Highlights

-

•

A hybrid laparoscopic and percutaneous repair for incisional hernia was described.

-

•

Percutaneous defect closure can be indicated for large hernia (>10 cm in diameter).

-

•

Mesh fixation should be limited below the costal margin in subcostal hernia.

-

•

Minimal organ injuries and obtaining more overlap are the advantages.

-

•

Postoperative pain is the disadvantage.

Keywords: Incisional hernia, Subcostal region, Laparoscopic repair, Percutaneous repair, Defect closure

Abstract

Introduction

Optimal surgery for a midline incisional hernia extending to the subcostal region remains unclear. We report successful hybrid laparoscopic and percutaneous repair for such a complex incisional hernia.

Presentation of case

An 85-year-old woman developed a symptomatic incisional hernia after open cholecystectomy. Computed tomography revealed a 14 × 10 cm fascial defect.

Four trocars were placed under general anesthesia. Percutaneous defect closure was performed using multiple non-absorbable monofilament threads, i.e., a “square stitch.” Each thread was inserted into the abdominal cavity from the right side of the defect and pulled out to the left side. The right side of the thread was subcutaneously introduced anterior to the hernia sac. The threads were sequentially tied in a cranial to caudal direction. A multifilament polyester mesh with resorbable collagen barrier was selected and fixed using absorbable tacks with additional full-thickness sutures. The cranial-most limit of mesh fixation was at the level of the subcostal margin, and the remaining part was draped over the liver surface.

The postoperative course was uneventful, with no seroma, mesh bulge, or hernia recurrence at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months of follow-up.

Discussion

The advantages of our technique are the minimal effect on the scar in the midline during defect closure, the minimal damage to the ribs and obtaining more overlap during mesh fixation. The disadvantage is the postoperative pain.

Conclusion

Our proposed hybrid surgical approach may be considered as the treatment of choice for a large midline incisional hernia extending to the bilateral costal region.

1. Introduction

Surgical repair of a subcostal hernia has generally been performed with a conventional retromuscular approach, with a low recurrence rate [1]. Recently, a multicenter Italian study showed that a subcostal hernia could be successfully repaired by laparoscopic surgery, with no conversion to open surgery and no hernia recurrence [2]. They also reported the fastest operative time in the subcostal group among the non-midline ventral hernias, and the reason might be explained by easier port placement and adhesiolysis for ‘localized defect’ in the subcostal region [2]. However, mesh fixation with laparoscopic repair for a subcostal hernia can be technically challenging, because minimal surrounding tissue and proximity to bony structures restricts mesh fixation technique [3], [4]. For subcostal hernias, various mesh fixation techniques have been proposed using tacks, sutures, glue or combination of these materials [2], [3], [4].

In contrast, laparoscopic repair for a midline incisional hernia is an established surgical technique with guidelines [5], [6], [7]. In addition, fascial defect closure can be performed either extracorporeally or intracorporeally, that potentially reduces the mesh bulge, seroma formation, or hernia recurrence [8], [9], [10], [11]. Recent studies have advocated defect closure for a large midline incisional hernia, which is typically defined as transverse diameter of equal to or greater than 10cm [8], [12].

Despite advances in laparoscopic repair, the optimal surgical strategy for a large incisional hernia involving both the midline and subcostal region remains unclear because of topographic complexity. To our knowledge, there has been no supportive report to resolve this specific surgical problem.

We report a case in which successful hybrid laparoscopic and percutaneous repair of a large midline incisional hernia extending to the bilateral subcostal region was performed. This work has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [13].

2. Presentation of case

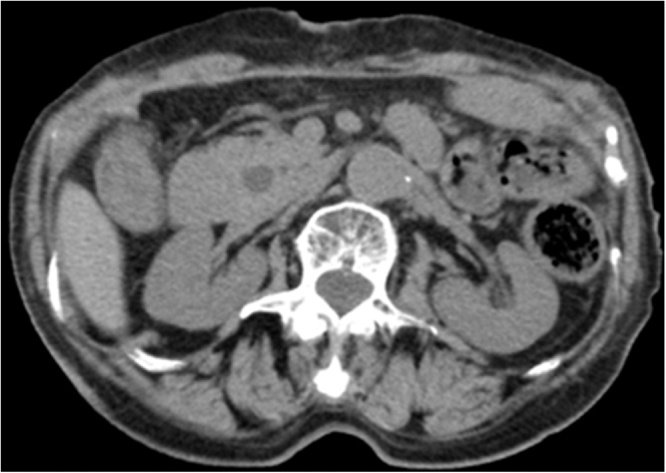

An 85-year-old woman was referred to our hospital with the diagnosis of symptomatic incisional hernia after open cholecystectomy. She had no significant past medical history except for hyperlipidemia. She was well-nourished and reported a long history of abdominal distention with a bulge. Her height was 147 cm, with weight 46.5 kg and a body mass index of 21.5 kg/m2. She had an incisional scar with massive keloid formation in the midline, extending upward to the xiphoid. In the upright position, a bulging mass with a diameter of 18 cm was observed, and the uppermost contour involved the bilateral subcostal margins. Computed tomography (CT) visualized a 14 cm (longitudinal) × 10 cm (horizontal) fascial defect in the upper abdomen (Fig. 1). She requested surgery for her long-standing symptoms and we decided on hybrid surgery combining a laparoscopic and percutaneous approach.

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography visualized a 10-cm, horizontal fascial defect (arrows at both ends).

Under general anesthesia, the patient was placed in a supine position. The first trocar (12 mm) was placed under direct vision at the left midaxillary line. Two trocars (5 mm) were placed in the left upper and lower quadrant to achieve a co-axial setting. During surgery, an additional trocar (5 mm) was placed in the right lower quadrant to facilitate mesh fixation.

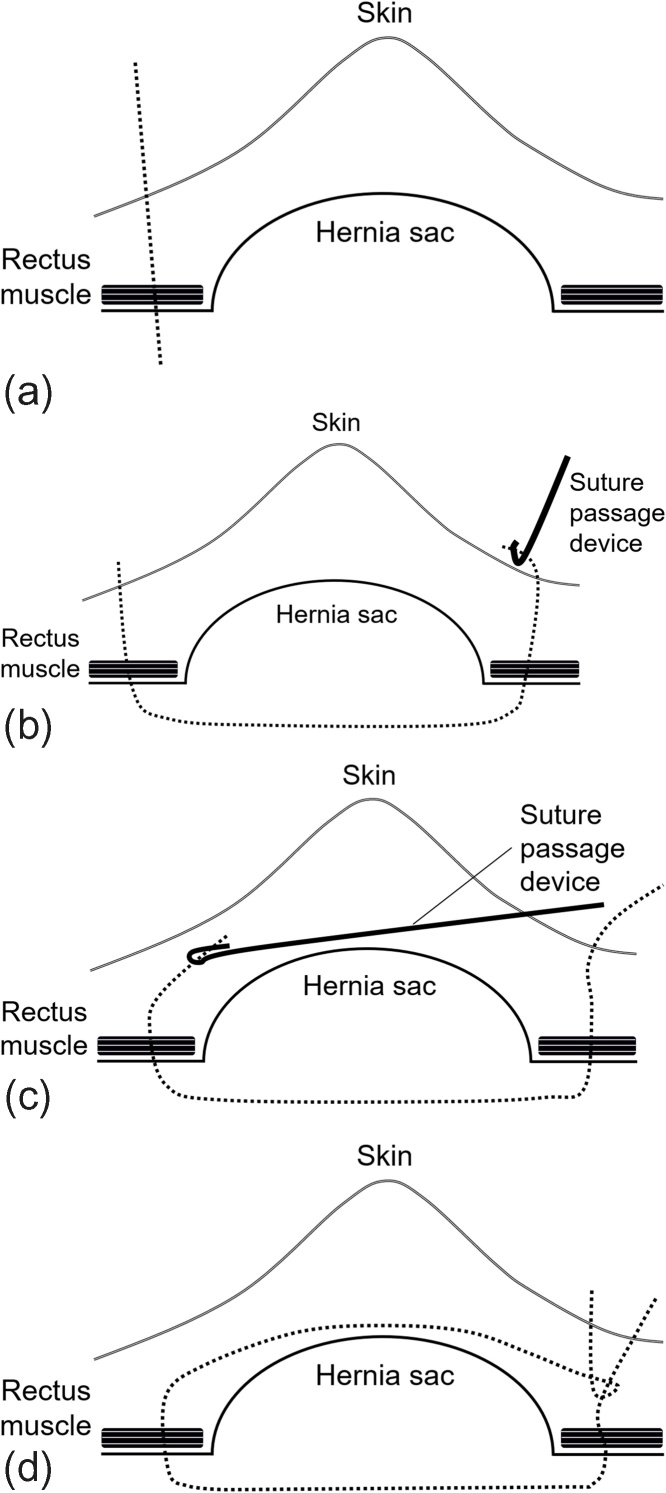

After lysis of adhesions, percutaneous defect closure was performed with a modified technique described in previous report [14]. The schematic presentation of this percutaneous defect closure is shown in Fig. 2, i.e., a “square stitch.”

Fig. 2.

(a) A non-absorbable monofilament thread (dotted line) was perpendicularly inserted into the abdominal cavity. (b) A suture passage device was inserted into the abdominal cavity for the other side and the thread (dotted line) was pulled out to the skin. (c) A suture passage device was subcutaneously inserted and passed anterior to the hernia sac. (d) The thread was caught and pulled through with the suture passage device. The threads were sequentially tied and the knots were buried under the skin.

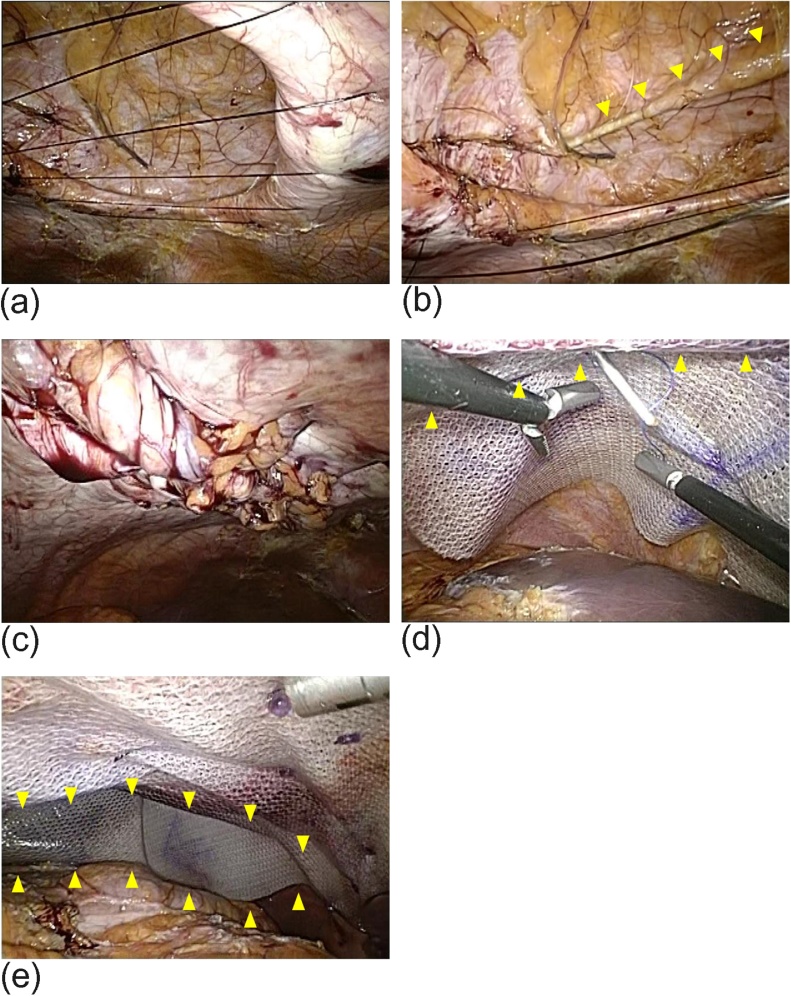

Initially, the contour of the defect was marked on the skin using a 23-G spinal needle under desufflated laparoscopic vision. A transverse line 1 cm lateral to the defect margin was drawn with skin marking ink. Surgery commenced at the most cranial site of the defect and continued to the most caudal site. The interval between lines was approximately 2 cm (Fig. 3a). After a small subcutaneous incision was made, a non-absorbable monofilament thread (2-0 Monosof™, Medtronic plc, Dublin, Ireland) was perpendicularly inserted into the abdominal cavity from the right edge of the line. Then, a suture passage device (Endoclose™, Medtronic) was inserted into the abdominal cavity for the left edge of the line, and the thread was pulled out to the skin. Subsequently, the suture passage device was subcutaneously inserted from the left edge of the line and was passed anterior to the hernia sac (Fig. 3b). The right side of the thread was caught and pulled through to the left side with the suture passage device. Finally, the threads were sequentially tied in a cranial to caudal direction (Fig. 3c), and the knots were buried under the skin.

Fig. 3.

(a) Intraabdominal view of the threads for percutaneous defect closure. The interval of each thread was approximately 2 cm. (b) A suture passage device was subcutaneously inserted and passed anterior to the hernia sac (arrow heads). (c) The threads were sequentially tied in a cranial to caudal direction. (d) The cranial-most limit of mesh fixation was at the level of the subcostal margin (arrowheads). (e) The remaining part of the mesh was draped over the liver surface without tacking (arrowheads).

A 25 × 20 cm multifilament polyester mesh with resorbable collagen barrier (Parietex™ composite mesh, Medtronic) was selected in ordered to obtain a 5-cm overlap for the defect. The mesh was fixed with absorbable tacks (Absorbatack™, Medtronic) at 1-1.5-cm intervals with double-crown technique. This was followed with additional full-thickness sutures using non-absorbable monofilament (2-0 Prolene™, Ethicon, Cincinnati, OH, USA) to reinforce the mesh fixation. The cranial limit of mesh fixation was at the level of the subcostal margin (Fig. 3d). The remaining part of the mesh was draped over the liver surface without tacking (Fig. 3e). Each incision was closed with subcuticular stitches.

The operative time was 247 min. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged home on the 10th postoperative day. The patient did not experience any significant postoperative complications. Follow-up evaluation was done at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery. Analgesic agents were discontinued at 1 month. CT was performed at 3 and 12 months (Fig. 4). There was no clinically or radiographically significant seroma, mesh bulge, or hernia recurrence at each follow-up.

Fig. 4.

Follow-up computed tomography at 12 months after surgery. There was no radiographically significant seroma, mesh bulge, or hernia recurrence.

3. Discussion

In this case, laparoscopic and percutaneous repair was successful for a large midline incisional hernia extending to the bilateral subcostal region.

Laparoscopic repair for an incisional hernia is generally indicated for a mean defect size of 10 cm [6], with a maximum diameter of 18 cm recently reported [15]. In addition, fascial defect closure has been advocated for reduction of seroma [6], [9], mesh bulge [6], [10], and recurrence rates [9], [10], although conflicting reports have also been published [11], [16]. A recent study showed that defect closure with intraperitoneal onlay mesh (IPOM-plus) was more effective than standard intraperitoneal onlay mesh (sIPOM) in terms of reducing mesh bulge, for large hernias (greater than 10 cm in diameter) [12]. In the present case, the defect size was 14 cm (longitudinal) × 10 cm (horizontal). Because our goal was the relief from her long-standing abdominal distension with a bulge, we selected a hybrid laparoscopic and percutaneous approach to securely perform defect closure.

The advantage of our technique is the minimal effect on the scar in the midline incision. The surgical technique we used was comparable to that in a previous report, with some modifications [14]. In the previous report, the subcutaneous threads for closing the defect were tied in the midline where some scar tissue may persist [14], whereas that of ours were tied in the left lateral side (Fig. 2). Our approach seems easier because we simply penetrate the suture passage device subcutaneously from the right side to the left side.

The other advantage is the minimal damage to the ribs. Mesh fixation is challenging for a subcostal hernia. The SAGES guidelines warn against possible injuries to the lung, pericardium, diaphragm, and neurovascular bundles along the inferior surface of ribs during fixation above the costal margins [5]. Furthermore, the guidelines recommended draping mesh over the diaphragm superiorly without fixation, as an alternative and safer option to prosthetic fixation [5]. In this case, the cranial limit of mesh fixation was at the level of the subcostal margin. The remaining part of the mesh was draped over the liver surface without tacking. We believe that this mesh placement can obtain more overlap from the most cranial edge of the defect, and this issue has not been discussed in the previous reports [3], [4], [17]. In addition, we suggest that this procedure must be carried out using mesh with an anti-adhesive barrier, to prevent possible bowel-to-mesh adhesions.

The disadvantage of our technique is postoperative pain. It took 1 month for discontinuing analgesic agents. Although a meta-analysis demonstrated that postoperative pain with defect closure appeared to be transient [6], a recent study showed that 14% of patients with IPOM-plus had pain at 3 months whereas those with sIPOM did not experience such pain [12]. Defect closure inevitably oppose to the ‘tension-free concept’ in hernia surgery. The possibility of chronic pain should be carefully informed to the patient before surgery, because persistent postoperative pain certainly negates the cosmetic benefit from surgery, particularly in large incisional hernia.

Regardless of the surgical techniques, we should keep in mind that the recurrence rate is higher for larger hernias measuring 10–15 cm [14], [17], [18]. In this case, a favorable surgical outcome was achieved only in a short-term. A long-term follow-up is necessary, and we will continue to evaluate our surgical strategy for incisional hernias.

4. Conclusion

Our proposed hybrid laparoscopic and percutaneous approach may be considered as the treatment of choice for a large midline incisional hernia extending to the bilateral costal region. Surgical approach must be carefully considered before surgery for a complex incisional hernia, as the defect size and hernia location can affect surgical technique. Larger case series or prospective studies are needed to determine the optimal surgical approach for a large midline incisional hernia extending to the bilateral costal region.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The institutional ethics committee determined that approval was not necessary for a case report.

Consent

Written consent for the publication of this case report with accompanying images was obtained from the patient. The consent was written in Japanese for better understanding by the patient. The consent form will be provided to the editors of this journal on request.

Author contribution

Study conception and design: Tsujinaka, Nakabayashi.

Data acquisition and interpretation: Tsujinaka, Nakabayashi.

Surgery and patient follow-up: Tsujinaka, Nakabayashi, Kakizawa, Kikugawa.

Surgical technical adviser: Nakabayashi.

Drafting the paper: Tsujinaka.

Critical revision of manuscript: Nakabayashi, Toyama, Rikiyama.

Final approval for submitting the manuscript; Tsujinaka, Nakabayashi, Kakizawa, Kikugawa, Toyama, Rikiyama.

Registration of research studies

We have carefully read the Research Registry website. There is a statement ‘We do not register case reports that are not first-in-man or animal studies’ on the webpage.

Therefore, it is not necessary to register this case report.

Guarantor

Shingo Tsujinaka, the corresponding author of this paper.

Contributor Information

Shingo Tsujinaka, Email: tsujinakas@omiya.jichi.ac.jp.

Yukio Nakabayashi, Email: y-nakabayashi@jikei.ac.jp.

Nao Kakizawa, Email: kmwwn529@yahoo.co.jp.

Rina Kikugawa, Email: rinamorita@nifty.com.

Nobuyuki Toyama, Email: ntoyama@omiya.jichi.ac.jp.

Toshiki Rikiyama, Email: trikiyama@jichi.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Veyrie N., Poghosyan T., Corigliano N., Canard G., Servajean S., Bouillot J.L. Lateral incisional hernia repair by the retromuscular approach with polyester standard mesh: topographic considerations and long-term follow-up of 61 consecutive patients. World J. Surg. 2013;37:538–544. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1857-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrarese A., Enrico S., Solej M., Surace A., Nardi M.J., Millo P. Laparoscopic management of non-midline incisional hernia: a multicentric study. Int. J. Surg. 2016;33(Suppl. 1):S108–S113. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lal R., Sharma D., Hazrah P., Kumar P., Borgharia S., Agarwal A. Laparoscopic management of nonmidline ventral hernia. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. A. 2014;24:445–450. doi: 10.1089/lap.2013.0381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yee J.A., Harold K.L., Cobb W.S., Carbonell A.M. Bone anchor mesh fixation for complex laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Surg. Innov. 2008;15:292–296. doi: 10.1177/1553350608325231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Earle D., Roth J.S., Saber A., Haggerty S., Bradley J.F., 3rd, Fanelli R. SAGES guidelines for laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Surg. Endosc. 2016;30:3163–3183. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5072-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tandon A., Pathak S., Lyons N.J., Nunes Q.M., Daniels I.R., Smart N.J. Meta-analysis of closure of the fascial defect during laparoscopic incisional and ventral hernia repair. Br. J. Surg. 2016;103:1598–1607. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soliani G., De Troia A., Portinari M., Targa S., Carcoforo P., Vasquez G. Laparoscopic versus open incisional hernia repair: a retrospective cohort study with costs analysis on 269 patients. Hernia. 2017;21:609–618. doi: 10.1007/s10029-017-1601-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chelala E., Barake H., Estievenart J., Dessily M., Charara F., Alle J.L. Long-term outcomes of 1326 laparoscopic incisional and ventral hernia repair with the routine suturing concept: a single institution experience. Hernia. 2016;20:101–110. doi: 10.1007/s10029-015-1397-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Light D., Bawa S. Trans-fascial closure in laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Surg. Endosc. 2016;30:5228–5231. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-4868-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitura K., Skolimowska-Rzewuska M., Garnysz K. Outcomes of bridging versus mesh augmentation in laparoscopic repair of small and medium midline ventral hernias. Surg. Endosc. 2017;31:382–388. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-4984-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wennergren J.E., Askenasy E.P., Greenberg J.A., Holihan J., Keith J., Liang M.K. Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair with primary fascial closure versus bridged repair: a risk-adjusted comparative study. Surg. Endosc. 2016;30:3231–3238. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4644-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suwa K., Okamoto T., Yanaga K. Is fascial defect closure with intraperitoneal onlay mesh superior to standard intraperitoneal onlay mesh for laparoscopic repair of large incisional hernia? Asian J. Endosc. Surg. 2018 doi: 10.1111/ases.12471. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saeta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P. The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshikawa K., Shimada M., Kurita N., Sato H., Iwata T., Higashijima J. Hybrid technique for laparoscopic incisional ventral hernia repair combining laparoscopic primary closure and mesh repair. Asian J. Endosc. Surg. 2014;7:282–285. doi: 10.1111/ases.12113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nardi M., Jr., Millo P., Brachet Contul R., Lorusso R., Usai A., Grivon M. Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair with composite mesh: analysis of risk factors for recurrence in 185 patients with 5 years follow-up. Int. J. Surg. 2017;40:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karipineni F., Joshi P., Parsikia A., Dhir T., Joshi A.R. Laparoscopic-assisted ventral hernia repair: primary fascial repair with polyester mesh versus polyester mesh alone. Am. Surg. 2016;82:236–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moreno-Egea A., Carrillo-Alcaraz A. Management of non-midline incisional hernia by the laparoscopic approach: results of a long-term follow-up prospective study. Surg. Endosc. 2012;26:1069–1078. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-2001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hesselink V.J., Luijendijk R.W., de Wilt J.H., Heide R., Jeekel J. An evaluation of risk factors in incisional hernia recurrence. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1993;176:228–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]