Abstract

Background

Airway epithelium is the primary target for pathogens. It functions not only as a mechanical barrier, but also as an important sentinel of the innate immune system. However, the interactions and processes between host airway epithelium and pathogens are not fully understood.

Results

In this study, we identified responses of the human airway epithelium cells to respiratory pathogen infection. We retrieved three mRNA expression microarray datasets from the Gene Expression Omnibus database, and identified 116 differentially expressed genes common to all three datasets. Gene functional annotations were performed using Gene Ontology and pathway analyses. Using protein-protein interaction network analysis and text mining, we identified a subset of genes functioned as a group and associated with infection, inflammation, tissue adhesion, and receptor internalization in infected epithelial cells. These genes were further identified in BESE-2B cells in response to Talaromyces marneffei by Real-Time quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR). In addition, we performed an in silico prediction of microRNA-target interactions and examined our findings.

Conclusions

Using bioinformatics analysis, we identified several genes that may serve as biomarkers for the diagnosis or the surveillance of early respiratory tract infection, and identified additional genes and miRNAs that warrant further fundamental experimental research.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12866-018-1187-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Microarray analysis, Bioinformatics analysis, Respiratory pathogen, Human airway epithelial cell, Biomarker

Background

Respiratory tract infections are common diseases caused by a number of diverse pathogens. These diseases are serious public health concerns globally and pose significant challenges for the World Health Organization. Although treatment using potent anti-infection drugs and effective vaccines has greatly reduced mortality worldwide, respiratory tract infections remain a leading cause of death, in particular, for developing countries [1]. In 2015, there were 17.2 billion cases of upper respiratory infections [2]. A respiratory tract infection is a major risk to patients with chronic respiratory diseases, such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, and bronchiectasis. Infections caused by viral and/or bacterial pathogens exacerbate chronic respiratory diseases [3].

The airway epithelium is an extremely important barrier against respiratory pathogens. It covers a large surface area and is the primary target for respiratory pathogens [4]. In addition to acting as a natural barrier, recent studies found that airway epithelium functions as an important sentinel of the innate immune system against pathogens [5]. Interactions between epithelial cells and pathogens are inherently complex and encompass many different factors, including adhesion, internalization, and induction of the immune response [6]. In addition to being able to invade epithelial cells, some pathogens are capable of reproducing within infected cells, and in avoiding detection by the host immune system [7]. Therefore, prevention of pathogens from invading airway epithelial cells is crucial for the prophylaxis and treatment of respiratory infections. In the present study, we investigated interactions between airway epithelium cells and respiratory pathogens to better understand the underlying pathogenesis. Our findings may provide improved prophylaxis, surveillance, earlier accurate diagnosis, and better treatments.

Currently, high-throughput technologies such as microarrays and next-generation sequencing combined with bioinformatics analysis enable the generation and analysis of very large datasets, including mRNA, miRNA, and long non-coding RNA expression profiles, and DNA methylation. Such datasets are available in public archives such as the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). In this study, we retrieved three datasets of mRNA expression microarrays from GEO, and using bioinformatics analysis, we identified a group of genes as biomarkers in airway epithelial cells response to infection by respiratory pathogens, and we also identified several candidate targets for further fundamental experimental research.

Results

Microarray datasets

The mRNA expression profile datasets GSE3397 (Additional file 1), GSE6802 (Additional file 2), and GSE48466 (Additional file 3) were generated using the GPL570, GPL571 and GPL570 microarray platform at Duke University Medical Center, the Technical University Munich, and the University of Louisville, respectively. Thirty-five samples were used consisting of 10 samples of normal human bronchial epithelial cells and 25 samples of human bronchial epithelial cells exposed to the H1N1 influenza virus, the respiratory syncytial virus, Staphylococcus aureus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Table 1).

Table 1.

Microarray datasets of mRNA expression profiles

| Dataset | Organization | Platform | Sample (n) | Pathogen | time point (hours) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Treated | |||||

| GSE3397 | Duke University Medical Center | GPL570 | 4 | 8 | Respiratory syncytial virus(Long strain/lot 15D) [16] | 4 and 24 |

| GSE6802 | Technical University Munich | GPL571 | 3 | 8 | Respiratory syncytial virusstrain A2,Staphylococcus aureus(ATCC 29213), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa(ATCC 27853) [17] | 4 |

| GSE48466 | University of Louisville | GPL570 | 3 | 9 | H1N1 influenza virus(A/Kentucky/180/2010, A/Kentucky/136/2009, and A/Brisbane/59/2007) [18] | 36 |

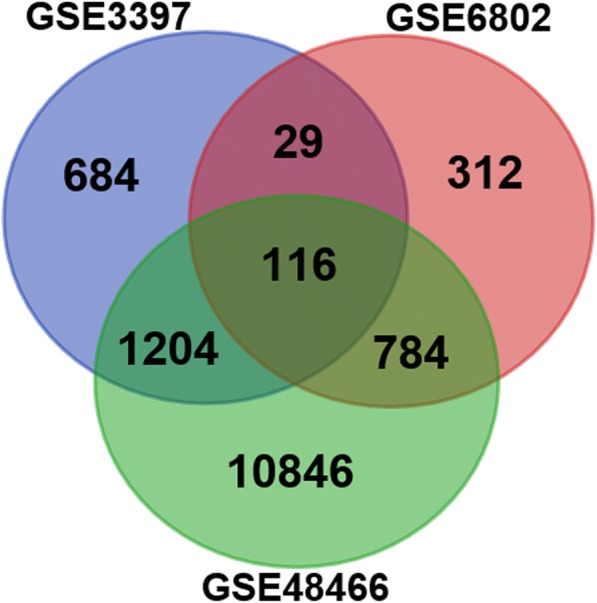

Differentially expressed genes

Using GEO2R, we identified 2033, 1241, and 12,950 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between normal and infected airway epithelial cells from the GSE3397, GSE6802, and GSE48466 datasets, respectively. We found that 116 genes were differentially expressed in all three datasets (Fig. 1). This set of 116 genes underwent further evaluation.

Fig. 1.

DEGs in three mRNA microarray datasets identified using GEO2R (P < 0.05). DEGs between normal and infected airway epithelial cells from the GSE3397 (n = 2033), GSE6802 (n = 1241), and GSE48466 (n = 12,950) datasets were identified, and 116 genes were differentially expressed in all three datasets

Functional annotations

This subset of 116 genes was uploaded to DAVID database for biological and functional assessments, and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis. Using Gene Ontology (GO) analysis, we found that these DEGs were usually involved in one of the following 10 biological processes: regulation of foam cell differentiation, regulation of tyrosine phosphorylation of the STAT protein, myeloid leukocyte differentiation, regulation of the JAK-STAT cascade, response to cytokine stimulus, myeloid cell differentiation, cAMP-mediated signaling, anti-apoptosis, ectoderm development and tissue morphogenesis (Table 2). We found that the most significantly enriched pathways were the ubiquitin mediated proteolytic pathway, NOD-like receptor (NLR) signaling pathway, and the apoptosis pathway (Table 3).

Table 2.

Top 10 enrichment biological processes of the 116 DEGs

| ID | Function | Gene | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| GO:0010743 | regulation of foam cell differentiation | CSF2, CSF1, NFKBIA | 0.01 |

| GO:0042509 | regulation of tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT protein | CSF2, NF2, IL6ST | 0.02 |

| GO:0002573 | myeloid leukocyte differentiation | CSF2, CSF1, CASP8 | 0.02 |

| GO:0046425 | regulation of JAK-STAT cascade | CSF2, NF2, IL6ST | 0.02 |

| GO:0034097 | response to cytokine stimulus | IL6ST, CASP8, PML, SERPINA1 | 0.01 |

| GO:0030099 | myeloid cell differentiation | CSF2, CSF1, CASP8, PML | 0.02 |

| GO:0019933 | cAMP-mediated signaling | OPRM1, EIF4EBP2, PTGER3, NPR3 | 0.02 |

| GO:0006916 | anti-apoptosis | CSF2, SQSTM1, TNFRSF10D, TNFAIP8, SKP2, NFKBIA, TNFAIP3, BIRC3 | < 0.01 |

| GO:0007398 | ectoderm development | TXNIP, NF2, FOXE1, TFAP2A, EMP1, KLF4 | < 0.01 |

| GO:0048729 | tissue morphogenesis | NF2, CASP8, FOXE1, TFAP2A, KLF4 | 0.02 |

Table 3.

Pathway enrichment of the 116 DEGs

| ID | Definition | Gene | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| hsa04120 | Ubiquitin mediated proteolysis | CUL3, SKP2, PML, NEDD4L, RCHY1, BIRC3 | < 0.01 |

| hsa04621 | NOD-like receptor signaling pathway | CASP8, NFKBIA, TNFAIP3, BIRC3 | 0.01 |

| hsa04210 | Apoptosis | TNFRSF10D, CASP8, NFKBIA, BIRC3 | 0.03 |

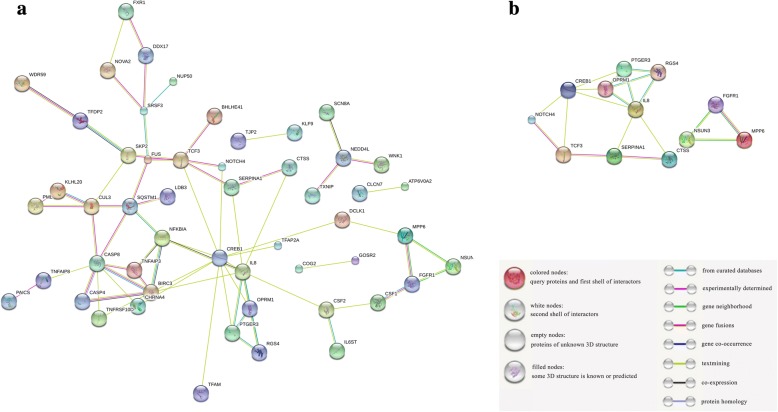

Protein and protein network

Next, the 116 DEGs were analyzed using the STRING database, and 71 protein-protein interactions (PPI) pairs were derived (Fig. 2a), which then underwent analysis using Cytoscape to construct PPI network. Using the plugin DCOME, we identified three significant modules consisting of the following 12 hub genes (Fig. 2b): CTSS, NOTCH4, IL8, CREB1, TCF3, SERPINA1, PTGER3, RGS4, OPRM1, MPP6, FGFR1, and NSUN3. We found using enrichment analysis that the main roles of these hub genes were in the inflammatory response.

Fig. 2.

The differential expressed protein–protein interaction network and network modules. a Protein and protein interaction (PPI) pairs of the 116 DEGs were constructed using the STRING database, and 71 PPI pairs were derived. b Modules of the PPI network were analyzed using Cytoscape plugin DCOME. Three significant modules containing 12 hub genes were identified. Module 1 comprise CTSS, NOTCH4, IL8, CREB1, TCF3, and SERPINA1, module 2 comprise PTGER3, RGS4, and OPRM1, and module 3 comprise MPP6, FGFR1, and NSUN3

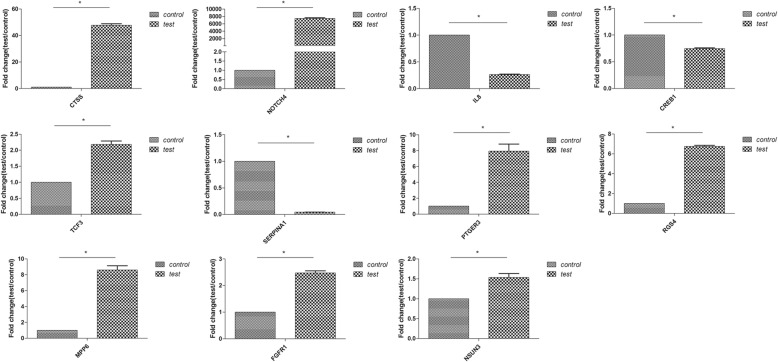

Verification of hub genes

To verify the 12 hub genes, we used qRT-PCR to identify the expression level of these differentially expressed mRNAs in human bronchial epithelial cells infected with Talaromyces marneffei (T.marneffei, Fig. 3). The results of qRT-PCR showed that all hub genes, except for OPRM1 were differentially expressed (P < 0.05, Table 4), and were consistent with the three microarray datasets. These suggest that the 12 hub genes may function as a group, and have a role in the pathogens infection to human bronchial epithelial cells.

Fig. 3.

Relative expression level of hub genes in BEAS-2B cells in response to Talaromyces marneffei. The expression level of mRNAs was performed using qRT-PCR. Results were shown as mean ± SD, * P < 0.05

Table 4.

Relative expression level of 12 hub genes in Talaromyces marneffei infected BEAS-2B cells

| Gene | Up/down regulation | Fold change (mean ± SD) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTSS | up | 47.734 ± 1.16 | P < 0.05 |

| NOTCH4 | up | 7435.900 ± 186.712 | P < 0.05 |

| IL8 | down | 0.263 ± 0.009 | P < 0.05 |

| CREB1 | down | 0.746 ± 0.013 | P < 0.05 |

| TCF3 | up | 2.180 ± 0.108 | P < 0.05 |

| SERPINA1 | down | 0.044 ± 0.002 | P < 0.05 |

| PTGER3 | up | 7.941 ± 0.888 | P < 0.05 |

| RGS4 | up | 6.743 ± 0.118 | P < 0.05 |

| MPP6 | up | 8.605 ± 0.532 | P < 0.05 |

| FGFR1 | up | 2.475 ± 0.080 | P < 0.05 |

| NSUN3 | up | 1.532 ± 0.102 | P < 0.05 |

| OPRM1 | – | – | P>0.05 |

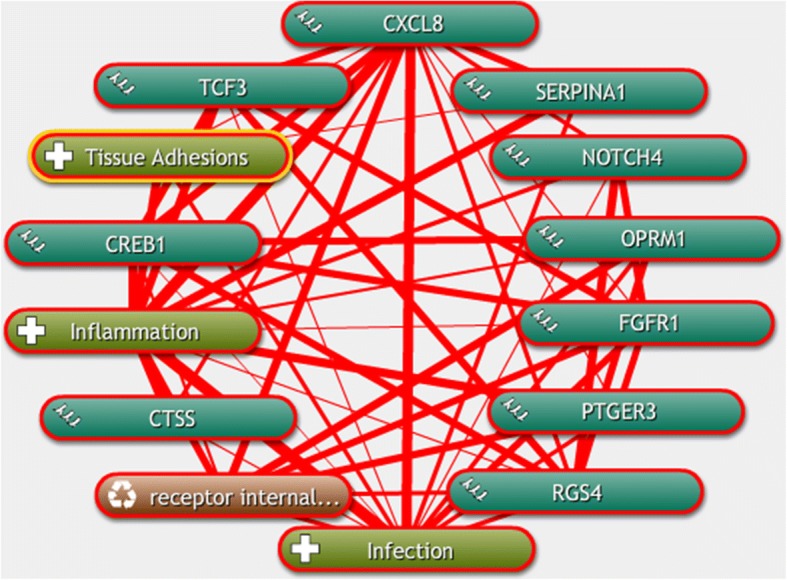

Text mining and prediction of miRNA

To demonstrate further the relationship between the hub genes and respiratory tract infection, text mining was performed using COREMINE. Co-occurrence analysis of the literature was conducted using “gene symbols”, “receptor internalization”, “tissue adhesion”, “inflammation”, and “infection” as search terms. We found that 10 genes (CTSS, NOTCH4, IL8, CREB1, TCF3, SERPINA1, PTGER3, RGS4, OPRM1, and FGFR1) were identified in the text-mining searches. Although all 10 of these genes were related to both inflammation and infection in the literature, we also found that two of these genes IL8 and SERPINA1 were associated with tissue adhesion, whereas six genes IL8, CREB1, RGS4, PTGER3, OPRM1, and FGFR1 were associated with and receptor internalization (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The linear relationship between the hub genes retrieved using COREMINE. Ten hub genes were associated with tissue adhesion, receptor internalization, inflammation and infection. The thicker the line, the closer the connection between the two ends

Searching the miRWalk, miRanda, miRDB, RNA22, and Targetscan databases, we predicted miRNAs for the 12 hub genes previously identified. Although eight miRNAs (hsa-miR-762, hsa-miR-93-5p, hsa-miR-20a-5p, hsa-miR-3192-5p, hsa-miR-1294, hsa-miR-1972, hsa-miR-106b-5p and hsa-miR-526b-3p) were predicted by all 5 databases, we found that only one gene (TCF3) has a miRNA-target interaction. In addition, we found that hsa-miR-762 was associated with pathogen infection [8]. There was no evidence in the literature regarding the remaining miRNAs and an association with infectious diseases.

Discussion

The GEO database includes high-throughput gene expression datasets and other functional genomics data [9]. The online tool, GEO2R is based on the R programming language and performs statistical analysis enabling users to access and analyze practically any GEO Series, regardless of data type [10]. This tool was used to analyze published microarray data in the GEO database. However, because the scope of microarray analysis in independent studies may have been limited, and that different experiments may identify different gene or mRNA targets, the robustness and reliability of these previous findings may be limited. To address this potential limitation in the present study, we used three independent microarray datasets of gene expression from airway epithelial cells responding to infection by respiratory pathogens, and collectively analyzed and evaluated all three datasets in our study. Therefore, our identification of genes that are significantly dysregulated in airway epithelial cells exposed to pathogens was identified using the collective data from three different microarray expression studies.

In the present study, we found 116 DEGs in our analysis of three independent microarray datasets. We used GO enrichment to understand better the underlying biological processes that are associated with these genes. GO is a major bioinformatics initiative to unify the characterization of gene and gene product attributes in all organisms [11]. For the present study, GO terms may identify the putative role that our set of genes may have in the process of the pathogen infection of airway epithelial cells. Our analysis of biological processes and signaling pathways demonstrated that these 116 genes were mainly involved in myeloid cell differentiation, cytokine stimulus, regulation of tyrosine phosphorylation of the STAT protein, regulation of the JAK-STAT cascade, and the NLR signaling pathway. These findings indicate that the functions of these genes are closely related to the immune response. For example, the JAK-STAT cascade is a major intracellular signaling response elicited by class I cytokine receptors, the activation of which results in direct and rapid changes in gene expression upon cytokine stimulation [12]. In addition, The NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome is a multiprotein complex that orchestrates innate immune responses to infection and cell stress through activation of caspase-1 (CASP1) and maturation of the inflammatory cytokines pro-interleukin-1β (pro-IL-1β) and pro-IL-18 [13].

To examine further the interrelationships between the DEGs, we constructed a PPI network and identified the following 12 hub genes: CTSS, NOTCH4, IL8, CREB1, TCF3, SERPINA1, PTGER3, RGS4, OPRM1, MPP6, FGFR1, and NSUN3. We found that these hub genes may function as a group and have an important role in viruses or bacteria infection. In order to investigate whether the group of hub genes is altered by particular pathogen, we further identified these hub genes by qRT-PCR in BEAS-2B cells infected by T.marneffei, a thermal dimorphic pathogenic fungus, which is able to cause fatal systemic infections in human. Our results showed that these hub genes involved in human bronchial epithelial cell in response to T.marneffei. So we posit that these genes may have clinical applications serve as biomarkers for early respiratory tract infection. In addition, we found using enrichment analysis that these hub genes were also associated with inflammation.

Text mining indicated that the majority of these hub genes were related to tissue adhesion, receptor internalization, inflammation, and infection. For example, human epithelial cells infected with Chlamydia secrete IL8, which is known to be activated by p42/44 MAPK cascade [14]. Aronoff et al. demonstrated that the prostaglandin E receptors 2 and 3 (PTGER2-PTGER3) axis has important roles in the prevention and treatment of infectious diseases [15]. In addition to the host defense response, adhesion, receptor internalization, and inflammatory responses are intrinsic to pathogen invasion. Of the 12 hub genes identified, we found that two genes were associated with tissue adhesion, six genes were associated with receptor internalization, and 10 genes were associated with inflammation. This finding demonstrates that these genes may have key roles in the process of pathogen infection in airway epithelial cells. Adhesion, receptor internalization and inflammatory response were intimately related to the invasion of pathogens and host defense against pathogens [6]. However, because there are no prior reports in the literature regarding the two hub genes MPP6 and NSUN3, and their potential role in airway epithelial cell infection, further studies to investigate their functions are warranted.

To provide additional targets for further research, we also preformed miRNA prediction of these hub genes. We found that a single gene (TCF3) has a miRNA-target interaction. Whereas among the eight candidate targets of microRNAs, hsa-miR-762 was previously reported to be associated with Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection [8], we did not find any prior investigations with the remaining seven in silico predicted miRNAs and infection. However, based on our findings, these miRNAs may warrant future study.

Conclusions

In summary, by integrating the data from 3 independent microarray studies, and though an extensive functional assessment including evaluation of signaling pathways, annotation of biological processes, determination of protein-protein interactions, text mining, and identification of miRNA-target interactions, we identified a robust set of DEGs associated with airway epithelial cell response to pathogen infection. This group of genes may be tested in the sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid samples as biomarkers for the diagnosis or the surveillance of early respiratory tract infections. In addition, we identified several genes and miRNAs as intriguing targets for further research. Understanding the pathogenesis will not only lead to improving prognosis and diagnosis, but also better therapeutic strategies and treatments to prevent respiratory tract infections.

Methods

Data collection and identification of DEGs

Three mRNA microarray expression profile datasets GSE3397 [16], GSE6802 [17] and GSE48466 [18] were retrieved from the GEO database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/, accession numbers: GSE3397, GSE6802, and GSE48466) [9]. DEGs were screened using GEO2R, which is an interface web tool available in GEO. The identification of DEGs between human airway epithelial cells exposed to respiratory pathogens and normal cells was statistically filtered using a P-value < 0.05.

Bioinformatics analysis

GO and KEGG Pathway enrichment analyses were performed using the online tool DAVID version 6.8 (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) [19]. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Protein and protein interaction networks were constructed using STRING version 10.0 (http://string-db.org/) [20]. The STRING database enables a critical assessment and integration of PPI, including physical as well as functional associations [20]. DEGs were mapped into the protein search, the organism was defined as Homo sapiens, and the genes were queried in the interaction networks. The Molecular Complex Detection (DCOME) in Cytoscape was used to analyze the modules of the PPI network. A score greater than three was identified as hub nodes and edges. Text mining for prediction of gene function was performed using COREMINE (http://www.coremine.com/medical/) [21]. To predict miRNA-target interactions in the 3′-UTR region of genes, we used the miRWalk, miRanda, miRDB, RNA22 and Targetscan databases (http://zmf.umm.uni-heidelberg.de/apps/zmf/mirwalk2/) [22].

T.marneffei strain and conidia preparation

T.marneffei strain was isolated from the sputum of a patient suffering from disseminated T. marneffei infection at the first affiliated hospital of Guangxi Medical University. T.marneffei was isolated as part of standard care of the patient, and was cultured on potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium (Beijing Luqiao Technology) at 25 °C for 7–10 days. Colonies were washed with sterile phosphate buffed saline (PBS), and then conidia were collected by centrifugation.

Cell line culture and fungal infection

The human bronchial epithelial cell line BEAS-2B (ATCC® CRL-9609™) was stocked at the Experimental Center of Guangxi Medical University. Cells were cultured in RPMI1640 medium mixed with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) at 37 °C. The test group was infected with conidia of T.marneffei for 4 hours.

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

Cells of both control and test groups were used to extract total RNA with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA quality and quantity were measured by Nucleic Acid Protein Detector. Total RNA was used for synthesis of cDNA with the First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (TaKaRa). The qRT-PCR were run using the following program: 1 cycle at 95 °C for 30 s, 40 cycles at 95 °C for 3 s, and an extension step at 60 °C for 30 s. The relative expression level of mRNAs was performed by using 2−ΔΔCT analysis method [23].The primers used are as follows (Table 5). GAPDH expression served as internal control.

Table 5.

Primers used for qRT-PCR

| Gene | Primer sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| CTSS-Forward | TCTCTCAGTGCCCAGAACCT |

| CTSS-Reverse | GTCTGAGTCGATGCCCTTGT |

| NOTCH4 - Forward | CTTGTCAGTCCCAACCCTGT |

| NOTCH4- Reverse | AGACACTCGTCCACGTCTCC |

| IL8- Forward | TAGCCAGGATCCACAAGTCC |

| IL8- Reverse | GCTTCCACATGTCCTCACAA |

| CREB1- Forward | GACGGAGGAGCTTGTACCAC |

| CREB1- Reverse | GCTGGGCTTGAACTGTCATT |

| TCF3 - Forward | TGCACAGCTCTCTGAAATGG |

| TCF3- Reverse | GGCAAAGGAGTGAAGGACAG |

| SERPINA1- Forward | TGCAGCCTGACTTCTTTGTG |

| SERPINA1- Reverse | AAGGACTCTCCTGGCCCTTA |

| PTGER3- Forward | GAGAGCAAGCGCAAGAAGTC |

| PTGER3- Reverse | CTGCTTGGACAGGTACACGA |

| RGS4 - Forward | ACAGGCTTAGCAGGAAGACG |

| RGS4- Reverse | AATTCGCAAGCAGGAAAGAA |

| OPRM1- Forward | ATCCCTCTTTCCTTGCCAAT |

| OPRM1- Reverse | GGAGTTCTCCGTCTGACAGC |

| MPP6- Forward | CAGCTGGTGGAAGGTCTGTT |

| MPP6- Reverse | TTTGTGAGTGGTCTGGTTGG |

| FGFR1- Forward | GAACAGGCATGCAAGTGAGA |

| FGFR1- Reverse | GCTGTAGCCCTGAGGACAAG |

| NSUN3- Forward | CTCTACATGCACGCTTTCCA |

| NSUN3- Reverse | GTGAAGTCGTGGGAGCAAGT |

| GAPDH- Forward | GCACCGTCAAGGCTGAGAAC |

| GAPDH- Reverse | TGGTGAAGACGCCAGTGGA |

Statistical analysis

Results are shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for three repeated independent experiments for each group. Statistical comparisons were conducted by using SPSS20.0 and significance was assessed by two-tailed Student’s t-test. Results with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Additional files

The GSE3397 mRNA expression profile dataset. 2033 DEGs between normal and infected airway epithelial cells were identified. (XLSX 158 kb)

The GSE6802 mRNA expression profile dataset. 1241 DEGs between normal and infected airway epithelial cells were identified. (XLSX 101 kb)

The GSE48466 mRNA expression profile dataset. 12950 DEGs between normal and infected airway epithelial cells were identified. (XLSX 964 kb)

Availability of data and materials

The raw data generated or analysed during this study are available online (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/, accession numbers: GSE3397, GSE6802, and GSE48466). The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DEGs

Differentially expressed genes

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- GO

Gene Ontology

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- PPI

Protein-protein interactions

- T.marneffei

Talaromyces marneffei

Authors’ contributions

ZH and YL conceived and designed the study. YL performed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. GL, JZ and XZ provided suggestions during manuscript preparation, and critically read and revised the manuscript. All authors of the manuscript have contributed,read and agreed to its content and are accountable for all aspects of the accuracy and integrity of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

T.marneffei was isolated as part of standard care of the patient and the subsequent isolation of the microorganism was undertaken according to standard laboratory processes. The patient in this study provided oral informed consent, and the rights and interests of the patient were fully considered and protected. Our study was approved by the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University Ethical Review Committee [Approval number: 2018(KY-E-013)]. The Medical Ethics Committee of First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University also approved the method of obtaining consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12866-018-1187-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Yinghua Li, Email: li_yinghua@163.com.

Guangnan Liu, Email: gnliu63@hotmail.com.

Jianquan Zhang, Email: jqzhang2002@sina.com.

Xiaoning Zhong, Email: xnzhong101@sina.com.

Zhiyi He, Phone: +86 18778017698, Email: zhiyi-he@163.com.

References

- 1.Pillay-van Wyk V, Msemburi W, Laubscher R, Dorrington RE, Groenewald P, Glass T, Nojilana B, Joubert JD, Matzopoulos R, Prinsloo M, et al. Mortality trends and differentials in South Africa from 1997 to 2012: second National Burden of disease study. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(9):e642–e653. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Disease GBD, Injury I, Prevalence C Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet (London, England) 2016;388(10053):1545–1602. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellinghausen C, Gulraiz F, Heinzmann AC, Dentener MA, Savelkoul PH, Wouters EF, Rohde GG, Stassen FR. Exposure to common respiratory bacteria alters the airway epithelial response to subsequent viral infection. Respir Res. 2016;17(1):68. doi: 10.1186/s12931-016-0382-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Villenave R, Broadbent L, Douglas I, Lyons JD, Coyle PV, Teng MN, Tripp RA, Heaney LG, Shields MD, Power UF. Induction and antagonism of antiviral responses in respiratory syncytial virus-infected pediatric airway epithelium. J Virol. 2015;89(24):12309–12318. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02119-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hippenstiel S, Opitz B, Schmeck B, Suttorp N. Lung epithelium as a sentinel and effector system in pneumonia--molecular mechanisms of pathogen recognition and signal transduction. Respir Res. 2006;7:97. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croft CA, Culibrk L, Moore MM, Tebbutt SJ. Interactions of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia with airway epithelial cells: a critical review. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:472. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ikeda M, Enomoto N, Hashimoto D, Fujisawa T, Inui N, Nakamura Y, Suda T, Nagata T. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae exploits the interaction between protein-E and vitronectin for the adherence and invasion to bronchial epithelial cells. BMC Microbiol. 2015;15:263. doi: 10.1186/s12866-015-0600-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mun J, Tam C, Chan G, Kim JH, Evans D, Fleiszig S. MicroRNA-762 is upregulated in human corneal epithelial cells in response to tear fluid and Pseudomonas aeruginosa antigens and negatively regulates the expression of host defense genes encoding RNase7 and ST2. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e57850. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clough E, Barrett T. The gene expression omnibus database. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, NJ) 2016;1418:93–110. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3578-9_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrett T, Wilhite SE, Ledoux P, Evangelista C, Kim IF, Tomashevsky M, Marshall KA, Phillippy KH, Sherman PM, Holko M, et al. NCBI GEO: archive for functional genomics data sets--update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue):D991–D995. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill DP, D'Eustachio P, Berardini TZ, Mungall CJ, Renedo N, Blake JA. Modeling biochemical pathways in the gene ontology. Database: the journal of biological databases and curation. 2016; 2016: article ID baw126. 10.1093/database/baw126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Li HS, Watowich SS. Innate immune regulation by STAT-mediated transcriptional mechanisms. Immunol Rev. 2014;261(1):84–101. doi: 10.1111/imr.12198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elliott EI, Sutterwala FS. Initiation and perpetuation of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and assembly. Immunol Rev. 2015;265(1):35–52. doi: 10.1111/imr.12286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Storrie S, Longbottom D, Barlow PG, Wheelhouse N. MAPK activation is essential for Waddlia chondrophila induced CXCL8 expression in human epithelial cells. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0152193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aronoff DM, Lewis C, Serezani CH, Eaton KA, Goel D, Phipps JC, Peters-Golden M, Mancuso P. E-prostanoid 3 receptor deletion improves pulmonary host defense and protects mice from death in severe Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950) 2009;183(4):2642–2649. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang YC, Li Z, Hyseni X, Schmitt M, Devlin RB, Karoly ED, Soukup JM. Identification of gene biomarkers for respiratory syncytial virus infection in a bronchial epithelial cell line. Genomic medicine. 2008;2(3–4):113–125. doi: 10.1007/s11568-009-9080-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayer AK, Muehmer M, Mages J, Gueinzius K, Hess C, Heeg K, Bals R, Lang R, Dalpke AH. Differential recognition of TLR-dependent microbial ligands in human bronchial epithelial cells. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950) 2007;178(5):3134–3142. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.3134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerlach RL, Camp JV, Chu YK, Jonsson CB. Early host responses of seasonal and pandemic influenza a viruses in primary well-differentiated human lung epithelial cells. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e78912. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang d W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(1):44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Wyder S, Forslund K, Heller D, Huerta-Cepas J, Simonovic M, Roth A, Santos A, Tsafou KP, et al. STRING v10: protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(D1):D447–D452. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Leeuw N, Dijkhuizen T, Hehir-Kwa JY, Carter NP, Feuk L, Firth HV, Kuhn RM, Ledbetter DH, Martin CL, van Ravenswaaij-Arts CM, et al. Diagnostic interpretation of array data using public databases and internet sources. Hum Mutat. 2012;33(6):930–940. doi: 10.1002/humu.22049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dweep H, Gretz N. miRWalk2.0: a comprehensive atlas of microRNA-target interactions. Nat Methods. 2015;12(8):697. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(6):1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The GSE3397 mRNA expression profile dataset. 2033 DEGs between normal and infected airway epithelial cells were identified. (XLSX 158 kb)

The GSE6802 mRNA expression profile dataset. 1241 DEGs between normal and infected airway epithelial cells were identified. (XLSX 101 kb)

The GSE48466 mRNA expression profile dataset. 12950 DEGs between normal and infected airway epithelial cells were identified. (XLSX 964 kb)