Abstract

Background:

The pomegranate peel extract is a rich source of natural antioxidant and antimicrobial activity. The aim of the present investigation was to evaluate the in vivo antifungal activity of the pomegranate peel extract and to compare it with nystatin against oral candidiasis in Wistar rats.

Methods:

Thirty-five male Wistar rats, 6 to 8 weeks old and 220 to 250 g in weight, were used for animal studies. The rats were randomly divided into 7 groups. All the rats, except the control group, were immunosuppressed with cyclosporine (40 mg/kg/d) and hydrocortisone acetate (500 µg/kg/d). Then oral candidiasis was induced via the oral administration of a suspension of Candida albicans (ATCC 10231) (2×107 cell/mL) in PBS on the palate and tongue of the animals on days 3 and 5. Treatment was initiated by using 3 different concentrations of the pomegranate peel extract (125, 250, and 500 µg/mL/kg) and nystatin 100000 U/mL/kg by gavage daily. The statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS, version 22.0. In this study, generalized estimating equations were used for data analysis to determine the effects of the pomegranate peel extract and nystatin on oral candidiasis.

Results:

Regardless of the concentration of the pomegranate peel extract used for the treatment of oral candidiasis, a significant improvement was seen after 15 days of treatment. All the doses of the pomegranate peel were effective against candidiasis after 15 days; the pomegranate peel extract had no adverse effects following administration in the rats.

Conclusion:

Our results indicated that the pomegranate peel extract is a promising approach to oral candidiasis treatment, and it may serve as a natural alternative prospect due to its potency against oral candidiasis.

Keywords: Candidiasis , Mouth , Antifungal agents , Animal experimentation , Pomegranate

What’s Known

Pomegranate peel extract contains active antifungal combinations, reported to have antifungal efficacy against Candida albicans.

What’s New

Saveh Sour malas cultivar of the pomegranate peel extract exhibited strong antifungal activity against Candida albicans and had effects comparable to nystatin, which is a standard treatment in oral candidiasis.

Topical treatment with the pomegranate peel extract was cost-effective and safe in treating oral candidiasis due to Candida albicans in the Wistar rats.

Pomegranate peel extract had no adverse effects following administration in the rats.

Introduction

The pomegranate peel extract has been reported to possess active antifungal compounds such as punicalagin, castagalagin, granatin, catechin, gallocatechin, kaempferol, and quercetin.1 The pomegranate peel contains punicalagin, which is a high source of antifungal activity against Candida albicans (C. albicans).2,3 The pomegranate peel extract has high synergism with some antifungal agents against Candida infections.2

Oral candidiasis is the most common human fungal infection, especially at the beginning and the end of life.4-6 Oral Candida is significantly more prevalent in patients with impaired salivary gland function, individuals using dentures, anticancer chemotherapy, high carbohydrate diet, diabetes mellitus, Cushing’s syndrome, malignancies, smoking, and immunosuppressive conditions.5

C. albicans is the most common species isolated from the oral cavity; it is associated with cell-mediated immune response defects and generally causes no problems in healthy conditions.7 The incidence rate of C. albicans isolated from the oral cavity has been reported to range from 20% to 75% in the general population with no symptoms,6 45% to 65% in neonates,6 30% to 45% in healthy children,7 30% to 45% in healthy adults,8 50% to 65% in individuals wearing removable dentures,9,10 65% to 88% among patients in the acute care unit,10,11 90% in patients undergoing chemotherapy for acute leukemia,12 and 95% in HIV patients.13

Increasing resistance to candidiasis treatment has potentially serious implications for the management of infections and it is an emerging public health problem. The rise in the incidence of clinical resistance to antifungal therapy and failure to respond in recent years underscores the need for the introduction of novel therapies and additional preventative and therapeutic options.14

Following our previous investigation, where we showed that the pomegranate peel extract could have antifungal activity against different varieties of Candida spp.,15 in the present study we evaluated the in vivo antifungal activity of the pomegranate peel extract against oral candidiasis.

The aim of the current study was to investigate the potential efficacy of the pomegranate peel extract as a safe and efficient alternative antifungal drug and to evaluate the in vivo antifungal activity of the Persian pomegranate peel extract against oral candidiasis and compare it with nystatin.

Materials and Methods

Plant Extraction

The Saveh Sour malas cultivar of the Persian pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) peel used in this study was collected from mature pomegranate fruits grown in the Agricultural Research Center of Saveh, Iran. The pomegranate peel extract was prepared by peeling, drying, and powdering the pomegranates. Five hundred grams of the dried powder of the pomegranate peel was extracted in a Soxhlet extractor by using methanol for 10 days.16 The solvent was removed in a rotary evaporator until dryness. The yield of the pomegranate peel extract was 69±0.9%. The stock peel extract was kept in sterile containers at 4 °C until use.

Animals

Thirty-five Wistar rats were obtained from the Animal House of Pasteur Institute of Iran. The male Wistar rats, 6 to 8 weeks old and 220 to 250 g in weight, were used for animal studies. The rats were randomly grouped; each experimental group consisted of 5 animals. The animals were kept under standard laboratory conditions of temperature (24±2 °C), humidity 50±5%, and light/dark cycle (12 h/12 h) and were given a standard diet.

The animals were housed in sanitized separate groups (5 rats in each cage) in polypropylene cages containing sterile paddy husk as bedding and had free access to standard and sterile pellet diet and water.

A 15-day study was performed to evaluate the repeated dose efficacy of the pomegranate peel extract and compare it with nystatin in the 35 Wistar rats according to the standard protocols of the Transitional Guidance on the Biocidal Products Regulation.17

Experimental Design

To induce oral candidiasis and the clinical signs of the disease, initially we investigated the time course effects of cyclosporine alone and its combination with hydrocortisone acetate in the induced oral candidiasis in the rat tongue in 2 groups, with each group consisting of 5 animals.

A total of 35 male Wistar rats were allocated to 7 groups, containing 5 animals in each group. The rats in all the groups, except the control group, were immunosuppressed. The first 3 groups of rats were administered with different concentrations of the pomegranate peel extract (500 µg/mL, 250 µg/mL, and 125 µg/mL), the fourth group was administered with nystatin (100000 U/kg/d), the fifth group was immunosuppressed and induced with oral candidiasis without treatment, the sixth group (control group) was not immunosuppressed and given only the pomegranate peel extract, and the seventh group was only immunosuppressed (table 1).

Table 1.

Evaluation of the therapeutic efficacy of the pomegranate peel extract (PPE) and nystatin against oral candidiasis in the rats

| Groups | Oral candidiasis induced | Number of cured | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | Day 5 | Day 10 | Day 15 | ||

| PPE-1 (500 mg/kg/d BW) | Infected (n=5) | 0 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| PPE-2 (250 mg/kg/d BW) | Infected (n=5) | 0 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| PPE (125 mg/kg/d BW) | Infected (n=5) | 0 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Nystatin | Infected (n=5) | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Positive control | Infected (n=5) | 0 | 0 1 dead | 0 1 dead | 0 1 dead |

| Non-immunosuppressed rats managed with PPE-2 (250 mg/kg/d BW) | Non-infected (n=5) | Not infected (negative culture) and without symptom | Not infected (negative culture) and without symptom | Not infected (negative culture) and without symptom | Not infected (negative culture) and without symptom |

| Immunosuppressed but neither infected nor treated | Non-infected (n=5) | Not infected (negative culture) and without symptom | Not infected (negative culture) and without symptom | Not infected (negative culture) and without symptom | Not infected (negative culture) and without symptom |

The pomegranate doses were chosen in accordance with our previously published paper.15 The antifungal activity of the pomegranate peel extract was examined using Candida spp. in microdilution assay. Complete inhibition of the growth of C. albicans in an in vitro culture was observed by the pomegranate extract at 0.250 mg/mL. Growth inhibition of more than 50% of the C. albicans was observed at 0.125 mg/mL of the pomegranate extract. No toxicity was observed in the rats treated by the pomegranate peel extract at different concentrations.

To elevate the rate of infection, we immunosuppressed the rats with cyclosporine A (40 mg/kg/d) and hydrocortisone acetate (500 μg/kg/d) for 5 days. Subsequently the rats were orally infected twice at day 3 and day 5 after immunosuppression therapy by administering 2×107 cells of C. albicans (ATCC 10231) in PBS on the palate and tongue with sterile cotton swabs.18 Sampling of the oral cavity and culturing on Sabouraud’s dextrose agar were done at 4 days after oral inoculation for infection monitoring. The culture media were incubated at 35 °C for 48 hours.

After the C. albicans were isolated in culture examination, treatment was started by the use of different concentrations of the pomegranate peel extract (500 µg/mL, 250 µg/mL, and 125 µg/mL) and nystatin (100000 U/kg/d) once a day on the tongue and oral cavity with a dropper. The doses were administered orally (by gavage) for 15 consecutive days (table 1). We used a model of oral candidiasis in the immunosuppressed rats that was previously reported by Krause and Schaffner.19 The evaluation of the therapeutic efficacy was by sampling performance according to C. albicans isolation of the culture at day 0, day 5, day 10, and day 15 after treatment. In the control group (only immunosuppressed), the animals were evaluated for systemic infections and they were sacrificed once their weight loss exceeded 25%. The additional group of rats, which were immunosuppressed but neither infected nor treated (n=5), showed a negative culture on day 0, day 5, day 10, and day 15 of the experiment.

The rats were sacrificed with an overdose of ketamine and xylazine at the end points of the course, and histopathological examinations of the tongue tissues were performed. After euthanasia of the rats, macroscopic examination of the oral cavity and tongue tissues was performed, and the tongue tissues were removed and prepared for histopathological study. The samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and phosphate mono sodic (NaH2PO4) and phosphate desodic (Na2HPO4) for histopathological examination. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Subsequently, histological evaluation of the presence of yeast and tissue reaction as well as the epithelial cell layer of the tongue with respect to disorganization of the basal layer, epithelial hyperplasia, and loss of filiform papilla was performed in each case.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical comparison was performed using the SPSS, version 22, and statistical methods of generalized estimating equations (to obtain consistent parameter estimates). The comparison of the results between the treatment and control groups was done using contingency tables and the χ2 test.

Experimental Design

The study design and animal experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Pasteur Institute of Iran (93/0201/3954-29 June, 2014), and the care of the laboratory animals was done in accordance with the regulations of the CPCSEA (Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals).20

Results

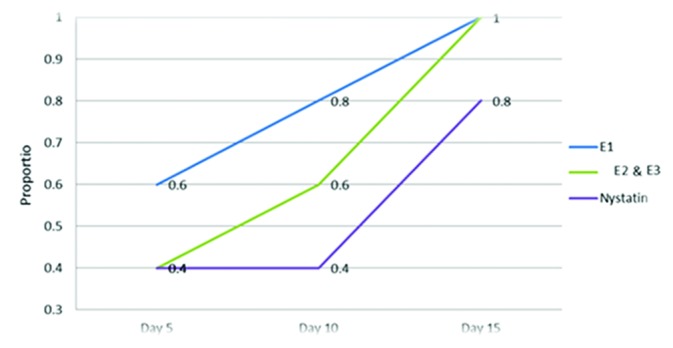

The results of treatment by the use of different concentrations of the pomegranate peel extract and nystatin as control are depicted in table 1. Therapeutic efficacy was evaluated on the basis of the extent of the yield of the fungal cultures from the infected tongue dorsum, palate, and buccal mucosa tissues and the relative number of the culture-negative rats at the end of the treatment period. The pomegranate peel extract was determined to be active against oral candidiasis due to C. albicans (ATCC 10231). Our results indicated that the pomegranate peel extract had high antifungal efficacy against oral candidiasis. Regardless of the concentration of the pomegranate peel extract used in the treatment of oral candidiasis, a significant reduction in the growth of C. albicans was seen 5,10,15 days after treatment when compared with the positive control group. The most effective concentration of the pomegranate peel extract was 500 µg/mL after 5 days. The evaluation of the therapeutic efficacy of the pomegranate peel extract showed 100% cure in all the doses after 15 days of treatment (figure 1).

Figure1.

Efficacy of the pomegranate peel extract evaluated in 3 concentrations (E1: 500, E2: 250, and E3: 125 µg/mg) and nystatin against Candida albicans after 5, 10, 15 days in the Wistar rats.

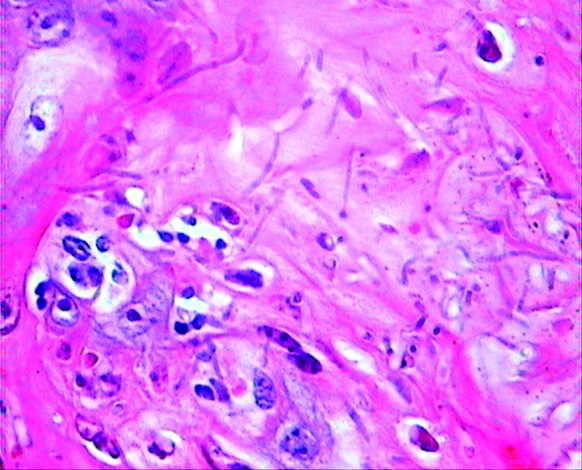

We compared the efficacy of the pomegranate peel extract and nystatin in oral candidiasis and observed no significant differences. The animals were evaluated as a Candida infection in the control group (immunosuppressed without treatment) when they had a weight loss between 15% and 25%. In the untreated control group, 4 of the 5 animals were sacrificed before the end of the investigation period time due to a weight loss exceeding 25%. After the last untreated rat in this group was sacrificed at day 15, pseudohyphae and yeasts were seen in the keratinized epithelial layer of the tongue and in microscopic view, subepithelial infiltrated inflammatory cells consisting of mainly monocytes and only a few polynuclear cell infiltrations were observed (figure 2). The pomegranate peel extract exerted no adverse effects following administration in the Wistar rats in the overall control group and after the treatment with the pomegranate peel extract in the other groups.

Figure2.

Histopathologic section of the dorsal tongue of the Wistar rat, showing yeasts and hyphae in the stratified squamous epithelium and intraepithelial micro abscesses. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E): magnification, 600×.

There was no significant difference between the 4 intervention groups at the end of the examination time. Figure 1 shows similar patterns observed at day 15, and E1, E2, and E3 had 100% and nystatin had 80% efficacy.

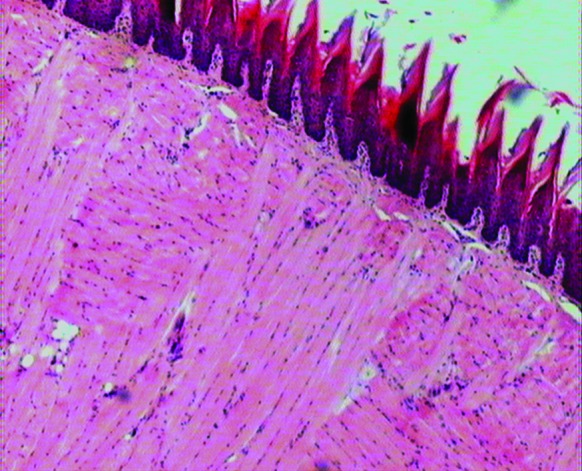

In the current study, immunosuppression with cyclosporine and hydrocortisone acetate rendered the Wistar rats susceptible to oropharyngeal candidiasis. Oral candidiasis was established with a strong positive Candida culture 5 days after Candida inoculation. The animals became ill, and a significant weight loss of up to 15% to 25%, anorexia, and decrease in activity were observed. Red and white plaques and inflammation on the animals’ tongue dorsum, palate, and buccal mucosa, suggestive of oral candidiasis, were observed in all the groups except for the overall control group (figure 3). C. albicans were isolated and identified by culture in all the groups exposed to Candida inoculation, except in the overall control group. Histopathologic sections of the dorsal tongue of the Wistar rats in the negative control group, immunosuppressed and induced with oral candidiasis without treatment, showed yeasts and hyphae in the stratified squamous epithelium of the tongue and intraepithelial micro abscesses (). The histologic and morphologic characteristics of the tongues of the Wistar rats after treatment showed normal filiform papillae, epithelium, lamina propria, and muscular core under light microscopy (figure 4).

Figure3.

Macroscopic appearance of the typical lesions of oral candidiasis observed on the Wistar rat’s tongue infected with Candida albicans after immunosuppression therapy administration.

Figure4.

Macroscopic appearance of the histopathologic section of the dorsal tongue of the Wistar rat after treatment, illustrating normal filiform papillae, epithelium, lamina propria, and muscular core. (Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E): magnification 80×.

Discussion

The importance of natural products in the treatment of human diseases is well documented. Traditional medicine has played an important role in the civilization and culture of Iran. Originally, pomegranates (Punica granatum L.) were grown in Mediterranean regions, and nowadays they have become one of the main cultivated productions in Iran with a wide use for different therapeutic purposes.22

The increase in drug-resistance in recent years and the possibility of widespread pandemics have created the need for preventive and therapeutic options in addition to conventional drugs.23 Because of the presence of various chemical components such as phenolic, flavonoid, and antioxidant molecules as well as anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial effects, pomegranates have the potential to be used in many clinical applications.24 Recent studies have demonstrated that the pomegranate peel extract may serve as an attractive natural alternative prospect owing to its potency against wide varieties of bacterial and fungal pathogens.1,25-27 The active inhibitors in the pomegranate peel, including phenolics and flavonoids, have been demonstrated in phytochemical analyses.28 Wide varieties of phytochemical compounds in the pomegranate peel extract have indicated antimicrobial efficacy.29

In the present study, we sought to evaluate the pomegranate peel extract activity against oral candidiasis in an immunosuppressed rat model using both cyclosporine and hydrocortisone acetate to induce oral candidiasis.

Rat models have a sufficiently sized oral cavity, and hyposalivatory conditions to induce oral candidiasis contribute to the development of lesions similar to human oral candidiasis.18 Oral candidiasis in the rat model has also been used to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of topical oral antifungals used to treat this condition.30 This model enabled us to study the clinical pathogenesis of the infection and to evaluate the antifungal activity of the pomegranate peel extract. Cyclosporine A acts as an antilymphocytic agent and is active following parenteral or oral administration in rats, mice, and guinea pigs.31 Cyclosporine A selectively damages T-cell-mediated immunity and natural killer cell activity32 without impairing nonspecific phagocytic resistance.33C. albicans and some other human pathogenic Candida spp. are not natural commensal/pathogens in rats.34 It is, therefore, necessary to chemically induce immunosuppression before oral candidiasis can be observed in rats.

Our findings showed that cyclosporine in combination with hydrocortisone acetate provoked oral Candidal lesions in all the rats (100%) after 5 days without affecting systemic candidiasis. On the other hand, cyclosporine alone provoked oral Candidal thrush-like lesions in 60% of the rats after 5 days. We did not observe the disseminated infection in the rats that had received cyclosporine or cortisone acetate at 10 mg and 1 mg/kg/d, respectively. The results of the present study showed that cyclosporine A had no effect on systemic candidiasis by C. albicans.

This clinically relevant animal model of oral candidiasis is valuable for the studies of fungal immunity and antifungal therapy in oral infections.

We observed a considerable reduction in oral candidiasis by the employment of different concentrations of the pomegranate peel extract in the immunosuppressed rat model.

These findings and the results obtained in our current and previous studies clearly confirmed the effectiveness of the pomegranate peel extract in the inhibition of fungal activity. To choose the pomegranate concentration in this study, we mainly focused on the already published data from our previous work,15 where we studied the antifungal activity of 8 cultivars of the pomegranate peel extract in vitro by minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) against 5 standard Candida spp. The Saveh Sour malas cultivar indicated the greatest antifungal activity, with MIC values of 125 μg/mL and less against all the 5 Candida strains. Accordingly, we chose 125 μg/mL as the minimum concentration, 250 μg/mL as the medium concentration, and 500 μg/mL as the maximum concentration. Abdollahzadeh et al.35 (2010) demonstrated that the pomegranate peel extract could be used in the control of oral pathogens.

The results obtained from the current study showed that the Saveh Sour malas cultivar, grown in the Saveh region of Markazi Province of Iran, had potential antifungal activity. In a comparative study between the antioxidant activity and the flavonoid contents of Persian pomegranates, Shams Ardekani et al. The results obtained from the current study showed that the Saveh Sour malas cultivar, grown in the Saveh region of Markazi Province of Iran, had potential antifungal activity. In a comparative study between the antioxidant activity and the flavonoid contents of Persian pomegranates, Shams Ardekani et al.36 suggested that amongst the 9 different cultivars of pomegranates, the peel extracts of Saveh Sour malas, Sour summer, and Black peel were good sources for the extraction and purification of phenolic and flavonoid compounds due to their high polyphenolic and flavonoid compounds. The authors also reported that the total polyphenolic compound of Saveh malas was 216.74±19.01 mg gallic acid equivalent (GAE)/g of the extract and its total flavonoid was 34.71±1.34 mg catechin equivalent (CE)/g. The results indicated that the antimicrobial efficacy of the pomegranate peel was attributed to the total phenolics. The methanolic pomegranate peel extract gave the highest total yield in comparison with water, ethanol, acetone, and ethyl acetate extracts.37

In our previous study, we showed that the pomegranate peel extract had no adverse effects following administration in BALB/c mice.38 The pomegranate peel extract exhibited strong antifungal activity against C. albicans, which was comparable with nystatin as a standard treatment in oral Candida infections. Our study chimes in with those done by other investigators on the efficacy of the pomegranate peel extract in preventing the growth of Candida spp. 2,15,39,40

The use of standard antifungal treatment can be limited because of toxicity and low efficacy rates. We found that topical treatment with the pomegranate peel extract was cost-effective and safe in treating oral candidiasis due to C. albicans in Wistar rats. Mansourian et al.41 reported that the pomegranate peel extract had definite anti-Candida activity in an in vitro well agar diffusion method. Similarly, Endo et al.42 reported that the pomegranate peel extract was a potent inhibitor for C. albicans. In another study, Tayel et al.40 showed that the application of the pomegranate peel extract aerosol was an efficient method for complete sanitization and prevention against C. albicans growth in semi-closed places.

In addition, the inhibitory effects of Punica granatum against mycelial fungi have been reported before.43,44 A study by Foss et al. indicated that the pomegranate peel crude extract had antifungal activity against dermatophytes including Trichophyton rubrum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Microsporum canis, and Microsporum gypseum. 15

Immunosuppressed and old patients with various health problems are generally more susceptible to adverse drug effects; they are at specific risk for oral Candida infections. Oral treatment may be preferred in these patients, who are unable to tolerate other oral synthetic antifungal agents due to adverse effects and drug interactions.

The pomegranate peel extract exhibited high activity against oral candidiasis, which was comparable with nystatin. Thus, topical treatment of oral candidiasis by the application of the pomegranate peel extract solution, as an effective treatment for oral candidiasis, had high antifungal efficacy against oral candidiasis. Indeed, its values were comparable to those of nystatin or the gold standard treatment. We would, therefore, suggest the new option of the application of the pomegranate peel extract as an effective treatment for oral candidiasis in that it is a simple, nontoxic, safe, tolerable, inexpensive repeatable therapy with a low potential for drug interactions and without fungal resistance risk. Furthermore, the Wistar rat is a potential model for evaluating oral candidiasis treatment.

Conclusion

Our results indicated that the pomegranate peel extract is an in vivo inhibitor of oral Candida infection and as such would be a suitable target for research aimed at obtaining a new anti-Candida agent.

The availability of the oral formulation of a natural antifungal product with high biosafety makes it an appropriate Candidate for prophylactic or prolonged maintenance therapy. The current in vivo assessment highlights the need for clinical pharmacokinetic studies to determine the interaction potential of a natural product with a view to developing a formulation for the treatment of oral infections.

Acknowledgement

This work was part of PhD studies conducted by Shahindokht Bassiri-Jahromi, at the Department of Medical Mycology, Pasteur Institute of Iran. The authors thank the Council of Research, Pasteur Institute of Iran, for financial support and scholarships (May 2, 2012/TP-9003).

Conflict of Interest:None declared.

References

- 1.Dahham SS, Ali MN, Tabassum H, Khan M. Studies on antibacterial and antifungal activity of pomegranate (Punica granatum L) Am Eurasian J Agric Environ Sci. 2010;9:273–81. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Endo EH, Cortez DA, Ueda-Nakamura T, Nakamura CV, Dias Filho BP. Potent antifungal activity of extracts and pure compound isolated from pomegranate peels and synergism with fluconazole against Candida albicans. Res Microbiol. 2010;161:534–40. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akpan A, Morgan R. Oral candidiasis. Postgrad Med J. 2002;78:455–9. doi: 10.1136/pmj.78.922.455. [ PMC Free Article] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abu-Elteen KH, Abu-Alteen RM. The prevalence of Candida albicans populations in the mouths of complete denture wearers. New Microbiol. 1998;21:41–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manning DJ, Coughlin RP, Poskitt EM. Candida in mouth or on dummy? Arch Dis Child. 1985;60:381–2. doi: 10.1136/adc.60.4.381. [ PMC Free Article] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berdicevsky I, Ben-Aryeh H, Szargel R, Gutman D. Oral Candida in children. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;57:37–40. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(84)90257-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arendorf TM, Walker DM. The prevalence and intra-oral distribution of Candida albicans in man. Arch Oral Biol. 1980;25:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(80)90147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lucas VS. Association of psychotropic drugs, prevalence of denture-related stomatitis and oral candidosis. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1993;21:313–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1993.tb00782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cumming CG, Wight C, Blackwell CL, Wray D. Denture stomatitis in the elderly. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1990;5:82–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1990.tb00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aldred MJ, Addy M, Bagg J, Finlay I. Oral health in the terminally ill: a cross-sectional pilot survey. Spec Care Dentist. 1991;11:59–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1991.tb00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holbrook WP, Hjorleifsdottir DV. Occurrence of oral Candida albicans and other yeast-like fungi in edentulous patients in geriatric units in Iceland. Gerodontics. 1986;2:153–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodu B, Carpenter JT, Jones MR. The pathogenesis and clinical significance of cytologically detectable oral Candida in acute leukemia. Cancer. 1988;62:2042–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19881101)62:9<2042::aid-cncr2820620928>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Durden FM, Elewski B. Fungal infections in HIV-infected patients. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1997;16:200–12. doi: 10.1016/s1085-5629(97)80043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wise R, Hart T, Cars O, Streulens M, Helmuth R, Huovinen P, et al. Antimicrobial resistance. Is a major threat to public health. BMJ 1998;317:609–10. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7159.609. [ PMC Free Article] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bassiri-Jahromi S, Katiraee F, Hajimahmoodi M, Mostafavi E, Talebi M, Pourshafie MR. In vitro antifungal activity of various Persian cultivars of Punica granatum L. extracts against Candida species. Jundishapur J Nat Pharm Prod. 2015;10:e19754. doi: 10.17795/jjnpp-19754. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Negi P, Jayaprakasha G, Jena B. Antioxidant and antimutagenic activities of pomegranate peel extracts. Food Chemistry. 2003;80:393–7. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(02)00279-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. FB Engineering [Internet] Swedish chemicals agency (Kemikalieinspektionen), department of pesticides and biotechnical products. c2012- [cited 2015 May 2] Available from: [http://www.kemi.se/global/bekampningsmedel/biocidprodukter/efficacy-testing-of-biocidal-products-overview-of-available-tests_asw_fbe_080305_final.pdf?id=1443. ]

- 18.Costa AC, Pereira CA, Junqueira JC, Jorge AO. Recent mouse and rat methods for the study of experimental oral candidiasis. Virulence. 2013;4:391–9. doi: 10.4161/viru.25199. [ PMC Free Article] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krause MW, Schaffner A. Comparison of immunosuppressive effects of cyclosporine A in a murine model of systemic candidiasis and of localized thrushlike lesions. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3472–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.11.3472-3478.1989. [ PMC Free Article] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.CPCSEA [Internet] The Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals (CPCSEA). [cited 2015 August 27] Available from: [http://cpcsea.nic.in/Auth/index.aspx. ]

- 21.Dias DA, Urban S, Roessner U. A historical overview of natural products in drug discovery. Metabolites. 2012;2:303–36. doi: 10.3390/metabo2020303. [ PMC Free Article] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zarfeshany A, Asgary S, Javanmard SH. Potent health effects of pomegranate. Adv Biomed Res. 2014;3:100. doi: 10.4103/2277-9175.129371. [ PMC Free Article] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howell AB, D’Souza DH. The pomegranate: Effects on bacteria and viruses that influence human health. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:606212. doi: 10.1155/2013/606212. [ PMC Free Article] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rahimi HR, Arastoo M, Ostad SN. A Comprehensive Review of Punica granatum (Pomegranate) Properties in Toxicological, Pharmacological, Cellular and Molecular Biology Researches. Iran J Pharm Res. 2012;11:385–400. [ PMC Free Article] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCarrell EM, Gould SW, Fielder MD, Kelly AF, El Sankary W, Naughton DP. Antimicrobial activities of pomegranate rind extracts: nhancement by addition of metal salts and vitamin C. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2008;8:64. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-8-64. [ PMC Free Article] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shuhua Q, Hongyun J, Yanning Z. Inhibitory effects of Punica granatum peel extracts on Botrytis cinerea. Plant Protection. 2010;36:148–50. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Braga LC, Shupp JW, Cummings C, Jett M, Takahashi JA, Carmo LS, et al. Pomegranate extract inhibits Staphylococcus aureus growth and subsequent enterotoxin production. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;96:335–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Zoreky NS. Antimicrobial activity of pomegranate (Punica granatum L. ) fruit peels. Int J Food Microbiol 2009;134:244–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sadeghian A, Ghorbani A, Mohamadi-Nejad A, Rakhshandeh H. Antimicrobial activity of aqueous and methanolic extracts of pomegranate fruit skin. Avicenna J Phytomed. 2011;1:67–73. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Samaranayake YH, Samaranayake LP. Experimental oral candidiasis in animal models. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:398 –429. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.2.398-429.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schaffner A, Douglas H, Davis CE. Models of T cell deficiency in listeriosis: the effects of cortisone and cyclosporin A on normal and nude BALB/c mice. J Immunol. 1983;131:450–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borel JF, Feurer C, Magnee C, Stahelin H. Effects of the new anti-lymphocytic peptide cyclosporin A in animals. Immunology. 1977;32:1017–25. [ PMC Free Article] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shevach EM. The effects of cyclosporin A on the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 1985;3:397–423. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.03.040185.002145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vecchiarelli A, Cenci E, Marconi P, Rossi R, Riccardi C, Bistoni F. Immunosuppressive effect of cyclosporin A on resistance to systemic infection with Candida albicans. J Med Microbiol. 1989;30:183–92. doi: 10.1099/00222615-30-3-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abdollahzadeh S, Mashouf R, Mortazavi H, Moghaddam M, Roozbahani N, Vahedi M. Antibacterial and antifungal activities of punica granatum peel extracts against oral pathogens. J Dent (Tehran) 2011;8:1–6. [ PMC Free Article] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shams Ardekani MR, Hajimahmoodi M, Oveisi MR, Sadeghi N, Jannat B, Ranjbar AM, et al. Comparative Antioxidant Activity and Total Flavonoid Content of Persian Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) Cultivars. Iran J Pharm Res. 2011;10:519–24. [ PMC Free Article] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Z, Pan Z, Ma H, Atungulu GG. Extract of phenolics from pomegranate peels. The Open Food Science Journal. 2011;5:17–25. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jahromi SB, Pourshafie MR, Mirabzadeh E, Tavasoli A, Katiraee F, Mostafavi E, et al. Punica granatum Peel Extract Toxicity in Mice. Jundishapur J Nat Pharm Prod. 2015;10 :e23770. doi: 10.17795/jjnpp-23770. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anibal PC, Peixoto IT, Foglio MA, Hofling JF. Antifungal activity of the ethanolic extracts of Punica granatum L. and evaluation of the morphological and structural modifications of its compounds upon the cells of Candida spp. Braz J Microbiol 2013;44:839–48. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822013005000060. [ PMC Free Article] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tayel AA, El-Tras WF. Anticandidal activity of pomegranate peel extract aerosol as an applicable sanitizing method. Mycoses. 2010;53:117–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mansourian A, Boojarpour N, Ashnagar S, Momen Beitollahi J, Shamshiri AR. The comparative study of antifungal activity of Syzygium aromaticum, Punica granatum and nystatin on Candida albicans; an in vitro study. J Mycol Med. 2014;24:e163–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Endo EH, Ueda-Nakamura T, Nakamura CV, Filho BP. Activity of spray-dried microparticles containing pomegranate peel extract against Candida albicans. Molecules. 2012;17:10094–107. doi: 10.3390/molecules170910094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tayel A, El-Baz A, Salem M, El-Hadary M. Potential applications of pomegranate peel extract for the control of citrus green mould/Mögliche Anwendungen von Granatapfel-Schalenextrakten zur Bekämpfung der Grünfäule der Zitrusfrüchte. Journal of Plant Diseases and Protection. 2009;116:252–6. doi: 10.1007/BF03356318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Foss SR, Nakamura CV, Ueda-Nakamura T, Cortez DA, Endo EH, Dias Filho BP. Antifungal activity of pomegranate peel extract and isolated compound punicalagin against dermatophytes. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2014;13:32. doi: 10.1186/s12941-014-0032-6. [ PMC Free Article] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]