Abstract

Functional deficits in sensory systems are commonly noted in neurodevelopmental disorders, such as the Rett syndrome (RTT). Defects in methyl CpG binding protein gene (MECP2) largely accounts for RTT. Manipulations of the Mecp2 gene in mice provide useful models to probe into various aspects of brain development associated with the RTT. In this study, we focused on the somatosensory cortical phenotype in the Bird mouse model of RTT. We used voltage-sensitive dye imaging to evaluate whisker sensory evoked activity in the barrel cortex of mice. We coupled this functional assay with morphological analyses in postnatal mice and investigated the dendritic differentiation of barrel neurons and individual thalamocortical axon (TCA) arbors that synapse with them. We show that in Mecp2-deficient male mice, whisker-evoked activity is roughly topographic but weak in the barrel cortex. At the morphological level, we find that TCA arbors fail to develop into discrete, concentrated patches in barrel hollows, and the complexity of the dendritic branches in layer IV spiny stellate neurons is reduced. Collectively, our results indicate significant structural and functional impairments in the barrel cortex of the Bird mouse line, a popular animal model for the RTT. Such structural and functional anomalies in the primary somatosensory cortex may underlie orofacial tactile sensitivity issues and sensorimotor stereotypies characteristic of RTT.

Keywords: axon, barrel cortex, dendrite, neural activity, Rett syndrome, voltage-sensitive dye imaging, RRID: MGI:3817236, RRID: IMSR_JAX:000664

1 | INTRODUCTION

Rett syndrome (RTT) is a neurodevelopmental disorder caused by mutations in the MECP2 gene on the X chromosome located at Xq28 (Amir et al., 1999). MECP2 acts as a transcription repressor or activator of many genes throughout the genome and its loss of function or over-expression leads to cognitive and behavioral deficits observed in childhood development (Calfa, Percy, & Pozzo-Miller, 2011; Kaufmann, Johnston, & Blue, 2005; Na, Nelson, Kavalali, & Monteggia, 2013). In the mouse brain, Mecp2 protein and mRNA expression is widespread, and conspicuous in the thalamus and neocortex (Dragich, Kim, Arnold, & Schanen, 2007; Jung et al., 2003; Kishi & Macklis, 2004). Several studies have examined aspects of dendritic differentiation, spine genesis, and electrophysiological properties of Mecp2 mutant neurons in different regions of the mouse brain, such as the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex. However, no systematic study has been done in the developing somatosensory (barrel) cortex in Mecp2 constitutive or region-specific mutants to investigate how Mecp2 deletion affects the thalamocortical synaptic circuitry of the somatosensory system.

Mecp2 is X-linked and mutant homozygous female mice do not survive; males carrying the mutation (−/y) survive and are considered Mecp2-null. Mecp2 null mice exhibit several characteristics of RTT at 3–8 weeks of age, while heterozygous female mice exhibit some of the characteristics of RTT after 6 months. Several research groups have generated Mecp2 mutant mouse lines. The initial constitutive Mecp2 deletion resulted in embryonic lethality (Tate, Skarnes, & Bird, 1996). Adrian Bird’s laboratory circumvented embryonic lethality by conditional gene deletion approach. The resultant mouse line is known as the Bird model (Guy, Hendrich, Holmes, Martin, & Bird, 2001). Breeding Mecp2 heterozygous (Mecp2+/−) females with C57BL/6 males yield heterozygous females and hemizygous (Mecp2−/y) males; hemizygous males do not breed.

In many neurodevelopmental disorders, such as RTT, sensory processing deficits are common. A conspicuous behavioral stereotypy in children with RTT is hand to mouth kneading movements, which has both tactile sensory and motor components. In the human primary somatosensory cortex, proportionately largest areas are devoted to the hands and mouth. Likewise, in the mouse primary somatosensory cortex, a very large area is devoted to the representation of the facial whiskers. In fact, each whisker has a distinct, corresponding neural module known as a “barrel” because of the arrangement of layer IV neurons in a cylindrical array, with its center (hollow) filled by the discrete terminal arbors of thalamocortical axon (TCA) arbors corresponding to single whiskers (Agmon, Yang, Jones, & O’Dowd, 1995; Lee, Iwasato, Itohara, & Erzurumlu, 2005; Rebsam, Seif, & Gaspar, 2002; Senft & Woolsey, 1991; Woolsey & Van der Loos, 1970). Thus, the whisker-barrel pathway of mice provides a unique model to study sensory processing defects in mutant mouse models of neurodevelopmental disorders.

In this study, we investigated peripherally evoked sensory activity in the barrel cortex of male Mecp2 null mice and present analysis of the morphological differentiation of TCA terminals and dendrites of the barrel cells that receive peripherally evoked activity through them.

2 | MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 | Animals and brain samples

We bred the mice in house using Mecp2 heterozygous (Mecp2+-−) females (B6.129P2(C)-Mecp2tm1.1Bird/J [Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME], RRID: MGI:3817236) and C57BL/6 (Mecp2+/y) male (RRID: IMSR_JAX:000664). In all experiments, we used male offsprings, Mecp2−/y (null phenotype) and Mecp2+/y (controls). We genotyped the postnatal mice from our Mecp2 colony by preparing DNA from tail samples and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis, as previously described (Lo, Blue, & Erzurumlu, 2016). All animal handling was in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (ISBN:13:978-0-309–15400-0, revised in 2011) and a protocol approved by the University of Maryland, Baltimore Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

For morphological analyses, the mice were overdosed in a regulated anesthesia machine induction chamber with 5% isoflurane. Upon reaching a deep surgical plane of anesthesia, we performed bilateral thoracotomy and perfused transcardially with saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Next, we extracted the brains and kept them in the same fixative overnight before processing for carbocyanine dye labeling as described below.

All morphological experiments were done in a masked fashion, where the investigator collecting the data was unaware of the genotype of the animal.

2.2 | Voltage-sensitive dye optical imaging

We imaged single whisker-evoked activity (E2 whisker) in the barrel cortex of five Mecp2−/y and five control (Mecp2+/y) mice, varying in age from 1 to 2 months. Following urethane anesthesia (15% solution in sterile double distilled water, 1.15 g/kg body weight intraperitoneal injection with a 25 gauge syringe needle), we placed the mice in a stereotaxic frame and performed craniotomy. We humidified the exposed surface with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF), cleaned any tissue debris with a hemostatic sponge and applied voltage-sensitive dye RH-1691 (Optical Imaging Ltd, Rehovot, Israel; 1.0 mg/ml in ACSF) for 1 hr. Afterward, we rinsed the exposed surface again with ACSF and then covered it with high density silicone oil and a 0.1-mm-thick coverslip.

The imaging window was positioned below the objective of a MiCAM02 system (Brain Vision Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The focusing plane was adjusted to the depth of 300 μm below the dura mater. We imaged the left parietal cortex. Mice have five curved rows of mystacial whiskers, each row lettered A–E from dorsal to ventral and each whisker in a row numbered. Before imaging sessions, we clipped all the whiskers except E2 whisker on the right snout of the mouse. For controlled whisker stimulation, a glass capillary (1.0 mm in diameter) fitted onto an XYZ manipulator was aimed above the intact E2 whisker, and 10 ms duration air puffs (~45 kPA) were applied through a Picospitzer controlled by the MiCAM02 imaging system. Each puff moves the E2 whisker 1 mm in the dorsoventral direction. This set up allowed us to stimulate the E2 whisker and record the consequent fluorescence signal changes in synchrony.

At the start of each optical imaging session, we obtained a gray-scale image of the dural surface and saved it as a graphic file. Each experiment consisted of 100 trials with 500 frames per trial. Whisker stimulation (air puff) was delivered at the 250th frame, one trial per stimulus and the intertrial interval was 12 s. We calculated the change in fluorescence as ΔF/F (%) using the BrainVision Analyzer. ΔF/F denotes the difference in fluorescence intensity at resting state before stimulation and the change in intensity after stimulation. We generated a pseudocolor map using first frame analysis and then by averaging the data for each session (Ferezou, Bolea, & Petersen, 2006; Tsytsarev, Pope, Pumbo, Yablonskii, & Hofmann, 2010). Image acquisition, whisker stimulation, calculation of ΔF/F, and generation of pseudocolor maps were all done by computer and imaging programs, obviating any experimenter bias.

We use MiCAM02 system for imaging, which allows the user to calculate the standard deviation to quantify the degree of variation or dispersion within a data set from single imaging sessions. In all our imaging sessions, we found that the first, the last, and the in-between trials of a set of 100, the repeatability of the whisker-evoked response was consistent within the individual animals and genotype.

2.3 | Carbocyanine dye labeling of TCAs

Single TCA labeling and arbor reconstruction experiments were done in postnatal (P7) pups for the following reasons: (a) Carbocyanine dye labeling in fixed tissues works best before myelination is complete; otherwise, the lipophilic dye gets trapped in myelin lamellae and does not diffuse along the length of the axon. (b) TCA axon arbor patterns are established in mice by P7. (c) We and others have used this labeling approach and detailed the development of TCA arbors with respect to cellular barrels in wild type and a variety of transgenic mouse lines (Ballester-Rosado et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2005; Rebsam et al., 2002; Suzuki et al., 2015). The results from the current study allows comparison with all the other reports on P7 TCA axon arbors in the barrel cortex of normal and mutant mice.

We euthanized and perfused the mouse pups (as described above, in Section 2.1) at postnatal day 7. We extracted the brains and postfixed them in 4% PFA overnight. Next day, we cut sections at an oblique angle to preserve the thalamocortical projections (Lee et al., 2005). We collected two to three thick sections (250 μm) for TCA labeling. We selected a small crystal of DiI (1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) with a 30-gauge needle and inserted the crystal into the ventroposteromedial (VPM) nucleus of the thalamus under a dissection microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Sections were then placed in the fixative and kept in dark for 2–3 weeks for dye diffusion. Sections containing DiI-labeled TCAs were then mounted on glass slides, and coverslipped with fluorescence mounting medium.

We examined the DiI-labeled TCAs under a Leica TCS SP2 confocal microscope (Heidelberg, Germany). We identified specimens in which a single axon could be traced from the internal capsule into the barrel field. Reconstructions were made from image stacks using ImageJ (NIH) and Photoshop (Adobe, San Jose, CA). We quantified the number of terminal tips and measured the length of the lateral extent of each individual afferent arbor as described before (Lee, 2009).

2.4 | Golgi-Cox impregnation and morphometric analyses

We took brain samples from young (30–45 days old) Mecp2−/y and Mecp2+/y (control) male mice (n = 3 each), flattened the cortices, immersed them in Golgi-Cox impregnation solution for 2–3 weeks and then cut at a thickness of 100 μm using a vibratome as previously described (Chu, Yen, & Lee, 2013). We chose layer IV spiny stellate cells for morphological examinations using the following criteria: (a) location in the barrel wall; (b) spiny appearance; and (c) oriented dendrites. We collected isolated barrel cells that fulfilled these three criteria, in an investigator unaware of the genotype fashion. Our analyses were based on 18 neurons from three control and 37 neurons from three mutant mice.

We acquired stacks of images, reconstructed the neurons and analyzed them using Neurolucida software (Microbrightfield Bioscience, Williston, VT) as previously described (Chu et al., 2013). We used Sholl and branched structure analyses in the Neurolucida Explorer software toolbox to quantify the topological parameters (e.g., numbers of dendritic segment in each order, bifurcation nodes, dendritic segments, and terminals) and size-related parameters (e.g., soma size, dendritic length, numbers of intersections, bifurcation nodes and terminals at different distances from the soma). The included angle denotes the widest angle between the two furthest terminals while the soma is the center. The dendrites derived directly from the soma are the first-order branches or primary dendrites. The daughter branches arising from those are second-order branches, and so on. The point at which a dendrite gives rise to two daughter branches is called a bifurcation node. The termination of a dendrite is called a terminal. The dendritic segments between soma and a bifurcation node or two bifurcation nodes are termed internodal segments whereas, the segments between a bifurcation node and terminal are called terminal segments.

Our dendritic spine analyses were based on 22 primary dendritic segments, 28 secondary segments, 33 third order segments and 54 fourth and higher order segments from control and 28 primary dendritic segments, 37 secondary segments, 44 third order segments, and 62 fourth and higher order segments from mutant barrel neurons. We measured the length of the segments and counted spines (all dendritic protrusions on the segments). The density of dendritic spines was determined and expressed as the number of spines per μm for each different order dendritic segment.

2.5 | Statistical analysis

Two-tailed Student’s t-test was applied for statistical evaluation of mean. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. The statistical criterion for significance was p <.05.

3 | RESULTS

3.1 | VSD imaging of the barrel cortex following single whisker stimulation

A previous study in the Bird model mice (the line we used) reported that Mecp2−/y mice have smaller barrels but the whisker-specific barrel patterning can be discerned (Moroto et al., 2013). How does whisker stimulation activate the less defined, smaller barrels in the Mecp2 deficient cortex? We chose VSD imaging to visualize sensory activity in the barrel cortex. Voltage-sensitive dye imaging (VSDi) has been used to image topographic activation of sensory maps in the visual, somatosensory, and auditory cortices in several species ranging from rodents to primates, and it is a reliable measure of spatiotemporal pattern of sensory evoked activity in the neocortex (Grinvald, Omer, Sharon, Vanzetta, & Hildesheim, 2016).

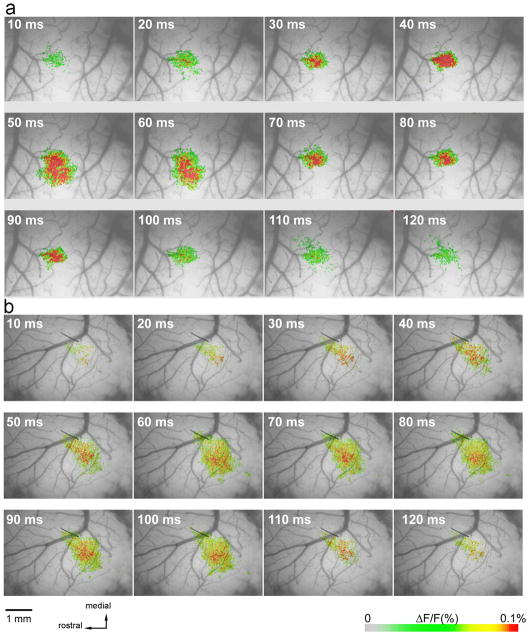

In both mutant and control animals, VSD signal appeared just after the frame when the stimulus was presented and reached its peak 35–45 ms after the stimulus onset, and then decreased and returned to baseline (Figure 1). As noted in the Section 2, we delivered 10 ms duration air puffs (~45 kPA) through the Picospritzer and each puff moved the E2 whisker 1 mm in the dorsoventral direction.

FIGURE 1.

Voltage-sensitive dye optical imaging in the barrel cortex. (a) Pseudocolor maps of E2 whisker stimulation-evoked fluorescence changes in the barrel cortex of a control (C57BL/6, Mecp2+/y) male mouse. The top left corner of each image indicates the time after the stimulus onset. (b) Pseudocolor maps of E2 whisker stimulation-evoked fluorescence changes in the barrel cortex of an exemplary Mecp2−/y mouse. Each frame duration is 5 ms

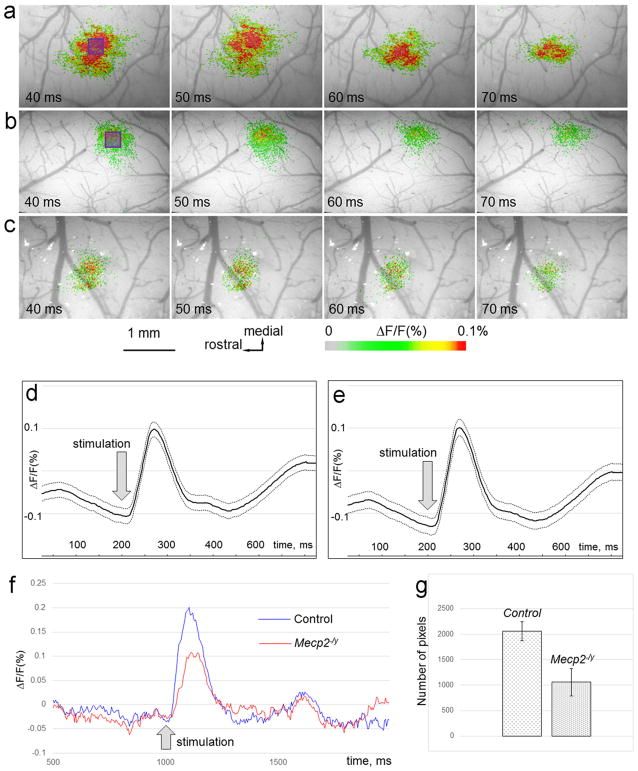

For quantitative analysis, we calculated the number of pixels with the highest value of fluorescence at 40 ms after the stimulus onset. The activated area in the Mecp2−/y mouse barrels had a much less distinct border and was less focalized in comparison to the control barrel cortex. Our results also showed that in Mecp2−/y mice, the numbers of pixels with a fluorescence value above 90% of all the pixels in the imaging area were much lower in Mecp2−/y animals than in control animals (Figure 1). Aside from being weak, optical signals were less focalized in the mutant mice, and the whisker-evoked activity pattern in the mutants is roughly topographic but diffuse with a more irregular shape and less clear border. Obtained VSDi data indicate weakened and less specific whisker-evoked activity in the barrel field of the S1 in Mecp2−/y mice (Figure 2a–c).

FIGURE 2.

Voltage-sensitive dye optical imaging in the barrel cortex during peak of whisker-evoked activity. (a–c) Pseudocolor maps showing single-whisker stimulation fluorescence changes in control (a) and examples from two mutant (b, c) animals during four time points (40–70 ms) around the peak of activation. The time after stimulus onset is indicated at the bottom left corner of each image. (d, e) Time course of the integrated fluorescence signals averaged over 100 trials in one experimental session of control (d) and Mecp2−/y (e) animals. The solid line indicates a moving average of a wave. 2σ indicates the error from this center line. The dotted lines on the graph indicate confidence bounds (center line ± 2σ) against the center line, which represents mean value. (f) Time course of the fluorescence signal calculated from a control (blue) and a mutant (red) animal shown in (a) and (b), respectively. Signals calculated in a small purple square (11 by 11 pixels) shown in (a) and (b). (g) Quantitative analysis of the number of pixels with over threshold value of signal for the Mecp2−/y and control animals (all experiments). Number of pixels with the highest value of fluorescence is calculated at 40 ms after the stimulus onset

We calculated the standard deviation to quantify the variation or dispersion of data set from single imaging sessions with the MiCAM02 imaging system. Standard deviation of 2σ indicated that repeatability of the whisker-evoked response is consistent between the first, the last, and in-between trials for both the control (Figure 2d) and mutant (Figure 2e) cases.

Time course of the response following stimulation was similar between the control and mutant cases but the % change of fluorescence (ΔF/F) was notably different between the two groups (Figure 2f). Quantitative analysis of the number of pixels with the highest value of fluorescence also showed a lower value in Mecp2-y group compared to the control group (Figure 2g).

3.2 | Comparison of TCA terminal arbors

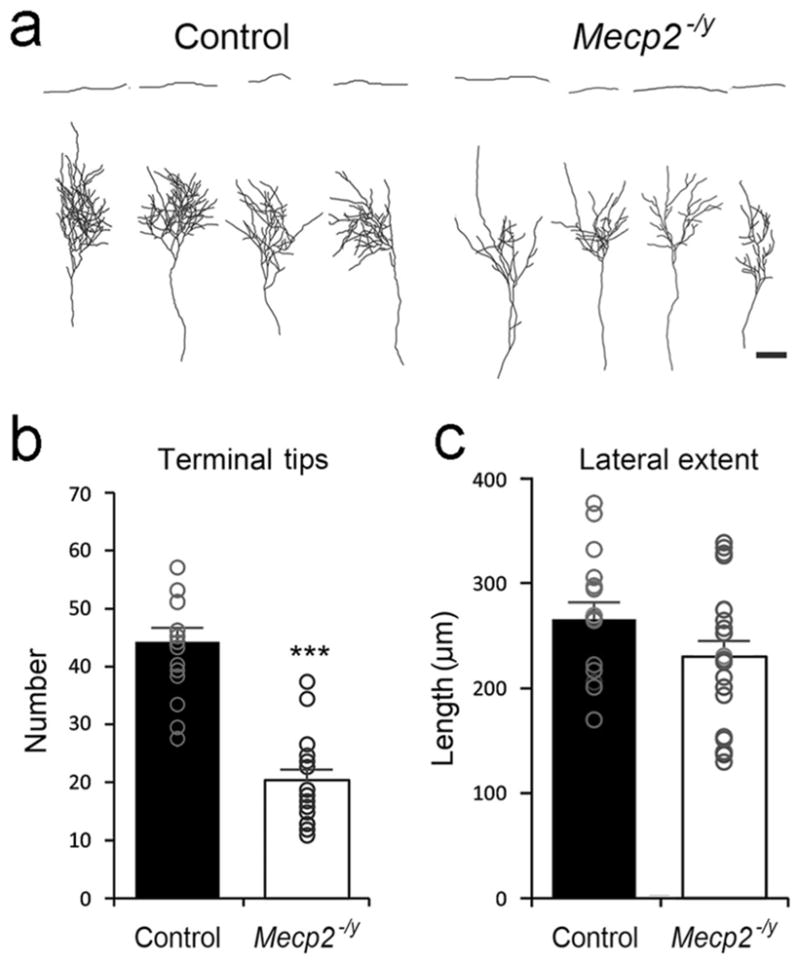

Our functional assays indicated altered neuronal activities in layer IV barrel cortex of Mecp2−/y mice. In the somatosensory system, the TCAs carrying the somatic information, project to the barrel cortex, particularly to the layer IV, and activate the cortical neurons. We asked the question whether the structural features of TCAs and layer IV spiny stellate cell in the barrel cortex of Mecp2−/y mice are also altered. If so, these alterations might be the anatomical basis of functional deficits. To test this hypothesis, we labeled the TCAs by inserting a tiny piece of DiI crystal into the VPM and traced DiI-labeled single TCAs in the barrel cortex (Figure 3a). In both control and Mecp2−/y mice, TCA arbors mainly clustered in layer IV. Compared with the cases collected from control mice, we noted significant decrease in TCA terminal tips in Mecp2−/y mice (Figure 3b), suggesting reduced neurotransmission between TCAs and layer IV neurons. However, TCAs in control and Mecp2−/y mice had comparable lateral extent in the coronal plane (Figure 3c).

FIGURE 3.

Thalamocortical axon (TCA) arbors in control and Mecp2−/y cortex. (a) Single TCAs from control and Mecp2−/y were labeled with DiI and reconstructed. (b) The numbers of axonal terminal tips. (c) The length of the lateral extent of axon arbors. Results are mean ± SEM. Asterisks are used to indicate significant difference between control (n = 16 TCAs from six mice) and Mecp2−/y (n = 22 TCAs from seven mice) groups (***p <.001). Scale bar = 100 μm

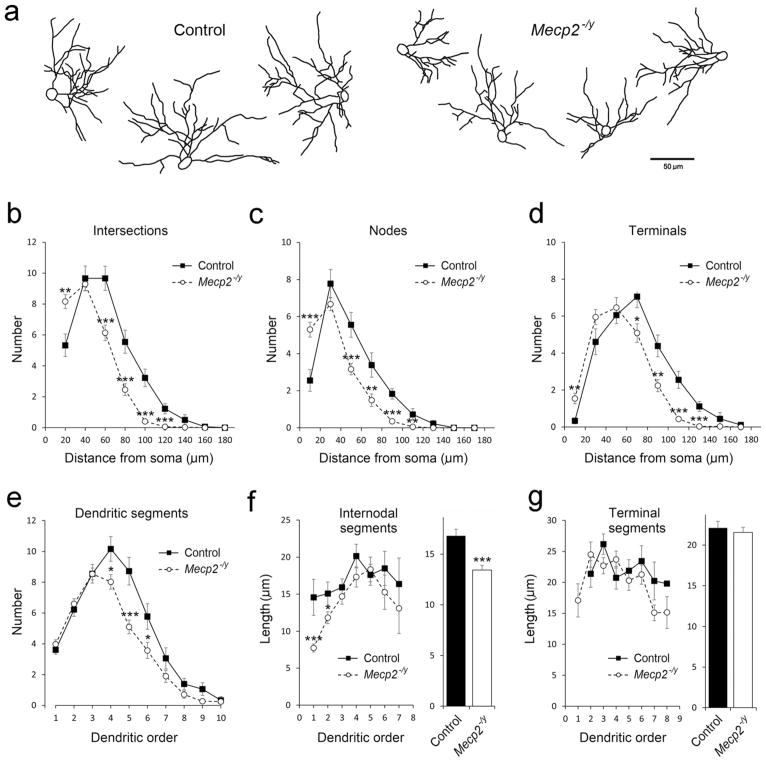

3.4 | Dendritic complexity and spines of stellate cells along the barrel walls

Next, we examined the dendritic complexity of layer IV neurons located along the barrel walls. Golgi-stained spiny stellate cells were collected from control and Mecp2−/y mice and reconstructed for morphometric analyses (Figure 4a). In general, layer IV spiny stellate cells in both genotypes oriented their dendrites toward the barrel hollows. The overall dendritic orientation was comparable between the two groups (Table 1). However, neurons from Mecp2−/y mice had smaller soma size, dendritic arbors, and shorter dendritic length compared to control mice (Table 1). These results are in line with the report that Mecp2−/y mice have smaller barrels while the pattern is still present (Moroto et al., 2013). We evaluated the complexity of dendritic arbors by a series of three-dimensional concentric spheres. We counted the numbers of intersections between the spheres and dendrites (Figure 4b). Neurons in Mecp2−/y mice had fewer number of intersections than those in control mice, except for the proximal region (≤20 μm from the soma). Compared with those in the control group, neurons in Mecp2−/y mice also have fewer bifurcation nodes and terminals, except for the proximal part (Figure 4c,d), resulting in fewer nodes, terminals, and segments in these neurons (Table 1). We also quantified the dendritic segments in each order and found that the numbers of dendritic segments were comparable between the genotypes in lower (1–3) orders. However, in higher (≥4) dendritic orders, the segment number was significantly reduced in neurons of Mecp2−/y mice (Figure 4e). We further measured the length of dendritic segments in different dendritic orders. In neurons of mutant mice, the length of the internodal segments was shorter than those in controls, especially in the first and second order dendrites (Figure 4f). However, the length of the terminal segments was comparable between the two groups (Figure 4g). Our dendritic analyses reveled the abnormal growth and branching of dendrites in layer IV spiny stellate cells in Mecp2−/y mice.

FIGURE 4.

Dendritic features of layer IV spiny stellate cells in the barrel cortex. (a) Golgi-stained layer IV spiny stellate cells from both control (n = 18 neurons from three mice) and Mecp2−/y (n = 37 neurons from three mice) groups were reconstructed, spines are omitted in the illustrations. The complexity of dendritic tress was evaluated by a series of three-dimensional concentric spheres with 20 μm intervals. The numbers of intersections between the spheres and dendrites were counted against the distance from the soma (b). The bifurcation nodes and dendritic terminals were also counted and plotted against the distance from the soma (c) and (d). The numbers of dendritic segments in different dendritic were quantified (e). The length of intermodal segments and terminal segments in different dendritic orders were measured (f and g). Results are mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate significant difference between control and Mecp2−/y mice (*p <.05; **p <.01; ***p <.001)

TABLE 1.

Morphometric features of layer IV spiny stellate neurons in the barrel cortex

| Parameters | Animals | |

|---|---|---|

| Control | Mecp2−/y | |

| Bifurcation nodes | 22.06 ± 1.36 | 17.03 ± 0.77** |

| Terminal tips | 26.83 ± 1.46 | 21.89 ± 0.88** |

| Segments | 48.89 ± 2.80 | 38.92 ± 1.61** |

| Included angle (degree) | 176.65 ± 11.19 | 189.32 ± 9.03 |

| Total dendritic length (μm) | 952.87 ± 59.60 | 692.6 ± 28.26*** |

| Soma area (μm2) | 103.99 ± 3.78 | 93.62 ± 2.29* |

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (Control: n = 18 neurons from three mice, Mecp2−/y: n = 37 neurons from three mice). Asterisks indicate significant differences compared to control mice (*p <.05; **p <.01; ***p <.001).

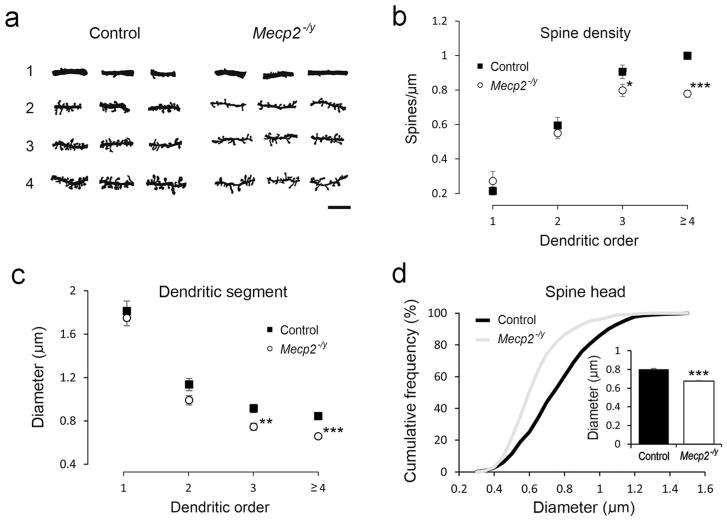

Next, we analyzed the characteristics of dendritic spines in Mecp2−/y mice. Golgi-stained dendritic segments were collected from different dendritic orders (Figure 5a). The spine density in Mecp2−/y mice was significantly reduced in the third and higher order dendrites (Figure 5b). We also measured the diameter of dendritic segments and found that dendritic segments are thinner in neurons from Mecp2−/y mice compared to those from control mice (Figure 5c). Next, we measured the size of spine heads. The diameter of spine head was shorter in Mecp2−/y mice compared to those from control mice (Figure 5d).

FIGURE 5.

Dendritic spines of layer IV spiny stellate cells in the barrel cortex. (a) Examples of dendritic segments of different orders from Golgi-stained layer IV spiny stellate cells in control and Mecp2−/y mice. (b) The density of dendritic spines, measured and plotted against the dendritic order. Measurements of the diameter of dendritic segments (c) and spine head (d). Results are mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate significant difference between control and Mecp2−/y mice (*p <.05; ***p <.001). In (b), the error bars for the fourth and higher order dendritic segments are small and covered by the point marks

4 | DISCUSSION

Genetic manipulations in mice provide useful animal models to probe into cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying various sensorimotor and cognitive phenotypes associated with neurodevelopmental disorders such as RTT. The mouse barrel cortex is also quite amenable to investigate structural and functional sensory deficits related to specific gene mutations. Here, we show that in a mouse model of RTT, Mecp2 null mice, whisker-evoked activity in the barrel cortex is weak and diffuse. This is in agreement with and complementary to the previously reported “weak” barrel patterning in the somatosensory cortex of the Bird line of Mecp2 null mice (Moroto et al., 2013). Further investigations of TCA arbor terminals in postnatal mice and dendritic complexity and spine analyses in young adult mice also indicate that morphological differences most likely pave the way to functional defects.

4.1 | Cortical activity in Mecp2 null mice

Excitation/inhibition (E/I) balance plays an important role in various brain network functions and Mecp2 protein is essential for neuronal maturation and synaptic communication. Previous studies reported impaired E/I balance in CA3 hippocampal pyramidal neurons in Mecp2−/y mice, leading to hyperactive network states and subsequently to seizures (Calfa, Li, Rutherford, & Pozzo-Miller, 2015). In the hippocampus, Mecp2 protein is linked to the regulation of glutamatergic synapses. Such that, loss of the protein causes significant loss of response in glutamatergic synapses and overexpression of the protein enhances the synaptic response (Chao, Zoghbi, & Rosenmund, 2007). In sensory cortex layer V, global loss of Mecp2 shifts the E/I balance in favor of inhibition (Dani et al., 2005). Selective deletion of Mecp2 from cortical excitatory neurons (in Emx1cre; Mecp2flox mice) reduces GABAergic transmission in layer V pyramidal neurons of the prefrontal and somatosensory cortices (Zhang, Peterson, Beyer, Frankel, & Zhang, 2014). Local synaptic circuits in prefrontal cortex layer II/III of Mecp2−/y mice exhibit reduced excitatory activity (Wood & Shepherd, 2010). Loss of Mecp2 from GABAergic neurons in mice have been correlated with some behavioral symptoms of RTT, suggesting that Mecp2 is important for the maturation and normal functioning of the GABAergic circuitry (Chao et al., 2010).

Recently, we examined the E/I balance in layer IV neurons of the barrel cortex in young Mecp2−/y mice. We used whole-cell recordings in thalamocortical slices and found that the E/I balance is altered in favor of inhibition (Lo et al., 2016). Altered E/I balance (Lo et al., 2016), imprecise activation of cortical barrels following whisker stimulation, morphological changes in TCA terminals, and barrel cells (current study) are tempting to speculate that structural and functional alterations in the primary somatosensory cortex may be associated with conspicuous tactile self-stimulation behaviors, such as wringing or kneading the hands, tapping, repeated hand-to-mouth movements, characteristically seen in children with RTT.

4.2 | Loss of Mecp2 function and the barrel cortex

The primary somatosensory cortex is three synapses away from the tactile sensory periphery. Dorsal root and trigeminal ganglion axons convey the tactile sensations to the central nervous system (CNS), where the first synapse occurs in the dorsal column and sensory trigeminal nuclei. Second order neurons project to the contralateral thalamus and synapse with the ventroposterolateral (VPL) neurons for the body and limb-related tactile sensations and the VPM neurons for the orofacial tactile sensations. Both VPL and VPM neurons, in turn project to the layer IV (mostly) of the primary somatosensory cortex. In neuro-developmental disorders, tactile sensory deficits could arise from altered structural or functional characteristics of sensory receptors, neural elements along anywhere in this multisynaptic pathway. In a recent study, Orefice et al. (2016) reported that genetically manipulated mice for various mutations associated with the autism spectrum disorders, including the Mecp2 null mice (Bird model) have tactile sensory dysfunction along the first leg of the pathway. They examined texture discrimination, social behaviors, and electrophysiological properties of low threshold mechanoreceptor afferents in mice with deletion of Mecp2 gene in a region-specific manner, in cortical excitatory neurons, below the cervical cord- and in sensory ganglia. Results of their multipronged approach leads them to the conclusion that defects in primary afferent terminals and their expression of GABAA receptors lead to altered tactile sensitivity.

It is difficult to explain altered E/I balance in the barrel cortex, diffuse VSD responses to whisker stimulation in cortical barrels, altered morphology of TCA terminals and barrel cell dendritic fields solely as a consequence of altered GABAA receptor function and hyper excitability three synapses below the somatosensory cortex. The somatosensory cortical functional and structural alterations we report for the globally Mecp2 function impaired male mice may involve genetic defect imposed constraints at various levels of the trigeminal sensory neuraxis. Investigation of region specific Mecp2 impairment at the level of the trigeminal ganglion, trigeminal brainstem, VPM nucleus, and the barrel cortex may allow sorting out at which level or levels of the system the gene function is required. While such studies will undoubtedly shed light to basic biology of the sensory system development and Mecp2 function, it is important to keep in mind that gene defects in the human nervous system rarely occur in a region-specific manner.

4.3 | Loss of Mecp2 function and morphological defects in thalamocortical circuitry

A number of studies reported altered neuronal structure in Mecp2 mutant mice, with most attention directed to the motor cortex and hippocampus, due to associated phenotypes in RTT. In layer V of the primary motor cortex of Mecp2+/y mice pyramidal neurons reportedly have reduced basal dendritic length, shorter branches, and reduced apical tufts (Stuss, Boyd, Levin, & Delaney, 2012). Reductions in somal size and dendritic complexity have been reported for the callosal projection neurons of layer II/III as well (Kishi & Macklis, 2010).

In this study, VSDi revealed that whisker-evoked sensory activity in the barrel cortex is not as precise and circumscribed as that seen in control cases. This impaired activity pattern is probably due to multiple factors ranging from structural deficits to communication across synapses in thalamocortical and corticocortical circuitry. Our morphological analyses in the barrel cortex of Mecp2−/y mice show that the complexity of TCA arbors is largely reduced, accompanied with the decline of dendritic branching and diameter as well as the decreased spine density and head size. These structural changes in Mecp2−/y mice suggest a reduction of synaptic transmission and information processing. While we do not have direct evidence for this suggestion, it is in line with the results from our VSDi observations.

The whisker barrels, with their distinctive arrangement are present in the SI cortex of Mecp2−/y mice but they are smaller as observed with cytochrome oxidase histochemistry and serotonin transporter immunohistochemistry (Moroto et al., 2013). We observed similar, smaller, and less distinct barrels with VGLUT2 immunohistochemistry, another marker for TCAs (data not shown). So far, no quantification has been done on the neuronal numbers and density in the barrel cortex of Mecp2 null phenotypes. In Golgi-stained material dendritic orientation of layer IV, spiny stellate cells were evident. Dendritic orientation is generally lost when TCA terminals are not patterned or have synaptic release defects (Erzurumlu & Gaspar, 2012). Loss of Mecp2 protein probably does not affect pattern communication from the TCAs to barrel cells.

We intentionally chose cells along the barrel walls with their dendritic fields oriented toward the barrel centers to perform our comparisons between the mutant and control cases. Dendritic tree Sholl analysis showed that Mecp2−/y mice barrel neurons had fewer number of dendritic intersections, fewer bifurcation nodes, and terminals. The numbers of dendritic segments in lower order dendrites were comparable to controls. The reduced branching and internodal segments were most notable in distal dendrites. An older Golgi-Sholl study in the cortex and hippocampus samples from RTT girls also noted shorter length of basal and apical dendrites of pyramidal neurons (Armstrong, Dunn, Antalffy, & Trivedi, 1995). In Mecp2−/y mice, shorter and less branched dendritic arbors, albeit oriented toward barrel centers most likely contribute to the smaller barrel sizes and correlated with the similar phenotype of TCA terminal arbors.

Along with notable decrease in the numbers of dendritic segments distally, we found reduced spine density in distal dendrites. Dendritic spines are perhaps the most active sites of synaptic communication. Decreased spine density and size have been noted in some brain regions of Mecp2 mutant mice, for example, the hippocampal CA1 neurons and layer V pyramidal cells in the motor cortex (Belichenko et al., 2009; Chapleau et al., 2009, 2012; Stuss et al., 2012). Chapleau et al. (2012), however noted that dendritic spine density in CA1 hippocampus stratum radiatum in Mecp2 mutant mice after postnatal day 15 was similar to controls, even though the mutant mice showed characteristic RTT-like symptoms. The distal dendritic protrusions develop later than the proximal dendritic segments. Another possible cause of altered distal dendritic profiles could be the reduction in brain and body weight of Mecp2−/y mice as they get older. These mice show normal physical appearance at the time of birth but impaired development after weaning. Mecp2−/y mice have lighter body weight and shorter lifespan (up to about 8 weeks).

Collectively, our present results from the barrel cortex of Mecp2 mutants confirmed observations in other brain regions and further added to them how structural alterations could be correlated with defective sensory periphery-related activity in the neocortex.

Acknowledgments

Funding information

The Ministry of Science and Technology, ROC, Grant/Award Number: 105-2918-I-002-027; NIH/NINDS, Grant/Award Number: R01 NS092216

Research supported by The Ministry of Science and Technology, ROC 105–2918-I-002-027 (LJL) and NIH/NINDS R01 NS092216 (RSE).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

All authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: RSE and LJL. Acquisition of data: LJL and VT. Analysis and interpretation of data: RSE, LJL, and VT. Drafting of the manuscript: RSE. Study supervision: RSE.

References

- Agmon A, Yang LT, Jones EG, O’Dowd DK. Topological precision in the thalamic projection to neonatal mouse barrel cortex. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:549–561. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00549.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amir RE, Van den Veyver IB, Wan M, Tran CQ, Francke U, Zoghbi HY. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2. Nature Genetics. 1999;23:185–188. doi: 10.1038/13810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong D, Dunn JK, Antalffy B, Trivedi R. Selective dendritic alterations in the cortex of Rett syndrome. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 1995;54:195–201. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199503000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballester-Rosado CJ, Albright MJ, Wu CS, Liao CC, Zhu J, Xu J, Lee LJ, Lu HC. mGluR5 in cortical excitatory neurons exerts both cell-autonomous and -nonautonomous influences on cortical somatosensory circuit formation. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30:16896–16909. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2462-10.2010. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2462-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belichenko PV, Wright EE, Belichenko NP, Masliah E, Li HH, Mobley WC, Francke U. Widespread changes in dendritic and axonal morphology in Mecp2-mutant mouse models of Rett syndrome: Evidence for disruption of neuronal networks. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2009;514:240–258. doi: 10.1002/cne.22009. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.22009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calfa G, Li W, Rutherford JM, Pozzo-Miller L. Excitation/inhibition imbalance and impaired synaptic inhibition in hippocampal area CA3 of Mecp2 knockout mice. Hippocampus. 2015;25:159–168. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22360. https://doi.org/10.1002/hipo.22360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calfa G, Percy AK, Pozzo-Miller L. Experimental models of Rett syndrome based on Mecp2 dysfunction. Experimental Biology and Medicine. 2011;236:3–19. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2010.010261. https://doi.org/10.1258/ebm.2010.010261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao HT, Chen H, Samaco RC, Xue M, Chahrour M, Yoo J, … Zoghbi HY. Dysfunction in GABA signalling mediates autism-like stereotypies and Rett syndrome phenotypes. Nature. 2010;468:263–269. doi: 10.1038/nature09582. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao HT, Zoghbi HY, Rosenmund C. MeCP2 controls excitatory synaptic strength by regulating glutamatergic synapse number. Neuron. 2007;56:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapleau CA, Boggio EM, Calfa G, Percy AK, Giustetto M, Pozzo-Miller L. Hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons of Mecp2 mutant mice show a dendritic spine phenotype only in the presymptomatic stage. Neural Plasticity. 2012;2012:976164. doi: 10.1155/2012/976164. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/976164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapleau CA, Calfa GD, Lane MC, Albertson AJ, Larimore JL, Kudo S, … Pozzo-Miller L. Dendritic spine pathologies in hippocampal pyramidal neurons from Rett syndrome brain and after expression of Rett-associated MECP2 mutations. Neurobiology of Disease. 2009;35:219–233. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.05.001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu YF, Yen CT, Lee LJ. Neonatal whisker clipping alters behavior, neuronal structure and neural activity in adult rats. Behavioral Brain Research. 2013;238:124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.10.022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2012.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani VS, Chang Q, Maffei A, Turrigiano GG, Jaenisch R, Nelson SB. Reduced cortical activity due to a shift in the balance between excitation and inhibition in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:12560–12565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506071102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragich JM, Kim YH, Arnold AP, Schanen NC. Differential distribution of the MeCP2 splice variants in the postnatal mouse brain. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2007;501:526–542. doi: 10.1002/cne.21264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erzurumlu RS, Gaspar P. Development and critical period plasticity of the barrel cortex. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;35:1540–1553. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.08075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferezou I, Bolea S, Petersen CC. Visualizing the cortical representation of whisker touch: Voltage-sensitive dye imaging in freely moving mice. Neuron. 2006;50:617–629. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinvald A, Omer DB, Sharon D, Vanzetta I, Hildesheim R. Voltage-sensitive dye imaging of neocortical activity. Cold Spring Harbor Protocols. 2016;2016(1) doi: 10.1101/pdb.top089367. pdb.top089367. https://doi.org/10.1101/pdb.top089367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy J, Hendrich B, Holmes M, Martin JE, Bird A. A mouse Mecp2-null mutation causes neurological symptoms that mimic Rett syndrome. Nature Genetics. 2001;27:322–326. doi: 10.1038/85899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung BP, Jugloff DG, Zhang G, Logan R, Brown S, Eubanks JH. The expression of methyl CpG binding factor MeCP2 correlates with cellular differentiation in the developing rat brain and in cultured cells. Journal of Neurobiology. 2003;55:86–96. doi: 10.1002/neu.10201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann WE, Johnston MV, Blue ME. MeCP2 expression and function during brain development: Implications for Rett syndrome’s pathogenesis and clinical evolution. Brain and Development. 2005;27(Suppl 1):S77–S87. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishi N, Macklis JD. MECP2 is progressively expressed in post-migratory neurons and is involved in neuronal maturation rather than cell fate decisions. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience. 2004;27:306–321. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishi N, Macklis JD. MECP2 functions largely cell-autonomously, but also non-cell-autonomously, in neuronal maturation and dendritic arborization of cortical pyramidal neurons. Experimental Neurology. 2010;222:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.12.007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee LJ. Neonatal fluoxetine exposure affects the neuronal structure in the somatosensory cortex and somatosensory-related behaviors in adolescent rats. Neurotoxicity Research. 2009;15:212–223. doi: 10.1007/s12640-009-9022-4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12640-009-9022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee LJ, Iwasato T, Itohara S, Erzurumlu RS. Exuberant thalamocortical axon arborization in cortex-specific NMDAR1 knockout mice. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2005;485:280–292. doi: 10.1002/cne.20481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo FS, Blue ME, Erzurumlu RS. Enhancement of postsynaptic GABAA and extrasynaptic NMDA receptor-mediated responses in the barrel cortex of Mecp2-null mice. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2016;115:1298–1306. doi: 10.1152/jn.00944.2015. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00944.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroto M, Nishimura A, Morimoto M, Isoda K, Morita T, Yoshida M, … Hosoi H. Altered somatosensory barrel cortex refinement in the developing brain of Mecp2-null mice. Brain Research. 2013;1537:319–326. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.09.017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2013.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na ES, Nelson ED, Kavalali ET, Monteggia LM. The impact of MeCP2 loss- or gain-of-function on synaptic plasticity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:212–219. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.116. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2012.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orefice LL, Zimmerman AL, Chirila AM, Sleboda SJ, Head JP, Ginty DD. Peripheral mechanosensory neuron dysfunction underlies tactile and behavioral deficits in mouse models of ASDs. Cell. 2016;166:299–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebsam A, Seif I, Gaspar P. Refinement of thalamocortical arbors and emergence of barrel domains in the primary somatosensory cortex: A study of normal and monoamine oxidase a knock-out mice. Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22:8541–8552. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-19-08541.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senft SL, Woolsey TA. Growth of thalamic afferents into mouse barrel cortex. Cerebral Cortex. 1991;1:308–335. doi: 10.1093/cercor/1.4.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuss DP, Boyd JD, Levin DB, Delaney KR. MeCP2 mutation results in compartment-specific reductions in dendritic branching and spine density in layer 5 motor cortical neurons of YFP-H mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31896. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031896. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0031896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A, Lee LJ, Hayashi Y, Muglia L, Itohara S, Erzurumlu RS, Iwasato T. Thalamic adenylyl cyclase 1 is required for barrel formation in the somatosensory cortex. Neuroscience. 2015;290:518–529. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.01.043. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.01.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate P, Skarnes W, Bird A. The methyl-CpG binding protein MeCP2 is essential for embryonic development in the mouse. Nature Genetics. 1996;12:205–208. doi: 10.1038/ng0296-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsytsarev V, Pope D, Pumbo E, Yablonskii A, Hofmann M. Study of the cortical representation of whisker directional deflection using voltage-sensitive dye optical imaging. Neuroimage. 2010;53:233–238. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood L, Shepherd GM. Synaptic circuit abnormalities of motor-frontal layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons in a mutant mouse model of Rett syndrome. Neurobiology of Disease. 2010;38:281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.01.018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolsey TA, Van der Loos H. The structural organization of layer IV in the somatosensory region (SI) of mouse cerebral cortex. The description of a cortical field composed of discrete cytoarchitectonic units. Brain Research. 1970;17:205–242. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(70)90079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Peterson M, Beyer B, Frankel WN, Zhang ZW. Loss of MeCP2 from forebrain excitatory neurons leads to cortical hyperexcitation and seizures. Journal of Neuroscience. 2014;34:2754–2763. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4900-12.2014. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4900-12.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]