Abstract

Background

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials examining the effect of psychosocial interventions on the quality of life of patients with colorectal cancer.

Methods

We searched the main health-related databases for relevant papers. Then, we examined the titles and abstracts of the retrieved papers, applying exclusion criteria to filter out irrelevant papers; a more in-depth filtering process was then conducted by reading the full texts. Eight studies remained at the end of this process. Next, we performed data extraction and assessed the methodological quality of the selected studies. This was followed by computation of effect sizes and the heterogeneity of the results, and then an assessment of the potential bias.

Results

The systematic review found that most of the interventions in these eight studies did not have a significant effect on quality of life. Meanwhile, the meta-analysis, the overall effect of psychosocial interventions at the post-intervention period was found to be statistically significant but small.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis provides evidence for the beneficial effect of face-to-face psychosocial interventions on the quality of life of colorectal cancer patients. It is, however, suggested that further studies be conducted on this topic to assess the roles of physical functioning and severity of symptoms before utilizing such face-to-face interventions.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12955-018-0943-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Psychosocial interventions, Quality of life, Meta-analysis

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a global concern and one of greatest causes of death in developed and developing countries. It is the third most common cancer afflicting both men and women, with 1.4 million cases and 693,900 deaths estimated to occur annually [1]. In recent decades, although the incidence rate has increased, CRC mortality rates have decreased in many countries [1, 2]. It is widely believed that regular screening and improved treatments are the main contributors to this decrease in mortality [3, 4].

Throughout the disease trajectory, cancer patients experience psychological distress, including depression and anxiety [5], which in turn lead to worsened quality of life [6]. Furthermore, undergoing surgical treatments such as stoma formation can decrease psychosocial health and quality of life even further, particularly in patients with CRC [7–10]. Both psychological distress and a lack of social support have significant negative impacts on the quality of life of patients with CRC. For example, one previous study found that psychological distress was a significant predictor of both the mental and physical health domains of quality of life [11]. Conversely, another study found that patients with greater social support had better quality of life at one year post-surgery [12]. These results suggest that implementing psychosocial interventions might be crucial for improving the quality of life of patients with CRC.

The term “psychosocial intervention” encompasses interventions that include psychological and social contents; specifically, “psychosocial” is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as “involving the influence of social factors of human interactive behavior.” Psychoeducational programs are frequently provided for cancer patients in an attempt to improve their quality of life and to provide them with further information on the various methods of coping with cancer that they can perform in daily life. These programs have shown a positive effect on health-related quality of life [13–15]. Over the last decade, various types of psychosocial interventions have been conducted with the aim of improving CRC patients’ quality of life. Literature reviews seeking to synthesize the evidence concerning the effects of such psychosocial interventions on the outcomes of patients with CRC were also rigorously conducted during this same period. These comprehensive reviews determined that various types of interventions, including home visits, telephone sessions, and individual/group sessions, clearly reduce psychological distress and increase quality of life [16].

Most recently, in 2017, a systematic review of 14 randomized controlled trials of psychosocial interventions for CRC patients was published [17]; however, this study did not include a meta-analysis, which would enable us to quantify the strength of the evidence from previous studies. This would have clear clinical implications for healthcare providers by enabling them to recognize which interventions are most effective. Since a meta-analysis provides more statistically robust and reliable findings [18], it can help healthcare providers choose more effective and practical interventions for use in the field.

Meta-analyses have been included in past studies investigating the effects of psychosocial interventions on cancer survivors’ quality of life, revealing that such psychosocial interventions have both short- (less than eight months) and long-term (greater than eight months) effects on quality of life [19] and that psychosocial intervention with durations of over 12 weeks are more effective than those with shorter durations [20]. However, to our knowledge, the effect of psychosocial interventions on the quality of life of CRC patients has not yet been thoroughly analyzed. The abovementioned meta-analyses aggregated all types of cancer patients in their analyses, and therefore the results may differ from those for patients with CRC.

Little is known about the effectiveness of a variety of psychosocial interventions. The aims of this study are to present the results of a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials examining the effects of psychosocial interventions on the quality of life of CRC patients.

Methods

Literature search

The present study was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The articles were identified using the main databases related to health, including PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, the Cochrane database, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and SCOPUS, with the search criteria set to identify English-language, peer-reviewed studies published between January 2000 and October 2016. We performed searches using the combinations of the following keywords and similar terms (consisting of MeSH and entry terms): “colorectal cancer,” “colorectal neoplasm,” “colorectal tumor,” “quality of life,” “wellbeing,” “psychological outcome,” “psychosocial therapy,” “psychosocial intervention,” “education,” “counseling,” and “behavioral therapy.” To avoid missing potentially applicable articles, comprehensive searches using these keywords and similar terms were conducted. The strategy was modified as appropriate for the different databases (see Additional file 1).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The primary inclusion criteria were being a randomized controlled trial of a psychosocial intervention and focusing on quality of life as the outcome. We defined psychosocial interventions as interventions involving psychological or social support. For the psychological support interventions, we selected cognitive behavioral therapy, psychotherapy, counseling, supportive therapy, and motivational interviewing as relevant interventions. For the social support intervention, we included social-skills training, which focuses on developing social networks and training to minimize social isolation or conflict (familial/work). Another eligibility criterion was that the interventions had to have been delivered by trained personnel such as nurses, allied healthcare workers, or psychologists. A wide range of intervention delivery methods were included in the analysis: group vs. individual-focused and telephone/web-based vs. face-to-face or hybrid.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) was not a randomized controlled trial; 2) did not measure quality of life as the outcome (e.g., studies that measured only psychological factors such as anxiety, depression, or stress were excluded); 3) did not use formal psychometric scales to assess quality of life; 4) unavailable full text; and 5) limited information for computing the common effect size.

Data extraction and quality assessment

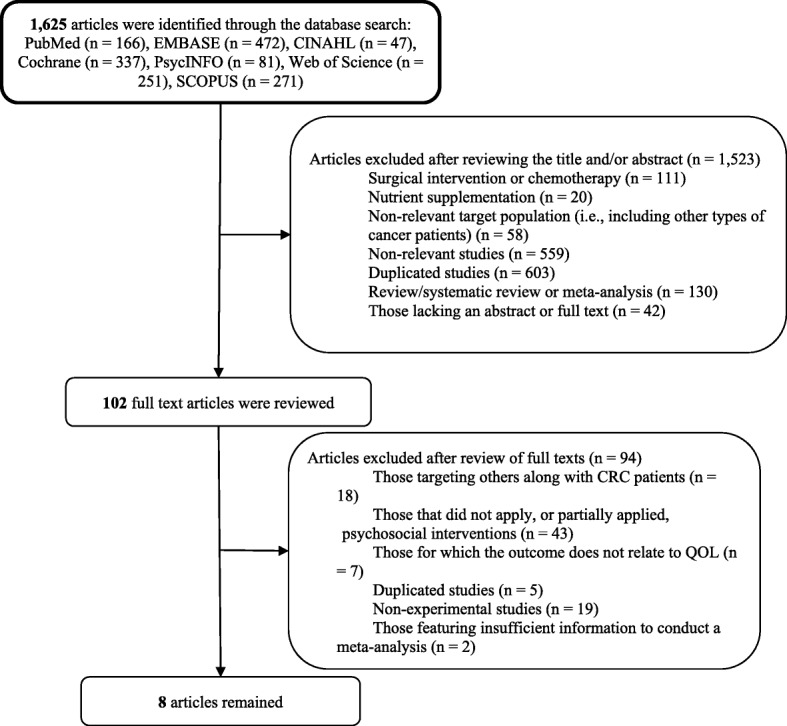

A total of 1625 articles were identified through the database search. Three authors then independently reviewed each title and abstract and compared their decisions; during this process, articles that used a less relevant study design (i.e., review papers) and those lacking abstracts or full texts (i.e., poster presentations) were excluded. Consequently, 102 full-text articles remained, and these advanced to the next stage of the filtering process, in which articles with meeting any of the following criteria were excluded: did not target patients with CRC only; did not apply, or only partially applied, psychosocial interventions; did not mention effects on quality of life in their outcomes; were duplicate studies; were non-experimental; and lacked sufficient information to facilitate a meta-analysis. Just eight studies advanced to the meta-analysis (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Plasma flow for literature search strategy

In the next stage, data regarding study design, participants, interventions, comparators, and outcomes were extracted using a predesigned data extraction form. Specifically, for study design, relevant data included the country in which the study took place, the sample size, and the timing of the follow-ups; data concerning participant characteristics included CRC diagnosis, gender, and age; data concerning intervention characteristics included information regarding components applied, personnel involved, and duration; and data concerning the outcomes included the means and standard deviations or number of events. In cases where published data was incomplete or unclear, the authors of the studies in question were contacted for clarification. All the above data were extracted independently by three reviewers, and any disagreements between two reviewers were resolved through discussion or by consulting the third reviewer.

Next, three reviewers (HS, YS, and HK) independently assessed methodological quality using the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias assessment tool [21]. This tool assesses risk as being high, low, or unclear for the following domains: random-sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, and selective reporting and blinding of participants and personnel (administering the intervention). Due to the nature of the studies analyzed, the latter domain was not assessed in this review. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or consultation with another reviewer (YL).

Statistical analysis

As there were variances in the values of the included studies, effect sizes were computed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software package Version 3.0 (trial). The effects of the psychosocial interventions were determined by applying Hedges’ g, which could be interpreted as small (g < 0.3), medium (g > 0.5), or large (g > 0.8) [22]. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using mean scores and standard deviations, change scores, or p- or t-values [23]. The heterogeneity of the results across studies was assessed using Q and I2 statistics, and any obvious heterogeneity was predefined as p < 0.05 in Q statistics or an I2 value of 50% or higher [24]; in cases where heterogeneity was found, a random-effects model was used.

Most of the studies had multiple outcomes; therefore, we calculated the overall effect size using the mean of the selected outcomes with a random-effects model, and then used a fixed-effects model to conduct subgroup analyses according to intervention type, length of the follow-ups implemented, and measurement tool. Next, potential publication bias was investigated by initially conducting a visual inspection of the funnel plots. Then, funnel plot asymmetry was tested using Egger’s test, and the trim and fill method was used to adjust for publication bias [25]. We also conducted sensitivity analysis to assess the influence of each study on the overall effect by removing one of the studies in each round.

Results

Characteristics and quality of included studies

Table 1 summarizes the descriptions of each selected study and the characteristics of the samples. Of the eight randomized controlled trials selected, which featured a cumulative total of 2117 patients, three and two studies were conducted in Australia and the United States, respectively, while the remaining three studies were performed in Hong Kong, Canada, and Denmark. The publishing years ranged from 2005 to 2016, with seven published in 2010 or later. Participants’ mean age ranged from 56.2 to 68.6 years, and women accounted for between 31.6 and 63% of the sample populations.

Table 1.

Description of studies and sample characteristics (n = 2117)

| Subjects | Intervention | Outcome (tool) | Main results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Carmack et al., 2011) in the US[27] | ∙Individuals with stage I, II, III colon or rectal cancer (n = 40: intervention n = 25 vs. control n = 15) ∙Mean age = 56.2 years ∙Women (63%) |

12 one-hour sessions over four months (nine weekly sessions, two bimonthly sessions, and one concluding session in month 4) | QOL (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) questionnaires) | For individuals in the intervention group, EORTC emotional functioning was not found to have significantly improved at two months, but had at four months. For the control group, EORTC was not significant at two or four months. |

| (Jefford et al., 2016) in Australia[48] | ∙Individuals with stage I, II, or III colon or rectal cancer (n = 217: survivor care n = 110 vs. normal care n = 107) ∙ Mean age = 62.1 years for the intervention group and 63.1 years for the control group ∙ Women (47.7% for the intervention group and 49.1 for the control group) |

Four main components: 1) an information package; 2) a nurse-led, face-to-face end-of-treatment session; 3) a tailored survivor care plan; and 4) nurse-led telephone follow-ups at one, three, and seven weeks after the first intervention session |

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer core questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-30) and CRC module (EORTC QLQ CR-29) | At two and six months post-baseline, all differences in QLO-C30 and QLQ C-29 between the two groups were small and not significant. |

| (Lee, Ho, & Chan, 2010) in Hong Kong[49] | ∙Patients with colorectal cancer (n = 166: intervention n = 84 vs. n = 82 control) ∙Mean age = 60 years (58.9 years for the intervention groups and 60.5 years for the control group) ∙Women (33.7 and 36.4% for the intervention groups and 31% for the control group) |

Participants in intervention received body-mind-spirit intervention for 15 h. Each group consisted of 10 to 12 members and met weekly for five weeks. | QOL was measured using the validated Chinese version of the SF-36 | No significant interaction effect (time × intervention) either in the intervention or control groups for SF-36 was found. |

| (Lepore, Revenson, Roberts, Pranikoff, & Davey, 2015) in the US[50] | ∙Patients diagnosed with stage I-III cancer of the colon or rectum and who had completed surgical treatment within the previous five years (n = 193: intervention n = 101 vs. control n = 92) ∙ Mean age = 54.4 years for the intervention group and 55.8 years for the control group ∙ Women (49.5% for the intervention group and 48.9 for the control group) |

Participants were asked to write for 15 min twice a week for two weeks about their deepest thoughts and feelings concerning their cancer, other stressors, or both. | Five domains of the Cancer Quality of Life questionnaire (QLQ-30) developed by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer | There was no statistical difference between the intervention and control groups in terms of: global quality of life; physical functioning; role functioning; emotional functioning; cognitive functioning; or social functioning. |

| (Ohlsson-Nevo et al., 2016) in Sweden[13] | ∙Patients treated surgically for colon, rectal, or anal cancer (n = 86: intervention n = 47 vs. control n = 39) ∙ Mean age = 66.1 years for the intervention group and 65.9 years for the control group ∙ Women (41.7% for the intervention group and 31.6% for the control group) |

The program included seven meetings that each featured 60-min informational lectures. Topics included colorectal cancer, music and relaxation, the operating theatre, the importance of engaging in physical activities, the meaning of food, crisis and crisis intervention, and patients’ organization | SF-36 were measured at baseline, one, six, and 12 months after the end of the program | ∙The intervention group reported significantly better overall mental health status than the control at one month after the end of the program. The between-group difference was of moderate size. ∙No statistically significant between-group differences in overall physical health status were observed at any of the follow-up assessments, but the effect sizes indicated that the intervention group had a small effect after six and 12 months. ∙Within the intervention group, significant improvements in both PCS and MCS were found: PCS; 0-one month, zero–six months, zero–12 months; MCS zero–, zero–six months, zero–12 months. |

| (Ross, Thomsen, Karlsen, Boesen, & Johansen, 2005) in Denmark[51] | ∙ Colorectal cancer patients (n = 249; intervention n = 125 vs. control n = 124) ∙Median age = 68.8 years for the intervention group and 68.1 years for the control group ∙Women (50% for the intervention group and 53% for the control groups) |

Over the first two years after discharge, the intervention group received 10 home visits from a project nurse or a medical doctor. These visits were aimed at providing emotional and information and support and encouraging the patients to make use of their own social networks to cope with the disease. |

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) quality of life core questionnaire QOQ-C30, and EORTC QLQ-CR38 for the specific colorectal cancer module | ∙At the three-month follow-up, following the most intensive period of intervention, the only significant difference between the intervention and control groups was symptoms of fatigue. ∙Also at the three-month follow-up, all 15 subscales/items of EORTC QLQ-C30 were in favor of the intervention group, but this pattern did not persist during the full two-year period of follow-ups and was not observed on the colorectal cancer module (EORTC QLQ-CR38). ∙The intervention had no overall effect on the level of QOL. Further, no differential development with time during follow-up was observed on the employed scales, except for a differential development with time in the groups for social functioning: at the first follow-up interview the control group had a lower level of social functioning than the intervention group, but this difference diminished with time. |

| (Young et al., 2013) in Australia [52] | ∙Adult patients undergoing surgery for primary colorectal cancer (n = 756; intervention n = 387 vs. control n = 369) ∙Mean age = 68.6 years for the intervention group and 67 years for the control group ∙Women (43.2% for the intervention group and 45.8% for the control group) |

This intervention involved no face-to-face contact. It consisted of five scheduled, structured telephone calls on days three and 10 and then at one, three, and six months after hospital discharge. The phone conversations were based on the findings of a clinical audit of the postoperative needs of patients with colorectal cancer. | Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Colorectal (FACT-C) | There was no significant difference in QOL between the groups at any follow-up time point: one month; three months; or six months. |

| (Hawkes, Pakenham, Chambers, Patrao, & Courneya, 2014) in Australia[26] | ∙Adult patients with a histologically confirmed diagnosis of primary colorectal cancer within the previous 12 months (n = 410: intervention n = 205 vs. control n = 205) ∙Mean age = 64.9 years for the intervention group and 67.8 years for the control group ∙Women (48.3% for the intervention group and 43.9% for the control group) |

This intervention featured four components: 1) 11 telephone-delivered health coaching sessions over six months; 2) a participant handbook; 3) regular motivational postcards; and 4) a pedometer. Both groups also received a quarterly study newsletter |

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Colorectal (FACT-C, version 4) was used to measure QOL at baseline, six months and 12 months. | ∙In the intervention group, there significant improvements in quality of life were observed at six and 12 months; physical well-being at six and 12 months; social well-being at six months; emotional well-being at six and 12 months; functional well-being at six and 12 months; and additional well-being at six and 12 months. ∙The intervention group showed significantly higher improvements in physical well-being at six and 12 months than the control group. **However, total quality of life score and subscales were also significantly improved in the control group** |

Various types of psychosocial interventions were used, including coaching, telephone interviews, face-to-face counseling, and meetings. The instruments used to measure quality of life also varied, but half of the studies utilized questionnaires developed by the European Organization for Research and Treatment for Cancer. The interventions were delivered to the patients repeatedly from baseline to six months; to examine the long-term effect of the intervention, some studies measured the outcome after the intervention was complete. Finally, for most studies the effect of psychosocial interventions on quality of life was not found to be statistically significant; nevertheless, slight improvements in quality of life were detected in all intervention groups.

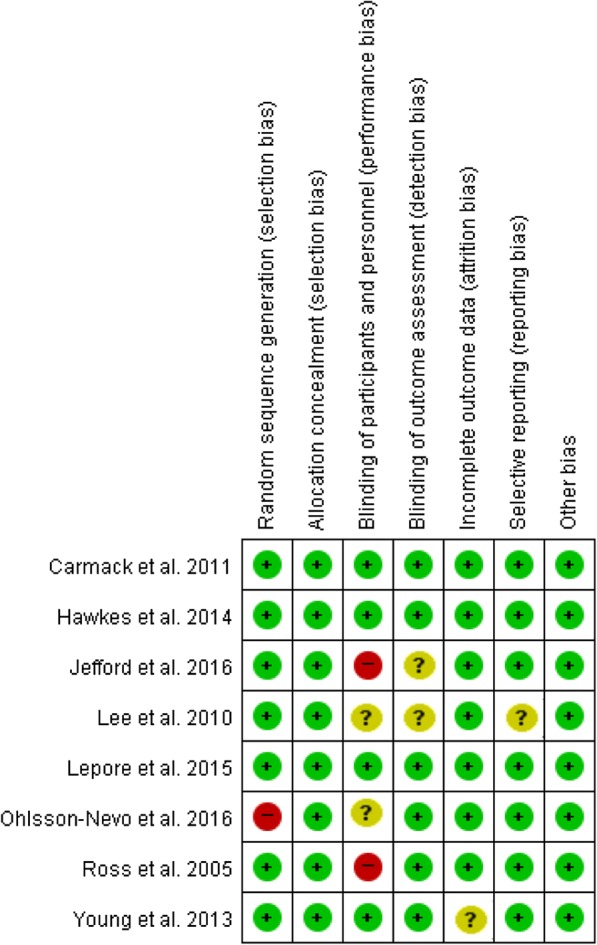

We evaluated the overall risk of bias as low. Regarding the individual studies, Fig. 2 shows that the majority of the studies possessed a low risk of bias. Specifically, three studies were evaluated as low risk in all criteria, while the scores for the other studies ranged from four to six.

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias for each included study

Meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions

Overall effects

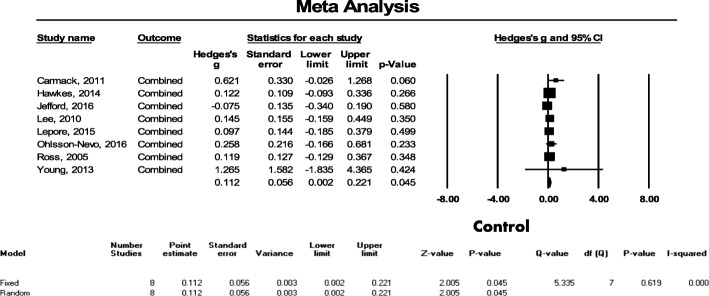

Eight studies featuring a total of 2117 patients were evaluated to examine the effect of psychosocial interventions on the quality of life of CRC patients. In this evaluation, the overall effect of the post-intervention measurement was found to indicate that interventions with no heterogeneity (I2 = 0.0%) and a small effect (Hedges’ g = 0.145, SE = 0.056, 95% CI = 0.035–0.254, p = 0.009) have a statistically significant benefit on quality of life (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effect size of psychosocial interventions on overall quality of life

Further, the funnel plots were found to be asymmetric for all eight outcomes and the Egger’s test was found to be statistically significant (p = 0.012); however, after three studies were filled using the trim and fill method, the adjusted point estimate was 0.143, which indicates that this had no significant effect on the results (Additional file 2). Next, we performed a sensitivity analysis and found that the overall effect size (from 0.131 to 0.155) did not significantly change when any one of the eight studies selected was removed, which means that each individual study had little impact on the overall outcome (Additional file 3).

Subgroup analysis

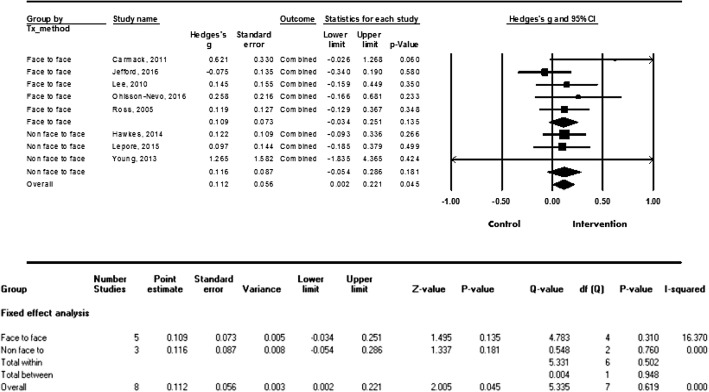

Since the types and durations of each psychosocial intervention varied, we conducted subgroup analyses to provide more practical evidence. To examine the effectiveness of the specific types of interventions, we categorized them into face-to-face versus non-face-to-face interventions. Five studies used the face-to-face type, and showed a small effect size (g = 0.160, SE = 0.073, 95% CI = 0.018–0.303, p = 0.028). The remaining three studies used the non-face-to-face type, and were not significantly associated with improvements in quality of life (g = 0.116, SE = 0.087, 95% CI = − 0.048–0.293, p = 0.158) (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Effect size by types of intervention (face-to-face vs. non-face-to-face)

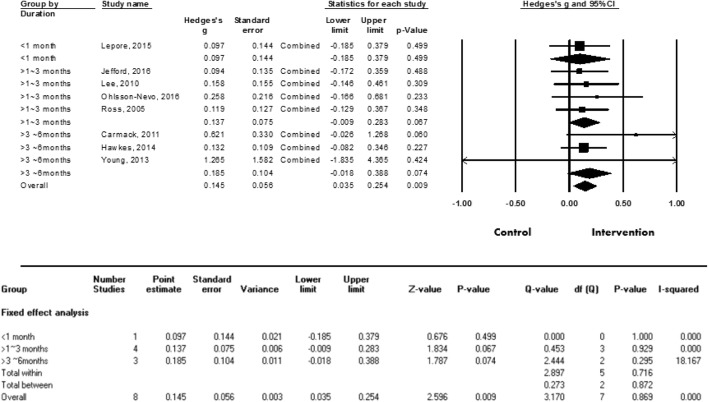

To determine the effective intervention duration, the time periods over which the interventions were delivered were categorized into three levels: less than a month; between one and three months; and over three months. As seen in Fig. 5, Hedges’ g was 0.097 for less than one month, 0.137 for between one month and less than three months, and 0.185 for over three months. These findings indicate that the longer the duration of the intervention, the larger the effect size; however, the associations were still not statistically significant (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Effect size of meta-analysis on quality of life

Discussion

To our knowledge, the current study is the first meta-analysis to provide comprehensive evidence for the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions on the quality of life of CRC patients. A total of eight randomized controlled trials (2117 patients overall) evaluating the application of psychosocial interventions for CRC patients were systematically reviewed, but only one of these studies, that of Hawkes et al. [26], identified a significant improvement in the quality of life of its intervention group.

Our study is comparable with a recent systematic review of 14 randomized controlled trials [17], which showed that three trials found an intervention effect for multiple mental health outcomes, while eight studies exhibited no effect. One clear similarity between our study and that of Mosher et al. is the inclusion of Carmack et al.’s study [27]. Specifically, Carmack et al.’s study [27] revealed that global symptom distress and depression were reduced as a result of their intervention, but quality of life did not improve. In contrast, one important difference between our study and that of Mosher et al. [17] is that they defined the term “psychosocial intervention” in a more comprehensive manner. They stated that it concerns psychotherapy and educational programs, and the researchers also examined both psychosocial factors and quality of life as outcomes, which—along with the use of a greater number of keywords—resulted in a greater number of studies being included.

Although most of the interventions evaluated in the included studies did not have a significant effect on quality of life, the meta-analysis showed that the overall effect at the post-intervention measurement was statistically significant and had a small effect size. This finding is consistent with that of another meta-analysis, which stated that various types of psycho-oncological interventions have significant, small-to-medium beneficial effects on emotional distress and quality of life in adult cancer patients [28]. In contrast, in other meta-analysis studies, such as one that investigated the effectiveness of exercise on the quality of life of CRC patients and one that examined the effect of behavior techniques on the quality of life of breast cancer patients, the respective interventions had no significant short-term effect on quality of life [29, 30]. Although the interventions used in the abovementioned studies might not be comparable (psychosocial vs. exercise), the findings still suggest that psychosocial interventions make a greater contribution to improving quality of life. Considering this, in future studies, various types of interventions should be conducted in order to investigate their effectiveness on quality of life.

Future clinical implication and research directions

The patients with colorectal cancer more frequently experience psychological distress than do those with other types of cancer [31] and experience social difficulties [32]. Based on our findings, we certainly have strong clinical implications in planning more effective psychosocial interventions. In the current meta-analysis, face-to-face intervention methods showed a statistically significant effect on quality of life, whereas the non-face-to-face intervention, such as email- or telephone-based approaches, did not. Face-to-face interventions appear to enhance the development of therapeutic relationships, thereby leading to an increase in patients’ degree of adherence to healthcare providers’ recommendations. This finding was supported by those of previous studies: compared to Internet-based interventions, face-to-face interventions showed a larger effect size for reducing depressive symptoms [33, 34]. Thus, it is worth using face-to-face methods in clinical settings and they should be considered as the key component of psychosocial interventions for the colorectal cancer survivors.

However, the disadvantages of face-to-face interventions are that they can be time consuming and costly for the patient. As a result, non-face-to-face interventions have been widely used over the past decade. In recent years, Internet/web-based studies have been employed to provide more tailored psychosocial interventions for patients with cancer [35]. Such web-based psychoeducational interventions have been shown to increase the quality of life of family caregivers as well as cancer patients [36], and the development of computer-tailored physical activity interventions for prostate cancer or CRC patients and survivors has now been proposed [37].

In the current research, it was found that the main purpose of psychosocial interventions for colorectal cancer survivors was to improve confidence for self-care through coaching and empowerment [38, 39]. Currently, various types of face-to-face coaching using smart technology have been developed including telephone, video conference, instant message, and email [40, 41]. In addition, the use of virtual reality and augmented reality might be a good alternative to face-to-face interventions because they give the user interactive and instant feedback. For example, virtual reality programs were effective for improving the health-related quality of life of older women [42]. Therefore, it might be beneficial for CRC patients to receive Internet-based, web-based, or virtual reality psychosocial interventions in the future.

The application of smart technology can be a convenient and cost effective method, but the effectiveness should not be compromised for efficiency [43]. As in traditional face-to-face coaching, it is also important to consider the patient’s motivation and level of acceptance of the relationship and establish a relationship based on trust, which is development-oriented, when using smart technology [41, 44].

However, it may not be always possible to utilize those technological resources. In addition, healthcare providers or patients may worry about the technology-based interaction and lose the opportunity to form a relationship or reduce the quality of the relationship. Thus, it is recommended that the healthcare providers use the traditional face-to-face coaching method in an initial psychosocial intervention to develop rapport and interaction with the patients [41]. de Zwaan et al. [45] indicated that the face-to-face therapy was more effective for early treatment than Internet-based guided self-help. Therefore, our finding may guide healthcare professionals in the field by suggesting the use of the face-to-face method at the initial phase of the psychosocial intervention.

We found that the longer the duration of the intervention, the greater the effect size (although this was not statistically significant). This finding is consistent with those of other meta-analysis studies on cancer patients. For example, previous studies have found that longer interventions produce more sustained effects [20, 28], while others found that longer periods of exercise-intervention time are effective for improving quality of life [46]. However, this result should be interpreted cautiously, since only the intervention duration was included in the analysis and the magnitude of the interventions in question (i.e., the frequency and amount of intervention) was not considered. Therefore, further study is required to examine the effect size in terms of intervention duration and strength. Furthermore, it is necessary to conduct larger randomized controlled trials for longer durations in the future in order to identify the most effective time period for the improvement of quality of life.

To increase the level of evidence for the current meta-analysis, only randomized controlled trial studies were included and the quality assessment was undertaken using the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool. First, at the random-sequence-generation domain, as the randomization methods were clearly described in the text, a total of seven studies were evaluated as having a low risk of bias. As for incomplete outcome data, most studies were graded as having a low risk of bias with low dropout rates. Next, regarding the blinding of participants and personnel, two studies were evaluated as having a high risk of bias. Finally, for blinding the outcome assessment, six studies were rated as having a low risk of bias. It should be noted that the use of inadequate blinding may produce detection bias, which means that the measured values might not reflect reality. Considering the above, future research should underline allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, and outcome assessors in order to obtain more reliable conclusions.

Study limitations

There are several limitations in the current meta-analysis. First, although we used thorough search strategies to minimize inclusion and publication bias, there is still the possibility that some studies were missed. Second, the number of studies included in the current meta-analysis is relatively small, and the characteristics of the patients in each study were also heterogeneous; therefore, it may be premature to generalize these findings. It is necessary to focus on delineating the key characteristics of the psychosocial interventions found to be effective by using a prospective design. Third, the current study applied the total score for quality of life in the meta-analysis, since the instruments used to measure quality of life varied for each study. Psychosocial interventions might be more effective for certain subdomains of quality of life. Thus, future studies are required to investigate the effect of the interventions on specific aspects of the quality of life construct. Although the majority of studies measured the outcomes multiple times through follow-up assessments, longitudinal studies over the course of randomized controlled trials were found to be insufficient. As such, future studies should employ a larger randomized controlled trial using a longitudinal study design.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis provides evidence for the beneficial effect of face-to-face-based psychosocial interventions on the quality of life of CRC patients. Of course, it is still premature to generalize these findings, as the identified effect size was small. Given that quality of life changes with time and emphasizes the importance of personal growth [47], it may take time to fully detect improvements in quality of life. Further, the quality of life of cancer patients may also depend on the prognosis during the disease trajectory. To improve quality of life for CRC patients, therefore, further studies should assess physical functioning or the severity of symptoms before face-to-face intervention methods are utilized.

Additional files

Search strategies for used database. (DOCX 21 kb)

Funnel plot of Hedge’s g against its standard error for quality of life using trim and fill method. (DOCX 126 kb)

Overall effect size when one study was removed. (DOCX 25 kb)

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (NRF-2015R1C1A1A01054200) and supported by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE) and Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT) through the International Cooperative R&D program.

Availability of data and materials

All data supporting our findings are contained within the manuscript and the authors can be contacted at lyj@pusan.ac.kr for further clarification if required.

Abbreviations

- CI

Confidence interval

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

Authors’ contributions

HS and YS searched the literature, conceived and designed the study, acquired data, and drafted the manuscript. HK and YL analyzed the data, and YL interpreted the data and helped to revise the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12955-018-0943-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Heesook Son, Email: hson@cau.ac.kr.

Youn-Jung Son, Email: yjson@cau.ac.kr.

Hyerang Kim, Email: hkim167@hotmail.com.

Yoonju Lee, Email: lyj@pusan.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oh C-M, Won Y-J, Jung K-W, Kong H-J, Cho H, Lee J-K, et al. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2013. Cancer Res Treat. 2016;48(2):436–450. doi: 10.4143/crt.2016.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosetti C, Levi F, Rosato V, Bertuccio P, Lucchini F, Negri E, et al. Recent trends in colorectal cancer mortality in Europe. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(1):180–191. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edwards BK, Ward E, Kohler BA, Eheman C, Zauber AG, Anderson RN, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2006, featuring colorectal cancer trends and impact of interventions (risk factors, screening, and treatment) to reduce future rates. Cancer. 2010;116(3):544–573. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrington CB, Hansen JA, Moskowitz M, Todd BL, Feuerstein M. It’s not over when it's over: long-term symptoms in cancer survivors—a systematic review. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2010;40(2):163–181. doi: 10.2190/PM.40.2.c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elliott J, Fallows A, Staetsky L, Smith PWF, Foster CL, Maher EJ, et al. The health and well-being of cancer survivors in the UK: findings from a population-based survey. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(S1):S11–S20. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alacacioglu A, Binicier O, Gungor O, Oztop I, Dirioz M, Yilmaz U. Quality of life, anxiety, and depression in Turkish colorectal cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18(4):417–421. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0679-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medeiros M, Oshima CTF, Forones NM. Depression and anxiety in colorectal cancer patients. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2010;41(3):179–184. doi: 10.1007/s12029-010-9132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mosher CE, Winger JG, Given BA, Helft PR, O’Neil BH. Mental health outcomes during colorectal cancer survivorship: a review of the literature. Psychooncology. 2016;25(11):1261–1270. doi: 10.1002/pon.3954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsunoda A, Nakao K, Hiratsuka K, Yasuda N, Shibusawa M, Kusano M. Anxiety, depression and quality of life in colorectal cancer patients. Int J Clin Oncol. 2005;10(6):411–417. doi: 10.1007/s10147-005-0524-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim Y, van Ryn M, Jensen RE, Griffin JM, Potosky A, Rowland J. Effects of gender and depressive symptoms on quality of life among colorectal and lung cancer patients and their family caregivers. Psychooncology. 2015;24(1):95–105. doi: 10.1002/pon.3580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzalez-Saenz de Tejada M, Bilbao A, Bare M, Briones E, Sarasqueta C, Quintana J, et al. Association of social support, functional status, and psychological variables with changes in health-related quality of life outcomes in patients with colorectal cancer. Psychooncology. 2016;25(8):891–897. doi: 10.1002/pon.4022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohlsson-Nevo E, Karlsson J, Nilsson U. Effects of a psycho-educational programme on health-related quality of life in patients treated for colorectal and anal cancer: a feasibility trial. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2016;21:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott DA, Mills M, Black A, Cantwell M, Campbell A, Cardwell CR, et al. Multidimensional rehabilitation programmes for adult cancer survivors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;3:CD007730. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007730.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strong V, Waters R, Hibberd C, Murray G, Wall L, Walker J, et al. Management of depression for people with cancer (SMaRT oncology 1): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9632):40–48. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60991-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoon LS, Chi Sally CW, Hong-Gu H. Effect of psychosocial interventions on outcomes of patients with colorectal cancer: a review of the literature. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17(6):883–891. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mosher CE, Winger JG, Given BA, Shahda S, Helft PR. A systematic review of psychosocial interventions for colorectal cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(7):1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3693-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tourani S, Behzadifar M, Martini M, Aryankhesal A, Taheri Mirghaed M, Salemi M, et al. Health-related quality of life among healthy elderly Iranians: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16:18. doi: 10.1186/s12955-018-0845-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Osborn RL, Demoncada AC, Feuerstein M. Psychosocial interventions for depression, anxiety, and quality of life in cancer survivors: meta-analyses. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006;36(1):13–34. doi: 10.2190/EUFN-RV1K-Y3TR-FK0L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rehse B, Pukrop R. Effects of psychosocial interventions on quality of life in adult cancer patients: meta analysis of 37 published controlled outcome studies. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;50(2):179–186. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00149-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hedges LV. Distribution theory for Glass's estimator of effect size and related estimators. J Educ Behav Stat. 1981;6(2):107–128. doi: 10.3102/10769986006002107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hilsdale: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huedo-Medina TB, Sánchez-Meca J, Marín-Martínez F, Botella J. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychol Methods. 2006;11(2):193. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot–based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hawkes AL, Pakenham KI, Chambers SK, Patrao TA, Courneya KS. Effects of a multiple health behavior change intervention for colorectal cancer survivors on psychosocial outcomes and quality of life: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Behav Med. 2014;48(3):359–370. doi: 10.1007/s12160-014-9610-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carmack CL, Basen-Engquist K, Yuan Y, Greisinger A, Rodriguez-Bigas M, Wolff RA, et al. Feasibility of an expressive-disclosure group intervention for post-treatment colorectal cancer patients. Cancer. 2011;117(21):4993–5002. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faller H, Schuler M, Richard M, Heckl U, Weis J, Küffner R. Effects of psycho-oncologic interventions on emotional distress and quality of life in adult patients with cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(6):782–793. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.8922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cramer H, Lauche R, Klose P, Dobos G, Langhorst J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of exercise interventions for colorectal cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2014;23(1):3–14. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duijts SF, Faber MM, Oldenburg HS, van Beurden M, Aaronson NK. Effectiveness of behavioral techniques and physical exercise on psychosocial functioning and health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients and survivors—a meta-analysis. Psychooncology. 2011;20(2):115–126. doi: 10.1002/pon.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taghizadeh A, Pourali L, Vaziri Z, Saedi HR, Behdani F, Amel R. Psychological distress in Cancer patients. Middle East J Cancer. 2018;9(2):143–149. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wright P, Downing A, Morris EA, Corner JL, Richards MA, Sebag-Montefiore D, et al. Identifying social distress: a cross-sectional survey of social outcomes 12 to 36 months after colorectal Cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(30):3423–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.6129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagner B, Horn AB, Maercker A. Internet-based versus face-to-face cognitive-behavioral intervention for depression: a randomized controlled non-inferiority trial. J Affect Disord. 2014;152:113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johansson R, Andersson G. Internet-based psychological treatments for depression. Expert Rev Neurother. 2012;12(7):861–869. doi: 10.1586/ern.12.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Willems RA, Bolman CA, Mesters I, Kanera IM, Beaulen AA, Lechner L. Short-term effectiveness of a web-based tailored intervention for cancer survivors on quality of life, anxiety, depression, and fatigue: randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2017;26(2):222–230. doi: 10.1002/pon.4113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Northouse L, Schafenacker A, Barr KL, Katapodi M, Yoon H, Brittain KA. Tailored web-based psycho-educational intervention for cancer patients and their family caregivers. Cancer Nurs. 2014;37(5):321–330. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Golsteijn R, Bolman C, Volders E, Peels D, Vries H, Lechner L. Development of a computer-tailored physical activity intervention for prostate and colorectal cancer patients and survivors: OncoActive. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):446. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3397-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reb A, Ruel N, Fakih M, Lai L, Salgia R, Ferrell B, et al. Empowering survivors after colorectal and lung cancer treatment: pilot study of a self-management survivorship care planning intervention. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2017;29:125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wagland R, Fenlon D, Tarrant R, Howard-Jones G, Richardson A. Rebuilding self-confidence after cancer: a feasibility study of life-coaching. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:651–659. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2399-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moreme. White Paper on Virtual Coaching and Mentoring: The value of coaching and mentoring over distance. 2013. https://www.moreme.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/White-paper-Virtual-Coaching-Final.pdf.

- 41.Rossett A, Marino G. If coaching is good, then e-coaching is. Training Development. 2005;59:46–49. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee M, Son J, Kim J, Yoon B. Individualized feedback-based virtual reality exercise improves older. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;61(2):154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pascal A, Sass M, Gregory JB. I’m only human: the role of technology in coaching. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research. 2015;67(2):100–109. doi: 10.1037/cpb0000025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gregory JB, Levy PE. Employee coaching relationships: enhancing construct clarity and measurement. Coaching: An Int J Theory, Res Practice. 2010;3:109–123. [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Zwaan M, Herpertz S, Zipfel S, Svaldi J, Friederich HC, et al. Effect of internet-based guided self-help vs individual face-to-face treatment on full or Subsyndromal binge eating disorder in overweight or obese patients: the INTERBED randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(10):987–995. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ferrer RA, Huedo-Medina TB, Johnson BT, Ryan S, Pescatello LS. Exercise interventions for cancer survivors: a meta-analysis of quality of life outcomes. Ann Behav Med. 2011;41(1):32–47. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9225-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Calman KC. Quality of life in cancer patients--an hypothesis. J Med Ethics. 1984;10(3):124–127. doi: 10.1136/jme.10.3.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jefford M, Gough K, Drosdowsky A, Russell L, Aranda S, Butow P, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a nurse-led supportive care package (SurvivorCare) for survivors of colorectal cancer. Oncologist. 2016;21(8):1014–1023. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee A, Ho J, Chan C. Efficacy of psychosocial intervention in improving quality. Hong Kong Med J. 2010;16(3):20–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lepore SJ, Revenson TA, Roberts KJ, Pranikoff JR, Davey A. Randomised controlled trial of expressive writing and quality of life in men and women treated for colon or rectal cancer. Psychol Health. 2015;30(3):284–300. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2014.971798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ross L, Thomsen BL, Karlsen RV, Boesen EH, Johansen C. A randomized psychosocial intervention study on the effect of home visits on the well-being of Danish colorectal cancer patients-the INCA project. Psychooncology. 2005;14(11):949–961. doi: 10.1002/pon.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Young JM, Butow PN, Walsh J, Durcinoska I, Dobbins TA, Rodwell L, et al. Multicenter randomized trial of centralized nurse-led telephone-based care coordination to improve outcomes after surgical resection for colorectal cancer: the CONNECT intervention. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(28):3585–3591. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Search strategies for used database. (DOCX 21 kb)

Funnel plot of Hedge’s g against its standard error for quality of life using trim and fill method. (DOCX 126 kb)

Overall effect size when one study was removed. (DOCX 25 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting our findings are contained within the manuscript and the authors can be contacted at lyj@pusan.ac.kr for further clarification if required.