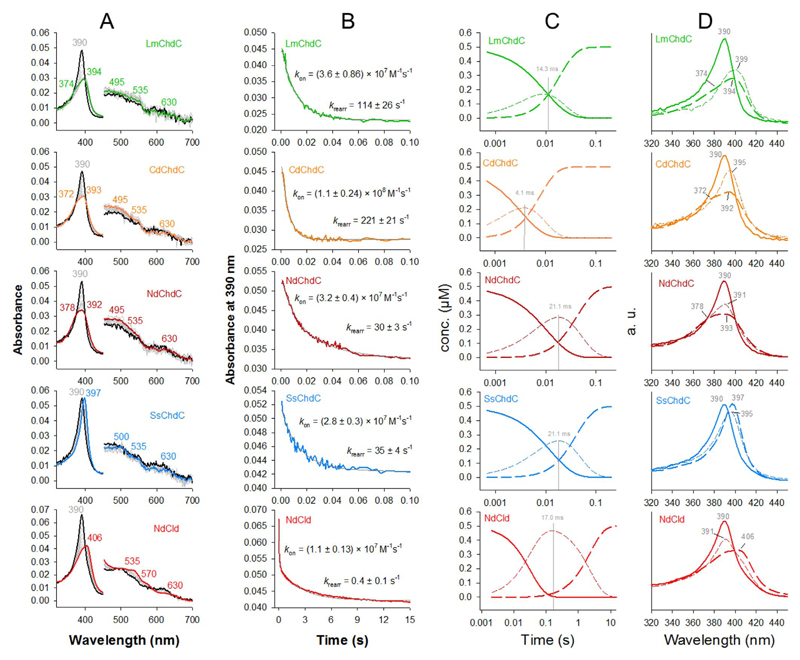

Binding of coproheme is the precondition for any coproheme decarboxylase activity. We estimated the binding kinetics of coproheme comparatively for ChdCs from all four clades (LmChdC, CdChdC, NdChdC, SsChdC) and NdCld using stopped-flow spectroscopy under the exact same conditions. Coproheme binding to LmChdC and SaChdC (both ChdCs from Firmicutes) was reported previously to be biphasic and was found be similar for the two investigated enzymes [29]. The biphasic behavior of coproheme binding was previously explained by two consecutive events: (i) initial rapid binding of the prosthetic group by the proximal histidine followed by (ii) a slower rearrangement of the α-helix harbouring the proximal histidine and establishment of noncovalent interactions between the prosthetic group and the protein [29]. In Fig. 4 spectral changes upon coproheme binding and time traces at 390 nm are reported as well as simulated data using Pro-K software, to identify intermediate species and concentration profiles. The initial binding of coproheme to all five tested proteins is very fast with estimated rates in the following hierarchy: CdChdC (kon = 1.1 × 108 M−1 s−1) > LmChdC (kon = 3.6 × 107 M−1 s−1) > NdChdC (kon = 3.2 × 107 M−1 s−1) > SsChdC (kon = 2.8 × 107 M−1 s−1) > NdCld (kon = 1.1 × 107 M−1 s−1). After 0.1 s coproheme binding to ChdCs is completed, whereas in NdCld the entire process takes up to 15 s or more. This is reflected in the estimated rates of the rearrangement phase, which follows almost the same hierarchy: CdChdC (krearr = 221 s−1) > LmChdC (krearr = 114 s−1) > SsChdC (krearr = 35 s−1) > NdChdC (krearr = 30 s−1) > NdCld (krearr = 0.4 s−1). The biphasic behavior is represented by the intermediate species and the concentration profiles (short dashed lines, Fig. 4C & D) in the simulated spectra.

Fig. 4. Coproheme binding.

(A) Experimental spectra of coproheme (black lines) binding to LmChdC (top, green), CdChdC (orange), NdChdC (dark red), SsChdC (blue), and NdCld (bottom, red). Intermediate spectra are shown in grey. (B) Time traces at 390 nm for all five proteins (in the respective color) with double exponential fits (shown in grey). (C) Concentration profiles over time obtained from simulations of the spectra using Pro-K software. Solid lines (in the respective colors) represent the concentrations of free coproheme, short dashed lines show the concentration of the calculated intermediate, long dashed lines show the concentration of the coproheme-bound protein in their final states. (D) Calculated spectra of free coproheme (solid lines), coproheme-protein intermediate species (short dashed lines) and coproheme-bound ChdCs (long dashed lines). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

The final spectra of coproheme-bound ChdCs vary significantly. While LmChdC and CdChdC show Soret maxima at 394 and 393 nm with shoulders at 374 and 372 nm, respectively, this shoulder is redshifted to 378 nm in NdChdC, while the Soret maximum is at 392 nm. Coproheme-bound LmChdC, CdChdC and NdChdC have extinction coefficients at the Soret maxima of 68000 M−1 cm−1 [29], whereas coproheme-bound SsChdC has a very sharp Soret band with a maximum at 397 nm and an extinction coefficient identical to that of free coproheme of 128800 M−1 cm−1 [29]. Coproheme-bound NdCld has an extinction coefficient at the Soret maximum at 406 nm of 90700 M−1 cm−1. Coproheme-bound NdCld is the only protein that has characteristic bands of a 6-coordinated low-spin species (Q-bands at 535, 570 nm) and only a small charge transfer band at 630 nm, indicating a mixed population of high-spin and 6-coordinated low-spin coproheme. All ChdCs have bands in the visible region which are indicative of high-spin heme (Fig. 4).

Coproheme decarboxylase activity

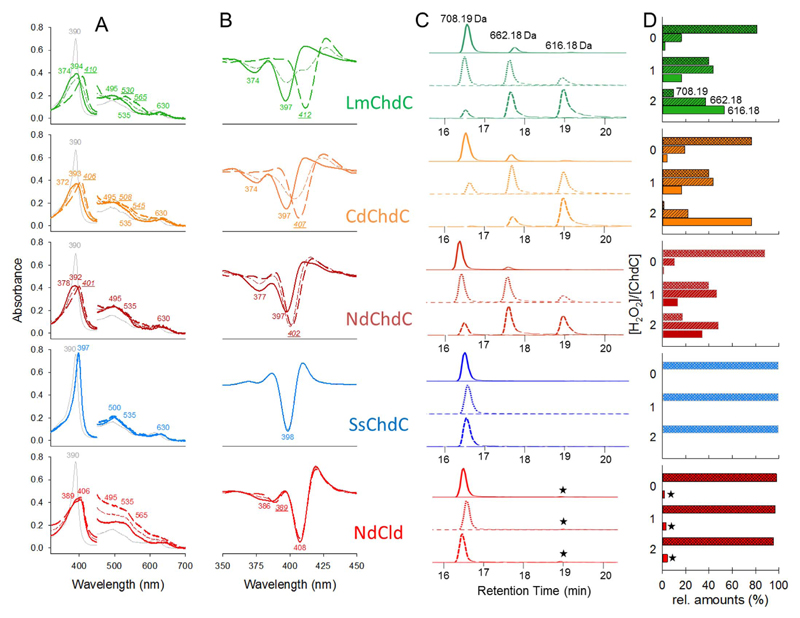

Coproheme decarboxylase activity follows two consecutive decarboxylation steps that oxidatively decarboxylate coproheme into heme b by an excess of hydrogen peroxide or peroxyacetic acid. All five coproheme-bound proteins in this study were titrated with hydrogen peroxide to test their activity. Titrations were followed using UV–vis spectroscopy and mass spectrometry (Fig. 5). Activity for LmChdC was already reported [5] and was confirmed in the measurements here. High-spin coproheme LmChdC is converted into a low-spin heme b species with a Soret maximum of 410 (412 in the second derivative) and Q-bands at 530 and 565 nm. Mass spectrometric data shows that three of the four enzymes (LmChdC, CdChdC, NdChdC) start to convert coproheme to the three propionate intermediate (monovinyl, monopropionate deuteroheme) even without the addition of hydrogen peroxide (Fig. 5C & D). This is most probably due to oxygen activation and subsequently hydrogen peroxide formation. At a two-fold excess of hydrogen peroxide almost all coproheme is converted into heme b. There is still a reasonable amount of three-propionate intermediate present (Fig. 5C & D), as conversion efficiency depends on the number of titration steps (smaller steps lead to more efficient conversion). CdChdC converts coproheme most efficiently into heme b. Upon addition of hydrogen peroxide CdChdC forms a high-spin heme b-CdChdC complex (Soret maximum at 406 nm, 407 in the second derivative, Q-bands at 508 and 545 nm) (Fig. 5). NdChdC is also an active coproheme decarboxylase, as it qualitatively forms heme b. However, it is prone to heme bleaching. In contrast to CdChdC and LmChdC a pure spectral heme b species cannot be detected under these conditions. Interestingly, SsChdC does not show any activity upon titration with hydrogen peroxide. Mass spectrometric analysis identified coproheme as sole component in all samples. This shows that coproheme conversion is neither achieved through oxygen activation nor through the addition of hydrogen peroxide (Fig. 5). Since S. solfataricus is an extreme acido-thermophile we also performed hydrogen peroxide titrations at conditions from pH 2 to pH 7 and from 20 to 80 °C, but no coproheme conversion was detected (data not shown). Coproheme-bound NdCld was used as a negative control, since it is lacking the predicted catalytic tyrosine (Figs. 1C and 3B), which is necessary to convert coproheme to heme b. In fact no conversion could be detected. The mass spectrometrically detectable residual heme b fraction (Fig. 5C and D) may result from heme b incorporation in the apoprotein during expression in E.coli. Coproheme-bound NdCld started to precipitate upon addition of hydrogen peroxide (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5. Coproheme decarboxylase activity.

H2O2 titrations of LmChdC (green), CdChdC (orange), NdChdC (dark red), SsChdC (blue) and NdCld (red) followed by (A) UV–vis absorption spectroscopy, (B) their second derivatives, and (C) mass spectrometry; samples measured without addition of H2O2 are shown as solid lines, at equimolar H2O2 as short dashed lines and at a twofold excess of H2O2 as long dashed lines. Wavelengths for spectra represented in long dashed lines are shown in italic and underlined, whereas wavelengths for the initial spectrum (solid) lines are depicted upright. (D) Relative amounts of coproheme (two-way striped bars), monovinyl, monopropionate deuteroheme (striped bars), and heme b (no pattern) at different H2O2 to protein ratios. The asterisk indicates heme b present in apo-NdCld from expression in E. coli. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Time dependent conversion of coproheme was monitored spectroscopically at 375 nm for all five coproheme-bound proteins. Initial velocities are compared under identical conditions (50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, 25-fold excess of H2O2). Due to heme bleaching, caused by high excess of H2O2, steady-state kinetic parameters could not be determined reliably. Nevertheless the initial velocities after addition of 50 μM H2O2 result in the following hierarchy: conversion of 2 μM coproheme is catalyzed most efficiently by CdChdC (v0 = 4.8 μM s−1), followed by NdChdC (v0 = 2.6 μM s−1), LmChdC (v0 = 0.1 μM s−1) and SsChdC, which does not convert any coproheme (Fig. S2). NdCld does not show any decarboxylation activity, as mentioned above, and suffers from protein instability (precipitation) upon addition of hydrogen peroxide.

Catalase and peroxidase activity of SsChdC

Because no coproheme decarboxylase activity was detected for SsChdC, the protein was also reconstituted with hemin to form the heme b-bound SsChdC (Fig. S3A). Catalase activity was tested with a clark-type electrode, to monitor oxygen generation, but no significant activity could be detected (Fig. S3B). Likewise no peroxidase activity towards H2O2 and ABTS could be detected nor any chlorite dismutase activity (ClO2 → O2 and Cl−) (data not shown).

4. Discussion

Sequence based computational methods were the basis for discovery and identification of the coproporphyrin-dependent heme biosynthesis pathway that was first described in 2015 by Dailey and co-workers [1]. Even before the discovery of the biological activity of ChdCs, phylogenetic analyses of these sequences (formerly referred to as “chlorite dismutase-like” or HemQ proteins) clearly indicated a certain importance for the respective organisms, since they are highly abundant and wide-spread [6–8]. A knockout of ChdC in S. aureus exhibit a small colony phenotype [15]. A knockout of ChdC in L. monocytogenes was not viable, and therefore was considered essential [30]. Until now only a few representatives of ChdCs were studied on a protein level, in Fig. 1A these proteins are written in black. Thorough spectroscopic and structural studies were performed on representatives from clade 1 ChdCs (Firmicutes) [4,5,26,29,31]. The lack of biochemical data on representatives from Clade 3 and 4 prompted us to express and purify representatives from all ChdC clades and to test the phylogenetic prediction on a biochemical level.

From sequence alignments and phylogenetic analyses we identified a ChdC specific sequence motif -Y-P-M/F-X-K/R- (Fig. 1C), which suggests that all ChdC clades should be active towards coproheme and hydrogen peroxide. This would empower them to be part of the coproporphyrin-dependent heme biosynthesis pathway.

When looking at the genes present for the just mentioned pathway (Fig. 2), first doubts arise about the role of ChdC in S. solfataricus. While L. monocytogenes, C. diphteriae and N. defluvii all have the complete set of genes necessary for the coproporphyrin-dependent pathway, S. solfataricus is lacking all of them and only carries a gene for a potential ChdC (SsO2898). Furthermore, the Archeon is equipped with the complete anaerobic alternative heme biosynthesis pathway, including AhbD, which catalyzes the same reaction as ChdC (Fig. 2) [27]. Dailey and Gerdes note in a review from 2015 that a definite assignment of archaeal ChdC homologs as participants in heme biosynthesis requires characterization of these individual enzymes on a protein level [32].

In this work representatives from all ChdC clades were expressed, purified, biochemically characterized and further compared with coproheme-reconstituted NdCld, as a negative control for ChdC activity. While all potential ChdCs bind coproheme to form high-spin complexes, NdCld forms a low-spin coproheme complex (Fig. 4), most probably caused by the distal arginine, which is the catalytic residue for chlorite dismutase activity in the heme b enzyme.

Interestingly, coproheme-ChdC from S. solfataricus has a UV–vis spectral fingerprint that differs significantly in the Soret region to the UV–vis spectral features of coproheme-LmChdC, -CdChdC and -NdChdC (Figs. 4 and 5). In SsChdC the Soret band is very sharp and has an extinction coefficient twice as high as LmChdC, CdChdC and NdChdC. We could not detect any coproheme decarboxylation activity under the comparative conditions used for all proteins. Taking the habituate of S. solfataricus into account, we decided to test further conditions. S. solfotaricus is a thermoacidophilic Archeon that grows between 55 and 90 °C and at a pH optimum between 2 and 3. The cytoplasmic pH is maintained at 6.5; it requires an aerobic environment [33,34]. However, no reactivity towards coproheme was detected between pH 2 and 7, and from 25 up to 80 °C. It is not completely understood how this Archeon deals with H2O2, as there is no catalase annotated [35]. It is likely to form a novel supramolecular complex for mitigating oxidative damage including a peroxiredoxin and a DPS-like protein [36]. In order to exclude a role in oxidative stress mitigation SsChdC was reconstituted with heme b and tested for catalase, peroxidase and chlorite dismutase activity. However, SsChdC reconstituted with heme b did not show any significant catalase, peroxidase or chlorite dismutase activity. For now, the actual role of this protein remains elusive and needs to be further investigated; therefore the protein cannot be classified as ChdC, even though the sequence motif would suggest a coproheme decarboxylase function.

All investigated representatives from the other clades showed coproheme decarboxylase activity (Fig. 5). Until now coproheme decarboxylase activity was only shown experimentally for representatives from clade 1 (Firmicutes) and clade 2 (Actinobacteria), both monoderm bacteria [1,16,32]. N. defluvii is a chemolithoautotrophic nitrite-oxidizing diderm (Gram-negative) bacterium [37–39] that has an active coproheme decarboxylase. It is therefore the first reported diderm representative that uses the coproporphyrin-dependent heme biosynthesis pathway. While in principal heme b was formed by NdChdC upon addition of H2O2, the enzyme was prone to heme bleaching during the reaction. This and several other questions arise from the presented data and need to be further investigated.

The ChdC from C. diphteriae proved to be the most efficient enzyme of the tested targets within this work. It converted coproheme fastest and most complete, when titrated under identical conditions to the same H2O2 excess. CdChdC belongs to Clade 2, which is the only phylogenetic clade where an arginine is found at the position of the catalytically relevant lysine in Firmicutes ChdCs (Fig. 1) [26]. The potential mechanistic influence of the exchange of the positively charged amino acid at the respective position with another one will be subject of further studies.

In summary, we present an updated phylogeny with a clear ChdC sequence motif that should define a gene as a ChdC. We were able to verify this phylogenetic prediction only for three out of four possible ChdC targets, as the protein from S. solfataricus did not show any ChdC activity at various conditions. Analysis of the heme biosynthetic pathways also suggests that S. solfataricus does not necessarily need a ChdC, as it is equipped with a complete set of genes for the alternative heme biosynthesis pathway that utilizes siroheme. Further we show for the first time experimentally that also diderm bacteria use the coproporphyrin-dependent pathway.

Supplementary Material

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2018.01.005.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the Austrian Science Fund, FWF (Doctoral Program BioToP - Molecular Technology of Proteins W1224, and stand-alone project P29099).

Abbreviations

- ABTS

2,2′-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)

- Ahb

alternative heme biosynthesis

- CdChdC

coproheme decarboxylase from Corynebacterium diphteriae

- CgdC

coproporhyrinogen decarboxylase

- CgdH

coproporphyrinogen dehydrogenase

- ChdC

coproheme decarboxylase

- Cld

chlorite dismutase

- LmChdC

coproheme decarboxylase from Listeria monocytogenes

- NdChdC

coproheme decarboxylase from Nitropsira defluvii

- NdCld

chlorite dismutase from Nitrospira defluvii

- SaChdC

coproheme decarboxylase from Staphylococcus aureus

- SsChdC

coproheme decarboxylase from Sulfolobus solfataricus

References

- [1].Dailey HA, Gerdes S, Dailey TA, Burch JS, Phillips JD. Noncanonical coproporphyrin-dependent bacterial heme biosynthesis pathway that does not use protoporphyrin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(7):2210–2215. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416285112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Dailey TA, Boynton TO, Albetel AN, Gerdes S, Johnson MK, Dailey HA. Discovery and Characterization of HemQ: an essential heme biosynthetic pathway component. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(34):25978–25986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.142604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lobo SA, Scott A, Videira MA, Winpenny D, Gardner M, Palmer MJ, Schroeder S, Lawrence AD, Parkinson T, Warren MJ, Saraiva LM. Staphylococcus aureus haem biosynthesis: characterisation of the enzymes involved in final steps of the pathway. Mol Microbiol. 2015;97(3):472–487. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Celis AI, Streit BR, Moraski GC, Kant R, Lash TD, Lukat-Rodgers GS, Rodgers KR, DuBois JL. Unusual peroxide-dependent, heme-transforming reaction catalyzed by HemQ. Biochemistry. 2015;54(26):4022–4032. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hofbauer S, Mlynek G, Milazzo L, Pühringer D, Maresch D, Schaffner I, Furtmüller PG, Smulevich G, Djinovic-Carugo K, Obinger C. Hydrogen peroxidemediated conversion of coproheme to heme b by HemQ-lessons from the first crystal structure and kinetic studies. FEBS J. 2016;283(23):4386–4401. doi: 10.1111/febs.13930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Maixner F, Wagner M, Lücker S, Pelletier E, Schmitz-Esser S, Hace K, Spieck E, Konrat R, Le Paslier D, Daims H. Environmental genomics reveals a functional chlorite dismutase in the nitrite-oxidizing bacterium 'Candidatus Nitrospira defluvii'. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10(11):3043–3056. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kostan J, Sjöblom B, Maixner F, Mlynek G, Furtmüller PG, Obinger C, Wagner M, Daims H, Djinović-Carugo K. Structural and functional characterisation of the chlorite dismutase from the nitrite-oxidizing bacterium “Candidatus Nitrospira defluvii”: identification of a catalytically important amino acid residue. J Struct Biol. 2010;172(3):331–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hofbauer S, Schaffner I, Furtmüller PG, Obinger C. Chlorite dismutases - a heme enzyme family for use in bioremediation and generation of molecular oxygen. Biotechnol J. 2014;9(4):461–473. doi: 10.1002/biot.201300210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Goblirsch B, Kurker RC, Streit BR, Wilmot CM, DuBois JL. Chlorite dismutases, DyPs, and EfeB: 3 microbial heme enzyme families comprise the CDE structural superfamily. J Mol Biol. 2011;408(3):379–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.02.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zámocký M, Hofbauer S, Schaffner I, Gasselhuber B, Nicolussi A, Soudi M, Pirker KF, Furtmüller PG, Obinger C. Independent evolution of four heme peroxidase superfamilies. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2015;574:108–119. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2014.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Blanc B, Mayfield JA, McDonald CA, Lukat-Rodgers GS, Rodgers KR, DuBois JL. Understanding how the distal environment directs reactivity in chlorite dismutase: spectroscopy and reactivity of Arg183 mutants. Biochemistry. 2012;51(9):1895–1910. doi: 10.1021/bi2017377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hofbauer S, Gysel K, Bellei M, Hagmüller A, Schaffner I, Mlynek G, Kostan J, Pirker KF, Daims H, Furtmüller PG, Battistuzzi G, et al. Manipulating conserved heme cavity residues of chlorite dismutase: effect on structure, redox chemistry, and reactivity. Biochemistry. 2014;53(1):77–89. doi: 10.1021/bi401042z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hofbauer S, Howes BD, Flego N, Pirker KF, Schaffner I, Mlynek G, Djinovic-Carugo K, Furtmüller PG, Smulevich G, Obinger C. From chlorite dismutase towards HemQ - the role of the proximal H-bonding network in heme binding. Biosci Rep. 2016;36(2):e00312. doi: 10.1042/BSR20150330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hofbauer S, Hagmüller A, Schaffner I, Mlynek G, Krutzler M, Stadlmayr G, Pirker KF, Obinger C, Daims H, Djinović-Carugo K, Furtmüller PG. Structure and heme-binding properties of HemQ (chlorite dismutase-like protein) from Listeria monocytogenes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2015;574:36–48. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Mayfield JA, Hammer ND, Kurker RC, Chen TK, Ojha S, Skaar EP, DuBois JL. The chlorite dismutase (HemQ) from Staphylococcus aureus has a redox-sensitive heme and is associated with the small colony variant phenotype. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(32):23488–23504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.442335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Dailey HA, Dailey TA, Gerdes S, Jahn D, Jahn M, O'Brian MR, Warren MJ. Prokaryotic heme biosynthesis: multiple pathways to a common essential product. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2017;81(1) doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00048-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(5):1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(10):2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14(6):1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Sato Y, Morishima K. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D353–D361. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Yang J, Yan R, Roy A, Xu D, Poisson J, Zhang Y. The I-TASSER Suite: protein structure and function prediction. Nat Methods. 2015;12(1):7–8. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Chovancova E, Pavelka A, Benes P, Strnad O, Brezovsky J, Kozlikova B, Gora A, Sustr V, Klvana M, Medek P, Biedermannova L, et al. CAVER 3.0: a tool for the analysis of transport pathways in dynamic protein structures. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8(10):e1002708. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hofbauer S, Gysel K, Mlynek G, Kostan J, Hagmüller A, Daims H, Furtmüller PG, Djinović-Carugo K, Obinger C. Impact of subunit and oligomeric structure on the thermal and conformational stability of chlorite dismutases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1824(9):1031–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang RY, Venter JC, Hutchison CA, Smith HO. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods. 2009;6(5):343–345. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Celis AI, DuBois JL. Substrate, product, and cofactor: the extraordinarily flexible relationship between the CDE superfamily and heme. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2015;574:3–17. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Celis AI, Gauss GH, Streit BR, Shisler K, Moraski GC, Rodgers KR, Lukat-Rodgers GS, Peters JW, DuBois JL. Structure-based mechanism for oxidative decarboxylation reactions mediated by amino acids and heme propionates in coproheme decarboxylase (HemQ) J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139(5):1900–1911. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b11324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kühner M, Haufschildt K, Neumann A, Storbeck S, Streif J, Layer G. The alternative route to heme in the methanogenic archaeon Methanosarcina barkeri. Archaea. 2014:327637. doi: 10.1155/2014/327637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Layer G, Moser J, Heinz DW, Jahn D, Schubert WD. Crystal structure of coproporphyrinogen III oxidase reveals cofactor geometry of Radical SAM enzymes. EMBO J. 2003;22(23):6214–6224. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hofbauer S, Dalla Sega M, Scheiblbrandner S, Jandova Z, Schaffner I, Mlynek G, Djinovic-Carugo K, Battistuzzi G, Furtmüller PG, Oostenbrink C, Obinger C. Chemistry and molecular dynamics simulations of heme b-HemQ and coproheme-HemQ. Biochemistry. 2016;55(38):5398–5412. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Füreder S. Functional Analyses of Chlorite-dismutase like Proteins from Listeria Monocytogenes and Nitrobacter Winogradskyi. University of Vienna; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Streit BR, Celis AI, Shisler K, Rodgers KR, Lukat-Rodgers GS, DuBois JL. Reactions of ferrous coproheme decarboxylase (HemQ) with O2 and H2O2 yield ferric heme b. Biochemistry. 2017;56(1):189–201. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Dailey HA, Gerdes S. HemQ: an iron-coproporphyrin oxidative decarboxylase for protoheme synthesis in Firmicutes and Actinobacteria. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2015;574:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].She Q, Singh RK, Confalonieri F, Zivanovic Y, Allard G, Awayez MJ, Chan-Weiher CC, Clausen IG, Curtis BA, De Moors A, Erauso G, et al. The complete genome of the crenarchaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus P2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(14):7835–7840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141222098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Brock TD, Brock KM, Belly RT, Weiss RL. Sulfolobus: a new genus of sulfuroxidizing bacteria living at low pH and high temperature. Arch Mikrobiol. 1972;84(1):54–68. doi: 10.1007/BF00408082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Fawal N, Li Q, Savelli B, Brette M, Passaia G, Fabre M, Mathé C, Dunand C. PeroxiBase: a database for large-scale evolutionary analysis of peroxidases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue):D441–D444. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Maaty WS, Wiedenheft B, Tarlykov P, Schaff N, Heinemann J, Robison-Cox J, Valenzuela J, Dougherty A, Blum P, Lawrence CM, Douglas T, et al. Something old, something new, something borrowed; how the thermoacidophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus responds to oxidative stress. PLoS One. 2009;4(9):e6964. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ehrich S, Behrens D, Lebedeva E, Ludwig W, Bock E. A new obligately chemolithoautotrophic, nitrite-oxidizing bacterium, Nitrospira moscoviensis sp. nov. and its phylogenetic relationship. Arch Microbiol. 1995;164(1):16–23. doi: 10.1007/BF02568729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Spieck E, Hartwig C, McCormack I, Maixner F, Wagner M, Lipski A, Daims H. Selective enrichment and molecular characterization of a previously uncultured Nitrospira-like bacterium from activated sludge. Environ Microbiol. 2006;8(3):405–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Lücker S, Wagner M, Maixner F, Pelletier E, Koch H, Vacherie B, Rattei T, Damsté JS, Spieck E, Le Paslier D, Daims H. A Nitrospira metagenome illuminates the physiology and evolution of globally important nitrite-oxidizing bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(30):13479–13484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003860107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.