Abstract

Criminal offenders often turn to social networks to gain access to firearms, yet we know little about how networks facilitate access to firearms. This study conducts a network analysis of a co-offending network for the City of Chicago to determine how close any offender may be to a firearm. We use arrest data to recreate the co-offending network of all individuals who were arrested with at least one other person over an eight-year period. We then use data on guns recovered by the police to measure potential network pathways of any individual to known firearms. We test the hypothesis that gangs facilitate access to firearms and the extent to which such access relates to gunshot injury among gang members. Findings reveal that gang membership reduces the potential network distance (how close someone is) to known firearms by 20% or more, and regression results indicate that the closer gang members are to guns, the greater their risk of gunshot victimization.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11524-018-0259-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Street gangs, Social networks, Gun markets, Guns, Gun injuries

Introduction

Many individuals at the highest risk of gun violence victimization are often prohibited by federal law from owning a firearm: convicted felons and those with a criminal history [1]. Studies have long shown that the most likely victims of gun homicide are those with contact with the criminal justice system, especially those arrested by the police [2–4]. Given the spatial concentration of fatal and non-fatal shootings within socially disadvantaged neighborhoods [5–8] and small social networks [3, 9], this means that young minority men are also most likely to live, go to school, and work in neighborhoods with the highest levels of gun violence. The irony of being at extreme risk and yet prohibited to legally purchase a firearm is not lost on those whose lives are at stake. Felon status in no way diminishes the desire for protection or the perceived use of a firearm for that purpose, but it does push the process of acquiring a firearm into underground and illegal gun markets [10, 11].

Protection—and self-defense—is one of the most common reasons for gun ownership in the USA [12, 13]. Protection is also one of the primary reasons young people give for joining a street gang: a deep-seated desire to feel safe in neighborhoods and contexts with high levels of crime and violence [14–16]. Qualitative research has shown that gangs can act as an important source of guns for this vulnerable population [10]. Gangs as collectivities, then, might act as a point source of guns for its members who might ask to borrow a gun in times of troubles, or else turn to other armed gang members to help settle disputes [20]. Despite members’ perception of the possible protective features of gangs, gang membership actually increases rates of violent victimization of its members—sometimes exponentially—and gangs are also disproportionately involved in gun-involved crimes and violence [15, 17–19].

This study analyzes the extent to which gangs in Chicago might facilitate access to firearms within high-risk networks of offenders. Situated within the growing field of network science, this study begins by re-creating the co-offending network of all individuals in the City of Chicago who were arrested with at least one other person between the years 2006 and 2014. We then identify which individuals in this network possessed a firearm that was recovered by the police or else involved in a crime in which a gun was present. Our first analytic objective is to determine just how close any co-offender is to a firearm—literally, how many co-arrest “handshakes” away an individual is from a known illegal firearm. From there, we determine how, if at all, police-identified gang membership may be associated with increased access to firearms and then assess whether or not this increased access to guns is associated with increased victimization among gang members.

Gangs as Salient Contexts for Facilitating Illegal Access to Guns

Despite multiple illegal sources of firearms for those involved in crime [21], ethnographic research suggests that it may be challenging for criminals to easily access firearms in Chicago. Philip Cook and colleagues found evidence of considerable frictions in the underground market for guns in Chicago due primarily to the fact that the underground gun market was both illegal and “thin”—the number of buyers, sellers, and total transactions was small, and relevant information on reliable sources of guns were scarce [10]. Street gangs, Cook et al. found, helped to overcome these market frictions, but the gangs’ economic interests caused gang leaders to limit supply primarily to gang members—transactions were usually loans or rentals with strings attached [10].

There is good reason to consider gangs and other high-risk groups as important contexts in their own right in shaping demand for guns and facilitating access to guns. Research has shown gangs to be critical mechanisms in explaining both the stability of gun violence in disadvantaged neighborhoods and the transmission of gun violence via spatial and social network processes [22, 23]. In addition to their disproportionate use of guns in homicide [24, 25], gangs further seem to influence the gun carrying patterns of the people involved in them. One way in which gangs might facilitate access to guns is by developing more robust flows of guns into members’ hands and maintaining a larger stock of firearms through individual and collective means—i.e., the gang, as a group, may have greater potential as a collective to acquire and to hang on to guns or else have greater access illegal markets. If this is true, then gangs may very well facilitate individual members’ access to illegal guns.

The available evidence also suggests that gangs assist in individual gun acquisition by reducing the search costs of finding a gun. Gangs may collectively hold stockpiles of guns from which individuals could acquire firearms, serve as connections to illegal gun brokers and traffickers, or provide information on the pathways through which guns could be acquired [10, 26, 27].

Network science offers one way to understand the ways in which individuals search for information or goods [28]—especially illegal goods and services [29]. Individuals acquire and evaluate information through informal contacts with friends, associates, and co-workers, asking people they think are likely to have the requested information. This process tends to be inefficient, in large part because of information asymmetries. We argue that gangs may help individuals looking to acquire guns with illegal market searches. While our present data does not allow us to differentiate specific gun acquisition mechanisms, our use of network analysis is intended to analyze potential pathways to a gun based on prior co-offending ties.

Data and Methods

This study has two main analytic objectives. First, we aim to determine how close any individual in the co-arrest network is to a known firearm and the role gangs might play in facilitating access to firearms. Second, we run a series of linear regression models to determine how (if at all) the social distance to known firearm among gang members is related to gunshot victimization. Using individual-level data, we regress the probability of victimization on the distance to the nearest known gun, measured as the shortest distance of that gun from individual gang members. Given the well-documented racial disparities in gun violence victimization [30] as well as possible variation in the organizational capacity of gangs [31], our models also consider how access to guns and the likelihood of victimization could also vary by the dominant race and size of a gang.

Data used in this study come from four sources provided by the Chicago Police Department (CPD): (1) arrest records, (2) gang membership rosters, (3) fatal and non-fatal victimization data, and (4) gun recovery data.

Building Co-offending Networks

Following previous research [3, 9], we use incident-level arrest data for the entire City of Chicago to create the co-offending networks that are the basis of our analyses. These data include all arrests by CPD that occurred from January 1, 2006, to September 30, 2013 (N = 967,453). Arrest information includes socio-demographic information for the individuals arrested, including their gender, age, and race. Co-offending networks are created by first identifying all unique individuals in the arrest records and then identifying all instances of co-offending, incidents in which two or more individuals were arrested for the same crime [3]. In total, 396,042 unique individuals were identified in the arrest records, of which approximately 45% (N = 188,338) were arrested in an incident involving two or more individuals (i.e., are not isolates in the network). Ties that might capture a victim-offender relationship—such as two individuals charged for a fight—are excluded from the current analyses. Networks are created by linking individuals through incidents of co-arrest based on the assumption that individuals engaging in a crime together are “associated” with each other or, more precisely, that they engage in risky behavior together.

There are 188,338 non-isolates in the total network, i.e., individuals with at least 1 co-offending tie to another person. The complete network contains 26,150 unique components (subgraphs) ranging in size from 2 (a dyad) to 123,506 (the largest connected component). Our analysis is limited to the largest connected component (LCC) which contains 66% of all individuals in the network, 13% of all recovered firearms, and nearly 77% of all individuals in the data whomever possessed one of the firearms at all. Seventy-two percent of all gunshot victims in the network can be located in the LCC and just over one quarter of all individuals in the LCC were listed as gang members by the police at some point during the observation period (N = 34,106).

Locating the Gang Members, Victims, and Guns in the Network

After creating the co-offending networks, we used the remaining three sources of data to locate which individuals in the LCC were gang members, which were victims of gunshot injuries, and which had physically possessed one of the illegal guns recovered by CPD. Gang membership of individuals in the network is identified using a “gang admissions” list provided by CPD. In these data, gang membership is determined by either self-identification by the individual or else through identification by police or correctional personal during the course of investigation or during jail in-take. In total, 34,106 individuals—20% of the total LCC—were identified as members of a street gang. These gang members belonged to seventy-eight different gangs. In the ensuing analyses, we use a binary indicator of whether or not an individual in the network was a gang member (1 = yes, 0 = no).

Second, we identified 12,854 individuals in the network who had been victims of fatal and non-fatal shootings based on victimization data of all 20,417 fatal or non-fatal gunshot injuries reported to CPD between January 1, 2006, and September 30, 2013. In other words, approximately 63% of all gunshot victims during this time period can be located in the co-offending network. Nearly all of these gunshot victims—72%—are in the LCC. We use a binary indicator of whether or not an individual in the LCC was a victim of a shooting as one of our main dependent variables (1 = yes, 0 = no).

Finally, we determined whether or not an individual in the network had access to a firearm at some point during the observation period using data on all recovered firearms in Chicago from January 1, 2006, to September 15, 2012, to attribute specific firearms to people in the co-offending network. In total, 28,813 firearms were recovered by CPD and sent to ATF for tracing; 4826 firearms (or roughly 17% of all recovered firearms) could be located to unique individuals in the network. Importantly, 13% of all firearms and 77% of all individuals to whom a recovered firearm can be linked can be in the largest component. We use a binary indicator of whether or not each individual in the network at any time possessed one of these recovered firearms (1 = yes, 0 = no).

While the total population of guns is unknown, these data on known guns provide at least a snapshot of some of the known guns and gun users in Chicago during the observation period. On the one hand, gun recovery information most likely underestimates the true populations of guns within the network since this metric requires the physical recovery of the firearm. While such a metric provides a direct link to a known firearm, it excludes a large number of crimes in which a gun was most likely used but not recovered. Relying solely on recovery data thus creates potential underestimation by omission. On the other hand, using firearm-related arrests as an indicator of gun possession may overestimate gun possession. For example, the same gun might very well have been used by different individuals in multiple crimes, especially in the gang context. While we cannot resolve such a debate with the state of existing data, our analyses provide estimates on the guns currently in circulation among active gun users in a city with a high rate of gun violence. As a robustness check, we re-ran all of our analyses relying on arrest records to identify those individuals who were involved in a gun-related crime but which a firearm may or may not have been recovered (see Supplemental Materials); all of the results are identical in statistical significance and direction from those presented in the main article.

Measuring Access to Guns within the Co-offending Network

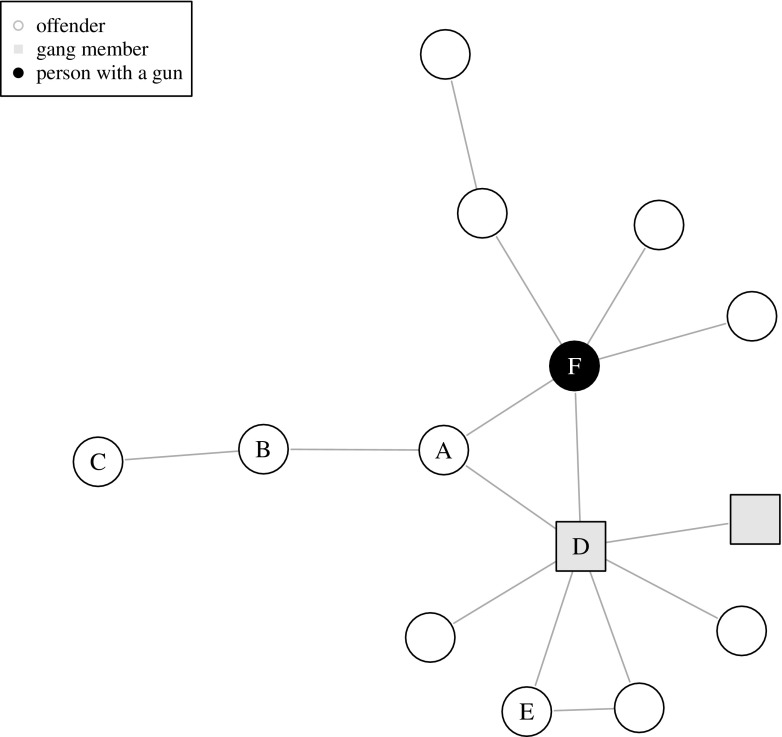

One of this study’s main objectives is to provide a network metric of any individual’s distance to a known gun within the network and the extent to which gang members might provide quicker access. We create a measure of the shortest path or minimum geodesic distance to a gun for each individual within the LCC using R software [32] and add-on packages designed for working with network data [33] and large matrices [34, 35]. This metric measures the shortest network distance (in ties) from each individual to another individual in the network who possessed a gun. The shorter the distance, the closer any individual is to a gun. For example, a distance of 2 means that an individual is 2 co-offending ties away from the nearest gun (an associate’s associate). Figure 1 visualizes this metric by displaying a small hypothetical network. This network is made up of fourteen individuals (nodes), two of whom are members of a gang, and one of whom had possession of a gun recovered by police. In this network, A, D, and F are a central “clique” in the network—a closed triangle all tied directly to each other—with several direct and indirect ties to the other people.

Fig. 1.

Example network of offenders, gang members, and a person with a gun

The central argument of this paper is that the shape of such networks influences (a) access to firearms and (b) the risk of gunshot victimization. If A or D knows that F has a gun, and they need access to a gun, they might simply ask F: both A and D have a minimum distance to a gun of 1. But, more distal people—such as B, C, or E—do not have direct access to F; if they need access, they would have to go through an intermediary, like A or D, and the distance to a gun would be longer. Gangs, we argue, should decrease such distances, even for those who might not be gang members. In Fig. 1, for example, gang member D sits on several different paths acting as a network broker between other gang members, non-gang members, and a person who has an actual gun (F). To be sure, gang boundaries are not impenetrable and individuals often have personal or other ties that span group distinctions [18, 31]. We attempt to account for this by allowing our network metric to capture any individual’s social distance to any person in the network irrespective of gang status or specific membership and controlling for gang-specific effects in subsequent analyses.

Predicting Individual Gang Member Victimization

Our final stage of analyses determines if gang members that are closer to guns are more likely to be shot. Namely, gang members who are in groups with greater access to guns are, by extension, potentially exposed to more situations in which guns might be used to settle disputes [45]. The heightened chance of gunfire, in turn, increases the probability that socially connected gang members will suffer a gunshot injury. We model this hypothesis using individual-level data about gang members and a series of linear regression models. We regress the probability of victimization on the distance to the nearest gun. Noting that race was an important source of variation in the descriptive analyses, we run a second model that includes a dummy variable for members of black gangs—gangs in which the majority of members are black (1 = yes, 0 = no). Including the dummy variable allows members of black gangs to have a different intercept in the model. To see if the differences between members of black gangs and other gangs are attributable to systematic differences in the size of these gangs, we run a third model that includes the size of the member’s gang. Finally, in a fourth model, we add an interaction term between black gangs and gang size, which allows for the possibility that gunshot victimization and the size of a gang are fundamentally different for members of black gangs than for members of other gangs.

Results

Summary Statistics and Distance to a Gun

Table 1 provides summary statistics for individuals in the LCC differentiated by gang membership. The average age of individuals is 26.9 years (SD = 11.6). The network is overwhelming male (81.9%) and black non-Hispanic (77%). Approximately 17% of all individuals and 19% of the gang members are white Hispanic. While 7.5% of the entire LCC have been victims of a gunshot injury, that percentage nearly doubles to 14.5% for gang members.

Table 1.

Summary statistics for the network

| All | Gang members | Not in Gang | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percent or mean (SD; min, max) |

Percent or mean (SD; min, max) |

Percent or mean (SD; min, max) |

|

| Linked to a recovered gun | 3.0% | 5.0% | 2.3% |

| Gunshot victim | 7.5% | 14.5% | 4.9% |

| Sex (male) | 81.9% | 97.8% | 75.8% |

| Age (in years) | 26.9 (11.6; 6, 84) | 24.8 (9.1; 10, 72) | 27.7 (12.3; 6, 84) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Black non-Hispanic | 77.0% | 77.6% | 76.7% |

| White Hispanic | 17.1% | 19.4% | 16.2% |

| White non-Hispanic | 5.0% | 2.1% | 6.1% |

| Asian Pacific Islander | 0.4% | 0.2% | 0.4% |

| Native American | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Multi-racial | 0.5% | 0.6% | 0.5% |

| Gang member | 27.6% | 100.0% | 0.0% |

| Degree (N of co-arrest ties) | 5.9 (8.8; 1, 173) | 9.0 (9.7; 1, 167) | 4.8 (8.2; 1, 173) |

| Geodesic distance to the nearest recovered gun | 2.5 (1.3; 0, 14) | 2.0 (1.1; 0, 13) | 2.7 (1.3; 0, 14) |

| n = 123,506 | n = 34,106 | n = 89,400 | |

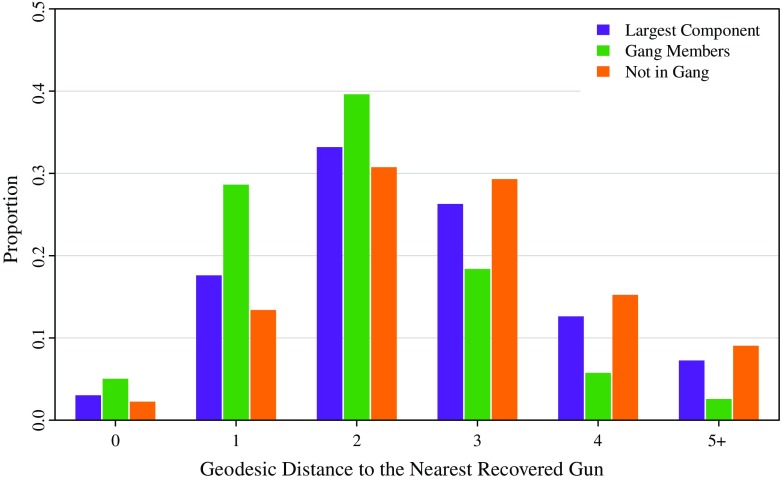

Table 1 also provides information on the distance to a recovered gun; supplemental material provides additional measures disaggregated by further demographic information (see, Supplemental Materials). On average, the shortest distance of any individual in the LCC to a recovered gun is 2.5 suggesting that, on average, any individual in the LCC is less than 3 co-offending handshakes away from a recovered firearm. In the context of Chicago’s illegal gun markets, this means that guns are in relatively close—but not necessarily immediate—access to individuals in the network. A distance of 2 equates with an “associates’ associate”—the equivalent of asking someone for a gun and that person replying, “I know someone who can get me a gun.” Gang membership reduces the distance to the closest firearm by about 27%. Figure 2 graphically depicts these distances disaggregated by gang membership. The increased “closeness” of gang members to guns relative to non-gang members in the network suggests that gangs facilitate individual access to firearms directly and indirectly.

Fig. 2.

Geodesic distance to the nearest recovered gun in the network by gang status

Those individuals closest to a recovered gun are gunshot victims themselves: on average, gun victims in the LCC are 1.8 co-offending ties away from a gun where as non-victims are 2.6 ties away from a recovered gun. Gang member victims are even closer at 1.6 co-offending ties from a recovered gun, as compared to non-gang victims who are 2.1 ties from a recovered gun.

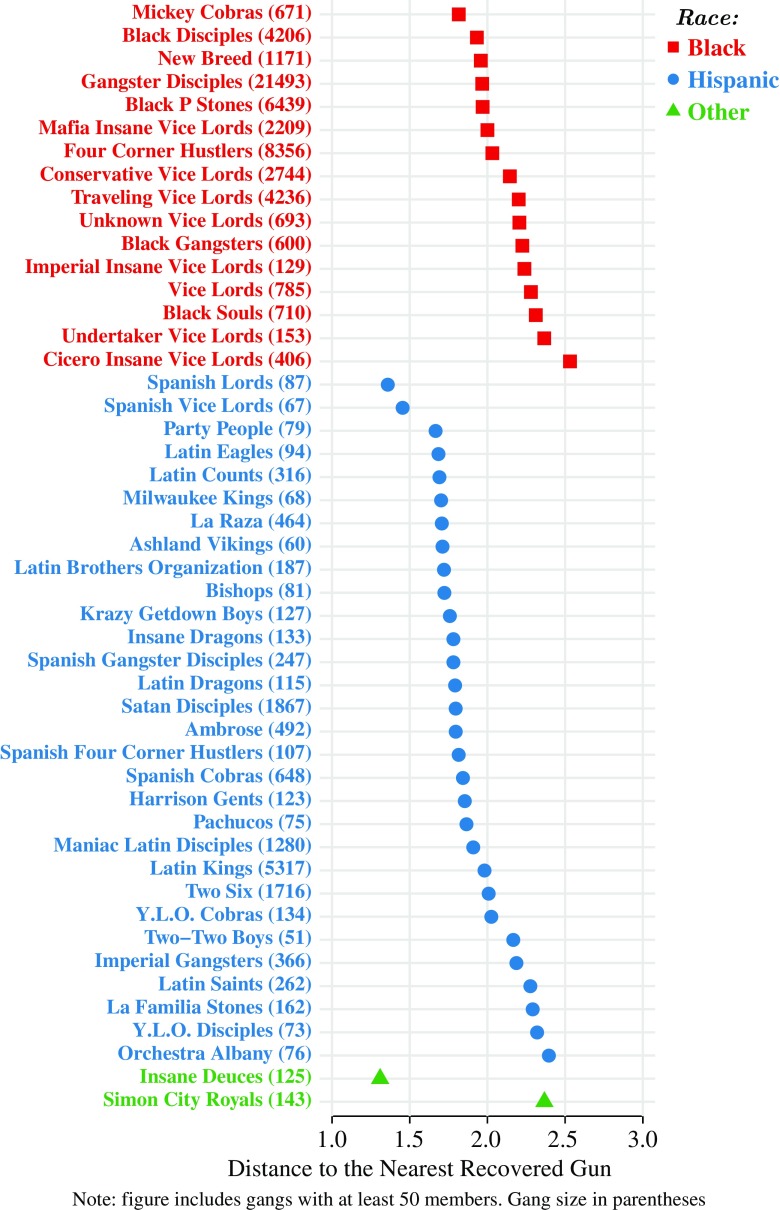

The descriptive statistics suggest that individuals in the network are less than 3 co-offending ties to a firearm and, importantly, that gangs seem to cut this distance considerably. To examine gang-level variation, Fig. 3 displays a visual interaction between the race and ethnic composition of 53 gangs in the LCC with at least 20 members and distance to guns. On average, Hispanic white gangs are closer to guns than non-Hispanic black gangs, although there is quite a bit of gang-level variation.

Fig. 3.

Geodesic distance to the nearest recovered gun in the network by gang

The black gangs listed in Fig. 3 more accurately represent gang “federations” or “nations” dating back to the 1960s that are less a single unified entity as a conglomerate of smaller related sets or crews [36–39]. The Gangster Disciples, for instance, is a larger umbrella identity that encompasses dozens of smaller factions. The same is true of the other black gangs listed in Fig. 3 including the Black P. Stones and the various Vice Lord groups [38, 40]. Thus, while it may appear that there are fewer black gangs relative to Hispanic gangs, this federation structure masks the number of total black groups and might also represent a greater organizational capacity. In contrast, the majority of Hispanic gangs—with the exception of the Latin Kings—tend to be smaller in size and more limited in organization structure. Whereas black gangs in Chicago actively sought to create city-wide networks and relationships both in the 1960s and again in the 1990s, Hispanic gangs in Chicago lacked a comparable period of conglomeration and were less overtly involved in developing city-wide federations [41].

Our descriptive findings suggest that such qualitative and historical differences in Chicago gangs may translate into the types of underlying networks of these groups and, by extension, influence gang members’ access to guns. The larger black gang federations might create longer distances and more dense networks through which firearms might have to travel—i.e., while an individual might have greater number of guns in his network, he might have to jump through additional associates or cliques to access them. In contrast, the smaller Hispanic gang networks might ensure more efficient monitoring of guns among a smaller number of members. This would translate into quicker access to firearms as there are fewer associates through which one would have to navigate to gain access.

Predicting Gunshot Victimization

Table 2 displays the results from four regression models. Model (1) presents our basic model and demonstrates that gang members that are closer to guns have a statistically significant greater probability of victimization. Specifically, the distance to nearest gun measure suggests that increasing the distance to the nearest gun by 1 co-offending tie decreases the probability of a gang member’s victimization by 0.05. Put another way, among gang members who have access to guns through their immediate associates, we would expect about 20% of them to be gunshot victims. Instead, if members have access through their associates’ associates (2 co-arrest ties removed), we would expect about 15% to be gunshot victims. In support of our basic hypothesis, greater access equates with greater levels of victimization among gang members.

Table 2.

Models predicting gunshot victimization among gang members

| Dependent variable: predicted probability of gunshot victimization | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Constant | 0.25*** | 0.24*** | 0.23*** | 0.26*** |

| (0.004) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | |

| Geodesic distance to nearest recovered gun | − 0.05*** | − 0.05*** | − 0.05*** | − 0.05*** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Black gang | 0.02*** | 0.002 | − 0.03*** | |

| (0.004) | (0.01) | (0.01) | ||

| Size of gang (in thousands) | 0.001*** | − 0.01*** | ||

| (0.0002) | (0.002) | |||

| Interaction of black gang and gang size | 0.01*** | |||

| (0.002) | ||||

| Observations | 34,106 | 34,106 | 34,106 | 34,106 |

*p < 0.1

**p < 0.05

***p < 0.01

Model (2) includes a control for membership in a black gang. The parameter is positive and statistically significant (p < 0.01): members of black gangs have a higher predicted probability of gunshot victimization, net of the effect of distance to a gun. Model (3) adds a control for gang size which is positive and statistically significant: members of larger gangs have a higher predicted probability of gunshot victimization, net of other factors. The distance to nearest gun measure remains significant in both models (2) and (3), indicating that the observed relationship remains: gang members that are closest to guns have higher rates of gun victimization.

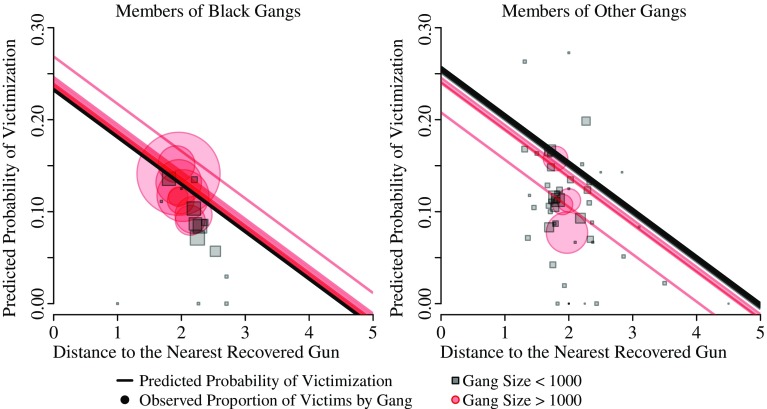

Model (4) adds an interaction term between gang size and the black gang dummy variable. This interaction term is also statistically significant (p < 0.01) and there is little fluctuation in the other parameters. Figure 4 visually represents this relationship by plotting the predicted probabilities and observed values based on model (4) with distance to guns on the horizontal axis and the probability of gunshot victimization on the vertical axis. Both graphs in Fig. 4 underscore the central finding that individuals closer to guns have greater likelihood of victimization. However, this relationship is especially pronounced for members of larger black gangs and smaller Hispanic gangs. As gang members’ distance to a gun decreases, their probability of gunshot victimization increases by 0.05, net of other factors. Taken together, the results consistently show that gang members who are closer to guns have a higher probability of gunshot victimization.

Fig. 4.

Relationship between distance to the nearest recovered gun and probability of gunshot victimization for gang members based on model (4). Predicted probabilities are estimated with the observed gang size values for members of black gangs and all other gangs. The symbol size is proportional to the gang size

Conclusion

Very few individuals in this country are denied the right to own a firearm. But one of those categories of prohibited individuals—those with a felony conviction—is a group that is at some of the highest levels of risk for gun homicide and assault. Despite such a prohibition, living in high-risk communities and networks continues to fuel the perception of needing a firearm, if only for self-protection. Illegal gun markets and personal networks offer methods for obtaining a firearm for such prohibited individuals. And, for many, street gangs and gang membership offer one such avenue for access to a firearm.

This study set out to quantify exactly how close offenders in Chicago were to an illegal firearm. Our analyses suggest that gang membership appears to facilitate access to guns, in part, by reducing the network distance to other individuals with a firearm by 20% or more. In particular gangs, the distance to a gun is even shorter suggesting that specific group dynamics may influence immediate access to firearms for individual gang members.

Our regression analyses confirmed that increased access to firearms impacts gunshot victimization among gang members: gang members with shorter distances to guns had corollary higher rates of victimization. Such access to guns also extended to indirect connections in the gang: among gang members with access to guns through their immediate associates, we would expect about 20% of members to be gunshot victims, a figure that declines to 15% for second-order access.

These findings suggest that gun violence reduction policy should be focused on reducing gang access to firearms in at least three ways. First, law enforcement agencies should identify and shut down direct supply lines of guns to gang members. Chicago gang members tend to acquire older guns through purchases from licensed dealers and secondary market sources in other states with weak gun laws [11]. If law enforcement is to be effective at reducing access to guns by gang members, it should focus on the intermediaries in the underground market—straw purchasers, brokers, and traffickers. Social network analyses, alongside further analyses of the purchasers of successfully traced firearms, could provide insight into the possible existence and functioning of these intermediaries.

Second, proximate access to guns should be reduced by identifying individuals in gang networks who hold illegal guns and those who could serve as brokers of guns. Network analyses that consider gun recoveries and shootings in gang networks could be used to good effect in guiding efforts to remove guns from Chicago streets, including through non-law enforcement agencies and public health outreach workers. Enforcement as well as related outreach and intervention efforts guided by network analyses of key actors could cause gang leaders to exert more control over their stash of guns and further restrict their distribution and use by members. In turn, diminished access by gang members could reduce shootings on Chicago streets.

Third, the sorts of risk estimates and network analytics used to identify individuals at elevated risk for gunshot victimization might be used to direct public health interventions aimed at reducing the injuries and trauma associated with gun violence—especially among gang members and their associates [42–44]. Such methods might serve as a force multiplier for intervention and prevention efforts by directing them towards those in harm’s way or indirectly impacted by gun violence, for example, by directly trauma care specialists or violence interrupters into strategic locations in the network.

These data are not without limitations. First, we use data from a single city and our findings may not be generalizable to other cities. Second, our measure of gun possession likely underestimates the true prevalence of guns in the hands of Chicago gang members and others in the observed co-offending network (see also Supplemental Materials). Moreover, these data do not provide any substantive information on the individuals holding guns in the co-offending networks and what their orientation towards facilitating broader access to firearms might be. Qualitative information collected through ethnography and community interviews are necessary to understand what role, if any, these individuals have in increasing gang access to firearms.

These limitations notwithstanding, approaching access to guns from a networked perspective provides unique insight into the prevention of gun violence and the operations of illegal gun markets. We believe that these data support the potential gun violence reduction benefits of disrupting supply lines of guns into criminal networks and focusing enforcement to reduce proximate access to guns by limiting their general prevalence in gang networks. Both avenues could increase the amount of time and effort to access guns by gang members and thereby decrease the prevalence of guns in these high-risk co-offending networks.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 1035 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank our fellow collaborators on the Multi-City Underground Gun Market Study and the University of Chicago Crime Lab for their comments and support of this project. Parts of this research were funded by grants to the corresponding author including a CAREER award (SES-1151449) from the Sociology, and Law and Social Science Programs at the National Science Foundation. This research was also supported in part by the facilities and staff of the Yale University Faculty of Arts and Sciences High Performance Computing Center, and a James S. McDonnell Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship Award in Studying Complex Systems awarded to the first author. The findings of this article represent the opinions of the authors and not those of the City of Chicago or the Chicago Police Department.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

All data and protocols for this project were approved by appropriate IRB.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth Roberto, Email: elizabeth.roberto@gmail.com.

Anthony A. Braga, Email: a.braga@northeastern.edu

Andrew V. Papachristos, Email: avp@northwestern.edu

References

- 1.Braga AA, Cook PJ. The criminal records of gun offenders. Georgetown J Law and Publ Policy. 2016;14(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGonigal MD, Cole J, Schwab CW, Kauder DR, Rotondo MF, Angood PB. Urban firearm deaths: a five-year perspective. Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 1993;35(4):532–536. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199310000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papachristos AV, Wildeman C, Roberto E. Tragic, but not random: the social contagion of nonfatal gunshot injuries. Social Sci Med. 2015;125(1):139–150. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braga AA. Serious youth gun offenders and the epidemic of youth violence in Boston. J Quant Criminol. 2003;19(1):33–54. doi: 10.1023/A:1022566628159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeoli AM, Grady SC, Pizarro JM, Melde C. Modeling the movement of homicide by type to inform public health prevention interventions. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(10):2035–2041. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weisburd DL, Bushway S, Lum C, Yang S-M. Trajectories of crime at places: a longitudinal study of street segments in the city of Seattle. Criminology. 2004;42(2):283–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2004.tb00521.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morenoff JD, Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW. Neighborhood inequality, collective efficacy, and the spatial dynamics of urban violence. Criminology. 2001;39(3):517–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2001.tb00932.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peterson RD, Krivo LJ. Divergent social worlds: neighborhood crime and the racial-spatial divide. New York, NY: Russell Sage; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green B, Horel T, Papachristos AV. Modeling contagion through social networks to explain and predict gunshot violence in Chicago, 2006 to 2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(3):326–333. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cook PJ, Ludwig J, Venkatesh SA, Braga AA. Underground gun markets. Econ J. 2007;117(1, 524):–588.

- 11.Cook PJ, Parker ST, Pollack HA. Sources of guns to dangerous people: what we learn by asking them. Prev Med. 2015;79(1):28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lizotte AJ, Tesoriero JM, Thornberry TP, Krohn MD. Patterns of adolescent firearms ownership and use. Justice Q. 1994;11(1):51–74. doi: 10.1080/07418829400092131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lizotte AJ, Bordua DJ, White CS. Firearms ownership for sport and protection: two not so divergent models. Am Sociol Rev. 1981;46(4):499–503. doi: 10.2307/2095271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thornberry TP, Krohn MD, Lizotte AJ, Smith CA, Tobin K. Gangs and delinquency in development perspective. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peterson D, Taylor TJ, Esbensen F-A. Gang membership and violent victimization. Justice Q. 2004;21(4):793–815. doi: 10.1080/07418820400095991. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warr M. Companions in crime: the social aspects of criminal conduct. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pyrooz DC, Moule RK, Jr, Decker SH. The contribution of gang membership to the victim–offender overlap. J Res Crime Delinq. 2014;51(3):315–348. doi: 10.1177/0022427813516128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papachristos AV, Braga AA, Piza E, Grossman L. The company you keep? The spillover effects of gang membership on individual gunshot victimization in social networks. Criminology. 2015;53(4):624–649. doi: 10.1111/1745-9125.12091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pyrooz DC. Uncovering the pathways between gang membership and violent victimization. J Quant Criminol. 2015;32(4):531–559. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bjerregaard B, Lizotte AJ. Gun ownership and gang membership. J Crim Law Criminol. 1995;86(1):37–58. doi: 10.2307/1143999. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braga AA, Wintemute GJ, Pierce GL, Cook PJ, Ridgeway G. Interpreting the empirical evidence on illegal gun market dynamics. J Urban Health. 2012;89(5):779–793. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9681-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papachristos AV, Hureau D, Braga AA. The corner and the crew: the influence of geography and social networks on gang violence. Am Sociol Rev. 2013;78(3):417–447. doi: 10.1177/0003122413486800. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tita GE, Radil SM. Spatializing the social networks of gangs to explore patterns of violence. J Quant Criminol. 2011;27(4):521–545. doi: 10.1007/s10940-011-9136-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klein MW, Maxson CL, Cunningham LC. Crack, street gangs, and violence. Criminology. 1991;29(4):623–650. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.1991.tb01082.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Block R, Block CR. Street gang crime in Chicago. In: Klein MW, Maxson CL, Miller J, editors. The Modern Gang Reader. Thousand Oaks, CA: Roxbury; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hureau D, Braga AA. The trade in tools: the market for illicit guns in high-risk networks. Criminology. 2018; 56 (3).

- 27.Cook PJ, Harris RJ, Ludwig J, Pollack HA. Some sources of crime guns in Chicago: dirty dealers, straw purchasers, and traffickers. J Crim Law and Criminol 2014:717–759.

- 28.Adamic L, Adar E. How to search a social network. Soc Networks. 2005;27(3):187–203. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2005.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howell N. The Search for an Abortionist. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wintemute GJ. The epidemology of firearm violence in the twenty-first century United States. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:5–19. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Decker SH, Katz CM, Webb VJ. Understanding the black box of gang organization: implications for involvement in violent crime, drug sales, and violent victimization. Crime and Delinquency. 2007;54(1):153–172. doi: 10.1177/0011128706296664. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Core Team R. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Csardi G, Nepusz T. The igraph software package for complex network research. Int J Complex Syst. 2006;1695(5):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kane MJ, Emerson JW, Weston S. Scalable strategies for computing with massive data. J Stat Softw. 2013;55(14):1–19. doi: 10.18637/jss.v055.i14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Revolution Analytics and Steve Weston. foreach: foreach looping construct for R. R package, CRAN.Rproject.org/package=foreach. 2014.

- 36.Levitt S, Venkatesh SA. An economic analysis of a drug-selling gang’s finances. Q J Econ. 2000;115(3):755–789. doi: 10.1162/003355300554908. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Venkatesh SA, Levitt SD. Are we a family or a business?; history and disjuncture in the urban American street gang. Theory and Society. 2000;29(4):427–462. doi: 10.1023/A:1007151703198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dawley D. A nation of lords; the autobiography of the Vice Lords. [1st ] ed. Garden City: N.Y., Anchor Press; 1973.

- 39.Perkins UE. Explosion of Chicago’s Black street gangs: 1900 to the present. 1st ed. Chicago, Ill.: Third World Press; 1987.

- 40.Moore NY, WIlliams L. The Almighty Black P Stone Nation: the Rise, Fall, and Resurgence of an American Gang. Chicago, IL: Lawrence Hill Books; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hagedorn JM. The In$ane Chicago Way: the Daring Play by Chicago Gangs to Create a Spanish Mafia. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Butts JA, Roman CG, Bostwick L, Porter JRP. Cure violence: a public health model to reduce gun violence. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:39–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hanson RF, Sawyer GK, Begle AM, Hubel GS. The impact of crime victimization on quality of life. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23(2):189–197. doi: 10.1002/jts.20508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee J. Wounded: life after the shooting. Ann Am Acad Pol Social Sci. 2012;642(1):244–257. doi: 10.1177/0002716212438208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kennedy DM, Piehl AM, Braga A. Youth violence in Boston: gun markets, serious youth offenders, and a use-reduction strategy. Law and Contemp Prob. 59(1):147–96.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 1035 kb)