Abstract

Objective

To describe the features of 2 unrelated adults with xeroderma pigmentosum complementation group F (XP-F) ascertained in a neurology care setting.

Methods

We report the clinical, imaging, molecular, and nucleotide excision repair (NER) capacity of 2 middle-aged women with progressive neurodegeneration ultimately diagnosed with XP-F.

Results

Both patients presented with adult-onset progressive neurologic deterioration involving chorea, ataxia, hearing loss, cognitive deficits, profound brain atrophy, and a history of skin photosensitivity, skin freckling, and/or skin neoplasms. We identified compound heterozygous pathogenic mutations in ERCC4 and confirmed deficient NER capacity in skin fibroblasts from both patients.

Conclusions

These cases illustrate the role of NER dysfunction in neurodegeneration and how adult-onset neurodegeneration could be the major symptom bringing XP-F patients to clinical attention. XP-F should be considered by neurologists in the differential diagnosis of patients with adult-onset progressive neurodegeneration accompanied by global brain atrophy and a history of heightened sun sensitivity, excessive freckling, and skin malignancies.

Patients with genome instability caused by defects in the DNA damage repair response illustrate the detrimental effect of cumulative DNA damage. This includes heightened cancer risk, accelerated aging, and neurodegeneration. A broad spectrum of neurologic manifestations has been associated with disorders of DNA repair, including xeroderma pigmentosum (XP), Cockayne syndrome (CS), ataxia telangiectasia, trichothiodystrophy, and Nijmegen breakage syndrome.1

XP is a rare autosomal recessive disorder arising from deficient DNA repair. XP is caused primarily by mutations in genes encoding components of the nucleotide excision repair (NER) DNA repair pathway. NER recognizes and repairs several types of DNA lesions, including those due to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, which results in bulky dimers at dipyrimidine sites.2 The typical result is sun damage to exposed skin and eyes. Patients with XP have a high frequency of skin cancer in response to genomic damage caused by UV radiation. Approximately one-fourth of patients with XP experience neurologic deterioration, and when present, shortens life expectancy.3 Cumulative toxicity by non–UV-mediated unrepaired genomic lesions in nonreplicating tissue explains neuronal injury.

We report 2 middle-aged Caucasian women with adult-onset chorea, ataxia, dystonia, neuropathy, and later progressive cognitive impairment, but with life-long acute skin sun-burning on minimal sun exposure, freckle-like skin lesions on sun-exposed skin, and early onset of skin cancer in 1 case. Both were found to have compound heterozygous mutations in ERCC4 and significantly reduced NER capacity, confirming the diagnosis of XP complementation group F (XP-F). Their presentations highlight the importance of adult neurologists considering XP-F when evaluating patients with atypical neurodegeneration.

Methods

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

Patients were referred by their neurologists to participate in the NIH Undiagnosed Diseases Program (UDP). They enrolled in protocol 76-HG-0238 (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00369421) approved by the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained according to protocol guidelines. Both patients had completed extensive clinical evaluations over the preceding decades, including investigations for toxic, metabolic, infectious, autoimmune, and inflammatory processes and had undergone genetic testing for common inherited adult-onset neurodegenerative disorders. Additional clinical details are summarized in the table.

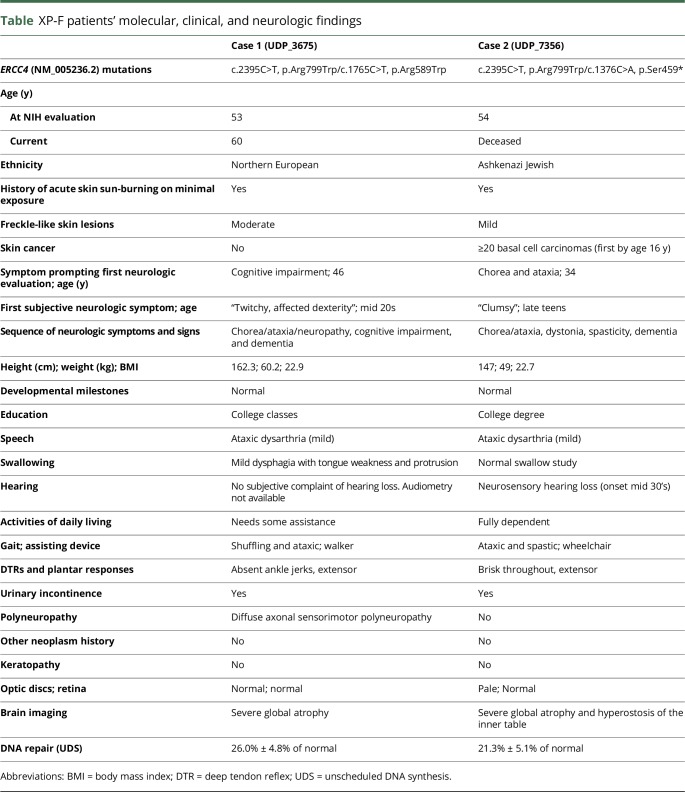

Table.

XP-F patients' molecular, clinical, and neurologic findings

Patient 1

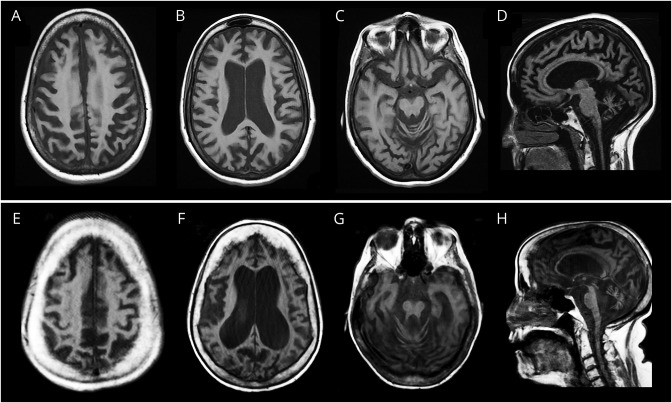

A now 60-year-old woman of Northern European descent with a history of infertility and skin photosensitivity but no skin neoplasms sought medical attention at the age 46 years with 1 year of progressive memory and balance difficulties. Her skin examination revealed moderate freckling of sun-exposed regions (figure 1A). On neurologic examination, she demonstrated mild chorea of her extremities and face, limb ataxia, absent ankle reflexes, and impaired gait. She had 1 sibling with MS but no other similarly affected relatives (figure 1B). Brain MRI showed severe global atrophy out of proportion to her recent symptom onset (figure 2, A–D). EMG and nerve conduction studies indicated diffuse axonal sensorimotor polyneuropathy. A sural nerve biopsy showed decreased myelinated fibers with clusters of regenerating fibers (figure 1D). Neurologic progression was gradual but relentless over the next 11 years; the patient became dependent on a walker for ambulation and deteriorated in essentially all cognitive domains, with an early Mini-Mental State Examination4 score of 26/30, a Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)5 score of 18/30 at 6 years, and an MoCA score of 16/30 at 8 years after her initial visit.

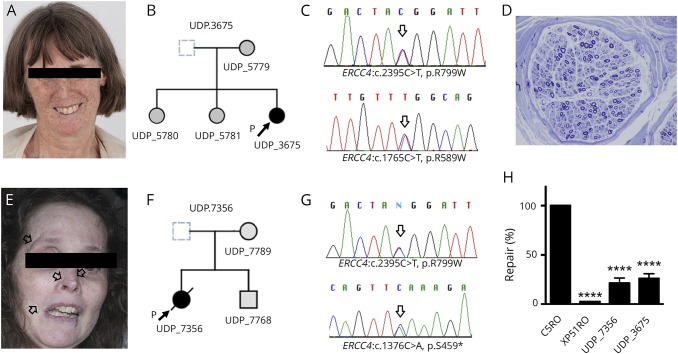

Figure 1. Two cases of XP-F with adult-onset neurologic deterioration.

Patient 1 (top): panels (A–D) and patient 2 (bottom): panels (E–G). (A and E) Face photographs of patients 1 and 2 demonstrating prominent skin freckling (patient 1) or scarring (open arrows) at the sites of prior basal cell carcinoma resections (patient 2). (B and F) Nuclear family pedigrees for patient 1 (UDP_3675) and patient 2 (UDP_7356). (C and G) Sanger chromatogram for patient 1 and patient 2 demonstrating relevant mutations in both ERCC4 alleles (arrows). (D) Representative image of sural nerve biopsy (embedded in Epon and stained with toluidine blue) from patient 1 demonstrating a decrease in the number of myelinated fibers with evidence of degeneration/regeneration clusters (×400). (H) Measurement of UDS in patient fibroblasts. Values are normalized to those obtained for NER-proficient (C5RO) and NER-deficient (XP51RO) control fibroblasts.8 Cells were irradiated with 24 J/m2 UV and then incubated in the presence of the thymidine analog EdU for 2.5 hours to allow DNA repair. AlexaFluor647 was conjugated to EdU by Click-iT chemistry before fixation, stained with DAPI, and quantification of the fluorescence signal in G1 cells measured by flow cytometry. UDS was measured in duplicate for each cell line in 3 independent experiments. Values represent mean ± SD, ****p < 0.0001 by 1-way ANOVA.

Figure 2. Representative axial and sagittal sections of T1-weighted brain MRIs.

Patient 1 (top, A–D) and patient 2 (bottom, E–H) demonstrate prominent and diffuse atrophy in the supra- and infra-tentorial compartments.

Patient 2

A 52-year-old woman of Ashkenazi Jewish descent presented with a 20-year history of progressive dystonia, gait ataxia, hearing loss, and worsening cognition. Her past medical history included photosensitivity with blistering skin lesions after limited sun exposure resulting in multiple facial lentigines and basal cell carcinomas as a teenager. Because of aggressive photoprotection, she had minimal freckling but multiple scars from basal cell carcinoma resections (figure 1E). There was a maternal history of mild postural tremor but no similarly affected relatives (figure 1F). On neurologic examination, the patient was disoriented, partly amnestic, and struggled to follow simple commands. She had dystonic and choreiform movements of the head and neck, a coarse, irregular appendicular tremor, ataxia, and spasticity and was using a wheelchair. She had brisk reflexes and upgoing toes. Brain MRI demonstrated global cerebral atrophy and inner table hyperostosis (figure 2, E–H). There was no electrophysiologic evidence of polyneuropathy. The patient died at age 54 years from secondary medical complications.

Results

Following singleton whole-exome sequencing, variants were prioritized based on known disease association, population frequency, and various in-silico pathogenicity models. Both patients had compound heterozygous mutations in ERCC4 (table). Patient 1 (figure 1C) carried 2 known ERCC4 mutations associated with XP-F; NM_005236.2: c.1765C>T; p.Arg589Trp and c.2395C>T,p.Arg799Trp.6,7 Patient 2 (figure 1G) had the p.Arg799Trp allele and an ultra-rare ERCC4 truncating mutation; NM_005236.2:c.1376C>A, p.Ser459*. Segregation analysis of the families confirmed compound heterozygous allele pairs in both.

NER capacity was investigated by measuring unscheduled DNA synthesis (UDS) determining the incorporation of nucleotides into the nuclear genome of nonreplicating, UV-C irradiated patient-derived fibroblasts (see figure 1 legend for details). The percent repair was obtained by comparing irradiated and unirradiated patient cells to reference standards NER-proficient human fibroblasts (C5RO) and NER-deficient human fibroblasts (XP51RO). XP51RO cells were from a patient with a homozygous p.Arg153Pro ERCC4 mutation associated with a phenotype of XFE progeroid syndrome and severely reduced (<3%) UDS.8 UDS of fibroblasts from patients 1 and 2 had 26.0% ± 4.8% and 21.3% ± 5.1% of the expected NER capacity, respectively, indicating significant NER impairment (figure 1H).

Discussion

The prevalence of XP in the general population approximates 1 in 1 million, being higher in Japan because of a founder mutation in XPA. One-fourth of individuals with XP exhibit neurologic manifestations including acquired microcephaly, neuropathy, sensorineural hearing loss, and progressive cognitive impairment. In a long-term follow-up study of 89 patients with XP in the United Kingdom, three patients were diagnosed with XP-F, one of whom demonstrated neurologic features similar to our patients.9 Up to 10% of all XP is XP-F.3,10 XP-F is caused by mutations in the ERCC4 gene. The encoded ERCC4/XPF protein forms a tight complex with the ERCC1 protein. This heterodimer provides 5′-nuclease activity for a crucial excision step of NER.2

Compared with other XP subtypes, patients with XP-F have less propensity for skin neoplasms and present later, often past the 4th decade.10 Neurodegeneration is largely reported in younger patients in complementation groups XP-A, XP-B, XP-D, and XP-G but not in XP-C or XP-E and is often heralded by progressive neurosensory hearing loss.3 Neurologic features reported in XP-F include gait disturbances, ataxia, neuropathy, chorea, sensorineural hearing loss, cognitive decline, and cerebral and cerebellar atrophy.6,7,10 Our observations support reports suggesting that ERCC4: p.Arg799Trp might be a common allele among XP-F patients with adult-onset neurodegeneration.6 Besides XP-F, ERCC4 mutations are associated with other diseases, including XFE progeria with very low UDS, Fanconi Anemia, and XP/CS.3,8

Like other reported XP-F cases with neurodegeneration, our patients manifested disparity between severity of brain atrophy by MRI at the time of first imaging and relatively modest early cognitive deficits, consistent with compensation of a very slow neurodegenerative process over decades. This contrasts with other neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer disease, in which profound impairment usually accompanies such severe degree of brain atrophy.

These cases elicit consideration of several points. First, dysfunction of the NER pathway can be associated with profound neurodegeneration. Second, there is a causal role of cumulative unrepaired DNA damage in neurodegenerative disorders in general. The precise type of damage leading to neurodegeneration is unclear but may relate to stable oxidative genomic lesions. Finally, the diagnosis of XP, and particularly XP-F, should be considered in adult patients with unexplained neurodegeneration associated with global brain atrophy, especially when accompanied by a history of photosensitivity, skin malignancies, and/or excessive freckling.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank their patients, their families, and referring physicians. Dr. Dennis Landis contributed to the clinical evaluations of these patients at the NIH.

Glossary

- CS

Cockayne syndrome

- MoCA

Montreal Cognitive Assessment

- NER

Nucleotide excision repair

- UDP

Undiagnosed Diseases Program

- UDS

unscheduled DNA synthesis

- UV

ultraviolet

- XP

xeroderma pigmentosum

- XP-F

XP complementation group F

Author contributions

N.M. Shanbhag: wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. M.D. Geschwind, J.J. DiGiovanna, C. Groden, and R. Godfrey: clinical consult and contributed to manuscript writing. M.J. Yousefzadeh: measured NER in fibroblasts, interpretation of data, and contributed to manuscript writing. E.A. Wade and L.J. Niedernhofer: measured NER in fibroblasts, interpretation of data, data analysis, and contributed to manuscript writing. M.C.V. Malicdan: interpretation of data, data analysis, sample logistics, and contributed to manuscript writing. K.H. Kraemer: study design, interpretation of data, and contributed to manuscript writing. W.A. Gahl: study design, contributed to manuscript writing, and funding acquisition. C. Toro: study design, clinical consult, interpretation of data, data analysis, and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript.

Study funding

Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) NHGRI and the NCI, Common Fund, Office of the Director; the NIH/NHLBI grant (HHSN268201400058); the NIH/NIA grant (P01AG043376): M.J.Y., E.A.W. and L.J.N.; and the Michael J. Homer Family Fund: M.D.G.

Disclosure

Dr. Shanbhag has received research support from the NIH NINDS and Alzheimer's Association. Dr. Geschwind has received funding for travel and/or speaker honoraria from Oakstone Publishing, Inc; has served on the editorial board of Dementia & Neuropsychologia; serves or has served as a consultant to Advanced Medical Inc, Best Doctors Inc, Grand Rounds, Gerson Lehrman Group Inc, Guidepoint Global, MEDACorp, LCN Consulting, Optio Biopharma Solutions, various medical-legal consulting, Biohaven Pharmaceuticals Inc, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and Quest Diagnostics; and receives or has received research support from the NIH/NIA (R01 AG031189) PI 2013-2018, Alliance Biosecure, Michael J. Homer Family Fund, CurePSP, and Tau Consortium. Dr. DiGiovanna serves or has served on scientific sdvisory boards of the Medical and Scientific Advisory Board of the Foundation for Ichthyosis and Related Skin Types; holds patents with regard to the use of synthetic peptides to disrupt the cytoskeleton and therapeutic uses of hmgn1 and hmgn2; consults or has consulted for the US Food and Drug Administration; and is employed by the National Cancer Institute and NIH. Dr. Groden, Dr. Godfrey, and Dr. Yousefzadeh report no disclosures. Dr. Wade is or has been employed by The Scripps Research Institute and The National Institute on Aging. Dr. Niedernhofer holds patents with regard to a rapid test to measure DNA repair capacity of an individual; has received research support from the NIH/NHLBI, NIH/NIA, and Glenn Award for Aging Research. Dr. Malicdan serves or has served on the editorial board of BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders; holds patents with regard to therapeutic pharmaceutical agent for diseases associated with decrease in function of gne protein, food composition, and food additive, Gne-/-hGNED176VTg as a mouse model for DMRV/HIBM and CANNABINOID RECEPTOR MEDIATING COMPOUNDS; and is employed by the NIH Intramural Research Program. Dr. Kraemer serves or has served on the editorial board of Photodermatology and Photoimmunology. Dr. Gahl has received funding for travel and/or speaker honoraria from Cystinosis Research Network; serves or has served on the editorial board of Molecular Genetics and Metabolism; receives or has received licensing royalties from ManNAc; and receives research support from the NIH. Dr. Toro is a full-time employee of the NIH and receives funding from the NIH intramural program. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/NG.

References

- 1.McKinnon PJ. DNA repair deficiency and neurological disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 2009;10:100–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sijbers AM, de Laat WL, Ariza RR, et al. Xeroderma pigmentosum group F caused by a defect in a structure-specific DNA repair endonuclease. Cell 1996;86:811–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kraemer KH, DiGiovanna JJ. Xeroderma pigmentosum. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., editors. GeneReviews((R)). Seattle: University of Washington; 1993–2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:695–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gregg SQ, Robinson AR, Niedernhofer LJ. Physiological consequences of defects in ERCC1-XPF DNA repair endonuclease. DNA Repair (Amst) 2011;10:781–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moriwaki S, Nishigori C, Imamura S, et al. A case of xeroderma pigmentosum complementation group F with neurological abnormalities. Br J Dermatol 1993;128:91–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niedernhofer LJ, Garinis GA, Raams A, et al. A new progeroid syndrome reveals that genotoxic stress suppresses the somatotroph axis. Nature 2006;444:1038–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fassihi H, Sethi M, Fawcett H, et al. Deep phenotyping of 89 xeroderma pigmentosum patients reveals unexpected heterogeneity dependent on the precise molecular defect. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016;113:E1236–E1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tofuku Y, Nobeyama Y, Kamide R, Moriwaki S, Nakagawa H. Xeroderma pigmentosum complementation group F: report of a case and review of Japanese patients. J Dermatol 2015;42:897–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]