Abstract

Deafness is commonly caused by the irreversible loss of mammalian cochlear hair cells (HCs) due to noise trauma, toxins, or infections. We previously demonstrated that small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) directed against the Notch pathway gene, hairy and enhancer of split 1 (Hes1), encapsulated within biocompatible poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles (PLGA NPs) could regenerate HCs within ototoxin-ablated murine organotypic cultures. In the present study, we delivered this sustained-release formulation of Hes1 siRNA (siHes1) into the cochleae of noise-injured adult guinea pigs. Auditory functional recovery was measured by serial auditory brainstem responses over a nine-week follow-up period, and HC regeneration was evaluated by immunohistological evaluations and scanning electron microscopy. Significant HC restoration and hearing recovery were observed across a broad tonotopic range in ears treated with siHes1 NPs, beginning at three weeks and extending out to nine weeks post-treatment. Moreover, both ectopic and immature HCs were uniquely observed in noise-injured cochleae treated with siHes1 NPs, consistent with de novo HC production. Our results indicate that durable cochlear HCs were regenerated and promoted significant hearing recovery in adult guinea pigs through reversible modulation of Hes1 expression. Therefore, PLGA-NP-mediated delivery of siHes1 to the cochlea represents a promising pharmacologic approach to regenerate functional and sustainable mammalian HCs in vivo.

Keywords: hair cell regeneration, siRNA, nanoparticle, Notch pathway, acute acoustic trauma, cochlea, guinea pig

In this issue of Molecular Therapy, Du et al. (2018) used biocompatible nanoparticles encapsulating siRNA molecules targeting the Notch pathway effector, Hes1, to induce cochlear hair cell regeneration in a live-animal model of noise-induced hearing loss. Their electrophysiological and histological evaluations demonstrate significant, treatment-specific hair cell restoration and hearing recovery.

Introduction

Deafness and loss of balance are commonly caused by a loss of sensory hair cells (HCs) due to toxins, infections, noise and/or blast trauma, aging, and other factors.1, 2 Once lost, cochlear HCs in mammals do not spontaneously regenerate, which can result in permanent hearing impairments, as HC attrition accumulates over time or is acutely manifested following a severe acoustic or ototoxic trauma.3, 4, 5

In the mammalian cochlea, HCs and supporting cells (SCs), which provide trophic, structural, and functional support to HCs, are arranged in an alternating mosaic-like pattern, in which adjacent HCs do not directly contact one another. This spatial specificity is established during embryonic development and is maintained postnatally through lateral inhibition via active Notch signaling. Notch is a cell surface receptor protein that, when activated, upregulates downstream effector molecules, such as hairy and enhancer of split-1 and 5 (Hes1 and Hes5), which in turn inhibit the expression of proneural basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors, such as atonal homolog 1 (Atoh1).6, 7 HCs and SCs arise from a common prosensory epithelial cell lineage,8 and Atoh1 expression is critical for initiating the transcriptional cascade necessary for HC differentiation.9, 10 Thus, lateral inhibition prevents SCs from transdifferentiating into HCs through active Notch signaling that is maintained via direct contact with Notch ligands expressed on the surfaces of adjacent HCs or neighboring SCs.6, 7 Indeed, in nonmammalian vertebrates, SCs spontaneously regenerate into new HCs through both mitotic and non-mitotic (transdifferentiation) mechanisms.11, 12, 13, 14 Studies have shown that this process can be opposed or reversed by Notch pathway activation.15, 16 Conversely, other in vivo studies indicate that, in mammals, either decreasing Notch signaling within the organ of Corti (OC) or increasing Atoh1 expression is sufficient to generate new HCs through direct transdifferentiation of pre-existing SCs.17, 18, 19, 20, 21

Previous studies have demonstrated that, in addition to maintaining lateral inhibition, Notch pathway gene expression is increased in mammalian cochleae and vestibular end organs (i.e., utricles and saccules) after acoustic trauma or ototoxic insults.17, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 In the adult guinea pig, ototoxic damage to the cochlea has been shown to result in elevated Hes1 and Hes5 expression in concert with increased expression of the Notch1 receptor and ligands, such as Jagged1, among surviving SCs.22 Acoustic traumas have also been shown to induce upregulation of Hes1 and Hes5 mRNA in the OC.20, 27 Based on its central role in promoting and maintaining the SC phenotype, both elevated and homeostatic Notch-dependent Hes1 expression among surviving SCs may actively oppose an intrinsic HC regenerative program.22, 28, 29 Consistent with these reports, results from our previous in vitro studies and other labs have indicated that targeted and reversible silencing of Hes1 expression is sufficient to promote pro-transdifferentiative signaling in the postnatal murine cochlea.23, 24, 30 In the present study, we delivered biocompatible poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles (NPs) containing Hes1 small interfering RNA (siRNA) payloads into the cochleae of adult guinea pigs to evaluate whether this refined pharmacological approach could also induce cochlear HC regeneration and hearing recovery in vivo in adult animals that had been exposed to a deafening noise trauma.

Results

Experimental Design

Prior to the deafening noise exposure, the young adult guinea pigs employed in this study exhibited normal baseline auditory brainstem response (ABR) thresholds of 5–30 dB sound press level (SPL) at the 2-, 4-, 8-, and 16-kHz test frequencies (all p > 0.05). However, due to large inter-animal variability to noise exposure in guinea pigs,31 some guinea pigs did not exhibit sufficient hearing loss at 24 hr after the acoustic trauma as measured by ABR. To limit the influence of this inter-animal variation on the objective assessment of hearing recovery after treatment, animals that did not present with bilateral ABR thresholds greater than 80 dB SPL at any frequency at 24 hr after noise exposure (125 dB SPL centered at 4 kHz for three hours) were excluded from the study. After application of this exclusion criterion, deafened guinea pigs were randomly assigned to one of two cohorts designated for either sham (scrambled siRNA [scRNA]) or Hes1 siRNA (siHes1) NP treatment. The average pre-treatment threshold shifts observed in the two groups for each test frequency were statistically identical, except at 2 kHz, where significantly greater hearing loss was observed in the siHes1 NP treatment group (p < 0.01; Figure 1A).

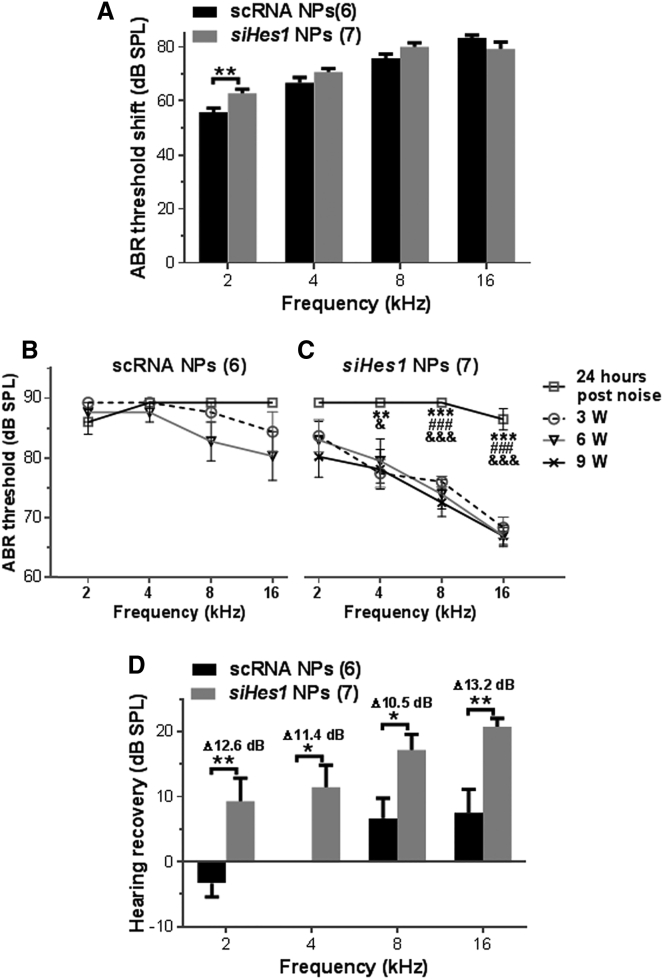

Figure 1.

siHes1 NP Treatment Restores Hearing Function in Noise-Deafened Ears

(A) Pre-treatment hearing threshold shifts in the scRNA NP and siHes1 NP cohorts at 24 hr after a deafening noise exposure (125 dB SPL centered at 4 kHz for 3 hr). Statistically identical threshold shifts at each test frequency were recorded in the two groups, except at 2 kHz, where significantly greater hearing loss was observed in the siHes1 NP cohort (**p < 0.01). (B) No significant hearing improvement was observed in noise-deafened guinea pigs treated with scRNA NPs at any time point after treatment (all p > 0.05). (C) In comparison to pre-treatment ABR thresholds, significant hearing improvement was observed at all time points (3, 6, and 9 weeks after treatment) in siHes1-NP-treated ears across the 4- to 16-kHz frequency range. ***p < 0.001 versus 3 weeks after treatment; ###p < 0.001 versus 6 weeks after treatment; &p < 0.05 and &&&p <0.001 versus 9 weeks after treatment. (D) Significant hearing improvement, as measured by ABR threshold recovery, was observed in the siHes1 NP treatment group at all frequencies tested compared to the scRNA NP treatment group (*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01). Δ dB indicates frequency-specific hearing improvement in the siHes1 NP treatment group compared to the scRNA NP treatment group. Numbers in parentheses represent the number of ears evaluated in each group. Errors bars represent SEM.

Hearing Restoration following siHes1 NP Treatment

Sham (scRNA) or therapeutic (siHes1) NP treatment was initiated via unilateral intracochlear infusion by mini-osmotic pumps at 72 hr post-deafening. Twenty-four hours later, the treatment was terminated upon surgical extraction of the pumps. Serial ABR threshold measurements were conducted at three, six, and nine weeks after treatment in all animals. In the scRNA-NP-treated ears, thresholds remained above 85 dB SPL at all test frequencies at three weeks post-treatment. At subsequent test intervals of six and nine weeks post-treatment, marginally lower thresholds (4 or 5 dB) were recorded at 8 and 16 kHz, whereas no improvements in auditory function were recorded at 2 and 4 kHz (Figure 1B; all p > 0.05). These results revealed that no statistically significant hearing recovery occurred in the sham-NP-treated ears, indicating that the acoustic trauma induced both profound and permanent deafness.

In contrast to the scRNA-NP-treated cohort, statistically significant hearing recovery was observed among ears infused with siHes1 NPs across test frequencies of 4–16 kHz, beginning at three weeks post-treatment and extending out to the terminal sampling interval of nine weeks post-treatment (p < 0.05, 0.01, or 0.001; Figure 1C). Although the in-group hearing recovery at 2 kHz was not calculated to be statistically significant, an average ABR threshold improvement of 5.7 dB SPL was measured at this frequency at three weeks post-treatment, which increased to 9.3 dB SPL at the terminal nine-week recording interval, indicative of ongoing functional recovery at this tonotopic position. Modest progressive recovery was also measured across the experimental time course at 8 kHz in the siHes1-NP-treated cohort, whereas maximal hearing recovery at the 4- and 16-kHz test frequencies were achieved at three weeks post-treatment (Figure 1C). It should be noted that, based on the parameters of our noise-exposure paradigm, the 4-kHz tonotopic region of the cochlea likely served as the epicenter of trauma (see Figures 1B and 2).32, 33

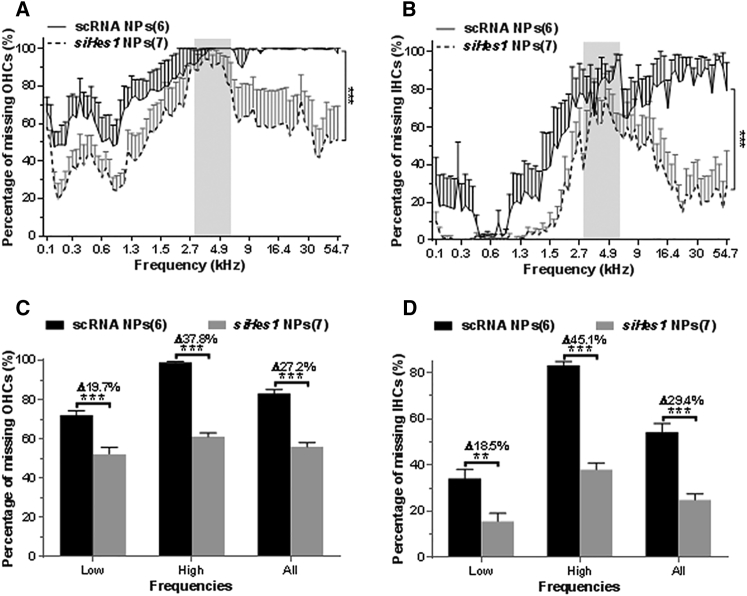

Figure 2.

siHes1 NP Treatment Restores HC Numbers in the OCs of Noise-Deafened Guinea Pigs

(A and B) The average number of missing OHCs (A) and IHCs (B) along the length of the basilar membrane in surface preparations of cochleae collected at 9 weeks after scRNA or siHes1 NP treatment is depicted as cytocochleograms. Shaded areas in (A) and (B) indicate the frequency range of the 4-kHz octave band noise exposure. Almost 100% of OHCs were eliminated in the tonotopic frequency positions ranging from 4.9 to 54.7 kHz in the scRNA group (A), whereas approximately 80% of IHCs were eliminated across this frequency region (B). Significantly less overall HC loss was observed in the siHes1 NP treatment group compared to the scRNA treatment group (***p < 0.001 in A and B). (C and D) IHC (C) and OHC (D) recovery in the low-frequency region (low in C and D; 0.1–4.6 kHz), the high-frequency region (high in C and D; 4.9–54.7 kHz), and among all frequency regions (all in C and D; 0.1–54.7 kHz) were calculated and statistically analyzed. Significant OHC and IHC recovery was observed in the siHes1 NP treatment group across all tonotopic frequency regions and within each of the two frequency subgroups compared to the scRNA group (**p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001). Δ dB indicates HC recovery in the siHes1 NP group compared to the scRNA NP group within each frequency range. Numbers in parentheses represent the number of ears evaluated in each group. Errors bars represent SEM.

Average post-deafening ABR threshold recoveries (Δ dB) were calculated by subtracting ABR threshold recovery (i.e., [ABR threshold at 24 hr after noise exposure] − [ABR threshold at 9 weeks after treatment]) in the scRNA-NP-treated ears from ABR threshold recovery in the siHes1-NP-treated ears at each frequency at the terminal, nine-week, post-treatment sampling interval. From this analysis, the average threshold recovery across all four test frequencies in the siHes1-NP-treatment group was 14.64 dB SPL, whereas a recovery of only 2.71 dB SPL was achieved in the scRNA group (p < 0.001). In the siHes1-NP-treated group, average threshold recoveries exhibited a basal-to-apical gradient of improvement, such that, at 2, 4, 8, and 16 kHz, the threshold recoveries were 9.29, 11.43, 17.14, and 20.71 dB SPL, respectively. No such gradient effect was observed in the sham (scRNA)-NP-treated cohort, in which the corresponding average frequency-dependent recoveries in treated ears were −3.33, 0, 6.67, and 7.5 dB. These results translated to statistically significant siHes1-NP-specific hearing recovery at each test frequency, with an average improvement of greater than 10 dB relative to scRNA NP control-treated ears (p < 0.05 or 0.01; Figure 1D).

siHes1 NPs Restore Inner and Outer HC Populations in Noise-Deafened Cochleae

HC counts were conducted along the basilar membranes among cochlea harvested from the scRNA NP and siHes1 NP cohorts at nine weeks post-treatment. Cytocochleograms showing the average percentage of missing myosin VIIa-positive outer HCs (OHCs) and inner HCs (IHCs) between the two treatment groups are depicted in Figures 2A and 2B, respectively. As predicted, the noise injury caused pervasive HC loss throughout the cochlea. In sham (scRNA)-NP-treated ears, the majority of OHCs (98.9%) and IHCs (83.2%) were completely ablated in the basal and second turns (tonotopic frequency ranges of 4.9–54.7 kHz) of the OC, whereas the HC quantification across lower tonotopic frequency positions (0.1–4.6 kHz) revealed a reduced, albeit pronounced, incidence of OHC (72.0%) and IHC (34.1%) loss. In total, the average percentages of missing OHCs and IHCs in scRNA-treated cochleae were 83.1% and 54.3%, respectively.

In noise-deafened cochleae treated with siHes1 NPs, the average percentage of missing OHCs and IHCs (55.9% and 24.9%, respectively) at nine weeks post-treatment was significantly reduced across the entire span of the OC (all p < 0.001 compared to the scRNA-NP-treated group; Figures 2A and 2B). Regionalized siHes1-NP-specific HC restoration was statistically analyzed and is graphically depicted in Figures 2C and 2D. From this analysis, statistically significant increases in average OHC numbers (Δ27.2% or approximately 1,960 OHCs/cochlea) were observed across all (low + high) tonotopic positions in siHes1-NP-infused cochleae relative to scRNA NP controls. Although the high-frequency region (4.9–54.7 kHz) of the OC presented with a greater overall degree (p < 0.001) of treatment-specific OHC restoration (Δ37.8% or approximately 1,123 OHCs/cochlea) than the more apical, low-frequency region (0.1–4.6 kHz, Δ19.7%, or approximately 835 OHCs/cochlea), both areas experienced similar relative gains in total OHCs (∼1.6-fold versus ∼1.4-fold in high- and low-frequency regions, respectively; Figure 2C).

Quantitative evaluation of IHC numbers in siHes1-NP-treated ears also demonstrated an overall treatment-specific restoration relative to sham-treated controls (54.3% missing IHCs in the scRNA group compared to 24.9% in the siHes1 groups; p < 0.001; Figure 2D). As was observed for OHC recovery, the high-frequency region in this cohort presented with greater net restoration of IHC numbers (Δ45.1% or approximately 370 IHCs/cochlea) than the low-frequency region (Δ18.5% or approximately 270 IHCs/cochlea; p < 0.001). However, the relative extent of IHC restoration (∼2-fold) between these two regions of the OC was similar, as the extent of IHC loss in the low-frequency region was approximately 50% less than that observed in the high-frequency region. As denoted in the previous section, the injurious noise exposure was centered at a frequency of 4 kHz (Figures 2A and 2B), suggesting that the excitotoxic trauma around this tonotopic position was anticipated to be the most severe.32, 33 The results from these quantitative HC evaluations support this hypothesis, as both greater HC losses and lesser therapeutic restoration were contextually observed across the 2.7–5.4 kHz tonotopic range in scRNA- and siHes1-NP-treated ears, respectively.

Correlation between ABR Thresholds and HC Loss

The correlation between ABR thresholds and HC loss was analyzed at the 2-, 4-, 8-, and 16-kHz tonotopic frequency regions. A moderate to strong correlation was observed between ABR thresholds and OHC loss, as well as between ABR thresholds and IHC loss (*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01; Table 1). In general, a stronger correlation was observed in the lower (2 and 4 kHz) frequency regions than in the higher (8 and 16 kHz) frequency regions (Table 1). These results are consistent with previous reports.34

Table 1.

Correlation between ABR Thresholds and HC Loss

| IHC | OHC | |

|---|---|---|

| 2 kHz | 0.62* | 0.60* |

| 4 kHz | 0.59* | 0.74** |

| 8 kHz | 0.53 | 0.55 |

| 16 kHz | 0.59* | 0.49 |

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

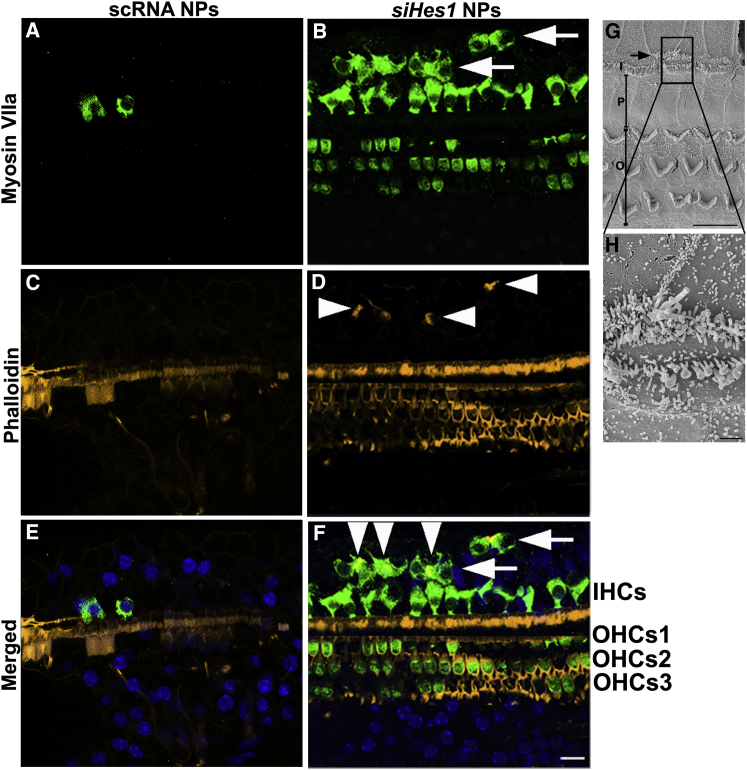

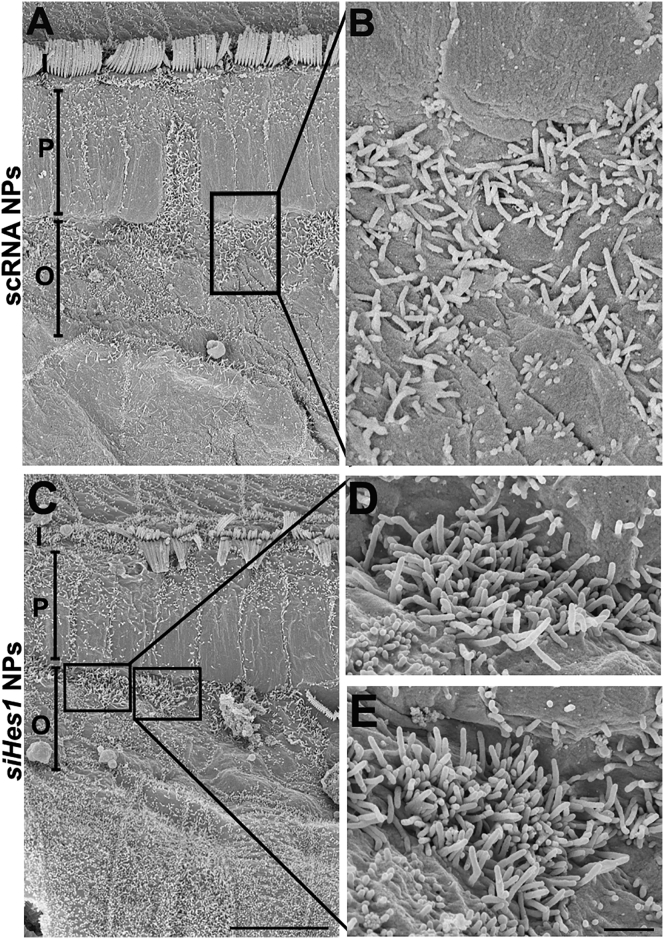

Supernumerary and Immature HCs Were Uniquely Identified in siHes1-NP-Infused Cochleae

Clusters of supernumerary IHCs were uniquely observed in 50% of the cochleae (5 out of 10) treated with siHes1 NPs at both three and nine weeks after treatment (Figure 3). Whereas many of these ectopic, myosin VIIa-positive IHCs presented with phalloidin-positive stereociliary structures (arrowheads, Figures 3D and 3F), some lacked either stereocilia or cuticular plates, indicative of a functionally immature morphology (arrows, Figures 3B and 3F). Most of these ectopic HCs were located within the basal and second turns of the OC, proximal to the therapeutic infusion site (Figure 3). No such ectopic HCs were observed in any of the noise-injured cochleae treated with scRNA NPs (0 out 8; Figures 3A, 3C, and 3E).

Figure 3.

Supernumerary IHCs Were Uniquely Observed in siHes1 NP-Treated Cochleae

(A–F) HCs were immunolabeled with anti-myosin VIIa (green in A, B, E, and F), whereas stereocilia were labeled with fluorophore-conjugated phalloidin (yellow in C–F). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue in E and F). Supernumerary IHCs (arrows in B and F) were observed only in noise-deafened OCs treated with siHes1 NPs. Some ectopic IHCs possessed phalloidin-labeled stereocilia (arrowheads in D and F), whereas some presented with no stereocilia (arrows in F). No ectopic HCs were observed in cochleae treated with scRNA NPs (A and E). (G and H) Scanning electron microscope image of an ectopic IHC in an siHes1-NP-treated OC is shown. Ectopic IHCs (arrow in G) with stereociliary structures were also observed by scanning electron microscopy in OCs at three weeks after siHes1 NP treatment (image collected from the 2nd turn of the OC). At this time point, the majority of HCs possessed stereocilia with normal morphology (G). I, P, and O in (G) indicate IHCs, pillar cells, and OHCs, respectively. The scale bars represent 50 μm in (F) for (A)–(F), 10 μm in (G), and 1 μm in (H).

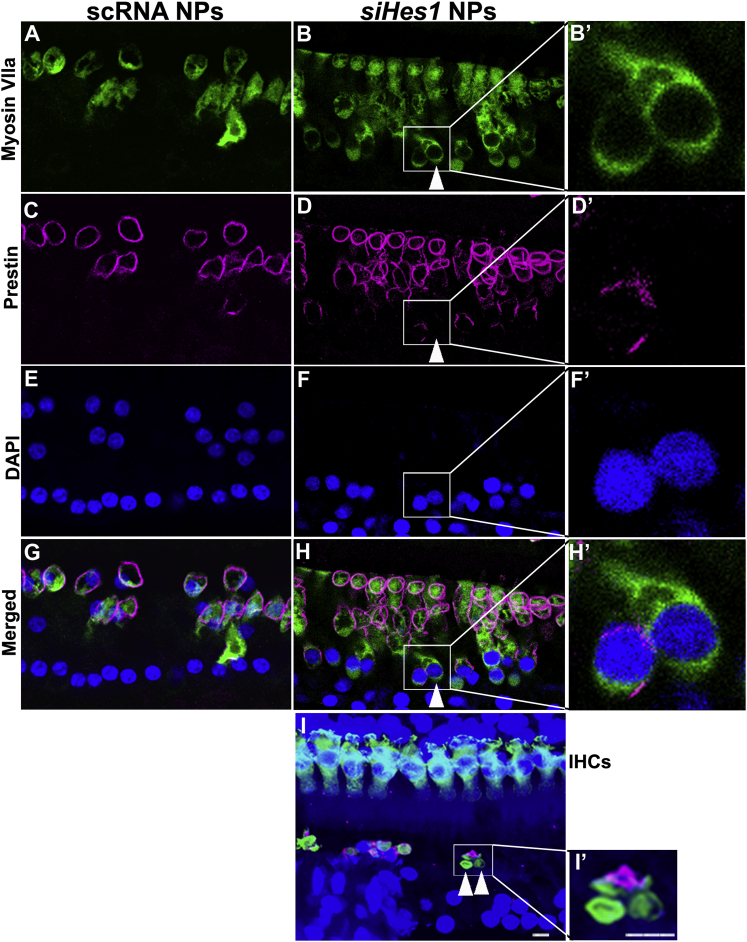

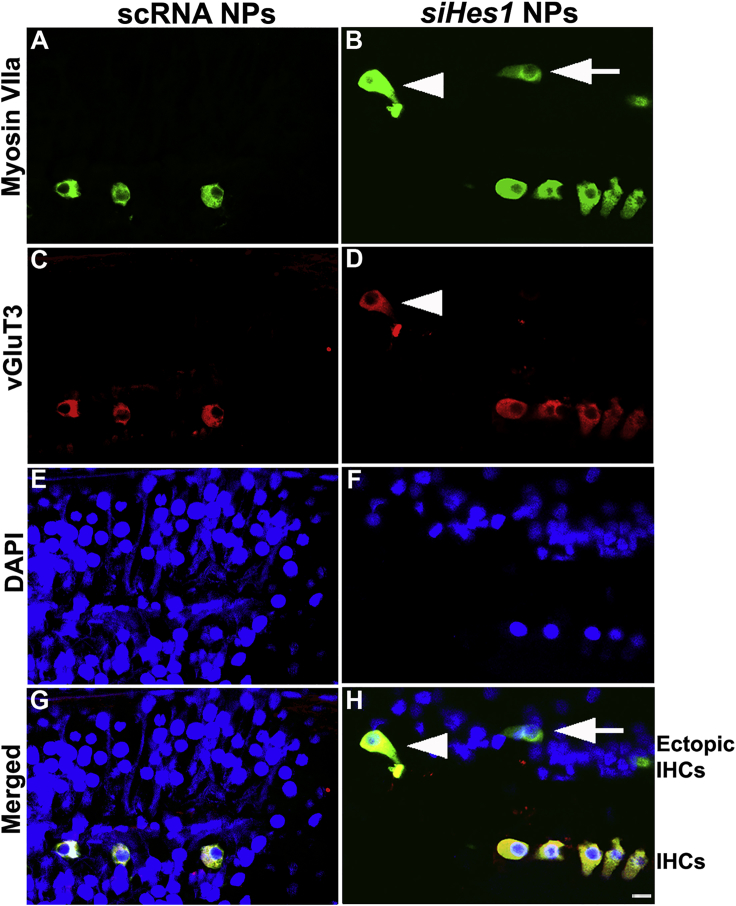

Prestin and vGluT3 are terminal differentiation markers for OHCs and IHCs, respectively, and can thus be used to distinguish mature from immature HCs in the OC.35, 36, 37 Although the vast majority of repopulated IHCs and OHCs at both intermediate and terminal evaluation intervals (i.e., three and nine weeks post-treatment) appeared phenotypically normal, immature myosin-VIIa-positive OHCs, lacking prestin expression, were also observed in OCs treated with siHes1 NPs at three weeks after treatment (Figure 4). Whereas some of these immature, prestin-negative OHCs possessed normal cellular morphology (Figure 4H’), others presented with degenerative features, such as condensed or fragmented nuclei and shrunken cell bodies (Figure 4I’).38 Immature IHCs immunopositive for myosin VIIa but lacking detectable vGluT3 expression were also uniquely observed in cochleae treated with siHes1 NPs (Figure 5). No such immature myosin-VIIa-positive/prestin-negative OHCs or myosin-VIIa-positive/vGluT3-negative IHCs were observed in OCs from cochleae treated with scRNA NPs (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4.

Immature OHCs Were Observed in OCs Treated with siHes1 NPs

Immature OHCs were observed in OCs treated with siHes1 NPs by differential prestin immunolabeling at nine (A–H’) and three (I and I’) weeks after treatment. HCs were immunolabeled by anti-myosin VIIa (green in A, B, B’, and G–I’), whereas mature OHCs were immunolabeled with anti-prestin (pink in C–D’ and G–I’). Nuclei were labeled with DAPI (blue in E–I’). Arrowheads in B, D, and H indicate a myosin-VIIa-positive/prestin-negative immature OHC in the 2nd turn of a noise-injured OC treated with siHes1 NPs at nine weeks post-treatment. This immature OHC has an apparently normal OHC morphology (H’). Arrowheads in (I) indicate two myosin-VIIa-positive/prestin-negative OHCs adjacent to a myosin-VIIa-positive/prestin-positive OHC in a noise-injured OC at three weeks post-siHes1 NP treatment. These OHCs were anucleate and small in size (I’). All OHCs in noise-deafened ears treated with scRNA NPs possessed dual labeling with myosin Vlla and prestin (G). The scale bars represent 10 μm in (I) and (I’) and apply to (A)–(I) and (B’), (D’), (F’), (H’), and (I’), respectively.

Figure 5.

Immature IHCs Were Observed in OCs Treated with siHes1 NPs

(A–F) HCs were immunolabeled with myosin VIIa antibodies (green in A, B, G, and H), whereas mature IHCs were differentially immunolabeled with vGluT3 (red in C, D, G, and H). Nuclei were labeled with DAPI (blue in E–H). Arrows in (B) and (H) indicate a myosin-VIIa-positive/vGluT3-negative ectopic immature IHC in a noise-injured OC at nine weeks post-siHes1 NP treatment. Arrowheads in (B), (D), and (H) indicate a myosin VIIa/vGluT3-positive ectopic IHC in the same siHes1-NP-treated OC. All IHCs in OCs treated with scRNA NPS were double labeled with myosin VIIa and vGluT3 (G). The scale bar represents 10 μm in (H) for (A)–(H).

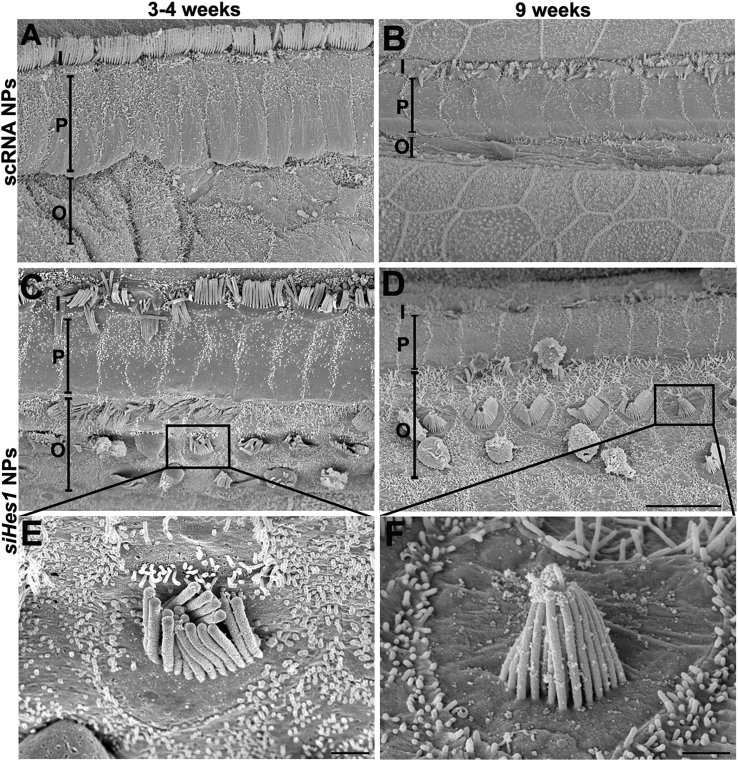

Immature HCs Identified by Scanning Electron Microscopy

At both three and nine weeks after treatment, OHCs with short kinocilia and stereocilia were observed in cochleae treated with siHes1 NPs (Figures 6C–6F). Unlike the canonical v-shaped, stair-step-like stereocilia organization of mature OHCs, the stereocilia on these HCs were short, uniform in length, and angled toward the center of the bundle. The kinocilia on these HCs were approximately 2.5 μm in length (Figures 6E and 6F), whereas kinocilia on mature HCs in undamaged cochleae are approximately 8 μm in length.39 No such scanning electron microscope evidence for immature HCs was observed in scRNA-NP-treated OCs, where the majority of OHCs were eliminated (Figures 6A and 6B).

Figure 6.

Scanning Electron Microscope Images of HCs with Morphologically Immature Stereocilia in OCs Treated with siHes1 NPs

(A and B) OHCs were efficiently ablated in the basal turns of noise-injured OCs treated with scRNA NPs at both 3 (A) and 9 (B) weeks after treatment. The original OHC region appeared narrow and progressively diminished over time (A and B). (C and D) In contrast, noise-injured ears treated with siHes1 NPs presented with a significant population of basal OHCs, the majority of which were in cytoarchitecturally correct positions within the OC and possessed morphologically mature stereociliary structures. However, HCs bearing short stereocilia, which angled toward the center of the bundle and lacked the canonical stair-step organization, were also uniquely observed in the OHC region of OCs treated with siHes1 NPs (C–F). I, P, and O in (A)–(D) indicate IHCs, pillar cells, and OHCs, respectively. The scale bars represent 10 μm in (D) for (A)–(D) and 1 μm in (E) and (F).

A distinct population of hair-cell-like cells bearing dense bundles of short, disorganized stereocilia was also observed in the basal turns of cochleae treated with siHes1 NPs (Figures 7C–7E). These stereocilia were about 1 μm in length and were markedly taller and distinguishable from the ciliary structures on adjacent SCs, instead resembling the apical surfaces of immature HCs.18, 40, 41 Again, no such structures were observed among OCs treated with scRNA NPs (Figures 7A and 7B).

Figure 7.

Clusters of Immature HCs with Short, Dense Stereocilia Bundles Were Observed by Scanning Electron Microscopy in Noise-Deafened Cochleae Treated with siHes1 NPs

(C–E) Clusters of immature HC-like cells with dense and short stereocilia were also observed in the basal turn of cochleae adjacent to the pillar cell region at nine weeks after siHes1 NP treatment. (A and B) Such cells were not observed in noise-ablated cochleae treated with scRNA NPs. I, P, and O in (A) and (C) indicate IHCs, pillar cells, and OHCs, respectively. The scale bars represent 10 μm in (C) for (A) and (C) and 1 μm in (E) for (B), (D), and (E).

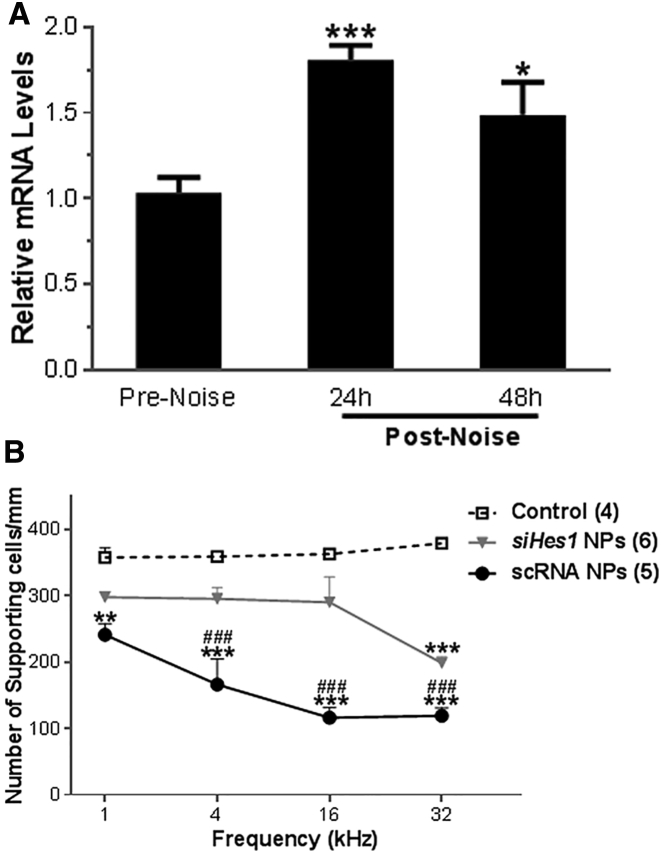

Elevated Hes1 Expression in the OC after Noise Exposure

Tissues samples for qRT-PCR were collected prior to noise exposure (pre-noise) or at 24 and 48 hr after the acoustic insult (post-noise). The noise exposure paradigm employed in this study resulted in significantly elevated cochlear Hes1 mRNA levels (∼1.8-fold at 24 hr and ∼1.5-fold at 48 hr after noise exposure; Figure 8A), similar to previously published reports of noise-induced Notch pathway activation in guinea pigs.27 The noise exposure also resulted in significantly elevated Hes5 mRNA levels in the cochlea 48 hr after noise exposure (∼1.7-fold compared to pre-noise; p < 0.01) whereas only a modest elevation was observed at 24 hr after noise exposure (∼1.3-fold compared to pre-noise; p > 0.05).

Figure 8.

Elevated Hes1 mRNA Expression and Decreased Number of SCs Were Observed in Noise-Deafened Cochleae

(A) Hes1 mRNA expression in the cochlea becomes elevated in response to acute noise injury. The acoustic trauma employed in this study (125 dB SPL centered at 4 kHz for 3 hr) resulted in elevated cochlear Hes1 mRNA levels (∼1.8-fold at 24 hr and ∼1.5-fold at 48 hr after noise exposure; *p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.001 versus pre-noise control group; n = 3 guinea pigs per group). Tissue samples for qRT-PCR were either collected prior to noise exposure (pre-noise) or at 24 and 48 hr after the noise injury (post-noise). (B) Supporting cell quantification among sham- and siHes1-NP-treated ears of noise-deafened guinea pigs is shown. SCs were counted in the OHC regions corresponding to the 1-, 4-, 16-, and 32-kHz tonotopic frequency positions from age-matched undamaged controls (dotted line) or noise-injured cochleae treated with either scRNA (sham) NPs (solid line) or siHes1 NPs (gray line) and statistically analyzed. The number of SCs in noise-injured cochleae treated with scRNA NPs was significantly decreased in all four frequency regions compared to normal controls or the siHes1 NP treatment group (p < 0.01 or 0.001). Although reduced relative to undamaged controls, SC numbers in siHes1-NP-treated ears were markedly higher than sham-treated ears across the 4- to 32-kHz regions (###, all p < 0.001). Within the scRNA group, supporting cell numbers were significantly less at 16- and 32-kHz tonotopic positions compared to the number counted at the 1-kHz position (all p < 0.01). Errors bars represent the SEM. Numbers in parentheses represent the number of ears evaluated in each group. ** and *** indicate statistically lower SC counts compared to the normal control group (p < 0.01 and 0.001, respectively); ### indicates a statistically significant difference (p < 0.001) in SC numbers compared to the siHes1 NP treatment group.

Quantitative SC Evaluations

SC counts were also performed at defined tonotopic regions within noise-injured OCs from both scRNA-NP- and siHes1-NP-treated animals and compared to SC counts performed among age-matched normal controls. In undamaged OCs, SC densities in the OHC region were relatively uniform among the tonotopic sampling regions, ranging from an average of 357.5/mm at 1 kHz to 378.75/mm at 32 kHz. Overall, SC numbers were decreased across these sampling regions in the siHes1 NP treatment group compared to normal controls. However, significant differences in total SC numbers were observed only across the 32-kHz sampling region (p < 0.001; Figure 8B). In contrast, the SC numbers were significantly reduced in the scRNA group in all three frequency regions compared to either normal controls or the siHes1 NP treatment group (p < 0.01 or 0.001; Figure 8B). In these cochleae, a pronounced basal-to-apical gradient of SC loss was measured, such that the 32-kHz frequency region possessed approximately 49.4% of the number of SCs as the 1-kHz region (p < 0.01). These results seem to indicate that, in the absence of a viable OHC population, the OC continues to degenerate, eschewing SCs as it forms flat epithelia. Taken together, these results imply that siHes1 NP treatment restores HC numbers in the OC to an extent that maintains a proper cytoarchitectural framework, thus preventing further atrophy of the sensory epithelium.

Discussion

In the present study, we found that infusion of siHes1-encapsulated PLGA NPs into the cochleae of noise-deafened adult guinea pigs resulted in specific and significant hearing improvements over a broad tonotopic frequency range compared to cochleae infused with sham (scRNA) NP controls. The marked siHes1-NP-mediated hearing improvements were accompanied by significant, treatment-specific increases in both IHC and OHC numbers in the noise-ablated OCs. Whereas the recovered populations of IHCs and OHCs were typically organized in anatomically correct positions within the OC, we also observed evidence of ectopic HCs outside of the typical cytoarchitecture of the sensory epithelium, consistent with forced induction of the HC phenotype. Moreover, morphologically immature HCs were uniquely observed in the siHes1-NP-treated ears, providing additional histologic evidence of HC regeneration in this non-transgenic animal model.18, 41, 42, 43, 44 Although, siHes1 NP treatment replenished IHC and OHC numbers throughout the noise-injured OC, the greatest extent of recovery was observed in the basal turn of the cochlea, proximal to the infusion site, in a region that is often recalcitrant to HC-regenerative strategies.19, 20

Consistent with our findings, pharmacologic manipulation of the Notch pathway has previously been shown to restore cochlear HC numbers and a degree of hearing recovery in adult animals after a deafening acoustic trauma,20, 37 despite the fact that previous studies had suggested that the capacity for cochlear HC regeneration through attenuation of Notch signaling declines considerably during developmental maturation of the OC.35, 45 However, the magnitude and tonotopic breadth of functional restoration reported herein for targeted silencing of a single Notch effector gene was seemingly more robust than that anticipated from previous studies, with more than 10 dB of ABR threshold recovery measured at test frequencies of 4, 8, and 16 kHz in siHes1-NP-treated ears and greater than 10 dB improvement in all four test frequencies, including 2 kHz, in comparison to scRNA-NP-treated controls. In a series of published studies on speech intelligibility in humans, it has been consistently determined that the just-noticeable-difference (JND) in discriminating a difference in sound intensity lies between 2 and 3 dB.46, 47, 48 Therefore, a 3-dB improvement in hearing threshold would be clinically relevant, whereas a 6-dB improvement would represent a doubling of the JND. The measured threshold improvements of 10 dB or more reported herein at multiple test frequencies represent more than a 3× JND improvement and a greater than two-fold increase in perceived loudness, which would be predicted to correspond to clinically detectable differences in speech threshold in humans.48 Moreover, a 10-dB improvement in hearing function at one or more frequencies has been used as a primary endpoint criterion for assessing clinically meaningful hearing improvement in human clinical studies.49, 50, 51, 52

In addition to being robust, the treatment-specific functional recovery elicited by cochlear siHes1 NP infusion was also enduring. Several HC regenerative studies have documented treatment-specific restoration of transient populations of HC-like cells in the OC that remain morphologically and functionally immature and are subsequently lost.37, 53 Our results demonstrate the restoration of sustainable IHC and OHC populations throughout the OC and an accompanying functional recovery that persisted from the initial ABR recording interval at three weeks post-treatment and extended out to the terminal nine-week interval. However, we identified subpopulations of immature, myosin-VIIa-positive OHC-like cells and IHC-like cells that were either prestin- or vGluT3-negative, respectively, or possessed rudimentary stereocilia bundles, indicating that some new HCs failed to achieve functional maturity over the time course of this study. Additionally, anucleate, degenerating myosin-VIIa-positive/prestin-negative OHCs were also observed at three weeks post-treatment, consistent with a degree of deterioration among a subpopulation of the newly repopulated HCs (arrowheads in Figures 4I and 4I’). These observations may indicate that additional developmental factors or cellular constituents may be contextually required for optimal realization of the mature phenotype.53, 54, 55 Nonetheless, a significant proportion of the repopulated IHCs and OHCs that were observed in the siHes1-NP-treatment group presented with biomarkers and stereociliary structures that reflected functional maturation.

Although we are unable to formally rule out the possibility that siHes1 NP treatment may confer a degree of protection against the loss of pre-existing HCs in noise-injured ears in this non-transgenic animal model, several lines of evidence suggest otherwise. For instance, previous studies have demonstrated that HC loss in mammals occurs rapidly (within the first 12 hr post-injury) following a prolonged high-energy noise exposure.32, 56 In related studies, approximately 65% of HCs were ablated in guinea pig cochleae within the first 48 hr after a 130-dB SPL noise exposure for 15 min, and the percentage reached 85% at 5 days after noise exposure.57 We exposed the animals to 125 dB SPL noise for 3 hr, the sound energy of which is 3.79 times of a 130-dB SPL noise exposure for 15 min (http://www.eurovent-certification.com/fic_bdd/pdf_fr_fichier/1137149375_Review_67-Bill_Cory.pdf), suggesting a far greater damaging effect on primary HC loss. Using a transgenic mouse model to lineage trace the origins of new HCs, Mizutari and colleagues demonstrated that regenerative intervention at 24 hr post-injury using a gamma-secretase inhibitor (GSI) for pan Notch inhibition did not result in significant preservation of pre-existing HCs, indicating that an even more acute inhibition of Notch and Hes1 signaling was not protective against HC loss.20 Moreover, other effective intervention strategies, such as antioxidant intervention with N-acetylcysteine, that are designed to mitigate the progressive pathophysiological responses induced by an acute acoustic trauma (AAT) have been shown to be ineffective when administered more than one hour post-injury.58 Therefore, in light of the fact that we delayed intervention for 72 hr post-trauma, the most plausible explanation for the degree and tonotopic breadth of HC restoration that we observed in siHes1-NP-treated ears is that of bona fide regeneration.

Generation of new HCs from direct transdifferentiation of SCs is predicted to occur at the expense of the SC population, thus reducing their prevalence in OCs.20, 23 Consistent with this rationale, we observed a decline in the number of DAPI-stained nuclei in the SC layer (relative to undamaged control ears) in siHes1-NP-treated ears across the 1-, 4-, 16-, and 32-kHz tonotopic frequency regions sampled in our analyses (297.5, 295, 290, and 198.33 SCs/mm for 1, 4, 16, and 32 kHz, respectively; Figure 8B). However, these apparent SC deficits were only sufficient to account for the extent of repopulated HCs in the 32-kHz tonotopic region among siHes1-NP-treated ears. Interpretation of these results is complicated by the fact that markedly greater SC loss was observed in scRNA-NP-treated ears, in which widespread HC restoration was not observed.

Several explanations can be proffered to account for these apparent discrepancies. For instance, a similar finding was previously documented by Izumikawa and colleagues following adenoviral-mediated SC transdifferentiation through forced Atoh1 expression in noise-deafened guinea pigs.18 In these animals, the active therapeutic paradoxically increased the number of SCs in the OCs after treatment relative to the widespread losses documented in untreated ears.18 The authors postulated that non-sensory cells may have been recruited to surround new HCs to structurally, if not functionally, replace transdifferentiated SCs through migratory and/or proliferative processes.59, 60, 61 Although forced transdifferentiation through inhibition of Notch signaling has previously been thought to represent a non-mitotic process in mammalian cochleae, recent work by Li and colleagues has challenged that paradigm by demonstrating that contextual in vivo deletion of Notch1 in post-natal OCs was capable of inducing a significant SC proliferative response.62 Thus, it is possible that reversible silencing of the Notch pathway effector, Hes1, may elicit a similar response in vivo, thereby promoting a degree of in situ SC replacement in a manner analogous to that which occurs in avian cochleae.63 In scRNA-NP-treated cochleae, the marked SC loss that we observed at nine weeks post-injury is most likely attributable to progressive degeneration of the OC following excitotoxic loss of HCs, particularly in the basal turn. Indeed, in this region of the OC, flat epithelium was evident by light microscopy and scanning electron microscopy in scRNA-NP-treated ears. A similar profile of delayed, yet pervasive, SC loss in response to a high-energy acoustic trauma that resulted in the widespread “wipe out” of HCs was recently documented in chinchillas, coinciding with the formation of flat epithelium.32 Thus, our observations on the effects of trauma and treatment on SC populations within the OC indicate that, in the absence of HC restoration and the appropriate cellular microenvironment, the residual SC population experienced widespread apoptosis and conversion to an expanded squamous epithelium.

We used PLGA NPs as carriers to deliver siRNA into the cellular constituents of the cochlea. The technological advantages of using NPs as drug carriers are myriad, including enhanced stability, high carrier capacity, sustained release, and biocompatibility with sensitive epithelia.23, 64, 65, 66 PLGA encapsulation is also advantageous over naked RNA, as it allows for tailored optimization and strategic evolution of the therapeutic formulation, such that siRNA release rates and particle degradation characteristics can be fine-tuned by modifying the properties of the matrix constituents, and therapeutic payloads can be strategically targeted to desired cellular or tissue components by introducing homing factors (e.g., ligands or antibodies) to the NP surface.67, 68, 69 Our lab and others have shown that PLGA-based NPs efficiently cross cell boundaries and are efficiently endocytosed by a variety of cells within the cochleae, including SCs.23, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74 Once internalized, the intrinsic capacity of the PLGA NP surface to become reversibly cationized in the low pH environment of endo-lysomal vesicles allows for the rapid (<10 min) release of these delivery agents into the cytoplasm, preventing the hydrolytic degradation of the unmodified siRNA payloads within this intracellular compartment. Upon cytoplasmic release, progressive erosion of the PLGA matrix promotes sustained silencing of target genes through continuous release of the siRNA payload, as has been previously demonstrated in cochlear tissues for siHes1.23, 75 These inherent attributes provide a compelling foundation for further refinement of this therapeutic approach that leaves the established efficacy of the therapeutic payload unchanged while potentially enhancing the efficiency and specificity of drug delivery.

In the present study, a significant and clinically relevant degree of functional improvement was observed over a broad tonotopic range using specific pharmacological inhibition of a single Notch pathway effector protein. Efficacy was achieved by employing a single, one-day infusion of siHes1 NPs directly into the cochlea. However, it is possible that greater in vivo efficacy may be achievable through multiple dosing or prolonged infusion. In pilot experiments, we have observed that a seven-day infusion of a single bolus of siHes1 NPs yielded a similar degree of total functional recovery to that documented herein for the one-day infusion, although the therapeutic effects were more gradual, showing progressive functional gains at successive test intervals (data not shown). In both instances, siHes1 NPs were delivered into the cochlea through cochleostomy, which can cause 5–10 dB hearing loss.76 As such, a non-traumatic therapeutic approach for drug delivery to the cochlea, e.g., middle ear delivery across the round window membrane, may promote greater net gains in both HC restoration and functional recovery. This alternative, clinically relevant delivery route has already been shown to be amenable to the passage and subsequent inner ear uptake of PLGA NPs, making it an attractive option for future studies.71, 77, 78

Materials and Methods

Animals

Young female pigmented guinea pigs (Cavia porcellus) with body weight 200–250 g were purchased from Elm Hill Labs (Chelmsford, MA). Animals were housed in the animal facility at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation (OMRF). The animals were kept on a normal day/night cycle with free access to food and water. All procedures regarding the use and handling of animals were reviewed and approved by the OMRF Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Noise Exposure

Guinea pigs were anesthetized with ketamine (60 mg/kg) and xylazine (4 mg/kg) and exposed to a 125-dB SPL octave-band noise centered at 4 kHz for three hours on a non-sound-reflective platform positioned in an open sound field. This noise exposure paradigm was designed and tailored to consistently induce permanent threshold shifts in ABR and cochlear HC loss in the basal and second turns of the guinea pig cochlea.79

The noise exposure, with a 12-dB per octave roll-off, was digitally generated by a RP2.1 enhanced real-time processor (Tucker-Davis Technologies, USA) in conjunction with RPvdsEx software 5.4 (Tucker-Davis Technologies, USA), amplified by a PLX-3402 power amplifier (QSC, USA), and delivered by a JBL-2446H driver through a JBL-2380a horn (JBL Professional, USA). Noise levels were measured and continuously monitored at the level of the exposed ears, using a B&K type 4189 1/2-inch microphone connected to a B&K type 2671 preamplifier in synchrony with a B&K PULSE sound measurement software (Bruel & Kjaer, Denmark).

qRT-PCR Analyses

To prepare cochlear RNA from noise-exposed guinea pigs, 6 guinea pigs were exposed to 125 dB noise for 3 hr. Twenty-four (3 guinea pigs) or forty-eight hours (3 guinea pigs) after noise exposure, temporal bones were dissected in sterile, nuclease-free PBS (Ambion) using a dissecting microscope. Cochleae from 3 guinea pigs without noise exposure were used as normal controls. The bony shell of the cochleae was removed, and cochlear soft tissue (the OC on the basal membrane and the stria vascularis) were collected in a sterile, nuclease-free centrifuge tube and immediately frozen on dry ice prior to storage at −80°C until the time of RNA extraction. Cochlear soft tissues were submerged and dissolved in TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and subsequently extracted according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNase treatments of the resultant RNA pools were performed using the Ambion Turbo DNA free kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). cDNA pools were then generated from each sample by reverse transcription using 100 ng of total RNA and the qScript cDNA Supermix kit (Quantabio, Beverly, MA), according to the manufacturer’s suggested guidelines. The resultant products were subjected to qRT-PCR analyses on an ABI Prism 7000 PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with SYBRGreen Gene Expression Assays (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), using primers specific to guinea pigs transcripts encoding Hes1 (forward, 5′-CAGCCAGCTGAAAACACTGA-3′; reverse, 5′- GTCACCTCGTTCATGCACTC-3′), Hes5 (forward, 5′-AGCCTGTGGTGGAGAAGATG-3′; reverse, 5′-TAGTCTCGGTGCAGGCTCTT-3′), and the housekeeping gene GAPDH (forward, 5′-GTCGGTTGTGGATCTGACCT-3′; reverse, 5′-TGCTGTAGCCGAACTCATTG-3′) as an internal control for normalization. For each gene, triplicate qRT-PCR reactions were assayed. Relative expression levels were determined by the 2-ΔΔCT method.80

ABR Measurements

ABR testing was performed in a sound-attenuated and electrically shielded booth prior to the noise exposure injury (baseline), 24 hr after noise injury, and then repeated at three, six, and nine weeks after siHes1 or scRNA NP treatment. Animals were anesthetized with ketamine (60 mg/kg) and xylazine (4 mg/kg) during testing. Body temperatures were maintained at 37°C with a FHC temperature controller (FHC-40908D; FHC, Bowdoin, ME).

For ABR recording, an inverting input and a ground needle electrode were subcutaneously placed posterior to the stimulated (ipsilateral) and non-stimulated (contralateral) ears, respectively, while a non-inverting input was placed at the vertex of the animal. Acoustic stimuli consisting of tone bursts at frequencies of 2, 4, 8, and 16 kHz (0.5 ms rise/fall; 5 ms duration) at the rate of 19.7/s were generated digitally (SigGen; TDT, Alachua, FL) by a D/A converter (RX6; TDT), fed to a free-field magnetic speaker (MF1; TDT) through a programmable attenuator (PA5; TDT) and amplifier (SA1; TDT), and delivered by a speaker, with the contralateral ear canal sealed. The electrode outputs were delivered to a preamplifier/base station (RA4LI and RA4PA; TDT) and then filtered (300–3,000 Hz), amplified (20×), and averaged by the TDT system. ABR threshold, tested separately for each ear, was defined as the lowest dB level of stimulation, at which peak 2 of the ABR waveform could be positively recognized from two consecutive ABR trials. A maximum intensity of 80 dB SPL was employed and decreased in 5-dB steps to determine the threshold. Ears that were unresponsive at 80 dB SPL were assigned a threshold of 90 dB SPL.

Permanent ABR threshold shifts were measured as the difference between the pre-injury baseline thresholds and the ABR thresholds measured at 3, 6, and 9 weeks after treatment with either sham (scRNA) NPs or therapeutic siHes1 NPs. ABR measurements were conducted by an electrophysiologist whom was blinded to the treatment group of each animal.

siRNA Nanoparticle Delivery into the Cochleae of Guinea Pigs

The noise-exposed animals were randomly assigned into two groups, siHes1 NP group (siHes1 group; n = 11) and scRNA NP group (scRNA group; n = 9), which received either siHes1 NPs or scRNA NPs, respectively. siHes1 or scRNA NPs were delivered into the cochleae by an alzet mini-Osmotic pump (1.0 μL per hour; model 2001; Durect, Cupertino, CA) three days after noise exposure. Pumps were loaded with siHes1 NPs at a concentration of 800 μg/mL in artificial perilymph solution.81 This concentration was selected due to its optimal efficacy for HC regeneration in our previous in vitro study.23 Sham (scRNA) NPs were delivered at the same concentration.

Pump implantation was conducted according to a previously published procedure.76 Briefly, guinea pigs were anesthetized with 2%–4% isoflurane, and a retroauricular surgical approach was used to expose the bulla. The bulla opening was then drilled with a diamond burr to expose the round window and the basal turn of the cochlea with a surgical microscope. A small hole was made in the bony wall of the basal turn slightly lateral to the round window. The tip of the pre-loaded (sham or siHes1 NPs) cannula was then inserted into the hole until the silicone drop was seated against the otic capsule. The cannula was then secured in place bulla with dental acrylic and looped around a small stainless steel screw self-tapped into a hole drilled in the skull. A subcutaneous pocket was then surgically formed between the scapulae to accommodate the pump. The pumps were removed 24 hr after implantation. Ciprofloxacin and Buprenex were administered for infection prevention and pain relief after surgery.

Immunohistology and HC Quantification

Guinea pigs were euthanized at 3 or 4 weeks (for myosin VIIa, prestin, and vGluT3 labeling) or 9 weeks (for myosin VIIa and phalloidin staining or myosin VIIa, vGluT3, and prestin staining) after siRNA NP application. Animals were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine and intracardially perfused with saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.2). Cochleae were removed and post-fixed in the same fixative overnight. The fixed tissues were then washed in PBS and stored in PBS at 4°C until dissection. Basilar membranes with organs of Corti were dissected out and immunolabeled for prestin, vGlut3, and myosin VIIa for identifying immature HCs or myosin VIIa and phalloidin for HC counting.

For HC marker immunolabeling, intact basilar membranes with organs of Corti were blocked in 1% BSA and normal donkey serum in PBS containing 0.2% Triton x-100 (PBS/T) for 1 hr at room temperature and then incubated with rabbit anti-myosin VIIa (1:1,000; cat no.: 25-6790; Proteus Biosciences, Ramona, CA) in a refrigerator overnight. After washing with PBS, the tissues were incubated with Alexa 488 donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (1:1,000; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 4°C overnight. After washing with PBS, DAPI (1:500) and 0.01% TRITC-phalloidin were used to label the nuclei and HC stereocilia, respectively. The tissues were flat mounted in anti-fade medium on glass slides. OCs were examined under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX51, Melville, NY) with 40× magnification. The number of HCs was estimated in 6 cochleae in the scRNA group and 7 in the siHes1 group at nine weeks after treatment. The IHCs and OHCs were counted from the apex to the base in 200-μm segments, and the percentage of missing HCs was plotted as cytocochleograms. HC counting was blindly conducted by a technician who was unaware of the identities of the samples on each slide.

For immature OHC and IHC marker immunolabeling, cochleae from each treatment group (scRNA NP or siHes1 NP) were harvested at either three weeks (two from siHes1 NP cohort and one from scRNA NP cohort) or nine weeks (two from each group) for histological evaluation. Basilar membranes with organs of Corti were incubated with 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (without Tween 20 [pH 6.0]) overnight at 58°C and then blocked in 1% BSA and normal donkey serum in PBS for one hour at room temperature. After blocking, the tissues were incubated with rabbit anti-myosin VIIa, goat anti-prestin (1:20; cat no.: OAEB00391; Aviva Systems Biology, San Diego, CA), and mouse anti-vGlut3 (1:25; cat no.: 135211; Synaptic Systems, Goettingen, Germany) at 4°C overnight. After washing with PBS, the tissues were incubated with Alexa 488 donkey anti-rabbit IgG, Alexa Fluor 568 donkey anti-mouse IgG, and Alexa Fluor 647 donkey anti-goat IgG (all at 1:1,000; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 4°C overnight. DAPI (1:500) was used to stain nuclei. Immature HCs were examined with a Zeiss LSM-710 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, NY). These cochleae were also evaluated for HC and SC counting.

To estimate the number of SCs in the guinea pig cochlea, the whole cochlea was photographed with an epifluorescence microscope. The cochlear length was measured, whereas the frequency was computed using a custom plug-in ImageJ software (https://www.masseyeandear.org/research/ent/eaton-peabody/epl-histologyresources/). Images were collected with a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM-710). Three tonotopic frequency positions (1, 4, and 16 kHz) from cochlea were selected for image collection. SC nuclei were quantified at each position and distinguished from myosin-VIIa-positive OHCs based on their distinct focal planes. Nuclei from myosin-VIIa-positive cells were excluded from this quantitative analysis. Four cochleae from normal control animals without noise exposure were used as reference standards in HC and SC quantitative evaluations.

Scanning Electron Microscopy

For the scanning electron microscope study, guinea pigs were euthanized at either 3 or 9 weeks after surgery. Two guinea pigs from the siHes1 NP treatment group and one guinea pig from the scRNA NP treatment group were euthanized at each evaluation interval. The cochleae were perfused with PBS and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.2 M sodium cacodylate buffer (Electron Microscopy Science, Hatfield, PA) and then postfixed in the same fixative overnight. After washing three times with the sodium cacodylate buffer, the bony capsule, the spiral ligament and stria vascularis, Reissner’s membrane, and the tectorial membrane were removed. After the dissection, cochleae were post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide (OsO4; Electron Microscopy Science, Hatfield, PA) in the sodium cacodylate buffer at 4°C for two hours. The specimens were then washed three times with de-ionized water and dehydrated with serial graded concentrations of ethanol (25%–100%) and critical point dried. The specimens were then mounted onto scanning electron microscope stubs and coated with a thin layer of AuPd and photographed on a Zeiss, NeoN 40 EsB field emission dual-beam scanning electron microscope (Zeiss, Billerica, MA). Short bundles (<6 μm) of HCs were identified as documented in previous reports.42, 43, 82 HCs with short and thin kinocilia and stereocilia angled toward the center of the bundle without stair stepping were considered as newly regenerated or morphologically immature HCs.42, 43, 44

siRNA-Loaded Nanoparticle Formulation and Characterization

Unmodified Hes1 siRNA and non-targeting scRNA biomolecules were custom-synthesized by GE Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO). siHes1 contained the following nucleotide sequences: 5′-CAGCUGAUAUAAUGGAGAAtt−3′ (passenger strand) and 5′-UUCUCCAUUAUAUCAGCUGtt-3′ (guide strand). The sequences for the double-stranded scRNA were as follows: 5′-AGUACUGCUUACGAUACGGtt-3′ and 5′-CCGUAUCGUAAGCAGUACUtt-3′.

The siHes1 or scRNA-loaded PLGA NPs were prepared by the water-in-oil-in-water (w1/o/w2) double-emulsion solvent evaporation method as previously reported.83 Briefly, 15 nmol of siHes1 was added to 1,000 μL of dichloromethane (DCM) containing 100 mg of PLGA and sonicated (Microson ultrasonic cell disruptor XL; Misonix, Farmingdale, NY). The resulting emulsion was magnetically stirred (RO 10; IKA-Werke, Staufen, Germany) for two hours at room temperature to evaporate the DCM. The PLGA NPs were purified by ultracentrifugation at 13,000 g for 20 min at 4°C (TOMY MX-201 High Speed Refrigerated Microcentrifuge) and freeze dried at −100°C under 40 mTorr (Virtis Benchtop freeze-dryer, Gardiner, NY). The particle mean diameter and polydispersity index of siHes or scRNA-loaded NPs was measured by phase analysis light scattering (PALS) (Zetasizer Nano ZS series from Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, UK). The morphological characteristics were determined by scanning electron microscopy (Zeiss NEON 40 EsB field emission dual beam scanning electron microscope). The particle mean diameter was 285 ± 7.3 nm, the polydispersity index was 0.081 ± 0.002, and the zeta potential was −22 ± 6.8 mV. The amount of siRNA loaded into the PLGA NPs was 150.2 ± 5.1 pmol of siHes1/mg of NPs. Powdered NPs were stored at −80°C prior to use.

Statistical Analyses

One-way ANOVA (SPSS 14.0 for windows) and a post hoc test (Tukey-Kramer) were used to determine whether there were statistically significant differences among groups and between each of two groups in the HC and SC quantitative analyses. Mann-Whitney U test was used to analyze the hearing improvement measured by ABR after noise exposure. Pearson correlation coefficient was used in correlation analyses. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Author Contributions

X.D., Q.C., M.B.W., I.Y., X.H., W.L., W.C., D.N., and D.L.E. conducted the experiments. X.D., M.B.W., and R.D.K. designed the experiments and wrote the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Kopke is a founder and officer of Otologic Pharmaceutics Inc.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by The Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science and Technology (OCAST) grant AR15-005. The authors would like to thank Dr. Preston Larson at the University of Oklahoma Samuel Roberts Noble Electron Microscopy Laboratory for assisting with the scanning electron microscope analyses.

References

- 1.Brigande J.V., Heller S. Quo vadis, hair cell regeneration? Nat. Neurosci. 2009;12:679–685. doi: 10.1038/nn.2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cotanche D.A. Genetic and pharmacological intervention for treatment/prevention of hearing loss. J. Commun. Disord. 2008;41:421–443. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bermingham-McDonogh O., Rubel E.W. Hair cell regeneration: winging our way towards a sound future. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2003;13:119–126. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnsson L.G., Hawkins J.E., Jr. Degeneration patterns in human ears exposed to noise. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1976;85:725–739. doi: 10.1177/000348947608500603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rauch S.D., Velazquez-Villaseñor L., Dimitri P.S., Merchant S.N. Decreasing hair cell counts in aging humans. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 2001;942:220–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lanford P.J., Lan Y., Jiang R., Lindsell C., Weinmaster G., Gridley T., Kelley M.W. Notch signalling pathway mediates hair cell development in mammalian cochlea. Nat. Genet. 1999;21:289–292. doi: 10.1038/6804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zine A., Van De Water T.R., de Ribaupierre F. Notch signaling regulates the pattern of auditory hair cell differentiation in mammals. Development. 2000;127:3373–3383. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.15.3373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fekete D.M., Muthukumar S., Karagogeos D. Hair cells and supporting cells share a common progenitor in the avian inner ear. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:7811–7821. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-19-07811.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bermingham N.A., Hassan B.A., Price S.D., Vollrath M.A., Ben-Arie N., Eatock R.A., Bellen H.J., Lysakowski A., Zoghbi H.Y. Math1: an essential gene for the generation of inner ear hair cells. Science. 1999;284:1837–1841. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5421.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng J.L., Gao W.Q. Overexpression of Math1 induces robust production of extra hair cells in postnatal rat inner ears. Nat. Neurosci. 2000;3:580–586. doi: 10.1038/75753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balak K.J., Corwin J.T., Jones J.E. Regenerated hair cells can originate from supporting cell progeny: evidence from phototoxicity and laser ablation experiments in the lateral line system. J. Neurosci. 1990;10:2502–2512. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-08-02502.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brignull H.R., Raible D.W., Stone J.S. Feathers and fins: non-mammalian models for hair cell regeneration. Brain Res. 2009;1277:12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corwin J.T., Cotanche D.A. Regeneration of sensory hair cells after acoustic trauma. Science. 1988;240:1772–1774. doi: 10.1126/science.3381100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryals B.M., Rubel E.W. Hair cell regeneration after acoustic trauma in adult Coturnix quail. Science. 1988;240:1774–1776. doi: 10.1126/science.3381101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daudet N., Gibson R., Shang J., Bernard A., Lewis J., Stone J. Notch regulation of progenitor cell behavior in quiescent and regenerating auditory epithelium of mature birds. Dev. Biol. 2009;326:86–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma E.Y., Rubel E.W., Raible D.W. Notch signaling regulates the extent of hair cell regeneration in the zebrafish lateral line. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:2261–2273. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4372-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hori R., Nakagawa T., Sakamoto T., Matsuoka Y., Takebayashi S., Ito J. Pharmacological inhibition of Notch signaling in the mature guinea pig cochlea. Neuroreport. 2007;18:1911–1914. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3282f213e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Izumikawa M., Minoda R., Kawamoto K., Abrashkin K.A., Swiderski D.L., Dolan D.F., Brough D.E., Raphael Y. Auditory hair cell replacement and hearing improvement by Atoh1 gene therapy in deaf mammals. Nat. Med. 2005;11:271–276. doi: 10.1038/nm1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kraft S., Hsu C., Brough D.E., Staecker H. Atoh1 induces auditory hair cell recovery in mice after ototoxic injury. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:992–999. doi: 10.1002/lary.22171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mizutari K., Fujioka M., Hosoya M., Bramhall N., Okano H.J., Okano H., Edge A.S. Notch inhibition induces cochlear hair cell regeneration and recovery of hearing after acoustic trauma. Neuron. 2013;77:58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tona Y., Hamaguchi K., Ishikawa M., Miyoshi T., Yamamoto N., Yamahara K., Ito J., Nakagawa T. Therapeutic potential of a gamma-secretase inhibitor for hearing restoration in a guinea pig model with noise-induced hearing loss. BMC Neurosci. 2014;15:66. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-15-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Batts S.A., Shoemaker C.R., Raphael Y. Notch signaling and Hes labeling in the normal and drug-damaged organ of Corti. Hear. Res. 2009;249:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du X., Li W., Gao X., West M.B., Saltzman W.M., Cheng C.J., Stewart C., Zheng J., Cheng W., Kopke R.D. Regeneration of mammalian cochlear and vestibular hair cells through Hes1/Hes5 modulation with siRNA. Hear. Res. 2013;304:91–110. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2013.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korrapati S., Roux I., Glowatzki E., Doetzlhofer A. Notch signaling limits supporting cell plasticity in the hair cell-damaged early postnatal murine cochlea. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e73276. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin V., Golub J.S., Nguyen T.B., Hume C.R., Oesterle E.C., Stone J.S. Inhibition of Notch activity promotes nonmitotic regeneration of hair cells in the adult mouse utricles. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:15329–15339. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2057-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang G.P., Chatterjee I., Batts S.A., Wong H.T., Gong T.W., Gong S.S., Raphael Y. Notch signaling and Atoh1 expression during hair cell regeneration in the mouse utricle. Hear. Res. 2010;267:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2010.03.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang B., Liu Y., Zhu X., Chi F., Zhang Y., Yang M. Up-regulation of cochlear Hes1 expression in response to noise exposure. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. (Warsz.) 2011;71:256–262. doi: 10.55782/ane-2011-1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murata J., Ohtsuka T., Tokunaga A., Nishiike S., Inohara H., Okano H., Kageyama R. Notch-Hes1 pathway contributes to the cochlear prosensory formation potentially through the transcriptional down-regulation of p27Kip1. J. Neurosci. Res. 2009;87:3521–3534. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Su Y.X., Hou C.C., Yang W.X. Control of hair cell development by molecular pathways involving Atoh1, Hes1 and Hes5. Gene. 2015;558:6–24. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slowik A.D., Bermingham-McDonogh O. Hair cell generation by notch inhibition in the adult mammalian cristae. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2013;14:813–828. doi: 10.1007/s10162-013-0414-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cody A.R., Robertson D. Variability of noise-induced damage in the guinea pig cochlea: electrophysiological and morphological correlates after strictly controlled exposures. Hear. Res. 1983;9:55–70. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(83)90134-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bohne B.A., Kimlinger M., Harding G.W. Time course of organ of Corti degeneration after noise exposure. Hear. Res. 2017;344:158–169. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thorne P.R., Gavin J.B. Changing relationships between structure and function in the cochlea during recovery from intense sound exposure. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1985;94:81–86. doi: 10.1177/000348948509400117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Engle J.R., Tinling S., Recanzone G.H. Age-related hearing loss in rhesus monkeys is correlated with cochlear histopathologies. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e55092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu Z., Owen T., Fang J., Zuo J. Overactivation of Notch1 signaling induces ectopic hair cells in the mouse inner ear in an age-dependent manner. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e34123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Z., Fang J., Dearman J., Zhang L., Zuo J. In vivo generation of immature inner hair cells in neonatal mouse cochleae by ectopic Atoh1 expression. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e89377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Atkinson P.J., Wise A.K., Flynn B.O., Nayagam B.A., Richardson R.T. Hair cell regeneration after ATOH1 gene therapy in the cochlea of profoundly deaf adult guinea pigs. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e102077. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bohne B.A., Harding G.W., Lee S.C. Death pathways in noise-damaged outer hair cells. Hear. Res. 2007;223:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hudspeth A.J. Integrating the active process of hair cells with cochlear function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2014;15:600–614. doi: 10.1038/nrn3786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kawamoto K., Ishimoto S., Minoda R., Brough D.E., Raphael Y. Math1 gene transfer generates new cochlear hair cells in mature guinea pigs in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:4395–4400. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-11-04395.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walters B.J., Coak E., Dearman J., Bailey G., Yamashita T., Kuo B., Zuo J. In vivo interplay between p27Kip1, GATA3, ATOH1, and POU4F3 converts non-sensory cells to hair cells in adult mice. Cell Rep. 2017;19:307–320. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Forge A., Li L., Corwin J.T., Nevill G. Ultrastructural evidence for hair cell regeneration in the mammalian inner ear. Science. 1993;259:1616–1619. doi: 10.1126/science.8456284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Forge A., Li L., Nevill G. Hair cell recovery in the vestibular sensory epithelia of mature guinea pigs. J. Comp. Neurol. 1998;397:69–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walsh R.M., Hackney C.M., Furness D.N. Regeneration of the mammalian vestibular sensory epithelium following gentamicin-induced damage. J. Otolaryngol. 2000;29:351–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maass J.C., Gu R., Basch M.L., Waldhaus J., Lopez E.M., Xia A., Oghalai J.S., Heller S., Groves A.K. Changes in the regulation of the Notch signaling pathway are temporally correlated with regenerative failure in the mouse cochlea. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015;9:110. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Killion M.C., Niquette P.A., Gudmundsen G.I., Revit L.J., Banerjee S. Development of a quick speech-in-noise test for measuring signal-to-noise ratio loss in normal-hearing and hearing-impaired listeners. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2004;116:2395–2405. doi: 10.1121/1.1784440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McShefferty D., Whitmer W.M., Akeroyd M.A. The just-meaningful difference in speech-to-noise ratio. Trends Hear. 2016;20 doi: 10.1177/2331216515626570. 2331216515626570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Whitmer W.M., McShefferty D., Akeroyd M.A. On detectable and meaningful speech-intelligibility benefits. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016;894:447–455. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-25474-6_47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harris J.P., Weisman M.H., Derebery J.M., Espeland M.A., Gantz B.J., Gulya A.J., Hammerschlag P.E., Hannley M., Hughes G.B., Moscicki R. Treatment of corticosteroid-responsive autoimmune inner ear disease with methotrexate: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:1875–1883. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.14.1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nakagawa T., Kumakawa K., Usami S., Hato N., Tabuchi K., Takahashi M., Fujiwara K., Sasaki A., Komune S., Sakamoto T. A randomized controlled clinical trial of topical insulin-like growth factor-1 therapy for sudden deafness refractory to systemic corticosteroid treatment. BMC Med. 2014;12:219. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0219-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stokroos R.J., Albers F.W., Tenvergert E.M. Antiviral treatment of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss: a prospective, randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Acta Otolaryngol. 1998;118:488–495. doi: 10.1080/00016489850154603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xenellis J., Papadimitriou N., Nikolopoulos T., Maragoudakis P., Segas J., Tzagaroulakis A., Ferekidis E. Intratympanic steroid treatment in idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss: a control study. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:940–945. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.03.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu Z., Dearman J.A., Cox B.C., Walters B.J., Zhang L., Ayrault O., Zindy F., Gan L., Roussel M.F., Zuo J. Age-dependent in vivo conversion of mouse cochlear pillar and Deiters’ cells to immature hair cells by Atoh1 ectopic expression. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:6600–6610. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0818-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Costa A., Sanchez-Guardado L., Juniat S., Gale J.E., Daudet N., Henrique D. Generation of sensory hair cells by genetic programming with a combination of transcription factors. Development. 2015;142:1948–1959. doi: 10.1242/dev.119149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xiang M., Gao W.Q., Hasson T., Shin J.J. Requirement for Brn-3c in maturation and survival, but not in fate determination of inner ear hair cells. Development. 1998;125:3935–3946. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.20.3935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harding G.W., Bohne B.A. Noise-induced hair-cell loss and total exposure energy: analysis of a large data set. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2004;115:2207–2220. doi: 10.1121/1.1689961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang J., Ruel J., Ladrech S., Bonny C., van de Water T.R., Puel J.-L. Inhibition of the c-Jun N-terminal kinase-mediated mitochondrial cell death pathway restores auditory function in sound-exposed animals. Mol. Pharmacol. 2007;71:654–666. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.028936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Coleman J.K.M., Kopke R.D., Liu J., Ge X., Harper E.A., Jones G.E., Cater T.L., Jackson R.L. Pharmacological rescue of noise induced hearing loss using N-acetylcysteine and acetyl-L-carnitine. Hear. Res. 2007;226:104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Woods C., Montcouquiol M., Kelley M.W. Math1 regulates development of the sensory epithelium in the mammalian cochlea. Nat. Neurosci. 2004;7:1310–1318. doi: 10.1038/nn1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.White P.M., Doetzlhofer A., Lee Y.S., Groves A.K., Segil N. Mammalian cochlear supporting cells can divide and trans-differentiate into hair cells. Nature. 2006;441:984–987. doi: 10.1038/nature04849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li H., Liu H., Heller S. Pluripotent stem cells from the adult mouse inner ear. Nat. Med. 2003;9:1293–1299. doi: 10.1038/nm925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li W., Wu J., Yang J., Sun S., Chai R., Chen Z.-Y., Li H. Notch inhibition induces mitotically generated hair cells in mammalian cochleae via activating the Wnt pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:166–171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415901112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cotanche D.A., Kaiser C.L. Hair cell fate decisions in cochlear development and regeneration. Hear. Res. 2010;266:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jawahar N., Meyyanathan S. Polymeric nanoparticles for drug delivery and targeting: a comprehensive review. Int. J. Health Allied Sci. 2012;1:217. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mudshinge S.R., Deore A.B., Patil S., Bhalgat C.M. Nanoparticles: emerging carriers for drug delivery. Saudi Pharm. J. 2011;19:129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Woodrow K.A., Cu Y., Booth C.J., Saucier-Sawyer J.K., Wood M.J., Saltzman W.M. Intravaginal gene silencing using biodegradable polymer nanoparticles densely loaded with small-interfering RNA. Nat. Mater. 2009;8:526–533. doi: 10.1038/nmat2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mohanraj V.J., Chen Y. Nanoparticles – a review. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2006;5:561–573. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vauthier C., Bouchemal K. Methods for the preparation and manufacture of polymeric nanoparticles. Pharm. Res. 2009;26:1025–1058. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9800-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yameen B., Choi W.I., Vilos C., Swami A., Shi J., Farokhzad O.C. Insight into nanoparticle cellular uptake and intracellular targeting. J. Control. Release. 2014;190:485–499. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cai H., Wen X., Wen L., Tirelli N., Zhang X., Zhang Y., Su H., Yang F., Chen G. Enhanced local bioavailability of single or compound drugs delivery to the inner ear through application of PLGA nanoparticles via round window administration. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2014;9:5591–5601. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S72555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ge X., Jackson R.L., Liu J., Harper E.A., Hoffer M.E., Wassel R.A., Dormer K.J., Kopke R.D., Balough B.J. Distribution of PLGA nanoparticles in chinchilla cochleae. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2007;137:619–623. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tamura T., Kita T., Nakagawa T., Endo T., Kim T.-S., Ishihara T., Mizushima Y., Higaki M., Ito J. Drug delivery to the cochlea using PLGA nanoparticles. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:2000–2005. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000180174.81036.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Youm I., Musazzi U.M., Gratton M.A., Murowchick J.B., Youan B.C. Label-free ferrocene-loaded nanocarrier engineering for in vivo cochlear drug delivery and imaging. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016;105:3162–3171. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2016.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Youm I., West M.B., Li W., Du X., Ewert D.L., Kopke R.D. siRNA-loaded biodegradable nanocarriers for therapeutic MAPK1 silencing against cisplatin-induced ototoxicity. Int. J. Pharm. 2017;528:611–623. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Panyam J., Zhou W.-Z., Prabha S., Sahoo S.K., Labhasetwar V. Rapid endo-lysosomal escape of poly(DL-lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles: implications for drug and gene delivery. FASEB J. 2002;16:1217–1226. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0088com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brown J.N., Miller J.M., Altschuler R.A., Nuttall A.L. Osmotic pump implant for chronic infusion of drugs into the inner ear. Hear. Res. 1993;70:167–172. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(93)90155-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Du X., Chen K., Kuriyavar S., Kopke R.D., Grady B.P., Bourne D.H., Li W., Dormer K.J. Magnetic targeted delivery of dexamethasone acetate across the round window membrane in guinea pigs. Otol. Neurotol. 2013;34:41–47. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318277a40e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sakamoto T., Nakagawa T., Horie R.T., Hiraumi H., Yamamoto N., Kikkawa Y.S., Ito J. Inner ear drug delivery system from the clinical point of view. Acta Otolaryngol. Suppl. 2010;130:101–104. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2010.486801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hirose Y., Sugahara K., Mikuriya T., Hashimoto M., Shimogori H., Yamashita H. Effect of water-soluble coenzyme Q10 on noise-induced hearing loss in guinea pigs. Acta Otolaryngol. 2008;128:1071–1076. doi: 10.1080/00016480801891694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen Z., Kujawa S.G., McKenna M.J., Fiering J.O., Mescher M.J., Borenstein J.T., Swan E.E., Sewell W.F. Inner ear drug delivery via a reciprocating perfusion system in the guinea pig. J. Control. Release. 2005;110:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kopke R.D., Jackson R.L., Li G., Rasmussen M.D., Hoffer M.E., Frenz D.A., Costello M., Schultheiss P., Van De Water T.R. Growth factor treatment enhances vestibular hair cell renewal and results in improved vestibular function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:5886–5891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101120898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cun D., Foged C., Yang M., Frøkjaer S., Nielsen H.M. Preparation and characterization of poly(DL-lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles for siRNA delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2010;390:70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]