Abstract

Proponents of survey evaluation have long advocated the integration of qualitative and quantitative methodologies, but this recommendation has rarely been practiced. We used both methods to evaluate the “Everyday Discrimination” scale (EDS), which measures frequency of various types of discrimination, in a multi-ethnic population. Cognitive testing included 30 participants of various race/ethnic backgrounds and identified items which were redundant, unclear, or inconsistent (e.g., cognitive challenges in quantifying acts of discrimination). Psychometric analysis included secondary data from two national studies, including 570 Asian Americans, 366 Latinos, and 2,884 African Americans, and identified redundant items, as well as those exhibiting differential item functioning (DIF) by race/ethnicity. Overall, qualitative and quantitative techniques complemented one another, as cognitive interviewing findings provided context and explanation for quantitative results. Researchers should consider further how to integrate these methods into instrument pretesting as a way to minimize response bias for ethnic and racial respondents in population-based surveys.

Introduction

It is now generally recognized that new instruments require some form of pretesting or evaluation before they are administered in the field (Presser et al. 2004). As such, qualitative and quantitative methods for analyzing questionnaires have proliferated widely over the last twenty years. However, these developments tend to occur in disparate fields in an uncoordinated manner where varied disciplines fail to collaborate or to align procedures. Quantitative methods normally derive from a psychometric orientation, and are closely associated with academic fields such as psychology and education (Nunnally and Bernstein 1994). Qualitative methods for the evaluation of survey items largely developed within the field of sociology and more recently, through the interdisciplinary science known as Cognitive Aspects of Survey Methodology (CASM), which emphasizes the intersection of applied cognitive psychology and survey methods (Jabine et al. 1984). CASM has been largely responsible for spawning cognitive interviewing (as described in other papers in this issue).

Whereas psychometrics traditionally focuses on the assessment of reliability and validity of scales from collected data of relatively large sample sizes, cognitive interviewing examines item performance with small samples but provides a flexible and in-depth approach to examine cognitive issues and alternative item wordings when problems arise during interviews. Given that quantitative-psychometric and qualitative-cognitive approaches overlap, and mixed-methods research is viewed as a valuable endeavor (Johnson and Onwuegbuzie 2004; Tashakkori and Teddlie 1998), it seems appropriate that researchers would combine these techniques when testing questionnaires for population-based surveys. However, such collaborations are rare, perhaps due to the disciplinary barriers and differences in procedural requirements. The goal of the current project is to bridge this gap, by applying both psychometric and cognitive methods to evaluate the Everyday Discrimination Scale (EDS; Williams et al. 1997), and to determine the degree to which these approaches conflict, support one another, or address different aspects of potential survey error. This study does not substitute for a full psychometric evaluation of the EDS, or a full description of proper use of each of the methods. No previous expectations were made with regard to the level or type of correspondence between the qualitative and quantitative methods. Instead, the study seeks to identify the key ways in which qualitative and quantitative testing enable questionnaire evaluation and identification of problems that may lead to response bias. Based on a consideration of the general nature of each method, we expected that cognitive interviewing would identify problems related to question interpretation and comprehension; whereas psychometric methods would identify items that did not fit well with others as a measure of the singular construct of racial-ethnic discrimination.

Methods

The EDS questionnaire measures perceived discrimination (Williams et al. 1999; Kessler et al. 1999; De Vogli et al. 2007). This scale has been used in a variety of populations in the U.S., including African Americans, Asian Americans, and Latinos, and increasingly, has been applied worldwide, including studies in Japan (Asakura et al. 2008) and South Africa (Williams et al., 2008). However, despite wide usage of this scale, relatively little empirical work has been done to examine its cross-cultural validity. Further, since its development one decade ago, little research has been conducted to revise the scale (Hunte and Williams in press).

The present study demonstrates a two-part mixed-methods approach to evaluate (and eventually to refine) the EDS1. The first part involved a qualitative analysis of the instrument with a sample of 30 participants, through cognitive interviews of individuals from multiple racial/ethnic groups. The goals were to provide guidance on modifying item structure, word phrasing, and response categories. The second part of the study analyzed secondary data from two complementary datasets, the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS) and the National Survey of American Life (NSAL). This part of the study used psychometric methods to examine the performance of EDS items, including testing for differential item functioning (DIF) across race/ethnicity.

Questionnaire

The EDS is a nine-item self-reported instrument designed to elicit perceptions of unfair treatment through items such as “you are treated with less respect than other people” and “you are called names or insulted” (Williams et al. 1999). The variant of the EDS selected (from Williams et al., 1997) uses a 6-point scale with response options “Never”, “Less than once a year”, “A few times a year”, “A few times a month”, “At least once a week”, and “Almost everyday.” Higher scores on the EDS indicate higher levels of discrimination.

Items within the NLAAS study were worded identically to the NSAL, except that the NLAAS revised item #7 from “People act as if they're better than you are” to “People act as if you are not as good as they are.” After responding to these nine items, participants are asked to identify the main attribute for the discriminatory acts, such as discrimination due to race, age, or gender. A respondent replying “never” to all 9 items would skip the following attribution question.

Cognitive Testing Sample and Procedure

Thirty participants were recruited for in-person cognitive interviews (see Table 1). Participants were 18 years or older, living in the Washington DC metropolitan area, and self-identified during recruitment as Asian American, Hispanic or Latino, Black or African American, American Indian/Alaska Native, or Non-Hispanic White. Participants were recruited via bulletin boards, listservs, community contacts, ad postings, and through ‘snowball’ sampling in which participants identified other eligible individuals. All participants agreed that they were comfortable conducting the face-to-face interview session entirely in English. Cognitive interviews focused on item clarity, redundancy, and appropriateness (in terms of whether items captured the relevant discrimination-related experiences of the tested individual). Concurrent probes consisted of pre-scripted and unscripted queries (Willis, 2005). An example of a pre-scripted query comes from the EDS item on courtesy and respect. The interviewers asked each participant: “I asked about ‘courtesy’ and ‘respect’: To you, are these the same or different?” Interviewers were also encouraged to rely on spontaneous or emergent probes (Willis 2005) to follow-up unanticipated problems (a copy of the cognitive protocol is available from the lead author, upon request). In particular, interviewers probed the adequacy of the time frame, because some questions include a past 12-month time frame, whereas other questions asked about “ever.” Interviewers also investigated participants’ ability to understand key terms used in questions, in part through the use of the generic probe, “Tell me more about that.”

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Cognitive Interview Participants

| Group | Gender | Birthplace | Age at Entry to US |

Current Age |

Language | Education |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Asian | 4 men | Taiwan (2) | 3, 9, 18, 23, 26, 51 | 18–29 (2) | Chinese | GED or high school (2) |

| 2 women | Korea | 30–49 (3) | Korean | Some college (1) | ||

| Philippines | 50+ (1) | Tagalog | College graduate (1) | |||

| Vietnam | Japanese | Post graduate (2) | ||||

| Japan | Mandarin | |||||

| Vietnamese | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 3 men | Colombia | 3, 9, 12, 20, 28 | 18–29 (3) | Spanish | GED or high school (1) |

| 3 women | Peru | 30–49 (1) | Some college (3) | |||

| Mexico (2) | 50+ (2) | College graduate (1) | ||||

| Chile | Post graduate (1) | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Black or African-American | 3 men | NA | NA | 18–29 (3) | NA | GED or high school (2) |

| 3 women | 30–49 (2) | Some college (2) | ||||

| 50+ (1) | College graduate (1) | |||||

| Post graduate (1) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Native American | 2 men | NA | NA | 18–29 (1) | NA | Some college (3) |

| 4 women | 30–49 (4) | College graduate (1) | ||||

| 50+ (1) | Post graduate (2) | |||||

|

| ||||||

| White | 3 men | NA | NA | 18–29 (3) | NA | 11th grade or less (1) |

| 3 women | 30–49 (2) | GED or high school (1) | ||||

| 50+ (1) | Technical school (1) | |||||

| College graduate (2) | ||||||

| Post graduate (1) | ||||||

For each item, cognitive interviews attempted to ascertain whether it was more effective (1) to first ask about unfair treatment generally, and to then follow with a question asking about attribution of the unfair treatment (referred to as “two-stage” attribution of discrimination); or (2) to refer to the person’s race/ethnicity directly within each question (referred to as “one-stage” attribution). An example of two-stage attribution would be to follow the 9 EDS items with “what is the main reason for these experiences of unfair treatment – is it due to race, ethnicity, gender, age, etc.?” An example of one-stage attribution version would be, “How often have you been treated with less respect than other people because you are [Latino]2?”

All interviews were conducted by seven senior survey methodologists at Westat (a contract research organization in Rockville, Maryland) and lasted about an hour (interviews were evenly divided across interviewers such that each one conducted between 2 and 7 interviews). Interviews were audio-recorded, and interviewers took written notes during the course of the interview, and made additional notes as they reviewed the recordings.

Data for Psychometric Testing

Secondary data were from NLAAS and NSAL, which are part of the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiological Studies designed to provide national estimates of mental health and other health data for different populations (Pennell et al. 2004; Alegria et al. 2004). The NLAAS was a population-based survey of persons of Asian (n=2095) and Latino (n=2554) background conducted from 2002 to 2003. The NLAAS survey involved a stratified area probability sampling method, the details of which are reported elsewhere (Alegria et al. 2004; Heerenga et al. 2004). Respondents were adults, ages 18 and over, residing in the United States. Interviews were conducted face-to-face or in rare cases, via telephone. The overall response rate was 67.6% and 75.5% for Asian Americans and Latinos, respectively.

The NSAL was a national household probability sample of 3570 African Americans, 1621 blacks of Caribbean descent and 891 non-Hispanic whites, aged 18 and over. Interviews were conducted face-to-face, in English, using a computer-assisted personal interview. Data were collected between 2001 and 2003. The overall response rate was 72.3% for whites; 70.7% for African Americans, and 77.7% for Caribbean blacks.

Results

Cognitive Testing Results

We analyzed the narrative statements after conducting all 30 interviews. A key issue in cognitive interviewing is how best to analyze these narrative statements to draw appropriate conclusions concerning question performance (Miller, Mont, Maitland, Altman, and Madans, in press). For the current study, cognitive interviewing results were analyzed according to the common approach involving a ‘qualitative reduction’ scheme, based on Willis (2005), consisting of:

Interview-level review: The results for each participant were first reviewed by that interviewer. This procedure maintained a ‘case history’ for each interview, in order to facilitate detection of dependencies or interactions across items, where the cognitive processing of one item may affect that of another.

Item-level review/aggregation: Each of the seven interviewers then aggregated the written results across all of their own interviews, for each of the nine EDS items, searching for consistent themes across these interviews.

Interviewer aggregation: Interviewers met as a group to discuss, both overall and on an item-by-item basis, common trends, or discrepancies in observations between interviewers.

Final compilation: The lead researcher used results from (b) and notes taken during (c) to produce a qualitative summary for each item, representing findings across both interviews and interviewers. These final summaries collated information about the frequencies of problems in a general manner, without precisely enumerating problem frequency. For example, the final compilation indicated whether each identified problem occurred for No, A few, Some, Most, or All participants.

Cognitive testing uncovered several results that suggest the need for refinement of the EDS related to item redundancy, clarity, and adequacy of questions. However, differences by race/ethnicity were not as pronounced. Following are some of the key findings related to each criterion.

Redundant items. Some respondents indicated that the EDS item on “courtesy” (Item #1) was redundant with the item on “respect” (Item #2). All subjects were directed to explicitly compare the two items (i.e., cognitive probe) and tended to report that “respect” was a more encompassing term. Accordingly, the investigators suggested that item #1 be removed from the instrument.

Item vagueness. The item “You receive poorer service than other people at restaurants and stores” was found to be vague, as some respondents believed that everyone has received poor service, so that the item did not necessarily capture discriminatory acts. Therefore, it seemed appropriate to reword the item to instead ask: “…how often have you been treated unfairly at restaurants or stores?” In addition, respondents suggested that the item related to being “called names or insulted” (Item #8) was unclear, especially to members of groups who reported few instances of discrimination. Accordingly, we recommended removal of this item.

Response category problems. In each cognitive interview, we investigated the use of frequency categories (e.g. “less than once a year; “almost every day”) compared to more subjective quantifiers (e.g. “Never”; “often”). This was evaluated initially by observing or asking how difficult it was for subjects to select a frequency response category, and then asking them if it would be easier or more difficult to rely on the subjective categories. In the analysis phase, interviewers agreed that subjects found it very difficult to recall and enumerate precisely defined events, but were able to provide the more general assessment measured by the subjective measures.

Reference period problems. The longer the reference period, the more difficulty respondents reported having when attempting to recall particular experiences of unfair treatment. An “ever” period was found to be especially challenging when respondents were asked to quantify their experiences. The cognitive interview summary suggested incorporating a 12-month period directly into each question in order to ease the reporting burden.

Problems in assigning attribution. Members of all groups, and white respondents in particular, found the intent of several EDS items to be unclear. For example, one participant commented, “I got called names in school – Does that count?” In general, we found that adding the phrase “…because you are [SELF-REPORTED RACE/ETHNICITY]” (e.g., “because you are black”) into each question facilitated interpretation for respondents. On the other hand, we found that respondents were not always able to ascribe discriminatory or unfair events to race/ethnicity. Making no initial reference to race or ethnicity (two-stage attribution) elicited a broader set of personal and demographic factors that could underpin discriminatory and unfair acts such as: age, gender, sexual orientation, religion, weight, income, education, and accent (given that the scales incorporated the two-stage approach to measuring discrimination). We concluded that the selected approach should depend mainly on the investigator’s research objectives. Williams and Muhammed (2009) provide a discussion about the theoretical rationale that underlies the one-stage versus two-stage attribution approaches.

Quantitative-Psychometric Testing Results

The combined NLAAS and NSAL datasets resulted in the identification of 2,095 Asian Americans, 2,554 Latinos, 5,191 African Americans, and 591 Non-Hispanic Caucasians. Of the 10,431 respondents in the study, 31% of Asian Americans, 36% of Latinos, 29% of African Americans, and 45% of Non-Hispanic Caucasians reported “never” to all nine items of the EDS and were excluded from the psychometric analyses. Further, among those who did report any unfair treatment, 32% Asian Americans, 30% Latinos, 16% African Americans, and 49% Non-Hispanic Caucasians attributed their any unfair treatments to traits such as height, weight, gender, or sexual orientation. These respondents were also removed from further analyses because the research team was focused on racial/ethnic discrimination. To avoid potential confounding due to translation, our analyses only examined respondents who took the English-version of the EDS (approximately 72% of Asian Americans, 42% of Hispanics, and all the African Americans and Non-Hispanic whites). The non-Hispanic white sample reporting unfair treatment due to race included only 51 respondents, which was too small for meaningful psychometric evaluation, so they were also excluded from our study sample.

After the exclusions, our analytic dataset consisted of 570 Asian Americans (46% women), 366 Latinos (48% women), and 2,884 African Americans (60% women). These respondents reported one or more acts of unfair treatment and attributed the unfair treatment due to their ancestry, national origin, ethnicity, race, or skin color. Percentage of respondents with less than a high school education included 21% African Americana, 20% Latinos, and 5% Asian Americans. Ages ranged from 18 to 91 years with means of 41 years for African Americans, 38 years for Asian Americans, and 35 years for Latinos.

The EDS was examined using a series of psychometric methods, in turn, with the goal of examining the functioning of each individual item alone (e.g., participants use of response options) and how the items correlate and form an overall unidimensional measure of discrimination (e.g., using factor analysis and item response theory methodology). Item and scale evaluation was performed both within and across the three race/ethnicity groups. These set of approaches are consistent and appropriate for the psychometric evaluation of a multi-item questionnaire (Reeve et al. 2007).

Descriptive statistics

Initially, item descriptive statistics included measures of central tendency (mean), spread (standard deviation), and response category frequencies. In examining the distribution of response frequencies by race/ethnicity for each item across the 6-point Likert type scale, we found that very few people endorsed “almost every day” for all nine items, and few reported “at least once a week” for eight items. An independent study examining discrimination in incoming students at US law schools also found the highest response options were rarely endorsed (Panter et al. 2008).

Differences in reported experiences of unfair treatment by race/ethnicity are presented in Table 2, which provides means and standard deviations for each group on an item-by-item basis. For all items except item 9 (“You were threatened or harassed), African Americans reported greater frequency of unfair treatment on average than did Asian Americans (p <= .01). African Americans reported more than Latinos for items #4, #6, and #7. Averaging across all 9 items and placing scores on a 0 to 100 metric, African Americans had significantly higher mean scores (31.0) than either Latinos (26.8) or Asian Americans (23.3).

Table 2.

Comparisons among Asian-Americans, Latinos, and African-Americans of Reports of Unfair Treatment.

| Asian Am (n = 570) Mean* (SD) |

Latinos (n = 366) Mean* (SD) |

African Am (n = 2884) Mean* (SD) |

Contrasts*** Identifying significant differences (α <= .01) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | You are treated with less courtesy than other people. | 1.66 (0.96) | 1.82 (1.25) | 1.91 (1.23) | Asian Am & African Am. |

| 2 | You are treated with less respect than other people. | 1.46 (0.91) | 1.63 (1.24) | 1.77 (1.20) | Asian Am. & African Am. |

| 3 | You receive poorer service than other people at restaurants or stores. | 1.46 (0.90) | 1.55 (1.15) | 1.63 (1.15) | Asian Am. & African Am. |

| 4 | People act as if they think you are not smart. | 1.33 (0.92) | 1.73 (1.43) | 1.96 (1.42) | Asian Am. & African Am. Asian Am. & Latinos Latinos & African Am. |

| 5 | People act as if they are afraid of you. | 0.96 (0.96) | 1.21 (1.32) | 1.36 (1.42) | Asian Am. & African Am. Asian Am. & Latinos |

| 6 | People act as if they think you are dishonest. | 0.81 (0.85) | 1.04 (1.15) | 1.28 (1.34) | Asian Am. & African Am. Asian Am. & Latinos Latinos & African Am. |

| 7 | People act as if they’re better than you are.** | 1.32 (0.99) | 1.63 (1.31) | 2.38 (1.51) | Asian Am. & African Am. Asian Am. & Latinos Latinos & African Am. |

| 8 | You are called names or insulted. | 0.85 (0.89) | 0.93 (1.18) | 0.98 (1.22) | Asian Am. & African Am. |

| 9 | You are threatened or harassed. | 0.58 (0.67) | 0.58 (0.86) | 0.67 (0.92) |

Note:

Individual scores ranged from 0 (“never”) to 5 (“almost every day”).

Question 7 is worded as “People act as if you are not as good as they are” for Asian Americans and Latinos.

Contrasts were performed post hoc after significant results from analysis of variance tests.

Correlational and factor structure

Next, to determine the extent to which the EDS items appeared to measure the same construct, we reviewed the inter-item correlations. Similar patterns were observed in the correlation matrices across the three racial/ethnic groups. Most of the items are moderately correlated (between .30 and .50) with the other items in the scale. Consistent with findings from cognitive interviews, the first two items, “you are treated with less courtesy than other people” and “you are treated with less respect than other people,” were highly correlated (.69 to .72). The last two items, “you are called names or insulted” and “you are threatened or harassed,” also show a moderately strong positive relationship (.54 to .68). These high correlations raise concerns that the courtesy/respect items in particular are redundant with each other. Redundant items may increase the precision of the scale but do little to increase our understanding of what accounts for the variation in item responses. Further, redundant item pairs found to be locally dependent may affect subsequent IRT analyses which assume all items are locally independent after removing the shared variance due to the primary factor being measured. Item correlations with the total EDS score (i.e., summing the items together) were moderate to high (.46 to .67) suggesting the items tap into a common measure of unfair treatment. Scale internal consistency reliability was high (ranged from .84 to .88 across the groups) and sufficient for using the EDS for group level comparisons (Nunnally & Bernstein. 1994).

We followed the assessment of the inter-item correlations with a test to confirm the factor structure of the EDS as a single factor model in each of the race/ethnic groups. Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were used to examine the dimensionality of the EDS, as the original formulation of the EDS instrument presumed a unidimensional construct (Williams et al. 1997) and the single factor structure was confirmed in a follow-up study (Kessler et al. 1999) and measured as a single construct in another multi-race/ethnic study (Gee, et al., 2007). Factor analyses were carried out using MPLUS (version 4.21) software (Muthen & Muthen, Los Angeles, CA).

For the African American sample, a CFA did not show a good fit for the 9-item unidimensional model (CFI = .75, TLI = .85, SRMR = .10). To find out reasons for misfit to a single factor model, we looked at residual correlations which some the extent of excess correlations among items after extracting the covariance due to the first factor. Both the first pair of items (#1, #2) and the last (#8, #9) showed relatively large residual correlations (r = .15 and .23, respectively). A follow-up exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed which makes no assumptions on the number of factors in the data. The EFA identified two factors with the first factor showing high loadings on item #1(“you are treated with less courtesy than other people”) and item #2 (“you are treated with less respect than other people”). The remaining 7 items formed the second factor. There was a moderately strong correlation (.60) between the two factors.

These results led us to drop item #1,the “courtesy” item, from further psychometric analyses because of concerns about local dependence. The last two items were retained, but were monitored for their affect on parameter estimates in the item response theory models. The one-factor solution for the resulting reduced 8-item EDS scale had high factor loadings in the African American sample, ranging from .61 to .74. The lowest factor loading was associated with item #3, “you receive poorer service than other people at restaurants or stores.” This finding was consistent with cognitive interview results, which also highlighted problems of item clarity. The highest factor loading was associated with, “people act as if they think you are dishonest.”

The same issues identified for African Americans, including redundancy issues related to “courtesy” and “respect,” were seen for Asian Americans and Latinos. Findings of a single factor solution for the 8-item scale (removing the “courtesy” item), the magnitude of item factor loadings, and other results in the Asian Americans and Latinos were consistent to those for African Americans.

Item Response Theory analysis

Following confirmation of a single factor measure of discrimination, item response theory (IRT) was used to examine the measurement properties of each item. IRT refers to a family of models that describe, in probabilistic terms, the relationship between a person’s response to a survey question and his or her standing (level) on the latent construct that the scale measures. The latent concept we hypothesized is level of unfair treatment (i.e., discrimination). For every item in the EDS, a set of properties (item parameters) were estimated. The item slope (or discrimination3 parameter) describes how well the item performed in terms of the strength of the relationship between the item and the overall scale. The item difficulty or threshold parameter(s) identified the location along the construct’s latent continuum where the item best discriminates among individuals. Samejima’s (1969) Graded Response IRT Model was fit to the response data because the response categories consist of more than two options (Thissen et al., 2001). We used IRT model information curves to examine how well both the items and scales performed overall for measuring different levels of the latent construct. All IRT analyses were conducted using MULTILOG (version 7.03) software (Scientific Software International, Lincolnwood, IL).

IRT methods were used to examine the measurement properties of EDS items #2–9 in the full sample that included all racial/ethnic groups. The IRT model assigned a single set of IRT parameters for each item for all groups, but allowed the mean and variance to vary for each race/ethnic group.

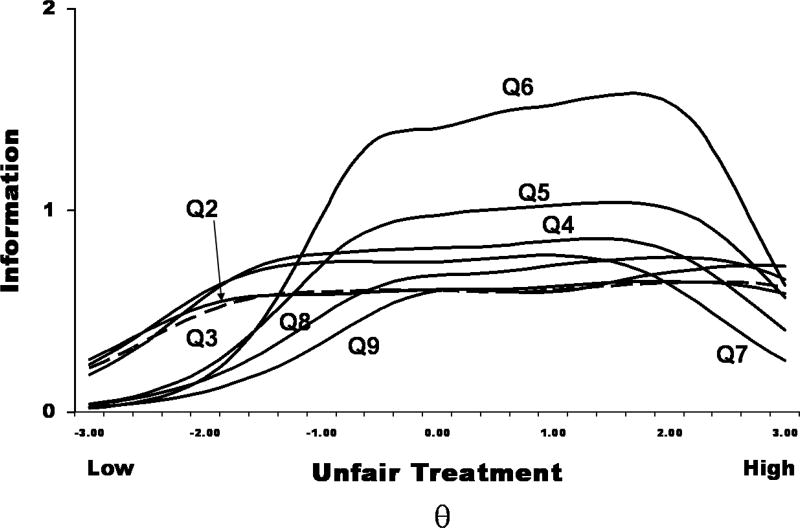

Figure 1 presents the IRT information curves for each item labeled Q2 (EDS Question 2) to Q9 (EDS Question 9). An information curve indicates the range over the measured construct (unfair treatment) for which an item provides information for estimating a person’s level of reported experiences of unfair treatment. The x-axis is a standardized scale measure of level of unfair treatment. Since the response options are capturing frequency, “level” refers to how often an unfair act was experienced by the respondent. However, “level” can also be interpreted as the severity of the unfair act as severe acts such as “threatened or harassed” are less likely to occur, and less severe acts such as “treated with less respect” are more likely to occur. Respondents who reported low levels of unfair treatment are located on the left side of the continuum and those reporting high levels of unfair treatment are located on the right. The y-axis captures information magnitude, or degree of precision for measuring persons at different levels of the underlying latent construct, with higher information denoting more precision. Question 6, “people act as if they think you are dishonest,” and question 5, “people act as if they are afraid of you,” (and which therefore ascribe negative characteristics directly to the respondent) provide the greatest amount of information for measuring people who experienced moderate to high levels of unfair treatment. Items #2, #3, #4, and #7 appear to better differentiate among people who reported low levels of unfair treatment than people who experience high levels of unfair treatment. Items #8 and #9 (which involve being actively attacked) were associated with relatively lower amount of information, but appear to capture higher levels of unfair treatment. Similar to the factor analysis and cognitive interviewing findings, item #3 (“poorer service,” dashed curve) performed relatively poorly.

Figure 1.

EDS Item Response Theory Item Information Curves

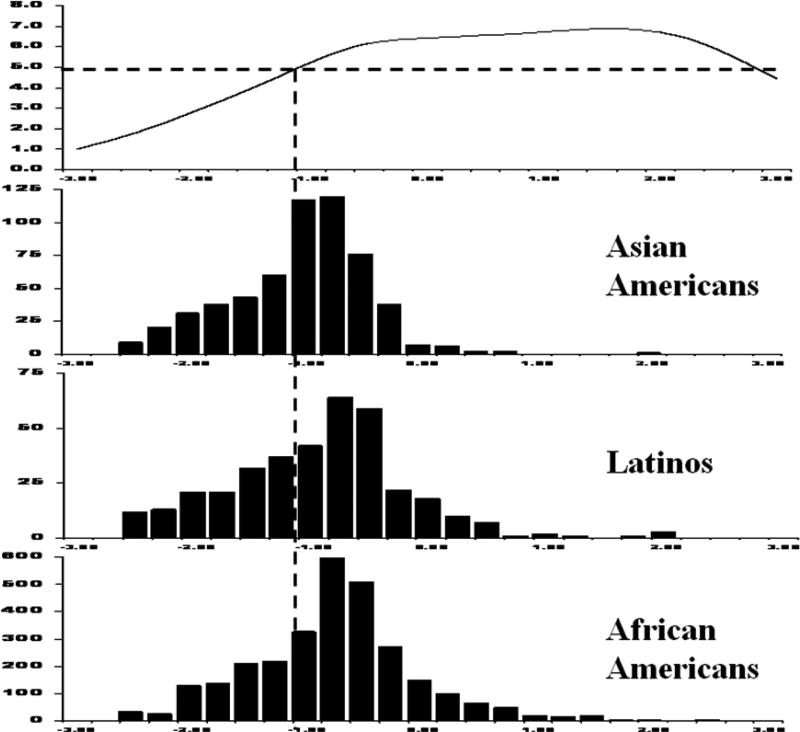

The EDS information function (top diagram in Figure 2) shows how well the reduced 8-item scale as a whole performs for measuring different levels of unfair treatment. The dashed horizontal line indicates the threshold for a scale to have an approximate reliability of .80, which is adequate for group level measurement (Nunnally and Bernstein, 1994). The EDS information curve indicates that the scale adequately measures people who experienced moderate to high levels of unfair treatment (from −1.0 to +3.0 standardized units below and above the group mean of 0). The three histograms on the bottom of Figure 2 present the IRT score distribution for each race/ethnic group along the trait continuum. The 8-item scale is reliable for the majority whose scores are to the right of the vertical dashed line, and is less precise for a substantial proportion of individuals in each group who report low levels of discrimination (to the left of the line).

Figure 2.

8-Item EDS Information Function and IRT Score Distributions by Racial/Ethnic Groups

Differential Item Functioning testing

Finally, due to the multi-racial focus of the investigation, we tested for differential item functioning (DIF). These tests were performed to identify instances in which race/ethnic groups responded differently to an item, after controlling for differences on the measured construct. Scales containing DIF items may have reduced validity for between-group comparisons, because their scores may be indicative of a variety of attributes other than those the scale is intended to measure. DIF tests were performed among the racial/ethnic groups using the IRT-based likelihood-ratio (IRT-LR) method (Thissen et al. 1993) using the IRTLRDIF (version 2.0b) software program (Thissen, Chapel Hill, NC).

Item #7 (“People act as if they’re better than you”) exhibited substantial DIF between African-Americans and Asian Americans (χ2(5) = 278.2), and between African Americans and Latinos (χ2(5) = 85.6). Given that this item was worded differently for the African Americans in the NSAL than for the Asian Americans and Latinos in the NLAAS, DIF is likely due to instrumentation differences rather than differences based on racial/ethnic group representation. This finding suggests that the DIF method is sensitive to wording differences on the same question administered to different groups, and in one sense serves as a type of ‘calibration check’ on our techniques (i.e., the effects of a wording change between groups is successfully identified in the DIF results).

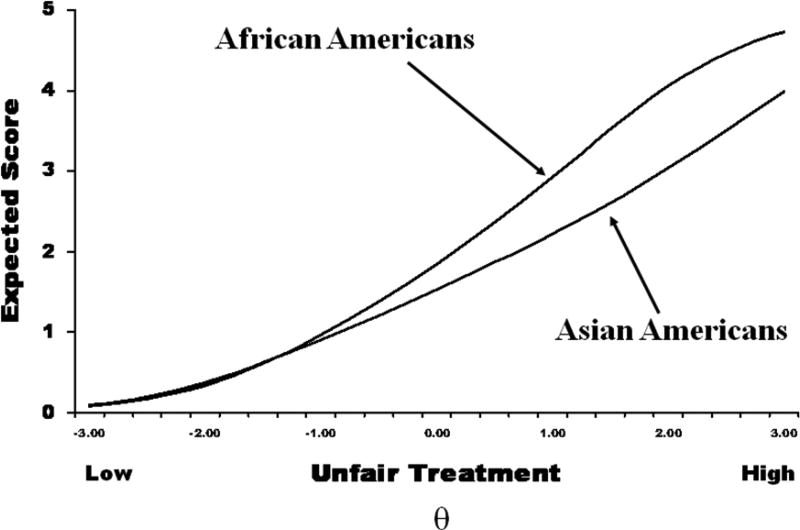

Item #4 (“People act as if they think you are not smart”) also revealed significant DIF between African Americans and Asian Americans (χ2(5) = 80.8) and between Latinos and Asian Americans (χ2(5) = 42.3). This finding was a departure from the cognitive testing, where there was no evidence that the item functioned dissimilarly across groups. Figure 3 presents the expected IRT score curves for African Americans and Asian Americans, showing the expected score on the item “people act as if they think you are not smart” conditional on their level of reported unfair treatment. A score of 0 on the y-axis corresponds to a response of “never”, a score of 1 corresponds to a response of “less than once a year,” and at the upper end, a score of 5 corresponding to the response of “almost every day.” At low levels of overall discrimination, there are no differences between Asian and African Americans, but at moderate and high levels of overall discrimination (as determined by full-scale scores), African Americans are more likely than Asian Americans to report experiences of “people acting as if they think you are not smart.”

Figure 3.

IRT expected score curves for African-Americans and Asian-Americans for the item “people act as if they think you are not smart.”

Item #8 (“You are called names or insulted”) also showed significant non-uniform DIF between African Americans and Asian Americans (χ2(5) = 98.4). African Americans have a higher expected score on this item when overall unfair treatment was high. Asian Americans on the other hand had a higher expected score when overall unfair treatment is at middle to low levels.

Discussion

This study suggests the potential value – and challenges presented -- of using both qualitative and quantitative methodologies to evaluate and refine a questionnaire measuring a latent concept across a multi-ethnic/race sample. In some cases the qualitative and quantitative methods appeared to buttress one another: In particular, both methods were useful in identifying areas where items were redundant (e.g., “courtesy” and “respect”), or needed clarification. Further evidence for convergence was seen for the EDS item “You receive poorer service than other people at restaurants or stores,” which was viewed as problematic by cognitive testing subjects, and was revealed through psychometric analysis to provide relatively little information for determining a person’s experience of discrimination.

Of possibly greater significance, however, were cases when the methods appeared to identify different problems, or even to suggest divergent questionnaire design approaches. A key difference between the methods concerns their utility in assessing scale precision. Cognitive interviewing provides no direct way to assess the variation in reliability as it relates to measuring different levels of discrimination. However, IRT analysis revealed the EDS to be a reliable measure for estimating scores for people who experienced moderate to high amounts of unfair treatment. This suggests that greater effort needs to be made when refining the scale to create items that capture minor acts of unfair treatment, or to revise the response categories to capture more rare events. We believe the response categories suggested through cognitive testing (e.g., ‘rarely’) may help in this regard, so that a problem identified via one method may be resolved through an intervention suggested otherwise, by the other method.

An example of the ways in which qualitative and quantitative methods provided fundamentally different direction with respect to what seems like the same issue was in relation to the use of reference period. Cognitive interviewing indicated that the EDS scale appeared to function best when it used a relatively short, explicit, 12-month reference period. On the other hand, quantitative analysis revealed that very few people reported experiencing these unfair acts on a frequent basis. Hence, one might conclude that a revised survey should rely on a long-term recall period, as a better metric for capturing more rare events of discrimination experience – perhaps the response option of ‘ever.’

This contradiction may reflect the differing emphases of qualitative and quantitative methods, and more generally, the existence of a tension between respondent capacity and data requirements. Cognitive interviewing tends to focus on what appears to be best processed by respondents (e.g., shorter reference periods); whereas quantitative methods are concerned with the instrument’s ability to measure different levels of discrimination among the individuals participating in the study. Thus, findings from each method answer different questions about the instrument. The scale developer is then left with the task of combining these pieces of information and making a judgment about how to refine the questionnaire to address these deficiencies in the current measure. For the currently evaluated scale, we have suggested selecting a shorter reference period such as “past 12 months” (to address the findings from the cognitive interview), and also substituting subjective response categories such as ‘Never’, ‘Rarely’, ‘Sometimes’, and ‘Often’ (to address the quantitative findings). Whether such changes will improve the ability of the scale to better differentiate among respondents in the same population used for this study will require collection of new data from the population on the refined questionnaire.

A further departure between qualitative and quantitative methods concerned the finding that DIF analyses captured potential racial/ethnic bias for a few items, where cognitive interviewing failed to identify such variance. Most notably, DIF was found for the item “people act as if they think you are not smart” between African Americans and Asian Americans and between Latinos and Asian Americans; and DIF was also found for the item “you are called names or insulted” between African Americans and Asian Americans. Neither of these findings was reflected in the cognitive testing results, and it is unlikely that cognitive interviewing can serve as a sensitive measure of DIF on an item-specific level, with the small samples generally tested‥

Conclusion

The major issue addressed in this methodological investigation concerns the relative efficacy of conducting a mixed-method approach to instrument evaluation. This issue begs the question: Was the combination of qualitative and quantitative methods warranted? We make the following conclusions:

In sum, qualitative methods have the advantage of flexibility for in-depth analysis, but findings cannot be generalized to the target population. For example, interviewers were able to assess participants’ understanding and preference related to different response option formats and different recall periods. In contrast, quantitative methods are constrained to the data that are collected, but results are more generalizable (assuming random sampling of participants). For example, DIF testing identified items that may potentially bias scores on the EDS when comparing across racial/ethnic groups. Identifying such issues is much more challenging with cognitive testing methods.

Due to their intrinsic differences, qualitative and quantitative methods sometimes revealed fundamentally different types of information on the adequacy of the survey for the study population of interest. Cognitive testing focused on interpretation and comprehension issues. Psychometric testing was focused on how well the questions in the scale are able to differentiate among respondents who experience different levels of discrimination. Thus, combining the methods can presumably serve to create multiple “sieves”, such that each method located problems the other had missed.

Both methods also identified similar problems within the questionnaire such as the redundancy between the “courtesy” and “respect” items and the poor performance of the item on “You receive poorer service than other people at restaurants or stores.” This consistent finding between methods was reassuring and reinforced the need to address these problems for the next version of the evaluated questionnaire.

Considering optimal ordering of qualitative and quantitative methods for questionnaire evaluation, this study used available secondary data to allow quantitative testing in parallel with cognitive testing with a new sample. For newly developed questionnaires, quantitative analyses of pilot data will normally follow cognitive interviewing. In such cases, evaluation may follow a cascading approach, in which changes are first made based on cognitive testing results, and then the new version is evaluated via quantitative-psychometric methods. Cognitive testing could as well follow quantitative testing, to address additional problems identified by the psychometric analyses (e.g., following DIF testing results).

As a caveat, the existing study represents a case study in the combined use of qualitative and quantitative methods, employing one of a number of possible approaches, and relying on a single instrument. It is likely that the results would differ for studies using somewhat different method variants and instruments. However, the information gained from this mixed-methods study should shed light on issues that should be considered by developers for selecting pretesting and evaluation methods.

Footnotes

This project was part of a larger effort led by the National Cancer Institute to develop a valid and reliable racial/ethnic discrimination module for the California Health Interview Survey (CHIS) (Shariff-Marco et al. 2009).

Racial/Ethnic group used in this scale was determined through respondent self-identification, in response to a previous item.

Note that the term “discrimination” in IRT refers to an item’s ability to differentiate among people at different levels of the underlying construct measured by the scale. This IRT term should not be confused with the construct we are measuring in this study (i.e., perceived racial/ethnic discrimination).

References

- Alegria M, Takeuchi DT, Canino G, Duan N, Shrout P, Meng X. Considering context, place, and culture: The National Latino and Asian American Study. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13(4):208–220. doi: 10.1002/mpr.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegria M, Vila D, Woo M, Canino G, Takeuchi D, Vera M, Febo V, Guarnaccia P, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Shrout P. Cultural relevance and equivalence in the NLAAS instrument: integrating etic and emic in the development of cross-cultural measures for a psychiatric epidemiology and services study of Latinos. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13(4):270–288. doi: 10.1002/mpr.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakura T, Gee GC, Nakayama K, Niwa S. Returning to the “Homeland”: work-related ethnic discrimination and the health of Japanese Brazilians in Japan. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(4):1–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.117309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard R. Social research methods: Qualitative and Quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- De Vogli R, Ferrie JE, Chandola T, Kivimäki M, Marmot MG. Unfairness and health: evidence from the Whitehall II Study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2007;61:513–518. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.052563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Walsemann K. Does health predict the reporting of racial discrimination or do reports of discrimination predict health? Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Youth. Social Science and Medicine. 2009;68:1676–1684. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heerenga S, Warner J, Torres M, Duan N, Adams T, Berglund P. Sample designs and sampling methods for the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;10(4):221–240. doi: 10.1002/mpr.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunte H, Williams DR. The association between perceived discrimination and obesity in a population based multiracial/ethnic adult sample. American Journal of Public Health. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.128090. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabine TB, Straf ML, Tanur JM, Tourangeau R, editors. Cognitive aspects of survey methodology: Building a bridge between disciplines. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie AJ. Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher. 2004;33(7):14–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40(3):208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis TT, Everson-Rose SA, Powell LH, Mathews KA, Brown C, Karavolos K. Chronic exposure to everyday discrimination and coronary artery calcification in African-American women: the SWAN Heart Study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2006;68(3):362–368. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000221360.94700.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller K, Mont D, Maitland A, Altman B, Madans J. Results of a cross-national structured cognitive interviewing protocol to test measures of disability. Quality and Quantity (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric Theory. 3. McGraw-Hill, Inc.; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Panter AT, Daye CE, Allen WR, Wightman LF, Deo M. Everyday discrimination in a national sample of incoming law students. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education. 2008;1(2):67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Pavalko E, Mossakowski KN, Hamilton VJ. Does perceived discrimination affect health? Longitudinal relationships between work discrimination and women’s physical and emotional health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44:18–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennell B-E, Bowers A, Carr D, Chardoul S, Cheung G-Q, Dinkelmann K, Gebler N, Hansen SE, Pennell S, Torres M. The development and implementation of the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, The National Survey of American Life, and the National Latino and Asian American Survey. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13(4):241–269. doi: 10.1002/mpr.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presser S, Couper MP, Lessler JT, Martin E, Rothgeb JM, Singer E. Methods for testing and evaluating survey questions. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2004;68:109–130. [Google Scholar]

- Samejima F. Estimation of latent ability using a response pattern of graded scores. Psychometrika Monographs. 1969;(17) [Google Scholar]

- Shariff-Marco S, Gee GC, Breen N, Willis G, Reeve BB, Grant D, Ponce NA, Krieger N, Landrine H, Williams DR, Alegria M, Mays VM, Johnson TP, Brown ER. A mixed-methods approach to developing a self-reported racial/ethnic discrimination measure for use in multiethnic health surveys. Ethnicity & Disease. 2009;19:447–453. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashakkori A, Teddlie C. Mixed Methodology: Combining qualitative and quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Thissen D, Steinberg L, Wainer H. Detection of differential item functioning using the parameters of item response models. In: Holland PW, Wainer H, editors. Differential Item Functioning. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1993. pp. 67–113. [Google Scholar]

- Thissen D, Nelson L, Rosa K, McLeod LD. Item response theory for items scored in more than two categories. In: Thissen D, Wainer H, editors. Test Scoring. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001. pp. 141–186. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, González HM, Williams S, Mohammed SA, Moomal H, Stein DJ. Perceived discrimination, race and health in South Africa: Findings from the South Africa Stress and Health Study. Social Science and Medicine. 2008;67(3):441–52. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Spencer MS, Jackson JS Race, stress and physical health: The role of group identity. In: Self and Identity: Fundamental Issues. Contrada RJ, Ashmore RD, editors. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999. pp. 71–100. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32:20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology. 1997;2(3):335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis G. Cognitive Interviewing: A Tool for Improving Questionnaire Design. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005. [Google Scholar]