Abstract

Introduction

Financial strain and discrimination are consistent predictors of negative health outcomes and maladaptive coping behaviors, including tobacco use. Although there is considerable information exploring stress and smoking, limited research has examined the relationship between patterns of stress domains and specific tobacco/nicotine product use. Even fewer studies have assessed ethnic variations in these relationships.

Methods

This study investigated the relationship between discrimination and financial strain and current tobacco/nicotine product use and explored the ethnic variation in these relationships among diverse sample of US adults (N = 1068). Separate logistic regression models assessed associations between stress domains and tobacco/nicotine product use, adjusting for covariates (e.g., age, gender, race/ethnicity, and household income). Due to statistically significant differences, the final set of models was stratified by race/ethnicity.

Results

Higher levels of discrimination were associated with higher odds of all three tobacco/nicotine product categories. Financial strain was positively associated with combustible tobacco and combined tobacco/nicotine product use. Financial strain was especially risky for Non-Hispanic Whites (AOR:1.191, 95%CI:1.083–1.309) and Blacks/African Americans (AOR:1.542, 95%CI:1.106–2.148), as compared to other groups, whereas discrimination was most detrimental for Asians/Pacific Islanders (AOR:3.827, 95%CI:1.832–7.997) and Hispanics/Latinas/Latinos (AOR:2.517, 95%CI:1.603–3.952).

Conclusions

Findings suggest discrimination and financial stressors are risk factors for use of multiple tobacco/nicotine products, highlighting the importance of prevention research that accounts for these stressors. Because ethnic groups may respond differently to stress/strain, prevention research needs to identify cultural values, beliefs, and coping strategies that can buffer the negative consequences of discrimination and financial stressors.

Keywords: Tobacco, Nicotine, Financial strain, Stress, Race, Ethnicity

Highlights

-

•

Increased discrimination is associated with higher odds of combustible and electronic tobacco/nicotine product use.

-

•

Higher financial strain is associated with higher odds of combustible and combined tobacco/nicotine product use.

-

•

Financial strain was especially risky for Non-Hispanic Whites and Blacks/African Americans, as compared to other groups.

-

•

Discrimination was most detrimental for Asians/Pacific Islanders and Hispanics/Latinas/Latinos, as compared to other groups.

-

•

Future research needs to identify cultural values and coping strategies that can buffer consequences of psychosocial stress.

1. Background

Although cigarette smoking has declined in the United States (US), smoking prevalence remains high in specific subpopulations and continues to be the country's leading cause of preventable disease and death (Jamal et al., 2016; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014). Moreover, smoking prevalence varies by demographic subgroups, including race/ethnicity, economic status, and stress status (Chen & Unger, 1999; DeCicca, Kenkel, & Mathios, 2000; Jamal et al., 2016; Unger et al., 2001). Persons living below the poverty level have twice the prevalence rates of smoking compared to persons living above the poverty level (26.1% to 13.9% respectively), and persons with serious psychological distress report dramatically higher prevalence of smoking (40.6%) compared to persons experiencing lower levels of stress (14.0%), with notable differences across ethnicity (Jamal et al., 2016). It is therefore important to identify ethnic differences in smoking risk factors and develop culturally tailored cessation approaches to augment current prevention efforts.

Psychosocial stressors, such as financial strain, discrimination, work stress, and adverse life events, are consistent predictors of substance use and negative health outcomes (Levi, 1974; Levine & Scotch, 2013; Thoits, 2010) as they strain an individual's internal resources and ability to effectively cope (Kamarck, 2012; Lazarus, 1966; Slopen et al., 2013). Chronic and acute stress elicit psychological and physiological responses that undermine self-regulation and overload coping strategies, increasing vulnerability for nicotine use (Conway, Vickers Jr, Ward, & Rahe, 1981; Landrine & Klonoff, 1996; Ng & Jeffery, 2003; Slopen et al., 2013). Because nicotine can reduce stressful feelings and provide short-term positive reinforcement (Conway et al., 1981; Koob & Le Moal, 2002; Ng & Jeffery, 2003; Parrott, 1995; Slopen et al., 2013), smoking is often a form of self-medication.

Discriminatory stress resulting from ethnic, sexual orientation, or gender discrimination predicts tobacco product use particularly among women and ethnic minority groups (Chae et al., 2008; Guthrie, Young, Williams, Boyd, & Kintner, 2002; Unger, 2018). Financial strain is also associated with smoking and is commonly defined as economic hardships such as financial anxiety due to debt, being unable to afford needed items, poor housing conditions, long-term unemployment, and low income (Guillaumier et al., 2017; Kahn & Pearlin, 2006; Siahpush, Borland, & Scollo, 2003; Siahpush & Carlin, 2006; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014). Although studies have shown that a degree of financial strain can promote a reduction in smoking, severe financial strain increases quitting difficulty and increases relapse after quitting (Guillaumier et al., 2017; Kendzor et al., 2010; Pyle, Haddock, Poston, Bray, & Williams, 2007; Siahpush, Yong, Borland, Reid, & Hammond, 2009). Since severe financial strain is negatively associated with cessation, and smoking rates are highest among economically vulnerable populations and those with low socioeconomic status (SES) (Kendzor et al., 2010; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014), prevention efforts need to focus on disadvantaged groups.

Discriminatory and financial stressors are not equally distributed across populations and tend to vary by ethnicity, with disparities in tobacco product use especially pronounced in populations dealing with ethnic discrimination, such as African Americans (Guthrie et al., 2002; Landrine & Klonoff, 2000; Slopen et al., 2012), Asians/Pacific Islanders (Booker et al., 2007; Forster, Grigsby, Rogers, & Benjamin, 2018), Hispanics (Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2011, Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2012), and multiethnic populations (Booker, Gallaher, Unger, Ritt-Olson, & Johnson, 2004; Unger et al., 2001). Although there is a wealth of information exploring individual stressors and cigarette use, limited research has explored the effects of multiple domains of stress and the use of several types of tobacco/nicotine products. Typically, studies have not examined whether there are ethnic variations in the relationship between patterns of stress domains that include discrimination and financial strain and tobacco/nicotine use (Slopen et al., 2012; Slopen et al., 2013). To fill this gap in the literature, the present study examined differences in the relationship between discrimination and financial strain, and tobacco/nicotine product use across four groups.

Since the proliferation of alternative nicotine delivery systems, trends indicate that a large portion of the tobacco market is shifting from traditional, combustible tobacco products to alternative nicotine delivery systems such as smokeless tobacco and electronic nicotine products (Alcalá, von Ehrenstein, & Tomiyama, 2016; Bhattacharyya, 2012; Nguyen et al., 2015). Although e-cigarettes contain fewer toxicants, this move from traditional cigarette smoking to other tobacco products does not necessarily eliminate all negative health outcomes (National Academies of Sciences, E., and Medicine, 2018). With the increase in the prevalence and popularity of novel nicotine/tobacco products, it is important to explore possible ethnic variations in the relationship between discrimination and financial stress and combustible and electronic tobacco/nicotine product use.

The present study assessed the possible dose-response relationship between discrimination and financial strain, and current tobacco/nicotine product use. We hypothesized that financial stressors would be associated with higher odds of current H1) combustible tobacco product use; H2) electronic nicotine product use; and H3) any tobacco/nicotine product use. We also hypothesized that discrimination would be associated with higher odds of current H4) combustible tobacco product use; H5) electronic nicotine product use; and H6) any tobacco/nicotine product use. We also explored racial/ethnic differences in these associations; however, due to limited prior research in this area, we did not develop a priori hypotheses about the strength or direction of racial/ethnic differences.

2. Methods

Participants (N = 1068) were recruited through Mechanical Turk (MTurk), a website facilitated by Amazon that crowdsources participants, matching “workers” with available tasks from “requesters” (Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, 2011; Sheehan, 2017). With demographics similar to the general US population and a successful track record with tobacco product use studies, MTurk allows researchers' access to a large population of willing and diverse research participants (Buhrmester et al., 2011; mTURK Tracker, 2017; Sheehan, 2017; Snider, Cummings, & Bickel, 2017; Unger, 2018). Data collected represent participants residing in 44 different states with the largest proportion of respondents living in California (11%), Florida (7.4%), New York (7.0%), and Texas (6.7%).

Inclusion criteria were US residency, being at least 18 years old, and having at least 90% of previous MTurk assignments completed. Consenting participants completed an electronic 30-item survey approved by the University of Southern California Institutional Review Board. The questionnaire took approximately 20 min to complete and included questions about demographics, SES and financial strain, tobacco/nicotine product use, social stress and discrimination, and social support and adverse childhood experiences. Participants received a $5 compensation upon completion, through the MTurk system.

3. Measures

3.1. Financial strain

The index measuring accumulated financial strain was comprised of items from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, Children and Adults, and items were prefaced with, “During the past 12 months” (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2017). Difficulty paying bills was one item asking: “How much difficulty have you had paying bills?” Responses were dichotomized to “No difficulty” to “Some difficulty” = 0 or “Quite a bit of difficulty” to “Great difficulty” = 1. Not making “ends meet” each month was assessed by asking: “Thinking about the end of each month, did you generally end up with…” Responses were dichotomized to “More than enough” to “Just enough” = 0 or “Not enough” = 1. Putting off buying needed items was measured by asking: “How often do you put off buying something you need such as food, clothing, medical care, or housing because you don't have money?” Response options were dichotomized to “Never” and “Rarely” = 0 or “Occasionally” and “All the time” = 1. Emergency fund was measured by asking: “Have you set aside emergency or rainy-day funds that would cover your expenses for three months in case of sickness, job loss, economic downturn, or other emergencies?” Selection options were “Yes” = 1 and “No” = 0. Consequences of financial delinquency were comprised of: “Had an account sent to a collection agency,” “Had something repossessed,” “Filed for bankruptcy,” and “Foreclosure of a property you owned or were renting.” Response options were coded “No” to all four items = 0 or “Yes” to any of the four items = 1. Needing a payday loan was measured by asking: “Received a loan from a payday or other store-front lender.” Selection options were “Yes” = 1 and “No” = 0. Overdue bills (>60 days) were comprised of three items: “Utility bills,” “Credit card bills,” and “Other bills.” Selection options were coded: “Not late to any bills” = 0 or “Late to at least one of the three bills” = 1. Overdue loans (>60 days) were comprised of: “Mortgage or rent,” “Car payment,” and “Other kinds of loans.” Selection options were coded: “Not late to any loans” = 0 or “Late to at least one loan” = 1. A cumulative financial strain index score was calculated by summing affirmative responses ranging from 0 to 8.

3.2. Discrimination

Discrimination related distress can occur as a result of discrimination based on many characteristics: gender, race, age, physical appearance, income/education, and weight. Discrimination was measured with the Everyday Discrimination Scale (Williams, Yu, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997). Sample items include: “Treated with less courtesy than others,” “Treated with less respect than others,” “Receive poorer service than others,” “People act as if they think you are not smart,” “People act as if they are afraid of you,” “People act as if they think you are dishonest,” and “People act as if they're better than you are” (Essed, 1991b; Williams et al., 1997). Response options ranged from 0 “Never” to 5 “Almost every day.” Responses were summed (Cronbach's alpha 0.938) and standardized with a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1.

3.3. Covariates

Gender/Sex was coded female = 1 and male = 0. Race/ethnicity was comprised of Black/African American, Native American, Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic/Latina/o, and multiracial/other, with Non-Hispanic White as the reference group. Due to low numbers, “Native American” and “Multiracial/Other” were excluded from models. Age was categorical and comprised of response options; “17 or younger,” “18–20,” “21–29,” “30–39,” “40–49,” “50–59,” and “60 or older.” Due to low numbers, age was truncated to; “29 or younger,” “30–39,” “40–49,” and “50 or older.”

3.4. Combustible tobacco product use

Combustible tobacco product use was measured by assessing how often the respondents used “cigarettes,” “cigar,” “tobacco in a pipe,” and “hookah.” Responses were summed and then dichotomized to: do not use = 0 and use = 1.

3.5. Electronic nicotine product use

Nicotine product use was measured by assessing how often the respondents use “electronic cigarettes/e-cigarettes/vaping” and “heat-not-burn product such as iQOS.” Responses were summed and then dichotomized to: do not use = 0 and use = 1.

3.6. Any tobacco/nicotine product use

Tobacco/nicotine product use was measured by assessing how often the respondents use “cigarettes,” “electronic cigarettes/e-cigarettes/vaping,” “cigar,” “tobacco in a pipe,” “hookah,” “smokeless/chewing tobacco,” and “heat-not-burn product such as iQOS.” Responses were summed and then dichotomized to: do not use = 0 and use = 1.

4. Analysis

To assess potential dose-response relationships, three separate logistic regression models assessed the associations between financial strain and discrimination and combustible tobacco product use, electronic nicotine product use, and any tobacco/nicotine product use; adjusting for covariates (e.g., age, gender, ethnicity and, household income). Interaction terms were calculated to determine whether these associations differed across ethnicity. Due to statistically significant ethnic variation in these associations, the final set of models was stratified. Stratified logistic regression analyses tested the associations between financial strain and discrimination with combustible tobacco product use, electronic nicotine product use, and any tobacco/nicotine product use; adjusting for covariates. Probabilities of combustible and electronic tobacco/nicotine product use by stress domain and ethnicity were calculated using the delta method. Analyses were conducted using SPSS software version 24, with statistical significance level set to 0.05 (IBM Corp, 2016).

5. Results

Slightly over half of respondents identified as male (58.8%) and reported having a household income below $50,000 (53.8%). The most frequently reported age range was 29 years and younger (40.6%) (Table 1). Much of the sample identified as Non-Hispanic White (67.0%) and the average everyday discrimination score was 8.698 (SD = 7.303) (Table 1). Approximately two-thirds of the sample reported at least one financial stressor (69.8%), with an average of 1.837 (SD = 1.854) financial stressors; yet among those reporting any financial stressors, the average was 2.513 (SD = 1.533). Overall, 47.4% of the sample reported using tobacco products; with 40.7% using combustible tobacco products; 25.6% using electronic nicotine products; and 4.3% using smokeless/chew tobacco products (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the 2016 MTURK Survey (N = 1070).

| Variables | % (n) | Variables | % (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | Financial strain | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 67.0% (701) | 0 Stressors | 30.2% (319) |

| Black/African American | 10.2% (107) | 1 Stressors | 22.8% (241) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 9.3% (97) | 2 Stressors | 18.6% (197) |

| Hispanic/Latina/Latino | 11.7% (122) | 3 Stressors | 9.5% (101) |

| Multiracial/Other | 1.8% (19) | 4 Stressors | 7.3% (77) |

| 5 Stressors | 6.0% (64) | ||

| Gender | 6 Stressors | 3.9% (41) | |

| Female | 40.1% (430) | 7 Stressors | 1.2% (13) |

| Male | 58.8% (630) | 8 Stressors | 0.5% (5) |

| Do you use any tobacco products? | |||

| Age | No | 52.6%(558) | |

| 29 or younger | 40.6%% (435) | Yes | 47.4% (503) |

| 30–39 | 37.2% (397) | Do you use electronic nicotine products? | |

| 40–49 | 12.6% (134) | No | 74.4%(796) |

| 50 or older | 9.4% (101) | Yes | 25.6% (274) |

| Do you use combustible tobacco products? | |||

| Household income | No | 59.3%(635) | |

| Below $50,000 | 53.8% (576) | Yes | 40.7%% (435) |

| $50,000 and above | 45.6% (482) | Variables | Mean (SD) |

| Unstandardized discrimination score | 8.698 (7.303) | ||

SD = Standard Deviation.

Regarding the first aim, there was a significant dose-response relationship between both domains of stress and each tobacco/nicotine product type apart from the relationship between financial strain and electronic nicotine product use. Financial strain was associated with higher odds of both combustible tobacco product use (AOR:1.205 95%CI:1.111–1.306) and any tobacco/nicotine product use (AOR:1.139 95%CI:1.050–1.234), but was not associated with electronic nicotine product use. Discrimination was associated with an increase in the odds of all types of tobacco/nicotine product use: combustible (AOR:1.448, 95%CI:1.253–1.672), electronic (AOR:1.444, 95%CI:1.241–1.697), and any tobacco/nicotine product use (AOR:1.424, 95%CI:1.233–1.644) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Direct effects and interactions between stressors and tobacco/nicotine product use.

| Combustible Tobacco Product Use | Electronic Nicotine | ALL Tobacco/Nicotine (Combustible, Electronic, and Smokeless) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effects | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | |

| Discrimination | 1.448*** | (1.253–1.672) | 1.444*** | (1.241–1.697) | 1.424*** | (1.233–1.644) | |

| Financial Strain | 1.205*** | (1.111–1.306) | 1.072 | (0.984–1.168) | 1.139** | (1.050–1.234) | |

| Interactions | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | |

| Financial Strain | Black | 1.180 | (0.893–1.558) | 1.161 | (0.888–1.518) | 1.250 | (0.944–1.654) |

| API | 0.718* | (0.529–0.975) | 0.542* | (0.330–0.892) | 0.732* | (0.540–0.992) | |

| Hispanic | 0.801 | (0.638–1.007) | 0.808 | (0.637–1.024) | 0.823 | (0.657–1.031) | |

| Discrimination | Black | 1.763* | (1.079–2.880) | 1.271 | (0.794–2.034) | 1.928* | (1.172–3.173) |

| API | 2.128* | (1.125–4.025) | 1.732 | (0.950–3.155) | 2.361* | (1.230–4.533) | |

| Hispanic | 1.707* | (1.105–2.635) | 1.561* | (1.020–2.388) | 1.687* | (1.105–2.574) | |

Note: Direct effect models control for age, gender, ethnicity, household income, and other stressors.

Note: Non-Hispanic Whites are not represented in the table because they are the reference group.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, AOR = Adjusted Odds Ratio, 95% CI = 95% Confidence Interval.

Black = African American/Black, API = Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic = Hispanic/Latina/Latino.

Regarding the second aim, there was significant variability in relationships between domains of stressors and tobacco/nicotine product use across ethnic groups. Among Non-Hispanic Whites, every additional financial stressor was associated with an increase in the odds of combustible tobacco product use (AOR:1.265, 95%CI:1.151–1.391), electronic nicotine product use (AOR:1.127, 95%CI:1.020–1.245), and any tobacco/nicotine product use (combustible, electronic, and smokeless/chew) (AOR:1.191, 95%CI:1.083–1.309). Similarly, financial strain was associated with an increase in the odds of using all types of tobacco/nicotine products: combustible (AOR:1.592, 95%CI:1.142–2.221), electronic (AOR:1.437, 95%CI:1.056–1.956), and any tobacco/nicotine product use (AOR:1.542, 95%CI:1.106–2.148) among Blacks/African Americans. However, among Asians/Pacific Islanders, financial strain was not associated with combustible tobacco product use or any tobacco/nicotine product use and was associated with a decrease in the odds of electronic nicotine product use (AOR:0.501, 95%CI:0.260–0.965). Among Hispanics/Latinas/os, there was no association between financial strain and any of the categories of tobacco/nicotine product use (Table 3).

Table 3.

Associations between stressors and tobacco/nicotine product use stratified by ethnicity.

| Combustible tobacco |

Electronic nicotine |

ALL tobacco/nicotine (Combustible, electronic, and smokeless) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strata | Variables | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI |

| White | Discrimination | 1.174 | (0.988–1.395) | 1.225* | (1.018–1.474) | 1.137 | (0.959–1.350) |

| Financial strain | 1.265*** | (1.151–1.391) | 1.127* | (1.020–1.245) | 1.191*** | (1.083–1.309) | |

| Black | Discrimination | 1.972* | (1.171–3.319) | 1.429 | (0.865–2.358) | 2.070** | (1.222–3.507) |

| Financial strain | 1.592** | (1.142–2.221) | 1.437* | (1.056–1.956) | 1.542* | (1.106–2.148) | |

| API | Discrimination | 3.128** | (1.572–6.224) | 3.658** | (1.738–7.700) | 3.827** | (1.832–7.997) |

| Financial strain | 0.807 | (0.536–1.216) | 0.501* | (0.260–0.965) | 0.759 | (0.496–1.161) | |

| Hispanic | Discrimination | 2.808*** | (1.737–4.541) | 2.580*** | (1.613–4.128) | 2.517*** | (1.603–3.952) |

| Financial strain | 0.897 | (0.687–1.171) | 0.798 | (0.605–1.053) | 0.867 | (0.669–1.124) | |

Note: All models control for age, gender, household income, and other stressors.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.001, OR = Odds Ratio, 95% CI = 95% Confidence Interval, FS = Financial Strain, SS = Social Stress.

There were also ethnic differences in the discrimination and tobacco/nicotine use relationship. Among Non-Hispanic Whites, higher discrimination scores were associated with an estimated increase in the odds of electronic nicotine product use (AOR:1.255, 95%CI:1.018–1.474); however, after controlling for financial stress and other covariates, discrimination was not associated with other categories of tobacco/nicotine product use. Conversely, among Blacks/African Americans, discrimination was associated with higher odds of combustible tobacco product use (AOR: 1.972, 95%CI:1.171–3.319) and any tobacco/nicotine product use (AOR: 2.070, 95%CI:1.222–3.507), but not for electronic nicotine product use. Among Asians/Pacific Islanders, discrimination was also associated with higher odds of all types of tobacco/nicotine product use: combustible (AOR: 3.128, 95%CI:1.572–6.224), electronic (OR: 3.658, 95%CI: 1.738–7.700), and any tobacco/nicotine product use (AOR:3.827, 95%CI:1.832–7.997). Among Hispanics/Latinas/os, discrimination was associated with higher odds of all types of tobacco/nicotine product use: combustible (AOR:2.808, 95%CI:1.737–4.541), electronic (AOR: 2.580, 95%CI:1.613–4.128), and any tobacco/nicotine product use (AOR: 2.517, 95%CI:1.603–3.952) (Table 3).

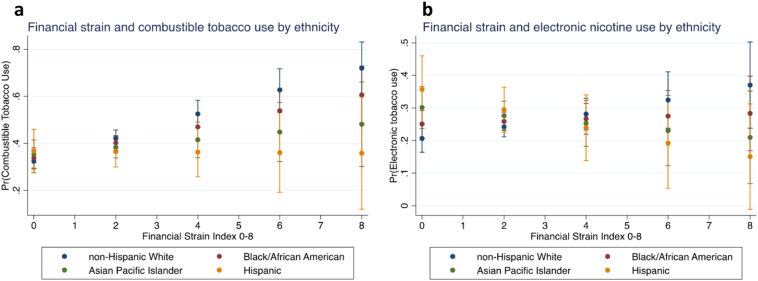

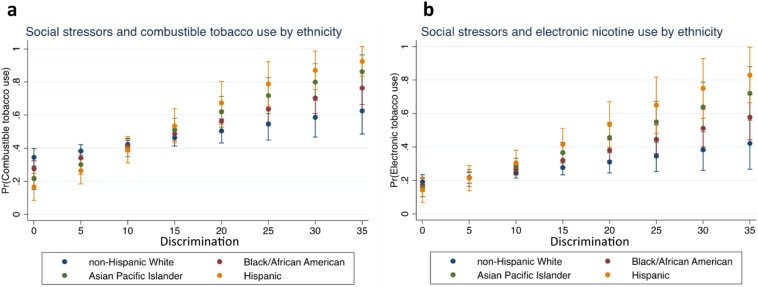

There were pronounced differences in the probabilities of tobacco/nicotine product by ethnicity among respondents with higher scores on both stress domains. At higher levels of financial strain, the probabilities of Hispanics/Latinas/os using either combustible or electronic tobacco/nicotine products were higher as compared to other ethnic groups. This contrasts with Non-Hispanic Whites who increased from the lowest probabilities among all reported ethnicities, to the highest probabilities at the higher levels of financial strain (Fig. 1a & b). Higher discrimination was associated with higher probabilities of tobacco/nicotine product use for all ethnicities; however, Hispanics/Latinas/os have the sharpest increase followed by Asians/Pacific Islanders, and Blacks/African Americans (Fig. 2a & b).

Fig. 1.

a & b Probabilities of tobacco/nicotine product use by financial strain and ethnicity.

Fig. 2.

a & b Probabilities of tobacco/nicotine product use by discrimination and ethnicity.

6. Discussion

The current study investigated the relationship between discrimination, financial strain, and three categories of tobacco/nicotine product use. Nearly half of the sample reported using tobacco/nicotine products, well above the national average. Moreover, slightly over half of respondents fell below the median US household income level (Guzman, 2017). These findings are in accordance with studies demonstrating a higher prevalence of tobacco/nicotine product use among lower income households (Guillaumier et al., 2017; Jamal et al., 2016; Siahpush & Carlin, 2006). In fact, tobacco/nicotine product use may contribute to exacerbation of financial hardships and increasing stress (Siahpush et al., 2003; Slopen et al., 2013) due to cost and stigma of using tobacco/nicotine products. Our results also comport with research suggesting that financial strain and social stress, including discrimination, increase risk of smoking (Guillaumier et al., 2017; Guthrie et al., 2002; Siahpush et al., 2003; Slopen et al., 2013), and contribute to the literature by exploring these relationships across combustible and electronic tobacco/nicotine products. Ethnic differences were significant even after adjusting for demographics and household income, suggesting both domains of stress are uniquely associated with an increased risk of tobacco/nicotine product use beyond SES. Although, it is worth noting that overall, African American respondents reported significantly higher discrimination scores, potentially exacerbating the relationships found. These patterns are not unique; they have been seen in other studies and may in part be due to some items from the Everyday Discrimination Scale being adopted from qualitative work in African American populations (Essed, 1991a, Essed, 1991b; Kim, Sellbom, & Ford, 2014). However, this does not detract from the overall findings or those within other ethnic groups. Moreover, this makes an even stronger case for considering the benefits that culturally tailored intervention could have, given the significant differences across stress domains.

Although accumulated stress was not tested in this research, it is key that stress models consider the joint effects of multiple types of stressors and tobacco/nicotine product use. Tobacco/nicotine prevention strategies may benefit from programs that explicitly link discrimination and financial strain to culturally-based coping and social support. In sum, these findings build on research suggesting that future work will need to identify whether cultural factors associated with lower odds of risky behaviors can mitigate the negative effects of discriminatory and financial stressors for nicotine use (Forster, Grigsby, Soto, Sussman, & Unger, 2017; Soto et al., 2011; Unger et al., 2002; Unger, Shakib, Gallaher, & Ritt-Olson, 2006).

Although no causal inference can be drawn from cross-sectional research, these data suggest that the risks associated with stressors for tobacco/nicotine product use differ across product type. Research has demonstrated discrimination and financial strain as strong predictors of tobacco/nicotine product use; however, in the present study, discrimination was a risk factor for all tobacco/nicotine products, whereas financial strain was not associated with electronic product use. This may be due in part to marketing practices of nicotine product companies and the initial startup costs of electronic nicotine products compared to a pack of cigarettes. There may be unique patterns of stress/strain associated with use of specific tobacco/nicotine products and future studies may benefit from analysis of these patterns to determine if these relationships hold in the general population and if patterns are linked to individual tobacco/nicotine products. Although preliminary, we also identified potential ethnic variation in the relationship between increased stress and tobacco/nicotine product use, building on previous work investigating these variations in stress and tobacco/nicotine use. Our findings contribute to the growing, but limited literature, of patterns of variation across a broad range of ethnic backgrounds. Among this sample, discrimination was associated with an increase in the odds of tobacco/nicotine product use among minority populations; however, financial strain was a risk factor among Non-Hispanic Whites and Blacks/African Americans, and discrimination was significantly riskier among Asians/Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics/Latinas/os for all three categories of tobacco/nicotine product use, when compared to all other ethnic backgrounds. This pattern of results suggests that tobacco/nicotine interventions designed for these populations need to consider strategies that mitigate specific stressors, including discrimination. Due to the limited sample size, these findings are preliminary; however, when considering prior research, it suggests that there is an underlying relationship that needs to be further explored in future studies using diverse samples. Understanding that different ethnic populations have varying experiences with stress, these unique patterns provide further evidence for the utility of ethnically tailored tobacco/nicotine product use intervention and the inclusion of specific stress coping strategies, depending on ethnic background. Moreover, when considering both intervention and policy initiatives, it is important to note that stress plays a unique role in the use of different tobacco/nicotine products. This information provides insight into determining possible cessation strategies for specific tobacco/nicotine products.

There is a growing body of research suggesting psychosocial stressors, including discrimination and financial strain, play a key role in all types of tobacco/nicotine product use, underscoring the importance of considering psychosocial stress in smoking prevention strategies. Macro-policy considerations may serve to reduce chronic hardships and inequalities while intervention may improve by leveraging downstream mediators. Future studies should consider possible culture specific moderators in the relationship between stressors and different types of tobacco/nicotine product use to inform intervention and policies so that they can leverage cultural factors and develop tailored prevention and recovery strategies for disadvantaged, high-risk populations.

6.1. Limitations

There are several limitations to the current study. First, due to self-selection, this study is similar to other convenience samples with limited generalizability. Though MTurk data is not representative of any specific population, the demographics of the current sample are relatively similar to that of the US population; although, MTurk samples tend to be more diverse than samples typically used in clinical research (Chandler & Shapiro, 2016). Nevertheless, studies suggest that MTurk data produces highly reliable scale data and is well-studied with nearly 15,000 papers using the MTurk platform as a data collection resource. Although data came from 44 states, due to the sample size, regional differences were not examined, but should be a focus area of future studies. Second, any inferences should be considered in light of the cross-sectional design of the study that cannot establish causal relationships or temporal ordering. Third, although the sample was large enough to analyze patterns among aggregate categories of tobacco/nicotine product use, future research, using larger samples, needs to explore these associations across a broad variety of products (e.g., chew, hookah, e-cigarette, etc.). Fourth, because of limited variability, demographic categories were truncated, and ethnicity was divided into four categories. More work is needed to replicate these relationships in large, multiethnic samples. Fifth, prior work has shown that although the Everyday Discrimination Scale has an overall measurement equivalence across racial/ethnic groups, when using the seven item scale, Asian and Hispanic populations tended to score lower on latent constructs as compared to Non-Hispanic White and African American populations (Kim et al., 2014). In this study, African Americans did have significantly higher discrimination scores compared to all other race/ethnicities, and racial/ethnic differences should be considered in light of these potential measurement inequalities. Sixth, future study should consider additional tobacco/nicotine products such as cigarillos and smokeless tobacco. Although smokeless tobacco was included in the study, the limited response did not allow this product to be analyzed. Both cigarillos and smokeless tobacco have unique ethnic associations, and as such, are an important part of understanding ethnic difference in any tobacco/nicotine product research.

6.2. Conclusion

Discrimination and financial strain are risk factors for use of multiple tobacco/nicotine products, highlighting the importance of policy and prevention research that accounts for psychosocial stress in tobacco control initiatives. Because stress/strain exposure is not equally distributed in the population and subsets of the population may respond differently to specific domains of stress, future prevention research needs to identify cultural values, beliefs, and coping strategies that can buffer the negative consequences of discrimination and financial strain.

Declarations of interest

None.

References

- Alcalá H.E., von Ehrenstein O.S., Tomiyama A.J. Adverse childhood experiences and use of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco products. Journal of Community Health. 2016;41(5):969–976. doi: 10.1007/s10900-016-0179-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya N. Trends in the use of smokeless tobacco in United States, 2000–2010. The Laryngoscope. 2012;122(10):2175–2178. doi: 10.1002/lary.23448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booker C., Gallaher P., Unger J., Ritt-Olson A., Johnson A. Stressful life events, smoking behavior, and intentions to smoke among a multiethnic sample of sixth graders. Ethnicity and Health. 2004;9(4):369–397. doi: 10.1080/1355785042000285384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booker C.L., Unger J.B., Azen S.P., Baezconde-Garbanati L., Lickel B., Johnson C.A. Stressful life events and smoking behaviors in Chinese adolescents: A longitudinal analysis. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9(11):1085–1094. doi: 10.1080/14622200701491180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester M., Kwang T., Gosling S.D. Amazon's Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2011;6(1):3–5. doi: 10.1177/1745691610393980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics National longitudinal survey of youth children and adults. 2017. https://www.nlsinfo.org/content/cohorts/nlsy79-children/topical-guide/income/financial-strain Retrieved from.

- Chae D.H., Takeuchi D.T., Barbeau E.M., Bennett G.G., Lindsey J., Krieger N. Unfair treatment, racial/ethnic discrimination, ethnic identification, and smoking among Asian Americans in the National Latino and Asian American Study. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(3):485–492. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.102012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler J., Shapiro D. Conducting clinical research using crowdsourced convenience samples. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2016;12 doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Unger J.B. Hazards of smoking initiation among Asian American and non-Asian adolescents in California: A survival model analysis. Preventive Medicine. 1999;28(6):589–599. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway T.L., Vickers R.R., Jr., Ward H.W., Rahe R.H. Occupational stress and variation in cigarette, coffee, and alcohol consumption. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1981:155–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCicca P., Kenkel D., Mathios A. Racial difference in the determinants of smoking onset. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 2000;21(2):311–340. [Google Scholar]

- Essed P. Knowledge and resistance: Black women talk about racism in the Netherlands and the USA. Feminism & Psychology. 1991;1(2):201–219. [Google Scholar]

- Essed P. Vol. 2. Sage; 1991. Understanding everyday racism: An interdisciplinary theory. [Google Scholar]

- Forster M., Grigsby T.J., Rogers C.J., Benjamin S.M. The relationship between family-based adverse childhood experiences and substance use behaviors among a diverse sample of college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2018;76:298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster M., Grigsby T.J., Soto D.W., Sussman S.Y., Unger J.B. Perceived discrimination, cultural identity development, and intimate partner violence among a sample of Hispanic young adults. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2017;23(4):576. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillaumier A., Twyman L., Paul C., Siahpush M., Palazzi K., Bonevski B. Financial stress and smoking within a large sample of socially disadvantaged Australians. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017;14(3):231. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14030231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie B.J., Young A.M., Williams D.R., Boyd C.J., Kintner E.K. African American girls' smoking habits and day-to-day experiences with racial discrimination. Nursing Research. 2002;51(3):183–190. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200205000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman G.G. American community survey briefs, ACSBR/16-02. US Census Bureau, September; Washington: 2017. Household income: 2016.https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2017/acs/acsbr16-02.pdf [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp . IBM Corp; Armonk, NY: 2016. IBM SPSS statistics for windows (version 24.0) [Google Scholar]

- Jamal A., King B., Neff L., Whitmill J., Babb S., Graffunder C. Current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2005–2015. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2016;65 doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6544a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn J.R., Pearlin L.I. Financial strain over the life course and health among older adults∗. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2006;47(1):17–31. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamarck T. Psychosocial stress and cardiovascular disease: An exposure science perspective. Psychological Science Agenda. 2012;26(4) [Google Scholar]

- Kendzor D.E., Businelle M.S., Costello T.J., Castro Y., Reitzel L.R., Cofta-Woerpel L.M.…Cinciripini P.M. Financial strain and smoking cessation among racially/ethnically diverse smokers. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(4):702–706. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.172676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim G., Sellbom M., Ford K.-L. Race/ethnicity and measurement equivalence of the Everyday Discrimination Scale. Psychological Assessment. 2014;26(3):892–900. doi: 10.1037/a0036431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob G.F., Le Moal M. Stages and pathways of drug involvement: Examining the gateway hypothesis. 2002. Neurobiology of drug addiction; pp. 337–361. [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H., Klonoff E.A. The schedule of racist events: A measure of racial discrimination and a study of its negative physical and mental health consequences. Journal of Black Psychology. 1996;22(2):144–168. [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H., Klonoff E.A. Racial discrimination and cigarette smoking among Blacks: findings from two studies. Ethnicity & disease. 2000;10(2):195–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R.S. 1966. Psychological stress and the coping process. [Google Scholar]

- Levi L. Psychosocial stress and disease: A conceptual model. Life stress and illness. 1974:9–33. [Google Scholar]

- Levine S., Scotch N.A. 2013. Social stress: AldineTransaction. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco E.I., Unger J.B., Ritt-Olson A., Soto D., Baezconde-Garbanati L. Acculturation, gender, depression, and cigarette smoking among US Hispanic youth: The mediating role of perceived discrimination. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40(11):1519–1533. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9633-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco E.I., Unger J.B., Ritt-Olson A., Soto D., Baezconde-Garbanati L. A longitudinal analysis of Hispanic youth acculturation and cigarette smoking: The roles of gender, culture, family, and discrimination. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2012;15(5):957–968. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, E., & Medicine . The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2018. Public health consequences of E-cigarettes. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng D.M., Jeffery R.W. Relationships between perceived stress and health behaviors in a sample of working adults. Health Psychology. 2003;22(6):638. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.6.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen K., Marshall L., Hu S., Neff L., Control C.f.D., Prevention State-specific prevalence of current cigarette smoking and smokeless tobacco use among adults aged ≥18 years—United States, 2011–2013. MMWR. 2015;64(19):532–536. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott A.C. Stress modulation over the day in cigarette smokers. Addiction. 1995;90(2):233–244. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.9022339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyle S.A., Haddock C.K., Poston W.S.C., Bray R.M., Williams J. Tobacco use and perceived financial strain among junior enlisted in the US Military in 2002. Preventive Medicine. 2007;45(6):460–463. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan K.B. Crowdsourcing research: Data collection with Amazon's Mechanical Turk. Communication Monographs. 2017:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Siahpush M., Borland R., Scollo M. Smoking and financial stress. Tobacco Control. 2003;12(1):60–66. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.1.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siahpush M., Carlin J.B. Financial stress, smoking cessation and relapse: Results from a prospective study of an Australian national sample. Addiction. 2006;101(1):121–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siahpush M., Yong H.H., Borland R., Reid J.L., Hammond D. Smokers with financial stress are more likely to want to quit but less likely to try or succeed: Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Addiction. 2009;104(8):1382–1390. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02599.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slopen N., Dutra L.M., Williams D.R., Mujahid M.S., Lewis T.T., Bennett G.G.…Albert M.A. Psychosocial stressors and cigarette smoking among African American adults in midlife. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2012;14(10):1161–1169. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slopen N., Kontos E.Z., Ryff C.D., Ayanian J.Z., Albert M.A., Williams D.R. Psychosocial stress and cigarette smoking persistence, cessation, and relapse over 9–10 years: A prospective study of middle-aged adults in the United States. Cancer Causes & Control. 2013;24(10):1849–1863. doi: 10.1007/s10552-013-0262-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snider S.E., Cummings K.M., Bickel W.K. Behavioral economic substitution between conventional cigarettes and e-cigarettes differs as a function of the frequency of e-cigarette use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2017;177:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto C., Unger J.B., Ritt-Olson A., Soto D.W., Black D.S., Baezconde-Garbanati L. Cultural values associated with substance use among Hispanic adolescents in Southern California. Substance Use & Misuse. 2011;46(10):1223–1233. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.567366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits P.A. Stress and health: Major findings and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51(1_suppl):S41–S53. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- mTURK Tracker. (2017). Retrieved from http://demographics.mturk-tracker.com.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Atlanta, GA: 2014. The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: A report of the surgeon general. [Google Scholar]

- Unger J.B. Perceived discrimination as a risk factor for use of emerging tobacco products: More similarities than differences across demographic groups and attributions for discrimination. Substance Use & Misuse. 2018:1–7. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2017.1421226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger J.B., Ritt-Olson A., Teran L., Huang T., Hoffman B.R., Palmer P. Cultural values and substance use in a multiethnic sample of California adolescents. Addiction Research & Theory. 2002;10(3):257–279. [Google Scholar]

- Unger J.B., Rohrbach L.A., Cruz T.B., Baezconde-Garbanati L., Palmer P.H., Johnson C.A., Howard K.A. Ethnic variation in peer influences on adolescent smoking. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2001;3(2):167–176. doi: 10.1080/14622200110043086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger J.B., Shakib S., Gallaher P., Ritt-Olson A. Cultural/interpersonal values and smoking in an ethnically diverse sample of Southern California adolescents. Journal of Cultural Diversity. 2006;13(1):55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D.R., Yu Y., Jackson J.S., Anderson N.B. Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology. 1997;2(3):335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]