Abstract

INTRODUCTION

We compared risk of progression from subjective cognitive decline (SCD) to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in an academic memory clinic vs. a population-based study.

METHODS

Older adults presenting at a memory clinic were classified as SCD (n=113) or as non-complainers (NC; n =82). Participants from a population study were classified as SCD (n= 592) and NC (n=589) based on a memory complaint score. Annual follow-up occurred for three years.

RESULTS

The adjusted hazard ratio for SCD was 15.97 (95% CI 6.08 – 42.02, p<.001) in the memory clinic vs. 1.18 (95% CI 1.00 – 1.40, p=.047) in the population study, where reported “worry” about memory further increased SCD-associated risk for MCI.

DISCUSSION

SCD is more likely to progress to MCI in a memory clinic than the general population; participants’ characteristics vary across settings. Study setting should be considered when evaluating SCD as a risk state for MCI and dementia.

Keywords: memory complaints, cognitive decline, longitudinal design, selection factors

I. Introduction

There has been increased interest in recent years in older adults’ self-appraisal of memory and other cognitive abilities. ‘Subjective cognitive decline’ (SCD) refers to self-perceived worsening over time of cognitive functions. In 2014, an international working group, the Subjective Cognitive Decline Initiative (SCD-I), put forth a conceptual framework for research efforts [1]. In addition to establishing common terminology, definitions and proposed criteria, a goal was to identify potential features most strongly associated with presence of preclinical Alzheimer Disease (AD). Two proposed inclusion criteria for SCD are: 1) self-experienced persistent decline in cognitive capacity in comparison with a previously normal status, unrelated to an acute event, and 2) normal performance on standardized cognitive tests. Additional features potentially increasing the likelihood of preclinical AD include age of onset ≥60 years, reported worry or concern, and genetic or biomarkers for AD. Use of SCD as an enrichment strategy for preclinical AD in secondary prevention trials has been discussed [2].

A challenge to the SCD field is the fact that self-experienced decline in memory, even persistent, is a common or normative experience as we age [3, 4]. Etiologies of this subjective experience are highly heterogeneous [1, 5]. In populations at lower a priori risk for underlying AD pathology, SCD is less likely to represent a pre-mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and pre-dementia AD stage than in other populations. Selection factors operating in different research settings are an important reflection of the degree of underlying AD pathology. In epidemiologic terms, predictive value is a function of underlying prevalence. This has been demonstrated in studies of MCI: progression to dementia is lower in population settings (3% per year) compared to MCI ascertained in specialized memory clinic settings (13 % per year) [6]. Further, MCI which reverts to normal cognitive status is higher in population vs. clinic samples [7]. Clinical and sociodemographic factors, such as age of memory symptom onset, family history of dementia, APOE*4 status, education, and income level differ significantly among study settings and populations and are likely strongly associated with differences in outcomes [6, 8–10].

Because SCD theoretically resides closer to the normal/early pathologic boundary in cognitive aging than does MCI, the influence of study setting on SCD outcomes may be even more important than in studies of MCI outcomes. Rodriguez-Gomez et al., 2015 [11] described a conceptual model of study settings in SCD, arranged as a continuum of sampling methods from random-based population studies to non-randomly selected convenience samples. Clinical (i.e., help-seeking) samples constitute the most highly selected settings, with specialty clinics being more selected than general medical settings. Gomez-Rodriguez et al. called for SCD investigators to evaluate the impact of study setting and recruitment strategies via direct comparisons. We are unaware of studies to date directly comparing study settings on SCD outcomes. Thus, our present aim was to compare progression from SCD to MCI in a help-seeking, specialty clinic sample to the same outcome in a randomly recruited population-based cohort. We conducted a post-hoc comparison of two different studies in different settings in the same geographic community, with similar aims and similar methods. We predicted a higher progression risk associated with SCD (relative to no SCD) in the specialty clinic setting, compared to the same risk in a population-based study setting. Secondary aims were to investigate whether additional AD-like features of SCD [1], 1) reported worry or concern, and 2) presence of the APOE*4 allele, increased the predictive value of SCD for progression in the population study setting.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

2.1.1 Memory disorders clinic

N=195 consecutive participants enrolled in the University of Pittsburgh Alzheimer Disease Research Center (ADRC) were included. Inclusion criteria were 1) English language fluency; 2) > 7 years education; 3) adequate vision & hearing to complete neuropsychological (NP) testing. Exclusion criteria were 1) lifetime history of schizophrenia, manic-depressive disorder, or schizoaffective disorder; 2) recent history of electroconvulsive therapy; 3) current alcohol or drug abuse/dependence; 4) history of cancer (other than skin and in situ prostate cancer) within previous 5 years; 5) significant disease or unstable medical condition (i.e., chronic renal failure, chronic hepatic disease, severe pulmonary disease).

2.1.1.1 Subjective cognitive decline (SCD)

Participants in the ADRC further fulfilled these criteria: 1) Concern regarding memory or other cognitive abilities was a reason for seeking evaluation; 2) performance was normal on a comprehensive NP test battery (see below); 3) at least one annual follow-up visit was completed. SCD status corresponded to an ADRC consensus diagnosis of ‘subjective complaints with normal NP test performance.’ N=113 SCD-ADRC participants were selected for this analysis.

2.1.1.2 Non-complainers (NC)

Participants in the ADRC setting fulfilled all of the above criteria except for an absence of significant memory concerns at initial visit (i.e., contact was initiated for other reasons, such as volunteerism). NC status corresponded to an ADRC consensus diagnosis of ‘normal control.’ N=82 NC-ADRC participants were included.

2.1.2 Population study

N=1982 participants were randomly selected for the Monongahela-Youghiogheny Health Aging Team (MYHAT) study [12] from the voter registration lists for several small towns in Allegheny County, the same Southwestern Pennsylvania county as the University of Pittsburgh ADRC. Inclusion criteria were age 65+ years, currently living in the community in one of the targeted towns and not already residing in a long-term care facility. Exclusion criteria were being too ill to participate, severe hearing and vision impairment, and decisional incapacity. We further excluded individuals who had prevalent substantial cognitive impairment, defined as scores below 21 on the MMSE corrected for age and education [13, 14].

2.1.2.1 SCD

Participants from the MYHAT study were classified as SCD based on 1) scores above the median from a subjective memory complaint scale [15, 16] (see 2.2) at study baseline; 2) normal performance at baseline on a comprehensive NP test battery (see below); and 2) at least one annual follow-up visit completed. N=592 SCD-MYHAT participants were included.

2.1.2.2 NC

Participants from the MYHAT study fulfilled all of the above criteria, except that their scores on the subjective memory complaint scale were below the median. N=589 NC-MYHAT participants were included.

2.2 Subjective memory complaint scale

A self-report measure of cognitive complaints was completed at the MYHAT study baseline [15, 16]; a subset of 16 items relating to memory self-appraisal was used for this analysis. Example items include, “Do you feel you remember things less well than you did a year ago?” and “Are you same, better or worse than you used to be at… remembering things from a long time ago, things that happened or were said a few days ago, familiar/favorite recipes, etc.” Scores were the sum of items keyed toward worse functioning (possible range 0 – 16). The item “Are you worried about these/this problem(s) with remembering ?” was used in the secondary aim to investigate the effect of worry or concern as a putative AD-like feature [1] [17].

2.3 Neuropsychological evaluation

2.3.1 Memory disorders clinic

The PITT-ADRC diagnostic NP battery consisted of tests of a) memory (CERAD Word List Learning [18], WMS-R Logical Memory Story A [19], modified Rey Osterrieth [R-O] figure recall [20]); b) visuospatial construction (modified WAIS-R Block Design] [21], copy of the R-O figure); c) language: semantic and letter fluency, Boston Naming Test [22]); d) attention and executive functions: Trail Making Test [23], WAIS-R Digit Symbol and Digit Span forward and backward [24], Stroop color-word interference test [25], clock drawing, and abstract reasoning subtest from the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale). General mental status was assessed with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [14]. Criteria for normal performance were: 1) no more than 1 test score lower than expected within a cognitive domain and no more than 2 scores lower than expected across domains, with the threshold corresponding to −1.0 SD below age-adjusted control means.

2.3.2 Population study

The MYHAT NP test battery consisted of tests of a) memory: WMS-R Logical Memory [19], WMS-R Visual Reproduction; Fuld Object Memory Evaluation Test; b) visuospatial construction: WAIS-III-Block Design [24]; c) language: semantic and letter fluency; Boston Naming Test [22]; Indiana University Token Test [26]; d) attention and executive functions: Trail Making Test [23]; Digit Span forward [19]; clock drawing. General mental status was assessed with the MMSE. For each domain, we created a composite score (mean age- and education-adjusted Z score) and classified individuals as cognitively normal if all cognitive domain scores fell within 1.0 standard deviation (SD) of corresponding age- and education-adjusted means, based on previously published norms [27].

2.4 APOE genotyping

APOE genotyping was completed by the same laboratory for both the PITT-ADRC and MYHAT study participants using TaqMan SNP genotyping assays, as described previously [28].

2.5 MCI classification

2.5.1 Memory disorders clinic

The PITT-ADRC follows the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) and NIA-AA guidelines for MCI classification [29]. Cognitive adjudication was determined via a multi-disciplinary consensus conference [30] in which NP testing, medical and social history, daily functioning, reported cognitive symptoms, and neuroimaging findings were reviewed. NP criteria for MCI included scores on at least 2 individual tests within a cognitive domain, or 3 individual tests across cognitive domains, greater than 1.0 SD below age-corrected control means. Amnestic MCI (aMCI) classification required deficits on at least one memory test.

2.5.2 Population study

In the MYHAT study, participants were classified as MCI by neuropsychological criteria (NP-MCI) if one or more domain scores (averaged individual Z-scores within a domain) fell 1.0 SD below the mean, without meeting criteria for severe cognitive impairment (two or more domain scores at least 2.0 SD below the mean). Amnestic MCI and non-amnestic (naMCI) subtypes were based on the presence or absence of memory domain impairment.

2.6 Analysis

Baseline distributions of the demographics, APOE*4 carrier status, and education were compared by SCD status within each study setting and across settings using t-tests for continuous data and chi-square for categorical data.

Generalized linear models with Poisson distribution and log link were fit to estimate annual incidence rate of MCI. To study the effect of SCD on incident MCI in survival models, we first used log-log survival plot to assess the proportional hazards (PH) assumption for SCD in both study settings. The curves for SCD and NC did not significantly deviate from parallel, suggesting that the proportionality assumption was not violated. Thus, Cox proportional hazard regression models were applied to estimate the effect of SCD on incident MCI. The predictors of interest included SCD (vs. NC), APOE*4 carrier status, and SCD with and without worry. Univariable Cox models and covariates-adjusted Cox models were fit. In the analyses of effects of SCD/NC further categorized by APOE*4 carrier status, the proportional hazards assumption did not hold; we therefore fit parametric survival model with Weibull distribution.

Inverse probability weights (IPW) of being in the SCD or NC group given age, sex, and education were calculated. IPW-incorporated Kaplan-Meier curves adjusted for covariates were plotted to graphically compare the probability of maintaining normal cognition within each study.

3. Results

3.1 Comparisons within study samples

The ADRC sample (N=195) included 113 participants with SCD and 82 non-complainers (NC). The SCD group was significantly younger, and more likely to be male and white than the NC group.

The MYHAT sample (N=1181) included 592 participants with SCD and 589 NC participants. The SCD group was significantly older and had fewer years of education than the NC group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics by study setting and SCD classification

| Memory disorders clinic (ADRC) N=195 |

Population study (MYHAT) N=1181 |

ADRC vs. MYHAT p |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| SCD N=113 |

NC N=82 |

SCD vs. NC p |

All ADRC N=195 |

SCD N=592 |

NC N=589 |

SCD vs. NC p |

All MYHAT N=1181 |

||

| Age, mean (SD) Years | 65.99 (10.02) | 70.67 (9.21) | .001 | 67.96 (9.94) | 78.32 (7.32) | 76.22 (7.14) | <.001 | 77.27 (7.30) | <.001 |

| Sex, n of female (%) | 54 (47.79) | 62 (75.61) | <.001 | 116 (59.49) | 355 (59.97) | 368 (62.48) | .376 | 723 (61.22) | .646 |

| Years of education, mean (SD) | 15.79 (3.40) | 15.09 (2.73) | .118 | 15.49 (3.15) | 12.77 (2.44) | 13.10 (2.40) | .021 | 12.93 (2.42) | <.001 |

| Race, n of white (%) | 107 (94.69) | 64 (78.05) | <.001 | 171 (87.69) | 577 (97.47) | 578 (98.13) | .435 | 1155 (97.80) | <.001 |

| APOE*4a, n (%) | 43 (41.75) | 24 (30.38) | .115 | 67 (36.81) | 112 (20.74) | 97 (17.93) | .242 | 209 (19.33) | <.001 |

| Reported worry, n (%) | N/A | 84 (14.19) | N/A | ||||||

| Follow-up time in years, mean (SD) | 2.55 (2.10) | 5.73 (3.78) | <.001 | 3.89 (3.42) | 2.88 (2.29) | 3.30 (2.43) | .003 | 3.09 (2.95) | <.001 |

Note. ADRC = Alzheimer Disease Research Center; MYHAT = Monongahela-Youghiogheny Health Aging Team study; SCD = subjective cognitive decline; NC = non-complainers

The number of participants missing APOE*4 carrier status was 13 (7%) in the Memory Disorders Clinic and 100 (8%) in the Population study.

3.2 Comparisons between study samples

The mean age of the ADRC sample was significantly younger, the years of education was higher, the proportion with European ancestry was lower, and the proportion of APOE*4 carriers was higher compared to the MYHAT sample. (Table 1).

3.3 SCD predicting progression to MCI within study setting

As shown in Table 2, 37 (19%) of 195 ADRC participants and 586 (49.6%) of 1181 MYHAT participants progressed to MCI during the follow-up period. This corresponds to incidence rates of 5% per person-year (95% CI: 4% – 7%) for the ADRC and 16% per person-year (95% CI: 14% – 17%) for MYHAT. When further examined by SCD groups, the incidence rates in four groups (ADRC-SCD, ADRC-NC, MYHAT-SCD, MYHAT-NC) were 10% (95% CI: 7% – 15%), 2% (CI: 1% – 4%), 18% (CI: 16% – 20%), and 14% (12% – 16%), respectively. Among the MCI incident cases, 75.7% (28/37) were amnestic in the ADRC vs. 15.1% (86/568) in MYHAT (p<.001).

Table 2.

Annual incidence rates of MCI by study setting and SCD classification

| Memory disorders clinic (N=195) | Population study (N=1181) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual incidence rate (95 % CI) | 5% (4% – 7%) | 16% (14% – 17%) | ||

| Years of follow-up, mean (SD) | 3.89 (3.42) | 3.09 (2.95) | ||

| Number of participants progressed to MCI (N) | 37 | 568 | ||

| MCI subtype | ||||

| Amnestic MCI (N) | 28 | 86 | ||

| Non-amnestic MCI (N) | 9 | 482 | ||

|

| ||||

| SCD (N=113) | NC (N=82) | SCD (N=592) | NC (N=589) | |

|

|

||||

| Annual incidence rate (95 % CI) | 10% (7% – 15%) | 2% (1 – 4%) | 18% (16%–20%) | 14% (12% – 16%) |

| Years of follow-up, mean (SD) | 2.55 (2.10) | 5.73 (3.78) | 2.88 (2.29) | 3.30 (2.43) |

| Number of participants progressed to MCI (N) | 29 | 8 | 299 | 269 |

| MCI subtype | ||||

| Amnestic MCI (N) | 23 | 5 | 47 | 39 |

| Non-amnestic MCI (N) | 6 | 3 | 252 | 230 |

Note. SCD = subjective cognitive decline; NC = non-complainers; MCI = mild cognitive impairment

Stratified by age groups (<65, 65–74, 75–84,>=85 years old), the MCI incidence rates in the ADRC were 3% (95% CI: 2% – 6%), 4% (CI: 3% – 7%), 8% (CI: 4% – 15%), and 13% (4% – 41%), respectively. In MYHAT, MCI incidence rates by three age groups (65–74, 75–84, >=85 years old) were 11% (95% CI: 9% – 12%), 17% (CI: 15% – 19%), and 25% (CI: 21% – 30%), respectively.

In univariable Cox PH model, SCD participants were more likely to develop MCI than NC in both study samples. SCD remained significantly associated with MCI incidence after adjusting for age, sex, and education, with HRs of 15.97 (95% CI: 6.08 – 42.02) in ADRC and 1.18 (95% CI: 1.00 – 1.40) in MYHAT. In both samples, SCD participants had higher risk of progression than NC. In the ADRC sample, older individuals and those with more than high school education had significantly higher risk of progression. In MYHAT, only age was associated with MCI incidence. (Table 3).

Table 3.

Associations between SCD status and time to MCI progression, by study setting

| Memory disorders clinic | Population study | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1. Univariable Cox Model | ||||

|

| ||||

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

|

| ||||

| SCD | 7.38 (3.17 - 17.19) | <.001 | 1.26 (1.07 – 1.49) | 0.006 |

| Model 2. Covariates-adjusted Cox Model | ||||

|

| ||||

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

|

| ||||

| SCD | 15.97 (6.08 – 42.02) | <.001 | 1.18 (1.00 – 1.40) | 0.047 |

| Age | 1.09 (1.04 – 1.13) | <.001 | 1.05 (1.03 – 1.06) | <.001 |

| Sex a | 0.49 (0.23 – 1.03) | 0.061 | 1.01 (0.85 – 1.20) | 0.93 |

| Education b | 0.26 (0.10 – 0.70) | 0.008 | 1.04 (0.87 – 1.23) | 0.69 |

Note. SCD = subjective cognitive decline

Reference group: female

Reference group: more than high school education

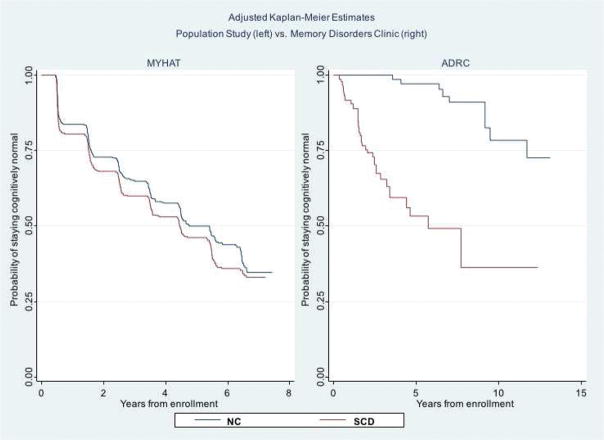

Weighted Kaplan-Meier curves (Figure 1) adjusted for age, gender, and education show a complete separation of the SCD and NC survival curves in the ADRC sample but not in the MYHAT sample, illustrating the relative effect sizes reported in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Adjusted Kaplan-Meier curves by subjective cognitive decline (SCD) vs. non-complainer (NC) status, in the population study (left) and in the memory disorders clinic (right). The y-axis shows the probability of remaining MCI-free and the x-axis shows the number of years of follow-up, which differs by study setting.

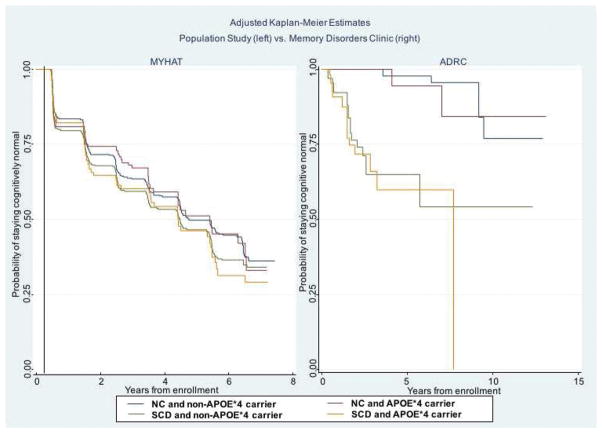

3.4 Role of APOE*4

SCD/NC were further categorized by APOE*4 carrier status into four groups: 1) NC/APOE*4 non-carriers, 2) NC/APOE*4 carriers, 3) SCD/APOE*4 non-carriers, and 4) SCD/APOE*4 carriers. Weighted Kaplan-Meier curves (Figure 2) illustrate that the differences in probability of remaining cognitively normal were mainly driven by SCD status, and not APOE*4 carrier status. The risk for progression was not significantly different among the four groups in MYHAT (Supplemental Table 1). In the ADRC sample, participants with SCD, regardless of their APOE*4 carrier status, had a higher risk of progression to MCI compared to the NC group without APOE*4 (SCD/APOE*4- non-carrier HR 16.04, 95% CI: 4.67 – 55.07, p < .001; SCD/APOE*4 carrier HR 20.72, 95% CI: 5.76 – 74.53, p < .001).

Figure 2.

Adjusted Kaplan-Meier curves by subjective cognitive decline (SCD) vs. non-complainer (NC) status and by APOE*4 allele carrier status, in the population study (left) and in the memory disorders clinic (right). The y-axis shows the probability of remaining MCI-free and the x-axis shows the number of years of follow-up, which differs by study setting.

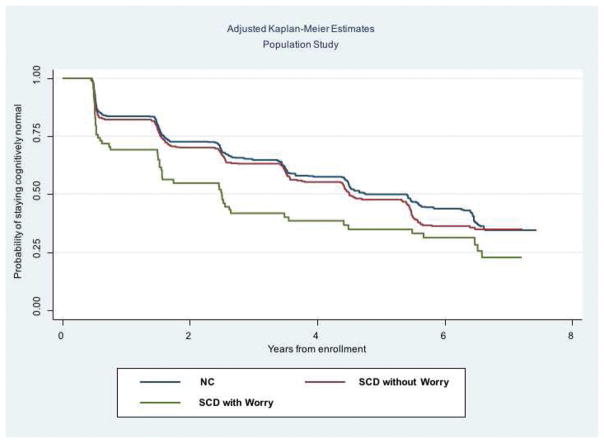

3.5 Role of ‘worry’ in the population study

Of the 592 MYHAT participants with SCD, 84 endorsed that they were “worried about problems with memory” and 508 responded they were not worried. SCD with “worry” had a higher risk of progression to MCI, compared with the NC reference group, after adjusting for age, gender, and education (Supplemental Table 2). Older age was also associated with higher risk of progression to MCI. Adjusted Kaplan-Meier curves are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Adjusted Kaplan-Meier curves by NC vs. SCD with worry vs. SCD without worry in the population study, only. The y-axis shows the probability of remaining MCI-free and the x-axis shows the number of years of follow-up.

4. Discussion

We investigated the role of study setting on a key clinical outcome of SCD, progression to MCI, over an average of three years follow-up. We found that SCD significantly predicted clinical progression both in a specialty memory disorders clinic and a population-based study. However the risk conferred by SCD (relative to non-complainers) was markedly larger in the memory clinic. The difference in SCD effect size between the two study settings was not accounted for by sample differences in APOE*4 carrier status.

What factors underlie these differences in the degree of SCD-associated risk for future cognitive decline? Among demographic factors to consider, the population cohort was older and less educated than the memory clinic sample. Both age and education were statistically accounted for in survival models within studies. Within the memory clinic sample, SCD participants were younger than NC; thus, age-associated risk for MCI cannot account for the larger SCD effect in the memory clinic setting. Between studies, however, the older age of the population cohort likely contributes to the higher overall progression rate to MCI [31]. Education was a significant predictor for MCI progression only in the memory clinic. Notably, its directional effect was opposite to what is typically reported: higher education was a risk factor for progression in the memory clinic setting, rather than being protective as is robustly observed across studies of cognitive aging [32, 33]. This may reflect a challenge inherent in the operationalization of SCD, which requires normal objectively measured cognition. Due to measurement limitations of cognitive assessment at the upper end of the ability spectrum, individuals with higher education/cognitive reserve and subtle, undetected cognitive deficits may be over-represented in the SCD category [34]. This is an important influence of a demographic factor that cannot be simply accounted for statistically. As well, this finding may be consistent with the cognitive reserve prediction of accelerated cognitive decline in higher reserve individuals subsequent to delayed onset of clinical symptoms [35, 36].

Among study design features, the memory disorder clinic was more highly selective in its inclusion/exclusion criteria, particularly regarding health history exclusions. Notably, major health conditions which could influence cognitive functioning (e.g., neurological and major psychiatric disorders) were excluded. In contrast, population study participants were more heterogeneous regarding potential etiologies of cognitive complaints and dysfunction. Regarding recruitment strategies, population study participants were randomly sampled from the voter registration list and approached by the study team, who systematically queried cognitive concerns. In contrast, memory clinic participants were self-referred because of spontaneously expressed cognitive concerns. A recent study of biomarker and clinical correlates of help-seeking vs. community recruited SCD reported higher degree of hippocampal atrophy and depressive symptoms associated with the former, suggesting that help-seeking is a meaningful facet of SCD with regard to underlying brain pathology [37].

The theoretical underlying prevalence of preclinical AD is smallest in population samples and largest in memory clinics, leading to lower and higher predictive values of risk factors, respectively [11]. In our ADRC sample, the proportion of the APOE*4 allele was higher overall, and the proportion of incident aMCI was higher (relative to naMCI), than in the MYHAT study. The main finding of differential SCD-associated risk for progression is thus consistent with the Rodriguez-Gomez conceptual model of sampling differences related to underlying risk for AD. It has been argued that SCD may be an efficient recruitment strategy for clinical trials targeting populations at early risk for AD [2]. Our findings demonstrate that SCD confers substantially different degrees of risk in a population setting vs. a specialty clinic, albeit variation in methods may also play a role. As noted by others [38, 39], SCD is a heterogeneous category. Our findings suggest SCD functions as a significant risk state in settings where the base-rate risk for AD is high, but not in settings where it is low. This heterogeneity likely applies across primary care settings, as well, where base-rates for AD may be similarly variable.

We also considered the role of AD-like features of SCD: 1) APOE*4 and 2) self-reported concern/worry. In both study settings, APOE*4 carrier status was not predictive of progression to MCI when modeled with SCD. In contrast, endorsed worry or concern, assessed in the population study only, further increased the risk for MCI progression. When the question “Are you worried about this/these problem(s) with remembering?” was considered, only SCD with worry was predictive of progression to MCI, and not SCD without worry. Jessen et al. [17, 40] reported the same pattern regarding SCD with and without concern in a large German primary-care population study, predicting progression to AD over four to six years. Thus, this facet of subjective cognition may add utility as a simple self-report item, e.g., on screening measures, in population-based or other less-selected settings. In effect, probing about worry or concern may serve to select individuals who are more similar to help-seekers in clinical or medical-research settings.

Limitations of the study are important to consider. Operationalization of SCD in the MYHAT study (i.e., via elicited complaints on a questionnaire) was different to that in the ADRC (i.e., via help-seeking behavior), although this divergence is inherent to our main research question. The two studies were from the same geographic community and had similar aims, but only partly similar methods. Importantly, the within-study comparisons of SCD vs. NC were methodologically uniform. Thus, the between-study comparisons at the level of effect size (i.e., HR) can be interpreted similarly to a qualitative review of independent studies with analogous methods. The comparison may also be similar to “constructive replication”, which evaluates generalizability of research findings across independent samples, measures, and designs [41, 42].

In sum, SCD confers a much lower risk for progression to mild cognitive impairment over three years in a population study setting, compared to a specialty memory clinic setting. Underlying base-rates of pre-clinical AD pathology likely underlies study differences. This has implications for SCD applications in unselected populations, such as public health screening initiatives. Future efforts should continue to further resolve the heterogeneity of SCD in aging so as to improve its clinical and research utility. Meanwhile, the role of study setting should be taken into account when evaluating and interpreting the literature on SCD.

Research in Context.

1. Systematic review

The authors reviewed the literature using traditional (e.g., PubMed) sources. A few publications address the importance of study setting in identifying SCD due to preclinical AD. These relevant citations have been appropriately cited.

2. Interpretation

Our findings support the model published by Rodriguez-Gomez et al, 2015, hypothesizing that the role of study setting has a significant effect on the likelihood that subjective cognitive decline is associated with preclinical AD. To our knowledge, it is one the first direct comparisons of clinical outcomes (i.e., progression to mild cognitive impairment) between two divergent study settings (i.e., specialized memory clinic vs. randomly recruited population study) addressing this hypothesis.

3. Future directions

The study proposes a framework for additional research. Examples include further understanding: (a) the role of worry/concern in predicting cognitive decline/disease progression, particularly in community or population-based settings; (b) the role of study setting in systematic reviews or meta-analyses of SCD outcomes in the research literature.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG023651; P50 AG005133; AG030653 and AG041718 to M.I.K.)

We would like to gratefully acknowledge the dedication, time and commitment of the participants and staff of the Monongahela-Youghiogheny Healthy Aging Team and the University of Pittsburgh Alzheimer Disease Research Center. Without their efforts, this research would not be possible.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None

The funding source had no role in study design, in collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, nor in the decision to submit the article for publication

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jessen F, Amariglio RE, van Boxtel M, Breteler M, Ceccaldi M, Chételat G, et al. A conceptual framework for research on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2014;10(6):844–852. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buckley RF, Villemagne VL, Masters CL, Ellis KA, Rowe CC, Johnson K, et al. A conceptualization of the utility of subjective cognitive decline in clinical trials of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. J Mol Neurosci. 2016;60(3):354–361. doi: 10.1007/s12031-016-0810-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montejo P, Montenegro M, Fernández MA, Maestú F. Subjective memory complaints in the elderly: Prevalence and influence of temporal orientation, depression and quality of life in a population-based study in the city of Madrid. Aging & Mental Health. 2011;15(1):85–96. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2010.501062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slavin MJ, Brodaty H, Kochan NA, Crawford JD, Trollor JN, Draper B, et al. Prevalence and Predictors of “Subjective Cognitive Complaints” in the Sydney Memory and Ageing Study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2010;18(8):701–710. doi: 10.1097/jgp.0b013e3181df49fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reid LM, Maclullich AMJ. Subjective memory complaints and cognitive impairment in older people. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;22(5–6):471–85. doi: 10.1159/000096295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farias ST, Mungas D, Reed BR, Harvey D, DeCarli C. Progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia in clinic-vs community-based cohorts. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(9):1151–1157. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malek-Ahmadi M. Reversion from mild cognitive impairment to normal cognition: A meta-analysis. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2016;30(4):324–330. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsuang D, Kukull W, Sheppard L, Barnhart RL, Peskind E, Edland SD, et al. Impact of sample selection on APOE∈ 4 allele frequency: A comparison of two Alzheimer’s disease samples. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44(6):704–707. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jonker C, Geerlings MI, Schmand B. Are memory complaints predictive for dementia? A review of clinical and population-based studies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15(11):983–91. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200011)15:11<983::aid-gps238>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crane PK, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, McCormick W, Bowen JD, Sonnen J, et al. Importance of home study visit capacity in dementia studies. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2016;12(4):419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodriguez-Gomez O, Abdelnour C, Jessen F, Valero S, Boada M. Influence of sampling and recruitment methods in studies of subjective cognitive decline. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2015;48(s1):S99–S107. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganguli M, Snitz B, Vander Bilt J, Chang CC, Ganguli M, Snitz B, et al. How much do depressive symptoms affect cognition at the population level? The Monongahela-Youghiogheny Healthy Aging Team (MYHAT) study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(11):1277–84. doi: 10.1002/gps.2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mungas D, Marshall SC, Weldon M, Haan M, Reed BR. Age and education correction of Mini-Mental State Examination for English and Spanish-speaking elderly. Neurology. 1996;46(3):700–6. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.3.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ganguli M, Dodge HH, Shen C, DeKosky ST. Mild cognitive impairment, amnestic type: an epidemiologic study. Neurology. 2004;63(1):115–21. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000132523.27540.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Snitz BE, Yu L, Crane PK, Chang C-CH, Hughes TF, Ganguli M. Subjective Cognitive Complaints of Older Adults at the Population Level: An Item Response Theory Analysis. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2012;26(4):344–351. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3182420bdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jessen F, Wiese B, Bachmann C, Eifflaender-Gorfer S, Haller F, Kolsch H, et al. Prediction of dementia by subjective memory impairment: effects of severity and temporal association with cognitive impairment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(4):414–22. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris JC, Heyman A, Mohs RC, Hughes JP, van Belle G, Fillenbaum G, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part I. Clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1989;39(9):1159–65. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.9.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wechsler D. Wechsler Memory Scale Revised. The Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Becker JT, Boller F, Saxton J, McGonigle-Gibson KL. Normal rates of forgetting of verbal and non-verbal material in Alzheimer’s disease. Cortex. 1987;23(1):59–72. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(87)80019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lopez OL, Becker JT, Jagust WJ, Fitzpatrick A, Carlson MC, DeKosky ST, et al. Neuropsychological characteristics of mild cognitive impairment subgroups. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(2):159–65. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.045567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaplan E, Goodglass H, Weintraub S. Boston Naming Test. 2. Philedelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reitan RM. Validity of the Trail-Making Tests as an indication of organic brain damage. Perceptal and Motor Skills. 1958;8:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. 3. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Golden CJ. A Manual for the Clinical and Experimental Use of the Stroop Color and Word Test. 1978 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Unverzagt FW, Morgan OS, Thesiger CH, Eldemire DA, Luseko J, Pokuri S, et al. Clinical utility of CERAD neuropsychological battery in elderly Jamaicans. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1999;5(03):255–259. doi: 10.1017/s1355617799003082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ganguli M, Snitz BE, Lee C-W, Vanderbilt J, Saxton JA, Chang C-CH. Age and education effects and norms on a cognitive test battery from a population-based cohort: the Monongahela–Youghiogheny Healthy Aging Team. Aging and Mental Health. 2010;14(1):100–107. doi: 10.1080/13607860903071014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheema AN, Bhatti A, Wang X, Ali J, Bamne MN, Demirci FY, et al. APOE gene polymorphism and risk of coronary stenosis in Pakistani population. BioMed research international. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/587465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2011;7(3):270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lopez O, Litvan I, Catt K, Stowe R, Klunk W, Kaufer D, et al. Accuracy of four clinical diagnostic criteria for the diagnosis of neurodegenerative dementias. Neurology. 1999;53(6):1292–1292. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.6.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Y, Denny KG, Harvey D, Farias ST, Mungas D, DeCarli C, et al. Progression from normal cognition to mild cognitive impairment in a diverse clinic-based and community-based elderly cohort. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2017;13(4):399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.07.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luck T, Luppa M, Briel S, Riedel-Heller SG. Incidence of mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2010;29(2):164–175. doi: 10.1159/000272424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharp ES, Gatz M. The relationship between education and dementia an updated systematic review. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2011;25(4):289. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318211c83c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Oijen M, de Jong FJ, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM. Subjective memory complaints, education, and risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2007;3(2):92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stern Y. Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. The Lancet Neurology. 2012;11(11):1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70191-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rajan KB, Wilson RS, Barnes LL, Aggarwal NT, Weuve J, Evans DA. A Cognitive Turning Point in Development of Clinical Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Biracial Population Study. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A. 2017;72(3):424–430. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glw246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perrotin A, La Joie R, de La Sayette V, Barré L, Mézenge F, Mutlu J, et al. Subjective cognitive decline in cognitively normal elders from the community or from a memory clinic: differential affective and imaging correlates. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2017;13(5):550–560. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mark RE, Sitskoorn MM. Are subjective cognitive complaints relevant in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease? A review and guidelines for healthcare professionals. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology. 2013;23(01):61–74. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Molinuevo JL, Rabin LA, Amariglio R, Buckley R, Dubois B, Ellis KA, et al. Implementation of subjective cognitive decline criteria in research studies. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2017;13(3):296–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jessen F, Wolfsgruber S, Wiese B, Bickel H, Mösch E, Kaduszkiewicz H, et al. AD dementia risk in late MCI, in early MCI, and in subjective memory impairment. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2014;10(1):76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hofer SM, Piccinin AM. Integrative data analysis through coordination of measurement and analysis protocol across independent longitudinal studies. Psychological methods. 2009;14(2):150. doi: 10.1037/a0015566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lykken DT. Statistical significance in psychological research. Psychol Bull. 1968;70(3):151–159. doi: 10.1037/h0026141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]