Abstract

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is a common complication after hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) and associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Preventing GVHD without chronic therapy or increasing relapse is a desired goal. Here we report a benchmark analysis to evaluate the performance of 6 GVHD prevention strategies tested at single institutions compared with a large multicenter outcomes database as a control. Each intervention was compared with the control for the incidence of acute and chronic GVHD and overall survival and against novel composite endpoints: acute and chronic GVHD, relapse-free survival (GRFS), and chronic GVHD, relapse-free survival (CRFS). Modeling GRFS and CRFS using the benchmark analysis further informed the design of 2 clinical trials testing GVHD prophylaxis interventions. This study demonstrates the potential benefit of using an outcomes database to select promising interventions for multicenter clinical trials and proposes novel composite endpoints for use in GVHD prevention trials.

Keywords: GVHD, Clinical trials, Hematopoietic cell, transplantation

INTRODUCTION

Immunologic complications of hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), such as graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), together with disease recurrence remain the largest challenges for improving outcomes. Chronic immunosuppressive therapy and in vivo or ex vivo graft manipulations may limit GVHD [1–4], but there is no existing GVHD prophylaxis strategy that completely eliminates the risk of acute or chronic GVHD. In addition, some approaches are more effective in preventing the acute and others in preventing the chronic form of the disease. Maximizing immunosuppression (IS) with multiple agents or stringent methods of graft manipulation through CD34+ cell selection and T cell depletion can reduce the rate of GVHD, but may increase the risk of disease relapse, graft failure, and infection [5,6]. Thus, a primary trial endpoint that includes only acute GVHD could misinterpret the true effect of a GVHD prophylaxis strategy on overall effectiveness of the transplantation. Accordingly, to better estimate the total effect of GVHD prophylaxis approaches on transplantation outcomes, the GVHD Committee of the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network (BMT CTN) [7] developed several composite GVHD endpoints that incorporate multiple outcomes.

Novel GVHD prophylaxis approaches generally start from single-institution studies and are later tested in multi-center clinical trials. Not only can results be misleading if based solely on the incidence of acute GVHD, but single-institution trials are also usually limited by small numbers of patients, highly selected populations, and differences in GVHD scoring methodology. Results might not be reproducible when applied to a larger, more heterogeneous patient group, and thus might not be reliable for developing large, expensive multicenter clinical trials. Using novel composite endpoints, the BMT CTN systematically assessed 6 GVHD prevention approaches tested in single trials and compared them with contemporary controls using standard GVHD prophylaxis, adjusting for differences in patient characteristics, to determine whether 1 or more demonstrated sufficient promise to warrant a multicenter trial.

Here we report this benchmark analysis as an approach to systematically select promising interventions tested in single centers for multicenter trials, and explore several outcomes to use as primary endpoints of HCT trials.

METHODS

Data Sources

The study includes data from 6 different single-center clinical trials using different GVHD prophylaxis regimens compared with contemporary controls from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR). The cohorts are as follows: (1) tacrolimus (Tac), methotrexate (MTX), and etanercept (etanercept) from the University of Michigan [8]; (2) Tac/MTX, pentostatin, and antithymocyte globulin (pentostatin/ATG) from the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center [9]; (3) post-transplantation cyclophosphamide (postCy) from Johns Hopkins University [10,11]; (4) CD34+ cell selection and T cell depletion (CD34 selection) from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center [1,12,13]; (5) Tac/MTX and bortezomib (bortezomib) from Dana Farber Cancer Institute [14]; and (6) Tac/MTX and maraviroc (maraviroc) from the University of Pennsylvania [15]. The contemporary control comprised patients who were reported to the CIBMTR and received Tac/MTX as the sole GVHD prophylaxis approach.

The CIBMTR is a research collaboration between the National Marrow Donor Program (NMDP)/Be The Match and the Medical College of Wisconsin. The CIBMTR represents an international network of transplantation centers that submit transplantation-related data for patients. It has been collecting HCT outcomes data for >40 years and has an extensive database of detailed patient-, transplantation-, and disease-related information with prospectively collected longitudinal data [16]. The trial data used in this analysis were part of institutional protocols approved by each center’s Institutional Review Board. The CIBMTR data were collected in compliance with HIPAA regulations and with all applicable federal regulations pertaining to the protection of human research participants, as determined by a continuous review by the NMDP’s Institutional Review Board and the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Eligibility

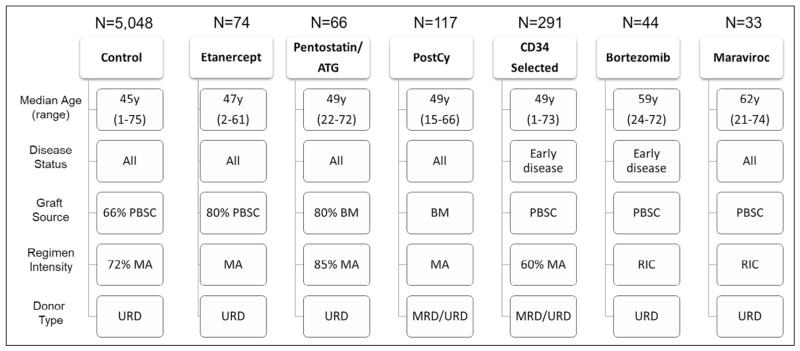

Figure 1 outlines the main demographic characteristics. In general, recipients who were included in the analysis underwent allogeneic HCT from an HLA-matched sibling donor or an HLA-matched or mismatched unrelated donor (URD) for treatment of hematologic malignancies between 2000 and 2011. Each cohort from the single-center experiences had specific eligibility criteria; therefore, there were differences among the cohorts in age, disease states, and transplantation techniques.

Figure 1.

Demographic outline of all the GVHD prophylaxis cohorts. This figure outlines the main differences between the cohorts analyzed. For the boxes related to transplantation characteristics without percentages, all populations used that particular approach. BM indicates bone marrow; MA, myeloablative conditioning; MRD, matched related donor; RIC, reduced-intensity conditioning.

Outcomes

The incidences of acute (grade II–IV and III–IV) GVHD and chronic GVHD were defined as the development and severity of these complications, as graded by the treating physician. Organ stage was collected for control and all clinical trials, and grades were assigned according to revised criteria for acute GVHD [17]. Events for disease-free survival (DFS) were defined as death, disease relapse, or disease progression, whichever occurred first. The event for overall survival (OS) was defined as death from any cause.

An important objective of this analysis was to explore novel, clinically meaningful outcome measurements in HCT trials. Interventions used to prevent GVHD have the potential to influence other important outcomes after HCT, including disease relapse, infections, and mortality. Thus composite endpoints that incorporate multiple outcomes of clinical relevance were explored. Off-IS relapse-free survival (ISRS), which included withdrawal of all IS or other systemic intervention (eg, extracorporeal photopheresis) for treatment or prophylaxis of GVHD (except for adrenal replacement doses of corticosteroids), and without primary disease progression or death. Because the date of IS discontinuation was not reliably available in the control group and the practices of IS use and withdrawal vary across centers, this information was obtained for each cohort with the caveat that this was not mandated by a specific protocol and thus represented nonstandardized center practices. Chronic GVHD relapse-free survival (CRFS) included survival without development of chronic GVHD plus disease relapse or progression or death. GVHD-relapse-free survival (GRFS) included survival without acute grade III–IV GVHD plus chronic GVHD plus disease relapse or progression or death.

Statistical Analysis

Cumulative incidence function was used to calculate GVHD and treatment-related mortality outcomes to account for competing risks. The Kaplan-Meier estimator was used to calculate OS, DFS, GRFS, and CRFS. IRFS was analyzed only descriptively in each cohort using frequencies. There were distinct differences among the cohorts in terms of age, disease and disease status, graft source, donor type, and conditioning regimen intensity. Multivariate Cox models were constructed for each outcome (acute GVHD grade II–IV, acute GVHD grade III–IV, chronic GVHD, and OS), adjusting for variables that were significantly (P < .05) associated with outcomes. Variables considered in the regression models included age, sex, performance score (80% to 100%, <80%, or missing); disease status (for leukemia and myelodysplasia [MDS]: early, first complete remission or early MDS without excess of blasts in the bone marrow [<5%]; intermediate, second or greater complete remission; advanced, active disease or MDS with excess blasts in the bone marrow; for lymphoma: chemotherapy-sensitive and chemotherapy-resistant); donor type (matched related, matched URD, and mismatched URD); and graft source (bone marrow or peripheral blood stem cells [PBSCs]). Each of the 6 cohorts and the control group were included in the analysis. In addition, adjusted cumulative incidence curves and adjusted survival probabilities were estimated using the stratified Fine and Gray model and the stratified Cox model, respectively. Comparisons were done between each cohort and the control cohort plus all of the other cohorts. For each comparison, the cohort of interest was adjusted to the control population, which included the control cohort plus the other 5 cohorts. Adjusted probabilities represent what would have occurred had the treatment used at a particular center been applied to the common population of patients in the combined cohort.

To further explore novel composite outcomes, we performed a series of analyses on the CIBMTR controls. The inclusion of disease relapse or progression in a composite outcome requires some knowledge of the diseases and disease statuses included in the eligibility criteria. Thus, a separate analysis was performed to assess the differential impact of different disease on GRFS. We also assessed the impact of acute GVHD grade on overall mortality, disease relapse, and development of chronic GVHD using a Cox regression model including acute GVHD grade as a time-dependent covariate to determine which grades of acute GVHD were associated with certain longer-term outcomes and so would be important to include in a composite endpoint such as GRFS. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Population

Figure 1 outlines the major characteristics of the cohorts. The Tac/MTX control cohort comprised 5048 patients from 138 transplantation centers. The most common diagnosis was acute myelogenous leukemia in all cohorts except the bortezomib cohort, in which non-Hodgkin lymphoma was the most common diagnosis. The CD34 selection cohort contained mostly patients with early disease at time of transplantation, whereas the pentostatin/ATG cohort contained mostly patients with advanced disease. URD was the most common donor type in all cohorts; most patients in the bortezomib cohort underwent transplantation with an HLA-mismatched URD graft. Mobilized PBSCs were used more frequently in all cohorts except for the postCy and pentostatin/ATG cohorts. Myeloablative conditioning was the predominant regimen in all cohorts except the bortezomib and maraviroc cohorts, which included mostly reduced-intensity conditioning regimens. The median duration of follow-up for survivors was ≥40 months for all cohorts except the CD34 selection and maraviroc cohorts, which had a median follow-up of 24 and 12 months, respectively.

Univariate Outcomes

Table 1 outlines the univariate outcomes for all cohorts. The cumulative incidence of grade II–IV and grade III–IV acute GVHD at day +100 after transplantation ranged from 10% to 58% and from 3% to 25%, respectively. The cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD at 1 year post-transplantation ranged from 8% to 65%. DFS and OS at 1 year after transplantation ranged from 40% to 67% and from 59% to 76%, respectively. Heterogeneity of risk factors among the cohorts required multivariate adjustments for fair comparisons.

Table 1.

Univariate Analysis of GVHD and Survival Across the Study Cohorts According to GVHD Prophylaxis Approach

| Outcome | Cohort | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Control (Tac/MTX) | Etanercept | Pentostatin/ATG | PostCy | CD34 Selection | Bortezomib | Maraviroc | |

| Acute GVHD grade II–IV | |||||||

| Number | 5031 | 72 | 62 | 117 | 281 | 42 | 31 |

| Incidence at 100 days, % (95% CI) | 45 (44–46) | 58 (47–69) | 48 (36–61) | 54 (44–63) | 10 (6–13) | 26 (14–40) | 16 (6–31) |

| Acute GVHD grade III–IV | |||||||

| Number | 5036 | 72 | 62 | 116 | 281 | 43 | 31 |

| Incidence at 100 days, % (95% CI) | 24 (22–25) | 25 (16–36) | 15 (7–24) | 17 (10–24) | 4 (2–7) | 12 (4–23) | 3 (0–12) |

| Chronic GVHD | |||||||

| Number | 4870 | 71 | 64 | 117 | 272 | 43 | 32 |

| Incidence at 1 year, % (95% CI) | 45 (43–46) | 65 (53–75) | 36 (25–49) | 16 (8–25) | 8 (5–11) | 40 (26–54) | 18 (6–35) |

| DFS | |||||||

| Number | 4780 | 71 | 64 | 115 | 290 | 41 | 32 |

| Incidence at 1 year, % (95% CI) | 52 (51–54) | 58 (46–69) | 56 (43–68) | 47 (38–56) | 67 (61–73) | 63 (48–77) | 40 (24–58) |

| OS | |||||||

| Number | 5048 | 74 | 64 | 116 | 291 | 43 | 32 |

| Incidence at 1 year, % (95% CI) | 60 (59–61) | 64 (52–74) | 57 (45–69) | 59 (50–67) | 76 (70–81) | 74 (60–86) | 59 (42–75) |

Adjusted Comparisons

Table 2 outlines the adjusted probabilities of each outcome and the multivariate comparison of each cohort and the control. CD34 selection (P < .001) and bortezomib (P = .042) were associated with lower rates of grade II–IV acute GVHD. CD34 selection (P < .001) and pentostatin/ATG (P = .037) were associated with lower rates of grade III–IV acute GVHD. PostCy (P < .001), CD34 selection (P < .001), pentostatin/ATG (P = .013), and maraviroc (P < .001) were associated with lower rates of chronic GVHD. Pentostatin/ATG (P = .031), CD34 selection (P < .001), and bortezomib (P = .006) were associated with lower mortality.

Table 2.

Multivariate Analysis and Adjusted Probabilities of GVHD and Survival Across Cohorts and Compared with Controls

| Outcome | Control (Tac/MTX) | Etanercept | Pentostatin/ATG | PostCy | CD34 Selection | Bortezomib | Maraviroc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade II–IV aGVHD, % (95% CI) | 45 (43–46) | 50 (40–60) | 44 (33–55) | 57 (48–66) | 10 (7–14) | 27 (15–40) | 23 (9–41) |

| HR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.04 (.78–1.41) | .91 (.64–1.3) | 1.24 (.94–1.62) | .24* (.17–0.32) | .58* (.35–0.98) | 1.08 (.63–1.85) |

| Grade III–IV aGVHD, % (95% CI) | 23 (22–24) | 21 (14–31) | 14 (7–23) | 21 (13–30) | 4 (2–8) | 10 (4–20) | 4 (0–18) |

| HR (95% CI) | 1.00 | .86 (.55–1.34) | .50* (.26–0.96) | .90 (.58–1.4) | .31* (.2–0.47) | .48 (.22–1.01) | .91 (.4–2.05) |

| cGVHD, % (95% CI) | 45 (43–46) | 59 (47–69) | 39 (27–51) | 13 (7–20) | 8 (5–11) | 43 (28–58) | 19 (7–35) |

| HR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.50* (1.12–2) | .60* (.4–0.9) | .24* (.14–0.41) | .10* (.07–0.15) | .73 (.49–1.1) | .29* (.12–0.69) |

| OS, % (95% CI) | 60 (58–61) | 66 (55–75) | 63 (52–73) | 57 (47–66) | 73 (67–78) | 79 (66–88) | 64 (47–77) |

| HR† (95% CI) | 1.00 | .85 (.63–1.16) | .69* (.5–0.97) | 1.07 (.82–1.4) | .68* (.55–0.83) | .53* (.34–0.83) | .80 (.46–1.4) |

| DFS, % (95% CI) | 52 (51–53) | 58 (46–68) | 61 (49–71) | 46 (37–55) | 65 (59–71) | 67 (51–78) | 46 (29–61) |

| HR‡ (95% CI) | 1.00 | .92 (.68–1.25) | .65* (.47–0.91) | 1.21 (.94–1.56) | .66* (.55–0.81) | .67 (.44–1.02) | 1.20 (.76–1.91) |

The probabilities in the first row of each outcome represent estimates at different time points: acute GVHD of 100 days, chronic GVHD and survival outcomes at 12 months.

aGVHD indicates acute graft-versus-host disease; cGVHD, chronic graft-versus-host disease; HR, hazard ratio.

Represents comparisons with the control that are significantly different (P < .05).

The model is for overall mortality.

The model is for treatment failure (1-DFS).

IRFS

The proportion of patients in each cohort who discontinued (or who never received) IS for GVHD and were without primary disease relapse or progression at 12 months post-transplantation was as follows: maraviroc, 25%; etanercept, 7%; pentostatin/ATG, 14%; bortezomib, 16%; PostCy, 32%; CD34 selection, 41%. These estimates were not available in the control cohort, and they were influenced by center practices for tapering IS. The concern was that even though important clinically, IRFS could not be reliably used as a primary endpoint owing to a lack of a standardized IS tapering approaches across centers and a dearth of reliable baseline estimates of expected IRFS rates. Prospective trials with clear capture of IS use during the first transplantation could further demonstrate the expected proportion of patients who are off IS at the end of this period.

CRFS

The next step was to identify an alternative to IRFS, which included freedom from the development of chronic GVHD before 12 months after transplantation as the event, along with freedom from either disease relapse/progression or death. Assumptions include that acute GVHD would have resolved, resulted in death, or evolved to chronic GVHD by 12 months. Another assumption is if the patient developed chronic GVHD any time before 12 months, this complication was either still present or the patient was still receiving IS or other systemic treatment for GVHD at 12 months. The CRFS rates at 12 months were as follows Tac/MTX control, 22% (95% confidence interval [CI], 21% to 23%); etanercept, 9% (95% CI, 4% to 17%); maraviroc, 25% (95% CI, 11% to 41%); postCY, 33% (95% CI, 25% to 42%); pentostatin/ATG, 34% (95% CI, 23% to 46%); bortezomib, 39% (95% CI, 25% to 53%); and CD34 selection, 59% (95% CI, 53% to 65%).

GRFS

The benchmark analysis using Tac/MTX as the control clearly demonstrated that some interventions were better at controlling acute GVHD than controlling chronic GVHD. In the Tac/MTX control group, 85% of patients who developed grade III–IV acute GVHD subsequently developed chronic GVHD, relapsed, or died by 12 months, and 56% either died or relapsed. Using acute GVHD grade as a time-dependent covariate for disease relapse/progression or death along with all the CRFS components confirmed the prognostic impact of grade III–IV acute GVHD. The development of grade III and grade IV acute GVHD was associated with a relative risk (RR) of treatment failure (death or relapse/progression [1-DFS]) of 1.34 (95% CI, 1.17 to 1.52; P < .001) and 3.39 (95% CI, 2.88 to 3.99; P < .001), respectively. The corresponding RRs for the development of CRFS were 1.53 (95% CI, 1.38 to 1.69; P < .001) and 2.96 (95% CI, 2.56 to 3.42; P < .001) (Table 3). Conversely, the development of grade II acute GVHD was not predictive of treatment failure (death or progression; P = .779), which reinforced the selection of grade III–IV for these composite outcomes.

Table 3.

Impact of Maximum Grade of Acute GVHD on Death or Relapse/Progression (Treatment Failure) or on the Development of CRFS

| Acute GVHD Maximum Grade | n | RR | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment failure | ||||

| 0–I | 1815 | 1 | — | — |

| II | 863 | 1.02 | .9–1.15 | .779 |

| III | 609 | 1.34 | 1.17–1.52 | <.001 |

| IV | 246 | 3.39 | 2.88–3.99 | <.001 |

| CRFS | ||||

| 0–I | 1815 | 1 | ||

| II | 863 | 1.24 | 1.13–1.36 | <.001 |

| III | 609 | 1.53 | 1.38–1.69 | <.001 |

| IV | 246 | 2.96 | 2.56–3.42 | <.001 |

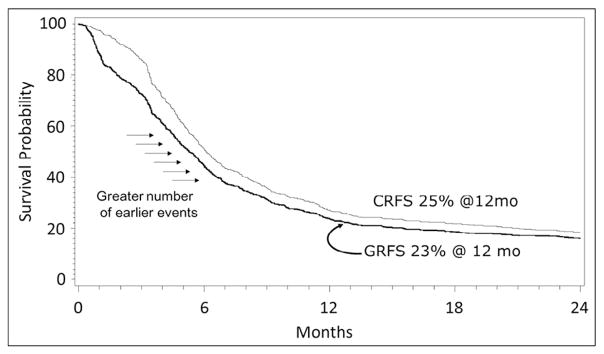

Figure 2 illustrates the differences between GRFS and CRFS in a subset of Tac/MTX recipients from the control population. The figure shows a higher number of events early after transplantation for the GRFS outcome, due to the occurrence of grade III–IV acute GVHD. However, the 12-month probabilities were similar (GRFS, 23%; CRFS, 25%). Thus, at least in the Tac/MTX cohort, most patients who developed grade III–IV acute GVHD will develop chronic GVHD.

Figure 2.

CRFS versus GRFS assessment among recipients of tacrolimus and methotrexate with patients with early or intermediate risk disease.

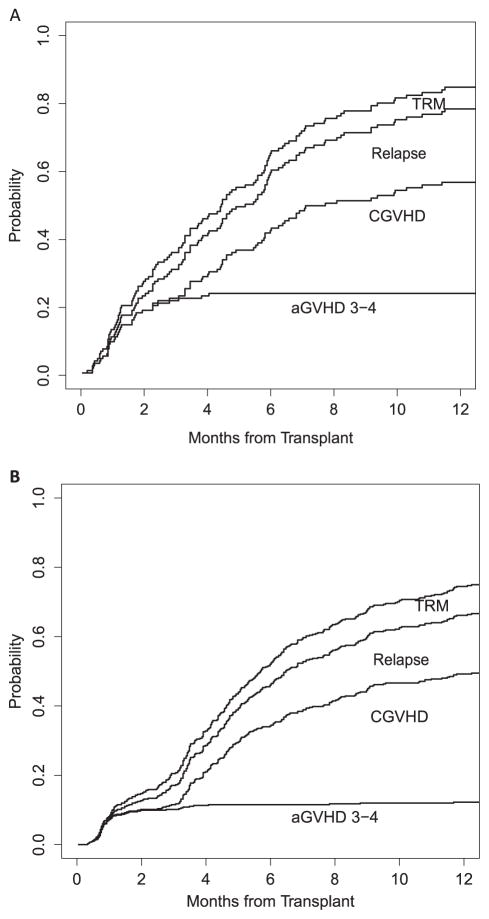

Each component of these composite endpoints needs to be considered according to the patient population being studied. Most GVHD prophylaxis trials have broad selection criteria, including patients with a wide range of diseases, disease states, and other characteristics. GRFS at 12 months has been estimated in different diseases. For MDS and chronic lymphocytic leukemia, the hazard ratios for GRFS were 1.55 (95% CI, 1.18 to 2.04; P < .001) and 1.42 (95% CI, 1.11 to 1.82; P < .001), respectively, compared with acute leukemia. Figure 3 outlines the stacked plot of each GRFS outcome by different disease groups, showing that the incidence of acute GVHD in patients with MDS and chronic lymphocytic leukemia was the most important component responsible for the differences in GRFS.

Figure 3.

Stacked plots with all components of GRFS in patients with MDS and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (A) and in patients with acute leukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (B).

DISCUSSION

The objective of this study was to identify promising interventions for GVHD prevention from single-center experiences for study in a multicenter setting. This benchmark analysis used novel composite endpoints and adjusted for patient differences between each cohort and the control group to minimize the center effect and provide a general comparison with anticipated outcomes in a normalized population. The result of these analyses led to the development of 2 multicenter clinical trials with novel composite endpoints: PROGRESS 1 and 2 (Prevention and Reduction of GVHD and Relapse, Enhancing Survival after Stem Cell Transplant). These trials were developed to address GVHD prevention after reduced-intensity conditioning and myeloablative conditioning. PROGRESS 1 (BMT CTN 1203; NCT02208037) is a randomized phase II, 3-arm trial testing bortezomib, maraviroc, and postCy in reduced-intensity conditioning transplantation. The primary endpoint for this trial is GRFS. Results of this trial will be compared with a contemporary control using prospective data collected by the CIBMTR from centers not participating in the clinical trial. This nonrandomized contemporary control will aid in selection of the most promising intervention to be studied in a phase III setting. PROGRESS 2 (BMT CTN 1301; NCT02345850) is a phase III randomized, open-label, 3-arm trial comparing CD34 selection versus postCy versus a control of Tac/MTX. The primary endpoint selected was CRFS, which was compared between each intervention arm and its control arm. CRFS was selected mainly to focus on chronic GVHD prevention, given that both of these calcineurin inhibitor-free-based prophylaxis regimens demonstrated their most profound effect on the development of chronic GVHD. Using CRFS in this setting would increase the precision of the analysis of this outcome, along with relapse and survival.

This benchmark analyses paired data with a contemporaneous multicenter Tac/MTX control. Most interventions performed very close to the control for most outcomes. CD34 selection had the most significant differences compared with control, with less grade III–IV acute GVHD, less chronic GVHD, and longer DFS and OS. However, most patients in the CD34 selection cohort had early disease, and when the analysis was restricted to patients with intermediate and advanced disease, survival was similar to that of controls (data not shown). PostCy is a relatively novel and potent approach to GVHD prevention that is able to break the HLA barrier by allowing safe engraftment of mismatched grafts without excess GVHD [18]. PostCy is a common approach in haploidentical donor HCT, and GVHD rates are comparable to those of other HCT approaches with matched donors [11,19–23]. In this analysis, with the majority of transplants from HLA-matched donors [10], postCy was associated with less chronic GVHD, but no change in DFS or OS. CD34 selection and postCy, when used in the setting of myeloablative conditioning with HLA-matched donors, do not require long-term use of chronic IS, which is a potential advantage. Pentostatin/ATG also demonstrated promising effects, especially in chronic GVHD and other outcomes, and it clearly can be included as an intervention to be studied. However, 2 other trials assessing the effect of ATG have been ongoing in North America, which has dampened the enthusiasm for specifically testing this intervention further in the BMT CTN trials. Other interventions, including bortezomib and maraviroc, were mostly associated with improved control of acute GVHD. Etanercept performed in line with the control, with no significant improvement in any of the outcomes and possibly worse rates of chronic GVHD. This could be explained by differential adjudication of chronic GVHD between a single center versus what is reported to the CIBMTR.

Single-center phase II results are often not reproduced in multicenter phase III studies. Martin et al. [24] evaluated the probability of success of several GVHD treatments and demonstrated that several were advanced to phase III using preliminary data that were insufficiently analyzed, or that the results were not clearly superior to expected success rates of GVHD treatment. The data from our benchmark analysis led to the conclusion that etanercept is not sufficiently promising to warrant further evaluation.

The search for a new composite endpoint in testing GVHD prevention intervention is of great interest, given that several competing events can be influenced by a specific approach. The BMT CTN performed a secondary analysis of 2 clinical trials to compare results of a single-arm phase II trial. The comparison was between CD34 selection and calcineurin inhibitor-based GVHD prevention [25]. All outcomes were comparable, except for a significantly lower incidence of chronic GVHD with CD34 selection. When the composite endpoint CRFS was tested, a benefit for CD34 selection was seen.

These composite outcomes seek an ideal state that defines a successful transplantation—that is, alive without cancer and not requiring IS for treatment or prevention of GVHD—thus making it attractive for use in clinical trials. However, because these composite endpoints include disease relapse, it is important to assess the population and its diseases before comparing overall GRFS rates across studies. Several known factors influence each component included in GRFS and CRFS. Patient age, performance status, comorbidities, donor sex, disease, disease status at transplantation, conditioning type and intensity, graft source, donor type, and HLA matching can differentially influence each component of these endpoints, even when a composite endpoint such as GRFS or CRFS is used in a clinical trial. It is important to also examine each of the individual components to see which component might be driving differences in outcomes, as shown in Figure 3. The Minnesota group further analyzed GRFS in diverse populations and demonstrated a significant variation between children and adults and among cord blood, PBSCs, and bone marrow grafts [26]. Similarly, Solh et al. [27] analyzed predictors for GRFS. In addition to graft source and donor type, that group identified an association between the Disease Risk Index and GRFS. It is important to stress that composite endpoints can also vary considerably based on patient selection, disease, and disease status. These composite endpoints also improved efficiency and reduced sample sizes by accumulating a number of important criteria that need to be met to define success. Nevertheless, in the present analysis, with a large cohort of more than 5000 patients, fewer than 25% were without an event in the CRFS composite endpoint—that is, alive, disease-free, and without chronic GVHD by 12 months. Despite some variations, these composite outcomes are likely to provide a good approximation of current expectations using standard transplantation methods, and they serve as a benchmark for further improvements needed in the field of transplantation.

Acknowledgments

Financial disclosure: Support for this study was provided by Grant #U10HL069294 to the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Cancer Institute, along with contributions by Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (BMT CTN 1203) and Miltenyi Biotec (BMT CTN 1301). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the above-mentioned parties. The CIBMTR is supported primarily by Grant U24-CA76518 from the National Cancer Institute; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and Grant HHSH234200637015C from the Health Resources and Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services.

Conflict of interest statement: There are no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Devine SM, Carter S, Soiffer RJ, et al. Low risk of chronic graft-versus-host disease and relapse associated with T cell-depleted peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia in first remission: results of the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network Protocol 0303. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:1343–1351. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nash RA, Antin JH, Karanes C, et al. Phase 3 study comparing methotrexate and tacrolimus with methotrexate and cyclosporine for prophylaxis of acute graft-versus-host disease after marrow transplantation from unrelated donors. Blood. 2000;96:2062–2068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ratanatharathorn V, Nash RA, Przepiorka D, et al. Phase III study comparing methotrexate and tacrolimus (prograf, FK506) with methotrexate and cyclosporine for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis after HLA-identical sibling bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1998;92:2303–2314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Storb R, Deeg HJ, Whitehead J, et al. Methotrexate and cyclosporine compared with cyclosporine alone for prophylaxis of acute graft versus host disease after marrow transplantation for leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:729–735. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198603203141201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bacigalupo A, Van Lint MT, Occhini D, et al. Increased risk of leukemia relapse with high-dose cyclosporine A after allogeneic marrow transplantation for acute leukemia. Blood. 1991;77:1423–1428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagner JE, Thompson JS, Carter SL, Kernan NA. Effect of graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis on 3-year disease-free survival in recipients of unrelated donor bone marrow (T-Cell Depletion Trial): a multi-centre, randomised phase II–III trial. Lancet. 2005;366:733–741. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66996-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weisdorf D, Carter S, Confer D, Ferrara J, Horowitz M. Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network (BMT CTN): addressing unanswered questions. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:257–262. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.11.017. discussion 255–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi SW, Stiff P, Cooke K, et al. TNF-inhibition with etanercept for graft-versus-host disease prevention in high-risk HCT: lower TNFR1 levels correlate with better outcomes. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:1525–1532. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parmar S, Andersson BS, Couriel D, et al. Prophylaxis of graft-versus-host disease in unrelated donor transplantation with pentostatin, tacrolimus, and mini-methotrexate: a phase I/II controlled, adaptively randomized study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:294–302. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.6357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luznik L, Bolaños-Meade J, Zahurak M, et al. High-dose cyclophosphamide as single-agent, short-course prophylaxis of graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2010;115:3224–3230. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-251595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luznik L, O’Donnell PV, Symons HJ, et al. HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation for hematologic malignancies using nonmyeloablative conditioning and high-dose, posttransplantation cyclophosphamide. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:641–650. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jakubowski AA, Small TN, Kernan NA, et al. T-cell depleted unrelated donor stem cell transplantation provides favorable disease-free survival for adults with hematologic malignancies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:1335–1342. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jakubowski AA, Small TN, Young JW, et al. T cell-depleted stem-cell transplantation for adults with hematologic malignancies: sustained engraftment of HLA-matched related donor grafts without the use of antithymocyte globulin. Blood. 2007;110:4552–4559. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-093880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koreth J, Stevenson KE, Kim HT, et al. Bortezomib-based graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis in HLA-mismatched unrelated donor transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3202–3208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.0984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reshef R, Luger SM, Hexner EO, et al. Blockade of lymphocyte chemotaxis in visceral graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:135–145. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1201248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pasquini M, Wang Z, Horowitz MM, Gale RP. 2013 report from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR): current uses and outcomes of hematopoietic cell transplants for blood and bone marrow disorders. Clin Transpl. 2013:187–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, et al. 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15:825–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luznik L, Jalla S, Engstrom LW, Iannone R, Fuchs EJ. Durable engraftment of major histocompatibility complex-incompatible cells after nonmyeloablative conditioning with fludarabine, low-dose total body irradiation, and posttransplantation cyclophosphamide. Blood. 2001;98:3456–3464. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.12.3456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bashey A, Zhang X, Sizemore CA, et al. T-cell-replete HLA-haploidentical hematopoietic transplantation for hematologic malignancies using post-transplantation cyclophosphamide results in outcomes equivalent to those of contemporaneous HLA-matched related and unrelated donor transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1310–1316. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.3523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brunstein CG, Fuchs EJ, Carter SL, et al. Alternative donor transplantation after reduced intensity conditioning: results of parallel phase 2 trials using partially HLA-mismatched related bone marrow or unrelated double umbilical cord blood grafts. Blood. 2011;118:282–288. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-344853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ciurea SO, Zhang MJ, Bacigalupo AA, et al. Haploidentical transplant with posttransplant cyclophosphamide vs matched unrelated donor transplant for acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2015;126:1033–1040. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-04-639831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanate AS, Mussetti A, Kharfan-Dabaja MA, et al. Reduced-intensity transplantation for lymphomas using haploidentical related donors vs HLA-matched unrelated donors. Blood. 2016;127:938–947. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-09-671834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kasamon YL, Luznik L, Leffell MS, et al. Nonmyeloablative HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation with high-dose posttransplantation cyclophosphamide: effect of HLA disparity on outcome. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:482–489. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin PJ, Inamoto Y, Carpenter PA, Lee SJ, Flowers ME. Treatment of chronic graft-versus-host disease: past, present and future. Korean J Hematol. 2011;46:153–163. doi: 10.5045/kjh.2011.46.3.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pasquini MC, Devine S, Mendizabal A, et al. Comparative outcomes of donor graft CD34+ selection and immune suppressive therapy as graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis for patients with acute myeloid leukemia in complete remission undergoing HLA-matched sibling allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3194–3201. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.7071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holtan SG, DeFor TE, Lazaryan A, et al. Composite end point of graft-versus-host disease-free, relapse-free survival after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2015;125:1333–1338. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-10-609032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Solh M, Zhang X, Connor K, et al. Factors predicting graft-versus-host disease-free, relapse-free survival after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: multivariable analysis from a single center. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22:1403–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]