Abstract

Objective

To introduce and validate a novel flow-independent dark-blood delayed-enhancement MRI technique (FIDDLE) that depicts hyperenhanced myocardium while simultaneously suppressing blood-pool signal.

Background

The diagnosis and assessment of myocardial infarction (MI) is crucial in determining clinical management and prognosis. Although delayed-enhancement-MRI (DE-MRI) is an in-vivo reference standard for imaging MI, an important limitation is poor delineation between hyperenhanced myocardium and bright LV cavity blood-pool, which may cause many infarcts to become invisible.

Methods

A canine model with pathology as the reference standard was used for validation (n=22). Patients with MI and normal controls were studied to ascertain clinical performance (n=31).

Results

In canines, FIDDLE was superior to conventional DE-MRI for the detection of MI with higher sensitivity (96% vs 85%, p=0.002) and accuracy (95% vs 87%, p=0.01) with similar specificity (92% vs 92%, p=1.0). In infarcts that were identified by both techniques, the entire length of the endocardial border between infarcted myocardium and adjacent blood-pool was visualized in 33% for DE-MRI compared with 100% for FIDDLE. There was better agreement for FIDDLE-measured infarct size than for DE-MRI infarct size (95% limits-of-agreement, 2.1% versus 5.5%, p<0.0001). In patients, findings were similar; FIDDLE demonstrated higher accuracy for the diagnosis of MI (100% [95% CI: 89–100%] versus 84% [66–95%], p=0.03).

Conclusions

We introduce and validate a novel MRI technique that improves the discrimination of the border between infarcted myocardium and adjacent blood-pool. This dark-blood technique provides superior diagnostic performance than the current in-vivo reference standard for the imaging diagnosis of MI.

Keywords: myocardial infarction, diagnosis, infarct size, magnetic resonance imaging

INTRODUCTION

Myocardial infarction (MI) is the leading cause of congestive heart failure and death in the industrialized world. Detection of MI is essential, since even small infarcts are associated with worse prognosis,1 and there are proven therapies that can improve outcome. Even when the diagnosis of MI is known, assessment of the size, location, and transmural-extent of infarction is important for patient management decisions, such as whether to undergo coronary revascularization, resynchronization therapy, or cardioverter-defibrillator implantation.2

Delayed-enhancement MRI (DE-MRI) is considered to be the in-vivo reference standard for imaging MI, given its ability to generate high resolution spatial maps of infarcted and viable myocardium. Accordingly, it is increasingly being used in clinical practice and in randomized trials evaluating novel MI treatments to provide a measure of therapeutic efficacy.2

One important limitation of DE-MRI, however, is that infarcted myocardium and the LV blood-pool often hyperenhance to a similar degree following contrast media administration.3 Hence, infarcted myocardium may be hidden when immediately adjacent to the LV cavity since there is poor delineation between bright tissue and bright blood-pool. This may explain why a recent multicenter trial evaluating the performance of DE-MRI demonstrated that up to 21% of infarcts may be missed in select patient cohorts (i.e. those with non-Q-wave chronic MI).4

Traditional “black-blood” MRI techniques provide improved delineation of tissue by suppressing signal from adjacent blood-pool.5 However, these techniques depend upon the long T1 of blood (~2secs at 3T) and sufficient blood flow within this time period to generate black-blood images. Hence, traditional techniques are not designed to work after contrast administration (which greatly shortens blood T1) and cannot be used to provide contrast-enhanced, black-blood images of tissues.

In this study, we introduce a novel Flow-Independent Dark-blood DeLayed Enhancement technique (FIDDLE) that allows visualization of tissue contrast-enhancement while simultaneously suppressing blood-pool signal. We validate FIDDLE in an animal model of MI and demonstrate its clinical performance in patients.

METHODS

FIDDLE

The pulse sequence timing diagram and evolution of longitudinal magnetization for different tissue components are shown in Fig 1.6,7 The primary components are: (1) a preparatory module that affects the magnetization of myocardium differently than blood, (2) an inversion-recovery pulse (IR), (3) phase-sensitive reconstruction, and (4) an inversion time (TI) selected such that blood magnetization is less than tissue.

Figure 1. FIDDLE timing diagram.

Primary components are: (1) preparatory module, (2) inversion recovery pulse, (3) phase-sensitive reconstruction, and (4) inversion time such that blood magnetization is less than tissue magnetization (“Black-blood Condition”). Even with inversion times outside the black-blood condition, blood-pool signal is suppressed compared with DE-MRI, which improves the conspicuity of infarcted myocardium.

M0=baseline longitudinal magnetization; Mz=blood or tissue magnetization.

Because the magnetization of blood is made more negative than normal myocardium (i.e. blood Mz < myocardial Mz, “Black-Blood Condition”), phase-sensitive reconstruction renders blood in the cardiac chambers darker than myocardium by remapping the magnetization to positive-only values. As a result, a precise TI is not needed to make the blood black—rather, a range of TIs can be used, so long as the magnetization of blood is more negative than that of myocardium (Fig 1).

Pilot Study

Theoretically, any pulse that affects the magnetization of myocardium differently than blood can be used as the initial preparatory module.8 We chose a magnetization-transfer (MT) module, and performed a pilot study prior to the main investigation in a canine model. The pilot study involved two parts: first, empiric data were acquired in-vivo to characterize the effects of the MT-prep module on the magnetization of normal myocardium, infarcted myocardium, and blood-pool; and second, the data from these in-vivo experiments were used to simulate the effects of TI on the signal intensity of these tissues.

For the pilot in-vivo experiments, the animal preparation was the same as for the main study (details below) but performed in a separate cohort of canines. Imaging was performed 15 minutes after intravenous gadoversetamide (0.15mmol/kg) administration using an MT-prep module (a train of gaussian radiofrequency pulses each 5.12ms in duration) that was immediately followed by a single-shot steady-state free-precession (SSFP) readout. The effects of MT-prep train length (1–20 repetitions in steps of 1), flip angle (200°–900° in steps of 50°), and off-resonance frequency (200–1500Hz in steps of 100Hz) on tissue magnetization were measured.

Simulations were then performed in MATLAB (MathWorks). The effects of readout pulses, diffusion, and imperfections in the inversion pulse were assumed to be negligible. The longitudinal magnetization following the MT-prep and IR-pulse for a given tissue species (a) as a function of time (t) was expressed as:

| (1) |

where M0,a is the equilibrium magnetization of each tissue species, MTeff is the signal immediately after the MT-prep (based on the canine data), and T1,a is the T1 of the species. T1 values of 410ms, 630ms, and 440ms for infarct, normal myocardium (myo), and blood, respectively, were used assuming typical conditions for delayed-enhancement imaging at 3T.9 Following phase-sensitive reconstruction, and assuming the black-blood condition (Mblood(t) ≤ minimum {Mmyo(t), Minfarct(t)}), the signal of normal myocardial tissue (or infarcted tissue) normalized to equilibrium magnetization was calculated as:

| (2) |

Canine Protocol Overview and Pathology

Following optimization of the MT-prep module in the pilot study, the diagnostic performance of FIDDLE was assessed with pathology as the reference standard. For both the pilot and main investigation, the same canine model of MI was used. MI was produced by occluding the left anterior descending coronary artery or the left circumflex artery (obtuse marginal branch) under sterile conditions after a thoracotomy. To investigate a wide range of infarct sizes and transmurality, we employed a range of occlusion times (40—90 minutes) followed by reperfusion.10 As a point-of-reference, a 40-minute occlusion in the canine model leads to a subendocardial infarct that averages 38% transmural.11 The care and treatment of canines followed the Position of the American Heart Association on Research Animal Use.12 The protocol was approved by the Duke University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Following MRI, the heart was removed, and the infarcted region was confirmed using histochemical staining.13

MRI

MRI was performed at a range of time-points following MI to test if infarct age might affect the performance of FIDDLE. The range was 2 days to 7 months with 14 scanned within the first 2 weeks, and 8 after two weeks (median 14 weeks). Images were acquired on a 3T Siemens Verio during ventilated breathholds. DE-MRI and FIDDLE were performed immediately after one another in random order using matched parameters (e.g. slice thickness, 7mm; in-plane spatial resolution, 1.2×1.0mm; temporal resolution, 180ms; TR, 2 R-R intervals; breathhold time, 8–10s) 15 minutes after intravenous gadoversetamide (0.15mmol/kg) administration.

A segmented, inversion-recovery gradient-echo sequence was used for DE-MRI, with TI manually selected to null signal from normal myocardium.4 FIDDLE consisted of an MT-prep module and IR-pulse followed by a segmented SSFP readout (TE, 1.36ms; flip angle, 50°; bandwidth 975Hz/pixel; averages, 2). The parameters for the MT-prep module were selected based on the findings from the pilot study (train length, 19; flip angle, 500°; offset frequency, 800Hz). The TI was manually selected to render blood black and maximize image contrast between infarcted and normal myocardium. This was performed by selecting the longest TI (typically 200–280ms) that still resulted in black-blood. A complete short-axis stack of DE-MRI and FIDDLE images were obtained.

Image Analysis

Pathology slices were registered with MR images using myocardial landmarks. Pathology, FIDDLE, and DE-MRI studies were read separately, blinded to other data. Window and level for MRI images were preset so that noise was still detectable and infarcted regions were not over-saturated.14 The presence of MI was determined by visual inspection. Image were also examined to determine if the entire length of the infarct subendocardial border could be discriminated from the adjacent blood-pool. Infarct size (%LV mass) was measured by planimetry of the stack of short-axis pathology and MR images. The transmural-extent of infarction was expressed as percent myocardial sector area on a slice-by-slice basis.10 Measurements were performed at our core laboratory which undergoes regular audits and testing for quality assurance (e.g. inter- and intraobserver agreement of infarct size demonstrates a bias of 1.0% and −0.1%, respectively with a standard deviation of differences of 2.6% and 0.8%, respectively).

Patients

Patients presenting with history of MI were recruited prospectively. The diagnosis of MI was based on the Universal Definition. Patients <18 years old or with history of multiple infarcts were excluded. Consecutive patients who underwent coronary angiography during admission for MI with clear culprit infarct-related-artery, and who agreed to participate were enrolled. The control group consisted of subjects without known coronary disease and with low probability for developing disease over the next 10 years (lowest Framingham risk score: 1% for women, 2% for men).15 All participants gave written informed consent, which was approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board.

The MRI protocol was the same as in canines, and the same sequences were used with similar settings. However, to test the generalizability of FIDDLE, half of the patients were scanned at 3T and half at 1.5T. FIDDLE and DE-MRI were performed using matched parameters (3T: slice thickness, 6mm; in-plane spatial resolution, 1.7×1.3mm; temporal resolution, 180ms; TR, 2 R-R intervals. 1.5T: slice thickness, 8mm; in-plane spatial resolution, 1.9×1.4mm; temporal resolution, 180ms; TR, 2 R-R intervals). FIDDLE incorporated 2 averages, however, the breathhold time was the same as for DE-MRI (~8–10sec) since FIDDLE utilized an SSFP readout with twice the k-space lines per segment (59 vs 29). The MT-prep parameters were similar at 3T (train length, 19; flip angle, 500°; offset frequency, 800Hz) and 1.5T (train length, 19; flip angle, 500°; offset frequency, 600Hz).

Images were obtained 15 minutes after intravenous gadoversetamide (0.15mmol/kg) administration in multiple short-axis (every 10mm throughout the LV) and 3 long-axis views. MRI analysis was the same as for canines, and FIDDLE and DE-MRI were interpreted independently, masked to patient identity and clinical information. Additionally, MR images were scored on a 17-segment model to determine the infarct location. Coronary angiograms, in patients with MI, were read blinded to all other information and analyzed in order to localize the perfusion territory of the infarct-related-artery on a 17-segment model.4 MR localization of infarction was categorized as correct or incorrect based upon the match with the infarct-related-artery perfusion territory on coronary angiography, as previously described.4

Specific Absorption Rate (SAR)

All scans were performed under strict adherence to FDA guidelines for SAR (<4 W/kg averaged over the whole body for any 15-minute period). The vendor calculated whole body SAR was collected from the DICOM header.

Contrast-to-Noise Ratio (CNR)

A separate group of patients—all with a clearly identifiable infarct on conventional DE-MRI— were recruited in order to measure infarct-to-normal myocardium CNR. Both FIDDLE and DE-MRI images were obtained and then reconstructed directly in SNR units.16 CNR was calculated by subtracting the SNR from manually drawn regions-of-interest on the SNR scaled image reconstructions.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous data are presented as mean±SD or as median and interquartile range as appropriate. McNemar’s test was used to compare the diagnostic performance of methods. Linear regression analysis was used to compare the relationships between infarct size by MRI and pathology, accounting for measurements from the same subject. Bland–Altman analysis was performed to assess the agreement between MRI and pathology measurements but modified to use the pathology measurements as the reference. Statistical tests were 2-tailed; P<0.05 was considered significant. SAS (Cary, NC) was used to perform the analyses.

RESULTS

Pilot Study

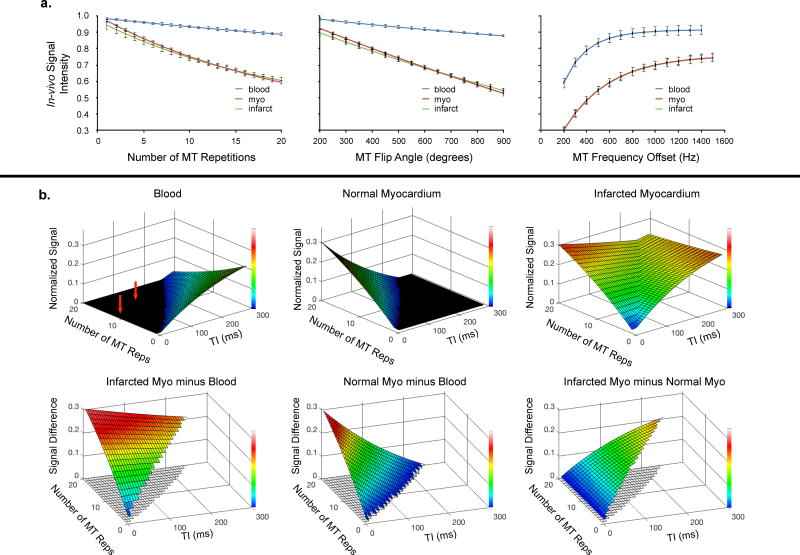

The effects of the MT-prep parameters on in-vivo tissue signal were measured in 8-canines with 1-week old MI. Increasing train length, increasing flip angle, and decreasing off-resonance frequency reduced signal intensity for all tissues (Fig 2a). However, the effect was substantially increased for myocardium compared with blood. Differences were negligible between normal and infarcted myocardium.

Figure 2. Pilot study.

a. In-vivo characterization of MT-prep module in canines. Increasing train length, holding flip angle and frequency offset constant (600° and 800Hz), reduced signal particularly for normal (myo) and infarcted myocardium (left panel). Increasing flip angle, holding train length and frequency offset constant (14 and 800Hz), reduced signal, again especially for myocardial tissue (middle panel). Increasing frequency offset, holding train length and flip angle constant (14 and 600°), led to increased signal for myocardium and blood (right panel).

b. Modeled FIDDLE signal behavior. Top row: Signal of blood, normal myocardium, and infarcted myocardium as a function of MT-prep train length and inversion time (TI). Bottom row: Differences in signals when blood-pool signal is nulled.

These data were then used to model the signal behavior of FIDDLE (Fig 2b). These simulations show: (1) blood-pool signal is nulled (i.e. black-blood condition is met) over a wide range of MT-prep train lengths and inversion times (red arrows); (2) Infarct signal is high over a wide range, leading to a large difference in signal between infarcted myocardium and blood, and (3) when blood-pool signal is nulled, longer inversion times lead to increased signal differences between normal and infarcted myocardium.

Canines

The performance of FIDDLE was assessed in 22 canines. Data from all canines surviving surgery were included. Examples of in-vivo MRI are shown in Fig 3a. In subjects 1–3, hyperenhanced regions are visible on DE-MRI and appear to match the infarcted regions by pathology (blue arrows). In subjects 4–5, the exact border between hyperenhanced myocardium on DE-MRI and the bright LV cavity blood-pool is not always clear. In contradistinction, for all 5 subjects, hyperenhanced regions are clearly visible on FIDDLE and the complete borders are easily distinguished from adjacent blood-pool and normal myocardium. Moreover, the shape and contour of hyperenhancement on FIDDLE closely resembles the infarcted regions by pathology.

Figure 3. Examples of DE-MRI and FIDDLE compared with pathology.

Matched DE-MRI and FIDDLE images in 5 subjects (a) and multiple short-axis images in 1 subject (b). See text for details.

Fig 3b shows comparisons in one subject at multiple short-axis locations. Pathology demonstrates a small subendocardial infarct involving the inferoseptum and the posteromedial papillary muscle, spanning from the base to the apex. The infarct is clearly depicted by FIDDLE, but it is poorly visualized by DE-MRI on many short-axis locations.

Table 1 summarizes the diagnostic performance of FIDDLE and DE-MRI for the diagnosis of MI compared to pathology (n=136 slices). Overall, sensitivity and accuracy for FIDDLE (96% and 95%, respectively) were higher than that for DE-MRI (85% and 87%, respectively). Specificity was similarly high for both). When only pathology slices with ≤25% transmural infarction were considered (n=87), sensitivity and accuracy remained high for FIDDLE and were again significantly higher than that for DE-MRI (sensitivity: 98% vs 80%; accuracy: 95% vs 85%; p≤0.02 for both). Specificity remained 92% for both.

Table 1.

Diagnostic Performance of FIDDLE

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canines | |||

| DE-MRI | 83/98, 85% (76–91%) | 35/38, 92% (79–98%) | 118/136, 87% (80–92%) |

|

| |||

| FIDDLE | 94/98, 96% (90–99%) | 35/38, 92% (79–98%) | 129/136, 95% (90–98%) |

|

| |||

| p-value | 0.002 | 1.0 | 0.01 |

|

| |||

| Patients | |||

| DE-MRI | 17/20, 85% (62–97%) | 9/11, 82% (48–98%) | 26/31, 84% (66–95%) |

|

| |||

| FIDDLE | 20/20, 100% (83–100%) | 11/11, 100% (72–100%) | 31/31, 100% (89–100%) |

|

| |||

| p-value | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.03 |

Values in parenthesis represents 95% confidence intervals

There was no relationship between infarct age and the diagnostic performance of FIDDLE. Accuracy was 93% for ≤2-week-old MI and 97% for >2-week-old MI (p=0.35). In infarcts that were identified by both techniques, the entire length of the endocardial border between infarcted myocardium and adjacent blood-pool was visualized in 100% for FIDDLE compared with 33% for DE-MRI. There was no evidence of “slow blood flow” artifacts in the LV cavity in any of the FIDDLE images.

On a per subject basis, infarct size by FIDDLE (r=0.99) and DE-MRI (r=0.98) were highly correlated with infarct size by pathology (Fig 4a). Bland-Altman analyses demonstrated that the level of agreement was high for both comparisons with pathology (Fig 4b). However, DE-MRI showed a small, but significant bias (−1.1%, p=0.001), whereas, FIDDLE showed no bias (−0.01%, p=0.38). Additionally, 95% limits-of-agreement were larger for DE-MRI (−3.9%, 1.6%) compared with FIDDLE (−1.1%, 0.9%).

Figure 4. Comparison of infarct size by FIDDLE and DE-MRI to pathology.

Linear regression (a) and Bland-Altman plots (b) demonstrating higher correlation and better agreement with FIDDLE. See text for details.

Patients

We enrolled 31 subjects (20 with MI, 11 normal controls), all of whom successfully completed MRI. No subject was excluded based on poor image quality. The SAR for FIDDLE was 0.76±0.15W/kg at 1.5T and 1.97±0.27W/kg at 3T, and there were no issues with exceeding FDA SAR constraints in any patient. Table 2 shows the baseline clinical characteristics. Among patients with MI, 10 were imaged ≤2-weeks post-MI and 10 were imaged >2 weeks post-MI (median 24 weeks). In all 20 patients with MI, the infarcted region on FIDDLE matched the perfusion territory of the infarct-related-artery identified by X-ray coronary angiography. There was no evidence of “slow blood flow” artifacts in the LV cavity in any of the FIDDLE images.

Table 2.

Patient Demographics

| Characteristics | MI patients (n=20) |

Normal controls (n=11) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs | 56±14 | 32±11 |

| Female Gender | 8 (40%) | 4 (44%) |

| Risk Factors | ||

| Hypertension | 12 (60%) | 3 (33%) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 14 (70%) | 0 (0%) |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 8 (40%) | 0 (0%) |

| Smoking | 8 (40%) | 0 (0%) |

| Family History of CAD | 8 (40%) | 1 (11%) |

| ECG at MI admission | ||

| ST-segment elevation | 13 (65%) | — |

| Non-ST-segment elevation | 7 (35%) | — |

| Troponin T (ng/ml) | 7.6 IQR (4.0, 11.9)* | — |

| Infarct Related Artery | ||

| LAD | 10 (50%) | — |

| LCx | 7 (35%) | — |

| RCA | 3 (15%) | — |

Troponin I was used in the diagnosis of acute MI in 4 patients.

CAD, coronary artery disease, IQR, interquartile range; LAD, left anterior descending; LCx, left circumflex; MI, myocardial infarction; RCA, right coronary artery; yrs, years.

Fig 5a shows typical images in MI patients in whom both FIDDLE and DE-MRI clearly depicted infarcted regions. Fig 5b shows images in five patients (3 with MI, 2 controls without MI) in whom the diagnosis of MI was ambiguous on DE-MRI. With FIDDLE, patients with MI were easily discriminated from the controls.

Figure 5. Patient examples of FIDDLE and DE-MRI.

a. Images in four patients in whom the infarct is clearly delineated on both FIDDLE and DE-MRI. Of note, there are no “slow flow” artifacts in any of the short or long-axis FIDDLE images.

b. Images from three patients with MI and two controls. In patients 5 and 6, there is possibly anteroseptal wall hyperenhancement on DE-MRI (red arrows). However, FIDDLE shows no hyperenhancement and correctly identifies patient 6 as a normal control. In patients 7 and 8, FIDDLE identifies that patient 8 is a normal control. In patient 9, FIDDLE clearly demonstrates not only a subendocardial infarct in the anterior wall, but also extension into the inferoapical wall (blue arrows).

Overall, the diagnostic performance in patients was similar to that observed in canines (Table 1), and there were no differences in the findings at 3T (n=15) versus 1.5T (n=16). Accuracy was higher for FIDDLE than DE-MRI (100% vs 84%). Also there were trends towards higher sensitivity (100% vs 85%) and higher specificity (100% vs 82%).

The CNR between infarct and normal myocardium was measured in 11 additional patients, all of whom had a clearly identifiable infarct on DE-MRI. At 1.5T, the mean CNRs for DE-MRI and FIDDLE were 11.0±5.8 and 9.5±3.5, respectively, reflecting a 14% loss on average for FIDDLE. At 3T, CNRs were 11.3±4.1 and 10.1±2.6, respectively, representing a 10% loss on average.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we introduce FIDDLE, a new MRI technique that allows visualization of myocardial tissue contrast-enhancement while simultaneously rendering the blood-pool black. FIDDLE was characterized in simulations and validated in a canine model of MI with direct reference to pathology. The clinical performance of FIDDLE was demonstrated in patients with documented MI and known coronary artery anatomy.

FIDDLE provided superior diagnostic performance compared with conventional DE-MRI, the current in-vivo reference standard for the imaging diagnosis of MI. In canines, sensitivity and accuracy were significantly higher for FIDDLE, while specificity was excellent for both techniques. Findings were similar in patients, where FIDDLE had a diagnostic accuracy of 100% versus 84% for DE-MRI.

FIDDLE overcomes an important intrinsic limitation of conventional DE-MRI. Since infarcted myocardium and adjacent blood-pool have comparable T1 values following contrast media administration,9 image intensities are often similar on DE-MRI.3 As a result, distinguishing hyperenhanced infarcted tissue from bright blood-pool may be difficult unless the infarct is fully transmural or nearly so. This may explain why the diagnostic performance of DE-MRI is reduced in some cohorts, such as patients with non-Q-wave MI who are more likely to have infarcts that are subendocardial.4 Consistent with this notion, in the current study when only subendocardial infarcts were considered, the sensitivity of DE-MRI dropped to 80% whereas it remained high for FIDDLE at 98%.

Although this may suggest that the primary advantage of FIDDLE is in patients with small infarcts, we observed that some infarcts missed by DE-MRI can be relatively large. An example of such a case is shown in Fig 5b (patient 9), who had an infarct size of 14% of LV mass as measured by FIDDLE. This demonstrates that an infarct can be extensive in the circumferential direction but still be subendocardial and missed by DE-MRI.

Even when infarction was identified by DE-MRI, the data indicate that it was rare to visualize the entire length of the MI endocardial border, in contradistinction to FIDDLE images for which the entire border was always visualized. Hence, infarct size measurements were more robust with FIDDLE than with DE-MRI; in comparison to pathology, there was reduced bias and smaller 95% limits-of-agreement with FIDDLE.

Several approaches for improving the discrimination of blood-pool and infarcted myocardium have been proposed. Some are dependent on the motion of blood in the LV cavity, either as bulk flow or diffusion.17 These techniques are limited in that “slow blood flow” artifacts, which are bright and difficult to distinguish from subendocardial infarction, are likely to occur in patients with ventricular dysfunction. Unlike these approaches, FIDDLE employs a novel method which is not dependent on the movement of blood. In the current study, there was no evidence of “slow blood flow” artifacts in any of the FIDDLE images, including long-axis views. Nonetheless, it should be noted that inhomogeneities in B1 and B0 may affect the uniformity of dark-blood preparation, particularly at 3T.

Other techniques have been proposed that are not dependent on blood flow. Liu et al.18 describe a technique that combines T2 and T1 weighting to improve the delineation between infarcted myocardium and ventricular blood-pool. Peel et al.19 describe a method that uses a dual IR-prepulse to suppress blood-pool signal. Although contrast between infarcted myocardium and blood-pool may be improved with these techniques, the level of blood suppression may be minimal. Unlike FIDDLE, none of these methods produce black-blood images. Specifically, these methods result in images in which blood-pool signal is higher than viable myocardium, hence, an endocardial layer that is partially infarcted may still be difficult to distinguish from blood-pool.

FIDDLE was designed to be flexible and modular in order to accommodate different preparation pulses, execution order, and readout type. Since its first description by our group in 2011,6 some pilot studies with variants of FIDDLE have been reported.8,16,20 Muscogiuri et al.20 used a T2-rho-prep variant of FIDDLE and reported that this technique detected more patients with infarction than DE-MRI in patients with suspected MI. They speculated that one possible benefit of a T2-rho-prep over an MT-prep is that the latter may have high energy requirements. However, with the sequence described herein, we did not encounter this problem. There were no issues with exceeding SAR constraints in any of the patients scanned at 1.5T or 3T.

Kellman et al.16 describe a T2-prep variant of FIDDLE, albeit the order of the T2- and IR-preparations are reversed. This variant also combines single-shot SSFP readout with motion correction in order to allow imaging during free-breathing. In a pilot study of 30 patients in which 1 slice location was imaged per patient with both dark-blood and bright-blood techniques, they report that the conspicuity of subendocardial fibrosis was improved by dark-blood imaging. Unfortunately, there was no reference standard for the diagnosis of fibrosis, hence the diagnostic accuracy of dark-blood imaging was not assessed. In comparison, the current study is the first to validate dark-blood delayed-enhancement imaging (of any type) directly against a pathology-based reference standard. Additionally, high diagnostic accuracy was verified in patients, and imaging in patients was performed at both 1.5T and 3T field strengths to increase the generalizability of the findings.

Recently, our group has compared a T2-prep variant of FIDDLE with MT-prep FIDDLE.8 We observed that T2-prep FIDDLE was more likely to result in artifacts in the left atrial cavity which appeared to be secondary to non-uniform magnetization preparation, particularly at 3T. Additionally, T2-prep FIDDLE occasionally resulted in different levels of blood-pool suppression in the right versus left-sided cardiac chambers. This is because deoxygenated blood in the right-sided chambers has shorter T2 than the oxygenated blood in the left-sided chambers. Although these findings suggest potential advantages with MT-prep, these are only preliminary data; further investigation is needed.

From an efficiency standpoint, FIDDLE is essentially identical to DE-MRI. No additional post processing or image registration is required and image reconstruction is completed at the time of image acquisition. The same dose of contrast media is used, and imaging can be performed at the same time-point after contrast administration. Moreover, spatial resolution, temporal resolution, and breath-hold duration (8–10secs) were identical in this study. In other words, the implementation of FIDDLE reported herein was designed to be a ‘drag and drop’ replacement for conventional DE-MRI.

Additionally, setting the inversion time (TI) for FIDDLE is straightforward. One simply examines the image intensity of the blood-pool: if the blood-pool is not black the TI needs to be reduced, whereas if the blood-pool is black then the TI should be increased to the maximum value that still results in black-blood. In general, 1–2 scout images are sufficient to find the optimal TI, but nonetheless this is a limitation that can lengthen scan time. Given its diagnostic performance and ease of use, FIDDLE has become a core component of our clinical cardiac MR exam, and we are currently using it daily at both 1.5 and 3T.

There are several implications of our study. Our data suggest that, even in the modern era, the imaging diagnosis of MI can be difficult, and that new methods may improve decision making, risk stratification, and management. Moreover, the data suggest that the most important source of variability in infarct size measurements by DE-MRI is the uncertainty in identifying the border between infarction and LV blood-pool. The reduced variability associated with FIDDLE is expected to be important in clinical trials that employ infarct size as a surrogate endpoint. In the current study, patients with known MI were enrolled in order to validate FIDDLE. In the future, studies in patients with suspected rather than clinically confirmed MI will be needed. It should be noted that FIDDLE provides a general approach to improve contrast-enhanced MRI of tissue pathology by separating parenchymal contrast-enhancement from blood-pool enhancement. Hence, the technique may have broad applicability in visualizing other pathologies throughout the heart and cardiovascular system (e.g. atrial fibrosis, aortopathies, etc). This will need to be evaluated in future investigations.

In summary, our results demonstrate that FIDDLE provides superior diagnostic performance than the current in-vivo reference standard for the imaging diagnosis of MI.

Clinical Perspectives.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE

FIDDLE, a novel flow independent dark-blood delayed-enhancement MRI technique, is described and validated against pathology in an animal model of myocardial infarction. Comparisons with conventional delayed-enhancement MRI, the current in-vivo reference standard for imaging myocardial infarction, demonstrate that FIDDLE has higher diagnostic accuracy and provides more accurate infarct size measurements. Findings were replicated in patients, where FIDDLE also showed higher accuracy than delayed-enhancement MRI for the diagnosis of myocardial infarction.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK

Future studies will further elucidate the role of FIDDLE in identifying infarction, fibrosis, or scarring in patients with coronary artery disease and non-ischemic cardiomyopathies. FIDDLE may provide a new avenue to explore pathologies involving the right ventricle, atria, and other tissues where blood pool enhancement may mask tissue enhancement, as well as improve the quantification of infarct size, which is an important surrogate endpoint in clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

US National Institute of Health grant NIH-NHLBI R01-HL64726 (R.J. Kim). There was no industry support for this study.

Abbreviations

- CNR

contrast-to-noise ratio

- DE-MRI

delayed-enhancement magnetic resonance imaging

- FIDDLE

flow-independent dark-blood delayed enhancement

- IR

inversion-recovery

- LV

left ventricle

- MT-prep

magnetization transfer preparation

- M0

baseline longitudinal magnetization

- Mz

blood or tissue magnetization

- SAR

specific absorption rate

- SNR

signal-to-noise ratio

- SSFP

steady state free precession

- T

Tesla

- TI

inversion time

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

Drs. R.J. Kim and R.M. Judd are inventors on a US patent on delayed-enhancement MRI owned by Northwestern University. Dr. R.J. Kim is an inventor on a US patent on flow independent dark-blood delayed enhancement MRI owned by Duke University. Dr. W. Rehwald is employed by Siemens Medical Solutions. The other authors report no conflicts.

References

- 1.Hochholzer W, Buettner HJ, Trenk D, Laule K, et al. New definition of myocardial infarction: impact on long-term mortality. Am J Med. 2008;121:399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim HW, Farzaneh-Far A, Kim RJ. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in patients with myocardial infarction: current and emerging applications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;55:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sievers B, Elliott MD, Hurwitz LM, Albert TS, et al. Rapid detection of myocardial infarction by subsecond, free-breathing delayed contrast-enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Circulation. 2007;115:236–44. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.635409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim RJ, Albert TS, Wible JH, Elliott MD, et al. Performance of delayed-enhancement magnetic resonance imaging with gadoversetamide contrast for the detection and assessment of myocardial infarction: an international, multicenter, double-blinded, randomized trial. Circulation. 2008;117:629–37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.723262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simonetti OP, Finn JP, White RD, Laub G, et al. "Black blood" T2-weighted inversion-recovery MR imaging of the heart. Radiology. 1996;199:49–57. doi: 10.1148/radiology.199.1.8633172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim RJ. Blood signal suppressed enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. 9,131,870 B2. US Patent. 2015 Sep 15;

- 7.Kim HW, Rehwald W, Wendell DC, Jenista ER, et al. Black-Blood Contrast-Enhanced MRI: Validation of a Novel Technique for the Diagnosis of Myocardial Infarction. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Toronto, Ontario, CA #0662. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jenista E, Wendell DC, Kim HW, Rehwald WG, et al. Comparison of T2-preparation and magnetization-transfer preparation for black blood delayed enhancement. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2016;18:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JJ, Liu S, Nacif MS, Ugander M, et al. Myocardial T1 and extracellular volume fraction mapping at 3 tesla. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2011;13:75. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-13-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim HW, Van Assche L, Jennings RB, Wince WB, et al. Relationship of T2-Weighted MRI Myocardial Hyperintensity and the Ischemic Area-At-Risk. Circ Res. 2015;117:254–65. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.305771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reimer KA, Lowe JE, Rasmussen MM, Jennings RB. The wavefront phenomenon of ischemic cell death. 1. Myocardial infarct size vs duration of coronary occlusion in dogs. Circulation. 1977;56:786–94. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.56.5.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Position of the American Heart Association on the use of research animals. Circ Res. 1985;57:330–1. doi: 10.1161/01.res.57.2.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim RJ, Fieno DS, Parrish TB, Harris K, et al. Relationship of MRI delayed contrast enhancement to irreversible injury, infarct age, contractile function. Circulation. 1999;100:1992–2002. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.19.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schulz-Menger J, Bluemke DA, Bremerich J, Flamm SD, et al. Standardized image interpretation and post processing in cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2013;15:35. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-15-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D'Agostino RB, Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, Wolf PA, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:743–53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kellman P, Xue H, Olivieri LJ, Cross RR, et al. Dark blood late enhancement imaging. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2016;18:77. doi: 10.1186/s12968-016-0297-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farrelly C, Rehwald W, Salerno M, Davarpanah A, et al. Improved detection of subendocardial hyperenhancement in myocardial infarction using dark blood-pool delayed enhancement MRI. AJR. 2011;196:339–48. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu CY, Wieben O, Brittain JH, Reeder SB. Improved delayed enhanced myocardial imaging with T2-Prep inversion recovery magnetization preparation. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;28:1280–6. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peel SA, Morton G, Chiribiri A, Schuster A, et al. Dual inversion-recovery mr imaging sequence for reduced blood signal on late gadolinium-enhanced images of myocardial scar. Radiology. 2012;264:242–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12112004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muscogiuri G, Rehwald WG, Schoepf UJ, Suranyi P, et al. T(Rho) and magnetization transfer and INvErsion recovery (TRAMINER)-prepared imaging: A novel contrast-enhanced flow-independent dark-blood technique for the evaluation of myocardial late gadolinium enhancement in patients with myocardial infarction. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2016 doi: 10.1002/jmri.25498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]