Abstract

Background

Total joint arthroplasty (TJA) remains the highest expenditure in the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) budget. One model to control cost is the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) model. There has been no published literature to date examining the efficacy of CJR on value-based outcomes. The purpose of this study was to determine the efficacy and sustainability of a multidisciplinary care redesign for total joint arthroplasty under the CJR paradigm at an academic tertiary care center.

Methods

We implemented a system-wide care redesign, affecting all patients who underwent a total hip or total knee arthroplasty at our academic medical center. The main study outcomes were cost (to CMS), discharge destination, complications and readmissions, and length of stay (LOS); these were measured using the 2017 initial CJR reconciliation report, as well as our institutional database.

Results

The study included 1536 patients (41% Medicare). Per-episode cost to CMS declined by 19.5% to 11% below the CMS-designated national target. Home discharge increased from 62% to 87%. CMS readmissions declined from 15% to 6%; major complications decreased from 2.3% to 1.9%; and LOS declined from 3.6 to 2.1 days.

Conclusions

A mandatory episode-based bundled-payment program can induce favorable changes to value-based metrics, improving quality and outcomes for health-care consumers. Quality and value were improved in this study, evidenced by lower 90-day episode cost, more home discharges, lower readmissions and complications, and shorter LOS. This approach has implications not just for CMS, but for private payers, corporate health programs, and fixed-budget health-care models.

Keywords: Comprehensive care for Joint Replacement (CJR) model, Total hip and knee arthroplasty, Care pathway redesign, Value-based care

Introduction

Lower extremity joint replacement of the hip and knee remain among the most common and most cost-effective procedures performed in the United States, together representing the single highest line item in the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) annual expenditure budget [1], [2]. There has been interest in finding ways to control cost to CMS associated with total joint arthroplasty (TJA), while maintaining access for beneficiaries to these life-changing interventions.

The CMS is in the midst of transitioning from being a volume-based buyer to a value-based buyer and is now emphasizing payment models that deviate from the traditional fee-for-service model, to control cost, reward favorable outcomes, and improve value in care [3]. The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 codified a new CMS payment plan: the Advanced Alternative Payment Model [4]. The first Advanced Alternative Payment Model to gain substantial traction in the orthopaedic community was the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI), a voluntary participation model rewarding physicians with gainsharing for favorable outcomes and diminished costs [5]. Bundled-payment models attempt to unify disparate providers to better coordinate care, avoid unnecessary treatments, and improve outcomes by sharing a single episode “target price” for a specific episode of care. Recent literature has supported that BPCI programs for TJA lead to both lowered costs and improved value for CMS [5], [6].

In April 2016, CMS implemented the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) model, which brought the bundling initiative mandatorily (unlike BPCI, which remains voluntary) to a group of 67 metropolitan statistical areas [7]. Our health system was notified in July 2015 that we had been included in the initial phase of the CJR.

Preliminary data suggested that our health system's average 90-day episode cost would be 4.8% above the national target price. In light of this, we initiated a comprehensive effort, led primarily by the arthroplasty division, to examine the care pathway and determine opportunities for improvement. Our primary concern was to improve the value of our care delivery, by maintaining a high standard of patient safety and quality in outcomes while diminishing the cost of the episode of care, both to payers (CMS in particular) and the health system. Moreover, we questioned whether such a care redesign was sustainable, scalable, and applicable across a diverse payer mix.

The primary outcome measures we used to answer this question were 90-day cost to CMS, direct cost to the hospital, percent disposition to home vs a postacute care setting (skilled nursing facility [SNF] or inpatient rehab facility), complications (using the CJR final rule), all-cause readmissions, and length of stay (LOS).

Material and methods

Our institution is an 852-bed tertiary care academic medical center serving as the primary referral center for 18 counties and secondary major referral center to another 15; it is a level 1 trauma center that functions as a safety-net hospital, and as such caters to a diverse group of patients with both medical complexity and socioeconomic diversity. In addition, ours is a teaching hospital where resident and fellow education is an important commitment. Owing to the size of the institution, the number of diverse clinical programs, the wide geographic catchment area, and complexity of referred patients, wholesale or sustained change in clinical pathways is typically challenging.

We created a multidisciplinary task force that met monthly to examine the care process, through a patient- and family-centered care model as described by DiGioia et al. [8]. Our overall goal was to manage the entire episode of care, from the initial outpatient consultation, through the surgical encounter, to long-term function and outcomes. Table 1 summarizes the key areas that were redesigned with a patient-centered and outcome-based approach.

Table 1.

Redesign of the total joint replacement episode.

| Task force constituents: orthopaedic surgery, anesthesiology, case management, rehabilitation services, home care companies, hospital administration, nursing leaders (orthopaedic unit, preoperative, operating room, and postoperative), and hospital quality and data personnel |

|---|

| Preoperative |

| Creation of a Patient Selection Tool: recognize and control known modifiable risk factors, that is, cigarette smoking, chronic narcotic use, morbid obesity, poorly controlled diabetes |

| Patient Medical Optimization: literature-guided three-tiered system (red-yellow-green) using systems-based classification, attempt to move patients to green across all categories; exercise caution when yellow (attempts made to modify, taken on case-by-case basis); red is a hard stop (do not proceed with surgery) |

| Use of Risk Assessment and Prediction Tool (RAPT) for predicting postacute placement: score >9, plan for home discharge; score 6-9, invest preop resources to optimize possibility of home discharge; score <6, plan for postacute care facility |

| Physical Optimization (“prehabilitation” for deconditioning) |

| Chlorhexidine (skin) and Mupirocin (nasal) decolonization |

| Narcotic Protocol, stratified by patient narcotic exposure (narcotic naive, standard, or chronic narcotic user) |

| Engagement of patients by Case Management before admission |

| Documentation of a firm postacute plan before admission (home is default) |

| High-Risk Anesthesia Pathwaya: patients with 2 or more poorly controlled cardiopulmonary disease conditions referred to preoperative “high-risk” clinic to discuss risk and optimization with a high-risk anesthesia provider |

| Joint Replacement Education Programa |

| Acute Care |

| Acute Care pathway changed from 4 days to 2 days |

| Physical therapy started on the day of surgery and twice daily until discharge |

| Use of a physical therapy gym on the orthopaedic unit |

| Preoperative disposition plan is not changed without consulting surgeon |

| Predominant use of regional-only anesthesia (spinal anesthesia with preop regional block, ± home catheter when indicated) |

| Multimodal pain management: acetaminophen, celecoxib, tramadol ± neuromodulating agent |

| No routine Foley catheter use |

| Simplified wound dressings and no routine dressing changes |

| Case management engagement within 12 hours of surgery |

| Discharge teaching by nursing starting on postoperative day 1 |

| Uniform messaging across all services for safe, early home discharge |

| Postacute Care |

| Improved patient engagement and tracking by orthopaedic team via a telephone |

| Preferred Skilled Nursing Facilities and Home care companies with regular communication |

| 7 days per week access to Orthopaedic After Hours Clinic instead of emergency room |

| Nurse navigatora |

| Patient engagement and tracking electronic platforma |

This component of the redesign was not active during the study period.

One major goal of the preoperative redesign was to improve patient selection and optimization and not to avoid care for riskier patients (a practice known as “cherry-picking or lemon-dropping,” a common concern with other bundled-payment initiatives) but to improve their modifiable risk factors through comanagement/consultation services. Education was another major goal: transforming the culture across the care continuum to expect early mobility and safe, early discharge to home. Prior to redesign, a clear postdischarge plan was often lacking, resulting in prolonged LOS and a determination for use of a SNF based on early function after surgery rather than baseline function.

During the acute care period, extensive attention was directed toward emphasizing regional anesthesia, early mobilization, early recovery, and safe discharge to home. All medical staff interacting with the patient were coordinated to emphasize the previously mentioned expectations. We conceded to accept modest increases in LOS to reach home rather than SNF discharge, if for instance a patient was felt to benefit from an additional day of inpatient stay to improve home safety.

For the postacute period, enhanced patient engagement and tracking was implemented. Patients were called proactively at regular intervals and encouraged to call the orthopaedic practice readily with concerns, to reduce emergency room (ER) visits for routine issues. We leveraged our department's 7-day orthopaedic walk-in clinic to allow patients with concerns to be seen promptly by someone from our department, reserving the ER for medical emergencies only. Home care companies and postacute facilities were also contacted by our team and encouraged to call our practice first with any concerns.

We first implemented a 3-month pilot program with 2 of the surgeons (C.F.G. and H.K.P.) to see the scalability of our planned changes. The program was then implemented across the enterprise on February 1, 2016, to allow a 2-month run-in prior to the start date for the CJR. As such, we reviewed patient data from February 1, 2016 through January 31, 2017, a period of 1 year. This was compared to the 1 year leading up to the initiation of the pilot program, from November 1, 2014 to October 31, 2015.

The initial institutional 1-year CJR program reconciliation was used to obtain CMS cost data and readmission data. The year 1 data set included full 90-day episode of care data for the first 3 quarters of the program year (to allow a full 90-day runout following each episode). Data were reviewed and analyzed for all patients undergoing primary, unilateral total hip and total knee arthroplasty (all patients in Medicare Severity-Diagnosis Related Groups 469 and 470, the Medicare classification system used to set a fixed reimbursement for care of like patients with like problems—in this case unilateral primary total hip or knee arthroplasty) at our institution. CJR data were augmented by institutional data. Fracture cases were excluded, as multiple studies have shown these patients to differ from elective arthroplasty cases [9], [10].

Institutional data were obtained through use of the Business Objects/SAP suite of software (BusinessObjects XI, San Jose, CA), which obtains data in blinded nature from the electronic medical record. As such, the study was exempt from the institutional review board approval.

Results

Results are summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Demographic information comparing the baseline period to the redesign period.

| Baseline | Study period | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 696 | 840 |

| Medicare | 288 (41%) | 348 (41%) |

| Non-Medicare | 408 (59%) | 492 (59%) |

| Average body mass index | 32.1 | 31.7 |

| Medicare | 31.7 | 31.3 |

| Non-Medicare | 32.4 | 32.0 |

| Average age (y) | 62 | 62 |

| Medicare | 69 | 69 |

| Non-Medicare | 58 | 58 |

| Average Charlson Comorbidity Index | 2.24 | 2.27 |

| Medicare | 2.04 | 2.4 |

| Non-Medicare | 2.38 | 2.18 |

Table 3.

Outcomes data comparing the baseline and redesign period.

| Baseline | Study period | BPCI [6] | NMS [11] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 696 | 840 | 721→785 | 601,000 |

| Medicare | 288 (41%) | 348 (41%) | 721→785 | 601,000 |

| Non-Medicare | 408 (59%) | 492 (59%) | – | – |

| Length of stay (d) | 3.58 | 2.11 | – | – |

| Medicare | 3.67 | 2.10 | 3.6→3.0 | – |

| Non-Medicare | 3.54 | 2.13 | – | – |

| Rate of discharge to postacute facility | 38.0% | 13.4% | – | – |

| Medicare | 42.2% | 18.1% | 44%→28% | 39.9% (TKA) 40.1% (THA) |

| Non-Medicare | 23.4% | 9.9% | – | – |

| Readmission rate | 4.9% | 3.9% | – | – |

| Medicare | 4.9% | 5.2% | 13%→8% | 6.3% (TKA) 7% (THA) |

| Non-Medicare | 4.9% | 3.0% | – | – |

| Medicare reconciliationa | – | 6.0% | – | – |

| Cost change from baseline | ||||

| Direct (hospital) | – | −27% | – | – |

| Cost to CMS (vs target) | +4.8% (vs national average price) | −11%b (vs national target price) | −20% (vs institutional baseline) | – |

NMS, national Medicare sample; TKA, total knee arthroplasty; THA, total hip arthroplasty.

In addition, a comparison of findings in the present study with those of a BPCI and a 2013-14 NMS.

Includes hip fracture patients (excluded from the remainder of the study).

From 2017 CJR reconciliation.

Volume

The initial baseline period consisted of 696 patients, of which 288 were Medicare patients (41%). The study period comprised 840 patients (an increase of 21%), with 348 (41%) patients being CJR eligible.

Demographics

The patient population remained unchanged throughout the redesign. The average age in all groups (preredesign and postredesign) was 62 years. The average body mass index increased from 31.3 to 31.7. The average Charlson Comorbidity Index in our Medicare patients increased from 2.04 to 2.40 from the baseline to the study period.

Cost

Based on initial CJR reconciliation data, the cost to CMS declined by 19.5% compared to baseline, to 11.0% below the target price. Direct per-episode hospital cost declined by 27.3% after the care redesign.

Complications

CJR-specific complications, including acute myocardial infarction, pneumonia, sepsis, venous thromboembolic disease, surgical bleed, periprosthetic joint infection, and device-related mechanical complication, occurred in 2.3% of patients in the baseline period and in 1.9% of patients following the redesign.

Readmissions

All-cause readmissions to our institution were 4.9% during the year baseline period (for all patients). This number declined to 3.9% in the 1 year following the redesign, though with a slight increase in the Medicare-only population (from 4.9% to 5.1%). According to the CMS CJR reconciliation, our readmission rate for all eligible Diagnosis Related Groups 469 and 470 cases (which includes hip fractures) declined from 15% to 6%. Hip fractures were excluded from our institutional data, making the CMS figure a worst-case readmission rate for the Medicare segment.

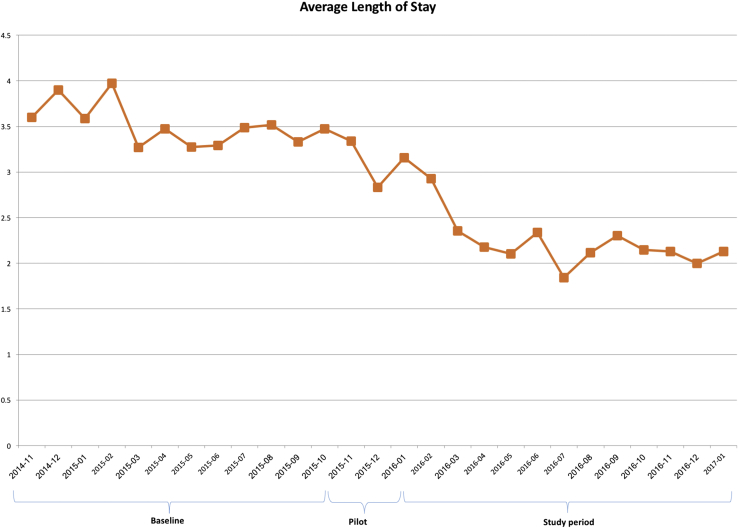

Length of stay

LOS decreased from 3.6 days at the baseline to 2.1 days over the study period, a reduction of 1.5 days. In the Medicare subset, this change was from 3.7 to 2.1 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Average length of stay, by month, during the study period. The initial 12-month baseline period, the pilot period of 3 months, and the study period are identified.

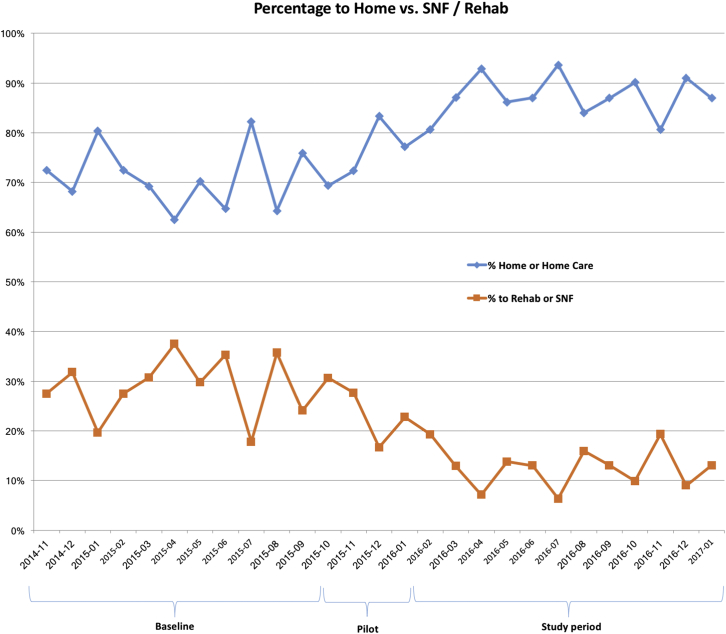

Discharge destination

In the baseline period, 62% of patients were being discharged to home. In the Medicare population, this was only 58%. During the study period, 87% of patients were discharged to home, with 82% of Medicare patients reaching this discharge goal (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Discharge disposition by location. The baseline, pilot, and study period are identified. SNF, skilled nursing facility.

Discussion

When faced with a mandatory pending change in reimbursement model, we sought to create an efficient, high-quality care model across our TJA service line. We demonstrated a sustained improvement in efficiency of care delivery to all TJA patients despite increasing volume, while keeping patient demographics unchanged, thus avoiding concerns for “cherry-picking” or “lemon-dropping.” Though the impetus for this change was a CMS initiative, these changes were demonstrated for all patients regardless of payer class. This improved value (reflected in lower cost, decreased readmissions and complications, decreased LOS, and less discharge to postacute facilities) was confirmed in the initial CJR program reconciliation report.

The CJR attempts to control cost by shifting to a value-based purchasing approach, emphasizing both outcomes and cost-efficacy. Our approach, therefore, was to focus on initiatives that we felt inherently provided value for patients, not just cost savings. All aspects of the redesign (featured in Table 1) fit into one of 5 categories: (1) creation of a multidisciplinary care pathway with oversight over all components of the entire 90-day care episode; (2) preoperative patient optimization through comanagement and unified risk stratification; (3) improved preoperative education of the patient, their family, and the care team; (4) implementation of a rapid recovery pathway with regional anesthesia and early mobility; and (5) investment of resources in preoperative discharge planning and postdischarge patient tracking.

Often, facets of the redesign involved increased upfront spend on the care team side to improve postoperative spend on the payer side. Utilization of postacute care service is a primary driver of increased cost to CMS [12] and is a main target of most cost-saving measures. Moreover, discharge to home is associated with improved recovery, less likelihood of readmission, and a lower overall complication rate, even when controlling for comorbidities and social factors [13], [14], [15]. In the US, however, the utilization in the Medicare population of postacute facilities remains high. A recent sampling of the National Medicare sample, reviewing over 600,000 TJA episodes, showed utilization rates of around 40% in 2013-2014 [11]. Achieving numbers well below this rate represents a real opportunity for cost savings and improved quality. Thus, we emphasized to patients the importance of finding a “champion” who would assist them through the episode of care and commit to helping them recover postoperatively at home. Achieving this measure was worth extra resource investment in clinic.

Other American TJA centers have recently published data on their experience with care redesign under bundled initiatives. Notably, Dundon et al. [6] recently demonstrated significant improvement in value-based metrics at their tertiary referral center. Their study, however, focused on Medicare patients only and was done under the paradigm of a BPCI program, which has different risks and rewards. A strength, and novel finding, of the present study is demonstration of improvements not only in Medicare patients but also in all patients regardless of the payer, making it applicable across any total joint patient population. Thus, the cost savings we demonstrated to CMS we expect to apply to private payers as well.

One notable distinction between CJR and BPCI is its mandatory nature. High-performing centers with invested physician teams may choose to “opt-in” to BPCI, reaping financial savings through a cost-efficient performance, besting their historical averages, and sharing in resultant savings. CJR, by contrast, is mandatory for all hospitals taking Medicare payments in the 67 included metropolitan statistical areas. Success is determined under the CJR paradigm by comparison with national and regional target pricing, in a zero-sum game format, with an equal number of “winners” and “losers.” Thus, a blueprint for success that is both cost- and time-effective to implement, and value based, is in high demand. This study also demonstrates that it is not necessary to “cherry-pick” to be successful in this payment paradigm.

Readmissions are another substantial cost driver [16], [17]. National readmission rates hover around 7% in all Medicare beneficiaries [11], though this number may be expected to be higher at safety-net hospitals and tertiary referral centers. In the present study, the CJR reconciliation data, received after year 1 of the program, showed a 6% readmission rate, a decline from 15% in the baseline Medicare comparison group (including hip fracture patients). By comparison, our institutional readmissions declined from 4.9% to 3.9%. These comparisons are summarized in Table 3.

Our model, featuring an engaged primary service, is a practical and efficient one. There is no gainsharing model in place at our hospital (though the CJR program does allow and encourage gainsharing). These profit-sharing models can be used to increase physician buy-in but may pose ethical questions for the involved physicians [18]. Rather, we relied on surgeon competition and a desire for improved patient outcomes. We were provided with real-time (within 4-6 weeks) surgeon-specific data on LOS, as well as discharge disposition, which allowed each surgeon to track their success over time. This transparency and data access provided impetus for month-to-month improvements.

We also found the multidisciplinary approach to be essential. At our regular meetings, we had input and opportunity to exchange ideas with the teams who had regular patient interactions. This led to an evolving and dynamic interchange with constant improvements.

Changes that were implemented early in the redesign continued to display results even 1-year in, with continued iterative improvements. Our physical therapists now work toward a goal of home discharge on day 1 and contact the providers when a patient will likely not meet this goal. Prior to the redesign, all therapists worked toward a goal of discharge readiness at postoperative day 3, and there was a high expectation of discharge to a postacute care facility. This shift in expectation and goals was transformative across the service line. A majority of our patients have a short-stay admission (1 night), and an outpatient total joint pathway has resulted directly from this. In addition, ongoing collaboration with our anesthesia colleagues through this redesign has resulted in predominant use of regional-only anesthesia and even opioid-free pathways.

There are numerous ongoing challenges, especially for Medicare patients. Because Medicare benefits for SNF are well known, many patients choose a preselected facility before their initial office visit. This decision is very difficult to reverse no matter how well they do after surgery. In addition, despite ongoing efforts, some patients utilize the ER for even routine postoperative issues, often resulting in unnecessary readmission; the same occasionally still happens with local home care companies and SNFs.

Some components that we designated early in the process as essential were not yet in action at the time of data collection. We have now implemented a joint replacement education program, which other programs have demonstrated improves TJA quality metrics [19]. We also successfully implemented a high-risk anesthesia pathway only recently, so further improvements in our data may be anticipated [20].

Our study has some limitations. First, data for payers other than CMS were obtained through our care episode database, which limits us to retrospective review of trends, and also lacks the ability to capture readmissions or complications that presented at other institutions. However, as the tertiary center for the large surrounding area, and owing to our close tracking of patients postoperatively, we anticipate this number to have a small impact.

The initial CJR reconciliation made available from CMS allows an estimation of true costing. Of note, the redesign showed benefit to all patients, regardless of age or payer status, in our institutional data, paralleling the CMS data. Payers other than CMS have been increasing utilization of alternative payment models. We anticipate these savings would be applicable to private payers, corporate health programs, and fixed-budget payment systems, based on improved readmissions and metrics related to discharge disposition. Moreover, interest in bundled-payment programs continues to grow, with a possibility for further mandatory CMS programs affecting physicians involved in multiple facets of medical care beyond TJA [21], [22]. A usable blueprint for implementation will certainly be of interest.

An additional concern may be the improved competition as CJR matures. Initial target prices are based on institutional historical data and national data, transitioning with time to more regional data. As our institution and other centers improve, beating target prices will become progressively more challenging (this, of course, is the entire point of a mandatory bundled-payment program—to drive iterative improvements by increasing competition and transparency). However, we feel that improved quality will continue to provide real value for our patients regardless of the payer model or the economics of competing institutions.

We cautiously report CJR reconciliation data as this figure is expected to change with time. CJR utilizes a prospective target price affected over years by performance of national and regional peers. Despite extensive redesign by an invested group of surgeons and institution, and promising trends in our institutional data, by the nature of the CJR design and the inherent lag in claims data, we will be unable to judge our true progress from the perspective of CMS for several years. True episode costs remain challenging to both monitor and control in real time, especially considering the size and scope of CMS.

Conclusions

The CJR has added new considerations for all parties involved in providing care to TJA patients. It is possible for academic, safety-net multispecialty tertiary health centers with a burden of complex patients to continue to provide safe, effective, value-oriented care that may meet efficiency standards for CMS reimbursement. A multidisciplinary approach is essential, with full surgeon and hospital investment and with a patient-centered focus as care pathways are examined and redesigned. Real-time data acquisition and interpretation remains essential, though challenging.

Footnotes

One or more of the authors of this paper have disclosed potential or pertinent conflicts of interest, which may include receipt of payment, either direct or indirect, institutional support, or association with an entity in the biomedical field which may be perceived to have potential conflict of interest with this work. For full disclosure statements refer to https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artd.2018.02.002.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Cram P., Lu X., Kates S.L., Singh J.A., Li Y., Wolf B.R. Total knee arthroplasty volume, utilization, and outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries, 1991-2010. JAMA. 2012;308(12):1227. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurtz S., Ong K., Lau E., Mowat F., Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bozic K.J., Ward L., Vail T.P., Maze M. Bundled payments in total joint arthroplasty: targeting opportunities for quality improvement and cost reduction. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(1):188. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3034-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saleh K.J., Shaffer W.O. Understanding value-based reimbursement models and trends in orthopaedic health policy: an introduction to the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) of 2015. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2016;24(11):e136. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-16-00283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iorio R., Clair A.J., Inneh I.A., Slover J.D., Bosco J.A., Zuckerman J.D. Early results of Medicare's bundled payment initiative for a 90-day total joint arthroplasty episode of care. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(2):343. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dundon J.M., Bosco J., Slover J., Yu S., Sayeed Y., Iorio R. Improvement in total joint replacement quality metrics: year one versus year three of the bundled payments for care improvement initiative. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(23):1949. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.16.00523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model. Secondary Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model 2016. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/cjr [accessed 05.05.17]

- 8.DiGioia A.M., 3rd, Fann M.N., Lou F., Greenhouse P.K. Integrating patient- and family-centered care with health policy: four proposed policy approaches. Qual Manag Health Care. 2013;22(2):137. doi: 10.1097/QMH.0b013e31828bc2ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le Manach Y., Collins G., Bhandari M. Outcomes after hip fracture surgery compared with elective total hip replacement. JAMA. 2015;314(11):1159. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoon R.S., Mahure S.A., Hutzler L.H., Iorio R., Bosco J.A. Hip arthroplasty for fracture vs elective care: one bundle does not fit all. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(8):2353. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Middleton A., Lin Y.-L., Graham J.E., Ottenbacher K.J. Outcomes over 90-day episodes of care in Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries receiving joint replacement. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(9):2639. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newhouse J.P., Garber A.M. Geographic variation in Medicare services. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(16):1465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1302981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keswani A., Tasi M.C., Fields A., Lovy A.J., Moucha C.S., Bozic K.J. Discharge destination after total joint arthroplasty: an analysis of postdischarge outcomes, placement risk factors, and recent trends. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(6):1155. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLawhorn A.S., Fu M.C., Schairer W.W., Sculco P.K., MacLean C.H., Padgett D.E. Continued inpatient care after primary total knee arthroplasty increases 30-day post-discharge complications: a propensity score-adjusted analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(9S):S113. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fu M.C., Samuel A.M., Sculco P.K., MacLean C.H., Padgett D.E., McLawhorn A.S. Discharge to inpatient facilities after total hip arthroplasty is associated with increased post-discharge morbidity. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(9S):S144. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clement R.C., Gray C.M., Kheir M.M. Will Medicare readmission penalties motivate hospitals to reduce arthroplasty readmissions? J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(3):709. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clement R.C., Derman P.B., Graham D.S. Risk factors, causes, and the economic implications of unplanned readmissions following total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(8 Suppl):7. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mercuri J.J., Iorio R., Zuckerman J.D., Bosco J.A. Ethics of total joint arthroplasty gainsharing. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(5):e22. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.16.00594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes M.M., Gordon Newbern D., Lowry Barnes C. Volume and length of stay in a total joint replacement program. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2009;18(4):195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu S., Garvin K.L., Healy W.L., Pellegrini V.D., Jr., Iorio R. Preventing hospital readmissions and limiting the complications associated with total joint arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(11):e60. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsai T.C., Joynt K.E., Wild R.C., Orav E.J., Jha A.K. Medicare's Bundled Payment initiative: most hospitals are focused on a few high-volume conditions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(3):371. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mechanic R., Tompkins C. Lessons learned preparing for Medicare bundled payments. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(20):1873. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1210823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.