Abstract

Identifying molecules that are differentially expressed in encephalitogenic T cells is critical to the development of novel and specific therapies for multiple sclerosis (MS). In this study, IL-3 was identified as a molecule highly expressed in encephalitogenic Th1 and Th17 cells, but not in myelin-specific non-encephalitogenic Th1 and Th17 cells. However, B10.PL IL-3-deficient mice remained susceptible to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a mouse model of MS. Furthermore, B10.PL myelin-specific T cell receptor transgenic IL-3−/− Th1 and Th17 cells were capable of transferring EAE to wild-type mice. Antibody neutralization of IL-3 produced by encephalitogenic Th1 and Th17 cells failed to alter their ability to transfer EAE. Thus, IL-3 is highly expressed in myelin-specific T cells capable of inducing EAE compared to activated, non-encephalitogenic myelin-specific T cells. However, loss of IL-3 in encephalitogenic T cells does not reduce their pathogenicity, indicating that IL-3 is a marker of encephalitogenic T cells, but not a critical element in their pathogenic capacity.

Keywords: multiple sclerosis, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, IL-3, GM-CSF, Th1 cells, Th17 cells

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a CNS demyelinating disease that is postulated to be mediated by encephalitogenic CD4+ T cells reactive to myelin (1). Most individuals harbor myelin-reactive T cells, illustrating that the mere presence of myelin-specific T cells is insufficient to cause MS (2–4). It is still unclear what characteristics of a myelin-specific T cell make them encephalitogenic and capable of mediating CNS pathology. Identifying molecules that are differentially expressed in encephalitogenic T cells is critical to understanding how they mediate pathology, as well as identifying new and specific therapeutic targets for MS. IL-3 is a molecule that is primarily produced by activated T-cells (5), but plays a critical role in the activation and survival of a diverse group of cells, including mast cells and basophils, monocytes, B cells, T cells, and endothelial cells (6–13). Studies have shown that IL-3 contributes to inflammation and autoimmunity (14–16). The Il3 gene is located on chromosome 11 in mice and chromosome 5 in humans, within the same gene cluster as Csf2, the gene coding GM-CSF. There is a potential binding site for the transcriptional factor T-bet close to this gene cluster. T-bet and GM-CSF have been shown to be associated with EAE development (17–24), and so it is possible that the activation of this gene cluster is a contributing factor to T cell encephalitogenicity. A previous study found that increased IL-3 expression by CD4+ T cells is associated with relapses in MS patients, encephalitogenic CD4+ T cells are the primary source of IL-3 in EAE, and the administration of IL-3 to mice with EAE exacerbates disease (16, 25). IL-3 has also been identified as a signature gene of pathogenic Th17 cells in EAE (26), and IL-3 was shown to be higher in myelin tetramer-positive memory T cells from MS patients (27). In this study, we analyze the role of IL-3 produced by T cells in EAE using B10.PL mice and myelin-specific T cell receptor (TCR) transgenic cells, which allows us to efficiently generate encephalitogenic and non-encephalitogenic T cells with a single in vitro stimulation so that we can compare the role of IL-3 in T cell encephalitogenicity (28).

Materials and Methods

Animals

IL-3−/− mice (29) were backcrossed >8 generations onto the B10.PL background and MBP Ac1-11-specific TCR transgenic mice (30). The protocols used for these experiments received approval by the OSU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were conducted in accordance with the US Public Health Service’s Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

In Vitro Culture of Splenocytes

Splenocytes were isolated from 6- to 8-week TCR transgenic mice and cultured in 24-well plates at 1.5 × 106 cells/well with irradiated splenocytes (feeder cells) from wild-type mice at a concentration of 4.5 × 106 cells/well and MBP Ac1-11 peptide (2 µg/mL). Th17 cells were induced by adding IL-6 (25 ng/mL) plus anti-IL4 (1 μg/mL; 30340), anti-IL12 (0.5 µg/mL; polyclonal goat IgG), and anti-IFNγ (2 μg/mL; H22) to the cultures or IL-6 + TGFβ (1 ng/mL). Th1 cells were induced by adding IL-12 (0.5 ng/mL) to the cultures or activating the T cells with anti-CD3/CD28 (145-2C11 and 37.51, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA)-coated plates plus IL-12 (0.5 ng/mL). Antibodies and cytokines were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Some cells were treated with IL-3-neutralizing antibody (2 μg/mL; MP2-8F8, BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA).

ELISA

The following antibodies were used: IL-3 capture (MP2-8F8) and biotinylated IL-3 detection (MP2-43D11) (BioLegend), IL-17 capture (eBio17CK15A5) and biotinylated IL-17 detection (eBio17B7) (eBioscience, Waltham, MA, USA), IFNγ capture (R46A2) and biotinylated IFNγ detection (XMG1.2) (BD Biosciences), and GM-CSF capture (MP122E9) and biotinylated GM-CSF detection (polyclonal goat IgG) (R&D Systems) were used. The ELISA was performed as previously described (30).

EAE Induction

Active induction of EAE was performed by subcutaneous injection of naïve 6–8 week B10.PL IL-3−/−, IL-3+/−, and IL-3+/+ littermate mice over four sites in the flanks with 200 µg MBP Ac1-11 (CS Bio, Menlo Park, CA, USA) emulsed in CFA (Difco, Becton Dickinson Co., Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Pertussis toxin (200 ng) (List Biological Laboratories, Campbell, CA, USA) was injected i.p. at the time of immunization and 48 h later. For adoptive transfer EAE, splenocytes were isolated from 6- to 8-week IL-3−/−, IL-3+/−, and IL-3+/+ TCR transgenic mice. Cells were activated in vitro as described above, collected at 72 h, and 5 × 106 cells were injected i.p. into B10.PL mice. Mice were evaluated daily for signs of EAE: 0, no clinical disease; 1, limp/flaccid tail; 2, moderate hind limb weakness; 3, severe hind limb weakness; 4, complete hind limb paralysis; 5 quadriplegia or premoribund state; and 6, death.

Flow Cytometry

Cells were collected, washed, and resuspended in staining buffer (1% BSA in PBS) and incubated with Fc blocker (93, BioLegend) for 10 min at 4°C. Cells were then stained for cell-surface markers for 30 min at 4°C. After washing twice with buffer, cells were fixed and permeabilized using Cytofix/Cytoperm solution (BD Biosciences) for 20 min at 4°C. Cells were stained for intracellular cytokines with Ab diluted in Perm/Wash solution (BD Biosciences) for 30 min at 4°C. After washing twice with Perm/Wash buffer, the cells were resuspended in 200 µL of buffer. Approximately 100,000 cell events were acquired on a FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OH, USA). Pacific Blue-anti-CD4 (RM4-5), FITC-anti-CD44 (IM7), PE-anti-IL-3 (MP2-8F8), PE-anti-GM-CSF (MP1-22E9), APC-anti-IFNγ (XMG1.2), and PE-anti-IL-17 (TC11-18H10) were obtained from BD Bioscience.

Results

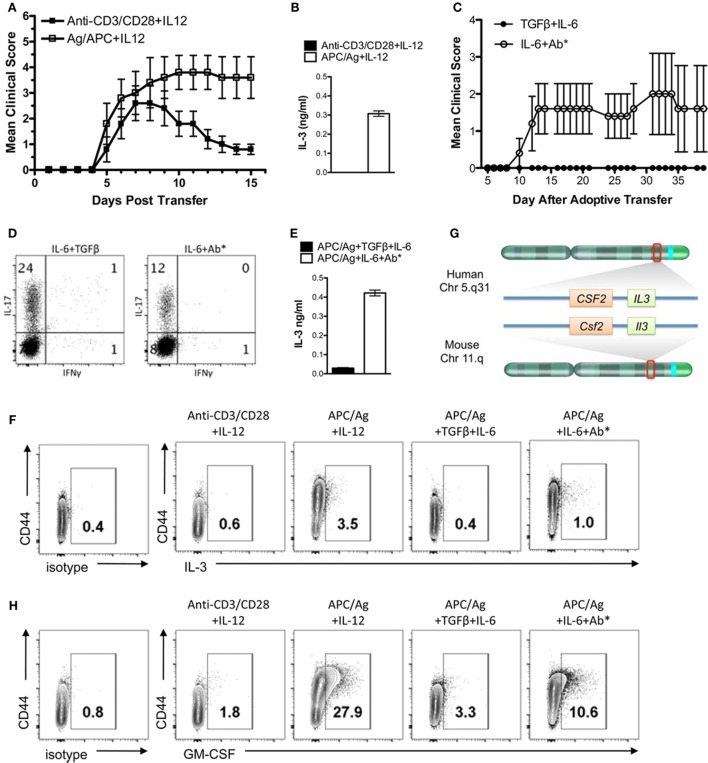

The encephalitogenicity of myelin-specific T cells varies using different in vitro activation protocols. In Figure 1A, naïve myelin-specific T cells from a MBP Ac1-11-specific TCR transgenic mouse were differentiated with anti-CD3/CD28 + IL-12 or APCs + MBP Ac1-11 peptide + IL-12 to generate myelin-specific Th1 cells. Th1 cells differentiated with APC/Ag + IL-12 were highly encephalitogenic, while the myelin-specific Th1 cells differentiated with anti-CD3/CD28 + IL-12 were significantly less encephalitogenic. Analysis of IL-3 by these Th1 cells found that IL-3 expression was significantly elevated in these APC/Ag-driven Th1 cells (Figure 1B). Similarly, myelin-specific Th17 cells differentiated with APC/Ag + IL-6 + TGFβ were not encephalitogenic, while differentiation of MBP-specific TCR transgenic T cells into Th17 with APC/Ag + IL-6 + anti-IL4/IL12/IFNγ were highly encephalitogenic (Figures 1C,D), consistent with previous studies (22, 28, 31–34). Similar to the encephalitogenic Th1 cells, IL-3 was highly expressed in the encephalitogenic Th17 cells (Figure 1E). The percentage of IL-3+ cells in the activated CD4+ T cell population was enhanced in the encephalitogenic Th1 and Th17 cells (Figure 1F). Since the Il3 allele is located in the same gene cluster with Csf2 (encodes GM-CSF) on chromosome 11 in mouse and chromosome 5 in human (Figure 1G) and GM-CSF was found to be critical for encephalitogenic T cells (17, 21, 23, 24), we analyzed GM-CSF+-activated CD4 T cells via flow cytometry. As expected, GM-CSF+ cells were increased in encephalitogenic Th1 and Th17 cells (Figure 1H). Given that Il3 and Csf2 are in the same gene cluster, it is unclear whether increased IL-3 is due to a specific upregulation of the Il3 gene or an indirect effect due to upregulation of the Il3/Csf2 gene cluster.

Figure 1.

IL-3 is highly expressed in encephalitogenic Th1 and Th17 cells. Splenocytes from naïve MBP-specific T cell receptor Tg mice were differentiated into Th1 cells with plate-bound anti-CD3/28 Ab plus IL-12 or antigen-presenting cell (APC)/Ag plus IL-12. Th17 cells were differentiated with APC/Ag plus IL-6 + TGF-β or APC/Ag plus IL-6 + anti-IL4/IL12/IFNγ. (A,C) Cells were collected and transferred into B10.PL mice (5 × 106 cells/mouse). Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis clinical scores were monitored daily. Data are representative of three independent experiments (mean ± SEM). **p < 0.01, Mann–Whitney U test. (B,E) Supernatants were analyzed by ELISA for IL-3. (D) Flow cytometric analysis of IL-17 and IFNγ in Th17 cells. (F) IL-3 and (H) GM-CSF were stained intracellularly and analyzed by flow cytometry (gated on CD4+ cells). (G) Illustration of IL-3 and GM-CSF loci in mouse and human chromosomes.

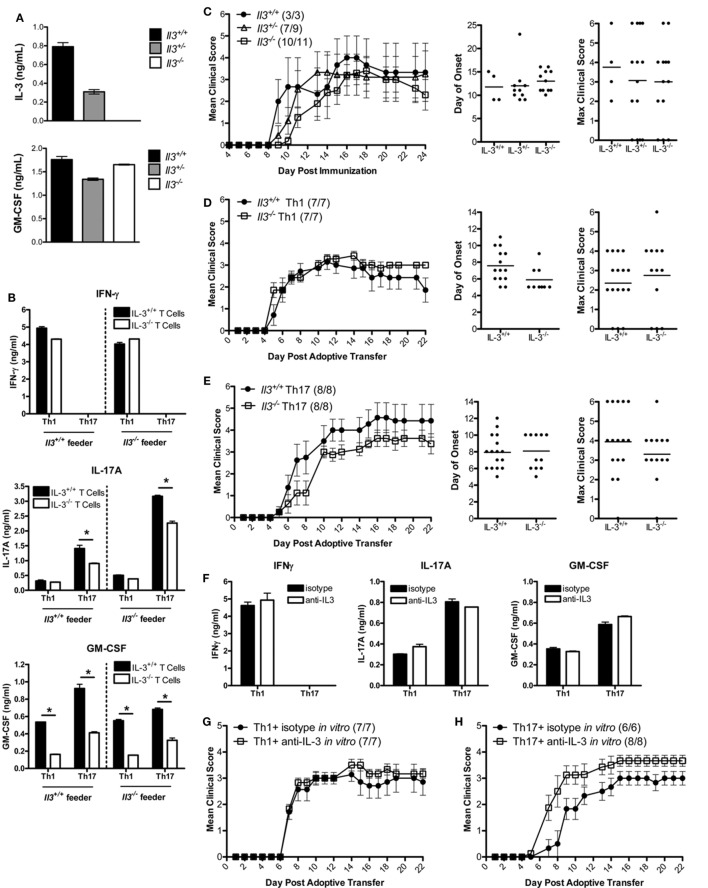

To determine whether IL-3 was critical in the encephalitogenic capacity of myelin-specific T cells, IL-3-deficient mice were backcrossed with the B10.PL MBP-specific TCR transgenic mice. Since the Il3 and Csf2 alleles are in close proximity, we needed to confirm that deletion of Il3 gene did not result in a loss of Csf2 gene expression. IL-3+/+, IL-3+/−, and IL-3−/− splenocytes were activated with MBP Ac1-11 in vitro, and IL-3 and GM-CSF levels were analyzed by ELISA. GM-CSF levels were not significantly changed in the IL-3+/− or IL-3−/− splenocytes, indicating that Csf2 gene expression was intact (Figure 2A). To determine if IL-3 deficiency influenced Th1 and Th17 cell differentiation, the myelin-specific T cells were differentiated under Th1 and Th17 conditions in vitro and analyzed for cytokine production by ELISA. Since APCs also produce IL-3, crisscross cultures were set up with myelin-specific IL-3+/+ and IL-3−/− T cells cocultured with IL-3+/+ and IL-3−/− APCs (feeder cells) under encephalitogenic Th1 and Th17 conditions (Figure 2B). For Th1 cells, IFNγ levels were not significantly changed, but there was a reduction in GM-CSF levels. There was no difference between Th1 cells cultured with IL-3+/+ or IL-3−/− APCs. There was a reduction in IL-17 and GM-CSF levels in the Th17 cells, and surprisingly IL-17 expression was higher with IL-3−/− APCs. The reduction in GM-CSF in both the Th1 and Th17 cells was suggestive of reduced encephalitogenicity since GM-CSF was found to be essential in encephalitogenic T cells.

Figure 2.

IL-3 is not required for T cell encephalitogenicity. (A) Splenocytes from naïve Il3+/+, Il3+/−, and Il3−/− MBP-specific T cell receptor (TCR) Tg mice were activated with MBP Ac1-11 and feeder cells without exogenous cytokines in vitro for 3 days. Supernatants were collected and analyzed by ELISA for IL-3 and GM-CSF. (B) Il3+/+ or Il3−/− TCR Tg splenocytes were cocultured with Il3+/+ or Il3−/− feeder cells in the presence of MBP Ac1-11 peptide in vitro for 3 days. Encephalitogenic Th1 cells were differentiated with IL-12, and encephalitogenic Th17 cells were differentiated with IL-6 + anti-IL4/IL12/IFNγ. Supernatants were analyzed by ELISA for IFNγ, IL-17A, and GM-CSF. *p < 0.05, unpaired Student’s t-test. (C) Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) was induced by immunization of B10.PL Il3+/+ Il3+/− and Il3−/− mice with MBP Ac1-11/CFA. Disease incidence is in parentheses. Day of disease onset and maximum clinical scores for each mouse are shown for two experiments. (D,E) Splenocytes from naïve Il3+/+ and Il3−/− TCR Tg mice were activated with MBP Ac1-11 peptide under encephalitogenic Th1 and Th17 conditions for 3 days. (D) Th1 cells and (E) Th17 cells were collected and adoptively transferred into B10.PL mice (5 × 106 cells/mouse). EAE clinical scores were monitored daily (mean ± SEM). Day of disease onset and maximum clinical scores for each mouse are shown for all replicate experiments. (F–H) Splenocytes from naïve MBP-specific TCR Tg mice were activated with MBP Ac1-11 peptide under encephalitogenic Th1 and Th17 conditions in the presence of anti-IL-3 or isotype Ab for 3 days. (F) Supernatants were analyzed by ELISA for IFNγ, IL-17A, and GM-CSF. (G) Th1 cells and (H) Th17 cells were collected and adoptively transferred into naive B10.PL mice (5 × 106 cells per mouse).

To determine if IL-3 deficiency protects mice from EAE development, B10.PL IL-3+/+, IL-3+/−, and IL-3−/− mice were immunized with MBP Ac1-11/CFA. The incidence, day of onset, disease course, and maximum clinical course were not significantly different between the groups (Figure 2C). To specifically address the role of IL-3 in CD4 T cells, myelin-specific IL-3+/+ and IL-3−/− T cells were differentiated into encephalitogenic Th1 and Th17 cells and transferred into B10.PL mice. The incidence of disease, day of onset, and maximum clinical score were not significantly different between the mice that received the IL-3+/+ and IL-3−/− T cells (Figures 2D,E). There was also no difference in disease course between IL-3+/+ and IL-3−/− Th1 cells (Figure 2D). There was a slight decrease in disease course in the IL-3−/− Th17 cells (Figure 2E), but this was not reproducible.

To validate these data, myelin-specific CD4 T cells were cultured with a neutralizing IL-3 antibody during the in vitro differentiation into encephalitogenic Th1 and Th17 cells. Although there was a complete abrogation of IL-3 with the antibody (data not shown), there was no change in IFNγ, IL-17, or GM-CSF expression (Figure 2F). There was also no reduction in the encephalitogenicity of myelin-specific Th1 or Th17 cells with IL-3 neutralization (Figures 2G,H), indicating that IL-3 was not essential for the generation of encephalitogenic T cells. These data suggest that IL-3 levels are associated with the encephalitogenic capacity of myelin-specific Th1 and Th17 cells, but IL-3 plays no major role in the encephalitogenic capacity of the cells.

Discussion

As the role of IL-3 in MS is not well-described, the goal of this study was to determine if myelin-specific IL-3 T cell production was necessary for encephalitogenicity. IL-3 expression was significantly higher on encephalitogenic T cells, but loss of IL-3 in T cells had no significant effect on the development or severity of EAE. Previous studies have demonstrated that IL-3 is highly expressed in encephalitogenic cells (16, 25, 26), consistent with the data from this study. However, the high expression of IL-3 in combination with the high expression of GM-CSF, a cytokine located in the same gene cluster, indicates that the upregulation of these two genes may be a product of increased upstream promotor function and not as a causative factor in encephalitogenicity. Renner et al. (16) have shown results contradictory to the findings in this study, which may be due to differences in experimental design. Their study found a modest reduction in B6/MOG EAE severity at days 18–20 using a parametric t-test, instead of analyzing EAE using a non-parametric test since the EAE scoring system is not linear. Their study also found that EAE was more severe in IL-3−/− mice than IL-3+/− mice, which is inconsistent with their conclusion. However, they did observe that administration of IL-3 in vivo enhanced EAE severity and administration of anti-IL3 modestly lessened disease severity, indicating that IL-3 may contribute to pathology.

IL-3 has been implicated as both a pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine. IL-3 has been shown to not only contribute to microglia activation (35) but also protect neurons from inflammation following mechanical strain (36). IL-3 transcripts have been shown to be upregulated in CNS lesions of MS patients (37), and chronic expression of IL-3 by astrocytes results in an MS-like disease in mice (38). In the present study, we differentiated the effects of systemic loss of IL-3 compared to T cell-specific loss of IL-3 and found that IL-3 was not a major contributor to the incidence or severity of EAE. The observations that IL-3 is expressed in encephalitogenic T cells and myelin-specific memory T cells from MS patients (27) indicate that IL-3 may be a marker of encephalitogenic T cells, possibly due to transcriptional upregulation of the Il3/Csf2 gene cluster, but an unlikely therapeutic target.

Ethics Statement

The protocols used for these experiments received prior approval by the OSU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were conducted in accordance with the United States Public Health Service’s Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Author Contributions

PL and MX designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and assisted with writing the manuscript. WP assisted with the in vivo experiments. YY and AL-R designed experiments, analyzed data, and prepared the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The IL-3-deficient mice were developed by Glenn Dranoff (Dana Farber Cancer Institute) and provided to us by Booki Min (Cleveland Clinic). This study was funded by grants to AL-R from the NIH (1 R01 NS067441) and National Multiple Sclerosis Society (RG 3812). PL was supported by award TL1TR000091 from Clinical Translational Science Award, funded by NIH.

References

- 1.Frohman EM, Racke MK, Raine CS. Multiple sclerosis – the plaque and its pathogenesis. N Engl J Med (2006) 354(9):942–55. 10.1056/NEJMra052130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allegretta M, Nicklas JA, Sriram S, Albertini RJ. T cells responsive to myelin basic protein in patients with multiple sclerosis. Science (1990) 247(4943):718–21. 10.1126/science.1689076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lovett-Racke AE, Trotter JL, Lauber J, Perrin PJ, June CH, Racke MK. Decreased dependence of myelin basic protein-reactive T cells on CD28-mediated costimulation in multiple sclerosis patients: a marker of activation/memory T cells. J Clin Invest (1998) 101(4):725–30. 10.1172/JCI1528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burns J, Bartholomew B, Lobo S. Isolation of myelin basic protein-specific T cells predominantly from the memory T-cell compartment in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol (1999) 45(1):33–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dotsika EN, Sanderson CJ. Interleukin-3 production as a sensitive measure of T-lymphocyte activation in the mouse. Immunology (1987) 62(4):665–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lantz CS, Boesiger J, Song CH, Mach N, Kobayashi T, Mulligan RC, et al. Role for interleukin-3 in mast-cell and basophil development and in immunity to parasites. Nature (1998) 392(6671):90–3. 10.1038/32190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Denzel A, Maus UA, Rodriguez Gomez M, Moll C, Niedermeier M, Winter C, et al. Basophils enhance immunological memory responses. Nat Immunol (2008) 9(7):733–42. 10.1038/ni.1621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palacios R, Garland J. Distinct mechanisms may account for the growth-promoting activity of interleukin 3 on cells of lymphoid and myeloid origin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1984) 81(4):1208–11. 10.1073/pnas.81.4.1208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palacios R, Henson G, Steinmetz M, McKearn JP. Interleukin-3 supports growth of mouse pre-B-cell clones in vitro. Nature (1984) 309(5964):126–31. 10.1038/309126a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuribara R, Kinoshita T, Miyajima A, Shinjyo T, Yoshihara T, Inukai T, et al. Two distinct interleukin-3-mediated signal pathways, Ras-NFIL3 (E4BP4) and Bcl-xL, regulate the survival of murine pro-B lymphocytes. Mol Cell Biol (1999) 19(4):2754–62. 10.1128/MCB.19.4.2754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Storozynsky E, Woodward JG, Frelinger JG, Lord EM. Interleukin-3 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor enhance the generation and function of dendritic cells. Immunology (1999) 97(1):138–49. 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00741.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elliott MJ, Vadas MA, Cleland LG, Gamble JR, Lopez AF. IL-3 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor stimulate two distinct phases of adhesion in human monocytes. J Immunol (1990) 145(1):167–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Didichenko SA, Spiegl N, Brunner T, Dahinden CA. IL-3 induces a Pim1-dependent antiapoptotic pathway in primary human basophils. Blood (2008) 112(10):3949–58. 10.1182/blood-2008-04-149419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weber GF, Chousterman BG, He S, Fenn AM, Nairz M, Anzai A, et al. Interleukin-3 amplifies acute inflammation and is a potential therapeutic target in sepsis. Science (2015) 347(6227):1260–5. 10.1126/science.aaa4268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brühl H, Cihak J, Niedermeier M, Denzel A, Rodriguez Gomez M, Talke Y, et al. Important role of interleukin-3 in the early phase of collagen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum (2009) 60(5):1352–61. 10.1002/art.24441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Renner K, Hellerbrand S, Hermann F, Riedhammer C, Talke Y, Schiechl G, et al. IL-3 promotes the development of experimental autoimmune encephalitis. JCI Insight (2016) 1(16):e87157. 10.1172/jci.insight.87157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McQualter JL, Darwiche R, Ewing C, Onuki M, Kay TW, Hamilton JA, et al. Granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor: a new putative therapeutic target in multiple sclerosis. J Exp Med (2001) 194:873–82. 10.1084/jem.194.7.873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bettelli E, Sullivan B, Szabo SJ, Sobel RA, Glimcher LH, Kuchroo VK. Loss of T-bet, but not STAT1, prevents the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med (2004) 200(1):79–87. 10.1084/jem.20031819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lovett-Racke AE, Rocchini AE, Choy J, Northrop SC, Hussain RZ, Ratts RB, et al. Silencing T-bet defines a critical role in the differentiation of autoreactive T lymphocytes. Immunity (2004) 21(5):719–31. 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gocke AR, Northrop SC, Ben L, Hussain RZ, Cravens PD, Racke MK, et al. T-bet regulates the fate of TH1 and TH17 lymphocytes in autoimmunity. J Immunol (2007) 178(3):1341–8. 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ponomarev ED, Shriver LP, Maresz K, Pedras-Vasconcelos J, Verthelyi D, Dittel BN. GM-CSF production by autoreactive T cells is required for the activation of microglial cells and the onset of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol (2007) 178:39–48. 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang Y, Weiner J, Liu Y, Smith AJ, Huss DJ, Winger R, et al. T-bet is essential for encephalitogenicity of both Th1 and Th17 cells. J Exp Med (2009) 206(7):1549–64. 10.1084/jem.20082584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Codarri L, Gyülvészi G, Tosevski V, Hesske L, Fontana A, Magnenat L, et al. RORγt drives production of the cytokine GM-CSF in helper T cells, which is essential for the effector phase of autoimmune neuroinflammation. Nat Immunol (2011) 12:560–7. 10.1038/ni.2027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El-Behi M, Ciric B, Dai H, Yan Y, Cullimore M, Safavi F, et al. The encephalitogenicity of T(H)17 cells is dependent on IL-1- and IL-23-induced production of the cytokine GM-CSF. Nat Immunol (2011) 12:568–75. 10.1038/ni.2031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hofstetter HH, Karulin AY, Forsthuber TG, Ott PA, Tary-Lehmann M, Lehmann PV. The cytokine signature of MOG-specific CD4 cells in the EAE of C57BL/6 mice. J Neuroimmunol (2005) 170(1–2):105–14. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee Y, Awasthi A, Yosef N, Quintana FJ, Xiao S, Peters A, et al. Induction and molecular signature of pathogenic TH17 cells. Nat Immunol (2012) 13(10):991–9. 10.1038/ni.2416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao Y, Goods BA, Raddassi K, Nepom GT, Kwok WW, Love JC, et al. Functional inflammatory profiles distinguish myelin-specific T cells from patients with multiple sclerosis. Sci Transl Med (2015) 7(287):287ra74. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa8038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee PW, Smith AJ, Yang Y, Selhorst AJ, Liu Y, Racke MK, et al. IL-23R-activated STAT3/STAT4 is essential for Th1/Th17-mediated CNS autoimmunity. JCI Insight (2017) 2. 10.1172/jci.insight.91663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mach N, Lantz CS, Galli SJ, Reznikoff G, Mihm M, Small C, et al. Involvement of interleukin-3 in delayed-type hypersensitivity. Blood (1998) 91:778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goverman J, Woods A, Larson L, Weiner LP, Hood L, Zaller DM. Transgenic mice that express a myelin basic protein-specific T cell receptor develop spontaneous autoimmunity. Cell (1993) 72:551–60. 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90074-Z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Connor RA, Prendergast CT, Sabatos CA, Lau CW, Leech MD, Wraith DC, et al. Th1 cells facilitate the entry of Th17 cells to the central nervous system during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol (2008) 181(6):3750–4. 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.3750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Das J, Ren G, Zhang L, Roberts AI, Zhao X, Bothwell ALM, et al. Transforming growth factor beta is dispensable for the molecular orchestration of Th17 cell differentiation. J Exp Med (2009) 206:2407–16. 10.1084/jem.20082286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghoreschi K, Laurence A, Yang XP, Tato CM, McGeachy MJ, Konkel JE, et al. Generation of pathogenic Th17 cells in the absence of TGF-β signaling. Nature (2010) 467(7318):967–71. 10.1038/nature09447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee PW, Yang Y, Racke MK, Lovett-Racke AE. Analysis of TGF-β1 and TGF-β3 as regulators of encephalitogenic Th17 cells: implications for multiple sclerosis. Brain Behav Immun (2015) 46:44–9. 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Natarajan C, Sriram S, Muthian G, Bright JJ. Signaling through JAK2-STAT5 pathway is essential for IL-3-induced activation of microglia. Glia (2004) 45(2):188–96. 10.1002/glia.10316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lim JC, Lu W, Beckel JM, Mitchell CH. Neuronal release of cytokine IL-3 triggered by mechanosensitive autostimulation of the P2X7 receptor is neuroprotective. Front Cell Neurosci (2016) 10:270. 10.3389/fncel.2016.00270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baranzini SE, Elfstrom C, Chang SY, Butunoi C, Murray R, Higuchi R, et al. Transcriptional analysis of multiple sclerosis brain lesions reveals a complex pattern of cytokine expression. J Immunol (2000) 165(11):6576–82. 10.4049/jimmunol.165.11.6576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chiang CS, Powell HC, Gold LH, Samimi A, Campbell IL. Macrophage/microglial-mediated primary demyelination and motor disease induced by the central nervous system production of interleukin-3 in transgenic mice. J Clin Invest (1996) 97(6):1512–24. 10.1172/JCI118574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]