Abstract

Background

Nasal and sinus symptoms (NSS) are common to many health conditions, including chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS). Few studies have investigated the occurrence and severity of, and risk factors for, acute exacerbations of NSS (AENSS) by CRS status (current, past, or never met European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis [EPOS] criteria for CRS).

Methods

Four seasonal questionnaires were mailed to a stratified random sample of Geisinger primary care patients. Logistic regression was used to identify individual characteristics associated with AENSS occurrence and severity by CRS status (current long-term, current recent, past, never) using EPOS subjective symptoms-only (EPOSS) CRS criteria. We operationalized three AENSS definitions based on prescribed antibiotics or oral corticosteroids, symptoms, and symptoms with purulence.

Results

Baseline and at least one follow-up questionnaires were available from 4,736 subjects. Self-reported NSS severity with exacerbation was worst in the current long-term CRS group. AENSS was common in all subgroups examined and generally more common among those with current EPOSS CRS. Seasonal prevalence of AENSS differed by AENSS definition and CRS status. Associations of risk factors with AENSS differed by definition, but CRS status, body mass index, asthma, hay fever, sinus surgery history, and winter season consistently predicted AENSS.

Conclusions

In this first longitudinal, population-based study of three AENSS definitions, NSS and AENSS were both common, sometimes severe, and differed by EPOSS CRS status. Contrasting associations of risk factors for AENSS by the different definitions suggest a need for a standardized approach to definition of AENSS.

Keywords: chronic rhinosinusitis, epidemiology, exacerbation, longitudinal

Introduction

There are few prior longitudinal studies of nasal and sinus symptoms (NSS) and their acute exacerbation (AENSS) in general population samples and no standardized approaches to measurement of AENSS in epidemiologic studies. NSS are common to multiple health conditions, can be relapsing and remitting, can become chronic as in the case of chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS), and have a significant individual and population impact (1–8). The European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps (EPOS) has operationalized a clinical definition of CRS, requiring both subjective symptoms which must be present for 12 continuous weeks and objective confirmation of sinonasal mucosal inflammation (e.g. via sinus computed tomography [CT]). For epidemiologic studies, EPOS only requires the presence of subjective symptoms (we designate as EPOSS) (1, 2).

Difficulties in obtaining objective evidence of inflammation have been an impediment to large-scale, population-based epidemiologic studies. Depending on individual characteristics, onset, duration, and season, the sudden onset or worsening of NSS could be an indication for allergic rhinitis (AR), acute rhinosinusitis (ARS), an acute exacerbation of chronic rhinosinusitis (AECRS), or other related diagnoses. Published studies of exacerbation among CRS patients have primarily focused on bacteriology (9–11), immunology (12, 13), and medical treatments (14–17), as opposed to population-based occurrence, severity, risk factors, and natural history. The International Consensus Statement on Allergy and Rhinology (ICAR), therefore, has declared a need for prevalence estimates of AECRS and more prospective studies, especially those which compare several definitions of AECRS (2).

As such, the objectives of this study were to evaluate and compare seasonal prevalence of AENSS by EPOSS CRS status (hereafter CRS status) across three definitions of AENSS; describe NSS severity by CRS and AENSS status; and identify self-reported individual characteristics associated with AENSS by CRS status. We addressed these objectives in a population-based longitudinal study using a sample of primary care patients from Geisinger who are representative of the general population in the area of central and northeastern Pennsylvania.

Materials and Methods

Study overview

Details of the study design have been published elsewhere (5, 18). Briefly, in 2014, adult (at least 18 years of age) primary care patients were selected from the EHR of Geisinger to participate in a study of the epidemiology of CRS. Individuals who responded to the baseline questionnaire were additionally mailed four seasonal follow-up questionnaires over the course of 16-months, to evaluate seasonal exacerbations (Table 1; for example questionnaire see online supplemental material S1). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Geisinger, which has an IRB Authorization Agreement with the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act authorization and written informed consent waivers were approved by the IRB.

Table 1.

Description of longitudinal questionnaires and number of responders

| Description | April 2014 | October 2014 | February 2015 | May 2015 | August 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Questionnaire | Baseline | Fall Exacerbation | Winter Exacerbation | Spring Exacerbation | Summer Exacerbation |

| Mailings | 3 (to August 2014) | 2 (to January 2015) | 1 | 1 | 2 (to December 2015) |

| Items | 94 | 87 | 15 | 15 | 79 |

| Sections | AENSS exacerbation | AENSS exacerbation | AENSS exacerbation | AENSS exacerbation | |

| CRS treatment (4wk) | CRS treatment (4wk) | CRS treatment (4wk) | CRS treatment (4wk) | ||

| Current CRS | Current CRS | Current CRS | |||

| Secondary CRS | Secondary CRS* | Secondary CRS | |||

| Minor symptoms | Minor symptoms | Minor symptoms | |||

| Doctor diagnoses | Anxiety | Work exposures and impacts | |||

| Socioeconomic status | Depression symptoms | SHS and farm contacts | |||

| Responders | 7847 | 4966 | 5094 | 4089 | 4600 |

Abbreviations: CRS = chronic rhinosinusitis; SES = socioeconomic status; SHS = second-hand smoke

Secondary CRS indicates more specific questions about NSS frequency and severity not included as part of the diagnostic criteria for CRS

Study population

Geisinger provides primary care services to over 450,000 patients, with the majority residing in central and northeastern Pennsylvania. The source population for this study consisted of 200,769 adult primary care patients who had available EHR data, including race/ethnicity. Stratified sampling was utilized to over represent individuals more likely to have CRS, as well as racial/ethnic minorities (8% of Geisinger patients identify as non-white race/ethnicity). From the source population, 23,700 individuals were selected to participate in the baseline survey and baseline responders (n = 7,847) were mailed four follow-up questionnaires with four-month intervals in-between (Table 1).

Description of sampling method

The sampling method has been reported previously (5, 18). Briefly, individuals with a greater likelihood of having CRS were over-sampled by using EHR data to categorize individuals into three groups, based on International Classification of Disease (ICD)-9 codes as well as Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes from patient medical records for: CRS, asthma, allergic rhinitis, sinus procedures, and related information (18). Oversampling of racial and ethnic minorities was also performed. Sampling proportions are reported elsewhere (5).

CRS classification

Individuals were classified as having EPOSS CRS as previously reported (5, 18). In brief, CRS status was determined using subject responses concerning the frequency of the cardinal symptoms of CRS (nasal congestion/blockage, green/yellow nasal discharge [purulence], post-nasal drip, smell loss, facial pain, and facial pressure), as defined by EPOS (1). Based on responses to these questions at the baseline and first follow-up questionnaires, subjects were classified as “current long-term” (current CRS at both questionnaires), “current recent” (past or never CRS at baseline, current CRS at follow-up), “past” (past CRS at baseline, not current at follow-up) or “never” (no CRS at either questionnaire). Only these questionnaires were used for determining CRS status in this study because two of the follow-up questionnaires (winter and spring exacerbation) did not include questions about EPOS symptoms over the past three months and we did not want to induce reverse causality in the association of CRS status and exacerbation. We did not differentiate between CRS with and without nasal polyps since objective evidence of CRS was unavailable for all study participants and therefore no way to reliably phenotype these subjects.

Operationalization of NSS severity and AENSS

NSS severity was assessed in two different ways. The first used self-reported rating of NSS on a 10-point visual analog scale while the second used self-report of having “worse” or “much worse” NSS on a five-point Likert scale (1).

Using consensus recommendations (1, 2) and prior evidence on CRS exacerbations (9–11, 13, 15, 19) we operationalized three definitions for the classification of AENSS (see online supplemental material Table S1). All definitions required participants to self-report worsened NSS in the past four weeks. “AENSS-Med” defined exacerbation was based on self-reported medication use for worsened NSS. We only used antibiotics and oral corticosteroids as qualifying medications as these are unlikely to be prescribed for viral infections, thereby minimizing potential misclassification of AENSS as common colds. This definition is also parallel to the medical management recommended for asthma control (1), since no evidence-based treatment recommendations exist for AECRS (2). We did not include inhaled corticosteroids because this would certainly misclassify AENSS as asthma exacerbations. “AENSS-Sx” was based on duration (≥ 1 week) of worsened aggregate NSS, again to minimize ascertainment of colds as AENSS, since these usually resolve within 1 week. Lastly, “AENSS-Sx-Pur” required the same criteria as “AENSS-Sx”, but additionally required self-reported worsened purulence in the past four weeks, yielding a definition with greater relative specificity. Although NSS could be worse for longer than four weeks, only a four week period was measured on questionnaires.

Evaluation of risk factors for AENSS and confounding variables

Based on previous studies (5, 18), potential risk factors and confounding variables from the EHR included: current age (years); sex; race/ethnicity (white non-Hispanic vs. all other groups); smoking status (current, former, and never); body mass index (BMI, kg/m2); Charlson comorbidity index (20); and history of receiving Medical Assistance, a surrogate for family socioeconomic status (SES) (21). Individual self-reported information was ascertained from baseline and follow-up questionnaires (Table 1).

Previous studies have shown asthma to be associated with CRS (5, 22, 23), and was therefore hypothesized to be a risk factor for AENSS. As such, individuals who experienced ≥ 1 asthma symptom (awakening at night due to wheezing; wheezing, chest tightness, or whistling in the chest when not having cold or flu; chest wheezing during or after exercise; dry cough at night apart from a cold or chest infection) at least some of the time were classified as having asthma symptoms at baseline. Migraine headaches have similarly been associated with CRS (5, 18), therefore a binary indicator for whether a subject had migraine headaches at baseline was determined as previously reported (18, 24). The continuous “Anxiety Sensitivity Index (ASI)” (25) measures how much a person fears the symptoms of anxiety, believing them to be harmful, and was created from the fall exacerbation questionnaire and included in the analysis as quintiles to help control for confounding due to an individual’s propensity to be aware of and/or over-report symptoms. Questionnaire return dates were used to define the season in which exacerbations occurred as follows: autumn, September 22 through December 21; winter, December 22 through March 21; spring, March 22 through June 21; and summer, June 22 through September 21.

Statistical analyses

Given the paucity of information regarding NSS and AENSS by EPOSS CRS status, the goals of the analysis were to 1) assess differences in NSS severity by CRS status and AENSS definition, 2) estimate the seasonal prevalence of different subgroups of AENSS (e.g., by CRS status and AENSS definition) in the source population, and 3) evaluate associations of individual self-reported risk factors and season with AENSS by CRS status.

Survey-corrected methods were used for all analyses to account for the sampling design. Design weights were the inverse product of the probability of being selected into the study and probability of responding to the baseline questionnaire. Additionally, survey weights were corrected for attrition by estimating inverse probability of censoring weights (IPCW; see online supplemental material S2). Since CRS status was not ascertained at all time-points, CRS status at the first follow-up questionnaire was used for all follow-up questionnaires. Subjects who skipped a questionnaire (23.9%) were excluded from all subsequent questionnaires to avoid intermittent missingness.

Risk factor analysis consisted of inverse-probability-weighted generalized estimating equations logistic regression models assuming an independence working correlation matrix and incorporated stabilized truncated survey weights (see online supplemental material S2). Final survey weights had a median of 2.81 and range 2.45 – 43.03. Taylor linearization was used to estimate robust variances and standard errors. Lastly, item non-response for covariates was addressed by using multiple imputation by chained equations (25 imputed data sets).

Covariates were identified as being a risk factor if they retained statistical significance in adjusted models and were not a priori determined to be a confounder. Methods for assessing model fit are limited in multiply-imputed survey-based regression models. However, model-fit was assessed by visual inspection of deviance residuals versus predicted probabilities (from weighted candidate final models) and using. Archer-Lemeshow tests for goodness of fit. To assess the utility of the multiple imputations, Monte Carlo error estimates were generated for all effect estimates and associated test statistics. All analyses were conducted in STATA 14.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Results

Description of participants

Baseline characteristics of the study population have been described elsewhere (5, 18). A total of 558 current long-term, 273 current recent, 1,644 past, and 2,261 never EPOSS CRS individuals contributed at least one observation to the analysis (Table 2). The general trends in Table 2 suggests individuals with AENSS appeared to be younger, white, female, on medical assistance, and have greater Charlson comorbidity index values, compared to those without AENSS (Table 2). The prevalence of AENSS increased from the lowest in the never group, to intermediate in the past and current recent CRS groups, to the highest in the current long-term CRS status group (Table 2). AENSS recurrence, as identified through the four follow-up questionnaires, was the least common in the never group and the most common in the current long-term CRS group (see online supplemental material Table S2).

Table 2.

Percentage (95% CI) of respondents and mean value (i.e., age, BMI) who ever met criteria for AENSS by operational criteria and by covariatesa

| Characteristic | AENSS-Medb | AENSS-Sxc | AENSS-Sx-Purd | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Never Exacerbation |

Ever Exacerbation | Never Exacerbation |

Ever Exacerbation | Never Exacerbation |

Ever Exacerbation | ||

|

| |||||||

| EPOSS CRS statuse | |||||||

| Current long-term, n = 558 | 74.1 (65.2 – 83.0)f | 25.9 (17.0 – 34.8) | 41.7 (31.0 – 52.5) | 58.3 (47.5 – 69.0) | 74.6 (67.0 – 82.5) | 25.2 (17.5 – 33.0) | |

| Current recent, n = 273 | 80.8 (71.9 – 89.8) | 19.2 (10.2 – 28.1) | 48.9 (35.4 – 62.4) | 51.1 (37.6 – 64.6) | 84.2 (77.5 – 91.0) | 15.8 (9.04 – 22.5) | |

| Past, n = 1,644 | 84.4 (80.9 – 87.9) | 15.6 (12.1 – 19.1) | 50.9 (45.2 – 56.4) | 49.2 (43.6 – 54.8) | 79.4 (74.9 – 83.8) | 20.6 (16.2 – 25.1) | |

| Never, n = 2,261 | 92.4 (90.5 – 94.3) | 7.62 (5.73 – 9.51) | 71.1 (67.8 – 74.3) | 28.9 (25.7 – 32.2) | 89.4 (87.1 – 91.6) | 10.6 (8.38 – 12.9) | |

|

|

|||||||

| p-valueg | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Age (years), mean | 55.9 (54.8 – 56.9) | 53.3 (50.7 – 55.9) | 57.1 (55.8 – 58.4) | 52.9 (51.4 – 54.5) | 56.5 (55.4 – 57.5) | 50.2 (47.8 – 52.6) | |

|

|

|||||||

| p-value | 0.08 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male, n = 1,741 | 91.2 (88.7 – 93.7) | 8.79 (6.29 – 11.3) | 68.6 (64.2 – 73.0) | 31.4 (27.0 – 35.8) | 86.6 (83.4 – 89.9) | 13.4 (10.1 – 16.6) | |

| Female, n = 2,995 | 88.4 (86.3 – 90.5) | 11.6 (9.51 – 13.7) | 62.3 (27.0 – 65.8) | 37.7 (34.2 – 41.1) | 86.2 (83.8 – 88.5) | 13.8 (11.5 – 16.2) | |

|

|

|||||||

| p-value | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.82 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| White, n = 4,399 | 89.3 (87.6 – 91.0) | 10.7 (9.01 – 12.4) | 64.2 (61.4 – 67.0) | 35.8 (33.0 – 38.6) | 86.1 (84.1 – 88.1) | 13.9 (11.9 – 15.9) | |

| Non-white, n = 337 | 91.6 (88.8 – 94.4) | 8.38 (5.56 – 11.2) | 73.9 (68.6 – 79.1) | 26.1 (20.9 – 31.4) | 91.5 (88.4 – 94.5) | 8.54 (5.50 – 11.6) | |

|

|

|||||||

| p-value | 0.19 | < 0.01 | 0.011 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Medical Assistanceh | |||||||

| Never received, n = 4,328 | 89.9 (88.2 – 91.6) | 10.1 (8.44 – 11.8) | 64.6 (61.8 – 67.4) | 35.4 (32.6 – 38.2) | 86.6 (84.6 – 88.6) | 13.4 (11.4 – 15.4) | |

| Ever received, n = 408 | 84.0 (77.4 – 90.5) | 16.0 (9.52 – 22.6) | 64.6 (54.7 – 74.5) | 35.4 (25.5 – 45.3) | 83.7 (76.5 – 90.8) | 16.3 (9.19 – 23.5) | |

|

|

|||||||

| p-value | 0.04 | 1.00 | 0.41 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Body mass index (BMI; kg/m2), mean | 29.3 (28.9 – 29.7) | 30.6 (29.4 – 31.8) | 29.6 (29.0 – 30.1) | 29.2 (28.6 – 29.8) | 29.4 (29.0 – 29.9) | 29.5 (28.5 – 30.5) | |

|

|

|||||||

| p-value | 0.05 | 0.45 | 0.79 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Charlson comorbidity index, mean | 1.10 (1.04 – 1.16) | 1.39 (1.20 – 1.58) | 1.10 (1.02 – 1.18) | 1.19 (1.09 – 1.29) | 1.13 (1.06 – 1.19) | 1.15 (1.00 – 1.30) | |

|

|

|||||||

| p-value | < 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.83 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Smoking status | |||||||

| Current, n = 581 | 87.1 (82.0 – 92.1) | 12.9 (7.86 – 18.0) | 64.5 (56.3 – 72.7) | 35.5 (27.3 – 43.7) | 88.2 (83.2 – 93.3) | 11.8 (6.69 – 16.8) | |

| Former, n = 1,460 | 91.4 (88.9 – 93.9) | 8.62 (6.14 – 11.1) | 65.9 (61.0 – 70.7) | 34.1 (29.3 – 39.0) | 87.1 (83.6 – 90.6) | 12.9 (9.43 – 16.4) | |

| Never, n = 2,695 | 88.9 (86.6 – 91.1) | 11.1 (8.87 – 13.4) | 65.0 (60.4 – 67.5) | 36.0 (32.5 – 39.6) | 85.6 (83.0 – 88.1) | 14.4 (11.9 – 17.0) | |

|

|

|||||||

| p-value | 0.22 | 0.84 | 0.61 | ||||

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; CRS = chronic rhinosinusitis; EHR = electronic health record; EPOS = European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis; SES = socioeconomic status

Unless otherwise noted, estimates are row percentages (within characteristic) of ever/never having an AENSS during follow-up; estimates may sum to >100% due to rounding

AENSS-Med= worse/much worse NSS in past 4 weeks + use of systemic corticosteroids or antibiotic prescription for worsened NSS

AENSS-Sx = worse/much worse NSS in past 4 weeks + worse over any time period up to 4 weeks + remained worse for ≥ 1-week

AENSS-Sx-Pur = worse/much worse NSS in past 4 weeks + worse over any time period up to 4 weeks + remained worse for ≥ 1 week + worse/much worse purulence

EPOSS CRS status determined using baseline and fall exacerbation questionnaires: current long-term CRS = EPOS epidemiologic criteria fulfilled at both questionnaires; current recent CRS = current CRS at fall questionnaire, but not at baseline; past CRS = EPOS epidemiologic criteria fulfilled in lifetime, but not during study; never CRS = EPOS epidemiologic criteria never met

Population-estimates were derived by using survey-corrected methods with robust standard error estimation

p-values represent differences in means (continuous variables) or Pearson’s chi-square (categorical variables)

Medical Assistance is a binary indicator of SES

Severity of nasal and sinus symptoms

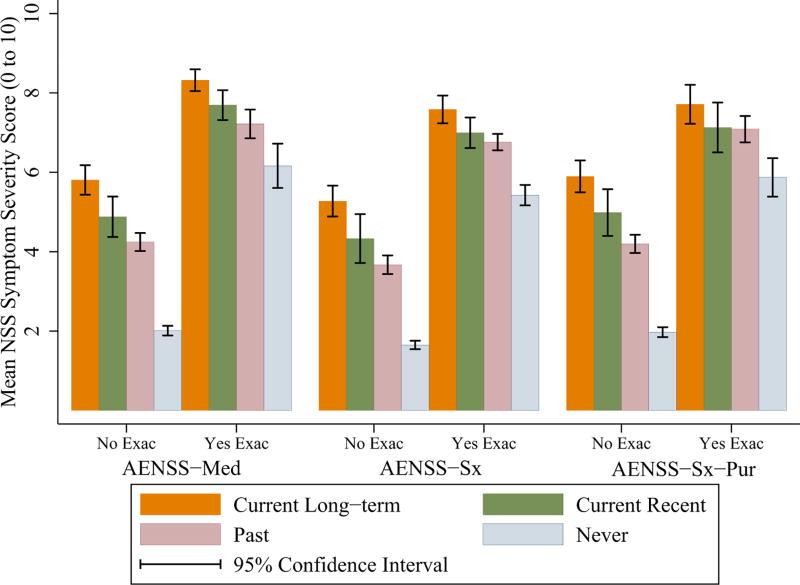

Mean NSS severity scores varied by CRS group and exacerbation status (Figure 1; online supplemental material Table S3). There were statistically significant associations between CRS status and NSS severity (Table S3). Mean NSS scores increased ordinally from the lowest score in the never CRS group to the highest score in the current long-term CRS group, where those who were having AENSS had higher NSS severity than those who were not (p < 0.001 for all CRS status groups). Mean NSS severity scores by AENSS-Med and AENSS-Sx-Pur defined exacerbations were greater than in AENSS-Sx (Figure 1; online supplemental material Table S3).

Figure 1.

Mean nasal and sinus symptom severity score on a 10-point visual analogue scale, by EPOSS defined CRS status (current long-term, current recent, past, and never) and exacerbation definition. Nasal and sinus symptoms (NSS) severity in the past 4 weeks was ascertained by self-report at each follow-up questionnaire and estimated using survey-corrected methods. Three definitions of AENSS were operationalized: (A) AENSS-Med, (B) AENSS-Sx, and (C) AENSS-Sx-Pur. Non-overlapping confidence intervals indicate statistical significance (p < 0.05). Exact p-values of pairwise statistical associations are displayed in online supplemental material Table S3.

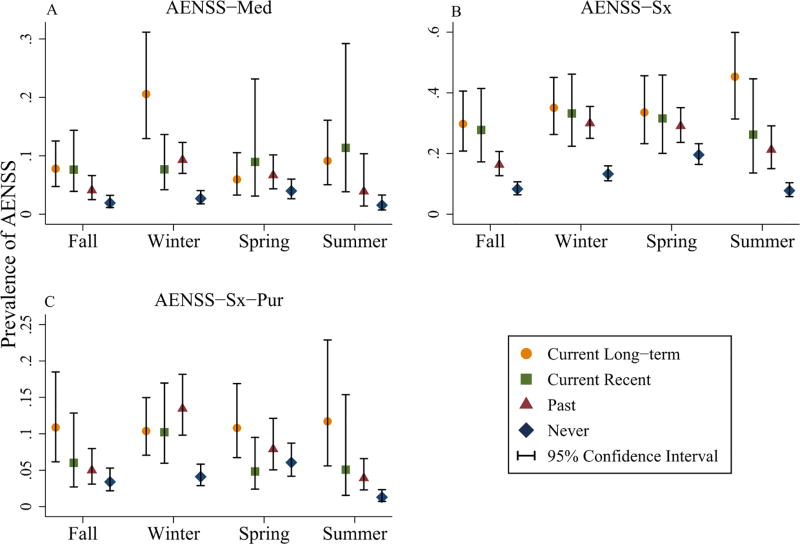

Seasonal prevalence of AENSS

Prevalence estimates of AENSS by CRS status and AENSS definition were estimated for each season (Figure 2; online supplemental material Table S4). The seasonal peak prevalence for exacerbation consistently occurred in the winter for past CRS status and in spring for never CRS status. Seasonal trends were comparable between AENSS-Sx and -Sx-Pur for the current long-term and current recent CRS groups, with peak prevalence occurring in the winter for the current recent CRS group, and a modest peak in the summer for the current long-term CRS group (Figure 2; online supplemental material Table S4).

Figure 2.

Population estimated prevalence of AENSS, by EPOSS defined CRS status (current long-term, current recent, past, and never), exacerbation definition, and season. Prevalence was estimated using survey-corrected methods. Three definitions of AENSS were operationalized: (A) AENSS-Med, (B) AENSS-Sx, and (C) AENSS-Sx-Pur.

Individual characteristic and seasonal risk factors for AENSS

Risk factor analysis proceeded with two of the three AENSS definitions (AENSS-Med and -Sx-Pur). We did not include AENSS-Sx since prevalence estimates were much greater from this definition compared to AENSS-Med and -Sx-Pur, which were both comparable, indicating a low relative specificity of AENSS-Sx compared to the other definitions. Tables 3 and 4 show the adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and 95% CIs for several covariates estimated from logistic regression models.

Table 3.

Associations with exacerbationof nasal and sinus symptoms defined by AENSS-Med

| Risk Factora | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval)b |

|---|---|

| EPOSS CRS statusc | |

| Never | |

| Fall | Ref |

| Winter | 1.48 (0.91 – 2.41) |

| Spring | 2.01 (1.22 – 3.32)** |

| Summer | 0.80 (0.42 – 1.55) |

| Past | |

| Fall | 1.28 (0.73 – 2.23) |

| Winter | 3.73 (2.30 – 6.06)*** |

| Spring | 2.18 (1.27 – 3.75)** |

| Summer | 0.94 (0.46 – 1.90) |

| Current recent | |

| Fall | 2.97 (1.30 – 6.77)* |

| Winter | 3.22 (1.59 – 6.51)** |

| Spring | 2.64 (1.11 – 6.26)* |

| Summer | 3.84 (1.33 – 11.07)* |

| Current long-term | |

| Fall | 2.55 (1.41 – 4.62)** |

| Winter | 5.96 (3.33 – 10.66)*** |

| Spring | 1.82 (0.89 – 3.74) |

| Summer | 2.89 (1.43 – 5.84)** |

|

| |

| Age (per five-year increase; years) | 0.97 (0.93 – 1.02) |

|

| |

| Sex | |

| Male | Ref |

| Female | 1.35 (1.05 – 1.74)* |

|

| |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | Ref |

| Non-white | 0.66 (0.43 – 1.00) |

|

| |

| Medical Assistanced | |

| Never received | Ref |

| Ever received | 1.37 (0.91 – 2.06) |

|

| |

| Body mass index (per 1 kg/m2 increase; BMI; kg/m2) | 1.03 (1.02 – 1.05)*** |

|

| |

| Charlson comorbidity index (per 1 unit increase in index value) | 1.09 (1.01 – 1.18)* |

|

| |

| Smoking status (baseline) | |

| Never | Ref |

| Former | 1.01 (0.77 – 1.32) |

| Current | 1.53 (1.08 – 2.18)* |

|

| |

| Asthma symptoms (baseline) | |

| None | Ref |

| At least one | 1.47 (1.14 – 1.88)** |

|

| |

| History of migraine symptoms (baseline) | |

| No | Ref |

| Yes | 1.55 (1.17 – 2.06)** |

|

| |

| Dr. diagnosed hay fever (baseline) | |

| No | Ref |

| Yes | 1.36 (1.07 – 1.74)* |

|

| |

| History of sinus surgeries (baseline) | |

| None | Ref |

| 1 | 1.46 (1.04 – 2.05)* |

| 2 or more | 1.75 (1.11 – 2.76)* |

|

| |

| Anxiety sensitivity index (quintiles) | |

| 1 | Ref |

| 2 | 0.96 (0.65 – 1.42) |

| 3 | 0.78 (0.52 – 1.17) |

| 4 | 1.18 (0.80 – 1.75) |

| 5 | 1.29 (0.89 – 1.87) |

Abbreviations: AENSS = acute exacerbation of nasal and sinus symptoms; CRS = chronic rhinosinusitis; EHR = electronic health record; EPOS = European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis; NSS = nasal and sinus symptoms

p-value<0.05,

p-value<0.01,

p-value<0.001

Risk factors selected from the electronic health record (EHR) include: age, sex, race/ethnicity, receival of Medical Assistance, and body mass index (BMI). Risk factors from self-report includes: asthma symptoms, Dr. diagnosed hay fever, history and number of sinus surgeries, and anxiety sensitivity.

Adjusted estimates from survey-corrected marginal logistic regression models with robust standard error estimation

EPOSSCRS status determined using baseline and fall exacerbation questionnaires: current long-term CRS = EPOS epidemiologic criteria fulfilled at both questionnaires; current recent CRS = current CRS at fall questionnaire, but not at baseline; past CRS = EPOS epidemiologic criteria fulfilled in lifetime, but not during study; never CRS = EPOS epidemiologic criteria never met

Medical Assistance is a binary indicator of socioeconomic status (SES)

Season: Autumn = September 22 through December 21; Winter = December 22 through March 21; Spring = March 22 through June 21; Summer = June 22 through September 21

Table 4.

Associations with exacerbation of nasal and sinus symptoms defined by AENSS Sx-Pur

| Risk Factora | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval)b |

|---|---|

| EPOSS CRS statusc | |

| Never | Ref |

| Past | 1.56 (1.18 – 2.06)** |

| Current recent | 1.56 (0.97 – 2.50) |

| Current long-term | 2.33 (1.62 – 3.34)*** |

|

| |

| Age trend (per five-year increase; years) | |

| Never | 0.85 (0.81 – 0.90)*** |

| Past | 0.92 (0.87 – 0.97)** |

| Current Recent | 0.82 (0.71 – 0.94)** |

| Current Long-term | 1.01 (0.93 – 1.10) |

|

| |

| Sex | |

| Male | Ref |

| Female | 1.09 (0.86 – 1.38) |

|

| |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | Ref |

| Non-white | 0.52 (0.34 – 0.79)** |

|

| |

| Medical Assistanced | |

| Never received | Ref |

| Ever received | 0.95 (0.67 – 1.35) |

|

| |

| Body mass index (per 1 kg/m2 increase; BMI; kg/m2) | 1.02 (1.01 – 1.03)** |

|

| |

| Charlson comorbidity index (per 1 unit increase in index value) | 0.94 (0.88 – 1.02) |

|

| |

| Asthma symptoms (baseline) | |

| None | Ref |

| At least one | 1.68 (1.32 – 2.15)*** |

|

| |

| History of migraine symptoms (baseline) | |

| No | Ref |

| Yes | 1.34 (1.00 – 1.79) |

|

| |

| Dr. diagnosed hay fever (baseline) | |

| No | Ref |

| Yes | 1.36 (1.08 – 1.71)* |

|

| |

| History of sinus surgeries (baseline) | |

| None | Ref |

| 1 | 1.30 (0.95 – 1.78) |

| 2 or more | 1.58 (1.06 – 2.35)* |

|

| |

| Anxiety sensitivity index (quintiles) | |

| 1 | Ref |

| 2 | 1.00 (0.69 – 1.44) |

| 3 | 0.92 (0.63 – 1.34) |

| 4 | 1.19 (0.83 – 1.71) |

| 5 | 1.36 (0.95 – 1.95) |

|

| |

| Seasone | |

| Fall | Ref |

| Winter | 2.17 (1.67 – 2.82)*** |

| Spring | 1.71 (1.28 – 2.29)*** |

| Summer | 0.88 (0.62 – 1.25) |

Abbreviations: AENSS = acute exacerbation of nasal and sinus symptoms; CRS = chronic rhinosinusitis; EHR = electronic health record; EPOS = European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis; NSS = nasal and sinus symptoms

p-value<0.05,

p-value<0.01,

p-value<0.001

Risk factors selected from the electronic health record (EHR) include: age, sex, race/ethnicity, receival of Medical Assistance, and body mass index (BMI). Risk factors from self-report includes: asthma symptoms, Dr. diagnosed hay fever, history and number of sinus surgeries, and anxiety sensitivity.

Adjusted estimates from survey-corrected marginal logistic regression models with robust standard error estimation

EPOSS CRS status determined using baseline and fall exacerbation questionnaires: current long-term CRS = EPOS epidemiologic criteria fulfilled at both questionnaires; current recent CRS = current CRS at fall questionnaire, but not at baseline; past CRS = EPOS epidemiologic criteria fulfilled in lifetime, but not during study; never CRS = EPOS epidemiologic criteria never met

Medical Assistance is a binary indicator of socioeconomic status (SES)

Season: Autumn = September 22 through December 21; Winter = December 22 through March 21; Spring = March 22 through June 21; Summer = June 22 through September 21

Several significant and elevated odds ratios were identified in relation to AENSS-Med (Table 3) for higher BMI, being a current smoker, having asthma or migraine symptoms at baseline, doctor diagnosed hay fever, having had two or more sinus surgeries, and winter season. As CRS status was found to modify associations of season with AENSS-Med, associations are displayed within strata of CRS status (Table 3).

Elevated odds ratios of risk factors with AENSS-Sx-Pur (Table 4) were found for white race/ethnicity, BMI, having asthma symptoms at baseline, doctor diagnosed hay fever, history of having two or more sinus surgeries, and season (winter and spring). Age modified associations of CRS status with AENSS, therefore CRS status associations are displayed at the grand mean age (55.1 years). Subjects with either past or current long-term CRS had increased odds of AENSS-Sx-Pur. The interaction between age and CRS status was observed as a linear reduction in odds of AENSS-Sx-Pur with higher ages for all CRS status groups, except current long-term CRS (Table 4).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study of the epidemiology of AENSS by EPOSS CRS status, while evaluating three definitions of AENSS. There were several potentially important findings by season and CRS status, offering possible etiologic and diagnostic insights relevant to clinical management of AENSS. NSS and AENSS were common among all subjects; NSS and AENSS severity were worst in subjects with current, long-term CRS; prevalence of AENSS as measured by AENSS-Sx was almost 2-fold higher than by -Sx-Pur and -Med; there were clear seasonal prevalence differences observed using the different definitions of AENSS; and risk factor analysis showed differing associations depending on the definition of AENSS, particularly that odds of AENSS-Sx-Pur did not decline with increasing age in current long-term EPOSS subjects but did in all other EPOSS groups.

In the absence of consensus on how to measure AENSS, we operationalized three definitions that first identified worsening of symptoms (e.g., NSS in past four weeks reported as worse or much worse than “usual”) and then applied criteria that would differentially maximize sensitivity (the proportion of people with an exacerbation who met the AENSS definition), positive predictive value (PPV; the proportion of people who met the AENSS definition who had an exacerbation), and clinical similarity to how asthma exacerbation is often defined in epidemiologic studies. AENSS-Sx was the most sensitive (and by definition, least specific) definition, and is useful for researchers wanting to estimate the prevalence of AENSS while avoiding under-estimation. Of the three definitions, AENSS-Sx-Pur should have the highest PPV, and therefore may be the best for risk factor analysis since its lower misclassification will minimize bias in effect estimates towards the null. Lastly, a medication-based AENSS definition (AENSS-Med) for CRS requires care-seeking behavior for symptoms that are generally not life-threatening, thus making a medication-based definition much more reliant on health care access and delivery.

Although overall prevalence estimates for AENSS-Med and -Sx-Pur were comparable, there was little overlap in individuals ascertained by the two definitions, with only 31% of AENSS-Sx-Pur events additionally meeting criteria for AENSS-Med (see online supplemental material Table S5). Discordance could be due to AENSS-Med being influenced by an individual’s propensity to seek and be provided with medical care.

AENSS occurred in all CRS status groups, but prevalence was higher and severity worse among subjects with past or current (long-term and recent) CRS. The absolute change in severity during an AENSS was largest among subjects who never met EPOSS CRS criteria, possibly due to a ceiling effect in NSS severity among individuals with current or past CRS.

AENSS prevalence was greatest in the winter and spring for the past and never CRS groups, respectively, across all three AENSS definitions. This suggests exacerbations might be driven by viral infections in the winter (e.g. rhinoviruses (26–30)) or seasonal allergens and allergic rhinitis, for those with or without a history of CRS, respectively. No consistent seasonal patterns of AENSS were observed for the current CRS status groups across all three definitions of AENSS; however, a peak prevalence occurred in the winter or summer (AENSS-Med and AENSS-Sx/Sx-Pur, respectively) for the current recent CRS group. Prevalence of AENSS-Med was greatest in the current long-term CRS status group and occurred in the winter season, yet no major seasonal changes in AENSS-Sx/Sx-Pur were observed for this group, apart from modest associations with summer season. This could be due to residual selection bias due to loss-to-follow-up unaccounted for by the weighting procedure, or could reflect specific seasonal triggers relevant to this subgroup (e.g. ragweed). It is possible that individuals with a long-term history of current CRS are more likely to be prescribed medications for NSS in the winter, although NSS may not necessarily be more severe (given the lack of observed associations between season and AENSS-Sx/-Sx-Pur in this group). This may also reflect underlying pathobiology relevant to triggers of exacerbation in this group, since medical management would depend on the trigger (e.g. infections vs. grass pollen).

We identified clinical and seasonal factors associated with AENSS. CRS status, increased BMI, asthma symptoms, hay fever, migraine symptoms, history of sinus surgeries, and season were associated with AENSS by both Med and Sx-Pur defined exacerbation. Our findings with BMI are similar to those found previously with CRS (31, 32) and other otorhinolaryngological (32) diseases, possibly due to chronic low-grade inflammation associated with obesity (33, 34). Asthma (1, 2, 22, 23) and hay fever (1, 2, 22, 23) have been associated with CRS; however, symptom overlap between these conditions could indicate measurement error in EPOSS criteria. To address this issue, we evaluated whether hay fever or asthma modified associations of CRS status with AENSS. As we found no evidence for this, we included hay fever and asthma diagnoses as covariates in regression models without further stratification and statistical significance suggests indication of the unified airways disease concept. The relationship between migraines and NSS has been observed in previous studies (5, 23), but could be due to misclassification of overlapping symptoms or biologic pathways (35–37), or both. Sinus surgery was also associated with AENSS and could be due to bacterial infections in some CRS patients (38), or be a proxy for individuals with recalcitrant CRS or persistent ARS, who are more likely to be aware of the severity of sinus symptoms over time.

Females were more likely to have AENSS-Med than males, possibly due to residual confounding associated with medical-seeking and -prescribing behaviors (39), since this association was only modestly observed in the AENSS-Sx-Pur model; however, female sex has been associated with CRS symptoms in other studies (5, 40, 41). Non-white race/ethnicity was associated with reduced odds of both AENSS definitions, though only statistically significant in the AENSS-Sx-Pur model. Lastly, never smokers were less likely to have AENSS-Med, compared to current smokers, although no association with smoking status and AENSS-Sx-Pur was observed. The odds of AENSS-Sx-Pur declined with higher ages, excluding the current long-term CRS status group, possibly due to differential susceptibility to viral infections which precede bacterial infections and decrease with increasing age (42). Yet, individuals with long-term CRS may be at risk of developing viral respiratory infections even at older ages due to compromised epithelial barrier function (43, 44), which can accompany CRS (1, 2, 45), suggestive of a disease progressive model in those with persistent CRS.

Our study had several strengths, including study of the general population in the region representing the full spectrum of diseases with NSS, longitudinal design (the first to our knowledge), large sample size, and evaluation of a relevant set of individual-reported potential risk factors for AENSS, as well as season. We also used several definitions of AENSS to comparatively assess their utility in epidemiologic research, as advised by ICAR (2). Our study is not without limitations, however. We used a definition of CRS which did not include confirmation of inflammation by endoscopy or CT scan so we were unable to classify individuals with clinical CRS. Second, both CRS status and self-reported individual characteristics were selected from the same questionnaires; as such there is the potential for spurious associations between them, since they are dependent on how an individual interprets and responds to the questions. However, a strength of this study is the inclusion of the ASI as a covariate, which adjusts for an individual’s propensity to over-report symptoms and comorbidities. Therefore, the possibility of false associations from same source bias was mitigated. Furthermore, we used weighting methods and multiple imputation to adjust for non-response and potential selection bias.

In summary, our study found that NSS and AENSS were common in the general population. NSS and AENSS severity were worse across categories of EPOSS CRS, peaking among current long-term CRS. Seasonal exacerbation prevalence depended on the AENSS definition and differed by EPOSS CRS status. Results suggest that a high PPV definition (e.g., AENSS-Sx-Pur) may provide the best balance between a sensitive definition and one which is clinically meaningful.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by grant U19AI106683 (Chronic Rhinosinusitis Integrative Studies Program [CRISP] from the National Institutes of Health, and by a grant from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (T42 OH0008428) to the Johns Hopkins University Education and Research Center for Occupational Safety and Health.

Footnotes

Competing financial interests: The authors declare they have no actual or potential competing financial interests.

Author contributions:

All authors participated in drafting/revision of the manuscript, final approval of the manuscript, and interpretation of findings. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. JRK, AGH, ASS, BKT, RPS, RCK, WFS, and BSS were involved in the conception and design of the study. JRK, AGH, KBR, and BSS acquired and analyzed the data.

References

- 1.Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Mullol J, Bachert C, Alobid I, Baroody F, et al. European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2012. Rhinology Supplement. 2012 Mar;(23):3. p preceding table of contents, 1–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orlandi RR, Kingdom TT, Hwang PH, Smith TL, Alt JA, Baroody FM, et al. International Consensus Statement on Allergy and Rhinology: Rhinosinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016 Feb;6(Suppl 1):S22–209. doi: 10.1002/alr.21695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moorman JE, Akinbami LJ, Bailey CM, Zahran HS, King ME, Johnson CA, et al. National surveillance of asthma: United States, 2001–2010. Vital & health statistics Series 3, Analytical and epidemiological studies. 2012 Nov;(35):1–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hastan D, Fokkens WJ, Bachert C, Newson RB, Bislimovska J, Bockelbrink A, et al. Chronic rhinosinusitis in Europe--an underestimated disease. A GA(2)LEN study. Allergy. 2011 Sep;66(9):1216–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirsch AG, Stewart WF, Sundaresan AS, Young AJ, Kennedy TL, Scott Greene J, et al. Nasal and sinus symptoms and chronic rhinosinusitis in a population-based sample. Allergy. 2017 Feb;72(2):274–81. doi: 10.1111/all.13042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Remenschneider AK, Metson RB. Quality of Life in Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2012;147:P253–P4. doi: 10.1177/0194599817706929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gliklich RE, Metson R. The Health Impact of Chronic Sinusitis in Patients Seeking Otolaryngologic Care. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 1995;113(1):104–9. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989570152-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caulley L, Thavorn K, Rudmik L, Cameron C, Kilty SJ. Direct costs of adult chronic rhinosinusitis by using 4 methods of estimation: Results of the US Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2015 Dec;136(6):1517–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brook I. Bacteriology of chronic sinusitis and acute exacerbation of chronic sinusitis. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 2006 Oct;132(10):1099–101. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.10.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikeda K, Yokoi H, Kusunoki T, Saitoh T, Yao T, Kase K, et al. Bacteriology of recurrent exacerbation of postoperative course in chronic rhinosinusitis in relation to asthma. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2011 Aug;38(4):469–73. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merkley MA, Bice TC, Grier A, Strohl AM, Man LX, Gill SR. The effect of antibiotics on the microbiome in acute exacerbations of chronic rhinosinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015 Oct;5(10):884–93. doi: 10.1002/alr.21591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Divekar RD, Samant S, Rank MA, Hagan J, Lal D, O'Brien EK, et al. Immunological profiling in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps reveals distinct VEGF and GM-CSF signatures during symptomatic exacerbations. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015 Apr;45(4):767–78. doi: 10.1111/cea.12463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rank MA, Hagan JB, Samant SA, Kita H. A proposed model to study immunologic changes during chronic rhinosinusitis exacerbations: data from a pilot study. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2013 Mar-Apr;27(2):98–101. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2013.27.3850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaudhry AL, Chaaban MR, Ranganath NK, Woodworth BA. Topical triamcinolone acetonide/carboxymethylcellulose foam for acute exacerbations of chronic rhinosinusitis/nasal polyposis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2014 Jul-Aug;28(4):341–4. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2014.28.4053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solares CA, Batra PS, Hall GS, Citardi MJ. Treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis exacerbations due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with mupirocin irrigations. Am J Otolaryngol. 2006 May-Jun;27(3):161–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wahl KJ, Otsuji A. New medical management techniques for acute exacerbations of chronic rhinosinusitis. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003 Feb;11(1):27–32. doi: 10.1097/00020840-200302000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casale M, Sabatino L, Frari V, Mazzola F, Dell'Aquila R, Baptista P, et al. The potential role of hyaluronan in minimizing symptoms and preventing exacerbations of chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2014 Jul-Aug;28(4):345–8. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2014.28.4045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tustin AW, Hirsch AG, Rasmussen SG, Casey JA, Bandeen-Roche K, Schwartz BS. Associations between Unconventional Natural Gas Development and Nasal and Sinus, Migraine Headache, and Fatigue Symptoms in Pennsylvania. Environ Health Perspect. 2016 Aug 25; doi: 10.1289/EHP281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rank MA, Wollan P, Kita H, Yawn BP. Acute exacerbations of chronic rhinosinusitis occur in a distinct seasonal pattern. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2010 Jul;126(1):168–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of chronic diseases. 1987;40(5):373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Casey JA, Curriero FC, Cosgrove SE, Nachman KE, Schwartz BS. High-density livestock operations, crop field application of manure, and risk of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection in Pennsylvania. JAMA Intern Med. 2013 Nov 25;173(21):1980–90. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.10408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirsch AG, Yan XS, Sundaresan AS, Tan BK, Schleimer RP, Kern RC, et al. Five-year risk of incident disease following a diagnosis of chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergy. 2015 Dec;70(12):1613–21. doi: 10.1111/all.12759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan BK, Chandra RK, Pollak J, Kato A, Conley DB, Peters AT, et al. Incidence and associated premorbid diagnoses of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2013 May;131(5):1350–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lipton RB, Dodick D, Sadovsky R, Kolodner K, Endicott J, Hettiarachchi J, et al. A self-administered screener for migraine in primary care: The ID Migraine validation study. Neurology. 2003 Aug 12;61(3):375–82. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000078940.53438.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reiss S, Peterson RA, Gursky DM, McNally RJ. Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency and the prediction of fearfulness. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1986;24(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(86)90143-9. //; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abshirini H, Makvandi M, Seyyed Ashrafi M, Hamidifard M, Saki N. Prevalence of rhinovirus and respiratory syncytial virus among patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Jundishapur journal of microbiology. 2015 Mar;8(3):e20068. doi: 10.5812/jjm.20068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cho GS, Moon B-J, Lee B-J, Gong C-H, Kim NH, Kim Y-S, et al. High Rates of Detection of Respiratory Viruses in the Nasal Washes and Mucosae of Patients with Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2013;51(3):979–84. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02806-12. 10/23/received 12/03/rev-request 01/08/accepted; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang JH, Kwon HJ, Jang YJ. Rhinovirus enhances various bacterial adhesions to nasal epithelial cells simultaneously. Laryngoscope. 2009 Jul;119(7):1406–11. doi: 10.1002/lary.20498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang JH, Kwon HJ, Jang YJ. Rhinovirus upregulates matrix metalloproteinase-2, matrix metalloproteinase-9, and vascular endothelial growth factor expression in nasal polyp fibroblasts. Laryngoscope. 2009 Sep;119(9):1834–8. doi: 10.1002/lary.20574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lima JT, Paula FE, Proenca-Modena JL, Demarco RC, Buzatto GP, Saturno TH, et al. The seasonality of respiratory viruses in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2015 Jan-Feb;29(1):19–22. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2015.29.4129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhattacharyya N. Associations between obesity and inflammatory sinonasal disorders. Laryngoscope. 2013 Aug;123(8):1840–4. doi: 10.1002/lary.24019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim TH, Kang HM, Oh IH, Yeo SG. Relationship Between Otorhinolaryngologic Diseases and Obesity. Clinical and experimental otorhinolaryngology. 2015 Sep;8(3):194–7. doi: 10.3342/ceo.2015.8.3.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nathan C. Epidemic inflammation: pondering obesity. Molecular medicine (Cambridge, Mass) 2008 Jul-Aug;14(7–8):485–92. doi: 10.2119/2008-00038.Nathan. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gregor MF, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammatory mechanisms in obesity. Annual review of immunology. 2011;29:415–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perry BF, Login IS, Kountakis SE. Nonrhinologic headache in a tertiary rhinology practice. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004 Apr;130(4):449–52. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eross E, Dodick D, Eross M. The Sinus, Allergy and Migraine Study (SAMS) Headache. 2007 Feb;47(2):213–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cady RK, Schreiber CP. Sinus headache or migraine? Considerations in making a differential diagnosis. Neurology. 2002 May 14;58(9 Suppl 6):S10–4. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.9_suppl_6.s10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhattacharyya N, Gopal HV, Lee KH. Bacterial infection after endoscopic sinus surgery: a controlled prospective study. Laryngoscope. 2004 Apr;114(4):765–7. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200404000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beule A. Epidemiology of chronic rhinosinusitis, selected risk factors, comorbidities, and economic burden. GMS current topics in otorhinolaryngology, head and neck surgery. 2015;14:Doc11. doi: 10.3205/cto000126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen Y, Dales R, Lin M. The epidemiology of chronic rhinosinusitis in Canadians. Laryngoscope. 2003 Jul;113(7):1199–205. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200307000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shashy RG, Moore EJ, Weaver A. Prevalence of the chronic sinusitis diagnosis in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 2004 Mar;130(3):320–3. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.3.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stover CS, Litwin CM. The Epidemiology of Upper Respiratory Infections at a Tertiary Care Center: Prevalence, Seasonality, and Clinical Symptoms. Journal of Respiratory Medicine. 2014;2014:8. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cho SH, Hong SJ, Han B, Lee SH, Suh L, Norton J, et al. Age-related differences in the pathogenesis of chronic rhinosinusitis. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2012 Oct 01;129(3):858–60.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cho SH, Kim DW, Lee SH, Kolliputi N, Hong SJ, Suh L, et al. Age-Related Increased Prevalence of Asthma and Nasal Polyps in Chronic Rhinosinusitis and Its Association with Altered IL-6 Trans-Signaling. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 2015 Nov;53(5):601–6. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0207RC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lam K, Schleimer R, Kern RC. The Etiology and Pathogenesis of Chronic Rhinosinusitis: a Review of Current Hypotheses. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015 Jul;15(7):41. doi: 10.1007/s11882-015-0540-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.