Abstract

The classroom microbiome is different from the home microbiome. Higher classroom microbial diversity is associated with increased asthma symptoms. In this pilot study, a school-level integrated pest management intervention changed the classroom microbiome.

Keywords: asthma, school, environment, microbiome, shotgun metagenomics sequencing

To the Editor

School endotoxin exposure contributes to asthma morbidity1. Recent shotgun metagenomics studies suggest that microbial identity, rather than microbial toxin levels alone, drives impacts of microbial exposure on chronic diseases2. In this pilot randomized controlled trial of school environmental interventions on indoor air quality and asthma symptoms, we sought to address three questions. First, is the school microbiome different from the home microbiome? Second, is the school microbial environment independently associated with asthma symptoms? Third, is the school microbiome modifiable?

We enrolled 25 children and performed a pilot randomized controlled trial of a combined integrated pest management (IPM) and high efficiency particulate air filter (HEPA) intervention in 21 classrooms from three schools. Asthma symptoms over a two-week period was assessed four times during the school year. Vacuumed dust was collected from homes once and schools three times for shotgun metagenomics sequencing (Figure S1). We inferred bacterial taxonomy at the species level, estimated microbial metabolic pathway abundances, used permutational analysis of variance (PERMANOVA)3 to test for differences in microbial community structure, and used MaAsLin4 to identify bacterial species associated with covariates. To test the hypothesis that school microbial diversity is associated with asthma symptoms, we used multivariate generalized additive mixed effects models (see detailed methods in Online Repository).

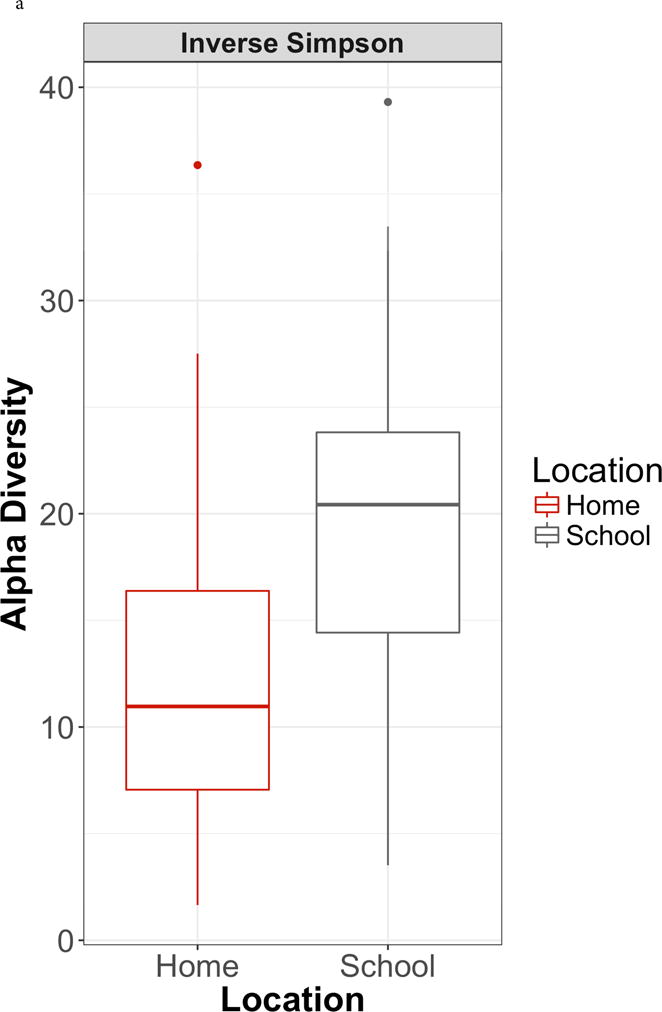

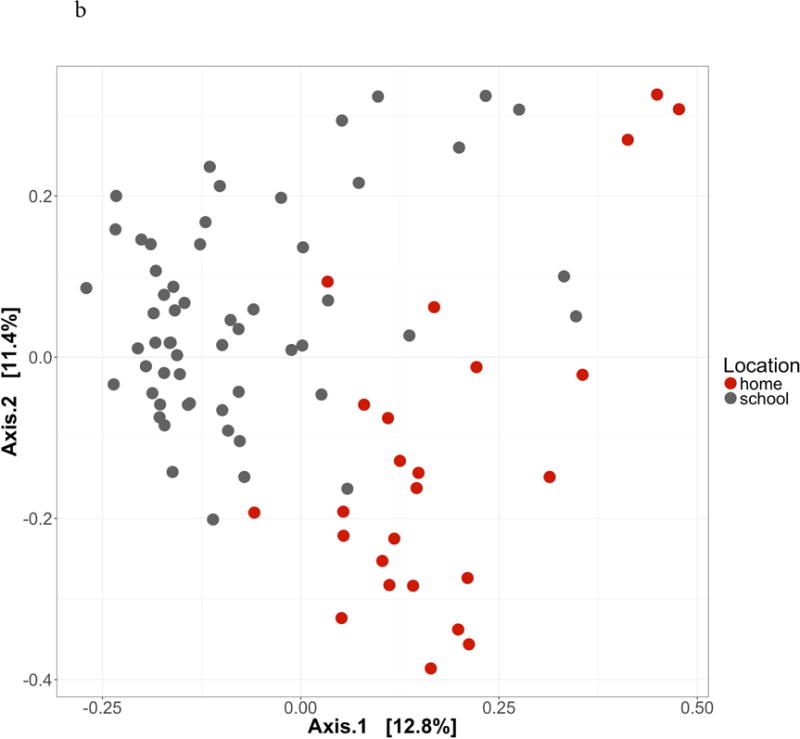

The study participants were on average 8.1 years old, from ethnic minority backgrounds, with 43.8% from households with annual incomes below the state poverty line (Table S1). Alpha diversity was significantly higher in classrooms compared to homes (Inverse Simpson β = 7.27 [1.21 – 13.34], p = 0.02) (Figure 1a). There were significant differences in microbial community structure between homes and classrooms (Figure 1b, PERMANOVA R2 = 0.087, p = 0.001). In adjusted analyses using MaAsLin, 86 distinct bacterial species were differentially abundant between classrooms compared to homes (Figure S2, Table S2), including a lower relative abundance of multiple species of Bacteroides and Staphylococcus. The only metabolic pathway that was differentially abundant between classrooms compared to homes was the chondroitin sulfate degradation I (bacterial) pathway (classroom vs. homes β = −0.49, p < 0.001, FDR-corrected q < 0.001). When specifically evaluating the lipid A biosynthesis pathway, different bacterial species contributed depending on location (Table S3), with Enterobacter cloacae, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella oxytoca contributing to this pathway in homes vs. Serratia marcescens in classrooms.

Figure 1. Classroom and home microbial community composition is different.

1a. Alpha diversity. Inverse Simpson index higher in schools compared to homes (β = β = 7.27 [1.21 – 13.34], p = 0.02). 1b. Beta diversity. Principal coordinates analysis of Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index demonstrates significant differences in microbial community composition between schools and homes (PERMANOVA R2 = 0.087, p = 0.001).

In a multivariate model adjusting for age, gender, ethnicity, and season, higher classroom microbial diversity was associated with increased asthma symptoms (OR = 1.07 [1.00 – 1.14], p < 0.05)); whereas home microbial diversity was not (1.00 [1.00 – 1.00], p = 0.91, Table 1). IPM was associated with microbial community structure in the classrooms (PERMANOVA R2 = 0.037, p = 0.004); HEPA-filtration was not (PERMANOVA R2 = 0.016, p = 0.446). In adjusted analyses using MaAsLin, 13 bacterial species were associated with the IPM intervention (Table S4).

Table 1. Association between classroom microbial diversity and asthma symptomsa.

Generalized additive mixed effects models were used to evaluate the association between both classroom and home microbial diversity and asthma symptoms, adjusting for gender, age, race, and season.

| Covariate | Odds Ratio [95% CI] | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Male vs. female | 0.92 [0.29 – 2.98] | 0.89 |

| Age in years | 1.33 [0.86 – 2.04] | 0.20 |

| Hispanic vs. black race | 1.58 [0.42 – 5.9] | 0.49 |

| Other vs. black race | 0.77 [0.15 – 4.02] | 0.75 |

| Classroom microbial diversityb | 1.07 [1.00 – 1.14] | 0.05c |

| Home microbial diversityb | 1.00 [1.00 – 1.00 ] | 0.91 |

| Seasond | 0.74 [0.38 – 1.47] | 0.39 |

Asthma symptoms defined as presence or absence of any of the following asthma symptoms in the 14 days prior to symptom survey administration: (1) daytime wheezing, chest tightness, or cough; or (2) days on which the child had to slow down or discontinue play activities due to wheezing, chest tightness, or cough; or (3) nights with wheezing, chest tightness, or cough leading to disturbed sleep.

Alpha diversity measured using the inverse Simpson index

p = 0.0469

Season modeled as penalized spline term on time

To our knowledge, this is the first study that compares the home vs. school microbial environment using shotgun metagenomics sequencing. Home and school indoor microbial communities are different, with higher classroom microbial diversity associated with increased asthma symptoms. An IPM intervention was associated with changes in the classroom microbiome. These findings suggest that it is important to account for microbial identity when defining healthy indoor environments, and that it may be possible for environmental interventions to alter the indoor microbial environment.

The home and school microbiome may differ due to construction, age of housing, presence of carpeting, or occupancy and composition of inhabitants. Most asthma studies assessing microbial diversity in the home have focused on asthma prevention rather than asthma symptom exacerbation. One recent cross-sectional home-based microbiome study found that higher home bacterial richness was associated with increased asthma severity in children5. While we observed that higher school microbial diversity was associated with increased asthma symptoms, we did not find the same association with home microbial diversity though home microbial diversity was assessed only once and exposure misclassification may have occurred. We assessed the classroom microbiome using vacuumed dust rather than air samples, which may explain why the HEPA air cleaner intervention was not associated with changes in measured classroom microbial community structure. This was a small pilot study, we were not adequately powered to address the health outcomes of this intervention, and our study cannot be taken to be representative of all schools in the Northeast United States. Our study did have several strengths. 1) It is based in a school setting, where children spend much of their day, and is therefore broadly relevant; future school-based interventions may be more feasible than targeting individual homes to create healthy indoor environments. 2) We used shotgun metagenomics sequencing rather than amplification and sequencing of marker genes such as the 16S rRNA gene, achieving higher taxonomic resolution, avoiding amplification bias6, and allowing for exploratory functional analysis of indoor microbial communities. 3) The study design is longitudinal, with randomized assignment of environmental interventions, allowing for causal interpretations. 4) We found no evidence of contamination in our negative controls.

There are several potential reasons why microbial identity is associated with asthma symptoms. A recent study showed that not all endotoxin is the same; endotoxin from Escherichia coli elicited a robust cytokine response in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells, while endotoxin from Bacteroides dorei inhibited the ability of Escherichia coli endotoxin to stimulate a cytokine response2. In our study, different bacterial species contributed to lipid A biosynthesis in homes vs. schools. Environmental microbes may produce metabolites that are then inhaled leading to asthma symptoms7. Alternatively, a recent occupational study of adults working with laboratory mice found that a proportion of their nasal and skin microbiome could be traced to their immediate work environment8; it is possible that environmental microbes exert their effect by changing the human microbiome.

While studies to date have focused on manipulating the human microbiome for health, the environmental microbiome may likewise be manipulated for health. Future research should focus on defining what constitutes a healthy indoor microbiome, and the mechanisms by which environmental microbes affect asthma.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge Kei Fujimura and Susan Lynch for their guidance on microbial DNA extraction from vacuumed dust samples.

Support: This work was supported by a Boston Children’s Hospital - Broad Institute Collaboration Grant, as well as in part by NIH grants R01 AI 073964, U01 AI 110397, K24 AI 106822, U01 AI 126614 (to W.P), K23 ES023700 (to P.S.L), P30 ES000002 (to D.D.) and 5T32AI007512 (to M.X.). This work was also supported by the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology Young Faculty Award. This work was conducted with support from Harvard Catalyst | The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award UL1 TR001102) and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers, or the National Institutes of Health. Coway, Inc. graciously donated air cleaners and provided support in building the sham cleaners.

The funding sources did not contribute to study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the report, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Lai PS, Sheehan WJ, Gaffin JM, Petty CR, Coull BA, Gold DR, et al. School Endotoxin Exposure and Asthma Morbidity in Inner-city Children. Chest. 2015;148:1251–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vatanen T, Kostic AD, d’Hennezel E, Siljander H, Franzosa EA, Yassour M, et al. Variation in Microbiome LPS Immunogenicity Contributes to Autoimmunity in Humans. Cell. 2016;165:842–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McArdle B, Anderson M. Fitting multivariate models to community data: a comment on distance-based redundancy analysis. Ecology. 2001;82:290–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morgan XC, Tickle TL, Sokol H, Gevers D, Devaney KL, Ward DV, et al. Dysfunction of the intestinal microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease and treatment. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R79. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-9-r79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dannemiller KC, Gent JF, Leaderer BP, Peccia J. Indoor microbial communities: Influence on asthma severity in atopic and nonatopic children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:76–83.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brooks JP, Edwards DJ, Harwich MD, Jr, Rivera MC, Fettweis JM, Serrano MG, et al. The truth about metagenomics: quantifying and counteracting bias in 16S rRNA studies. BMC Microbiol. 2015;15:66. doi: 10.1186/s12866-015-0351-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birzele LT, Depner M, Ege MJ, Engel M, Kublik S, Bernau C, et al. Environmental and mucosal microbiota and their role in childhood asthma. Allergy. 2017;72:109–19. doi: 10.1111/all.13002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lai PS, Allen JG, Hutchinson DS, Ajami NJ, Petrosino JF, Winters T, et al. Impact of environmental microbiota on human microbiota of workers in academic mouse research facilities: An observational study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0180969. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.