Abstract

Sepsis and septic shock are life-threating conditions, which form a continuum of the body's response to overwhelming infection. The current treatment consists of fluid and metabolic resuscitation, hemodynamic and end-organ support, and timely initiation of antibiotics. However, these measures may be ineffective and the sepsis-related mortality toll remains substantial; therefore, an urgent need exists for new therapies. Recently, several nanoparticle (NP) systems have shown excellent protective effects against sepsis in preclinical models, suggesting a potential utility in the management of sepsis and septic shock. These NPs serve as antibacterial agents, provide platforms to immobilize endotoxin adsorbents, interact with inflammatory cells to restore homeostasis and detect biomarkers of sepsis for timely diagnosis. This review discusses the recent developments in NP-based approaches for the treatment of sepsis.

Keywords: : diagnosis, endotoxin, nanoparticles, sepsis, therapy

Sepsis and septic shock are life-threating conditions that describe the continuum of the body's response to overwhelming infection. While the definitions of both are ever-evolving, sepsis has most recently been defined as the body's response to infection that injures its own tissues and organs and septic shock as sepsis accompanied by metabolic derangements and hypotension [1]. Sepsis and septic shock are frequently encountered in the intensive care unit (ICU) [2] and account for 4–17% of ICU admissions in high-income countries [3], 17–26% of hospital mortality [4] and $23.7 billion of hospital expenditure (6.2% of national expenditure in the USA in 2013) [5]. Several therapeutic algorithms against sepsis have been implemented, significantly reducing the sepsis-related mortality over the last few decades. However, the number of deaths from sepsis and septic shock remains substantial, and an urgent need exists for innovative and effective therapies. In this regard, several nanoparticle (NP) platforms have been proposed as potential carriers of antisepsis therapies on the basis of their unique properties, including the small size, functional surface and pharmacokinetic/biodistribution profiles. This review provides a brief summary of sepsis pathophysiology and therapies, and discusses the recent advances in NP-based approaches for the treatment of sepsis and septic shock.

Pathophysiology of sepsis

The etiology of sepsis involves Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria as well as fungal pathogens [6]. When infectious microorganisms invade, the host reacts by mounting complex molecular- and cellular-based immune responses against the pathogens. These pathogens share a group of highly conserved molecules called pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), such as bacterial DNA, sRNA, dsRNA or membrane-forming molecules like lipopolysaccharides (LPS), flagellin, glycosyl phospholipids or peptidoglycans [7]. The host's antigen-presenting cells (APCs) recognize PAMPs via pattern-recognition receptors and present them to T cells. The so-called professional APCs (dendritic cells, macrophages and B cells) present the foreign antigens via the MHC type II (MHC-II) complex, while the nonprofessional APCs (most other cells except erythrocytes) do so via the MHC-I complex. Either presentation results in upregulation of inflammatory gene transcription and release of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1), chemokines (IL-8), reactive oxygen species (ROS), nitric oxide and matrix metalloproteinases [8,9]. These recruit immune cells to the sites of infection in order to fight off the pathogens. Once the infection is under control, inflammatory responses are ultimately resolved via the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines and stress hormones, returning the host immune system to normal homeostasis [9]. In sepsis and septic shock, however, inflammatory responses continue without resolution, causing substantial damages to host tissues. The damaged tissues and necrotic cells elicit the release of endogenous molecular patterns called danger-associated molecular patterns, which are recognized by the pattern recognition receptors in a similar manner as PAMPs [8], and perpetuate the inflammation. Consequently, the host enters a vicious cycle of abnormalities involving hyperinflammation, immunosuppression, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and organ dysfunctions, which are often fatal [10,11].

Prolonged proinflammatory responses lead to immunosuppression, characterized by lymphocyte exhaustion and reprogramming of APCs [12,13]. With the immunosuppression, the host becomes even more vulnerable to additional infections by opportunistic bacteria and Candida spp. [14]. DIC is caused by impairments in the anticoagulation pathway, excess fibrin deposition and low fibrinolytic activities [11]. DIC contributes to the pathophysiology of organ failure by effecting tissue hypoperfusion, reduced oxygen delivery, neutrophil activation and increased tissue injury [11]. Collectively, these phenomena lead to dysfunctions of multiple organs, commonly including lungs (causing acute respiratory distress syndrome), liver (hypoglycemia), kidneys (acute kidney injury) and heart and vessels (circulatory derangements and hypotension) [15].

Treatment of sepsis

Current sepsis therapies focus on early recognition and treatment of infection along with fluid and metabolic resuscitation and end-organ support, including, most commonly, mechanical ventilation and the stabilization of the hemodynamics [2,16]. In addition, several experimental approaches have been tried over the years, resulting in more than 80 Phase II or III clinical trials since 1982 [8]. Clinical trials updated in the past 3 years are summarized in Supplementary Table 1 [17]. These approaches focus on various aspects of sepsis pathophysiology, such as preventing DIC, improving organ functions, modulating immune responses and/or removing causative toxins or pathogens.

Antithrombotic agents

Activated protein C (Drotrecogin-α) was proposed as a complementary antithrombotic agent [18]. Activated protein C was approved by the US FDA in 2001 for the treatment of severe sepsis on the basis of reduced risk of death [18,19] but withdrawn in 2011 because of excessive bleeding and variable clinical outcomes [19,20]. Recombinant soluble thrombomodulin, a cofactor in the thrombin-mediated activation of protein C [21], is currently being tested in a Phase III trial in patients with severe sepsis and coagulopathy [22]. Thrombomodulin showed an improved safety profile due to its indirect mechanism of action [23].

Immunomodulatory agents

Corticosteroids such as methylprednisolone, dexamethasone and hydrocortisone have long been used to suppress inflammation [8]. They inhibit several proinflammatory signaling pathways and have been effective in various conditions, such as asthma and rheumatoid arthritis [24], where inflammation is an important component. However, their therapeutic effects in septic shock remain inconclusive [25].

Since the adaptive immune system is significantly damaged after prolonged hyperinflammation, immune stimulating cytokines and antibodies are proposed as a way of reversing immune suppression [10]. For example, IL-7, IL-15 and anti-programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and PD-1 ligand (PD-L1) antibodies have shown positive results in reversing T-cell dysfunction [26]. IL-7 increases differentiation, survival and proliferation of T cells, and helps maintain T-cell homeostasis. IL-7 improved the survival in the cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) mouse model [27] and in the 2-hit model of sublethal CLP followed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia [28]. IL-7 has shown an improved safety profile relative to other immune-stimulating agents in HIV and cancer patients [26]. Anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 antibodies have been widely studied in cancer therapy, resulting in several FDA-approved products [29,30]. These antibodies have reversed sepsis-induced immunosuppression and improved survival in mouse models of fungal sepsis [31].

Antioxidants

Vitamin C is a potent antioxidant and an essential cofactor for iron and copper-containing enzymes [32,33]. It is expected to bring several benefits in sepsis treatment as it helps preserve endothelial function and microcirculatory flow and synergize the glucocorticoid function by preventing oxidation of the glucocorticoid receptor [33]. In addition, administration of high-dose vitamin C resulted in decreased vasopressor requirement and overall duration of treatment in postsurgical patients with septic shock [34]. Vitamin C is currently tested in Phase II and III clinical trials in patients with sepsis and septic shock [35]. A recent study reported that vitamin C was particularly effective in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock when combined with hydrocortisone and thiamine. This combination prevented the progression of organ dysfunction and reduced the mortality from 40.4 to 8.5% [33].

Endotoxin antagonists

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), or endotoxin, a component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, represents a major type of PAMPs and triggers the physiologic derangements seen in Gram-negative sepsis [10]. LPS thus makes an important target in sepsis treatment. Since the first effort to use polyclonal antibody against LPS in 1982 [36], various endotoxin antagonists have been studied.

Lipoproteins constitute an example of natural LPS adsorbents. When circulating LPS binds to lipoproteins, it is sequestered in the lipoprotein micelle and slowly removed via hepatocytes with minimal activation of macrophages, monocytes and other LPS-responsive cells [37]. Synthetic LPS antagonists that can bind to LPS via electrostatic and/or hydrophobic interactions, such as cationic peptide amphiphiles [38,39] or cationic small molecules [40–42], have also been explored. However, their effectiveness as anti-LPS therapies is hampered by systemic toxicity and/or nonspecific protein binding [43]. For example, polymyxin B (PMB), an amphiphilic polycationic peptide and one of the most effective neutralizers of LPS, is unsuitable for systemic administration due to its significant nephro- and neurotoxicity [44,45].

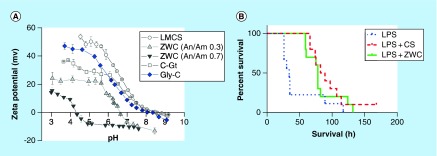

Chitosan, a linear copolymer of D-glucosamine and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine produced by partial deacetylation of chitin [46], has gained attention as a safe pharmaceutical excipient for a wide range of biomedical applications [47]. Chitosan is known to have antimicrobial ability [48]; however, its parenteral use has been limited due to the poor water solubility at the physiological pH [49]. To overcome this, a water-soluble chitosan derivative (zwitterionic chitosan [ZWC]) was produced by partial succinylation of chitosan [50,51]. ZWC is negatively charged and water soluble at the physiological pH and positively charged in acidic pH (Figure 1A). When conjugated on cationic NP surface, ZWC neutralized the charge and reduced their toxicity to normal cells [52]. On poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) NPs, ZWC formed a hydrophilic layer that played a similar role as polyethylene glycol (PEG) in preventing the interaction with macrophages [53]. Interestingly, ZWC suppressed the production of MIP-2 and TNF-α from the LPS-challenged macrophages [51] and extended the survival of mice with LPS-induced sepsis (Figure 1B) [54]. When administered orally as a prophylactic measure, ZWC reached the colon with minimal gastrointestinal absorption and provided a local anti-inflammatory effect in mice with chemically induced colitis [55].

Figure 1. . Charge profile and anti-inflammatory effect of zwitterionic chitosan.

(A) pH-dependent zeta-potential profiles of unmodified LMCS and ZWC derivatives prepared with different An/Am ratios, C-Gt and Gly-C. (B) C57BL/6 mice were injected intraperitoneally with LPS (20 mg/kg) and treatments (CS or ZWC, 800 mg/kg). n = 9 (LPS); n = 10 (CS, ZWC).

An/Am: Anhydride to amine; C-Gt: Chitosan glutamate; CS: Chitosan; Gly-C: Glycol chitosan; LMCS: Low-molecular-weight chitosan; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; ZWC: Zwitterionic chitosan.

(A) Reprinted with permission from [51] © Public Library of Science (2012).

(B) Reprinted with permission from [54] © Springer Nature (2016).

NPs as a potential platform for sepsis treatment

In recent years, NPs have been proposed as carriers of sepsis diagnostics and treatments. Small-molecule drugs tend to distribute throughout the body, cause undesirable side effects and undergo rapid renal clearance with a limited residence time in the body [56,57]. NPs with an optimal surface, composition and size have a longer circulation half-life and differential biodistribution profile compared with the free drug counterpart [58,59]. Therefore, NPs can afford the time and exposure to neutralize PAMPs in the blood and at the sites of infection. In addition, NPs help disperse poorly soluble drugs in the aqueous medium and increase their bioavailability. With large surface area-to-volume ratios, NPs’ surfaces can also be functionalized with multiple copies of ligands to interact with a specific type of cells. Several approaches take advantage of these features of NP systems for the prevention and treatment of sepsis (Table 1). The following section discusses recent advances in NP-based sepsis therapy.

Table 1. . Preclinical studies of nanoparticle-based sepsis therapy.

| NP | Animal model | Sample size (per treatment) | Dose | Administration route | Mechanism of action | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNAPPs | Mouse peritonitis | n = 5 | 8.3 mg/kg | IP | Antibacterial | [60] |

| Ceria-zirconia NPs | CLP | n = 5 | 2 mg/kg | IP | Antioxidant | [61] |

| Piceatannol-loaded albumin NPs | LPS-induced inflammation | n = 3 | 4.3 mg/kg | IV infusion | Anti-inflammatory | [62] |

| Sialic acid-decorated NPs | CLP | n = 8 n = 12 |

2 mg/kg 20 μg/kg |

IP Intratracheal |

Anti-inflammatory | [63] |

| Exosomes containing MFGE8 | CLP | n = 18 | 20 μg/kg | IV infusion | Promote clearance of apoptotic cells | [64] |

| Exosomes delivering miR-223 | CLP | n = 8 | 2 mg/kg | IV | Anti-inflammatory | [65] |

| RBC-coated NPs | α-toxin challenged | n = 9 | 80 mg/kg | IV | α-toxin antagonist | [66] |

| Macrophage-coated NPs | Mouse bacteremia | n = 10 | 300 mg/kg | IP | Endotoxin antagonist | [67] |

| Liposomes | S. aureus mouse bacteremia | n = 10 | 100–400 mg/kg | IV | Exotoxin antagonist | [68] |

| Opsonin-bound magnetic nanobead | Mouse bacteremia | n = 6 | Continuous perfusion | Extracorporeal blood cleansing | [69] | |

CLP: Cecal ligation and puncture; IP: Intraperitoneal; IV: Intravenous; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; NP: Nanoparticle; RBC: Red blood cell; SNAPP: Structurally nanoengineered antimicrobial peptide polymer.

Antibacterial or antioxidant NPs

Silver (Ag) engineered as nanoscale particles has been explored as an antimicrobial agent [70]. Metallic Ag NPs may accumulate in the bacterial membrane to cause damage or generate ROS to induce toxicity [71]. In addition, Ag NPs serve as a reservoir of Ag+ ions, which form irreversible adducts with cellular components (DNA, peptides, cofactors or enzymes) to inactivate a broad spectrum of bacteria [71]. The shape of Ag NPs plays a significant role in their interactions with the bacterial membranes [72]. Antibacterial activity also varies with the NP size, because the size affects the mobility of NPs and the dissolution rate of Ag+ ions. Ag is known to have minimal risk in human and eliminated by the liver and kidneys [73]. However, the long-term safety of systemically administered Ag remains to be determined.

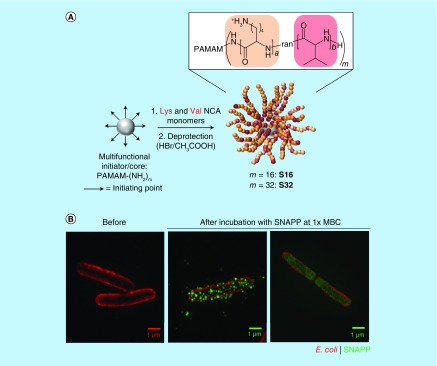

A new type of antimicrobial agents, called ‘structurally nanoengineered antimicrobial peptide polymers’ (SNAPPs), were recently reported [60]. The polymer is synthesized by the ring-opening polymerization of lysine and valine N-carboxyanhydrides at the amine termini of poly(amidoamine) (PAMAM) dendrimers and makes star-shaped unimolecular NPs with potent antimicrobial activities (Figure 2A) [60]. SNAPPs demonstrated sub-μM activity against a broad range of bacteria including multidrug-resistant pathogens, due to the high local concentration of cationic peptides afforded by the NP architecture. SNAPPs developed no resistance in colistin- and multidrug-resistant bacteria, likely owing to the multimodal antimicrobial mechanism (destabilization of the outer and cytoplasmic membranes (Figure 2B) and induction of apoptosis-like death). Despite the cationic charges, SNAPPs showed negligible hemolytic activity and cytotoxicity to mammalian cells at concentrations far greater than bactericidal levels. In a mouse model of peritonitis induced by colistin- and multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, SNAPPs showed significantly better antibacterial activities than a traditional antibiotic (imipenem) [60].

Figure 2. . Structurally nanoengineered antimicrobial peptide polymers, a synthetic antimicrobial nanoparticle.

(A) Synthesis of SNAPPs via ring-opening polymerization of lysine and valine NCAs was initiated from the terminal amines of PAMAM dendrimers. Second- and third-generation PAMAM dendrimers with 16 and 32 peripheral primary amines were used to prepare 16- and 32-arm SNAPPs, respectively. The number of repeat units for lysine and valine are (A) and (B), respectively. (B) 3D-structured illumination microscopy images of Escherichia coli before and after incubation with AF488-labeled SNAPP at 1× minimum bactericidal concentration. Scale bars, 1 μm. E. coli: red; SNAPP: green.

NCA: N-carboxyanhydride; PAMAM: Poly(amidoamine); SNAPP: Structurally nanoengineered antimicrobial peptide polymer.

Reprinted with permission from [60] © Springer Nature (2016).

Ceria (Ce) NPs are shown to have antioxidant activities [74,75]. A high ratio of Ce3+/Ce4+ is desirable for an effective ROS scavenging effect, but the reduction of Ce4+ to Ce3+ is energetically unfavorable [61]. This challenge was addressed by incorporating Zr4+, which facilitated the release of the lattice strain during the conversion due to the small size of Zr4+ relative to Ce4+. Ce-Zr NPs with an optimal atomic ratio (Ce0.7Zr0.3O2) exhibited a greater ROS-scavenging activity and anti-inflammatory effect than Ce NPs. Ce-Zr NPs showed a significant protective effect and saved 100% of animals in an LPS-induced endotoxemia rat model, while the unprotected control group showed 60% mortality [61]. In a more aggressive CLP model, Ce-Zr NPs showed significant anti-inflammatory effects, manifested by reduced tissue infiltration of monocytic phagocytes and signs of multiorgan dysfunction, and a longer survival time relative to the control group. The sustained antioxidant activity based on constant release of Ce3+ has been noted as a unique advantage of the Ce-Zr NPs [61].

Diagnostic NPs

Gold (Au) NPs serve as excellent diagnostic biological sensors based on localized surface plasmon resonance [76], an optical phenomenon generated by a light wave trapped in the conducive NPs smaller than the wavelength of the light [77]. Surface plasmons confined in Au NPs generate a distinct extinction peak in the visible spectrum, which shifts upon aggregation [78]. This property has been utilized in the detection of circulating phospholipase A2 (PLA2) [79], an enzyme catalyzing the formation of inflammatory lipid mediators, the concentration and the activity of which increase during sepsis [80]. Here, unilamellar liposomes are loaded with biotinylated multiarm PEG as a substrate and polystreptavidin-coated Au NPs as a detection agent [79]. PLA2 in blood sample, when mixed with the liposomes, causes enzymatic cleavage of phospholipids and release of the biotinylated multiarm PEG, which reacts with polystreptavidin-coated Au NPs to form a multivalent NP network. This network adheres to a line of streptavidin on a test strip via biotin-streptavidin interaction, making a red signal that can be detected without a visual aid. This method detects 1-nM human PLA2 in serum in 10 min.

Immune-modulating NPs

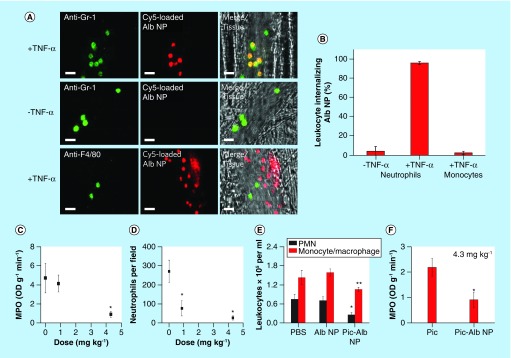

To address endothelial inflammation, bovine serum albumin NPs were used as carriers of piceatannol, a spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitor [62]. The albumin NPs (100 nm), made by ethanol precipitation and glutaraldehyde cross-linking, were readily taken up by neutrophils adherent to the inflamed endothelial cells via Fcγ receptors but not by resting neutrophils or other adherent cells (Figure 3A & B). Albumin NPs delivered piceatannol to inhibit spleen tyrosine kinase-mediated β2 integrin signaling [81], thereby reversing the TNF-α-activated adhesion of neutrophils. In a mouse model of LPS-induced lung inflammation, which mimics acute lung injury associated with sepsis, the piceatannol-loaded albumin NPs significantly reduced the adhesion of neutrophils as well as lung tissue myeloperoxidase activity, an indicator of neutrophil sequestration (Figure 3C & D). The drug loaded in albumin NPs reduced infiltration of neutrophils and monocytes to the lungs (Figure 3E). The NP-loaded piceatannol was more effective than a free drug in myeloperoxidase reduction (Figure 3F), due to the preferential uptake of NPs by activated neutrophils [62]. These results demonstrate how targeted NPs can outperform a free drug in addressing inflammatory cells responsible for tissue injury.

Figure 3. . (A & B) Uptake of albumin nanoparticles by adherent neutrophils in venules, and (C–F) effects of piceatannol-loaded albumin NPs on LPS-induced lung inflammation.

(A) Cy5-loaded albumin NPs (red) are internalized by activated neutrophils (labeled with anti-Gr-1, green) following intrascrotal injection of TNF-α (+TNF-α) or during surgical stress-induced vascular inflammation (-TNF-α) in mice. Monocytes (labeled with anti-F4/80, green) 3 h following TNF-α-induced vascular inflammation (+TNF-α). Scale bars, 20 μm. (B) Percentage of neutrophils and monocytes internalizing albumin NPs. (C) Lung MPO activity and (D) number of neutrophils sequestered in lungs, after intravenous infusion of piceatannol-loaded albumin NPs. (E) Leukocyte number in bronchoalveolar lavage after intravenous infusion of Alb NPs and Pic-Alb NPs with piceatannol amount at 4.3 mg/kg. (F) Neutrophil infiltration in LPS-induced acute lung inflammation assessed by MPO activity after intravenous infusion of free Pic and Pic-Alb NP at 4.3 mg/kg.

Alb NP: Albumin nanoparticle; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; MPO: Myeloperoxidase; NP: Nanoparticle; Pic: Piceatannol; Pic-Alb NP: Piceatannol-loaded albumin NP.

Reprinted with permission from [62] © Springer Nature (2014).

Sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectins (Siglecs) are prevalent on hematopoietic cells and, when bound to the ligand (sialic acid), downregulate acute inflammatory responses by inhibiting Toll-like receptor signaling [82]. PLGA NPs decorated with N-acetylneuraminic acid (NANA), a sialic acid, (NANA-NP) were produced to target activated macrophages [63]. NANA-NP induced oligomerization of Siglecs on macrophages via multivalent binding and was superior to free NANA in attenuating proinflammatory cytokine production from LPS-challenged macrophages. NANA-NP reduced inflammatory effects in mouse models of systemic inflammation, including the CLP model of polymicrobial sepsis and localized lung injury, and extended the survival of animals significantly longer than free NANA or bare NPs. Given that NANA-NP binding to Siglecs augments the expression of IL-10, which in turn stimulates Siglec production, it is thought that NANA-NP amplifies negative feedback pathway to return the inflamed macrophages to homeostasis. Importantly, NANA-NP had similar anti-inflammatory effects in human macrophages and monocytes and a human ex vivo lung perfusion model, showing the potential for clinical translation [63]. This study demonstrates that NPs serve as promising platforms for conjugating ligands that downregulate proinflammatory immune cells.

Recently, nanovesicles of natural origin called exosomes have gained interest for the diagnosis and therapy of sepsis [83,84]. Exosomes are secreted by various mammalian cells to shuttle a specific set of functional RNAs and proteins between cells [84–87]. Carrying a series of miRNAs produced or dysregulated during the proinflammatory signal transduction [88,89], exosomes are considered potentially useful biomarkers of sepsis for diagnosis and monitoring. For example, exosomes isolated from mice that had undergone CLP showed significant increase in the levels of miR-16, miR-17, miR-20a, miR-20b, miR-26a and miR-26b [90]. Exosomes remain relatively stable in circulation and protect the miRNA cargos during isolation, thus serving as reliable biomarkers [83]. Exosomes also carry miRNAs and proteins that modulate immune responses. Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) release exosomes containing miR-146a that downregulates inflammatory gene expression. When administered as a prophylactic measure to LPS-challenged mice, miR-146a-containing exosomes reduced the TNF-α and IL-6 production as compared with miR-146a-deficient exosomes [91]. To a similar effect, immature dendritic cells release exosomes containing milk fat globule EGF factor VIII (MFGE8), a protein that is required to opsonize apoptotic cells for phagocytic removal but is suppressed in septic animals [64]. Upon the administration of MFGE8-containing exosomes, CLP-challenged rats restored the ability to clear apoptotic cells and prevent their secondary necrosis, showing a higher survival rate (87.5%) than no treatment control (37.5%). Similarly, exosomal miR-223 released by mesenchymal stem cells downregulated the production of proinflammatory cytokines, reduced cardiac injury and prolonged the survival of CLP-challenged mice [65]. However, given the complex roles of exosomal contents, therapeutic use of exosomes requires a careful characterization and understanding of the biology. Some exosomes can rather aggravate the disease progression. For example, BMDC-derived exosomes also carry miR155 that promotes endotoxin-induced proinflammatory gene expression and exacerbates the response to LPS in vivo [91]. Platelet-derived exosomes contain p22phox and gp91phox subunits of NADPH oxidase, which causes vascular cell damage through the production of ROS. The platelet-derived exosomes, incubated with endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells, induced significant ROS generation and apoptotic cell death [86].

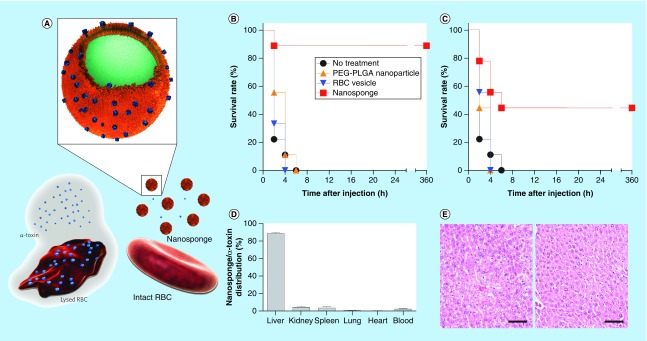

NPs as an antagonist to toxins

Zhang and colleagues have proposed to modify the surface of PLGA NPs with red blood cell (RBC) membrane for extending the circulation half-life of the NPs as drug carriers [92]. Subsequently, it was discovered that the RBC membrane-cloaked NPs (RBC-NPs) could capture circulating toxins and interfered with toxins’ virulence effect on host systems (Figure 4A) [66,93]. The RBC-NPs were produced by extruding approximately 80-nm PLGA NPs with RBC membrane-derived vesicles through a porous membrane [92]. The RBC-NPs interact with different types of pore-forming toxins in a similar manner as host cells via membrane-bound proteins, lipid derivatives, cholesterol and electrostatic interactions [93]. Here, the PLGA NPs serve as solid platforms to orient the membrane in a right direction [94] and prevent the fusion of RBC membrane with cells and subsequent cell damage [66]. The RBC-NPs adsorb membrane-damaging toxins and spare toxins’ cellular targets such as RBC, protecting α-toxin-challenged mice significantly better than PEGylated PLGA NPs or RBC vesicles without NP core (Figure 4B & C) [66]. The toxin-bound NPs did not escape the typical fate of NPs and accumulated primarily in the liver (Figure 4D) [66]. Nevertheless, the lack of liver tissue damage indicates that captured toxins were safely metabolized by hepatic macrophages (Figure 4E) [66]. Recently, PLGA NPs were coated with cell membrane derived from J774 mouse macrophages to act as a macrophage decoy that intercepts circulating endotoxins [67]. In addition, the macrophage-like NPs sequestered proinflammatory cytokines to prevent the downstream inflammation cascade. In a mouse Escherichia coli bacteremia model, the macrophage-coated NPs reduced the proinflammatory cytokine levels, inhibited bacterial dissemination and prolonged the survival of animals with a single dose [67].

Figure 4. . Red blood cell (RBC) membrane-cloaked PLGA NPs as a toxin antagonist.

(A) Schematic structure of toxin nanosponges (RBC-NPs) and their mechanism of neutralizing PFTs. RBC-NPs consist of substrate-supported RBC bilayer membranes into which PFTs can incorporate. After being absorbed and arrested by the RBC-NPs, the PFTs are diverted away from their cellular targets, thereby avoiding target cells and preventing toxin-mediated hemolysis. (B & C) Survival rates of mice over 15 days following an intravenous injection of α-toxin (75 μg/kg). RBC-NPs (80 mg/kg), RBC vesicles or PEG–PLGA NPs were administered intravenously 2 min (B) before or (C) after the toxin injection. (D) Biodistribution of α-toxin-bound nanosponges 24 h after intravenous injection. (E) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained liver histology showed no tissue damage on day 3 (left) and day 7 (right) following α-toxin-bound nanosponge injections (scale bars, 100 μm).

PEG–PLGA NP: Polyethylene glycol–poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticle; PFT: Pore-forming toxin; RBC-NP: Red blood cell membrane-cloaked nanoparticle.

Reprinted with permission from [66] © Springer Nature (2013).

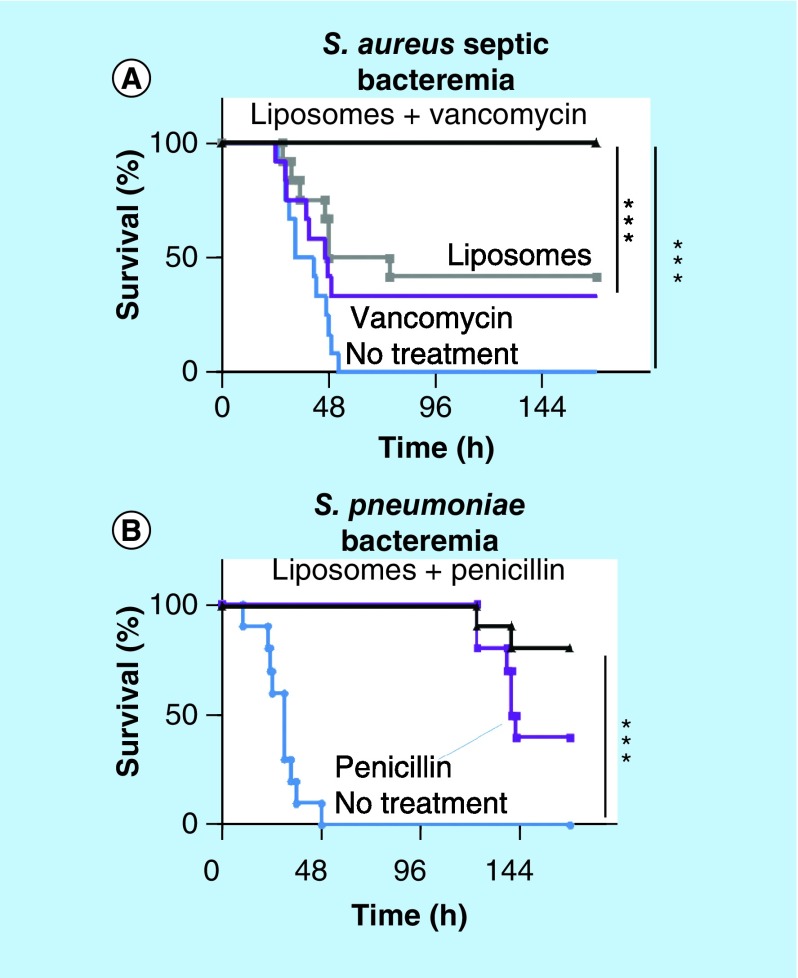

With a similar rationale as the RBC-NPs, artificial liposomes were engineered as a decoy cell to sequester bacterial exotoxins [68]. The liposomes comprised cholesterol and sphingomyelin, which were critical to the mimicry of animal cells, thereby neutralizing toxins. The engineered liposomes protected epithelial HEK 293 cells and human umbilical vein endothelial cells from toxin-induced lysis and inflammatory activation. In mouse models of invasive pneumococcal pneumonia and fatal pneumococcal sepsis, these liposomes significantly improved the survival rate and reduced TNF-α levels and bacterial load in blood and lung as compared with the untreated control group. In addition, animals with lethal Staphylococcus aureus sepsis survived in a dose-dependent manner when treated with the liposomes within 10 h after injection. The liposomes themselves did not kill circulating bacteria nor activate neutrophils to induce nitric oxide and ROS and mediate the killing, suggesting that the antibacterial activities were mainly due to the protection of host immune cells from toxin-induced lysis. The toxin sequestration approach was combined with vancomycin to provide complete protection from systemic S. aureus infection and improve the survival rate of animals with fatal Streptococcus pneumoniae-induced sepsis (Figure 5) [68].

Figure 5. . A combination of toxin-sequestration with antibiotic treatment to treat fatal Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae infections.

(A) Mice infected intravenously with the septic S. aureus strain and administered with injections of PBS as control, liposomes (2, 6 and 24 h after infection, total dose: 37.5 mg/kg), 100 mg/kg of vancomycin (1 and 9 h after infection) or liposomes and vancomycin. (B) Mice infected intravenously with S. pneumoniae D39 and administered with injections of PBS as control, 25 mg/kg of penicillin (10 and 24 h after infection), 100 mg/kg liposomes and 25 mg/kg of penicillin (10 and 24 h postinfection).

PBS: Phosphate-buffered saline.

Reprinted with permission from [68] © Springer Nature (2014).

NPs for extracorporeal blood cleansing

As a cyclic cationic antibiotic with both lipophilic and hydrophilic groups, PMB has high affinity for LPS and can neutralize its toxicity [43,44]. However, due to the side effects, such as nephrotoxicity and neurotoxicity, PMB is used for extracorporeal therapy. For example, PMB was immobilized to polystyrene fibers in a hemoperfusion device to capture LPS in the blood [95,96]. Similarly, a microfluidic device utilizing a magnetic external field has been developed for the removal of pathogens from contaminated blood. For example, PMB-bound cobalt/iron nanomagnets [97] and zinc-coordinated bis(dipicolylamine) magnetic particles [98] were used to capture endotoxins in blood and were removed from the blood by magnetic field.

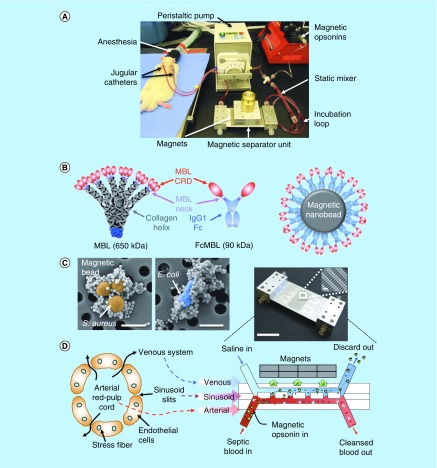

Kang et al. designed a unique microfluidics device with a flow channel design, inspired by the microarchitecture of the spleen, for extracorporeal blood cleansing (Figure 6A) [69]. Magnetic nanobeads (128 nm) were coated with an engineered human opsonin (Figure 6B) to capture a broad range of pathogens and toxins (Figure 6C). The engineered opsonin contained a carbohydrate recognition domain derived from native mannose-binding lectin for interaction with pathogens and toxins. The other end of the opsonin was biotinylated, so that it could bind to the streptavidin-coated nanobead surface allowing the carbohydrate recognition domain to face outward (Figure 6B). The mixture of septic blood and nanobeads was passed through an arterial channel of the device, above which stationary magnets separated the pathogen-bound magnetic nanobeads from the blood, returning the cleansed blood to the host (Figure 6D). Small nanobeads (128 nm) were desirable for capturing toxins and bacteria due to the large surface area per volume but disadvantaged with respect to magnetic moments, which was addressed by adding larger beads (1 μm) as local magnetic field gradient concentrators. This device removed more than 90% of multiple Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, fungi and endotoxins from whole blood at a flow rate of up to 1.25 l/h in vitro. With septic rats, this device removed 90% of live S. aureus and E. coli in the blood within 1 h and reduced the level of inflammatory cytokines as well as inflammatory cell infiltrate and interstitial edema in major organs. 89% of endotoxemic rats receiving the cleansing survived the 5-h experiment with better respiratory rate and temperature than the untreated animals, which showed 86% mortality in the same period.

Figure 6. . Magnetic opsonin and biospleen device.

(A) Photograph of the experimental animal setup for extracorporeal blood cleansing. (B) Design scheme for genetic engineering of native MBL to produce the generic opsonin FcMBL and coat it on magnetic nanobeads (128 nm) to produce magnetic opsonins. (C) Pseudocolored scanning electron micrographs showing multiple opsonin-coated magnetic beads (128 nm) bound to the bacteria S. aureus (orange/brown; left) and E. coli (blue; right). Scale bars, 1 μm; arrows indicate pathogen with bound beads. (D) Schematics of a venous sinus in the red pulp of the spleen (left) and a longitudinal view of the biospleen (right), with a photograph of an engineered device (top right).

MBL: Mannose-binding lectin.

Reprinted with permission from [69] © Springer Nature (2014).

In a recent study, magnetic NPs were decorated with aptamers and photosensitizers to detect and remove pathogens [99]. Here, poly(allylamine)-coated iron oxide magnetic NPs were functionalized with chlorin e6 (Ce6) and bacteria-specific aptamers by carbodiimde chemistry and stabilized with PEG. The dual-functionalized iron oxide NPs (IO-Ce6-Apt) adhered to S. aureus in blood via aptamers. The IO-Ce6-Apt-bound S. aureus were separated from the blood by external magnet, allowing for fast and sensitive detection. Moreover, the IO-Ce6-Apt-bound S. aureus were effectively eradicated by laser irradiation due to the photodynamic effect of Ce6. The blood disinfected by magnetic removal and photodynamic killing could be transfused to mice without causing systemic infection, demonstrating the efficiency of two-step cleansing process.

Conclusion & future perspective

Several recently described NP systems have demonstrated excellent therapeutic activities in preclinical models of sepsis. NPs may serve as antibacterial agents, provide platforms to immobilize adsorbents that capture circulating endotoxins, interact with inflammatory immune cells to restore homeostasis and detect biomarkers of sepsis to reveal the status of patients. NPs accommodate these functionalities via their small size, large surface area per volume, unique optical properties and various material compositions. Moreover, NPs with an optimal size and surface chemistry can circulate a prolonged period to afford enough time to capture toxins in the blood. A wealth of NP technologies is available in the nanomedicine community, with the main application aiming at cancer therapy and diagnostics. The nanomedicine field has a limited experience in applying NP technologies to prevention and treatment of sepsis. Therefore, it is a prime time for nanomedicine researchers to explore new opportunities in this critical disorder. Most NP-based sepsis therapies are in the early stage of development, and their limitations and challenges are yet to be defined. Due to the abnormal hemodynamics, circulating NPs may show different pharmacokinetics/biodistribution profiles in septic subjects than those predicted from healthy subjects. Given the rapid progress of the disease, NPs may have a narrow window of time for effective application. Animal models that can recapitulate the progression of hemodynamic and metabolic phases of human disease and sensitive biomarkers for staging patients will be critical to the successful application of NPs in sepsis treatment.

Executive summary.

Pathophysiology of sepsis

Sepsis is a systemic inflammatory response syndrome, caused by dysregulated host responses to microbial infection.

When the excessive inflammatory responses are not properly managed, the host experiences a vicious cycle of abnormalities involving hyperinflammation, immunosuppression, disseminated intravascular coagulation and organ dysfunctions, which are often fatal.

Current & experimental treatments of sepsis

The current sepsis therapy focuses on early recognition and treatment of infection along with ventilatory, metabolic and hemodynamic support.

Experimental approaches focus on preventing disseminated intravascular coagulation, improving organ functions, modulating immune responses and/or removing the causative toxins and pathogens.

Nanoparticles as a potential platform for sepsis treatment

Nanoparticles have small size, large surface area-to-volume ratio, unique optical properties and various material compositions.

The above features allow the nanoparticles to serve as antibacterial agents, provide platforms to immobilize adsorbents that capture circulating endotoxins, interact with inflammatory immune cells to restore homeostasis and detect biomarkers of sepsis to reveal the status of patients.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplementary data

To view the supplementary data that accompany this paper, please visit the journal website at: www.future-science.com/doi/full/10.4155/tde-2018-0009

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This research was supported by the NIH R21 AI119479 and student supports for SA Yuk (Graduate Assistance in Areas of National Need Fellowship) and DA Sanchez-Rodriguez (Undergraduate Research Experience Purdue – Columbia Scholarship). The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest; •• of considerable interest

- 1.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315(8):801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(3):304–377. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4683-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Esteban A, Frutos-Vivar F, Ferguson ND, et al. Sepsis incidence and outcome: contrasting the intensive care unit with the hospital ward. Crit. Care Med. 2007;35(5):1284–1289. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000260960.94300.DE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fleischmann C, Scherag A, Adhikari NK, et al. Assessment of global incidence and mortality of hospital-treated sepsis. Current estimates and limitations. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2016;193(3):259–272. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201504-0781OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torio CM, Moore BJ. National Inpatient Hospital Costs: the Most Expensive Conditions by Payer, 2013: Statistical Brief #204. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); Rockville (MD), USA: 2016. pp. 1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vincent JL, Rello J, Marshall J, et al. International study of the prevalence and outcomes of infection in intensive care units. JAMA. 2009;302(21):2323–2329. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ward NS, Levy MM. Sepsis Definitions, Pathophysiology and the Challenge of Bedside Management. Springer International Publishing AG Gewerbestrasse 11 CH-6330 Cham (ZG); Switzerland: 2017. pp. 7–70.www.springer.com/gp/about-springer/company-information/locations/springer-international-publishing-ag [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fink MP, Warren HS. Strategies to improve drug development for sepsis. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014;13:741–758. doi: 10.1038/nrd4368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Netea MG, Balkwill F, Chonchol M, et al. A guiding map for inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 2017;18:826–831. doi: 10.1038/ni.3790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van der Poll T, Van de Veerdonk FL, Scicluna BP, Netea MG. The immunopathology of sepsis and potential therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017;17(7):407–420. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Reviews sepsis pathogenesis and treatments.

- 11.Angus DC, Van der Poll T. Severe sepsis and septic shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369(9):840–851. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hotchkiss RS, Tinsley KW, Swanson PE, et al. Sepsis-induced apoptosis causes progressive profound depletion of B and CD4+ T lymphocytes in humans. J. Immunol. 2001;166(11):6952–6963. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boomer JS, To K, Chang KC, et al. Immunosuppression in patients who die of sepsis and multiple organ failure. JAMA. 2011;306(23):2594–2605. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Otto GP, Sossdorf M, Claus RA, et al. The late phase of sepsis is characterized by an increased microbiological burden and death rate. Crit. Care. 2011;15(4):R183. doi: 10.1186/cc10332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbas AK, Lichtman AH, Pillai S. Cellular and Molecular Immunology (6th Edition) Saunders Elsevier; Philadelphia, USA: 2007. p. 572. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balk RA. Optimum treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock: evidence in support of the recommendations. Dis. Mon. 2004;50(4):168–213. doi: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US National Library of Medicine, Clinical Trials Gov 2018. https://clinicaltrials.gov

- 18.Bernard GR, Vincent J-L, Laterre P-F, et al. Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;344(10):699–709. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103083441001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abraham E, Laterre PF, Garg R, et al. Drotrecogin alfa (activated) for adults with severe sepsis and a low risk of death. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353(13):1332–1341. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ranieri VM, Thompson BT, Barie PS, et al. Drotrecogin alfa (activated) in adults with septic shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366(22):2055–2064. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conway EM, Van De Wouwer M, Pollefeyt S, et al. The lectin-like domain of thrombomodulin confers protection from neutrophil-mediated tissue damage by suppressing adhesion molecule expression via nuclear factor κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. J. Exp. Med. 2002;196(5):565–577. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.US National Library of Medicine. Phase III safety and efficacy study of ART-123 in subjects with severe sepsis and coagulopathy. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT01598831

- 23.Saito H, Maruyama I, Shimazaki S, et al. Efficacy and safety of recombinant human soluble thrombomodulin (ART-123) in disseminated intravascular coagulation: results of a Phase III, randomized, double-blind clinical trial. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2007;5(1):31–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green RH, Brightling CE, Mckenna S, et al. Asthma exacerbations and sputum eosinophil counts: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9347):1715–1721. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11679-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gibbison B, López-López JA, Higgins JPT, et al. Corticosteroids in septic shock: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Crit. Care. 2017;21(1):78. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1659-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patil NK, Bohannon JK, Sherwood ER. Immunotherapy: a promising approach to reverse sepsis-induced immunosuppression. Pharmacol. Res. 2016;111:688–702. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Unsinger J, Mcglynn M, Kasten KR, et al. IL-7 promotes T cell viability, trafficking, and functionality and improves survival in sepsis. J. Immunol. 2010;184(7):3768–3779. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shindo Y, Fuchs AG, Davis CG, et al. Interleukin 7 immunotherapy improves host immunity and survival in a two-hit model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2017;101(2):543–554. doi: 10.1189/jlb.4A1215-581R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hazarika M, Chuk MK, Theoret MR, et al. U.S. FDA Approval Summary: nivolumab for treatment of unresectable or metastatic melanoma following progression on Ipilimumab. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017;23(14):3484–3488. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weinstock C, Khozin S, Suzman D, et al. U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval summary: atezolizumab for metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017;23(16):4534–4539. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang KC, Burnham CA, Compton SM, et al. Blockade of the negative co-stimulatory molecules PD-1 and CTLA-4 improves survival in primary and secondary fungal sepsis. Crit. Care. 2013;17(3):R85. doi: 10.1186/cc12711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ting HH, Timimi FK, Boles KS, Creager SJ, Ganz P, Creager MA. Vitamin C improves endothelium-dependent vasodilation in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;97(1):22–28. doi: 10.1172/JCI118394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marik PE, Khangoora V, Rivera R, Hooper MH, Catravas J. Hydrocortisone, vitamin C, and thiamine for the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock: a retrospective before-after study. Chest. 2017;151(6):1229–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zabet MH, Mohammadi M, Ramezani M, Khalili H. Effect of high-dose ascorbic acid on vasopressor's requirement in septic shock. J. Res. Pharm. Pract. 2016;5(2):94–100. doi: 10.4103/2279-042X.179569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.US National Library of Medicine. Vitamin C and septic shock. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03338569

- 36.Ziegler EJ, Mccutchan JA, Fierer J, et al. Treatment of gram-negative bacteremia and shock with human antiserum to a mutant Escherichia coli. N. Engl. J. Med. 1982;307(20):1225–1230. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198211113072001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shao B, Munford RS, Kitchens R, Varley AW. Hepatic uptake and deacylation of the LPS in bloodborne LPS-lipoprotein complexes. Innate Immun. 2012;18(6):825–833. doi: 10.1177/1753425912442431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rustici A, Velucchi M, Faggioni R, et al. Molecular mapping and detoxification of the lipid A binding site by synthetic peptides. Science. 1993;259(5093):361–365. doi: 10.1126/science.8420003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turner J, Cho Y, Dinh NN, Waring AJ, Lehrer RI. Activities of LL-37, a cathelin-associated antimicrobial peptide of human neutrophils. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998;42(9):2206–2214. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.9.2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.David SA, Bechtel B, Annaiah C, Mathan VI, Balaram P. Interaction of cationic amphiphilic drugs with lipid A: implications for development of endotoxin antagonists. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Lipids Lipid Metab. 1994;1212(2):167–175. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(94)90250-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.David SA, Silverstein R, Amura CR, Kielian T, Morrison DC. Lipopolyamines: novel antiendotoxin compounds that reduce mortality in experimental sepsis caused by gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999;43(4):912–919. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.4.912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burns MR, Wood SJ, Miller KA, Nguyen T, Cromer JR, David SA. Lysine-spermine conjugates: hydrophobic polyamine amides as potent lipopolysaccharide sequestrants. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005;13(7):2523–2536. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anspach FB. Endotoxin removal by affinity sorbents. J. Biochem. Bioph. Methods. 2001;49(1–3):665–681. doi: 10.1016/s0165-022x(01)00228-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thomas CJ, Gangadhar BP, Surolia N, Surolia A. Kinetics and mechanism of the recognition of endotoxin by polymyxin B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120(48):12428–12434. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vattimo MDFF, Watanabe M, Da Fonseca CD, Neiva LBDM, Pessoa EA, Borges FT. Polymyxin B nephrotoxicity: from organ to cell damage. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(8):e0161057. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsigos I, Bouriotis V. Purification and characterization of chitin deacetylase from Colletotrichum lindemuthianum. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270(44):26286–26291. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.44.26286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gades MD, Stern JS. Chitosan supplementation and fecal fat excretion in men. Obes. Res. 2003;11(5):683–688. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fei Liu X, Lin Guan Y, Zhi Yang D, Li Z, Yao F. Antibacterial action of chitosan and carboxymethylated chitosan. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2001;79:1324–1335. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sogias IA, Khutoryanskiy VV, Williams AC. Exploring the factors affecting the solubility of chitosan in water. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2010;211(4):426–433. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu P, Bajaj G, Shugg T, Van Alstine WG, Yeo Y. Zwitterionic chitosan derivatives for pH-sensitive stealth coating. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11(9):2352–2358. doi: 10.1021/bm100481r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bajaj G, Van Alstine WG, Yeo Y. Zwitterionic chitosan derivative, a new biocompatible pharmaceutical excipient, prevents endotoxin-mediated cytokine release. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(1):e30899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu KC, Yeo Y. Zwitterionic chitosan–polyamidoamine dendrimer complex nanoparticles as a pH-sensitive drug carrier. Mol. Pharm. 2013;10(5):1695–1704. doi: 10.1021/mp300522p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Park J, Pei Y, Hyun H, Castanares MA, Collins DS, Yeo Y. Small molecule delivery to solid tumors with chitosan-coated PLGA particles: a lesson learned from comparative imaging. J. Control. Rel. 2017;268:407–415. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cho EJ, Doh KO, Park J, et al. Zwitterionic chitosan for the systemic treatment of sepsis. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:29739. doi: 10.1038/srep29739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hyun H, Hashimoto-Hill S, Kim M, Tsifansky MD, Kim CH, Yeo Y. Succinylated chitosan derivative has local protective effects on intestinal inflammation. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2017;3(8):1853–1860. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.7b00262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chae SY, Jin C-H, Shin JH, et al. Biochemical, pharmaceutical and therapeutic properties of long-acting lithocholic acid derivatized exendin-4 analogs. J. Control. Rel. 2010;142(2):206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ashton S, Song YH, Nolan J, et al. Aurora kinase inhibitor nanoparticles target tumors with favorable therapeutic index in vivo. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016;8(325):1–10. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad2355. 325ra317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gabizon A, Catane R, Uziely B, et al. Prolonged circulation time and enhanced accumulation in malignant exudates of doxorubicin encapsulated in polyethylene-glycol coated liposomes. Cancer Res. 1994;54(4):987–992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Green MR, Manikhas GM, Orlov S, et al. Abraxane®, a novel Cremophor®-free, albumin-bound particle form of paclitaxel for the treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2006;17(8):1263–1268. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lam SJ, O'brien-Simpson NM, Pantarat N, et al. Combating multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria with structurally nanoengineered antimicrobial peptide polymers. Nat. Microbiol. 2016;1(11):16162. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Soh M, Kang DW, Jeong HG, et al. Ceria-Zirconia nanoparticles as an enhanced multi-antioxidant for sepsis treatment. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2017;56(38):11399–11403. doi: 10.1002/anie.201704904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang Z, Li J, Cho J, Malik AB. Prevention of vascular inflammation by nanoparticle targeting of adherent neutrophils. Nat. Nanotech. 2014;9:204–210. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Describes nanoparticles (NPs) targeting activated neutrophils for treatment of vascular inflammation.

- 63.Spence S, Greene MK, Fay F, et al. Targeting Siglecs with a sialic acid-decorated nanoparticle abrogates inflammation. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015;7(303):303ra140. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab3459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Describes NPs targeting macrophages via sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectins for treatment of acute inflammation.

- 64.Miksa M, Wu R, Dong W, et al. Immature dendritic cell-derived exosomes rescue septic animals via milk fat globule epidermal growth factor VIII. J. Immunol. 2009;183(9):5983–5990. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang X, Gu H, Qin D, et al. Exosomal miR-223 contributes to mesenchymal stem cell-elicited cardioprotection in polymicrobial sepsis. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:13721. doi: 10.1038/srep13721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hu CMJ, Fang RH, Copp J, Luk BT, Zhang LF. A biomimetic nanosponge that absorbs pore-forming toxins. Nat. Nanotech. 2013;8(5):336–340. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Thamphiwatana S, Angsantikul P, Escajadillo T, et al. Macrophage-like nanoparticles concurrently absorbing endotoxins and proinflammatory cytokines for sepsis management. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114(43):11488–11493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1714267114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Henry BD, Neill DR, Becker KA, et al. Engineered liposomes sequester bacterial exotoxins and protect from severe invasive infections in mice. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014;33:81. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Describes artificial liposomes neutralizing bacterial exotoxins.

- 69.Kang JH, Super M, Yung CW, et al. An extracorporeal blood-cleansing device for sepsis therapy. Nat. Med. 2014;20(10):1211–1216. doi: 10.1038/nm.3640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Describes the application of magnetic NPs in extracorporeal blood-cleansing device.

- 70.Sondi I, Salopek-Sondi B. Silver nanoparticles as antimicrobial agent: a case study on E. coli as a model for Gram-negative bacteria. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2004;275(1):177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2004.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Le Ouay B, Stellacci F. Antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles: a surface science insight. Nano Today. 2015;10(3):339–354. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pal S, Tak YK, Song JM. Does the antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles depend on the shape of the nanoparticle? A study of the Gram-negative bacterium Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73(6):1712–1720. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02218-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lansdown AB. Silver in health care: antimicrobial effects and safety in use. Curr. Probl. Dermatol. 2006;33:17–34. doi: 10.1159/000093928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Korsvik C, Patil S, Seal S, Self WT. Superoxide dismutase mimetic properties exhibited by vacancy engineered ceria nanoparticles. Chem. Commum. (Camb.) 2007;(10):1056–1058. doi: 10.1039/b615134e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pirmohamed T, Dowding JM, Singh S, et al. Nanoceria exhibit redox state-dependent catalase mimetic activity. Chem. Commum. (Camb.) 2010;46(16):2736–2738. doi: 10.1039/b922024k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Howes PD, Chandrawati R, Stevens MM. Colloidal nanoparticles as advanced biological sensors. Science. 2014;346(6205):1247390. doi: 10.1126/science.1247390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Haes AJ, Haynes CL, Mcfarland AD, Schatz GC, Van Duyne RR, Zou SL. Plasmonic materials for surface-enhanced sensing and spectroscopy. MRS Bull. 2005;30(5):368–375. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chegel V, Rachkov O, Lopatynskyi A, et al. Gold nanoparticles aggregation: drastic effect of cooperative functionalities in a single molecular conjugate. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2012;116(4):2683–2690. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chapman R, Lin Y, Burnapp M, et al. Multivalent nanoparticle networks enable point-of-care detection of human phospholipase-A2 in serum. ACS Nano. 2015;9(3):2565–2573. doi: 10.1021/nn5057595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schrama AJ, De Beaufort AJ, Poorthuis BJ, Berger HM, Walther FJ. Secretory phospholipase A(2) in newborn infants with sepsis. J. Perinatol. 2008;28(4):291–296. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Evans R, Lellouch AC, Svensson L, Mcdowall A, Hogg N. The integrin LFA-1 signals through ZAP-70 to regulate expression of high-affinity LFA-1 on T lymphocytes. Blood. 2011;117(12):3331–3342. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-289140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ando M, Tu W, Nishijima K, Iijima S. Siglec-9 enhances IL-10 production in macrophages via tyrosine-based motifs. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;369(3):878–883. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.02.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Terrasini N, Lionetti V. Exosomes in critical illness. Crit. Care Med. 2017;45(6):1054–1060. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wu J, Wang Y, Li L. Functional significance of exosomes applied in sepsis: a novel approach to therapy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Basis Dis. 2017;1863(1):292–297. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mcdonald MK, Tian Y, Qureshi RA, et al. Functional significance of macrophage-derived exosomes in inflammation and pain. Pain. 2014;155(8):1527–1539. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Janiszewski M, Do Carmo AO, Pedro MA, Silva E, Knobel E, Laurindo FR. Platelet-derived exosomes of septic individuals possess proapoptotic NAD(P)H oxidase activity: a novel vascular redox pathway. Crit. Care Med. 2004;32(3):818–825. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000114829.17746.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Teng H, Hu M, Yuan LX, et al. Suppression of inflammation by tumor-derived exosomes: a kind of natural liposome packaged with multifunctional proteins. J. Liposome Res. 2012;22(4):346–352. doi: 10.3109/08982104.2012.710911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang J-F, Yu M-L, Yu G, et al. Serum miR-146a and miR-223 as potential new biomarkers for sepsis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010;394(1):184–188. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhou J, Chaudhry H, Zhong Y, et al. Dysregulation in microRNA expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of sepsis patients is associated with immunopathology. Cytokine. 2015;71(1):89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wu S-C, Yang JC-S, Rau C-S, et al. Profiling circulating microRNA expression in experimental sepsis using cecal ligation and puncture. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e77936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Alexander M, Hu R, Runtsch MC, et al. Exosome-delivered microRNAs modulate the inflammatory response to endotoxin. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7321. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hu C-MJ, Zhang L, Aryal S, Cheung C, Fang RH, Zhang L. Erythrocyte membrane-camouflaged polymeric nanoparticles as a biomimetic delivery platform. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108(27):10980–10985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106634108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fang RH, Luk BT, Hu CM, Zhang L. Engineered nanoparticles mimicking cell membranes for toxin neutralization. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2015;90:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Highlights different types of cell-membrane mimicking NPs as a potential antagonist for toxin neutralization.

- 94.Hu CM, Fang RH, Wang KC, et al. Nanoparticle biointerfacing by platelet membrane cloaking. Nature. 2015;526(7571):118–121. doi: 10.1038/nature15373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cruz DN, Antonelli M, Fumagalli R, et al. Early use of polymyxin B hemoperfusion in abdominal septic shock: the EUPHAS randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301(23):2445–2452. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Payen DM, Guilhot J, Launey Y, et al. Early use of polymyxin B hemoperfusion in patients with septic shock due to peritonitis: a multicenter randomized control trial. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(6):975–984. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-3751-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Herrmann IK, Urner M, Graf S, et al. Endotoxin removal by magnetic separation-based blood purification. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2013;2(6):829–835. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201200358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lee J-J, Jeong KJ, Hashimoto M, et al. Synthetic ligand-coated magnetic nanoparticles for microfluidic bacterial separation from blood. Nano Lett. 2014;14(1):1–5. doi: 10.1021/nl3047305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wang J, Wu H, Yang Y, et al. Bacterial species-identifiable magnetic nanosystems for early sepsis diagnosis and extracorporeal photodynamic blood disinfection. Nanoscale. 2018;10(1):132–141. doi: 10.1039/c7nr06373c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.