In this issue of AJPH, Yakubovich et al. (p. 957;e1) present a systematic review of predictors of women’s intimate partner violence (IPV) experiences. IPV is a global public health concern and includes experiences of physical and sexual violence, stalking, and psychological aggression at the hands of a current or ex-partner. The World Health Organization estimates that 35% of women across the globe have experienced IPV.1 IPV has profound effects on the physical, mental, and emotional health of those affected and profound social and economic consequences.

Yakubovich et al. conducted a rigorous systematic review, ascertained from longitudinal cohort studies, of risk and protective factors associated with women’s self-reported experiences of IPV. The authors examined 30 years’ worth (1986–2016) of published and unpublished English-language cohort studies, which they identified through a search of 16 online databases. They reviewed the titles or abstracts of more than 18 600 publications for inclusion. In this initial screening, the authors eliminated ineligible studies and selected 309 publications for full-text review. Of these, 60 met study inclusion criteria: quantitative analysis of at least one risk factor for IPV; women’s self-report of physical, sexual, or psychological IPV; women being at least 19 years old; and measurement of the study risk factors before the assessment of IPV. Although the overwhelming majority (80%) of studies reviewed originated in the United States, studies from all countries and regions were eligible.

Yakubovich et al. evaluated risk and protective factors associated with IPV. They found the strongest evidence that unplanned pregnancy and having parents with less than high school education were associated with higher likelihood of IPV, whereas being older and married were protective. This systematic review and meta-analysis provides valuable insights into the breadth and quality of risk factor research and highlights important directions for future research.

QUALITY OF INTIMATE PARTNER VIOLENCE RESEARCH

Yakubovich et al. evaluated study quality using the Cambridge Quality Checklists, which weighed the impact of sampling, participation rates, sample size, measure of risk or protective factor, validation of outcome measures, and adjustment of confounding.2 The criteria of prospective assessment of outcome and longitudinal follow-up were restricted at the level of study inclusion criteria. The authors combined risk factors that were present in multiple independent studies using similar methodology (i.e., similar variable definitions) in a random-effects meta-analysis.

The review of Yakubovich et al. highlights a number of important features of the epidemiologic research on women’s IPV experiences. First, and most heartening, the overall assessment of quality of studies was high (62%–92%). The most common limitations were poor participation rates and the absence of random sampling. However, one third of the studies reported the use of IPV measures with either poor or inadequately reported validity or reliability. Further, no studies included all four of the main classifications of IPV: physical violence, sexual violence, stalking, and psychological aggression3; only seven (12%) studies measured psychological, physical, and sexual IPV. Among the remaining studies, most assessed physical IPV (98%), and 40% and 32% assessed sexual and psychological IPV, respectively. The implementation of consistent and comprehensive definitions of IPV is essential for actionable target selection for intervention and trend monitoring.

RESEARCH FOCUS

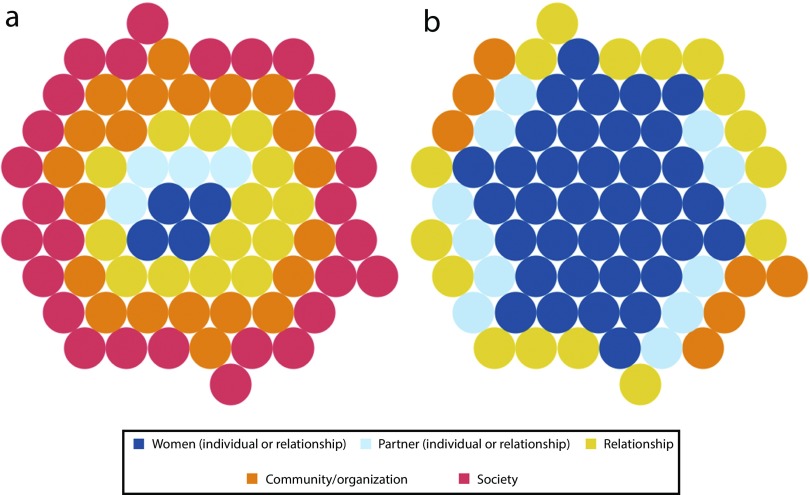

The systematic review, which classified risk and protective factors, was informed by the ecosocial framework.4 This model for IPV prevention is multilevel and intersectional—reflecting the interaction between individuals and the environment. Yakubovich et al. identified 71 risk and protective factors and classified them into four levels: individual, relationship, community, and societal. Relationship characteristics (n = 35) were the most numerous factors identified and included partner characteristics (n = 19; e.g., age, socioeconomic characteristics, alcohol use, sexual risk), individual characteristics of the women relevant to relationships (n = 9; e.g., life stress, relationship satisfaction, self-reported autonomy), and characteristics of the relationship (n = 7; e.g., marital status, relationship duration, parenting status, financial stress). Examining studies classified by unit of analysis—woman, partner, couple, community, or society (Figure 1)—shows that the published research has disproportionately focused on women’s characteristics over other units of analysis.

FIGURE 1—

Levels of Prevention of Intimate Partner Violence Comparing (a) Conceptual Ecosocial Framework With (b) Results From a Systematic Review of Cohort Studies

Considerable research effort has been expended to examine the role of women in their experiences of IPV. Supplemental Tables 8 through 34 in Appendix B of Yakubovich et al. carefully document the attention paid to women’s individual-level characteristics that predispose them to or protect them from IPV: their use of alcohol, marijuana, and other substances; their experiences with depression, posttraumatic stress, and suicide; their experiences of previous violence, forced sexual intercourse, child abuse, and interparental IPV; their physical health, limitations, and HIV status; their sexual histories; their personalities; and their aggressive tendencies and hostility.

The second level of the ecosocial model—relationship—also included a significant focus on the experiences and history of the individual woman. For example, whether the woman was from a single mother family, whether she was satisfied in the relationship, and whether she had a positive relationship with her parents.

These lists are both staggering in their specificity and heartbreaking when considered within the context of structural gender-based inequities. Research has disproportionately focused on the level and unit with the least agency or ability to make choices and transform choices into desirable outcomes. Exacerbating characteristics, including ethnicity, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic position, may attenuate or exacerbate an individual’s woman’s risk, but it is essential to consider gender inequity as a fundamental cause of IPV.5 Women’s social positioning may result in an underlying vulnerability to IPV. As a research community, we must push to measure the multilevel and contextual predictors of IPV.

This review also highlights the dearth of data on partner characteristics, and community- and societal-level risk and protective factors limited inferences related to these critical constructs. The strongest evidence was limited to factors that were individual characteristics of women who report IPV. Of the 19 variables reflecting partner characteristics, only two (alcohol use and parental monitoring) had enough studies for inclusion in meta-analyses. This lack of evidence, combined with inconsistency in measuring partner characteristics, attitudes, and behaviors, is an important gap in the field.

The most disheartening finding of this systematic review is that few studies examined community- and societal-level risk factors. Although Yakubovich et al. implemented a rigorous search, they were not able to identify a single cohort study that examined societal contexts in which IPV exists and persists. Although the focus on longitudinal studies may have increased the emphasis on traditional, established measures of individual and relationship characteristics over measures of context and interplay among levels, clearly more research should pay attention to community- and societal-level predictors of IPV. Major IPV prevention initiatives, including those spearheaded by the United Nations and World Health Organization, emphasize the importance of comprehensive, multilevel interventions for the reduction of IPV.

SUMMARY

The systematic review by Yakubovich et al. provides essential insights into the state of IPV research from prospective cohort studies. Future research and funding should be directed to analyses of IPV predictors that focus on both the multiple levels of causation of IPV and the interactions among levels. Moreover, our understanding of individuals and relationships is limited when studying them ex vivo, or removed from their environments. Finally, researchers should remain mindful of the unintended consequence of “blaming the victim,” that is, focusing research and interventions at the level of the woman experiencing IPV—to the exclusion of other causes—without a concrete analysis of the role of structural gender inequities and women’s agency.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author would like to thank Mary M. Gerkovich, PhD, for her comments on a draft of this editorial.

Footnotes

See also Yakubovich et al., p. 957;e1.

REFERENCES

- 1.United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. The World’s Women 2015: Trends and Statistics. New York, NY: United Nations Publications; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray J, Farrington DP, Eisner MP. Drawing conclusions about causes from systematic reviews of risk factors: the Cambridge Quality Checklists. J Exp Criminol. 2009;5(1):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breiding MJ, Basile KC, Smith SG, Black MC, Mahendra R. Intimate Partner Violence Surveillance: Uniform Definitions and Recommended Data Elements, Version 2.0. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dahlberg LL, Krug EG. Violence—a global public health problem. In: Krug E, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R, editors. World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002. pp. 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;35(spec no):80–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]