Abstract

Objective

To evaluate Aβ deposition patterns in different groups of cerebral β-amyloidosis: 1) non-demented with amyloid precursor protein (APP) overproduction [Down syndrome (DS)]; 2) non-demented with abnormal processing of APP [autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease (preADAD)]; presumed alteration in Aβ clearance with clinical symptoms [LOAD]; and 4) presumed alterations in Aβ clearance [preclinical AD (preAD)].

Methods

We performed whole brain, voxel-wise comparison of cerebral Aβ between 23 DS, 10 preADAD, 17 LOAD and 16 preAD subjects, using PiB-PET.

Results

We found both DS and preADAD shared a distinct pattern of increased bilateral striatal and thalamic Aβ deposition compared to LOAD and preAD.

Conclusion

Disorders associated with early-life alterations in APP production or processing are associated with a distinct pattern of early striatal fibrillary Aβ deposition prior to significant cognitive impairment. A better understanding of this unique pattern could identify important mechanisms of Aβ deposition and possibly important targets for early intervention.

Keywords: Down syndrome, Autosomal Dominant Alzheimer Dementia, Pittsburgh Compound B, Striatum, Diffuse Plaque, aβ42

Although the exact cause for the deposition of cerebral amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques remains uncertain, two main mechanisms are currently proposed: altered processing or overproduction of APP - as in autosomal dominant AD (ADAD) or Down syndrome (DS) - and impaired clearance - as in the case of later-life Aβ deposition seen in preclinical AD (preAD), Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) and late-onset AD (LOAD). It is probable that similar mechanisms contribute to both early- and late-onset forms of AD. However, it is clear that genetic disorders associated with the overproduction or altered enzymatic processing of amyloid precursor protein (APP) are associated with a very high risk of AD two to three decades earlier than that typical for LOAD.

The pathological features are similar for all forms of AD, but those with ADAD and DS have been shown to have an increase in the Aβ42/40 ratio compared to LOAD(Gomez-Isla et al., 1999; Lemere et al., 1996a; Lemere et al., 1996b). Additionally, amyloid-β (Aβ) PET studies in ADAD have identified a distinct pattern of early striatal deposition not commonly seen in LOAD, which was confirmed in a recent autopsy study (Shinohara et al., 2014). If this is related to an increased production of APP, it might be expected that a similar pattern would be identified in DS(Handen et al., 2012).

Therefore, we evaluated the early PiB PET Aβ deposition patterns in four different groups of subjects with evidence of cerebral β-amyloidosis: 1) non-demented with APP overproduction [DS]; 2) non-demented with abnormal processing of APP [preADAD]; 3) presumed alterations in Aβ clearance [preAD]; 4) presumed alteration in Aβ clearance with clinical symptoms [LOAD]. It was hypothesized that the pre-AD pattern of amyloid deposition in individuals with DS would be similar to that of those with preADAD.

Methods

Design and Participants

Following approval from the University of Pittsburgh and the University of Wisconsin- Madison Institutional Review Boards, all subjects were recruited through three ongoing studies of ADAD, DS (Pittsburgh and Wisconsin) and normal aging that included in vivo PiB PET and cognitive/functional performance (Pittsburgh) with a modified Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE). Further details of subject recruitment, cognitive and functional evaluation and determination of clinical diagnosis are provided in previous publications (Lao et al., 2016, {McDade, 2014 #16264; Nebes et al., 2013). Ten pre-ADAD subjects ≥18 years of age were included in the current study representing predominantly presenilin-1 (PS-1) mutation carriers as well as amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene mutations. The DS subjects (n=23) were ≥ 30 years of age. The preAD subjects (n=16) and the LOAD subjects (n=17) were ≥65 years of age and were matched to each other for both age and sex. ADAD gene mutations were confirmed through an approved commercial testing facility (Athena Diagnostics®, Worcester, MA) and chromosome 21 triplication was confirmed in all DS participants. All subjects underwent detailed cognitive and functional evaluations as well as MRI and PiB-PET imaging. For the purposes of this study only those subjects determined to be non-demented, based on a standard neuropsychological test battery, designed to assess those areas of cognition known to be impaired in LOAD and also to be sensitive to Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) (Petersen, 2004) were included in the preADAD and preAD groups. All DS participants had a mental age ≥ 30 months (based upon the Stanford-Binet 5th ed. (Roid, 2003)) and score in the asymptomatic range (< 3 CCS score) on the Dementia Scale for Down Syndrome (DSDS)(Gedye, 1995). The DSDS is an informant completed 60-item questionnaire focused on symptoms of dementia in DS. It has been found to have good sensitivity and specificity (Gedye, 1995). None of the adults with DS were taking memory enhancement or AD medications or had a medical or psychiatric condition that would impair cognitive functioning. Preclinical dementia stage in DS, was established by caregiver report and the use of a standardized interview for dementia in DS. Only subjects considered to be regionally PiB-positive [PiB(+)] based on methods described previously were included in this study(Cohen et al., 2013).

Imaging

MR imaging was performed with GE Medical Systems (Wisconsin) and Siemens Magnetom Trio (Pittsburgh). A volumetric MRI employing the Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative (ADNI) sequence(Jack et al., 2008) was performed at the time of the PiB-PET scan for the purposes of co-registration, region-of-interest placement and atrophy-correction. PET imaging was performed on a Siemens/CTI ECAT HR+ PET Scanner with a Neuro-insert (CTI PET Systems, Knoxville, TN, USA) in 3D mode. The [C-11]PiB was injected intravenously (12–15 mCi, over 20 s, specific activity ~1–2 Ci/μmol) and PET scanning was performed from 40–70 minutes post-injection (six five minute frames). The baseline full resolution MR was resliced along the AC-PC line and down-sampled to PET voxel space. After addressing any motion, the PiB PET data was summed to form a static image and co-registered to the down-sampled MR image. The PiB-PET data were averaged over 50–70 minute post-injection, and analysis utilized a standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) with cerebellar gray matter as reference (Lopresti et al., 2005). Global PiB was computed as the average SUVR of the following regions: anterior cingulate, striatum, pre-frontal cortex, lateral temporal cortex, parietal cortex, and precuneus cortex (Lopresti et al., 2005; McNamee et al., 2009; Rosario et al., 2011)Here after we refer to these six ROIs as the AD regions as they were derived from areas typically demonstrating high Aβ burden. PiB positivity was defined regionally based on an SUVR value above the cutoff in any one (or more) of these six regions.

For each subject the structural MRI was visually inspected for any artifacts or abnormalities. The structural MRI was segmented and normalized to the Montreal Neurologic Institute (MNI) space with the unified-segment procedure in SPM8(Ashburner and Friston, 2005). For voxel-based analyses, the averaged 50–70 minute PiB-PET images were then co-registered to the segmented-normalized MRI and visualized for appropriate registration.

Statistical Analysis and Parametric Imaging Methods

Appropriate descriptive and inferential statistics were used to compare groups including Student t-tests and chi-squared tests. For the between-group comparison we performed separate voxel-level t-tests across the entire brain with a global mean scaling to explore the effect of group status on PiB retention using SPM8. The statistical threshold was a False Discovery Rate of p<0.05. The SUVR values from the AD region ROIs were compared across all groups using an ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc analysis for the between group analysis and by a linear regression for each ROI by the global average of the 5 remaining ROIs, with the results centered so that the intercept should represent the mean of the preADAD group, including a correction for age. Based on our previous work suggesting a unique pattern of high striatal PiB binding in DS and ADAD, we chose to center the regression analysis on the ADAD group. This allowed for the simultaneous comparison of our other groups of interest (PiB + cognitively normal elderly and ADAD) to a group with early, elevated striatal PiB. We include the direct group by group comparisons for each ROI in the supplemental table.

Results

As expected, the groups differed significantly by age. In addition, the AD group had significantly lower MMSE, and both older groups had significantly higher proportions of APOe ε4 allele carriers (Table 1) and no significant differences in gender.

Table 1.

| Demographic, Regional & Global PiB-PET SUVR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Down Syndrome n=23 |

preADAD n=10 |

Elderly Control n=16 |

Late Onset AD n=17 |

|

| Age | 44.8 +/− 3.8†§϶ | 36.30 +/− 5.1¥# | 75.6 +/− 5.4 | 75.0 +/− 5.7 |

| Gender (%Male) | 57.9% | 30% | 43.7% | 47.1% |

| MMSE | NA | 27.8 +/− 2.2 | 28.3 +/− 1.9 | 22.5 +/− 4.4#* |

| APOe ε4 allele carrier | 9.10%§϶ | 16.7%¥# | 42.9%* | 70.6% |

| SUV/SUVR (Mean/SD) | ||||

| Cerebellar gray (SUV) | .67 +/− .16 | .68 +/−. 13 | .71 +/−.14 | .68 +/−.16 |

| Ant. Cingulate | 1.85 +/− .42 | 2.24 +/− .69 | 2.0 +/− .43* | 2.28+/− .38 |

| Striatum | 2.14 +/− .47§ | 2.42 +/− .56¥ | 1.69 +/− .36 | 2.02 +/− .38 |

| Frontal Cortex | 1.8 +/− .39† | 2.19 +/− .59 | 1.96 +/− .37* | 2.20+/− .32 |

| Lateral Temporal | 1.63 +/− .30 | 1.63 +/− .55 | 1.74 +/− .28* | 2.02+/− .32 |

| Parietal Cortex | 1.61 +/− .34§ | 1.78 +/− .51 | 1.90 +/− .31 | 2.04+/− .33 |

| Precuneus | 1.79 +/− .39 | 2.13 +/− .53 | 2.07 +/− .41 | 2.26+/− .32 |

| Global | 1.81 +/− .36 | 2.07 +/− .54 | 1.89 +/− .34* | 2.16+/− .31 |

Down Syndrome compared to ADAD;

Down Syndrome compared to Elderly Control;

ADAD compared to Elderly Control;

Down Syndrome compared to LOAD;

ADAD compared to LOAD;

Elderly Control compared to ADAD.

SUVR values represent bilateral average 50–70 min. values

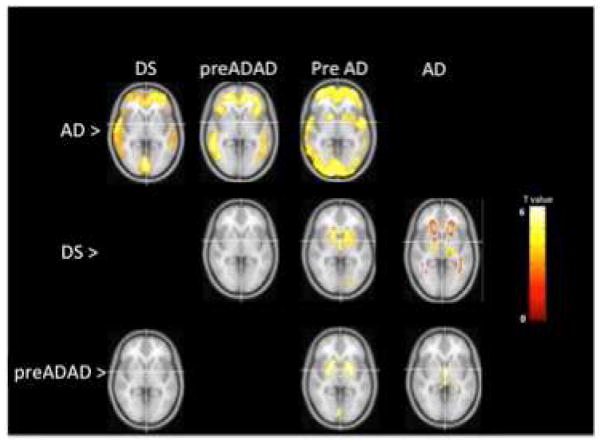

Voxelwise PiB PET Comparisons (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Voxelwise Comparison of Amyloid Patterns between ADAD, DS and LOAD. p-values FDR-corrected (p<0.05). Color bar represents t-values.

LOAD vs. DS

The LOAD group demonstrated significantly increased PiB retention compared to the DS group in regions including anterior cingulate, frontal cortex, temporal cortex and precuneus (Fig 1, LOAD>DS). There was a slight increase in PiB in the white matter observed in DS when compared to the LOAD group (Fig 1, DS>LOAD).

LOAD vs. preADAD

The LOAD group demonstrated significantly increased PiB retention compared to the preADAD group in regions including anterior cingulate, frontal cortex and temporal cortex (Fig 1, LOAD> preADAD). No areas of increased PiB retention in the ADAD group compared to the LOAD group exceeded the statistical threshold (Fig 1, preADAD>LOAD).

LOAD vs. PreAD

The LOAD group demonstrated significantly increased PiB retention compared to the PreAD group in regions including anterior cingulate, striatum, frontal cortex, parietal cortex and temporal cortex (Fig 1, LOAD>PreAD). No areas of increased PiB retention in the PreAD group compared to the LOAD group exceeded the statistical threshold.

DS vs preADAD

No areas of significant increase in DS were observed when compared to the preADAD group or vice versa (Fig 1, DS>preADAD; preADAD>DS).

DS vs preAD

The DS group demonstrated increased PiB retention in the bilateral striatum, including the caudate and putamen, (Fig 1, DS > PreAD). There were no areas of increased PiB retention in the preAD group compared to the DS group that exceeded the statistical threshold.

preADAD vs preAD

The preADAD mutation carriers demonstrated increased PiB retention compared to the preAD group in the bilateral putamen and, less so, in the caudate (Fig 1 preADAD>PreAD). We found no areas of increased PiB retention in the preAD group compared to the preADAD group that exceeded the statistical threshold.

Region-of-interest PiB PET Comparisons

ANOVA comparisons

Pathological studies have identified increased Aβ deposition in the cerebellum in DS and preADAD (Lemere et al., 1996b; Mann et al., 1990). Therefore, we compared the SUV for our cerebellar ROI for all groups and found no differences for the cerebellar gray matter between groups (supplementary table). When we compared the mean ROI SUVRs for our 6 regions, we observed significantly higher PiB retention in the LOAD group compared to the PreAD group in the anterior cingulate, frontal and lateral temporal cortices, as well as the global cortical region. There was also significantly higher PiB retention in DS group in the striatum when compared to both the LOAD and PreAD groups, as well as significantly higher PiB retention in the preADAD group when compared to the PreAD group and a trend for higher PiB retention when compared to the LOAD group (supplementary table).

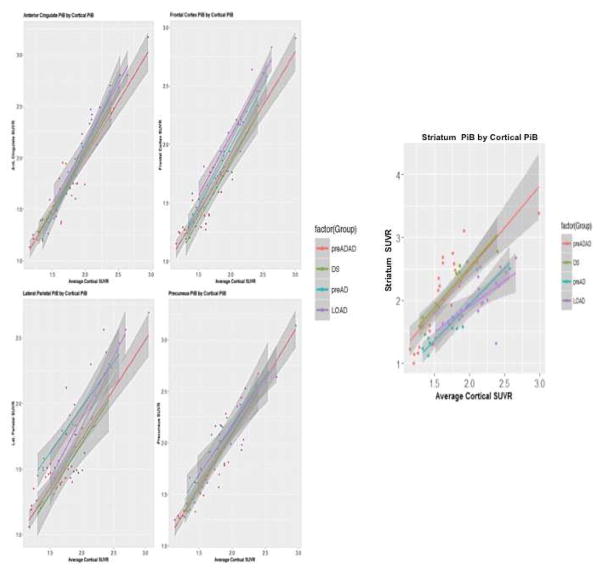

Linear Regressions

When we performed a linear regression using the preADAD group as the reference group for each mean ROI SUVR for the 6 regions examined compared to the average of the 5 remaining regions. These analyses revealed significant group effects for each of the 6 regions, driven primarily by significant differences between the PreAD and LOAD groups with the preADAD group. There were no ROIs where the ADAD and DS groups differed (Table 2, Figure 2).

Table 2.

LINEAR REGRESSION (preADAD as reference group, age corrected)

| STR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Std. Error | t value | Pr(>|t|) | |

| (Intercept) | 1.542343 | 0.221257 | 6.971 | 1.95e-09 *** |

| DS | −0.035458 | 0.110356 | −0.321 | 0.74901 |

| PreAD | −1.105388 | 0.218289 | −5.064 | 3.62e-06 *** |

| AD | −1.145749 | 0.207262 | −5.528 | 6.16e-07 *** |

| ACG | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Std. Error | t value | Pr(>|t|) | |

| (Intercept) | 1.989063 | 0.099176 | 20.056 | < 2e-16 *** |

| DS | 0.047694 | 0.110356 | 0.964 | 0.33853 |

| PreAD | 0.188148 | 0.097845 | 1.923 | 0.05887 |

| AD | 0.265385 | 0.092902 | 2.857 | 0.00574 ** |

| FRC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Std. Error | t value | Pr(>|t|) | |

| (Intercept) | 1.848816 | 0.082027 | 22.539 | < 2e-16 *** |

| DS | −0.038924 | 0.040903 | −0.952 | 0.344824 |

| PreAD | 0.203636 | 0.081081 | 2.512 | 0.014515 * |

| AD | 0.311143 | 0.076795 | 4.052 | 0.000138 *** |

| LTC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Std. Error | t value | Pr(>|t|) | |

| (Intercept) | 1.743397 | 0.102991 | 16.928 | < 2e-16 *** |

| DS | 0.034086 | 0.051373 | 0.663 | 0.50936 |

| PreAD | 0.286520 | 0.101902 | 2.812 | 0.00651 ** |

| AD | 0.311143 | 0.096411 | 3.445 | 0.00101 ** |

| PAR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Std. Error | t value | Pr(>|t|) | |

| (Intercept) | 1.744114 | 0.104844 | 16.635 | < 2e-16 *** |

| DS | −0.025477 | 0.052317 | −0.487 | 0.627915 |

| PreAD | 0.382280 | 0.103939 | 3.678 | 0.000479 *** |

| AD | 0.298741 | 0.098219 | 3.042 | 0.003392 ** |

| PRC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Std. Error | t value | Pr(>|t|) | |

| (Intercept) | 1.935380 | 0.111345 | 17.382 | < 2e-16 *** |

| DS | 0.007474 | 0.055584 | 0.134 | 0.8935 |

| PreAD | 0.185064 | 0.110133 | 1.680 | 0.0977 |

| AD | 0.137964 | 0.104368 | 1.322 | 0.1908 |

0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05

Figure 2.

Linear regression plots for each ROI vs. the average cortical ROI.

Discussion

Consistent with our hypothesis using PiB-PET, we found a distinct pattern of predominant striatal Aβ deposition that distinguished the Aβ deposition seen in late-onset preAD and AD from that of two types of early-onset Aβ deposition in non-demented DS and preADAD. This work extends the findings of early striatal Aβ deposition in ADAD (Klunk et al., 2007; Villemagne et al., 2009) to DS, further highlighting a unique characteristic of Aβ deposition that appears to be related to a life-long alteration of the dynamics of APP production and/or processing (Handen et al., 2012; Hartley et al., 2014) at least as it relates to the ADAD mutations represented in this population.

The mechanism behind this remains uncertain. Pathological studies have identified an increase in the level of Aβ-42 to Aβ-40 in both ADAD and DS compared to late onset AD (LOAD) with an additional finding of increased diffuse sub-cortical plaques in both young-onset forms of AD (Fukuoka et al., 1990; Gomez-Isla et al., 1999; Kida et al., 1995; Lemere et al., 1996a; Lemere et al., 1996b; Shinohara et al., 2014). How this might relate to the alterations in APP processing or increased APP levels is unclear. Early pathological studies found that the Aβ-42 forms of plaques were the first to develop in DS and in specific types of PS-1 mutation carriers, even as early as the 2nd decade (Lemere et al., 1996a; Lemere et al., 1996b). Other work confirmed that the N-terminal truncated Aβ-42 fragments are among the earliest form of Aβ plaques in DS (Liu et al., 2006) and may be related to elevated β-site amyloid precursor protein (APP)-cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1). Because these products of APP cleavage appear more resistant to degradation, they may work as early seeds of eventual plaque formation. However, another group demonstrated that ADAD was characterized by an increase in APP β-C-terminal fragment (β-CTF) levels with no changes in BACE protein (Pera et al., 2013).

In vivo studies of ADAD PS-1 carriers has confirmed an increase in the Aβ-42: 40 ratio in the CSF(Potter et al., 2013). Likewise, a recent biochemical-pathological study confirmed a higher level of sub-cortical Aβ-42 in ADAD compared to LOAD and preAD. In that work, Aβ-42 in ADAD was associated with plasma membrane markers such as APP and APP β-CTF (Shinohara et al., 2014) compared to LOAD. Whereas, compared to ADAD, LOAD was associated with higher levels of Aβ-42 plaques in cortical areas and these were more related with markers of synaptic function. The authors speculated that the anatomical distinctions of Aβ-42 levels might be due to a different processes contributing to plaque development in each disorder. In LOAD Aβ-42 levels might relate to an increased dependence of APP processing on synaptic activity thereby increasing the cortical deposition. In ADAD, Aβ-42 levels might relate to alterations in APP turnover/metabolism that result in persistent, early increases in APP products that eventually overwhelm mechanisms for Aβ removal. Further, in DS significant decreases in striatal volume have been observed in those with AD (Beacher et al., 2009), it is possible that the differences observed between the DS and LOAD groups in white matter, while small might be related to these differing atrophy patterns.

Interestingly, studies employing the Aβ-PET tracer [F-18]florbetapir have not identified the increased striatal retention in ADAD and DS (Fleisher et al., 2012; Sabbagh et al., 2011) seen with [C-11]PiB(Benzinger et al., 2013; Klunk et al., 2007; Villemagne et al., 2009). However, another single –case using Florbetaben in an ADAD patient has also identified a striking ‘striatal’ pattern of binding (Um et al., 2017). Different transmembrane domains of ADAD mutations (particularly PSEN1) could impact the tracer binding. In the case of DS, we are unaware of any other studies using Florbetapir that demonstrate the disproportionately robust striatum:cortical tracer retention that is seen with PiB-PET. This would suggest that there is an overall tracer by “cause” (ADAD or DS vs LOAD) binding pattern with contributions from both. In fact, Matveev et al., suggests that a distinct sub-fraction of Aβ is responsible for PiB binding, and in the case of DS and ADAD this sub-fraction may have a relatively higher volume in these sub-cortical regions (Matveev et al., 2014). These data suggest that at minimum the differences in tracers are likely an important contribution. However, these differences are not well understood and likely relate to differences in mutation carriers as well.

It is important to consider the reference tissue used in calculating SUVRs, particularly in ADAD and DS where there is evidence of increased Aβ plaque deposition in the cerebellum compared to late onset AD. However, we would expect to see lower SUVR values for all regions in the two young-onset groups if this were the case. Furthermore, the reference region cancels out when comparing ratios of regions. Therefore, we do not think that the results are due to differences in the cerebellar gray matter reference tissue used for this study. A recent study using [F-18]florbetapir with pathological confirmation found that a cerebellar reference remained accurate even with the presence of cerebellar Aβ pathology – probably due to the amorphous, non-fibrillar nature of this cerebellar Aβ (Sabbagh et al., 2011).

A limitation of the present study is that because of the small group size, we are not powered to investigate the differences in APOEe4 allele distribution across groups. It is certainly possible that in addition to genetic differences related to APP and PS1 gene mutations, the APOEe4 allele could play a role in the differences in PiB retention.

The relevant question is whether these differences have any biological or clinical importance. Regarding the latter, there is no clear evidence of clinical manifestations of the increased striatal Aβ deposition. Although there are some clinical differences in certain ADAD mutations such as increased myoclonus, spastic paraparesis and increased seizures (Bateman et al., 2010) we have not observed this in our ADAD cohort. There was no evidence of significant motor symptoms in any the subjects included in this study. Although we previously identified a statistically significant association between the striatal PiB retention and executive cognitive function in a study of preADAD (McDade et al., 2014), others have not found neuropsychological associations with early caudate and thalamic volumetric changes(Ryan et al., 2013) in this population. We have previously reported striatal perfusion deficits using MRI in preADAD (McDade et al., 2014) indicating that, along with the previous studies showing both increased and decreased striatal tissue volumes(Fortea et al., 2010; Ryan et al., 2013), that early Aβ accumulation is likely not a completely benign process.

Given the early striatal differences noted in preADAD - found with structural MRI, amyloid PET and pathologic studies - we would speculate that a better understanding of the cause of this distinct anatomical difference will yield important clues to the contribution of early fibrillar Aβ accumulation and how the neuronal and non-neuronal CNS milieu may contribute to this process. Similar studies in DS will be necessary to see if there are alterations in volume, perfusion or cytoarchitecture of the subcortical structures similar to those found in ADAD. Ideally, these unique markers could be used to both identify additional targets of treatment of AD and possibly as a biomarker of response to therapies in early stage AD pathology in ADAD and DS prior to significant clinical symptoms. With the advent of tau markers it will become possible to better explore whether the early, increased striatal Aβ plaques are associated with distinct patterns of early neurofibrillary tau deposits, although existing postmortem studies in LOAD suggest neurofibrillary changes will not be prominent (Brilliant MJ, 1997; Suenaga T, 1990). Pathological studies in ADAD and DS have not identified clear differences in neurofibrillary tau deposition from late onset AD but these are restricted to those with late stage disease in all groups (Bateman et al., 2010; Lemere et al., 1996a; Mann et al., 1990).

Given the relationship of Aβ overproduction in DS and ADAD (Potter et al., 2013) with the consistent finding of early striatal Aβ using PiB-PET it is also worth considering whether this finding could be used in ongoing treatment trials in ADAD targeting Aβ in presymptomatic mutation carriers and DS in the near future. If the early striatal retention is fundamentally associated with an increase in Aβ production, as opposed to impaired clearance-which might play a greater role in LOAD-it is also possible that ADAD and DS might have an even greater likelihood of benefitting from drugs that target this overproduction prior to significant deposition and additional neurodegeneration.

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

We evaluated PiB-PET Aβ deposition patterns in four groups of subjects with evidence of cerebral β-amyloidosis.

Disorders associated with early-life alterations in APP production or processing are associated with a distinct pattern of early striatal fibrillary Aβ deposition prior to significant cognitive impairment. A better understanding of this unique pattern could identify important mechanisms of Aβ deposition and possibly important targets for early intervention.

Given the relationship of Aβ overproduction in DS and ADAD with the consistent finding of early striatal Aβ it is also worth considering whether this finding could be used in ongoing treatment trials in ADAD targeting Aβ in presymptomatic mutation carriers and DS in the near future. If early striatal retention is fundamentally associated with an increase in Aβ production, it is also possible that ADAD and DS might have an even greater likelihood of benefitting from drugs that target this overproduction.

Acknowledgments

Supported by The National Institutes of Health grants: P50 AG005133, RF1 AG025516, P01 AG025204, R01AG031110

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

Study Design: McDade, Cohen, Handen, Klunk

Manuscript preparation: McDade, Cohen

Statistical Analysis: McDade, Cohen

Manuscript review/revisions: Christian, Cohen, Klunk, Mathis, Price

Data Acquisition: Christian, Handen, Klunk

Disclosures:

Eric McDade- Has received research funding form Lilly, Roche, NIA; Advisory Board member for Lilly.

Annie Cohen -

Brad Christian-

Julie Price, PhD-

Chester Mathis-

William Klunk- GE Healthcare holds a license agreement with the University of Pittsburgh based on the technology described in this manuscript. Drs. Klunk and Mathis are co-inventors of PiB and, as such, have a financial interest in this license agreement. GE Healthcare provided no grant support for this study and had no role in the design or interpretation of results or preparation of this manuscript. All other authors have no conflicts of interest with this work and had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Benjamin L. Handen- Dr. Handen has received research funding from Curemark, Lilly, Roche, NIA and NICHD.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Unified segmentation. NeuroImage. 2005;26:839–851. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman R, et al. Autosomal-dominant Alzheimer’s disease: a review and proposal for the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy. 2010;3:1. doi: 10.1186/alzrt59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beacher F, et al. Alzheimer’s disease and Down’s syndrome: an in vivo MRI study. Psychol Med. 2009;39:675–84. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benzinger TL, et al. Regional variability of imaging biomarkers in autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E4502–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317918110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brilliant MJER, Ghobrial M, Struble RG. The distribution of amyloid beta protein deposition in the corpus striatum of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropathology & Applied Neurobiology. 1997;23:322–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AD, et al. Classification of amyloid-positivity in controls: Comparison of visual read and quantitative approaches. NeuroImage. 2013;71:207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleisher AS, et al. Florbetapir PET analysis of amyloid-β deposition in the presenilin 1 E280A autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease kindred: a cross-sectional study. The Lancet Neurology. 2012;11:1057–1065. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70227-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortea J, et al. Increased Cortical Thickness and Caudate Volume Precede Atrophy in PSEN1 Mutation Carriers. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2010;22:909–922. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuoka Y, et al. Histopathological studies on senile plaques in brains of patients with Down’s syndrome. Kobe J Med Sci. 1990;36:153–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gedye A. Dementia scale for Down’s syndrome: manual. Gedye Research and Consulting; Vancouver, BC: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Isla T, et al. The impact of different presenilin 1 andpresenilin 2 mutations on amyloid deposition, neurofibrillary changes and neuronal loss in the familial Alzheimer’s disease brain. 1999 doi: 10.1093/brain/122.9.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handen BL, et al. Imaging brain amyloid in nondemented young adults with Down syndrome using Pittsburgh compound B. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2012;8:496–501. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.09.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley SL, et al. Cognitive functioning in relation to brain amyloid-Beta in healthy adults with Down syndrome. 2014 doi: 10.1093/brain/awu173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, et al. The Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative (ADNI): MRI methods. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2008;27:685–691. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kida E, et al. Early amyloid-beta deposits show different immunoreactivity to the amino- and carboxy-terminal regions of beta-peptide in Alzheimer’s disease and Down’s syndrome brain. Neurosci Lett. 1995;193:105–8. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11678-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klunk WE, et al. Amyloid Deposition Begins in the Striatum of Presenilin-1 Mutation Carriers from Two Unrelated Pedigrees. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:6174–6184. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0730-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lao PJ, et al. The effects of normal aging on amyloid-beta deposition in nondemented adults with Down syndrome as imaged by carbon 11-labeled Pittsburgh compound B. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:380–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemere CA, et al. Sequence of Deposition of Heterogeneous Amyloid β-Peptides and APO E in Down Syndrome: Implications for Initial Events in Amyloid Plaque Formation. Neurobiology of Disease. 1996a;3:16–32. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1996.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemere CA, et al. The E280A presenilin 1 Alzheimer mutation produces increased A[beta]42 deposition and severe cerebellar pathology. Nat Med. 1996b;2:1146–1150. doi: 10.1038/nm1096-1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K, et al. Characterization of ABeta11-40/42 peptide deposition in Alzheimer’s disease and young Down’s syndrome brains: implication of N-terminally truncated ABeta species in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathologica. 2006;112:163–174. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopresti BJ, et al. Simplified Quantification of Pittsburgh Compound B Amyloid Imaging PET Studies: A Comparative Analysis. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2005;46:1959–1972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann DMA, et al. The prevalence of amyloid (A4) protein deposits within the cerebral and cerebellar cortex in Down’s syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathologica. 1990;80:318–327. doi: 10.1007/BF00294651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matveev SV, et al. Tritium-labeled (E, E)-2,5-bis(4′-hydroxy-3′-carboxystyryl)benzene as a probe for beta-amyloid fibrils. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2014;24:5534–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.09.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDade E, et al. Cerebral perfusion alterations and cerebral amyloid in autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2014;83:710–7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamee RL, et al. Consideration of optimal time window for Pittsburgh compound B PET summed uptake measurements. Journal of nuclear medicine: official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2009;50:348–55. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.057612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebes RD, et al. Cognitive aging in persons with minimal amyloid-beta and white matter hyperintensities. Neuropsychologia. 2013;51:2202–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pera M, et al. Distinct patterns of APP processing in the CNS in autosomal-dominant and sporadic Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;125:201–13. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1062-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. 2004;256:183–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter R, et al. Increased in Vivo Amyloid-Beta 42 Production, Exchange, and Loss in Presenilin Mutation Carriers. Science Translational Medicine. 2013;5:189ra77. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roid GH. Stanford-Binet Intellgence Test Scales. Riverside Publishing; Itasca, IL: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rosario BL, et al. Inter-rater reliability of manual and automated region-of-interest delineation for PiB PET. Neuroimage. 2011;55:933–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.12.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan NS, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging evidence for presymptomatic change in thalamus and caudate in familial Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2013;136:1399–1414. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbagh MN, et al. Positron emission tomography and neuropathologic estimates of fibrillar amyloid-beta in a patient with Down syndrome and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:1461–6. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara M, et al. Regional distribution of synaptic markers and APP correlate with distinct clinicopathological features in sporadic and familial Alzheimer’s disease. 2014 doi: 10.1093/brain/awu046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suenaga THA, Llena JF, Yen SH, Dickson DW. Modified Bielschowsky stain and immunohistochemical studies on striatal plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1990;80:280–286. doi: 10.1007/BF00294646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Um YH, et al. A Case Report of a 37-Year-Old Alzheimer’s Disease Patient with Prominent Striatum Amyloid Retention. Psychiatry Investig. 2017;14:521–524. doi: 10.4306/pi.2017.14.4.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villemagne VL, et al. High striatal amyloid beta-peptide deposition across different autosomal Alzheimer disease mutation types. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1537–44. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.