Abstract

Background

Short bowel syndrome occurs following massive small bowel resection (SBR) and is one of the most lethal diseases of childhood. We have previously demonstrated hepatic steatosis, altered gut microbiome, and increased fat deposition in our murine model of SBR. These novel findings prompted us to investigate potential alterations in glucose metabolism and systemic inflammation following intestinal resection.

Methods

Male C57BL6 mice underwent 50% proximal SBR or sham operation. Body weight and composition were measured. Fasting blood glucose (FBG), glucose, and insulin tolerance testing were performed. Small bowel, pancreas, and serum were collected at sacrifice and analyzed.

Results

SBR mice gained less weight than shams after 10 weeks. Despite this, FBG in resected mice was significantly higher than sham animals. After SBR, mice demonstrated perturbed body composition, higher blood glucose, increased pancreatic islet area, and increased systemic inflammation compared with sham mice. Despite these changes, we found no alteration in insulin tolerance after resection.

Conclusions

After massive SBR, we present evidence for abnormal body composition, glucose metabolism, and systemic inflammation. These findings, coupled with resection-associated hepatic steatosis, suggest that massive SBR (independent of parenteral nutrition) results in metabolic consequences not previously described and provides further evidence to support the presence of a novel resection-associated metabolic syndrome.

Keywords: Small bowel resection, Short bowel syndrome, Hepatic steatosis

I. Introduction

Short bowel syndrome is a massive loss of small bowel due to surgical resection for acquired or congenital conditions in children and adults. Short bowel syndrome has been associated with several long-term changes including hepatic dysfunction and short stature[1, 2]. Data regarding body composition in pediatric SGS patients are sparse. In a recent study of 34 children with intestinal failure from a variety of causes, those who required PN had a significant deficit in lean limb mass with greater fat mass indices, the latter effect related to the amount of PN needed[2]. In another report, the body composition of pediatric SGS patients who had all weaned successfully from PN were compared with reference standards[3]. In this cohort, height and lean body mass were significantly lower while % body fat was normal. These findings are analogous to our murine SBR model that demonstrates a perturbed body composition phenotype as mice recover from massive small bowel resection (SBR) in the absence of PN.

In mouse models, the combination of obesity and elevated fasting blood glucose is routinely used to study the renowned metabolic syndrome (MeS). The diagnosis of MeS has significant implications on morbidity and mortality with increased risk of cardiovascular events, type II diabetes (DMII), and death [4, 5]. In addition to the diagnostic features and cardiovascular consequences, systemic inflammation and pathologic triglyceride accumulation in the liver is often seen in humans and mice with MeS[6]. Similar to MeS, data demonstrate that perturbations in glucose homeostasis are linked to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)[7]. In addition to changes in body composition, previous studies from our lab have found that mice develop hepatic steatosis 10 weeks after small bowel resection [8]. Given our findings of altered body composition and development of steatosis resembling models of MeS and NAFLD, the purpose of this study was to test the hypothesis that massive intestinal resection results in perturbed glucose homeostasis due to a systemic proinflammatory response.

II. Methods

Animals

C57BL6 mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) at 7 weeks of age. Mice were housed on arrival in a facility with a 12-h light/dark cycle. Male mice were used exclusively in order to limit known hormonal confounders on the timing and severity NAFLD [9]. Food and water were provided ad libitum to SBR animals and sham animals were provided the same amount of food as SBR cages. This study was approved by the Washington University Animal Studies Committee (Protocol #20130308) in accordance with the National Institute of Health laboratory animal care and use guidelines.

Operations and Sample Collection

All operated mice underwent a 50% proximal SBR or sham operation as we have previously described.[10] Briefly, through a midline laparotomy the bowel is exteriorized and then transected 12cm from the terminal ileum and 2–3cm from the pylorus. The intervening mesentery was ligated with silk suture and a hand sewn, end-to-end anastomosis was performed with interrupted 9-0 nylon sutures. For sham operations, the proximal bowel was transected 12cm from the terminal ileum and reaanastomosis performed (no resection). Animals were fasted for the first 24 hours post operatively then returned to standard liquid diet (LD; PMI Micro-Stabilized Rodent Liquid Diet LD 101; TestDiet, St. Louis MO). Animals were sacrificed at 5 or 10 weeks after operation. The small intestine, pancreas, and serum were collected.

Glucose and Insulin Tolerance Testing

Insulin and glucose tolerance tests were performed as previously described[11, 12]. Animals were acclimated to the tester by handling of the animals for 2 days prior to experimentation. Animals were fasted overnight (18h) on wood chip bedding. Animals were weighed and tails clipped then rested for 1 hour in a heated, low stimulation environment. Mice were then given a 2mg/g glucose load either intraperitoneally (IPGTT) or via oral gavage (OGTT). For insulin tolerance testing an intraperitoneal injection of human regular insulin (Eli Lilly and Co., Indianapolis, Indiana, USA) at a dose of 0.75 U/kg body weight. Tail vein blood glucose was measured at times 0, 15, 30, 60, and 90 minutes. Animals were excluded from GTT if they failed to demonstrate a glucose peak or demonstrated a late persistent peak (>500) consistent with a stress response. Tests were performed at both 5 and 10 weeks following SBR.

Body Composition

Given that the hepatic steatosis we observed occurs at a later time point than we have previously studied, we chose to look at the late changes in body composition by comparing measurements at 10 weeks to those at 5 weeks. Body composition was measured by MRI as previously described [13].

Histology and Islet quantification

Pancreas sections were fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sections stained with Hematoxylin and eosin. Slides were scanned at 10X magnification. Quantification of total pancreas area and islet area was performed in Image-J software. All slides were analyzed by the same investigator and blinded for group.

Inflammatory cytokines

The Mesoscale Discovery VPLEX Proinflammatory Panel 1 (mouse) kit (Catalog#K15408) with reagents for the detection of interleukin 1-beta (IL-1β), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) was used to investigate serum cytokine levels at 10 weeks after small bowel resection. Samples were prepared according to the manufacturer protocol. Electrochemiluminescence (ECL) was measured and reported as emitted fluorescence intensity. Data analysis was performed using the MSD Discovery Workbench analysis software.

Statistics

Graphs and statistical analysis were performed using Graphpad-Prism. Glucose tolerance tests were analyzed using 2-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Sidak’s multiple comparisons. We chose this statistical method because we obtained multiple measures from the same subjects for tolerance testing. Fasting blood glucose, serum cytokines, body composition and pancreatic islet mass were analyzed using Student’s t-test. A p value <0.05 was considered significant. All analyses presented were calculated using G*Power software and had a measured power of 0.80 or greater[14].

III. Results

Weight

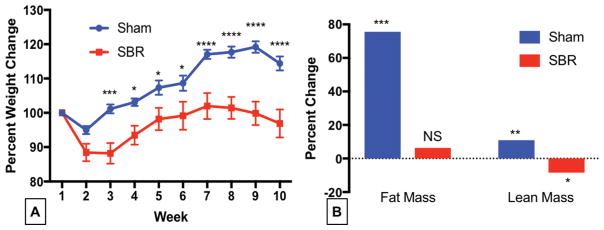

Resected mice gained 13% less body weight compared with shams after 5 weeks (100.7% vs. 115.1% of baseline weight p<0.0001;). Postoperatively sham mice lost 3% of their total body weight while SBR mice lost 10%. Sham mice surpassed their baseline starting weight by week 2 while SBR mice did not achieve this level until four weeks post operatively (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mice gain significantly less weight, maintaining fat mass and losing lean mass after 50% small bowel resection (SBR) compared with sham operated animals. Male C57BL6 mice underwent 50% proximal SBR or sham operation. (A) They were weighed weekly for 10 weeks. (B) Body composition obtained at week 10 was compared to that obtained at week five to visualize late body composition change. ANOVA for operation p< 0.0002. Sidak’s Multiple comparisons presented on weight graph. *p <0.05, **p=0.001,*** p <0.0007, **** p <0.0001, N= 9–14

Body composition

Sham operated mice gained significant fat (75.5 %, p<0.001) and lean mass (10.9 % p=0.001) when comparing body composition 5 weeks to body composition at 10 weeks after operation. On the other hand, following SBR, mice maintained their fat mass over the later time period but lost lean mass (8.4% p<0.05). (Figure 1B)

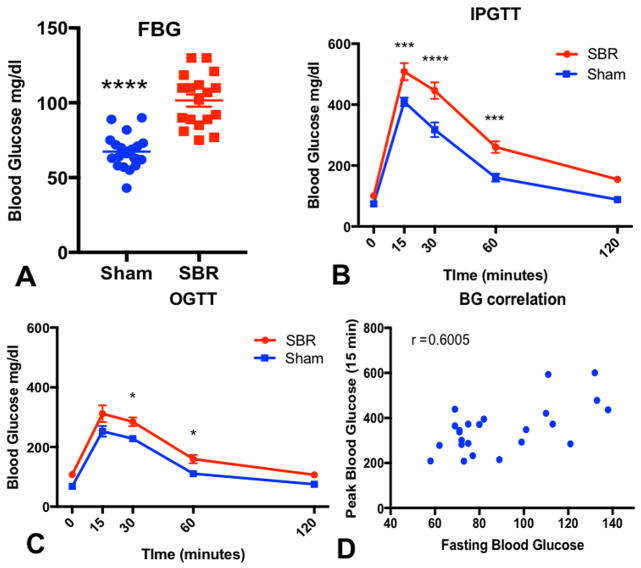

Blood glucose and Glucose Tolerance Testing at 5 weeks postoperatively

Fasting blood glucose levels in resected mice were 40% higher than in sham operated animals (101.6 ± 4.12, n=17 vs. 67.4 ± 2.67, n=18–19, p<0.0001, Figure 2A). After IP administration of glucose, SBR mice demonstrated significantly higher blood glucose at fifteen, thirty, and sixty minutes when compared to sham operated mice (Figure 2B). The same trend was further confirmed with oral glucose administration as indicated in Figure 2C. Two-way ANOVA demonstrated significance for both GTT studies when analyzing operation type (p<0.002 for OGTT, p<0.0001 for IGTT) demonstrating a significant difference in the overall trend of glucose tolerance between the groups (Figures 2B–C). Additionally, we found that fasting blood glucose positively correlates with 15 minute (r=0.60, p<0.002) and peak blood glucose levels (r=0.85, p<0.001, Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Glucose homeostasis is impaired 5 weeks after massive small bowel resection (SBR). Male C57BL6 mice underwent 50% proximal SBR or sham operation. Fasting blood glucose (FBG, A) was measured after overnight fast and after a 2mg/g body weight glucose load provided by either intraperitoneal (IPGTT, B) or oral gavage (OGTT, C). Finally, (D) Peak blood glucose levels directly correlated to fasting blood glucose. ANOVA was used to analyze trends over time comparing operations. P<0.0002 for IPGTT and P< 0.002 for oral GTT. Sidak’s multiple comparisons are presented on charts. *p <0.05, **p <0.001, ***p <0.0003, ****p <0.0001, n=18–19 for FBG, n=5–8 for GTT, n=13 pairs for correlation

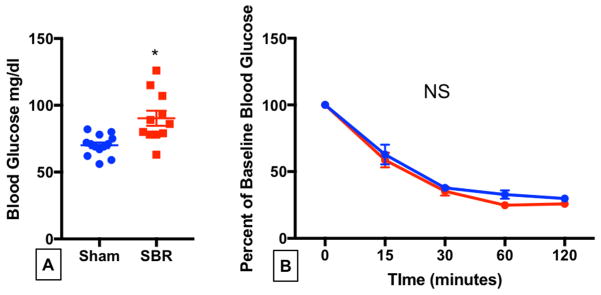

Insulin Tolerance Testing at 10 weeks postoperatively

Elevated fasting blood glucose levels persisted after SBR when compared with sham operated mice at 10 weeks following operation (Figure 3A). We next investigated insulin tolerance. We found no change in peripheral insulin resistance after SBR since there were no differences in blood glucose levels after insulin administration between the two groups at any time point. (Figure 3B)

Figure 3.

Fasting blood glucose remains elevated at 10 weeks after small bowel resection without alteration of peripheral insulin tolerance. Male C57BL6 mice underwent 50% proximal SBR or sham operation. At 10 weeks after operation, (A) fasting blood glucose was measured after overnight fast. (B) Mice were given a 0.75 U/kg body weight insulin load via intraperitoneal injection and blood glucose was determined over the course of 120 minutes. *p=0.002, N=11–13 for FBG, N=5–9 for ITT

Pancreas Histology

SBR mice demonstrated 65% increase in islet area (islet area/total pancreatic area) compared to sham mice (p= 0.0091) (Figure 4A–B).

Figure 4.

Pancreatic islet area is significantly increased after massive SBR.

Male C57BL6 mice underwent sham operation A) or 50% proximal small bowel resection (SBR) and were sacrificed at 5 weeks after operation. Tissue was fixed in formalin, paraffin embedded, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Slides are presented at 10X magnification. A) Representative microscopic section of pancreas from Sham operated mouse. Arrowheads denote islets. B) Representative microscopic section of pancreas from mouse at 5 weeks following SBR. Arrowheads denote islets. C) Quantification of total pancreas area and islet area was performed in Image-J software (C). *p<0.01 n=4–7.

Serum Cytokines

We next analyzed serum at 5 weeks and 10 weeks post operatively for TNFα, IL-6 and IL-1β. We found a trend toward increased cytokines in resected mice, but only TNFα demonstrated a significant difference. Resected mice had 40% more TNFα at 10 weeks compared to sham operated animals (9.242 ± 1.186 vs 6.161 ± 0.5207, n=9–13, Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Small bowel resection results in elevated TNF α at 10 weeks after small bowel resection. Male C57BL6 mice underwent sham operation, A) or 50% proximal small bowel resection (SBR). Serum was collected via cardiac puncture at the time of sacrifice (10 weeks after operation). Serum was analyzed for TNFα, IL-6 and IL-1β using an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay. P<0.05, N= 4–13 (sham), N=9 (SBR)

Discussion

In the present study using a PN-independent model of short bowel syndrome, we have demonstrated that that mice recover less weight than their sham counterparts preserving fat stores at the cost of lean mass. Further, SBR is associated with elevated fasting blood glucose and significantly higher peak glucose in response to a glucose load, but do not demonstrate peripheral insulin resistance. Finally, resected mice demonstrate elevated serum TNFα levels at 10 weeks following operation. Taken together, these findings suggest that the metabolic consequences of massive small bowel loss create similar pathogenic conditions to those of MeS and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). However, with the lack of peripheral insulin resistance and increased BMI, it lacks key pathophysiological components to be identified as either of the previously described syndromes.

In our study, mice achieved baseline weight but weighed significantly less than the sham operated animals by 10 weeks. Given that obesity is such a strong predictor of diabetes[15], finding elevated fasting blood glucose in the resected mice was quite unexpected. In losing 50% of the small bowel, these mice have lost half of the largest endocrine organ in the body; an organ which has been shown to contribute significantly to glucose homeostasis [16]. One of the most effective methods of shifting the hormonal control of glucose homeostasis is to alter the intestinal anatomy. Bariatric operations that bypass, but do not remove intestinal length have increase insulin sensitivity and correct hyperglycemia before substantial weight loss has occurred (reviewed [17]). Although weight loss occurs after both SBR and intestinal bypass, the SBR phenotype is distinctive as fat stores are maintained while lean body mass declines. Further, glucose homeostasis is corrected with gastric bypass while glucose intolerance occurs after SBR.

Previous studies using our murine model have revealed hepatic steatosis at 10 weeks after SBR [8]. We therefore hypothesized that this finding might involve systemic inflammation similar to the presumed pathogenesis of NAFLD [18]. In agreement with this consideration, we found elevated serum TNFα levels at 10 weeks after SBR. Although previous studies have shown that TNFα results in decreased insulin sensitivity via inhibition of insulin signaling [19] our insulin tolerance test experiments did not confirm that the abnormal glucose metabolism was due to insulin insensitivity. Further studies will be required to determine the mechanism for abnormal glucose homeostasis after SBR and include abnormal glucose production, perhaps mediated by elevated pancreatic glucagon secretion. Along these lines, pancreatic glucagon response to arginine administration has previously been shown to be abnormal in short gut patients [20].

One of the major limitations of this study is the single method by which insulin sensitivity has been tested. Our aim in performing ITT at 10 weeks was to explore any differences between the known pathogenesis of MeS and NAFLD and the metabolic consequences we have observed after SBR. Our finding of no difference in peripheral insulin resistance calls for additional study of beta cell function and insulin signaling after SBR.

The pancreatic islets contain beta cells which are responsible for insulin production. In a prior study, rats underwent 50% mid-SBR and an increase in islet cell mass with increased beta cell proliferation was observed at 5 months after operation[21]. These findings agree with our data, but do not describe the function of the hypertrophied islets. The mechanism of altered pancreatic function after SBR is not well understood, but has been reported in studies of humans and dogs where intolerance to oral glucose and impaired plasma insulin response after proximal SBR has been observed [20, 22, 23]. While hypertrophy of the islets has been described in several models, the etiology of the paradoxical decrease in function remains poorly understood. The next step in our studies involves characterizing the cells within the islets of resected mice, both structure and function.

In the liver, insulin drives glycogen synthase and inhibits gluconeogenesis contributing to insulin’s hypoglycemic effects. In hepatic insulin resistance, these effects are severely blunted. Hepatic steatosis (NAFLD), has been shown to drive hepatic insulin resistance and is associated with both obesity and systemic insulin resistance (reviewed in [24]). Given that we have observed significant hepatic steatosis in our short bowel mouse model[8], it is not unreasonable to hypothesize that hepatic insulin resistance may be contributing to the glucose intolerance observed in this study. We plan to test the gluconeogenic capacity of mice after SBR as hepatic insulin resistance may contribute to both the elevated FBG as well as the lack of peripheral insulin resistance.

Delineating whether the mechanisms behind hepatic steatosis are at least in part the same as those which drive MeS and NAFLD offers a tremendous therapeutic advantage to patients with short bowel syndrome. Previous studies have demonstrated that improved glycemic control results in improvements in both biochemical and histological evidence of NAFLD and NASH[25]. In children, 60% of the deaths from SBS are the result of hepatic injury leading to intestinal failure-associated liver disease(IFALD)[26]. The medical therapies utilized to achieve glycemic control may offer this population a survival benefit.

Our murine model for SBR does not involve PN, a major factor considered in the pathogenesis of IFALD. Parenteral nutrition has many components that have been implicated in resection-associated liver injury such as rate of glucose infusion, type of parenteral fat (omega 6 versus omega 3), and type of amino acids [27]. Despite the lack of PN, we have shown that intestinal resection alone is associated with significant abnormalities in glucose metabolism as demonstrated by elevated fasting blood glucose levels, abnormal responses to both enteral and systemic glucose administration, and pancreatic islet cell hyperplasia. Taken together, the findings of the present investigation reveal a novel resection-associated metabolic syndrome (RAMS). The RAMS response warrants further investigation as this may elucidate key mechanistic pathways in the pathogenesis of stunted growth (lower lean body mass) and liver disease that occurs in patients suffering from short gut syndrome.

Conclusions

After massive SBR and in the absence of PN, mice have elevated fasting blood glucose, glucose intolerance, increased systemic inflammation, but not peripheral insulin resistance. Resected mice also demonstrate significant increases in pancreatic islet area compared to sham operated mice. Further research is underway to delineate the mechanisms behind these observations in the rodent model of massive small bowel resection.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (F32DK103490 – Dr. Barron), 5T32CA00962128 (Dr. Panni), The St. Louis Children’s Hospital Foundation Children’s Surgical Sciences Research Institute, The Digestive Disease Research Core Center (NIH# P30DK052574), The Andrew M. and Jane M. Bursky Center for Human Immunology and Immunotherapy Programs at Washington University, Immunomonitoring Laboratory. We would like to thank Dr. Diane Bender for her expertise in cytokine analysis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kelly DA. Intestinal failure-associated liver disease: what do we know today? Gastroenterology. 2006;130:S70–77. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.10.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pichler J, Chomtho S, Fewtrell M, et al. Body composition in paediatric intestinal failure patients receiving long-term parenteral nutrition. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99:147–153. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-303516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olieman JF, Penning C, Spoel M, et al. Long-term impact of infantile short bowel syndrome on nutritional status and growth. Br J Nutr. 2012;107:1489–1497. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511004582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galassi A, Reynolds K, He J. Metabolic syndrome and risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2006;119:812–819. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ford ES. Risks for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes associated with the metabolic syndrome: a summary of the evidence. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1769–1778. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.7.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sinasac DS, Riordan JD, Spiezio SH, et al. Genetic control of obesity, glucose homeostasis, dyslipidemia and fatty liver in a mouse model of diet-induced metabolic syndrome. Int J Obes (Lond) 2016;40:346–355. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2015.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marchesini G, Brizi M, Morselli-Labate AM, et al. Association of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with insulin resistance. The American Journal of Medicine. 1999;107:450–455. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00271-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barron LK, Gayer CP, Roberts A, et al. Liver steatosis induced by small bowel resection is prevented by oral vancomycin. Surgery. 2016;160:1485–1495. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2016.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hewitt KN, Pratis K, Jones ME, et al. Estrogen replacement reverses the hepatic steatosis phenotype in the male aromatase knockout mouse. Endocrinology. 2004;145:1842–1848. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helmrath MA, VanderKolk WE, Can G, et al. Intestinal adaptation following massive small bowel resection in the mouse. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;183:441–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li B, Nolte LA, Ju JS, et al. Skeletal muscle respiratory uncoupling prevents diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance in mice. Nat Med. 2000;6:1115–1120. doi: 10.1038/80450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonaventura MM, Crivello M, Ferreira ML, et al. Effects of GABAB receptor agonists and antagonists on glycemia regulation in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;677:188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tantemsapya N, Meinzner-Derr J, Erwin CR, et al. Body composition and metabolic changes associated with massive intestinal resection in mice. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, et al. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175–191. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wild SH, Byrne CD. Risk factors for diabetes and coronary heart disease. BMJ. 2006;333:1009–1011. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39024.568738.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim W, Egan JM. The role of incretins in glucose homeostasis and diabetes treatment. Pharmacol Rev. 2008;60:470–512. doi: 10.1124/pr.108.000604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamvissi-Lorenz V, Raffaelli M, Bornstein S, et al. Role of the Gut on Glucose Homeostasis: Lesson Learned from Metabolic Surgery. Current Atherosclerosis Reports. 2017;19 doi: 10.1007/s11883-017-0642-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stojsavljević S, Gomerčić Palčić M, Virović Jukić L, et al. Adipokines and proinflammatory cytokines, the key mediators in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:18070–18091. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i48.18070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plomgaard P, Bouzakri K, Krogh-Madsen R, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces skeletal muscle insulin resistance in healthy human subjects via inhibition of Akt substrate 160 phosphorylation. Diabetes. 2005;54:2939–2945. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.10.2939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kajawara T, Szuki T, Tobe T. Effect of massive bowel resection on enteroinsular axis. Gut. 1979;20:806–810. doi: 10.1136/gut.20.9.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perez-Arana G, Camacho-Ramirez A, Segundo-Iglesias MC, et al. A surgical model of short bowel syndrome induces a long-lasting increase in pancreatic beta-cell mass. Histol Histopathol. 2015;30:479–487. doi: 10.14670/HH-30.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleck U, Nowak W, Senf L. Short bowel syndrome and glucose tolerance. Gastroenterol J. 1989;49:102–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tamura K, Kajiwara T, Suzuki T, et al. Functional alteration of islet cells after jejunal or ileal resection in dogs. Diabetes. 1978;27:1156–1166. doi: 10.2337/diab.27.12.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perry RJ, Samuel VT, Petersen KF, et al. The role of hepatic lipids in hepatic insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2014;510:84–91. doi: 10.1038/nature13478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhatt HB, Smith RJ. Fatty liver disease in diabetes mellitus. Hepatobiliary Surgery and Nutrition. 2015;4:101–108. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2304-3881.2015.01.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wales PW, Christison-Lagay ER. Short bowel syndrome: epidemiology and etiology. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2010;19:3–9. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Courtney CM, Warner BW. Pediatric intestinal failure-associated liver disease. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2017;29:363–370. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]