Abstract

X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (X-SCID) has been successfully treated by hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) transduction with retroviral vectors expressing the interleukin-2 receptor subunit gamma gene (IL2RG), but several patients developed malignancies due to vector integration near cellular oncogenes. This adverse side effect could in principle be avoided by accurate IL2RG gene editing with a vector that does not contain a functional promoter or IL2RG gene. Here, we show that adeno-associated virus (AAV) gene editing vectors can insert a partial Il2rg cDNA at the endogenous Il2rg locus in X-SCID murine bone marrow cells and that these ex vivo-edited cells repopulate transplant recipients and produce CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Circulating, edited lymphocytes increased over time and appeared in secondary transplant recipients, demonstrating successful editing in long-term repopulating cells. Random vector integration events were nearly undetectable, and malignant transformation of the transplanted cells was not observed. Similar editing frequencies were observed in human hematopoietic cells. Our results demonstrate that therapeutically relevant HSC gene editing can be achieved by AAV vectors in the absence of site-specific nucleases and suggest that this may be a safe and effective therapy for hematopoietic diseases where in vivo selection can increase edited cell numbers.

Keywords: AAV vector, genome editing, hematopoietic stem cells

Hiramoto et al. demonstrate that AAV-mediated gene editing could become a therapy for genetic immunodeficiencies, such as X-SCID, in which corrected cells preferentially expand. It may be safer than other approaches due to the absence of both a nuclease and genetic elements that could turn on oncogenes.

Introduction

The interleukin-2 receptor gamma protein (IL2RG) is a common subunit of the receptors for interleukins-2, -4, -7, -9, -15, and -21.1 Pathogenic mutations in the IL2RG gene cause X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (X-SCID), which is characterized by the complete absence of T cells and natural killer (NK) cells, and the presence of non-functional B cells.2, 3 X-SCID has been successfully treated by hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) transduction with retroviral vectors expressing the IL2RG gene,4, 5 but several patients developed malignancies due to vector integration near cellular oncogenes.6 These seminal adverse events and related cases in patients treated for Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome7 and chronic granulomatous disease8 have highlighted the risks of randomly integrating vectors containing strong promoter and enhancer elements and stimulated a search for safer vectors. Gene editing offers an ideal therapeutic option, because vectors can be designed to lack promoters and enhancers, and random integration can be minimized.

We previously reported successful gene editing in several primary human cell types and at multiple genomic loci by recombinant vectors based on the non-pathogenic adeno-associated virus (AAV).9, 10, 11, 12 AAV gene editing vectors have a single-stranded, linear DNA genome (∼4.7 kb) with inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) and an internal targeting cassette homologous to the target locus except for the central sequence change being introduced. In the absence of nuclease-induced breaks, AAV-mediated gene editing is thought to occur by pairing of the single-stranded vector genome at the lagging strand of the replication fork and incorporation into the newly synthesized DNA strand in a process analogous to Okazaki fragment ligation.13 This model is supported by experiments showing that single-stranded (and not double-stranded) vector genomes participate in the reaction,14, 15 S phase is required for editing,16 there is a ∼10-fold vector strand preference for editing,14 editing is coordinated with replication fork direction,13 and the chromosomal target site is accurately edited.17 Site-specific nucleases can also be used to enhance AAV-mediated gene editing, in which case the AAV vector genome serves as a donor template for homology-directed repair18; however, this approach is complicated by the need for nuclease delivery, possible off-target cleavage events, and inaccurate double-strand break (DSB) repair by non-homologous end joining. Here, we explore the use of nuclease-free, AAV-mediated gene editing as a safer, more accurate therapeutic gene editing strategy, using X-SCID as a disease model.

Results

Development of T Cells after Il2rg Editing in X-SCID Bone Marrow Cells

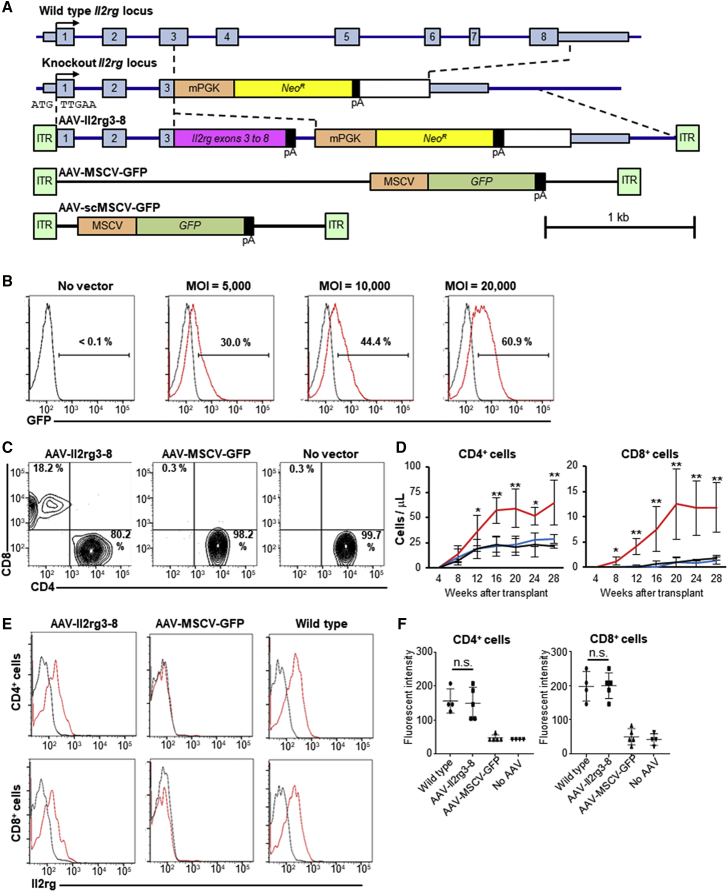

We constructed an AAV vector homologous to the deleted Il2rg locus in X-SCID mice19 but containing a partial Il2rg cDNA at exon 3 (Figure 1A). AAV-Il2rg3-8 does not include the Il2rg promoter or initiation codon, so random integration events will not lead to Il2rg expression, but homologous recombination at the endogenous locus creates a complete Il2rg reading frame expressed from the Il2rg promoter. AAV-scMSCV-GFP is a self-complementary control vector that does not require second strand synthesis or annealing to express GFP from its murine stem cell virus (MSCV) promoter. AAV-scMSCV-GFP packaged in serotype 6 capsids20 transduced over 60% of Lineageneg, Sca-1+, c-Kit+ (LSK) cells at an MOI of 20,000 genome-containing vector particles/cell (Figure 1B), confirming that serotype 6 vectors efficiently enter hematopoietic cells.18, 21 The full-length control vector AAV-MSCV-GFP was used in transplantation experiments to more accurately model the similarly sized AAV-Il2rg3-8 vector.

Figure 1.

AAV-Mediated Gene Editing Restores T Cell Il2rg Expression

(A) Wild-type and knockout Il2rg loci are shown with AAV vector maps. (B) GFP expression in vitro in AAV-scMSCV-GFP-transduced (red lines) or no vector (black lines) LSK cells 2 days after infection is shown. (C) Representative CD4+ and CD8+ populations in CD3+ cells from mice treated with the indicated vectors 32 weeks after transplant are shown. (D) CD4+ and CD8+ cell counts over time in the peripheral blood of mice (n = 16 for each group) treated with AAV-Il2rg3-8 (red lines), AAV-MSCV-GFP (blue lines), or no vector (black lines) are shown. Data are presented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 (two-way ANOVA). (E) Representative Il2rg surface expression (red lines) and isotype (black lines) in CD4+ and CD8+ cells from treated mice 20 weeks are shown. (F) Mode fluorescent intensity of Il2rg in CD4+ and CD8+ cells. Data are presented as mean ± SD. n.s., no significant difference (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). Each symbol represents a distinct mouse.

X-SCID mouse bone marrow (BM) cells were infected overnight with AAV vectors and then delivered by intravenous injection into irradiated X-SCID recipients. AAV-Il2rg3-8-treated mice developed circulating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells that increased in number over time, which did not occur in mice that received AAV-MSCV-GFP-infected or uninfected cells (Figures 1C and 1D). The circulating T cells expressed Il2rg on their cell surface (Figure 1E), and the levels were statistically indistinguishable from that of wild-type cells (Figure 1F), demonstrating properly regulated expression of the Il2rg transcript at the edited locus. The levels of other peripheral blood cell types in AAV-Il2rg3-8-treated mice were unchanged from controls, except for a modest increase in circulating monocytes (Figures S1A and S1C). Circulating NK cell numbers were not significantly changed in treated mice (Figures S1B and S1C), although they require Il2rg-mediated signaling for their formation.22, 23 Selective expansion of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells was also observed in the spleens of AAV-Il2rg3-8-treated mice (Figure S2). These results are consistent with in vivo selection and expansion of edited T cells, but not of edited myeloid cells, B cells, or their precursors.

Detection of Edited Alleles

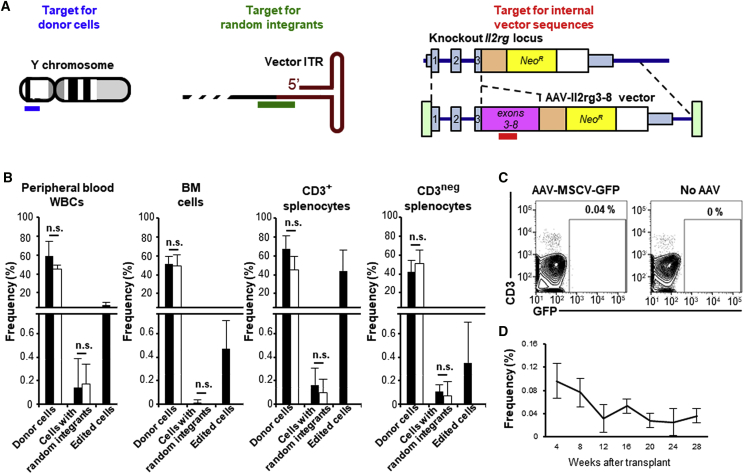

We measured the frequency of transduced cells in the transplanted mice by qPCR with primers designed to detect either donor cells (Y chromosome sequences), cells containing randomly integrated vector genomes (AAV vector sequences outside of the homology arms), or all transduced cells (Il2rg exon 5 sequences only found in the AAV-Il2rg3-8 vector genome; Figure 2A). The frequency of edited cells was then calculated by subtracting the random integration frequency from the frequency of all transduced cells. We note that, whereas random AAV vector integrants may have terminal deletions of varying sizes, the vast majority of integrated genomes are expected to contain the sequences amplified in this assay based on large-scale studies of vector integration in human and mouse cells.24, 25 qPCR analysis was performed on circulating white blood cells (WBCs), BM cells, and CD3+ or CD3neg splenocytes 32 weeks after transplantation (Figure 2B). Substantial donor cell marking (32%–62%) was found in all samples, regardless of the vector used. Edited cells constituted ∼10% of the peripheral blood WBCs of AAV-Il2rg3-8-treated mice and a higher proportion of their CD3+ splenocytes (>58% of donor cells), whereas edited BM cells and CD3neg splenocytes were present at significantly lower levels (<1%). In general, the qPCR-based editing frequencies correlated with the frequency of CD3+ cells in each sample, confirming that the increase in T cell numbers represented edited cells. Although random integration frequencies were detectable, they were extremely rare (<0.4%) in all samples, despite the fact that most of the cells presumably contained biologically active vector genomes soon after infection (see Figure 1B). This was confirmed by measuring GFP expression in AAV-MSCV-GFP-treated mice, which showed that ∼0.04% of peripheral blood WBCs were GFP+ and persisted for at least 28 weeks after transplant (Figures 2C and 2D).

Figure 2.

Detection of Vector Sequences in the Genomic DNA of Treated Mice

(A) The qPCR products used to detect donor cells (blue bar), random integrants (green bar), and internal vector sequences (edited alleles or random integrants, red bar) are shown. (B) The frequency of donor cells, cells with random integrants, and edited cells (internal vector sequence frequency minus random integrant frequency) as determined by qPCR of DNA from peripheral blood WBCs, bone marrow cells, CD3+ splenocytes, and CD3neg splenocytes of mice treated with AAV-Il2rg3-8 (black columns) or AAV-MSCV-GFP (white columns) 32 weeks after transplant (n = 4 of each) is shown. Total DNA amounts were determined by amplifying the Bcl2 gene (primers not shown) and used to calculate frequencies. Data are presented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 (two-tailed t test). (C) Representative GFP expression in peripheral blood WBCs at 28 weeks post-transplant is shown. (D) The frequency of GFP+ cells over time in the peripheral blood WBCs of mice treated with AAV-MSCV-GFP (n = 16) is shown. Data are presented as mean ± SD.

We also amplified an edited allele-specific PCR product from the CD3+ cells of AAV-Il2rg3-8-treated mice by long-range PCR with primers inside the vector and outside the homology arms. This PCR product had unique chromosomal and vector sequences that could only be due to Il2rg gene editing (Figure S3A). Similarly, the sequence of an mRNA amplified by RT-PCR from the CD3+ splenocytes of treated mice showed chromosomal- and vector-specific sequences (Figure S3B), confirming that accurate Il2rg gene editing had occurred. The entire Il2rg coding region of this mRNA was identical to the spliced, wild-type transcript.

Lymphocyte Recovery in Secondary Transplant Recipients

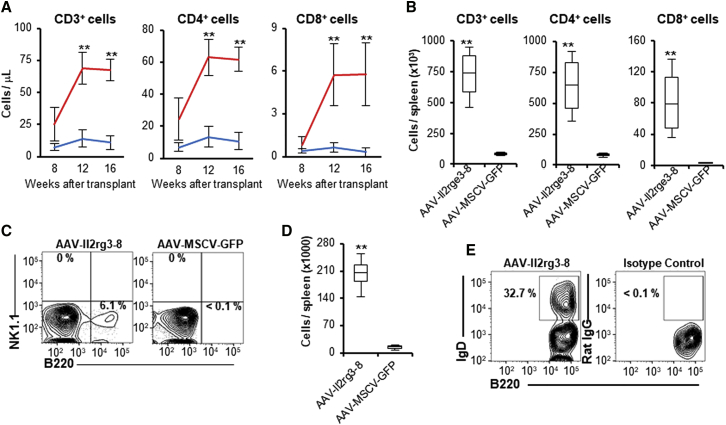

BM cells were isolated from treated mice 20–32 weeks after transplantation and used to transplant additional X-SCID mice. Secondary recipients of AAV-Il2rg3-8-treated BM cells had increases in peripheral blood lymphocytes over time, including CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ cells that by 16 weeks reached levels slightly below those of primary recipients (Figures 3A, S4A, and S4B). These secondary recipients also had a modest increase in peripheral blood monocytes and no increase in circulating granulocytes, NK cells, or B cells as compared to AAV-MSCV-GFP-treated controls (Figures S4C and S4D), suggesting that the edited T cells were selectively expanding in vivo. The spleens of secondary AAV-Il2rg3-8-treated recipients also contained T cells, with CD3+ and CD4+ cells present at higher levels than in primary recipients (Figure 3B). These combined results show that long-term repopulating cells were edited and that their progeny continued to increase in number in secondary recipients. These repopulating cells could be true hematopoietic stem cells or more committed lymphoid progenitors that retained proliferative potential. In contrast to primary transplant recipients, the spleens of AAV-Il2rg3-8-treated secondary recipients contained ∼6% B220+ cells and a total of 2 × 105 B cells per spleen (Figures 3C and 3D). Approximately one-third of these B cells were immunoglobulin D (IgD)+ (Figure 3E), demonstrating that antibody gene rearrangement had occurred.26

Figure 3.

Edited Lymphocytes Increase in Secondary Transplant Recipients

(A) Time course of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ cells in the peripheral blood of secondary transplant recipients that received bone marrow cells from mice treated with AAV-Il2rg3-8 (n = 8; red lines) or AAV-MSCV-GFP (n = 4; blue lines). Data are presented as mean ± SD. **p < 0.01 (two-way ANOVA). (B) The total number of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ cells in the spleens of secondary recipients 20 weeks after secondary transplant is shown. Data are presented as mean ± SD. **p < 0.01 (two-tailed t test). (C) Representative flow cytometry shows B and NK cell populations in the spleens. (D) The total number of B cells in these spleens is shown. Data are presented as mean ± SD. **p < 0.01 (two-tailed t test). (E) Representative flow cytometry analysis shows mature B cells (IgD+; B220+) in the splenocytes of an AAV-Il2rg3-8-treated secondary recipient.

Edited T Cell Characterization and Responses

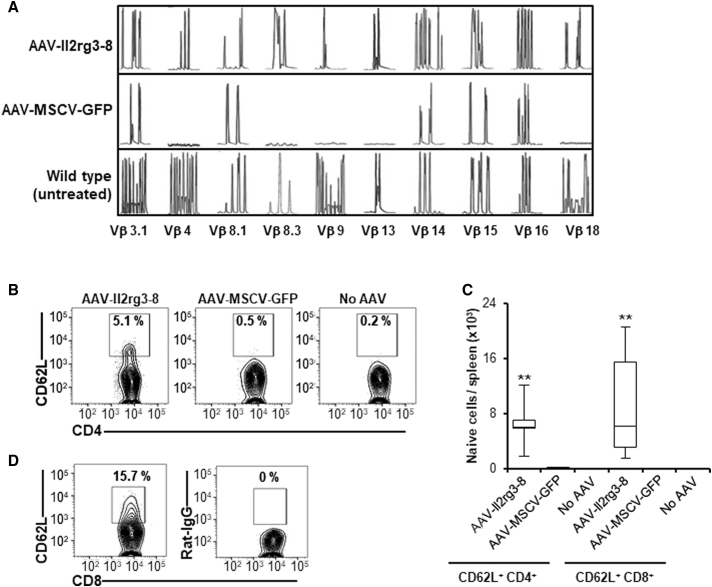

A key indicator of successful X-SCID gene therapy is the development of a diverse T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire. We examined the TCR Vβ genes of CD3+ splenocytes from primary transplant recipients by PCR amplification of CDR3 variant beta chain regions. The repertoire of AAV-Il2rg3-8-treated mice was similar to that of wild-type mice and more diverse than that of AAV-MSCV-GFP-treated mice (Figure 4A). In addition, naive (CD62L+) CD4+, and CD8+ cells were both increased by AAV-Il2rg3-8 treatment (Figures 4B–4D). Naive T cells can differentiate into several types of helper and cytotoxic effector cells after encountering their cognate antigens and are absent in X-SCID mice, suggesting that gene editing can help establish the complex regulatory networks required for effective immunity.

Figure 4.

Edited T Cell Characterization

(A) Analysis of TCR Vβ repertoire in the CD3+ splenocytes of untreated wild-type mice and X-SCID mice treated with AAV-Il2rg3-8 or AAV-MSCV-GFP. (B and C) Representative flow cytometry (B) of naive CD4+ splenocytes (CD62L+; CD4+) and their total number (C) in mice treated with AAV-Il2rge3-8, AAV-MSCV-GFP, or no AAV (n = 16 per group) are shown. Data are presented as mean ± SD. **p < 0.01 (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). (D) Representative flow cytometry of naive CD8+ splenocytes (CD62L+; CD8+) and isotype control in AAV-Il2rg3-8-treated mice (AAV-MSCV-GFP-treated mice have no CD8+ cells) are shown. Spleen samples were obtained 32 weeks after transplant.

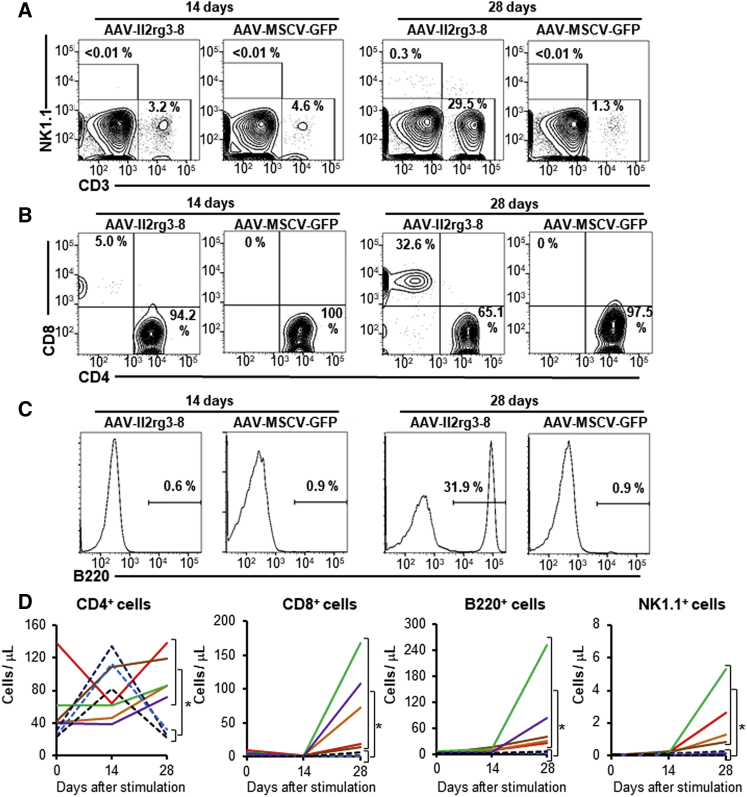

Immune responses in transplanted mice were assessed by injecting irradiated, allogeneic splenocytes from BALB/c mice (Figure 5). 28 days after immunization, AAV-Il2rg3-8-treated mice had a significant increase in peripheral blood CD8+ T cells, which in some mice approached wild-type levels (∼500 cells/μL; data not shown), as well as dramatic increases in circulating B and NK cells, which had previously been nearly undetectable. Immunization of untreated X-SCID mice did not increase the levels of these circulating cells. These results show that the gene-edited immune cells can respond to antigenic stimulation in vivo.

Figure 5.

Immune Cells Increase after Immunization with Allogeneic Cells

(A–C) Representative flow cytometry of CD3+ and NK1.1+ populations (A), CD4+ and CD8+ populations (B), and B220+ cells (C) in H-2Ddneg blood cells 14 and 28 days after primary immunization with BALB/c splenocytes. (D) The number of CD4+ cells, CD8+ cells, B220+ cells, and NK1.1+ cells in peripheral blood over time is shown. Each solid or dashed line represents a different AAV-Il2rg3-8-treated or X-SCID control mouse, respectively. *p < 0.05 (two-tailed t test).

Editing in Human Hematopoietic Cells

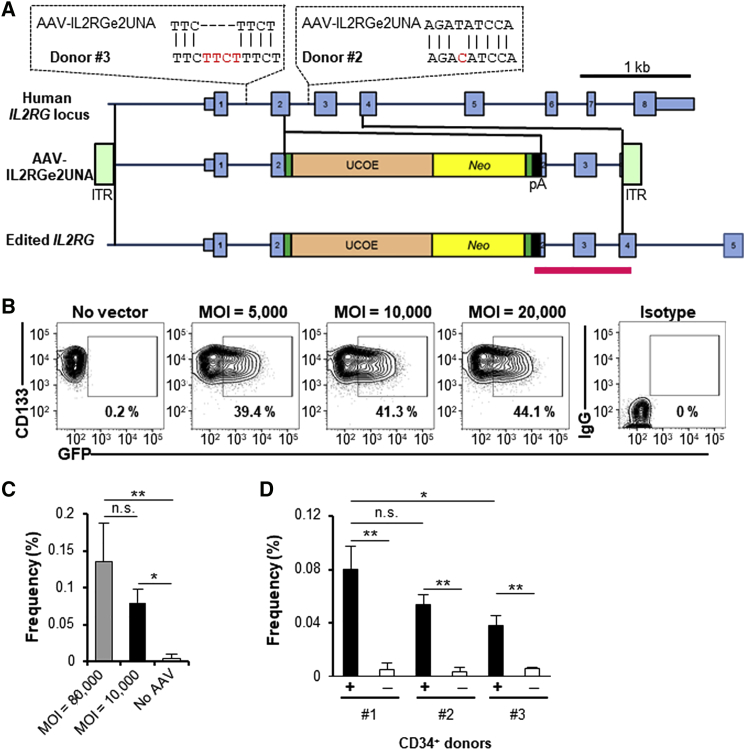

We previously developed vector AAV-IL2RGe2UNA (Figure 6A), which inserts a neomycin resistance cassette into exon 2 of human IL2RG, and used it to successfully edit the silent, X-linked IL2RG locus in ∼0.1% of infected human embryonic stem cells.27 Here, we measured the editing frequency in mobilized peripheral blood CD34+ cells from three different healthy male donors. First, we showed that over 40% of CD133+, CD34+ cells expressed GFP 2 days after infection with AAV-scMSCV-GFP at an MOI of 10,000 vector particles/cell (Figure 6B), confirming that human hematopoietic cells can be efficiently transduced by serotype 6 vectors, as was also observed in mouse cells. The IL2RG editing frequency was measured in CD133+, CD34+ cells from a healthy male donor (no. 1) by infection with AAV-IL2RGe2UNA and qPCR with primers inside and outside of the vector genome seven days later. This donor had no SNPs in the homology arm of the vector and produced gene editing frequencies of 0.06%–0.19% at an MOI of 10,000–80,000 (Figure 6C). Donors no. 2 and no. 3 had either a 1-bp mismatch in the right homology arm or a 4-bp insertion in the left homology arm relative to the vector sequence and had lower editing frequencies (Figure 6D), confirming the importance of perfectly matching vector and target loci SNPs.28

Figure 6.

IL2RG Editing in Human CD34+ Cells

(A) Map of the human IL2RG locus and AAV-IL2RGe2UNA editing vector. The IL2RG loci in CD34+ cell donors no. 2 and no. 3 have the indicated polymorphisms (SNP ID donor no. 2, rs11574625; donor no. 3, rs10693207). The red region indicates the qPCR amplicon. (B) GFP expression in vitro in AAV-scMSCV-GFP-transduced human CD34+ cells 2 days after infection is shown. (C) Editing frequencies in CD34+, CD133+ cells from donor no. 1 cultured for 7 days after infection with AAV-IL2RGe2UNA at the indicated MOIs (n = 3–5 for each condition) are shown. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). (D) Editing frequencies in CD34+, CD133+ cells from different donors 7 days after transduction with AAV-IL2RGe2UNA (black columns) or no vector control (white columns; n = 3–5 for each condition) are shown. Data are presented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 (two-way ANOVA).

Similar results were obtained with a vector designed to insert a GFP gene into the human EEF1A1 locus, which specifically produced GFP+ cells after gene editing, but not after episomal delivery or random integration (Figure S5). In this case, we were able to monitor the time course of gene editing without in vivo selection and found that GFP expression reached a peak 7–10 days after infection of CD34+ cells and that the editing frequency of primitive CD34+, CD38neg, CD90+ cells was similar to that of the bulk population of CD34+ cells.

Discussion

In summary, we have shown that nuclease-free AAV-mediated gene editing of X-SCID mouse BM cells can restore expression of Il2rg, which is the common subunit of the receptors for interleukin-2, -4, -7, -9, -15, and -21. These cytokines are required for normal T cell development and homeostasis, which allowed edited, Il2rg+ T cells to selectively proliferate in vivo, undergo TCR rearrangements, and produce naive CD4+ and CD8+ cells. Edited T cells persisted for more than 8 months in primary recipients and at least 4 more months in secondary recipients, demonstrating that editing had occurred in hematopoietic stem cells or long-lived lymphoid progenitors. Although minimal B and NK cell reconstitution was observed in primary recipients that had not been immunized, B cell numbers increased significantly in secondary recipients, possibly due to the transfer of edited, expanded cells in the primary recipient BM. Immunization of treated mice with allogeneic splenocytes led to dramatic increases in CD8+ cells, B cells, and NK cells, demonstrating that the edited cells can respond to antigenic stimuli and suggesting that immune cell numbers may be suppressed in the absence of normal exposure to antigens. Granulocytes did not increase in treated mice, and a modest increase in circulating monocytes was observed.

Whereas it is difficult to estimate the gene editing frequency that occurred before in vivo selection took place, the qPCR data from unselected, CD3neg splenocytes suggests that this value was between 0.1% and 1% of infected cells (Figure 2B). This was similar to the ∼0.1% IL2RG editing frequency we observed in human CD34+, CD133+ cells, as well as the nuclease-free, AAV-mediated editing frequencies observed in other primary cell types,9, 10, 11, 12 including experiments that produced therapeutic levels of factor IX after hepatocyte gene editing.29 However, an unusual feature we observed in hematopoietic cells was the low frequency of random AAV vector integration (∼0.1%), despite equivalent or higher editing frequencies and a majority of cells expressing the vector transgene transiently. In other cell types, the random integration frequency can approach 5%–10% of infected cells and gene editing frequencies are lower.30

Several groups have reported the use of site-specific nucleases to stimulate gene editing in hematopoietic cells,31 including editing of the human IL2RG locus.32 These studies have shown high rates of non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) at the cleavage site, somewhat lower rates of homology-directed repair (HDR) with a donor DNA template, and evidence for off-target cleavage.18, 32, 33, 34 Whereas the HDR assays used do not always distinguish between homologous recombination events and NHEJ-mediated donor DNA integration at nuclease cleavage sites, the sum of these processes occur at significantly higher frequencies (5% to over 50%) in primary hematopoietic cells than nuclease-free, AAV-mediated editing.18, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 However, HDR levels were lower (0.3%–3.5%) in the human SCID-repopulating cells (SRCs) than other hematopoietic populations,32, 33, 36 and SRCs can be modeled by the murine long-term repopulating cells we edited at 0.1%–1% frequencies in our experiments. This suggests that the nuclease provides a smaller advantage in these therapeutically relevant cells, perhaps because long-term repopulating cells are particularly sensitive to the methods used for nuclease delivery and/or exhibit a preference for NHEJ repair of nuclease cleavage sites rather than HDR,32, 33 which would not be factors in our experiments. Ultimately, any decrease in editing frequency caused by omitting the nuclease will have to be weighed against the increased accuracy of target site editing, lack of off-target cleavage sites, and reduced immunogenicity of our approach.

The X-SCID mouse model has been treated by gamma-retrovirus and lentivirus vectors expressing human or mouse Il2rg,37, 38, 39, 40 and similar human gene therapy trials have demonstrated therapeutic effects of gamma-retroviral vectors.4, 5, 41 Treatment with these non-specifically integrating vectors resulted in higher levels of T, B, and NK cells than observed in our study, presumably due to the lower frequency of gene editing in comparison to retroviral vector integration. However, we were able to demonstrate substantial increases in all these cell types after immunization with allogeneic cells. In addition, gene therapy with retroviral vectors has produced oncogenic vector insertions in both mouse and human X-SCID6, 42, 43 that remain a major concern for gene therapy. Whereas self-inactivating vectors that use internal promoter/enhancer elements to drive transgene expression may provide an improved safety profile,44, 45 there is still a theoretical possibility of neighboring oncogene activation. We did not observe leukemias or lymphomas in a total of 28 mice treated with AAV-Il2rg3-8 based on peripheral blood examinations and necropsies, including analyses of their spleens and mediastina. This is especially informative given that reconstitution of X-SCID mice with small numbers (∼5 × 103) of wild-type, Sca-1+ cells has been shown to promote donor-derived, thymic malignancies.46 Although AAV vectors can integrate non-specifically at existing chromosomal breaks,47 these are not elevated in the absence of nuclease treatment, and we observed low random integration rates in AAV-treated mice. Importantly, even if an AAV-Il2rg3-8 vector integrated near an oncogene, the lack of a vector promoter or enhancer should prevent oncogene overexpression. Additional safety features of gene editing are physiologic regulation of the edited Il2rg locus and the absence of a functional, vector-encoded Il2rg reading frame that could express from a randomly integrated provirus. This could prevent Il2rg overexpression, which may have a potentially oncogenic effect.48

Our results suggest that nuclease-free gene editing of X-SCID hematopoietic cells may be used to treat humans in the future. Unlike the mouse model that contains a neomycin-resistant transgene at the Il2rg locus, human X-SCID patients typically have point mutations or small insertions or deletions49 that could be corrected by AAV vectors containing wild-type chromosomal donor sequences instead of partial cDNAs, which would produce more accurate physiological regulation of IL2RG. Whereas the relatively low numbers of T, B, and NK cells we observed after gene editing could result in delayed immune reconstitution in comparison to more conventional IL2RG gene addition strategies, patients may be able to survive this period with supportive therapy and still achieve the long-term safety benefits of non-genotoxic, accurate gene editing. The editing frequencies we obtained are still too low to cure many other diseases, but several immunodeficiencies besides X-SCID also exhibit in vivo selection,50, 51 including ADA SCID,52 RAG1/2 deficiency,53 Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome,54 and Fanconi anemia.55 All of these diseases have been at least partly corrected by spontaneous reversion events, suggesting that even a single corrected cell might ultimately expand enough to provide some therapeutic effects. If nuclease-free editing can be further optimized, this approach could eventually be a safe and effective therapy for many hematologic diseases.

Materials and Methods

Mice

X-SCID mice (B6.129S4-Il2rgtm1Wjil/J), wild-type control mice (C57BL/6), and BALB/c mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Mice were housed in pathogen-free conditions with unrestricted access to sterilized food and drinking water. All experiments were performed in compliance with the University of Washington Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

AAV Vector Production

All targeting vector plasmids were constructed using routine molecular cloning methods and confirmed by DNA sequencing. The sequence of the Il2rg knockout chromosomal locus was determined by sequencing PCR-amplified genomic DNA from an X-SCID mouse. The mouse Il2rg coding sequence was amplified from cDNA synthesized from total RNA harvested from wild-type mouse peripheral blood. These sequences were assembled in an AAV vector backbone to produce pAAV-Il2rg3-8 plasmid. The control vector plasmids pAAV-scMSCV-GFP and pAAV-MSCV-GFP contain a GFP gene driven by a MSCV promoter and a human growth hormone polyadenylation signal. The pAAV-MSCV-GFP vector plasmid contains additional stuffer DNA to expand the genome size beyond 2.5 kb and force packaging of non-self-complementary vectors. The pAAV-IL2RGe2UNA plasmid was described previously27 and revised for this study by correcting a nucleotide polymorphism in the homology arm (reference SNP ID: rs10693207) so as to match CD34+ cell donor no. 1. The pAAV-EEF1A1e8-GFP-Puro vector plasmid contains human chromosomal DNA from the EEF1A1 locus (chromosome 6:73,515,752–73,521,032; hg38) with a P2A-GFP-F2A-Puro cassette inserted at chromosomal position 73,518,970 in an AAV vector backbone. AAV6 viral vectors were produced by calcium phosphate cotransfection of 293T cells with vector plasmids and the AAV6 capsid serotype helper plasmid pDGM656 with iodixanol step gradients and elution from a heparin column as previously described.57, 58 Vector titers were determined by Southern blots as genome-containing particles.

Transduction with AAV6 Vectors

Four days before harvesting BM cells, donor X-SCID mice were injected intraperitoneally with 5-fluorouracil (150 mg/kg; Fresenius Kabi, Lake Zurich, IL, USA). BM cells were harvested from the femurs and tibias of donors and transduced overnight at a MOI of 10,000 genome-containing particles/cell (except where indicated otherwise in Figure 1B) in 6-well plates (Corning, Corning, NY, USA) seeded with 2 × 106 cells per well. BM cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) containing 10% HyClone fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1% GlutaMax (Thermo Fisher Scientific), penicillin/streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 100 ng/mL recombinant mouse stem cell factor (SCF) (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA), 100 ng/mL recombinant mouse FMS-related tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (Flt3L) (Affymetrix, San Diego, CA, USA), and 10 ng/mL recombinant mouse thrombopoietin (TPO) (PeproTech). The media was changed the next day.

LSK cells were purified from 5-fluorouracil-treated male BM by the Lineage Cell Depletion Kit (Miltenyi Biotec, San Diego, CA, USA) and sorting using a BD FACSAria III (BD Pharmingen, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) after staining with allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated anti-CD117 antibody (2B8; BD Pharmingen) and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-Sca-1 antibody (D7; Miltenyi Biotec). LSK cells were cultured in StemSpan SPFM (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) with penicillin/streptomycin and the same concentrations of mouse SCF, Flt3L, and TPO described above. GFP expression from AAV-scMSCV-GFP was analyzed 2 days after infection by flow cytometry (BD FACSCanto II, BD Pharmingen) and staining with the BD Cell Viability kit (BD Pharmingen).

Human granulocyte colony-stimulating-factor-mobilized peripheral blood CD34+ cells were transduced overnight after one day of culture in 6-well plates seeded with 2 × 105 cells per well in StemSpan SPFM with penicillin/streptomycin, 100 ng/mL recombinant human SCF (Miltenyi Biotec), 100 ng/mL recombinant human Flt3L (Affymetrix), 10 ng/mL recombinant human TPO (Miltenyi Biotec), and AhR antagonist II (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The media was changed the next day and 4 days after transduction. GFP expression from AAV-scMSCV-GFP was analyzed 2 days after infection by flow cytometry and staining with the BD Cell Viability kit and PE-Vio770 conjugated anti-CD133/2 antibody (Miltenyi Biotec).

Transplantation

For primary transplantation, BM cells from 6-week-old male X-SCID mice were transduced overnight as described above with AAV-Il2rg3-8 or AAV-MSCV-GFP, and 3 × 106 BM cells were injected intravenously the next day into 6-week-old irradiated (800 cGy) female X-SCID recipients. For secondary transplantation, 2 × 107 whole BM cells from primary recipients 20 weeks post-transplant were injected intravenously into irradiated 6-week-old female mice. All transplant recipients were given enrofloxacin (Bayer, Leverkusen, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany) in the drinking water for 4 weeks after transplant.

Flow Cytometry

100 μL of peripheral blood was collected monthly by retro-orbital bleeding from transplant recipients. Red blood cells were lysed by ACK solution (150 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, and 1 mM ethylenediamine tetra-acetic acid) and the WBCs were counted after staining with Turk’s solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). For flow cytometry, 105 cells were suspended in PBS with 0.5% BSA and 2 mM EDTA and incubated with each antibody for 30 min at 4°C. The antibody concentrations were established by staining wild-type WBCs before each experiment. BM cells and splenocytes were stained similarly. The antibodies used were APC-conjugated anti-CD3 (17A2; BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), APC-cyanin 7 (Cy7)-conjugated anti-CD4 (L3T4, BD Pharmingen), Brilliant-Violet-510-conjugated anti-CD8a (53-6.7; BioLegend), APC-conjugated anti-CD11b (M1/70; BioLegend), PE-conjugated anti-CD45.2 (104; Affymetrix), PE-Cy7-conjugated anti-CD45.2 (104-2; Miltenyi Biotec), PE-conjugated anti-CD132 (TUGm2; BioLegend), PE-conjugated anti-CD62L (MEL-14; BioLegend), fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-IgD (11-26c; BD Pharmingen), PE-conjugated anti-Sca1 (D7; Miltenyi Biotec), PE-conjugated anti-NK1.1 (PK136; BioLegend), Brilliant-Violet-421-conjugated anti-B220 (RA3-6B2; BioLegend), FITC-conjugated H-2Dd (34-2-12; BioLegend), Brilliant-Violet-421-conjugated anti-human CD38 (HB-7; BioLegend), APC conjugated anti-human CD90 (5E10; BioLegend), PE conjugated anti-human CD34 (563; BD Pharmingen), and fluorescence-conjugated isotype controls (all BioLegend). Live, stained cells were analyzed by using the BD Cell Viability kit on a FACSCanto II flow cytometer.

qPCR and Sequencing

Genomic DNA was harvested from mouse BM cells, CD3+ and CD3neg splenocytes, peripheral blood WBCs, and human CD34+ cells by using the QIAamp DNA Micro Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). The CD3+ and CD3neg splenocytes were collected by staining with APC-conjugated anti-CD3 body and PE-conjugated anti-CD45.2 and sorting on a BD FACSAria III. qPCR was performed with the GoTaq Probe qPCR Master Mix (Promega) on a StepOnePlus real-time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Total mouse DNA amounts were determined by amplifying the Bcl2 gene. To confirm that editing occurred, we amplified an edited allele-specific product from the genomic DNA of CD3+ splenocytes isolated from AAV-Il2rg3-8-treated mice with Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) on a C1000 Touch Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and then cloned and sequenced the gel-isolated product. We also prepared total RNA from the CD3+ splenocytes of AAV-Il2rg3-8-treated mice with the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN), synthesized cDNA with the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Thermo Fisher Scientific), amplified an edited allele-specific cDNA, and sequenced the product. For analyzing editing by AAV-IL2RGe2UNA, we used a linearized qPCR control plasmid that contained the edited allele sequence diluted in genomic DNA from untransduced CD34+ cells as standards. Total human DNA amounts were determined by amplifying the GAPDH gene. The primers, probes, and conditions used are shown in Table S1.

TCR Repertoire Analysis

Variable (V) β chain repertoires in complementary determining region 3 were analyzed by preparing total RNA from CD3+ splenocytes with the RNeasy Mini Kit and synthesizing cDNA with the iScript Select cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad). A first-step PCR was performed using a specific primer for the constant region of the TCR β chain (Cβ) in combination with 21 V gene-segment-specific primers, and the products underwent a second PCR using an internal fluorescein (FAM)-labeled Cβ-specific primer. Primer sequences and PCR conditions were based on a previous report.59 FAM-labeled products were analyzed on a DNA sequencer by the Genomics Facility of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (Seattle, WA, USA), and the data were analyzed using Peak Scanner Software (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Immunization with Splenocytes

Splenocytes were harvested from 8- to 12-week-old H-2Dd+ BALB/c mice and irradiated (30 Gy). Then, 5 × 107 cells were injected intraperitoneally into AAV-Il2rg3-8-treated mice 32 weeks after transplant or X-SCID mice. 2 weeks later, 100 μL of peripheral blood was collected by retro-orbital bleeding and 105 cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Host blood cell populations were analyzed in H-2Ddneg CD45.2+ living cells. On the next day, 5 × 107 irradiated BALB/c splenocytes were injected again, and host blood cell populations were analyzed again 2 weeks later.

Statistical Analysis

Sample sizes were determined based on pilot studies and analysis of statistical significance. Randomization and blind tests were not used for animal studies. Animals were not excluded from the analysis. Values are presented as the mean ± SD, and p value < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed by the unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test for pairwise comparisons or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison or two-way ANOVA post-test for more than three groups using Prism 7 software (Graph Pad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Author Contributions

T.H., L.B.L., and D.W.R. designed this study. T.H., L.B.L., and D.W.R. designed and constructed AAV vector plasmids. L.B.L. and R.K.H. made AAV vector stocks. T.H. and S.E.F. maintained mice and performed animal experiments. T.H. performed all other experiments. T.H., L.B.L., and D.W.R. wrote the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

D.R. holds equity in Universal Cells. The other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank E. Jensen (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center [FHCRC], Seattle, WA) for analyzing TCR fragment lengths; T.L. Lovelace, M.R. Gerace, S. Oliver, D.J. Yadock, C.T. Nguyen, and S. Heimfeld (FHCRC) for providing human CD34+ cells; D. Prunkard (Pathology Flow Cytometry Core Facility in UW) for technical assistance with flow cytometry; University of Washington animal facility staff and veterinarians; and Raisa Stolitenko for technical assistance. We also thank Russell lab members, F. Haeseleer, C.A. Francis, G.G. Gornalusse, D. Dalwadi, and A. Colunga for helpful discussions. T.H. was supported by postdoctoral fellowship from Uehara Memorial Foundation (Japan). This work was supported in part by grants from the NIH to D.W.R. (DK55759).

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes five figures and one table and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.02.028.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Rochman Y., Spolski R., Leonard W.J. New insights into the regulation of T cells by gamma(c) family cytokines. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009;9:480–490. doi: 10.1038/nri2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noguchi M., Yi H., Rosenblatt H.M., Filipovich A.H., Adelstein S., Modi W.S., McBride O.W., Leonard W.J. Interleukin-2 receptor gamma chain mutation results in X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency in humans. Cell. 1993;73:147–157. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90167-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puck J.M., Deschênes S.M., Porter J.C., Dutra A.S., Brown C.J., Willard H.F., Henthorn P.S. The interleukin-2 receptor gamma chain maps to Xq13.1 and is mutated in X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency, SCIDX1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1993;2:1099–1104. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.8.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavazzana-Calvo M., Hacein-Bey S., de Saint Basile G., Gross F., Yvon E., Nusbaum P., Selz F., Hue C., Certain S., Casanova J.L. Gene therapy of human severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID)-X1 disease. Science. 2000;288:669–672. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5466.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaspar H.B., Parsley K.L., Howe S., King D., Gilmour K.C., Sinclair J., Brouns G., Schmidt M., Von Kalle C., Barington T. Gene therapy of X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency by use of a pseudotyped gammaretroviral vector. Lancet. 2004;364:2181–2187. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17590-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hacein-Bey-Abina S., Von Kalle C., Schmidt M., McCormack M.P., Wulffraat N., Leboulch P., Lim A., Osborne C.S., Pawliuk R., Morillon E. LMO2-associated clonal T cell proliferation in two patients after gene therapy for SCID-X1. Science. 2003;302:415–419. doi: 10.1126/science.1088547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braun C.J., Boztug K., Paruzynski A., Witzel M., Schwarzer A., Rothe M., Modlich U., Beier R., Göhring G., Steinemann D. Gene therapy for Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome--long-term efficacy and genotoxicity. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014;6:227ra33. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stein S., Ott M.G., Schultze-Strasser S., Jauch A., Burwinkel B., Kinner A., Schmidt M., Krämer A., Schwäble J., Glimm H. Genomic instability and myelodysplasia with monosomy 7 consequent to EVI1 activation after gene therapy for chronic granulomatous disease. Nat. Med. 2010;16:198–204. doi: 10.1038/nm.2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Russell D.W., Hirata R.K. Human gene targeting by viral vectors. Nat. Genet. 1998;18:325–330. doi: 10.1038/ng0498-325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chamberlain J.R., Schwarze U., Wang P.R., Hirata R.K., Hankenson K.D., Pace J.M., Underwood R.A., Song K.M., Sussman M., Byers P.H., Russell D.W. Gene targeting in stem cells from individuals with osteogenesis imperfecta. Science. 2004;303:1198–1201. doi: 10.1126/science.1088757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chamberlain J.R., Deyle D.R., Schwarze U., Wang P., Hirata R.K., Li Y., Byers P.H., Russell D.W. Gene targeting of mutant COL1A2 alleles in mesenchymal stem cells from individuals with osteogenesis imperfecta. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:187–193. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan I.F., Hirata R.K., Wang P.R., Li Y., Kho J., Nelson A., Huo Y., Zavaljevski M., Ware C., Russell D.W. Engineering of human pluripotent stem cells by AAV-mediated gene targeting. Mol. Ther. 2010;18:1192–1199. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deyle D.R., Hansen R.S., Cornea A.M., Li L.B., Burt A.A., Alexander I.E., Sandstrom R.S., Stamatoyannopoulos J.A., Wei C.L., Russell D.W. A genome-wide map of adeno-associated virus-mediated human gene targeting. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014;21:969–975. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hendrie P.C., Hirata R.K., Russell D.W. Chromosomal integration and homologous gene targeting by replication-incompetent vectors based on the autonomous parvovirus minute virus of mice. J. Virol. 2003;77:13136–13145. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.24.13136-13145.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirata R.K., Russell D.W. Design and packaging of adeno-associated virus gene targeting vectors. J. Virol. 2000;74:4612–4620. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.10.4612-4620.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trobridge G., Hirata R.K., Russell D.W. Gene targeting by adeno-associated virus vectors is cell-cycle dependent. Hum. Gene Ther. 2005;16:522–526. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inoue N., Hirata R.K., Russell D.W. High-fidelity correction of mutations at multiple chromosomal positions by adeno-associated virus vectors. J. Virol. 1999;73:7376–7380. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7376-7380.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang J., Exline C.M., DeClercq J.J., Llewellyn G.N., Hayward S.B., Li P.W., Shivak D.A., Surosky R.T., Gregory P.D., Holmes M.C., Cannon P.M. Homology-driven genome editing in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells using ZFN mRNA and AAV6 donors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:1256–1263. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao X., Shores E.W., Hu-Li J., Anver M.R., Kelsall B.L., Russell S.M., Drago J., Noguchi M., Grinberg A., Bloom E.T. Defective lymphoid development in mice lacking expression of the common cytokine receptor γ chain. Immunity. 1995;2:223–238. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rutledge E.A., Halbert C.L., Russell D.W. Infectious clones and vectors derived from adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotypes other than AAV type 2. J. Virol. 1998;72:309–319. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.309-319.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ellis B.L., Hirsch M.L., Barker J.C., Connelly J.P., Steininger R.J., 3rd, Porteus M.H. A survey of ex vivo/in vitro transduction efficiency of mammalian primary cells and cell lines with Nine natural adeno-associated virus (AAV1-9) and one engineered adeno-associated virus serotype. Virol. J. 2013;10:74. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei C., Zeff R., Goldschneider I. Murine pro-B cells require IL-7 and its receptor complex to up-regulate IL-7R alpha, terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase, and c mu expression. J. Immunol. 2000;164:1961–1970. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meazza R., Azzarone B., Orengo A.M., Ferrini S. Role of common-gamma chain cytokines in NK cell development and function: perspectives for immunotherapy. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011;2011:861920. doi: 10.1155/2011/861920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller D.G., Trobridge G.D., Petek L.M., Jacobs M.A., Kaul R., Russell D.W. Large-scale analysis of adeno-associated virus vector integration sites in normal human cells. J. Virol. 2005;79:11434–11442. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.17.11434-11442.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakai H., Wu X., Fuess S., Storm T.A., Munroe D., Montini E., Burgess S.M., Grompe M., Kay M.A. Large-scale molecular characterization of adeno-associated virus vector integration in mouse liver. J. Virol. 2005;79:3606–3614. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3606-3614.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen K., Cerutti A. New insights into the enigma of immunoglobulin D. Immunol. Rev. 2010;237:160–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00929.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li L.B., Ma C., Awong G., Kennedy M., Gornalusse G., Keller G., Kaufman D.S., Russell D.W. Silent IL2RG gene editing in human pluripotent stem cells. Mol. Ther. 2016;24:582–591. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deyle D.R., Li L.B., Ren G., Russell D.W. The effects of polymorphisms on human gene targeting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:3119–3124. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barzel A., Paulk N.K., Shi Y., Huang Y., Chu K., Zhang F., Valdmanis P.N., Spector L.P., Porteus M.H., Gaensler K.M., Kay M.A. Promoterless gene targeting without nucleases ameliorates haemophilia B in mice. Nature. 2015;517:360–364. doi: 10.1038/nature13864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirata R., Chamberlain J., Dong R., Russell D.W. Targeted transgene insertion into human chromosomes by adeno-associated virus vectors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002;20:735–738. doi: 10.1038/nbt0702-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu K.R., Natanson H., Dunbar C.E. Gene editing of human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells: promise and potential hurdles. Hum. Gene Ther. 2016;27:729–740. doi: 10.1089/hum.2016.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Genovese P., Schiroli G., Escobar G., Tomaso T.D., Firrito C., Calabria A., Moi D., Mazzieri R., Bonini C., Holmes M.C. Targeted genome editing in human repopulating haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2014;510:235–240. doi: 10.1038/nature13420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoban M.D., Cost G.J., Mendel M.C., Romero Z., Kaufman M.L., Joglekar A.V., Ho M., Lumaquin D., Gray D., Lill G.R. Correction of the sickle cell disease mutation in human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Blood. 2015;125:2597–2604. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-12-615948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoban M.D., Lumaquin D., Kuo C.Y., Romero Z., Long J., Ho M., Young C.S., Mojadidi M., Fitz-Gibbon S., Cooper A.R. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated correction of the sickle mutation in human CD34+ cells. Mol. Ther. 2016;24:1561–1569. doi: 10.1038/mt.2016.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sather B.D., Romano Ibarra G.S., Sommer K., Curinga G., Hale M., Khan I.F., Singh S., Song Y., Gwiazda K., Sahni J. Efficient modification of CCR5 in primary human hematopoietic cells using a megaTAL nuclease and AAV donor template. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015;7:307ra156. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac5530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dever D.P., Bak R.O., Reinisch A., Camarena J., Washington G., Nicolas C.E., Pavel-Dinu M., Saxena N., Wilkens A.B., Mantri S. CRISPR/Cas9 β-globin gene targeting in human haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2016;539:384–389. doi: 10.1038/nature20134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soudais C., Shiho T., Sharara L.I., Guy-Grand D., Taniguchi T., Fischer A., Di Santo J.P. Stable and functional lymphoid reconstitution of common cytokine receptor γ chain deficient mice by retroviral-mediated gene transfer. Blood. 2000;95:3071–3077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lo M., Bloom M.L., Imada K., Berg M., Bollenbacher J.M., Bloom E.T., Kelsall B.L., Leonard W.J. Restoration of lymphoid populations in a murine model of X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency by a gene-therapy approach. Blood. 1999;94:3027–3036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Otsu M., Anderson S.M., Bodine D.M., Puck J.M., O’Shea J.J., Candotti F. Lymphoid development and function in X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency mice after stem cell gene therapy. Mol. Ther. 2000;1:145–153. doi: 10.1006/mthe.1999.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huston M.W., van Til N.P., Visser T.P., Arshad S., Brugman M.H., Cattoglio C., Nowrouzi A., Li Y., Schambach A., Schmidt M. Correction of murine SCID-X1 by lentiviral gene therapy using a codon-optimized IL2RG gene and minimal pretransplant conditioning. Mol. Ther. 2011;19:1867–1877. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hacein-Bey-Abina S., Le Deist F., Carlier F., Bouneaud C., Hue C., De Villartay J.P., Thrasher A.J., Wulffraat N., Sorensen R., Dupuis-Girod S. Sustained correction of X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency by ex vivo gene therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;346:1185–1193. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Woods N.B., Bottero V., Schmidt M., von Kalle C., Verma I.M. Gene therapy: therapeutic gene causing lymphoma. Nature. 2006;440:1123. doi: 10.1038/4401123a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hacein-Bey-Abina S., Garrigue A., Wang G.P., Soulier J., Lim A., Morillon E., Clappier E., Caccavelli L., Delabesse E., Beldjord K. Insertional oncogenesis in 4 patients after retrovirus-mediated gene therapy of SCID-X1. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:3132–3142. doi: 10.1172/JCI35700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thornhill S.I., Schambach A., Howe S.J., Ulaganathan M., Grassman E., Williams D., Schiedlmeier B., Sebire N.J., Gaspar H.B., Kinnon C. Self-inactivating gammaretroviral vectors for gene therapy of X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:590–598. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hacein-Bey-Abina S., Pai S.-Y., Gaspar H.B., Armant M., Berry C.C., Blanche S., Bleesing J., Blondeau J., de Boer H., Buckland K.F. A modified γ-retrovirus vector for X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:1407–1417. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1404588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ginn S.L., Hallwirth C.V., Liao S.H.Y., Teber E.T., Arthur J.W., Wu J., Lee H.C., Tay S.S., Hu M., Reddel R.R. Limiting thymic precursor supply increases the risk of lymphoid malignancy in murine X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2017;6:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2016.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miller D.G., Petek L.M., Russell D.W. Adeno-associated virus vectors integrate at chromosome breakage sites. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:767–773. doi: 10.1038/ng1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pike-Overzet K., de Ridder D., Weerkamp F., Baert M.R., Verstegen M.M., Brugman M.H., Howe S.J., Reinders M.J., Thrasher A.J., Wagemaker G. Gene therapy: is IL2RG oncogenic in T-cell development? Nature. 2006;443:E5. doi: 10.1038/nature05218. discussion E6–E7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Puck J.M., Pepper A.E., Henthorn P.S., Candotti F., Isakov J., Whitwam T., Conley M.E., Fischer R.E., Rosenblatt H.M., Small T.N., Buckley R.H. Mutation analysis of IL2RG in human X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency. Blood. 1997;89:1968–1977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stephan V., Wahn V., Le Deist F., Dirksen U., Broker B., Müller-Fleckenstein I., Horneff G., Schroten H., Fischer A., de Saint Basile G. Atypical X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency due to possible spontaneous reversion of the genetic defect in T cells. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996;335:1563–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199611213352104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bousso P., Wahn V., Douagi I., Horneff G., Pannetier C., Le Deist F., Zepp F., Niehues T., Kourilsky P., Fischer A., de Saint Basile G. Diversity, functionality, and stability of the T cell repertoire derived in vivo from a single human T cell precursor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:274–278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hirschhorn R., Yang D.R., Puck J.M., Huie M.L., Jiang C.K., Kurlandsky L.E. Spontaneous in vivo reversion to normal of an inherited mutation in a patient with adenosine deaminase deficiency. Nat. Genet. 1996;13:290–295. doi: 10.1038/ng0796-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wada T., Toma T., Okamoto H., Kasahara Y., Koizumi S., Agematsu K., Kimura H., Shimada A., Hayashi Y., Kato M., Yachie A. Oligoclonal expansion of T lymphocytes with multiple second-site mutations leads to Omenn syndrome in a patient with RAG1-deficient severe combined immunodeficiency. Blood. 2005;106:2099–2101. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-0936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ariga T., Kondoh T., Yamaguchi K., Yamada M., Sasaki S., Nelson D.L., Ikeda H., Kobayashi K., Moriuchi H., Sakiyama Y. Spontaneous in vivo reversion of an inherited mutation in the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. J. Immunol. 2001;166:5245–5249. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.8.5245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Waisfisz Q., Morgan N.V., Savino M., de Winter J.P., van Berkel C.G., Hoatlin M.E., Ianzano L., Gibson R.A., Arwert F., Savoia A. Spontaneous functional correction of homozygous fanconi anaemia alleles reveals novel mechanistic basis for reverse mosaicism. Nat. Genet. 1999;22:379–383. doi: 10.1038/11956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gregorevic P., Blankinship M.J., Allen J.M., Crawford R.W., Meuse L., Miller D.G., Russell D.W., Chamberlain J.S. Systemic delivery of genes to striated muscles using adeno-associated viral vectors. Nat. Med. 2004;10:828–834. doi: 10.1038/nm1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zolotukhin S., Byrne B.J., Mason E., Zolotukhin I., Potter M., Chesnut K., Summerford C., Samulski R.J., Muzyczka N. Recombinant adeno-associated virus purification using novel methods improves infectious titer and yield. Gene Ther. 1999;6:973–985. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khan I.F., Hirata R.K., Russell D.W. AAV-mediated gene targeting methods for human cells. Nat. Protoc. 2011;6:482–501. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pannetier C., Cochet M., Darche S., Casrouge A., Zöller M., Kourilsky P. The sizes of the CDR3 hypervariable regions of the murine T-cell receptor β chains vary as a function of the recombined germ-line segments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:4319–4323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.4319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.