Introduction

General pustular psoriasis (GPP) is a rare form of psoriasis and is clinically characterized by widespread eruptions of sterile pustules and bright erythematous skin accompanied by periods of fever, chills, rigors, neutrophilia, and elevated serum C-reactive protein.1 Acrodermatitis of Hallopeau, palmoplantar psoriasis pustulosis, and annular pustular psoriasis may be variations of this GPP.2 In 2011, Marrakchi et al3 reported a subgroup of GPP patients with a specific genetic defect: a deficiency of interleukin-36 receptor antagonist (DITRA). We report a case of juvenile DITRA successfully treated with acitretin in combination with etanercept.

Case report

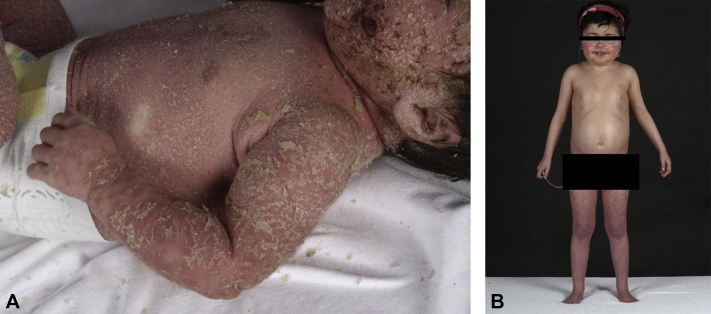

We present a case of a child that was referred to us at the age of 2 months. She was the first child of 2 consanguineous Moroccan parents. No complications were reported during pregnancy or delivery (gestational age at delivery was 41 weeks and 6 days). There was no family history of psoriasis. The first week postpartum, multiple pustules appeared in the perioral and diaper area. At the age of 7 weeks, an erythroderma developed with macerations in the folds (Fig 1, A). Zinc level, complement-5, and lymphocyte subsets were normal. Chest radiograph was normal, and no hair or nail abnormalities were found. A diagnosis of juvenile seborrheic dermatitis was made at that time, and she was treated with topical steroids with a good response.

Fig 1.

A, Erythroderma presented at age 7 weeks. B, DITRA with 6 months treatment with etanercept and acitretin, age 4 years and 3 months.

In the following months, she had recurrent episodes of erythroderma, fever, vomiting, failure to thrive, leukocytosis, and elevated acute-phase protein levels. At 6 months, she was admitted to the hospital for diarrhea and imminent dehydration. Palmoplantar confluent pustules were seen, suspect for pediatric acral pustulosis or pustular psoriasis. Topical steroids were sufficient to stabilize the disease. The next months were complicated by dehydration caused by a norovirus infection (age 8 months), and adrenocortical insufficiency (age 10 months) possibly caused by the topical steroids. At 14 months, little improvement was seen using coal tar 5% in vaseline-lanette cream and mometasone ointment 2 to 3 times per week.

At 17 months, the clinical picture changed with generalized pustules including scalp, palms, and soles. A skin biopsy found parakeratosis and pustules containing neutrophils, supporting a diagnosis of psoriasis pustulosa. Around this time, the first publications of DITRA (online Mendelian inheritance in man [OMIM] #614204) appeared3 and Sanger sequence analysis of the IL36RN gene found a homozygous mutation, c.80T>C (p.Leu27Pro), confirming the diagnosis of DITRA at 18 months of age.

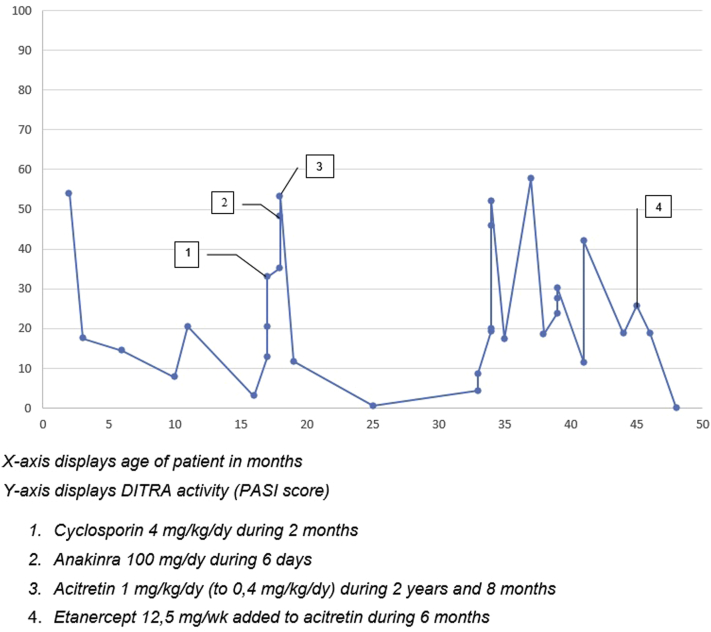

During the course of her disease, multiple systemic therapies were administered with different outcomes as illustrated by the PASI (Psoriasis Activation and Severity Index) scores (mean, 24.0; range, 0.7-57.6) assessed at different time points and based on clinical presentation (Fig 2). Cyclosporin (4 mg/kg/d for 2 months) induced increase of erythema and pustules. With anakinra (5 mg/kg/d for 6 days) the pustules initially disappeared, but within 6 days there was a flare and persistent erythema. Acitretin was given for 2 years and 8 months at an initial dose scheme according to Chao et al4 (initially 1 mg/kg/d) and showed initially a good response with a PASI score of 0.7.4 During the following relapses and remissions, the acitretin dose varied between 0.4 mg/kg/d and 1 mg/kg/d. Etanercept (12.5 mg/wk) was added to acitretin with a good response for 6 months, even reaching a PASI score of 0.0 after the fifth injection of etanercept (see Fig 2). After 6 months, good improvement is seen with acitretin, 15 mg/d, and etanercept 12.5 mg/wk (Fig 1, B). No side effects were noticed by clinicians or reported by the parents.

Fig 2.

PASI scores of our patient during different treatments.

Discussion

Deficiency of DITRA is a subgroup of GPP patients with a specific monogenetic defect3 that is difficult to treat. Recommendations for first- and second-line therapies in GPP patients are made in cooperation with the Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation.5 In children, first-line therapies include acitretin, cyclosporin, methotrexate, and etanercept, and second line therapies include adalimumab, infliximab, and ultraviolet B phototherapy.5 There are no guidelines for the treatment of DITRA, and most cases presented in literature with therapeutic outcomes are derived from case reports and case series, reflecting the extreme rarity of the disorder. Follow-up periods in these patients, when mentioned, have been limited. This case illustrates a patient with juvenile DITRA, showing response to different systemic therapies and reporting an initially successful treatment with acitretin and a good response to acitretin combined with etanercept after a relapse.

Since the discovery of DITRA in 2011, fewer than 15 juvenile patients with DITRA and corresponding therapeutic outcomes were documented. The mutation c.80T>C/p.Leu27Pro in our case is identical to that originally described by Marrakchi et al in 20113 and was only described twice after (Table I). One described by Rossi-Semerano et al7 was successfully treated with anakinra (2-4 mg/kg/d for 2 months).7 However, in the case described by Carapito et al,6 treatment with anakinra (5 mg/kg/d for 3 months) was not successful. In our patient, anakinra in a similar dose (100 mg/d), had to be stopped after 6 days because of a flare of the disease. Recent treatment of juvenile DITRA (C115+6T>C/p.Arg10ArgfsX1) with tumor necrosis factor-α blockers (infliximab) was reported to be successful8 and unsuccessful.9 Similar treatments in patients with identical mutations result in different outcomes, illustrating the complexity of the disease and its treatment. A recent publication showed a possible correlation between disease severity in DITRA, mutation of the IL36RN gene, and IL36RN protein expression.10 Null mutations with complete absence of IL36RN antagonist (eg, c.80T>C/p.Leu27Pro) were associated with severe clinical phenotypes compared with mutations with decreased or unchanged protein expression.10 As mentioned, little is known about the treatment in DITRA, and treatment response is difficult to monitor, because DITRA by its nature is characterized by remissions and flares. DITRA patients can lose response to therapy, even after prolonged use, as is seen in our case with acitretin as monotherapy. Although the therapy with acitretin and etanercept looks promising within 6 months, diminished therapy effect is still possible.

Table I.

Therapy outcomes in juvenile patients with c.80T>C/p.Leu27Pro mutation

| Study | Age | Sex | Final treatment | Duration | Response | Outcome details | Previous treatment(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Carapito et al6 | 8 mo | M | Anakinra | 3 mo | None | — | Canakinumab |

| 2 | Rossi-Semerano et al7 | 6 wk | M | Anakinra | 2 mo | Good | Recovery after 8 days, no flares after 2 months | — |

| 3 | Current case | 3 y | F | Acitretin + etanercept | 6 mo | Good | — | Cyclosporin, topical steroids, anakinra, acitretin |

Conclusion

DITRA is a recently described variation of GPP. Little is known about treatment regimes. Our case of juvenile DITRA describes a good effect of acitretin in combination with etanercept for 6 months. Further research is necessary about optimal treatment for DITRA in relation to mutation status.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Iizuka H., Takahashi H., Ishida-Yamamoto A. Pathophysiology of generalized pustular psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2003;295(Suppl 1):S55–S59. doi: 10.1007/s00403-002-0372-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Setta-Kaffetzi N., Navarini A.A., Patel V.M. Rare pathogenic variants in IL36RN underlie a spectrum of psoriasis-associated pustular phenotypes. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:1366–1369. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marrakchi S., Guigue P., Renshaw B.R. Interleukin-36-receptor antagonist deficiency and generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:620–628. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chao P.H., Cheng Y.W., Chung M.Y. Generalized pustular psoriasis in a 6-week-old infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:352–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2009.00918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robinson A., Van Voorhees A.S., Hsu S. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carapito R., Isidor B., Guerouaz N. Homozygous IL36RN mutation and NSD1 duplication in a patient with severe pustular psoriasis and symptoms unrelated to deficiency of interleukin-36 receptor antagonist. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:302–305. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rossi-Semerano L., Piram M., Chiaverini C. First clinical description of an infant with interleukin-36-receptor antagonist deficiency successfully treated with anakinra. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e1043–e1047. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan J., Qiu L., Xiao T., Chen H.D. Juvenile generalized psoriasis with IL36RN mutation treated with short-term infliximab. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29:164–167. doi: 10.1111/dth.12325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song H.S., Yun S.J., Park S. Gene mutation analysis in a korean patient with early-onset and recalcitrant generalized pustular psoriasis. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:424–425. doi: 10.5021/ad.2014.26.3.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tauber M., Bal E., Pei X.Y. IL36RN mutations affect protein expression and function: a basis for genotype-phenotype correlation in pustular diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136(9):1811–1819. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]