Abstract

Iconic memory is characterized by its large storage capacity and brief storage duration, whereas visual working memory is characterized by its small storage capacity. The limited information stored in working memory is often modeled as an all-or-none process in which studied information is either successfully stored or lost completely. This view raises a simple question: If almost all viewed information is stored in iconic memory, yet one second later most of it is completely absent from working memory, what happened to it? Here, I characterized how the precision and capacity of iconic memory changed over time and observed a clear dissociation: Iconic memory suffered from a complete loss of visual items, while the precision of items retained in memory was only marginally affected by the passage of time. These results provide new evidence for the discrete-capacity view of working memory and a new characterization of iconic memory decay.

Keywords: iconic memory, sensory memory, visual working memory, discrete capacity

Iconic memory allows us to retain large amounts of visual information over brief periods of time following the removal of a visual stimulus (Averbach & Coriell, 1961; Sperling, 1960). The rapid loss of information from iconic memory over time is ubiquitously referred to as a “gradual decay” or “gradual fading,” which leads to a decrease in “iconic legibility” (e.g., Gegenfurtner & Sperling, 1993). These descriptions are often elaborated with analogies, such as one from Coltheart (1980), who likens the decay to “a photograph [that] loses contrast over time” (p. 222). However, to my knowledge, this assumption that iconic memory is analogue in nature and gradually decaying has not been directly tested, and it is not the only possibility. In particular, many theories posit that some of the information in iconic memory is transferred to a more durable but capacity-limited visual working memory system, where it can be reliably maintained and manipulated (e.g., Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1968). This subsequent working memory system is often characterized as an all-or-none store that holds accurate information about only a few discrete items (Cowan, 2001; Luck & Vogel, 1997; Rouder et al., 2008; Zhang & Luck, 2008). Moreover, working memory has been shown to lose entire items over time, while information about successfully retained items does not decay (Zhang & Luck, 2009). Here, I examined whether iconic memory exhibits a gradual decay, as is often assumed, or whether information loss from iconic memory is item-based and discrete in nature, as it is for working memory.

To examine how information degrades in iconic memory, I measured the quantity and quality of information in iconic memory at various points in time following visual stimulation. I directly followed the work of Zhang and Luck (2009), who assessed decay in working memory over periods of seconds, and considered two ways in which information might decay in iconic memory over the few hundred milliseconds following perception. According to the theory of gradual decay, the precision with which an item’s features are represented in iconic memory degrades gradually over time, such as by a gradual loss of stimulus contrast or an increase in noise (Figs. 1a–1c). Such a gradual decay mechanism characterizes the standard view of iconic memory. However, an alternative possibility is that iconic memories suffer a sudden death, whereby information about an item is retained with high precision until some point at which knowledge about the item vanishes completely from memory (Fig. 1e–1g).

Fig. 1.

Gradual-decay and sudden-death models of color memory decay. In the gradual-decay model (top row), representations of perceived items (a) become weaker over the course of iconic memory (b), such that many items in working memory (c) contain very little stimulus information. As information decays, behavioral accuracy in reporting the color of an item would become less precise over time (d). In the sudden-death model (bottom row), perceived items (e) vanish entirely from memory over the course of iconic memory (f), such that only a few items remain in working memory (g). The sudden-death model predicts more frequent pure guessing behavior as more items vanish, with no loss of precision for those items still in memory (h).

Previous studies of iconic memory have been unable to adjudicate between gradual decay and sudden death, in part because they measured memory for highly complex stimuli such as letters. In these studies, the iconic trace of a letter might decay gradually, but letter report can remain successful until the decay has reached some lower threshold at which it is no longer identifiable. Here, I instead tested iconic memory by asking participants to report the precise color or orientation of a previously viewed item. In this case, a gradual decay of iconic memory should produce reports that become less and less accurate as the iconic delay period increases (Fig. 1d). Alternatively, if iconic memories suffer a sudden death, then the probability of complete guessing should increase as more items vanish from memory, but reports for items still in memory should remain highly accurate (Fig. 1h). Analyzing these feature-report data with formal models (Zhang & Luck, 2008, 2009) allows one to separately measure the amount of gradual decay and sudden death in iconic memory. I found strong evidence that visual memories for an item’s color and orientation die a complete and sudden death over the time course of iconic memory, while the precision of items successfully retained in memory remains largely unchanged. These results provide support for the idea that whatever information makes it to working memory is also all or none—as predicted by discrete-capacity models—and challenge the conventional characterization of iconic memory as a gradually decaying trace.

Method

Participants

Participants in Experiments 1a and 2a completed a single 1-hr session in exchange for credit toward a course requirement. Data were not considered for participants who were clearly not following task instructions (10 total; see the Supplemental Material available online); therefore, 55 and 42 participants were included in the main analyses of Experiments 1a and 2a, respectively. In Experiments 1b and 2b, 8 participants completed ten 1-hr sessions on 10 different days in exchange for monetary compensation ($10/hr). All experiments were approved by the Mississippi State University Institutional Review Board.

Stimuli and design

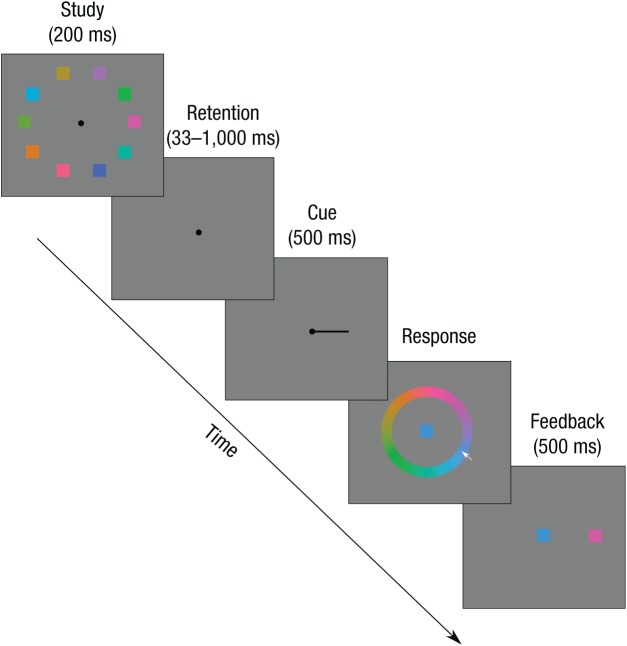

Iconic memory has typically been studied using complex visual stimuli such as letters. A recent study has identified very similar decay characteristics for simple visual features such as color and orientation (Bradley & Pearson, 2012). However, the authors were unable to distinguish between sudden death and gradual decay because of the two-alternative forced-choice paradigm employed. Here, I utilized a feature-report paradigm, which allows sudden death and gradual decay to be estimated separately (Zhang & Luck, 2008). Figure 2 shows the trial structure for Experiments 1a and 1b. Participants were shown 10 colored squares (1° width) for 200 ms on a gray background (50% luminance), spaced evenly on an invisible circle (3.5° eccentricity) around a central fixation point (0.4° diameter). On each trial, colors were chosen randomly from 180 colors located along a circle in the Lab color space (luminance = 70, radius = 40, center a = −10, b = 30) with the restriction that adjacent items differed in color by at least 40°. Following a variable retention interval that included only the black fixation point, a black line originating from fixation (1.5° long) pointed to 1 of the 10 locations that were previously occupied by a color stimulus. Participants then used the computer mouse to report the previously shown color at the probed location on a centrally located color wheel. After they responded by clicking a mouse button, participants saw feedback simultaneously showing the reported color at fixation and the studied color at its original studied location (500 ms, followed by a 1-s intertrial interval).

Fig. 2.

Structure of a trial in Experiments 1a and 2a.

Participants in Experiment 1a completed 160 experimental trials at retention intervals of 33, 200, and 500 ms. In Experiment 1b, 8 participants completed 300 trials at retention intervals of 33, 66, 100, 150, 233, 383, 617, and 1,000 ms over the course of five experimental sessions, in order to more accurately characterize the iconic decay function. Experiments 2a and 2b were identical to Experiments 1a and 1b, respectively, with the exception that the orientation of Gabor patches was studied (90% contrast, 3 cycles/° spatial frequency, 1.5° maximum diameter with σ = .33°, producing a ~1° visual grating), and after the retention interval and probe, participants reported the orientation of the probed grating by rotating a Gabor patch using the mouse. In Experiment 2a, the response grating appeared at the location of the original probed grating, and following a response, a feedback bar indicated relative performance by its color and height. In Experiment 2b, the response grating was located at fixation, and following the response, feedback was provided by simultaneously showing the reported orientation at fixation and the studied orientation at its original studied location. In Experiment 2b, the same 8 participants from Experiment 1b completed five sessions of the orientation task. Each session of all experiments began with 20 practice trials (50 for Experiment 2a).

Model estimation and comparison

All models were fitted to individual participant data using maximum likelihood estimation. Null-hypothesis significance tests were used to assess condition effects on estimated parameters. In addition, formal model comparisons were performed using the Akaike information criterion (AIC). Results were similar if models were instead compared using the Bayesian information criterion (BIC); however, recent work suggests that the AIC statistic provides better model recovery for models that are similar to those considered here (van den Berg, Awh, & Ma, 2014).

The AIC statistic was used in two ways to compare models. First, AIC scores were summed over participants, and the summed values were compared across a given set of models. This approach has the desirable property of assuming that all participants follow the same model. However, combining scores in this way is akin to treating participants as fixed rather than random effects, such that the results may not be generalizable to the population. Therefore, a more conservative approach was also taken by counting the number of participants for which one model provided a better fit than another (as evidenced by a lower AIC score). A majority of participants being best fitted by the same model was taken as evidence for that model’s superior performance.

Results

Sudden death and gradual decay

According to the Zhang & Luck (2008) mixture model, either a response results from a representation stored in memory and follows a von Mises distribution centered on the studied stimulus value, or it is a pure guess and follows a uniform distribution. The model has two free parameters: the probability of guessing, which is proportional to the number of items that are successfully stored in memory (capacity), and the accuracy of responses that result from items successfully stored in memory (precision). In the full model, both capacity and precision are free to vary across retention intervals. Sudden death predicts lower capacity estimates with increasing retention interval, reflecting a higher proportion of pure guessing responses. Alternatively, gradual decay predicts lower precision values across retention intervals, implying that the quality of the representations degrades but that information does not vanish entirely.

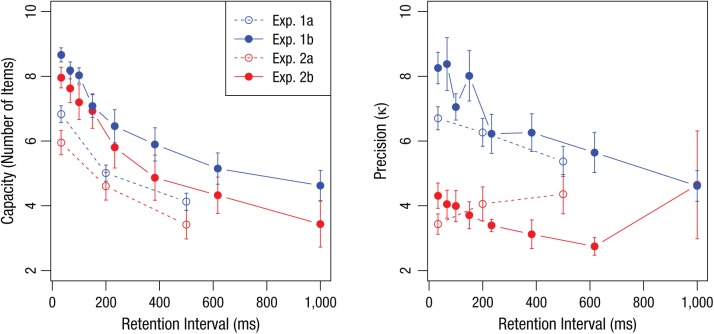

Figure 3 shows estimates of capacity (left) and precision (right) from these full model fits to each experiment. Mean estimates of capacity decreased monotonically with retention interval in each of the four experiments. Repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) on capacity estimates for each experiment suggest that capacity varied as a function of retention interval in Experiment 1a, F(2, 108) = 60.07, p < .001; Experiment 1b, F(7, 49) = 53.70, p < .001; Experiment 2a, F(2, 82) = 12.62, p < .001; and Experiment 2b, F(7, 49) = 37.63, p < .001. Alternatively, estimates of precision show much less dependence on retention interval. ANOVAs on estimates of precision failed to reveal significant relationships between precision and retention interval in Experiment 1a, F(2, 108) = 2.73, p = .07; Experiment 2a, F(2, 82) = 0.96, p = .39; or Experiment 2b, F(7, 49) = 1.07, p = .40. A significant relationship was observed in Experiment 1b, in which color was studied across eight retention intervals, F(7, 49) = 8.06, p < .001. Follow-up Bonferroni-corrected t tests indicated that this effect was largely driven by significant differences between the longest retention interval and the two shortest intervals.

Fig. 3.

Estimates of capacity (left) and precision (right) from the full mixture model as a function of retention interval for each of the four experiments. Error bars denote standard errors.

Across the four experiments, results from fitting the full model suggest that capacity decreased substantially as the retention interval increased (average ηp2 = .62), whereas the effect of retention interval on precision was modest or absent (average ηp2 = .18). Simulation studies suggest that these experimental designs and analyses are highly capable of detecting effects on precision should they exist, which suggests that the failure to observe effects in precision was not due to underpowered designs (see the Supplemental Material for details). However, the analysis of full model parameters with ANOVAs may be inappropriate for several reasons. In particular, estimates of precision tend to have more variance in conditions with high guessing rates; specifically, the homogeneity of variance assumption of the ANOVA is not likely to hold. Additionally, the claim that precision is largely invariant across retention intervals relies on an acceptance of the null hypothesis.

To circumvent these shortcomings of null-hypothesis testing, I fitted restricted versions of the discrete-capacity model and compared them with the full model. In the fixed-capacity model, capacity was forced to be identical across retention intervals, and only precision was free to vary. This fixed-capacity model performed worse than the full model for 43 of 55 participants in Experiment 1a (ΔAIC = 403), 8 of 8 in Experiment 1b (ΔAIC = 477), 25 of 42 in Experiment 2a (ΔAIC = 13), and 7 of 8 in Experiment 2b (ΔAIC = 137). These results again suggest that capacity decreases over the course of iconic memory decay for both color and orientation information.

In order to assess whether precision varied across retention intervals, I fitted a fixed-precision model, in which capacity was free to vary across retention intervals but precision was forced to be constant. This fixed-precision model performed better than the full model for 45 of 55 participants in Experiment 1a (ΔAIC = 78), 37 of 42 participants in Experiment 2a (ΔAIC = 83), and 6 of 8 participants in Experiment 2b (ΔAIC = 23). However, the restricted-precision model was rejected in favor of the full model for 6 of 8 participants in Experiment 1b (ΔAIC = 7). This small difference in AIC values indicates that the models were performing almost equally well. Nonetheless, the slightly better fit of the full model is congruent with the ANOVA result of a significant effect of retention interval on precision in this experiment. Across the four experiments, however, the fixed-precision model provided a similar or better account of the data than the full model, suggesting that the retention interval had little to no effect on precision.

The results across four experiments imply that iconic memory capacity decreases precipitously as the retention interval increases, whereas the precision of those representations still in memory remains largely unchanged or decreases slightly. This pattern is squarely in line with the predictions of a sudden-death decay process in iconic memory, in which information about an item in iconic memory is maintained with high precision until it vanishes abruptly and completely. In the following sections, I consider possible extensions and simplifications of this sudden-death model and compare it with potential alternative accounts.

Continuous-resource models

The ideas of sudden death and gradual decay are predicated on the assumption that memory follows the discrete-capacity mixture model. A central assumption of this model is that some information is completely absent from memory, and evidence for such complete information loss in working memory has been purportedly shown using a variety of approaches (Donkin, Nosofsky, Gold, & Shiffrin, 2013; Rouder et al., 2008; Thiele, Pratte, & Rouder, 2011; Zhang & Luck, 2008). However, some researchers have suggested that, instead, all visual information is always retained in memory to some degree (Bays & Husain, 2008; van den Berg, Shin, Chou, George, & Ma, 2012; Wilken & Ma, 2004). According to this continuous-resource view, memory representations are degraded at high set sizes because a limited memory resource must be divided across a large amount of information, but previously viewed items are never completely absent from memory. These models have no mechanism for pure guessing, and they therefore rule out sudden death a priori. Here, I consider the possibility that continuous-resource models might provide a more accurate view of iconic memory decay than the sudden-death mixture model.

The simplest continuous-resource models are essentially signal detection models (Wilken & Ma, 2004) and predict that longer retention intervals must lead to worsening precision. Such a declining-precision (fixed-capacity) model was already ruled out. However, contemporary resource models additionally allow memory precision to vary randomly from trial to trial, such as from variability in attention (Fougnie, Suchow, & Alvarez, 2012; van den Berg et al., 2012). Following this work, I constructed such a model by assuming that responses followed a wrapped normal distribution in which precision values arose from a gamma distribution parameterized by its mean and shape. Several variations of this model were considered (see the Supplemental Material), but here I consider the continuous-resource model, in which mean precision varied freely with the retention interval, and the shape of the precision distribution was fixed across retention intervals. This model is similar in complexity to the discrete-capacity sudden-death model, in which guess rates were free to vary across retention interval but precision was fixed. Comparing these models suggests that the sudden-death model provides a better account of the data for 45 of 55 participants in Experiment 1a (ΔAIC = 500), 5 of 8 participants in Experiment 1b (ΔAIC = 129), 37 of 42 participants in Experiment 2a (ΔAIC = 228), and 8 of 8 participants in Experiment 2b (ΔAIC = 219). These results again suggest that the decay in iconic memory is best characterized by an increasing rate of pure guessing and not simply a decrease in memory precision.

A key feature of continuous-resource models is their ability to account for trial-to-trial variability in precision, a mechanism which is not present in typical discrete-capacity models. However, much of the variability in working memory performance appears to stem from low-level stimulus properties, such as differences in visual sensitivity to different colors (Bae, Allred, Wilson, & Flombaum, 2014) or different orientations (Pratte, Park, Rademaker, & Tong, 2017). Because both continuous-resource and discrete-capacity theories can anticipate trial-to-trial variability in precision, a meaningful statistical comparison requires that both mathematical models can account for trial-to-trial variability in precision. I therefore constructed a version of the sudden-death discrete-capacity model in which guess rate varied across retention intervals and mean precision was fixed, but which additionally allowed for latent trial-to-trial variability in precision (see the Supplemental Material). This sudden-death model with latent variability in precision clearly outperformed the fixed-shape continuous-resource model for 52 of 55 participants in Experiment 1a (ΔAIC = 567), 8 of 8 participants in Experiment 1b (ΔAIC = 326), 32 of 42 participants in Experiment 2a (ΔAIC = 163), and 8 of 8 participants in Experiment 2b (ΔAIC = 209). Therefore, once both continuous-resource and sudden-death models were able to account for trial-to-trial variability in precision, the sudden-death discrete-capacity model provided a far more accurate account of iconic memory performance.

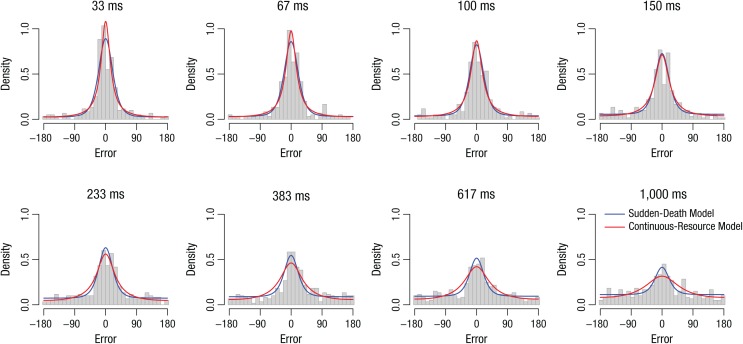

Figure 4 shows response errors for 1 participant in Experiment 1b. Predictions of the sudden-death mixture model with latent variable precision and the continuous-resource model are overlaid. This participant’s data are typical of other participants and other experiments in this article and demonstrate that both models generally accounted for the data very well. However, whereas the models provided almost equivalent fits at shorter retention intervals, as retention intervals increased and performance worsened, the continuous-resource model systematically failed to capture the very heavy tails of the distribution. Moreover, in attempting to fit the data at a 1-s retention interval, the continuous-resource model specified that precision was so low that on 56% of trials, responses would be ±45° or more from the studied color. Although it is technically possible to attribute such poor performance to a preponderance of trials with extremely low precision (e.g., calling a pink stimulus blue), it seems more reasonable that this extremely poor performance reflects pure guessing, as specified in the discrete-capacity model (see also Adam, Vogel, & Awh, 2017).

Fig. 4.

Histograms of response errors in color memory from 1 participant in Experiment 1b. Blue lines are from the sudden-death discrete-capacity model with latent variable precision; red lines are from the continuous-resource model in which mean precision varies across retention interval and the shape of the distribution on precision is fixed.

Exponential decay

Several studies have suggested that information in sensory memory decays at an exponential rate (e.g., Bradley & Pearson, 2012), although other functions have been proposed (e.g., Loftus, Duncan, & Gehrig, 1992). Whereas the models considered so far allow for arbitrary decay profiles in capacity or precision, these parameters may instead be constrained to follow an exponential function of retention interval (see the Supplemental Material for details). For example, the sudden-death model was amended such that guess rate decreased with retention interval according to a three-parameter exponential function. It was not possible to assess this model in Experiments 1a and 2a, as these included only three retention intervals. However, this constrained model outperformed the unconstrained sudden-death model for 7 of 8 participants in Experiment 1b (ΔAIC = 28) and for 6 of 8 participants in Experiment 2b (ΔAIC = 22). When variability in precision was included in this model and compared with the sudden-death variable-precision model without exponential decay, the exponential function was supported for 6 of 8 participants in Experiment 1b (ΔAIC = 22) and 6 of 8 participants in Experiment 2b (ΔAIC = 21). Although more work is needed to explore the precise parametric form of decay, these results suggest that iconic memory can be explained by a surprisingly simple model in which the probability of guessing increases exponentially with retention intervals, while precision remains largely constant.

Swap errors

It has been suggested that many of the random guesses in working memory in fact reflect swap errors, in which participants mistakenly report the feature value of one of the nontarget items in the study array (Bays, Catalao, & Husain, 2009). The degree to which participants make such nontarget responses in working memory tasks is not clear, with some studies reporting a large number (Bays et al., 2009), but others, including a recent meta-analysis of 10 studies, suggesting that such responses are rare (van den Berg et al., 2014). In addition, it has been shown that sudden death in working memory is due to an increase in pure guessing over time rather than to an increase in swap errors (Donkin, Nosofsky, Gold, & Shiffrin, 2015). To assess nontarget responses in iconic memory, I fitted a version of the full mixture model that additionally included free swap-rate parameters for each retention interval (see the Supplemental Material for details).

The addition of swap errors to the full mixture model improved model fit in both Experiment 1a (29 of 55 participants; ΔAIC = 143) and Experiment 1b (8 of 8 participants; ΔAIC = 238), but the model without swap errors performed somewhat better in both Experiment 2a (35 of 42 participants; ΔAIC = 144) and Experiment 2b (7 of 8 participants; ΔAIC = 17). Critically, restricting precision in this swap model to be constant across retention intervals produced a better fit in Experiment 1a (44 of 55 participants; ΔAIC = 72), Experiment 2a (38 of 42 participants; ΔAIC = 79), and Experiment 2b (6 of 8 participants; ΔAIC = 21), with mixed results in Experiment 1b (4 of 8 participants; ΔAIC = 2.9 in favor of the unrestricted model). When the model was further restricted so the proportion of nontarget responses that were swap errors was fixed across retention intervals, it also outperformed the full swap model in Experiment 1a (50 of 55 participants; ΔAIC = 206), Experiment 1b (7 of 8 participants; ΔAIC = 54), Experiment 2a (40 of 42 participants; ΔAIC = 197), and Experiment 2b (7 of 8 participants; ΔAIC = 78) and often outperformed the fixed-precision models without swap errors (see Table S1 in the Supplemental Material). This model suggests that swap errors made up 35%, 48%, 15%, and 19% of nontarget responses in Experiments 1a, 1b, 2a, and 2b, respectively. Taken together, these results again suggest a fixed-precision model, but one in which a proportion of nontarget responses are centered around nontarget items. Further work is needed to understand the nature of this behavior, and examining how swap errors develop over the course of iconic memory decline may provide a new avenue for understanding their role in working memory tasks.

Discussion

Iconic memory decay is typically described as a gradual fading of information over time. This characterization is ubiquitous, perhaps because it seems so reasonable: Whether neural firing rates gradually decrease over time or neural interference increases, one might expect the information contained in iconic memory to degrade gradually. However, across four experiments, I showed that the visual information available in iconic memory does not decay gradually. Instead, knowledge about the color and orientation of objects seems to vanish from memory in a discrete, all-or-none fashion during the few hundred milliseconds following visual perception.

Whereas the probability of an item dying a sudden death increased precipitously during the retention interval, the precision of items successfully retained in memory did not significantly degrade over time in three of four experiments. If the results are considered across the four experiments, the model with fixed precision outperformed the full model with free precision for 90 out of 113 participants (80%), as assessed with AIC scores. When these models were compared using the more conservative BIC statistic, the fixed-precision model provided a better fit than the full model for 112 out of 113 participants (99%). These results include experiments with large sample sizes but only three retention intervals, and experiments with a large number of samples per participant across several retention intervals. The lack of appreciable precision effects is therefore consistent across different experimental designs and across orientation and color memory. This robust and replicable null effect suggests that visual information about an item is retained with high precision in iconic memory until some point at which it vanishes completely. There was, however, some evidence for declining precision in Experiment 1b. It is possible that with more data or different stimuli, such effects would become prominent. In particular, some manipulations have been shown to influence the precision but not the capacity of working memory, such as adding external noise (Zhang & Luck, 2008) or inverting to-be-remembered faces (Lorenc, Pratte, Angeloni, & Tong, 2014). Exploring how such manipulations affect the precision of iconic memory may help clarify the role of precision decrements in iconic decay (see also Cappiello & Zhang, 2016).

Visual memory during the brief moments following perception is often characterized by two distinct memory systems (Coltheart, 1980; Irwin & Yeomans, 1986). Visual persistence is thought to be a visible trace that is short lived following stimulus onset (~150 ms), reflects persistent activity in both the retina and early visual cortex (Duysens, Orban, Cremieux, & Maes, 1985), and contains only low-level stimulus properties. Alternatively, iconic memory is thought to last several hundred milliseconds following stimulus offset, contains higher-level information such as categorical coding (Merikle, 1980; Mewhort, Campbell, Marchetti, & Campbell, 1981) and spatiotopic coding (McRae, Butler, & Popiel, 1987), and involves higher-level visual areas (Keysers, Xiao, Földiák, & Perrett, 2005). Although it is not possible to know with certainty whether performance in the experiments reported here reflects one or both of these memory systems, the relatively long stimulus presentation (200 ms), high stimulus intensity, and bright display background have all been shown to lessen the contribution of visual persistence (Coltheart, 1980). These experiments could instead be designed to isolate visual persistence rather than iconic memory, and it seems possible that this store might gradually decay over time as neural firing rates return to baseline. However, studies of adaptation suggest that even such low-level “memories” might exhibit characteristics of all-or-none processing in some cases. For example, stabilizing images on the retina leads to adaptation, presumably in a gradual fashion as cells adapt more and more over time. However, when complex objects such as words are stabilized, elements of the images do not gradually disappear. Instead, discrete, coherent chunks such as entire letters vanish from awareness (Pritchard, 1961). Therefore, even when retinal neurons fade gradually, as in the case of adaptation, the percept that eventually reaches awareness can be all or none.

If a fading visual image can decay gradually in the retina but be perceived in an all-or-none fashion, is it possible that iconic memory is in fact decaying gradually but that our perception is immune to this decay until it passes some lower threshold? For example, Neisser (1967) notes, “Presumably the stored information decays gradually, and there is no precise moment when the icon ‘ends’. However, a time comes when it is no longer clear or detailed enough to be legible” (p. 23). For complex stimuli, I suspect that this sort of thresholding mechanism is possible. For example, Swagman, Province, and Rouder (2015) found that when words were briefly presented, either they were successfully identified or performance exhibited a complete failure as if the words had never been seen. Moreover, the probability of complete failure increased as word legibility was degraded by decreasing display duration. All-or-none word identification under perceptually degraded conditions is perhaps not surprising: Successful word identification requires that visual features be combined into a pattern, that pattern categorized as a letter, and that the letters combined to form a word. Consequently, even if iconic memory for a complex stimulus is fading gradually, the resulting identification performance may be unaffected until a catastrophic failure occurs in one or many downstream identification processes.

The critical question is whether a gradual decay of simple information, such as color or orientation, could produce the sudden-death identification performance observed here. For example, would lowering the contrast of a stimulus have no effect on orientation perception until it is so low that the orientation is completely imperceptible? Although some studies have suggested that orientation discrimination thresholds are largely invariant to stimulus contrast (e.g., Skottun, Bradley, Sclar, Ohzawa, & Freeman, 1987), more recent work suggests that orientation discrimination performance declines gradually as stimulus contrast is decreased (Mareschal & Shapley, 2004) or as external noise is added to the stimulus (Beaudot & Mullen, 2006). These results suggest that for simple visual features, gradually lessening the strength of the information produces a gradual decline in behavioral performance. Therefore, to the extent that manipulations of contrast and external noise are analogous to a gradually decaying iconic memory trace, a gradually decaying trace should produce a gradual decline in performance, not the all-or-none sudden death observed here.

Estimates of capacity decreased gradually as a function of retention interval. An enticing possibility is that this gradual decrease in capacity results from more and more items vanishing from memory over time. However, it is also possible that on any particular trial, all of the items in iconic memory vanish at the same moment rather than one at a time. Because capacity estimates are necessarily obtained by aggregating data over trials, if the time at which the items vanish from memory varies from trial to trial, it would nonetheless appear that capacity decreases gradually rather than abruptly. Such an abrupt and complete erasure of iconic memory is plausible. For example, it has been suggested that eye movements (Irwin, 1992) and eyeblinks (Thomas & Irwin, 2006) can wipe the contents of iconic memory. If the probability of making an eye movement or blink increases over time, then iconic memory is more likely to be erased completely at longer retention intervals, leaving only information that was transferred to working memory. Distinguishing between one item at a time and a complete erasure of iconic memory will require further experimentation, but doing so has the potential to greatly increase our understanding of iconic memory.

The sudden death of iconic memories is anticipated by discrete-capacity theories of working memory: If information vanishes entirely from iconic memory before it has had a chance to be transferred to working memory, then the information in working memory must necessarily inherit this complete information loss. It is not necessarily the case, however, that the discrete nature of iconic decay can completely explain the discrete-capacity limits in working memory. For example, even when stimuli are displayed indefinitely, working memory performance is limited to only a few items (Tsubomi, Fukuda, Watanabe, & Vogel, 2013). This result implies that visual working memory exhibits strict capacity limits independent of iconic memory. Nonetheless, the sudden death of iconic memory imposes strong constraints on what information is available to working memory, and furthering our understanding of the iconic store will be critical for understanding the subsequent processes that rely on it.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, PratteSupplementalMaterial for Iconic Memories Die a Sudden Death by Michael S. Pratte in Psychological Science

Acknowledgments

I thank Elizabeth Beene and Zach Buchanan for assisting with data collection.

Footnotes

Action Editor: Edward S. Awh served as action editor for this article.

Author Contributions: M. S. Pratte is the sole author of this article and is responsible for its content.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared that there were no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship or the publication of this article.

Funding: This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant No. R15MH113075.

Supplemental Material: Additional supporting information can be found at http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/suppl/10.1177/0956797617747118

Open Practices: Data and materials for these experiments have not been made publicly available. The design and analysis plans for the experiments were not preregistered.

References

- Adam K. C. S., Vogel E. K., Awh E. (2017). Clear evidence for item limits in visual working memory. Cognitive Psychology, 97, 79–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2017.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson R. C., Shiffrin R. M. (1968). Human memory: A proposed system and its control processes. Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 2, 89–195. doi: 10.1016/S0079-7421(08)60422-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Averbach E., Coriell A. S. (1961). Short-term memory in vision. Bell Labs Technical Journal, 40, 309–328. doi: 10.1002/j.1538-7305.1961.tb03987.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bae G., Allred S. R., Wilson C., Flombaum J. I. (2014). Stimulus-specific variability in color working memory with delayed estimation. Journal of Vision, 14(4), Article 7. doi: 10.1167/14.4.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bays P. M., Catalao R. F. G., Husain M. (2009). The precision of visual working memory is set by allocation of a shared resource. Journal of Vision, 9(10), Article 7. doi: 10.1167/9.10.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bays P. M., Husain M. (2008). Dynamic shifts of limited working memory resources in human vision. Science, 321, 851–854. doi: 10.1126/science.1158023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudot W. H. A., Mullen K. T. (2006). Orientation discrimination in human vision: Psychophysics and modeling. Vision Research, 46, 26–46. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2005.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley C., Pearson J. (2012). The sensory components of high-capacity iconic memory and visual working memory. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, Article 355. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappiello M., Zhang W. (2016). A dual-trace model for visual sensory memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 42, 1903–1922. doi:10.1037/xhp0000274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coltheart M. (1980). Iconic memory and visible persistence. Perception & Psychophysics, 27, 183–228. doi: 10.3758/BF03204258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan N. (2001). The magical number 4 in short-term memory: A reconsideration of storage capacity. Behavioral & Brain Sciences, 24, 87–114. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X01003922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donkin C., Nosofsky R., Gold J., Shiffrin R. (2015). Verbal labeling, gradual decay, and sudden death in visual short-term memory. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 22, 170–178. doi: 10.3758/s13423-014-0675-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donkin C., Nosofsky R. M., Gold J. M., Shiffrin R. M. (2013). Discrete-slots models of visual working-memory response times. Psychological Review, 120, 873–902. doi: 10.1037/a0034247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duysens J., Orban G. A., Cremieux J., Maes H. (1985). Visual cortical correlates of visible persistence. Vision Research, 25, 171–178. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(85)90110-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fougnie D., Suchow J. W., Alvarez G. A. (2012). Variability in the quality of visual working memory. Nature Communications, 3, 1229. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gegenfurtner K. R., Sperling G. (1993). Information transfer in iconic memory experiments. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 19, 845–866. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.19.4.845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin D. E. (1992). Memory for position and identity across eye movements. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 18, 307–317. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.18.2.307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin D. E., Yeomans J. M. (1986). Sensory registration and informational persistence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 12, 343–360. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.12.3.343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keysers C., Xiao D. K., Földiák P., Perrett D. I. (2005). Out of sight but not out of mind: The neurophysiology of iconic memory in the superior temporal sulcus. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 22, 316–332. doi: 10.1080/02643290442000103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftus G. R., Duncan J., Gehrig P. (1992). On the time course of perceptual information that results from a brief visual presentation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 18, 530–549. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.18.2.530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenc E. S., Pratte M. S., Angeloni C. F., Tong F. (2014). Expertise for upright faces improves the precision but not the capacity of visual working memory. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 76, 1975–1984. doi: 10.3758/s13414-014-0653-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luck S. J., Vogel E. K. (1997). The capacity of visual working memory for features and conjunctions. Nature, 390, 279–281. doi: 10.1038/36846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mareschal I., Shapley R. M. (2004). Effects of contrast and size on orientation discrimination. Vision Research, 44, 57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2003.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRae K., Butler B. E., Popiel S. J. (1987). Spatiotopic and retinotopic components of iconic memory. Psychological Research, 49, 221–227. doi: 10.1007/BF00309030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikle P. M. (1980). Selection from visual persistence by perceptual groups and category membership. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 109, 279–295. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.109.3.279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mewhort D. J. K., Campbell A., Marchetti F., Campbell J. I. (1981). Identification, localization, and “iconic memory”: An evaluation of the bar-probe task. Memory & Cognition, 9, 50–67. doi: 10.3758/BF03196951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neisser U. (1967). Cognitive psychology. New York, NY: Apple-Century-Crofts. [Google Scholar]

- Pratte M. S., Park Y. E., Rademaker R. L., Tong F. (2017). Accounting for stimulus-specific variation in precision reveals a discrete capacity limit in visual working memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 43, 6–17. doi: 10.1037/xhp0000302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard R. M. (1961). Stabilized images on the retina. Scientific American, 204, 72–79. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0661-72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouder J. N., Morey R. D., Cowan N., Zwilling C. E., Morey C. C., Pratte M. S. (2008). An assessment of fixed-capacity models of visual working memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 105, 5975–5979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711295105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skottun B. C., Bradley A., Sclar G., Ohzawa I., Freeman R. D. (1987). The effects of contrast on visual orientation and spatial frequency discrimination: A comparison of single cells and behavior. Journal of Neurophysiology, 57, 773–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling G. (1960). The information available in brief visual presentations. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 74(11), 1–29. doi: 10.1037/h0093759 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swagman A. R., Province J. M., Rouder J. N. (2015). Performance on perceptual word identification is mediated by discrete states. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 22, 265–273. doi: 10.3758/s13423-014-0670-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiele J. E., Pratte M. S., Rouder J. N. (2011). On perfect working-memory performance with large numbers of items. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 18, 958–963. doi: 10.3758/s13423-011-0108-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas L. E., Irwin D. E. (2006). Voluntary eyeblinks disrupt iconic memory. Perception & Psychophysics, 68, 475–488. doi: 10.3758/BF03193691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubomi H., Fukuda K., Watanabe K., Vogel E. K. (2013). Neural limits to representing objects still within view. The Journal of Neuroscience, 33, 8257–8263. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5348-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg R., Awh E., Ma W. J. (2014). Factorial comparison of working memory models. Psychological Review, 121, 124–149. doi: 10.1037/a0035234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg R., Shin H., Chou W.-C., George R., Ma W. J. J. (2012). Variability in encoding precision accounts for visual short-term memory limitations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 109, 8780–8785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117465109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilken P., Ma W. J. (2004). A detection theory account of change detection. Journal of Vision, 4(12), Article 11. doi: 10.1167/4.12.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Luck S. J. (2008). Discrete fixed-resolution representations in visual working memory. Nature, 453, 233–235. doi: 10.1038/Nature06860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Luck S. J. (2009). Sudden death and gradual decay in visual working memory. Psychological Science, 20, 423–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02322.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, PratteSupplementalMaterial for Iconic Memories Die a Sudden Death by Michael S. Pratte in Psychological Science