Abstract

Obesity and adiponectin depletion have been associated with the occurrence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). The goal of this study was to identify the relationship between weight gain, adiponectin signaling, and development of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) in an obese, diabetic mouse model. Leptin-receptor deficient (Leprdb/db) and C57BL/6 mice were administered a diet high in unsaturated fat (HF) (61%) or normal chow for 5 or 10 weeks. Liver histology was evaluated using steatosis, inflammation, and ballooning scores. Serum, adipose tissue, and liver were analyzed for changes in metabolic parameters, messenger RNA (mRNA), and protein levels. Leprdb/db HF mice developed marked obesity, hepatic steatosis, and more than 50% progressed to NASH at each timepoint. Serum adiponectin level demonstrated a strong inverse relationship with body mass (r = −0.82; P < 0.0001) and adiponectin level was an independent predictor of NASH (13.6 μg/mL; P < 0.05; area under the receiver operating curve (AUROC) = 0.84). White adipose tissue of NASH mice was characterized by increased expression of genes linked to oxidative stress, macrophage infiltration, reduced adiponectin, and impaired lipid metabolism. HF lepr db/db NASH mice exhibited diminished hepatic adiponectin signaling evidenced by reduced levels of adiponectin receptor-2, inactivation of adenosine monophosphate activated protein kinase (AMPK), and decreased expression of genes involved in mitochondrial biogenesis and β-oxidation (Cox4, Nrf1, Pgc1α, Pgc1β and Tfam). In contrast, recombinant adiponectin administration up-regulated the expression of mitochondrial genes in AML-12 hepatocytes, with or without lipid-loading.

Conclusion

Leprdb/db mice fed a diet high in unsaturated fat develop weight gain and NASH through adiponectin depletion, which is associated with adipose tissue inflammation and hepatic mitochondrial dysfunction. We propose that this murine model of NASH may provide novel insights into the mechanism for development of human NASH.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common liver disease in the United States. It encompasses a wide spectrum of liver diseases ranging from benign steatosis to pathological nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which can progress to cirrhosis and liver cancer.1 Although obesity and insulin resistance are major risk factors for NAFLD, the molecular mechanisms underlying the progression of this disease from simple steatosis to clinical NASH remain unclear.2

A commonly observed effect of increased weight gain and expansion of visceral fat is a decrease in the adipose tissue-specific hormone, adiponectin.3,4 Depletion of this antiinflammatory and antidiabetic adipokine has been linked to the progression of NASH.5 While many small-animal models of NASH have been created by high-caloric feeding of saturated6–10 or unsaturated fats,11–16 as well as through a combination of dietary and genetic factors,7,19–21 the direct effects of weight gain on adiponectin depletion and NASH development have not been demonstrated in an animal model. Furthermore, in vivo and in vitro studies have demonstrated that saturated fats have other unique obesity-independent effects in the liver such as inflammation,22 endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress,23 altered insulin signaling,24 and increased apoptosis.25 Thus, the effects of saturated fats and other common dietary components such as fructose6,26 and cholesterol6,27,28 which also have similar independent effects could confound an understanding of the relationship between weight gain, adiponetin signaling, and NASH. Comparatively, unsaturated fats are often demonstrated to have ameliorating effects in liver injury, especially monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) and omega (ω)-3 fatty acids.29 In contrast, ω-6 fatty acids have been found to be detrimental or at least not beneficial,29 and several studies suggest that a diet composed of a high ω-6 to ω-329,30 ratio may represent a frequently disregarded route to the development of NASH.

Other challenges in the development of small-animal models of NASH are consistency of feeding and the ability to reliably produce extensive weight gain in a suitable time period. Several models centered on high-fat diet consumption have failed to produce substantial weight gain8,10,13,15–17 and exhibit infrequent NASH development,8,16,17 while other models required over 20 weeks to develop the desired weight gain and histologic features.6,9,19 A more elegant solution to consistent weight gain with minimal intervention is the use of hyperphagic mice, such as leptin- and leptin receptor-deficient mice (Lepob/ob and Leprdb/db, respectively) as increases in leptin signaling have previously been linked to adaptive feeding.31

The goal of the current study was to determine the role of adiponectin depletion in the development of NASH using a murine model which recapitulates the human NASH metabolic profile characterized by insulin resistance, diabetes, and obesity and the histological features similar to human NASH such as inflammation, hepatocellular ballooning, and apoptosis by feeding a high-unsaturated fat diet to Leprdb/db mice and to corroborate the direct effects of adiponectin in AML-12 hepatocytes in the presence or absence of free-fatty acids.

Materials and Methods

Animals Studies

Five-week-old male C57BL/6J and B6.BKS(D)-Leprdb/J diabetic mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were fed a normal chow diet (N) or a liquid high-fat diet (HF) (#712031, Lieber DeCarli Diet, Dyets, Bethlehem, PA; 71% energy from fat, 18% from protein, and 11% from carbohydrates; 1 Kcal/mL) ad libitum for either 5 or 10 weeks. Mice were weighed weekly and food consumption was monitored daily for mice on the HF diet. At the 5- and 10-week endpoints, fasting mice were sacrificed and serum and plasma samples were collected by cardiac puncture for assays of glucose, liver enzymes, and cytokines. All animal protocols were approved by the Benaroya Research Institute Animal Care and Use Committee.

Histological Analysis of Liver Tissue

Left and medial lobes of liver tissues were fixed in 10% formaldehyde saline solution and stained with hematoxylineosin and Masson’s trichrome to assess fibrosis. Histological scoring was performed by a blinded hepatopathologist (M.M.Y.) with expertise in steatohepatitis by evaluating steatosis (0–3), inflammation (0–3), ballooning (0–2), and fibrosis (0–6) scores after the NASH Clinical Research Network (CRN) scoring system.32

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis for group comparisons was performed using Kruskal-Wallis, Mann Whitney, and Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Statistics were performed using the Pearson correlation test for continuous variables and the Spearman rank correlation for ordinal variables to determine associations. All analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (La Jolla, CA) and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

See the Supporting Materials for a description of additional methods and results.

Results

Leprdb/db Mice Fed an Unsaturated Fat Diet Develop Marked Obesity and Hepatomegaly

Weight gain was assessed weekly in C57BL/6 and Leprdb/db mice. Mean HF diet consumption by Leprdb/db HF-fed mice was ~27 Kcal/day for the first 4 weeks, but ~23 Kcal/day for the final 6 weeks. This was significantly increased relative to C57BL/6 HF mice who consumed ~6.5 Kcal/day during most of the study period (P < 0.001, Fig. 1A).

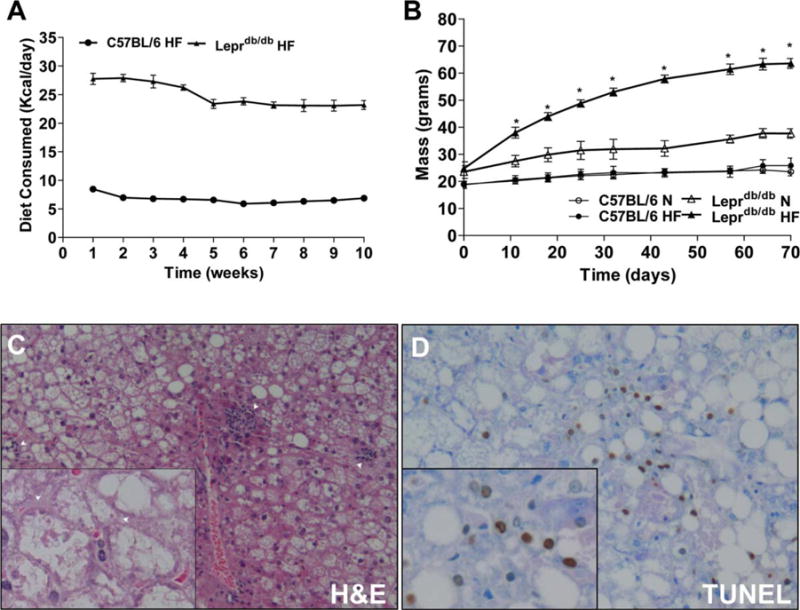

Fig. 1.

HF-fed Leprdb/db mice experience rapid weight gain, advanced NASH histology, and increased TUNEL staining. (A,B) Leprdb/db and C57BL/6 mice were put on a chow and HF diet and assessed weekly for food consumption and weight gain. (C) Representative micrograph of a Leprdb/db mouse on HF diet, showing hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining (C, 200× and 400×) and apoptosis by way of TUNEL staining (D, 200× and 400×). Arrows in (C) indicates lobular inflammation (200×), and ballooned hepatocytes (400×). *P < 0.05 versus Leprdb/db N Leprdb/db, leptin-receptor deficient; N, normal chow diet; HF, high-fat diet; H&E, hematoxylineosin; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling.

Leprdb/db HF mice rapidly increased in mass at a rate of ~5.5 g/week for the first 5 weeks and ~1.5 g/week for the remainder of the study, with average mass ~62 g by week 8. Chow-fed Leprdb/db (N) mice increased in mass at ~1.5 g/week for the entire study and gained ~60% of their starting mass after 10 weeks (35–40 g final mass). C57BL/6 N and HF mice showed nearly identical weight gain at ~0.5 g/week throughout, with HF mice showing a slight increase only in the final week. Leprdb/db HF mice had significantly increased mass at every timepoint compared to Leprdb/db N mice while no differences were observed in body mass between C57BL/6 groups after 70 days (Fig. 1B). Liver mass was not significantly increased by HF feeding in C57BL/6 mice. Leprdb/db N mice had increased liver mass compared to C57BL/6 N mice at both timepoints, while Leprdb/db HF mice had hepatomegaly compared to genetic and dietary controls (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effects of Diet and Genotype on Weight Gain and Metabolic Parameters After 5 and 10 Weeks of Dietary Administration

| Time on Diet Genotype Diet |

5 weeks

|

10 weeks

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C57BL/6

|

Leprdb/db

|

C57BL/6

|

Leprdb/db

|

|||||

| Chow (n=6) | High fat (n=6) | Chow (n=6) | High fat (n=5) | Chow (n=6) | High fat (n=6) | Chow (n=6) | High fat (n=6) | |

| Weight gain | ||||||||

| Body mass, g | 23.5 ± 0.2 | 24.8 ± 0.6 | 32.6 ± 1.8 | 54.4 ± 0.7*† | 23.5 ± 0.6 | 25.9 ± 1.1 | 37.7 ± 0.7 | 63.6 ± 0.7*† |

| Liver mass, g | 1.07 ± 0.03 | 1.06 ± 0.04 | 1.42 ± 0.14† | 2.88 ± 0.07*† | 1.07 ± 0.02 | 0.98 ± 0.04 | 1.99 ± 0.25† | 2.92 ± 0.20*† |

| Metabolic parameters | ||||||||

| ALT, U/L | 20.4 ± 1.9 | 38.8 ± 9.5 | 50.8 ± 4.5† | 245.8 ± 1.6*† | 48 ± 10.7 | 128.7 ± 58.3 | 96.8 ± 18.1 | 244.7 ± 29.9*† |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 356 ± 19 | 464 ± 30 | 747 ± 45† | 718 ± 51† | 429 ± 53 | 483 ± 17 | 828 ± 52† | 699 ± 75† |

| Insulin, pg/mL | 415 ± 37 | 426 ± 70 | 2846 ± 631† | 2333 ± 452† | 200 ± 22 | 236 ± 67 | 3147 ± 910† | 3189 ± 372† |

| TNFα, pg/mL | 7.5 ± 0.4 | 8.6 ± 0.2 | 7.2 ± 1.0 | 10.5 ± 0.8 | 6.1 ± 0.4 | 7.9 ± 0.6 | 8.9 ± 0.8† | 10.5 ± 0.6† |

| IL-6, pg/mL | 5.4 ± 1.2 | 8.2 ± 1.5 | 11.9 ± 3.6 | 25.1 ± 7.0 | 4.8 ± 1.4 | 5.6 ± 0.8 | 12.3 ± 2.1† | 14.1 ± 2.0† |

| Leptin, ng/mL | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 7.7 ± 1.0* | 50.3 ± 16.7† | 319.2 ± 71.1*† | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 8.2 ± 2.5* | 83.4 ± 21.4† | 274.1 ± 104.4*† |

| Adiponectin, μg/mL | 19.4 ± 0.7 | 18.8 ± 0.3 | 18.2 ± 0.4 | 13.7 ± 0.6*† | 18.4 ± 0.4 | 18.5 ± 0.9 | 18.2 ± 1.2 | 12.2 ± 0.8*† |

Mean body mass, liver mass, alanine transaminase (ALT), glucose, insulin, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), interleukin-6 (IL-6), leptin and adiponectin. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM.

P < 0.05 vs. chow control;

P < 0.05 vs. C57BL/6 control.

HF-Fed Leprdb/db Mice Recapitulate the NASH Metabolic Phenotype

A panel of serum markers was examined to analyze liver injury, inflammation, and adipose tissue function (Table 1). Liver injury as determined by serum alanine transaminase (ALT) levels was not increased in C57BL/6 HF mice at either timepoint (Table 1). Leprdb/db HF mice showed greatly increased ALT levels at both timepoints compared to dietary and genetic controls. Glucose and insulin levels were substantially increased in all Leprdb/db mice compared to C57BL/6 controls, but showed no changes between chow and HF-fed animals within the C57BL/6 and Leprdb/db strains. Serum levels of the inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) and interleukin (IL)-6 were both increased in Leprdb/db N and HF mice by 10 weeks compared to their C57BL/6 dietary controls but not significantly elevated in Leprdb/db HF mice compared to Leprdb/db N. As expected, serum leptin was substantially elevated in all Leprdb/db mice compared to C57BL/6 controls. In both C57BL/6 and Leprdb/db animals, an HF diet sig nificantly increased leptin levels compared to chow-fed controls. Adiponectin levels were not significantly altered in C57BL/6 HF or Leprdb/db N mice compared to C57BL/6 N controls; however, Leprdb/db HF mice experienced ~25% and 33% reductions in adiponectin compared to Leprdb/db N mice at the 5 and 10 week timepoints, respectively.

Development of Obesity Results in NASH Histology and Increased Hepatic Apoptosis

Histological scoring for features of steatohepatitis were assessed as described in the Materials and Methods32 and is shown in Table 2. C57BL/6 N and HF mice showed minimal histological activity with no steatosis at either timepoint. One Leprdb/db N mouse developed mild steatosis at 5 weeks, while two had mild steatosis by 10 weeks. In contrast, Leprdb/db HF mice developed moderate to severe steatosis with increased lobular inflammation and hepatocellular ballooning at both 5 and 10 weeks (50%, 60%, respectively, Fig. 1C; Supporting Fig. 1). Apoptotic nuclei were very infrequently observed in C57BL/6 N and HF mice with minor increases observed in Leprdb/db N mice. However, at both 5 and 10 weeks Leprdb/db HF mice exhibited increased apoptosis by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining (Fig. 1D) compared to C57BL/6 HF and Leprdb/db N controls.

Table 2.

Effects of Diet and Genotype on Liver Injury After 5 and 10 Weeks of Dietary Administration

| Time on Diet Genotype Diet |

5 weeks

|

10 weeks

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C57BL/6

|

Leprdb/db

|

C57BL/6

|

Leprdb/db

|

|||||

| Chow (n=6) | High fat (n=6) | Chow (n=6) | High fat (n=5) | Chow (n=6) | High fat (n=6) | Chow (n=6) | High fat (n=6) | |

| Steatosis | 0 | 0 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.3*† | 0 | 0 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.2*† |

| Inflammation | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 1 ± 0*† | 0 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.3*† |

| Ballooning | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.6 ± 0.2*† | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.2 ± 0.3*† |

| NAFLD Dx | 0/6 | 0/6 | 1/6 | 2/5 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 2/6 | 3/6 |

| NASH Dx | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 3/5 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 3/6 |

| TUNEL, % | 0.53 ± 0.05 | 0.50 ± 0.09 | 0.72 ± 0.23 | 2.32 ± 1.01*† | 0.29 ± 0.07 | 0.70 ± 0.24 | 1.30 ± 0.65 | 2.34 ± 0.54*† |

Means scores for steatosis, inflammation, ballooning, and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) with the ratio of mice diagnosed with NAFLD and NASH. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM.

P < 0.05 vs. dietary control;

P < 0.05 vs. strain control.

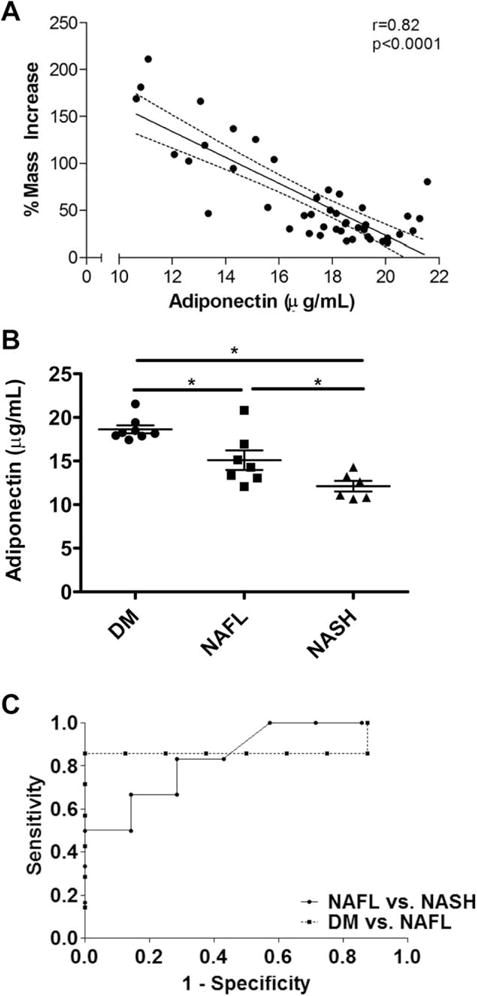

Reduced Serum Adiponectin Levels Are Associated With NASH Diagnosis

Mice with NAFL (n = 8) and NASH (n = 6) at 5 or 10 weeks were compared using Leprdb/db N mice without steatosis as controls as shown in Table 2 (n = 8; denoted as diabetes mellitus, DM). There were no significant differences between serum leptin levels among DM, NAFL, and NASH groups in the Leprdb/db mice. Remarkably, of all parameters tested, only serum adiponectin differentiated the two hepatic phenotypes, NAFL and NASH. Adiponectin levels were significantly lower in NASH compared to NAFLD mice (P = 0.046, Fig. 2B) and correlated strongly to the proportional increase in body mass (r = −0.82, P < 0.0001, Fig. 2A). Furthermore, receiver-operator curve (ROC) analysis using adiponectin levels to predict NASH versus NAFL showed an area under the ROC (AUROC) (95% confidence interval [CI]) of 0.85 (0.63–1.0) (P = 0.038) with an 83.3% sensitivity and 71.4% specificity for adiponectin levels less than 13.29 μg/mL (Fig. 2C). Adiponectin levels were also useful for predicting NAFL versus DM with an AUROC (95% CI) of 0.88 (0.64–1.0) (P < 0.02, Fig. 2C) with a sensitivity of 85.7% and a specificity of 100% for adiponectin levels less than 17.19 μg/mL.

Fig. 2.

Mass increase results in adiponectin depletion and is an independent predictor of NASH. (A) Correlation between serum adiponectin and percent mass increase across all the mice in the study. (B) Serum adiponectin levels in DM, NAFL and NASH mice. *P < 0.05, n = 6–8 each. (C) ROC analysis of serum adiponectin comparing DM, NAFL and NASH groups.

NASH Mice Exhibit Adipose Tissue Inflammation and Impaired Lipid Metabolism

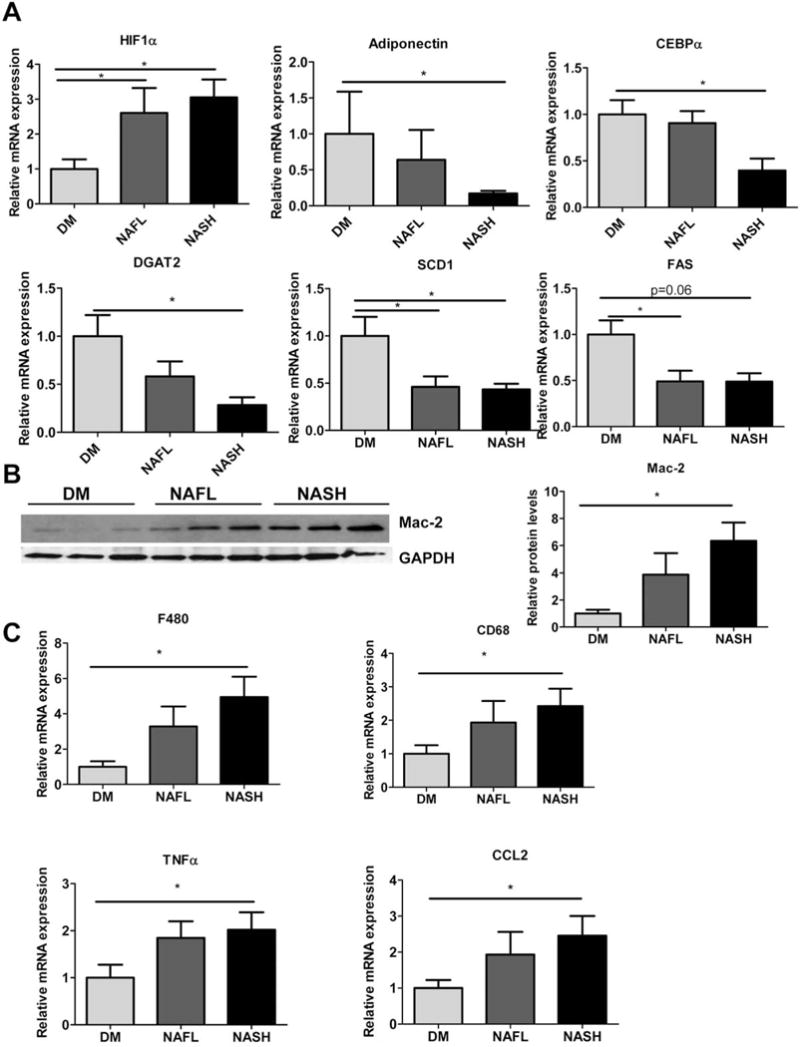

Figure 3A shows relative mRNA levels of differentially expressed genes in the epididymal white adipose tissue (EWAT) of the Leprdb/db diagnosis groups. Adiponectin gene expression (Adipoq) and one of its transcription factors, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha (C/ebpα), were significantly reduced in NASH mice compared to DM mice, explaining the observed differences in serum levels. Triglyceride synthesis enzyme, diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 2 (Dgat2) showed a reduction in NASH mice relative to the DM group. Furthermore, gene expression levels of stearoyl CoA desaturase (Scd1) and fatty acid synthase (Fas) were reduced in the NASH and NAFL groups relative to DM. Expression of hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha (Hif1α) was increased in NAFLD and NASH mice. Erythropoeitin (Epo) gene expression was directly associated with serum adiponectin levels across all Leprdb/db mice (r = 0.49, P < 0.001; data not shown). The protein levels of Mac-2, an activated macrophage marker, was up-regulated in NASH mice (Fig. 3B) as was the expression level of macrophages markers, CD68 and F480/emr1, and cytokines, Ccl2 (also known as MCP-1) and Tnfα in the EWAT of NASH mice (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Adipose tissue dysfunction in NASH mice. (A) Relative mRNA levels of Hif1α, Adipoq, C/ebpα, Dgat2, Scd1 and Fas. (B) Representative blot from adipose tissue lysates of Mac-2 (left) and densitometric quantitation (right) from DM, NAFL and NASH mice. (C) Relative mRNA levels of macrophage markers and inflammatory mediators: F480, CD68, Tnfα and Ccl2 in the adipose tissue of DM, NAFL, and NASH mice. n = 6–8, *P < 0.05.

To further determine potential contributors to the distinct decrease in adiponectin levels observed in NASH mice, inter- (Fig. 2B) and intragroup (Supporting Table 2) regression analyses were performed between Adipoq mRNA and serum adiponectin levels against various genes in the adipose tissue. Interestingly, Adipoq expression showed a strong negative relationship with expression of inflammatory genes Il6 (r = −0.89, P = 0.02) and Crp (r = −0.92, P = 0.01) within the NASH group alone and serum adiponectin levels were inversely correlated with expression of inflammatory genes Nfkb1 (r = −0.92, P = 0.01), Tnfα (r = −0.94, P = 0.005) and directly associated with C/ebpα expression levels (r = 0.95, P = 0.004). There was also a positive association between expression of all these genes and final mass (|r > 0.80|, P < 0.05 for all) in NASH mice, but not within or across the other groups (data not shown).

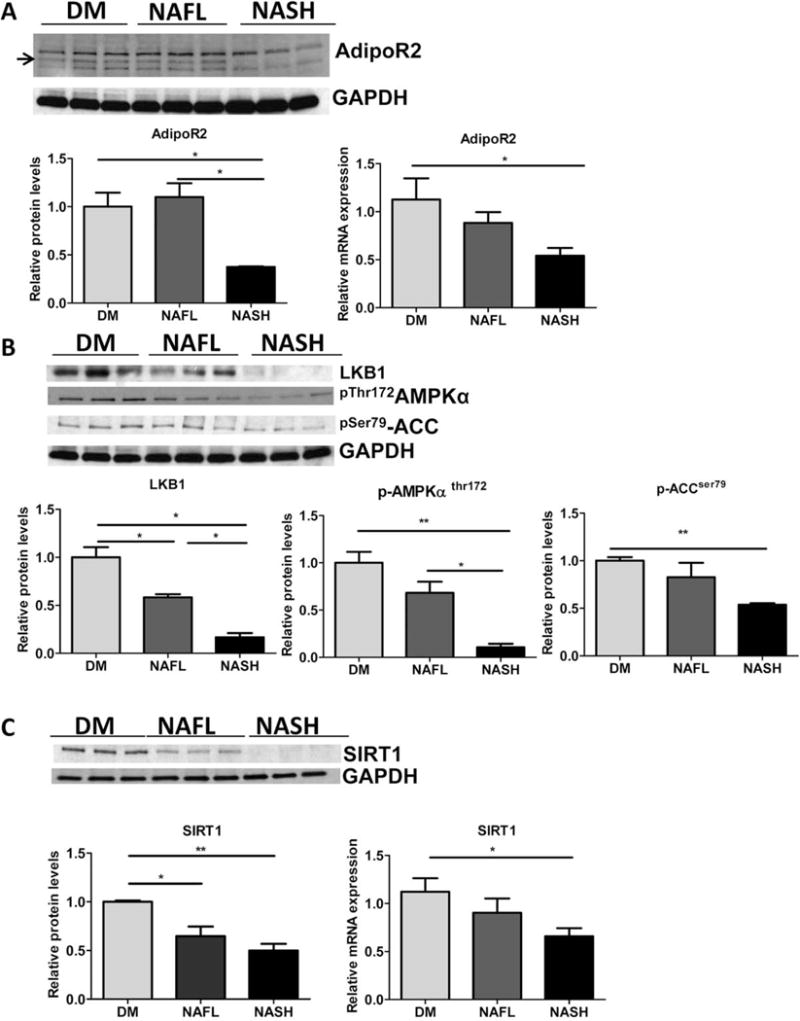

Diminished Hepatic Adiponectin-adipoR2-AMPK Signaling in NASH Mice

To examine the downstream effects of hepatic adiponectin depletion, we evaluated protein and mRNA levels of the predominantly liver-specific adiponectin receptor-2 (AdipoR2)33 and the activation status of its target effector, a serine threonine kinase-adenosine monophosphate activated protein kinase (AMPK) (Fig. 4A–C). The relative levels of AdipoR2 and phosphorylation status of AMPKα were reduced in the livers of NASH mice relative to both DM and NAFL groups (Fig. 4A,B). Protein levels of liver kinase B1 (LKB1), one of the upstream protein kinases responsible for activating AMPK, were also decreased in NASH mice relative to NAFL and DM (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, the phosphorylation of Acetyl CoA carboxylase (ACCα), the downstream target of AMPK, was reduced in NASH mice relative to DM (Fig. 4B). Finally, protein and gene expression levels of sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), a regulator of hepatic energy metabolism, which is regulated by adiponectin and AMPK signaling,34 were also significantly lower in the NASH mice relative DM (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

NASH mice experience decrease in hepatic adiponectin-AMPK signaling. Representative western blots (top) and densitometric quantitations of (A) adiponectin receptor-2 and GAPDH protein and relative mRNA expression analysis (below) (B). Representative western blots (top) and densitometric quantitations of LKB1, phosphorylated (Thr 172)-AMPKα protein levels, phosphorylated (Ser 79)-ACCα relative to GAPDH are shown (below). (C). Representative western blots (top), and densitometric quantitations of SIRT1 relative to GAPDH and relative gene expression in DM, NAFL and NASH groups of mice (below). DM mice (n = 5), NAFL (n = 5), and NASH mice (n = 5), *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 indicates statistical significance between the relevant groups shown.

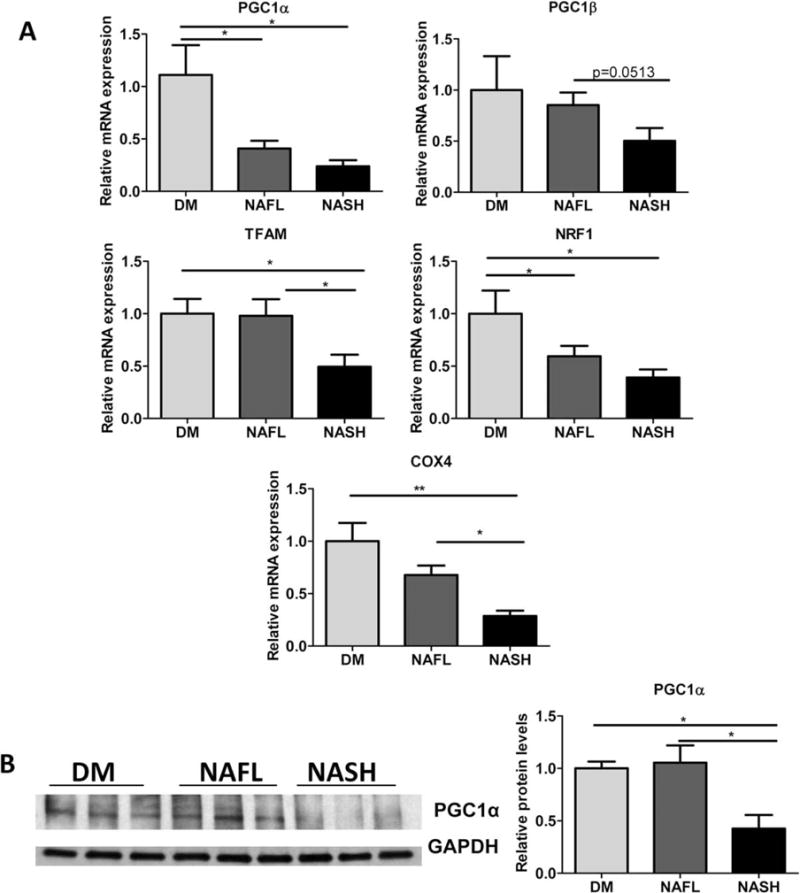

Hepatic Mitochondrial Biogenesis Is Impaired in Livers of NASH Mice

We next examined the status of the mitochondrial biogenesis pathway, since the adiponectin-SIRT1-AMPK axis has been shown previously to influence mitochondrial signaling.35 We found that gene expression levels of a class of important nutrient sensors and transcription factors, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (Pgc1α) and beta (Pgc1β),36 and their downstream mitochondrial genes including Nuclear response factor (Nrf1), Transcription factor A, mitochondrial (Tfam), and cytochrome oxidase 4 (Cox4) were decreased in the NASH mice compared to DM and NAFL groups (Fig. 5A). Protein levels of PGC1α were also significantly reduced in the livers of NASH mice with respect to DM and NAFL mice (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

NASH mice experience hepatic mitochondrial dysfunction relative to DM and NAFL mice. (A) Relative mRNA expression levels of Pgc1α, Pgc1β, Tfam, Nrf1 and Cox4 were determined in DM, NAFL, and NASH mice. n = 6–8, *P < 0.05. (B) Protein levels of PGC1α relative to GAPDH protein (as loading control) were assessed in the livers of DM, NAFL, and NASH groups. n ≥ 5, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 indicates statistical significance between the relevant groups.

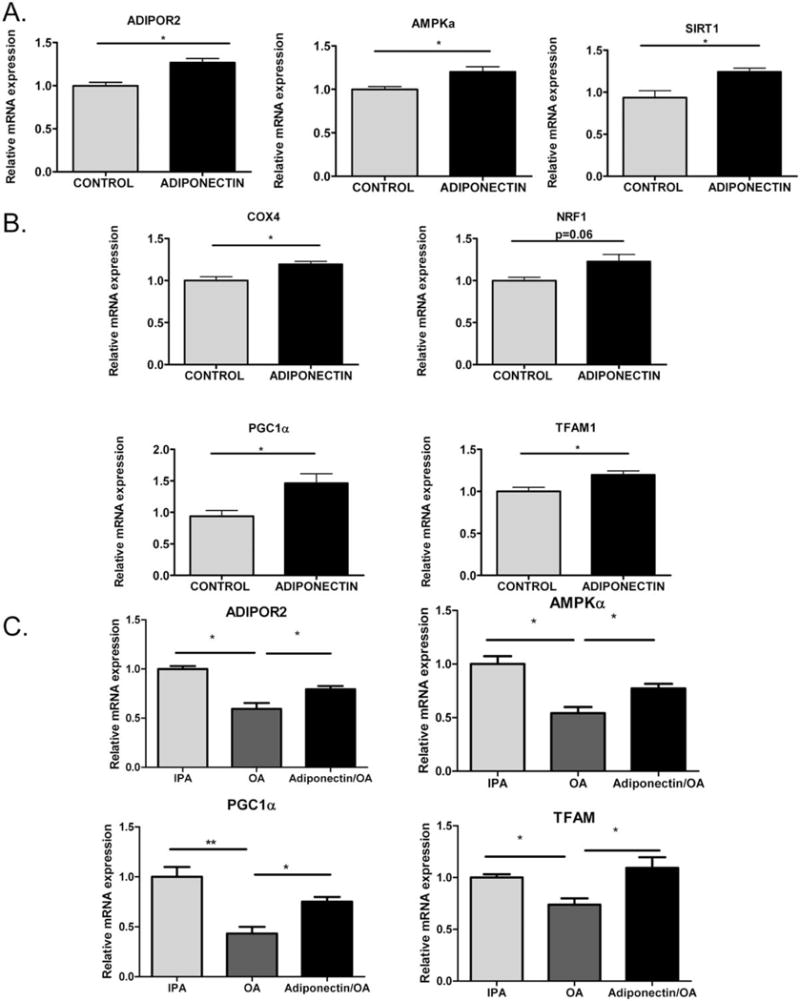

Adiponectin Promotes Gene Expression Related to Adiponectin Signaling and Mitochondrial Gene Expression in Hepatocytes In Vitro

AML-12 cells were treated with recombinant full-length adiponectin (20 μg/mL) to examine the specific and individual effect of adiponectin. Adiponectin-treated hepatocytes showed an increase in expression levels of genes related to adiponectin signaling, such as Adipor2, Ampkα, and Sirt1 (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, levels of mitochondrial biogenesis and β-oxidation related genes including Cox4, Pgc1α, and Tfam were also significantly elevated by adiponectin treatment relative to untreated controls (Fig. 6B). Adiponectin treatment also led to an increase in Nrf1 expression levels, but the increase was not statistically significant (P = 0.06).

Fig. 6.

Adiponectin promotes gene expression of mitochondrial biogenesis pathway in hepatocytes. (A) Relative mRNA expression of Adipor2, Ampkα, and Sirt1 was determined from AML-12 hepatocytes treated with recombinant full-length adiponectin (20 μg/mL) for 24 hours in 1% FBS containing AML-12 media relative to untreated controls. n = 3. (B) Relative mRNA expression levels of Cox4, Nrf1, Pgc1α, and Tfam were determined from AML-12 hepatocytes treated with recombinant full-length adiponectin (20 μg/mL) for 24 hours in 1% FBS containing AML-12 media relative to untreated controls. n = 3. The experiment was repeated three times and representative data are shown. (C) Adiponectin restores impaired adiponectin signaling and mitochondrial biogenesis-related gene expression levels in lipid-loaded AML-12 hepatocytes: AML-12 cells were treated with 250 μM OA for 24 hours with or without adiponectin (20 μg/mL) in 1% FBS containing AML-12 growth media. Control cells were treated with isopropanol (IPA, final concentration 0.5%). Relative mRNA expression levels of Adipor2, Ampkα, Pgc1α, and Tfam was determined. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 indicates statistical significance.

We also examined whether the effect of adiponectin on adiponectin signaling and mitochondrial gene expression was observed in the setting of free-fatty acid exposure in AML-12 hepatocytes. Cells were treated with 250 μM oleic acid (OA) for 24 hours with or without adiponectin in the presence of 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS) containing AML12 media. After 24 hours of treatment with OA, there was a significant reduction in the gene expression levels of Adipor2, Ampkα, Pgc1α, and Tfam relative to isopropanol-treated controls. Notably, adiponectin treatment was able to appreciably up-regulate the gene expression levels in the “steatotic” AML-12 cells also, partially mitigating the repression exerted by the free-fatty acid exposure (Fig. 6C).

We have also extended these studies to primary rat hepatocytes, and find that, as compared to OA-treated hepatocytes, those treated with recombinant adiponectin and OA showed significantly elevated levels of AMPKα, SIRT1, PGC1α, and TFAM (Supporting Fig. 2).

Discussion

We have shown that obese, diabetic mice fed a diet high in unsaturated fat are prone to rapid development of severe obesity, NAFLD and NASH. The single most important determinant of NASH development in this model appears to be adiponectin depletion, which develops after a critical level of weight gain. Significantly, the development of the NASH phenotype is rapid and was observed as early as 5 weeks, Leprdb/db HF mice developed steatohepatitis with inflammatory foci, consistent ballooning, increased apoptosis, and a metabolic phenotype resembling human NASH. No previous models to our knowledge have shown serum adiponectin as an independent predictor of NASH developing in concert with a threshold level of increase in body mass. Importantly, we also demonstrated that 10 weeks of ad libitum feeding of this diet to C57BL/6 mice does not lead to weight gain, liver damage, or artificially lowered adiponectin levels. However, one limitation of our experimental model is the severe leptin resistance present in this mouse model, which may limit the extrapolation of our findings to human NASH, wherein hepatic leptin resistance is also a feature, albeit to a lesser degree than this model.

Clinical observations have shown that obesity can lead to decreased serum adiponectin levels,37 lower Adipoq expression in various fat depots,38 and reduced hepatic levels of adiponectin receptor-2,39 supporting our hypothesis for a central role for adiponectin depletion in the metabolic sequelae of obesity.

Previous studies have attempted to recapitulate human NASH using murine models of dietary and genetic models. However, several of these studies used diets containing saturated fats and additional factors (i.e., fructose or cholesterol), often over a period of 5–6 months.6,9,19,28 While these complex models may emulate the common dietary combinations seen in a Western diet and reproduce the histologic features of NASH, they have limitations in interpreting their effect on NASH-induction pathways because their obesity-independent effects on inflammation, apoptosis, or ER stress may confound the influence of weight gain on the NASH phenotype.

A novel aspect of our model was the ability to produce NASH within 5 weeks using the same criteria as used for human studies.32 Prior models using unsaturated fat feeding and genetically based hyperphagia were shown to develop hepatic fibrosis over a longer period of time,12,20,21 suggesting that the model used in the current study may also recreate fibrosis associated with NASH over time.

In this study we demonstrated that the most important cause of NASH in obesity-related weight gain in a genetic model of obesity and diabetes is adiponectin depletion. While hypoadiponectinemia is an important feature of the metabolic syndrome, adiponectin depletion has not been reported in many earlier models of obesity and NAFLD/NASH.8,10,11,13–16,18,20,21 Our model showed a significant decrease of 5–6 μg/mL in plasma adiponectin at both the 5- and 10-week time-points, which was clearly linked to advanced obesity. Not only was serum adiponectin distinctly lower in Leprdb/db HF mice at both timepoints, it was an independent predictor of both NAFL and NASH. Previous studies using adiponectin knockout mice, and the use of adiponectin supplementation-related studies have provided useful lessons for the potential pathways of adiponectin action in protection against NASH progression. These mice are prone to development of hepatic steatosis, mitochondrial dysfunction, M1 macrophage activation, diminished M2 antiinflammatory markers, and steatohepatitis.40–43 Mechanistic studies through knockout models and 3T3-L1 adipocytes revealed that the main therapeutic action of adiponectin is through the activation of the AMP-active protein kinase (AMPK) pathway.33,44

It should be pointed out that, while ω-3 fats have been associated with beneficial outcomes and ω-6 fats have been associated with worsening fatty liver disease in several animal studies,29,30 NASH in human subjects has not been shown to develop from overfeeding polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), which is a caveat to the extrapolation of our findings to human NASH. Also, while it is known that there is a greater depletion of ω-3 fats compared to ω-6 fats in human NASH patients,30,45 there is no clear evidence that consuming ω-6 PUFAs in amounts greater than ω-3 fats will lead to NASH in humans. Further, while some studies show that ω-3 PUFAs may improve hepatic steatosis in humans,45 more detailed studies need to be done to determine the duration and dose to assess improvement of NASH.45

In our model, weight gain due to unsaturated HF-feeding of Leprdb/db mice led to visceral adipose tissue inflammation characterized by hypoxia, macrophage infiltration, and M1 activation, which could have contributed to the depletion of adiponectin.46 Since adiponectin is known to exert multiple hepatoprotective effects such as regulating lipid metabolism, mitigating inflammation, and preventing cell death,47 among others, its impaired production and signaling could have led to the major histological features of NASH observed in our mouse model: steatosis, inflammation, ballooning and apoptosis.

Adiponectin regulates hepatic energy homeostasis function through its receptors, adiponectin receptor-1(AdipoR1) and receptor-2 (AdipoR2), which signal through AMPK, to govern fatty acid oxidation, triglyceride synthesis, and mitochondrial biogenesis.33,48 Mitochondrial function is further regulated by the transcription factors PGC1α, NRF1, and the mitochondrial transcription factor, TFAM. SIRT1, an NAD+ dependent deacytelase is also an important nutrient sensor and regulator of liver energy homeostasis and mitochondrial function, using PGC1α as one of its targets for deacetylation, thereby activating it.34 In addition, AMPK regulates mitochondrial biogenesis not only through increased production, but also activation of PGC1α.35

In our NASH model, a critical threshold of weight gain led to hypoadiponectinemia and concomitant reduction of its liver-specific receptor, AdipoR2-exacerbating a feedforward “adiponectin resistance” in the liver leading to inactivation of the downstream effectors of its various target pathways: lipid metabolism and mitochondrial biogenesis. Strikingly, we show that protein levels of AdipoR2, LKB1, activated AMPKα, and mitochondrial regulators including PGC1α were reduced in the livers of NASH mice compared to NAFL mice, implying that adiponectin depletion-mediated impairment of mitochondrial biogenesis is a major factor in the transition from simple steatosis to NASH. Significantly, we also demonstrate that the direct addition of recombinant full-length adiponectin to the AML-12 hepatocytes in vitro stimulated genes associated with mitochondrial biogenesis. It is noteworthy that we used a form of adiponectin, which has previously been demonstrated to form high molecular weight (HMW) oligomers. HMW oligomers of adiponectin has been shown to be the bioactive form of adiponectin capable of exerting its multiple beneficial effects on the liver.47 Furthermore, we showed that while lipid-loading of AML-12 hepatocytes led to a decrease in the gene expression levels of Ampkα, Adipor2, Pgc1α, and Tfam, addition of adiponectin appreciably ameliorated the down-regulation exerted by lipid loading. Data from clinical studies also imply that mitochondrial dysfunction, indicated by mitochondrial structural defects, distinguishes NAFLD from NASH.49 In support of our findings regarding the critical role of adiponectin-AMPK signaling in mitochondrial biogenesis, Galic et al.50 recently showed hematopoietic AMPK deficiency causes reduced mitochondrial function and increased inflammation. Thus, our study links adiponectin depletion to hepatic mitochondrial dysfunction in an in vivo model.

These data provide support to the hypothesis that weight gain from an HF diet past a “tipping point” results in decreased adiponectin production from the adipose tissue, which then drives NASH by impaired mitochondrial β-oxidation of an increased fatty acid load in the setting of fatty liver.

In conclusion, we have successfully developed a small-animal model that accurately recapitulates the histological features of human NASH associated with obesity and diabetes. The rapid progression to NASH with consistent hepatocellular ballooning as early as 5 weeks makes our model attractive for interventional studies. Our model also provides insights into the development of NASH by obesity-induced adiponectin depletion and consequent dysregulation of hepatic lipid metabolism and mitochondrial biogenesis and highlights the direct effect of adiponectin in regulating hepatic mitochondrial biogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by Liver Center of Excellence Research Fund, Virginia Mason Medical Center to K.V.K.

Abbreviations

- AdipoR2

Adiponectin receptor-2

- AMPK

adenosine monophosphate activated protein kinase

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- PGC1α

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha

- SIRT1

sirtuin 1 (silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog 1)

Footnotes

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

References

- 1.Schattenberg JM, Schuppan D. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: the therapeutic challenge of a global epidemic. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2011;22:479–488. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32834c7cfc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brunt EM. Pathology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:195–203. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrne CD. Ectopic fat, insulin resistance and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Proc Nutr Soc. 2013;14:1–8. doi: 10.1017/S0029665113001249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahn SE, Hull RL, Utzschneider KM. Mechanisms linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2006;444:840–846. doi: 10.1038/nature05482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gatselis NK, Ntaios G, Makaritsis K, Dalekos GN. Adiponectin: a key playmaker adipocytokine in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Exp Med. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10238-012-0227-0. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charlton M, Krishnan A, Viker K, Sanderson S, Cazanave S, McConico A, et al. Fast food diet mouse: novel small animal model of NASH with ballooning, progressive fibrosis, and high physiological fidelity to the human condition. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;301:G825–G834. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00145.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Townsend KL, Lorenzi MM, Widmaier EP. High-fat diet-induced changes in body mass and hypothalamic gene expression in wild-type and leptin-deficient mice. Endocrine. 2008;33:176–188. doi: 10.1007/s12020-008-9070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsuzawa N, Takamura T, Kurita S, Misu H, Ota T, Ando H, et al. Lipid-induced oxidative stress causes steatohepatitis in mice fed an atherogenic diet. HEPATOLOGY. 2007;46:1392–1403. doi: 10.1002/hep.21874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ito M, Suzuki J, Tsujioka S, Sasaki M, Gomori A, Shirakura T, et al. Longitudinal analysis of murine steatohepatitis model induced by chronic exposure to high-fat diet. Hepatol Res. 2007;37:50–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romestaing C, Piquet MA, Bedu E, Rouleau V, Dautresme M, Hourmand-Ollivier I, et al. Long term highly saturated fat diet does not induce NASH in Wistar rats. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2007;4:4. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-4-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaemers IC, Stallen JM, Kunne C, Wallner C, van Werven J, Nederveen A, et al. Lipotoxicity and steatohepatitis in an overfed mouse model for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1812:447–458. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baumgardner JN, Shankar K, Hennings L, Badger TM, Ronis MJ. A new model for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in the rat utilizing total enteral nutrition to overfeed a high-polyunsaturated fat diet. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G27–G38. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00296.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed U, Redgrave TG, Oates PS. Effect of dietary fat to produce non-alcoholic fatty liver in the rat. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1463–1471. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zou Y, Li J, Lu C, Wang J, Ge J, Huang Y, et al. High-fat emulsion-induced rat model of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Life Sci. 2006;79:1100–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akin H, Deniz M, Tahan V, Can G, Kedrah AE, Celikel C, et al. High-fat liquid “Lieber-DeCarli” diet for an animal model of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: does it really work? Hepatol Int. 2007;1:449–450. doi: 10.1007/s12072-007-9028-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lieber CS, Leo MA, Mak KM, Xu Y, Cao Q, Ren C, et al. Model of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:502–509. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.3.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y, Ausman LM, Russell RM, Greenberg AS, Wang XD. Increased apoptosis in high-fat diet-induced nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in rats is associated with c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activation and elevated proapoptotic Bax. J Nutr. 2008;138:1866–1871. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.10.1866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deng QG, She H, Cheng JH, French SW, Koop DR, Xiong S. Steato-hepatitis induced by intragastric overfeeding in mice. HEPATOLOGY. 2005;42:905–914. doi: 10.1002/hep.20877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larter CZ, Yeh MM, Van Rooyen DM, Teoh NC, Brooling J, Hou JY, et al. Roles of adipose restriction and metabolic factors in progression of steatosis to steatohepatitis in obese, diabetic mice. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1658–1668. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carmiel-Haggai M, Cederbaum AI, Nieto N. A high-fat diet leads to the progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in obese rats. FASEB J. 2005;19:136–138. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2291fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trak-Smayra V, Paradis V, Massart J, Nasser S, Jebara V, Fromenty B. Pathology of the liver in obese and diabetic ob/ob and db/db mice fed a standard or high-calorie diet. Int J Exp Pathol. 2011;92:413–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2011.00793.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joshi-Barve S, Barve SS, Amancherla K, Gobejishvili L, Hill D, Cave M, et al. Palmitic acid induces production of proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-8 from hepatocytes. HEPATOLOGY. 2007;46:823–830. doi: 10.1002/hep.21752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang D, Wei Y, Pagliassotti MJ. Saturated fatty acids promote endoplasmic reticulum stress and liver injury in rats with hepatic steatosis. Endocrinology. 2006;147:943–951. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopez S, Bermudez B, Abia R, Muriana FJ. The influence of major dietary fatty acids on insulin secretion and action. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2010;21:15–20. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3283346d39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mei S, Ni HM, Manley S, Bockus A, Kassel KM, Luyendyk JP, et al. Differential roles of unsaturated and saturated Fatty acids on autophagy and apoptosis in hepatocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;339:487–498. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.184341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nomura K, Yamanouchi T. The role of fructose-enriched diets in mechanisms of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Nutr Biochem. 2012;23:203–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Rooyen DM, Larter CZ, Haigh WG, Yeh MM, Ioannou G, Kuver R, et al. Hepatic free cholesterol accumulates in obese, diabetic mice and causes nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1393–1403. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Savard C, Tartaglione EV, Kuver R, Haigh WG, Farrell GC, Subramanian S, et al. Synergistic interaction of dietary cholesterol and dietary fat in inducing experimental steatohepatitis. HEPATOLOGY. 2013;57:81–92. doi: 10.1002/hep.25789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aguilera CM, Ramirez-Tortosa CL, Quiles JL, Yago MD, Martinez-Burgos MA, Martinez-Victoria E, et al. Monounsaturated and omega-3 but not omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids improve hepatic fibrosis in hypercholesterolemic rabbits. Nutrition. 2005;21:363–371. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2004.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El-Badry AM, Graf R, Clavien PA. Omega 3 – Omega 6: what is right for the liver? J Hepatol. 2007;47:718–725. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang L, Wang Q, Yu Y, Zhao F, Huang P, Zeng R, et al. Leptin contributes to the adaptive responses of mice to high-fat diet intake through suppressing the lipogenic pathway. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6884. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van NM, Behling C, Contos MJ, Cummings OW, et al. Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. HEPATOLOGY. 2005;41:1313–1321. doi: 10.1002/hep.20701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buechler C, Wanninger J, Neumeier M. Adiponectin, a key adipokine in obesity related liver diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:2801–2811. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i23.2801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silva JP, Wahlestedt C. Role of Sirtuin 1 in metabolic regulation. Drug Discov Today. 2010;15:781–791. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Civitarese AE, Smith SR, Ravussin E. Diet, energy metabolism and mitochondrial biogenesis. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2007;10:679–687. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3282f0ecd2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spiegelman BM. Transcriptional control of mitochondrial energy metabolism through the PGC1 coactivators. Novartis Found Symp. 2007;287:60–63. discussion 63-69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Polyzos SA, Toulis KA, Goulis DG, Zavos C, Kountouras J. Serum total adiponectin in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Metabolism. 2011;60:313–326. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu E, Liang P, Spiegelman BM. AdipoQ is a novel adipose-specific gene dysregulated in obesity. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10697–10703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tomita K, Oike Y, Teratani T, Taguchi T, Noguchi M, Suzuki T, et al. Hepatic AdipoR2 signaling plays a protective role against progression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. HEPATOLOGY. 2008;48:458–473. doi: 10.1002/hep.22365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou M, Xu A, Tam PK, Lam KS, Chan L, Hoo RL, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to the increased vulnerabilities of adiponectin knockout mice to liver injury. HEPATOLOGY. 2008;48:1087–1096. doi: 10.1002/hep.22444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Asano T, Watanabe K, Kubota N, Gunji T, Omata M, Kadowaki T, et al. Adiponectin knockout mice on high fat diet develop fibrosing steatohepatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1669–1676. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fukushima J, Kamada Y, Matsumoto H, Yoshida Y, Ezaki H, Takemura T, et al. Adiponectin prevents progression of steatohepatitis in mice by regulating oxidative stress and Kupffer cell phenotype polarization. Hepatol Res. 2009;39:724–738. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2009.00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mandal P, Pratt BT, Barnes M, McMullen MR, Nagy LE. Molecular mechanism for adiponectin-dependent M2 macrophage polarization: link between the metabolic and innate immune activity of full-length adiponectin. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:13460–13469. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.204644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Y, Zhou M, Lam KS, Xu A. Protective roles of adiponectin in obesity-related fatty liver diseases: mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2009;53:201–212. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302009000200012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scorletti E, Byrne CD. Omega-3 fatty acids, hepatic lipid metabolism, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Annu Rev Nutr. 2013;33:231–248. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071812-161230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ye J, Gao Z, Yin J, He Q. Hypoxia is a potential risk factor for chronic inflammation and adiponectin reduction in adipose tissue of ob/ob and dietary obese mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E1118–1128. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00435.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Finelli C, Tarantino G. What is the role of adiponectin in obesity related non-alcoholic fatty liver disease? World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:802–812. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i6.802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Iwabu M, Yamauchi T, Okada-Iwabu M, Sato K, Nakagawa T, Funata M, et al. Adiponectin and AdipoR1 regulate PGC-1alpha and mitochondria by Ca(2+) and AMPK/SIRT1. Nature. 2010;464:1313–1319. doi: 10.1038/nature08991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sanyal AJ, Campbell-Sargent C, Mirshahi F, Rizzo WB, Contos MJ, Sterling RK, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: association of insulin resistance and mitochondrial abnormalities. Gastroenterology. 2001;20:1183–1192. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.23256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Galic S, Fullerton MD, Schertzer JD, Sikkema S, Marcinko K, Walkley CR, et al. Hematopoietic AMPK b1 reduces mouse adipose tissue macrophage inflammation and insulin resistance in obesity. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4903–4915. doi: 10.1172/JCI58577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.