Abstract

Background:

Snakebites lead to at least 421,000 envenomations and result in more than 20,000 deaths per year worldwide. Few reports exist in the Mediterranean region. This study describes demographic and clinical characteristics, treatment modalities, and outcomes of snakebites in Lebanon.

Materials and Methods:

This was a retrospective chart review of patients who presented with snakebite complaint to the emergency department between January 2000 and September 2014.

Results:

A total of 24 patients were included in this study. The mean age was 34.6 (±16.4) years and 58.3% were males. Local manifestations were documented in 15 (62.5%) patients, systemic effects in 10 (41.7%), hematologic abnormalities in 10 (41.7%), and neurologic effects in 4 (16.7%) patients. Nine patients (37.5%) received antivenom. The median amount of antivenom administered was 40 ml or 4 vials (range: 1–8 vials). About 50% of patients were admitted to the hospital with 75% to an Intensive Care Unit and 25% to a regular bed. All were discharged home with a median hospital length of stay of 4 (interquartile range 11) days. Among those admitted, seven patients (58.3%) had at least one documented complication (compartment syndrome, fasciotomy, intubation, deep vein thrombosis, coagulopathy, acute respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis, congestive heart failure, cellulitis, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and vaginal bleeding).

Conclusion:

Victims of snakebites in Lebanon developed local, systemic, hematologic, or neurologic manifestations. Complications from snakebites were frequent despite antivenom administration. Larger studies are needed to assess the efficacy of available antivenom and to possibly create a local antivenom for the treatment of snakebites in Lebanon.

Keywords: Antivenin, Daboia palaestinae, Lebanon, Macrovipera lebetina, Montivipera bornmuelleri, snakebites

INTRODUCTION

Snakebites lead to at least 421,000 envenomations and 20,000 deaths worldwide on yearly basis.[1] Assessing the national burden of snakebites in a country is crucial for ensuring proper resource allocation and availability of antivenom. Snakebites in Lebanon have been poorly studied despite their potential public health impact. The literature regarding this topic is scarce with the last article published in 1953.[2] Little is known about affected victims, types of snakes involved, treatment modalities, or clinical practice related to snakebites in Lebanon.

Recently, the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health published treatment and management guidelines for snakebites in Lebanon, but these have not yet been evaluated in terms of their adoption, effectiveness, and outcomes.[3]

The aim of this study is to describe the demographic and clinical characteristics, treatment modalities and outcomes of snakebite victims treated at a tertiary care hospital in Beirut, Lebanon.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study setting and design

The study was conducted in an urban emergency department (ED) at the American University of Beirut Medical Center (AUBMC). AUBMC is the largest tertiary care center in Lebanon, with around 52,000 ED patient visits per year.

A retrospective chart review of patients who presented to the ED between January 1, 2000, and September 30, 2014, with a chief complaint of snakebite was done. The study was approved by the AUB Institutional Review Board.

Data collection

Trained research assistants collected the data from the electronic health records of patients. Event-related information included patients’ demographics and characteristics, geographic location of bite, snake species (if identified), time to bite, time of bite to ED arrival, and mode of transport. Local, systemic, neurologic, and hematologic clinical manifestations were collected. In addition, investigators retrieved from the medical records the following information related to the clinical course: vital signs, ED treatment, medications administered, antivenom dose when administered and whether invasive procedures were performed (intubation, fasciotomy, drainage, and venous catheter insertion), ED disposition, complications, and patient outcome.

Data analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 22 (Statistical Package for Social Sciences, IBM, New York, USA). Descriptive statistics were calculated. The categorical variables were summarized by their frequency distributions whereas the continuous variables were presented as means with standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs).

RESULTS

A total of 24 patients were included in the study. None of the patients were excluded from the study. The mean age was 34.6 (±16.4) years (range: 1–69 years) with 58.3% being males. Most snakebite victims were in the 30–49-year-old age group (54.2%) followed by the 10–29-year-old age group (29.2%).

Most patients presented to ED by private vehicle (93.3%). The majority (66.7%) presented to our ED for initial care, the rest (33.3%) were referred from other hospitals.

The majority of cases were from Beirut and neighboring suburb Baabda (Southern suburb of Beirut). The snake species was confirmed in only one case where the patient brought the snake with him [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Snake caught by one of the patients (Daboia palaestinae)

Most bites were to the lower limbs (60.0%) followed by upper limbs (33.4%) and both upper and lower limbs (6.6%).

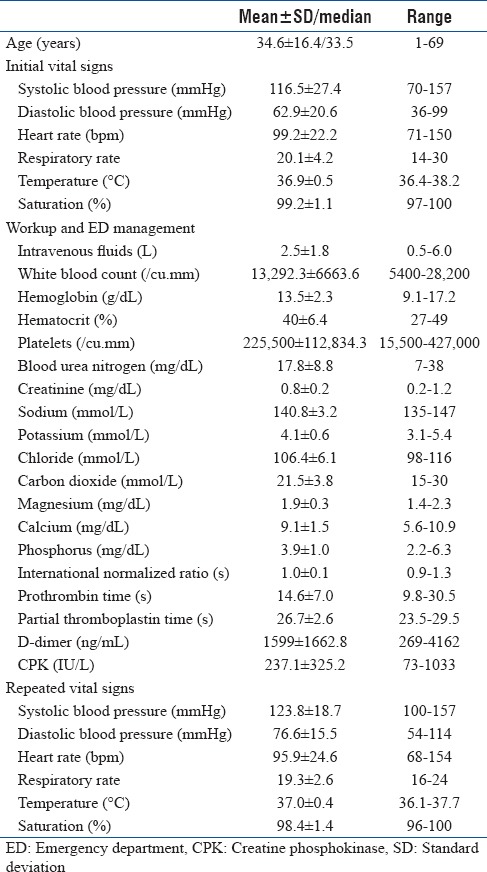

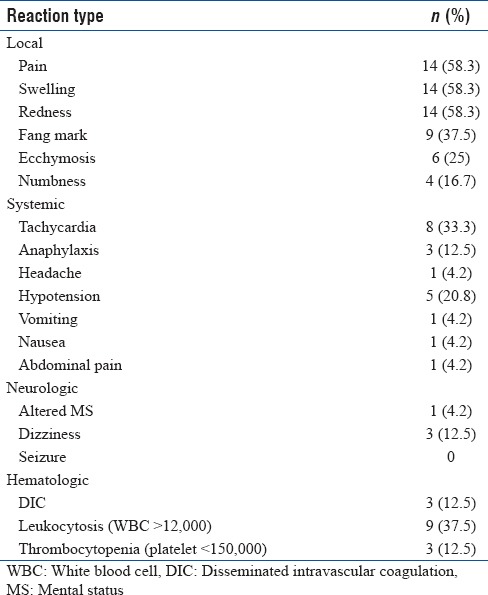

The median time interval from “bite to ED presentation” was 1 h (IQR of 4). The presenting vital signs and ED workup are presented in Table 1. All patients received initial intravenous fluids, antihistamine (diphenhydramine), and steroids (hydrocortisone). Clinical manifestations were classified into local, systemic, hematologic, and neurologic [Table 2]. Local clinical manifestations were seen in the majority of cases (62.5%) and included pain (58.3%), swelling (58.3%) and redness (58.3%), fang marks (37.5%), ecchymosis (25.0%), and numbness (16.7%).

Table 1.

Characteristics, vital signs, and laboratory values of study patients

Table 2.

Documented reaction type in study population

Systemic effects were observed in 10 (41.7%) patients. These included tachycardia (33.3%), hypotension (20.8%) and anaphylaxis (12.5%), headache (4.2%), nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain (4.2% each). Hematologic abnormalities were evident in 10 (41.7%) patients, mainly leukocytosis (37.5%), coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia (12.5% each). Anaphylaxis was due to the antivenom in only one case out of 3 cases with anaphylaxis. Neurologic abnormalities were seen in only 4 (16.7%) patients including dizziness (12.5%) and altered mental status (4.2%).

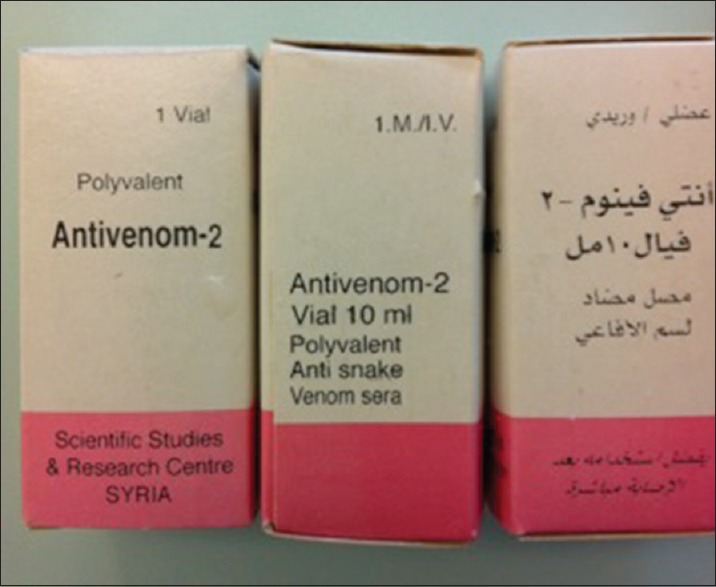

Nine patients (37.5%) received antivenom (Polyvalent Antivenom−2, manufactured by Scientific Studies and Research Center [SSRC] in Syria) [Figure 2]. The median amount of antivenom administered was 40 ml or 4 vials (range: 1–8 vials). The median time interval from “bite to antivenom” was 3.33 h (IQR of 22).

Figure 2.

Antivenom in Lebanon (Syria Scientific Studies and Research Center)

Twelve patients (50%) were admitted to the hospital with 9 (75%) to an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and 3 (25%) to a regular bed. Among those who were admitted to an ICU (67% of them) received antivenom. The median hospital stay was 4 days (IQR of 11). All were eventually discharged home in good condition.

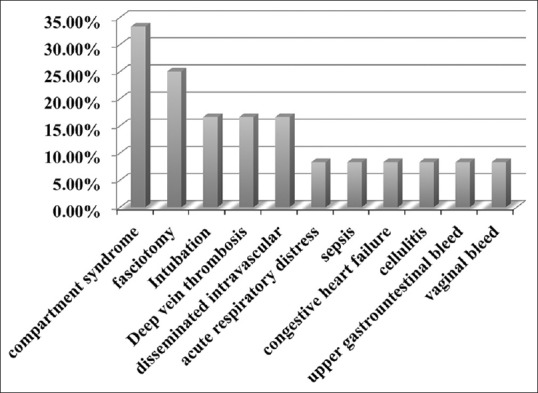

Among those admitted seven patients (58.3%) had at least one documented complication during their inpatient stay [Figure 3]. Compartment syndrome occurred in 4 (33.3%) cases. Compartment syndrome was diagnosed clinically by the orthopedic surgeon and intracompartmental pressures were not measured. Fasciotomy was done in 3 out of the 4 cases that were diagnosed with compartment syndrome. Coagulopathy occurred in 16.6% of admitted patients as a complication of snakebite. None of these patients received antivenom. Other complications included: deep vein thrombosis (16.6%), acute respiratory distress syndrome (8.3%), sepsis (8.3%), congestive heart failure (8.3%), cellulitis (8.3%), upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleed (8.3%), and vaginal bleed (8.3%). Two patients out of those admitted had significant complications. The first patient was a 19-year-old female who developed coagulopathy, upper GI bleed, vaginal bleed, and compartment syndrome after being bit on her left lower extremity (LLE) by an unknown snake species. She presented 72 h after the bite and antivenom was not given for unknown reasons. She survived to hospital discharge after 33 days of admission (2 days in ICU and 31 days in the regular floor) with no sequelae. The second patient was a 46-year-old male who had respiratory failure and required mechanical ventilation after he was bit on his LLE by an unknown snake. His hospital course was complicated by sepsis, congestive heart failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, deep vein thrombosis to his right upper extremity, and compartment syndrome in his LLE. He was transferred to our facility after he was admitted for 10 days at an outside facility where he had received antivenom. He survived to hospital discharge with no sequelae after 46 days of admission (45 days in ICU and 1 day on the regular floor).

Figure 3.

Complications among admitted patients

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to describe characteristics, treatment modalities, and clinical outcomes of snakebite victims in Lebanon. Understanding the current clinical practice related to this disease is important and can guide future prevention efforts and the development of management guidelines.

Lebanon has around 25 species of snakes, three of which are venomous vipers (all vipers): Daboia palaestinae (Werner, 1938) [Figure 4], Macrovipera lebetina (Linnaeus, 1758) [Figure 5], and Montivipera bornmuelleri (known as Lebanon viper) [Figure 6]. There are back-fanged venomous snakes such as Telescopus fallax (Fleischmann, 1831), Malpolon monspessulanus (Hermann 1804), and Micrelaps muelleri (Boettger 1880) but there are no data about incidents of envenomation by these snakes. Other nonvenomous snakes in Lebanon are mostly colubrids (Hraoui-Bloquet 2002).[4]

Figure 4.

Daboia palaestinae. Photo courtesy of Professor Riad Sadek (American University of Beirut Medical Center)

Figure 5.

Macrovipera lebetina. Photo courtesy of Professor Riad Sadek (American University of Beirut Medical Center)

Figure 6.

Montivipera bornmuelleri. Photo courtesy of Professor Riad Sadek (American University of Beirut Medical Center)

M. bornmuelleri has different characteristics than the two other vipers species recorded in Lebanon (M. lebetina and D. palaestinae).[5] Its size barely exceeds 60 cm compared to the size of M. lebetina and D. palaestinae, which can reach up to 1.50 m. M. bornmuelleri is also found only at very high altitudes (>1800 m) with very restricted overlap with human habitation, while the other two viper species live in forests and rocky areas within an altitude range that extends from the coast up to 1600 m[5] with considerable overlap with human habitation especially in rural areas.

Viperidae venoms consist of different proteins, nucleotides, and inorganic ions. These are responsible for the venom toxicity, which affects the coagulation cascade and leads to bleeding.[5]

In this study, hematologic abnormalities were evident in 41.7% of our patients, and these mainly included leukocytosis, coagulopathy, and thrombocytopenia. The snake species was identified in only one patient (D. palaestinae), however, patients were mostly bitten in the geographic location where M. lebetina and D. palaestinae are commonly present.

Understanding the venom properties of venomous snakes in Lebanon is crucial to anticipate reactions in snakebite victims and thus alert people and have antivenoms available in the hospitals around the natural habitats of those snakes.

A study by Kakanj et al. examined the direct toxicity effect of Vipera lebetina crude venom on human umbilical vein endothelial cells and showed that it has significant vascular toxicity putting patients at a risk of edema, internal bleeding, and necrosis due to endothelial cell disruption.[6]

M. bornmuelleri was placed on the international union for conservation of nature (IUCN) red list of endangered species in 2006 because of its fragmented geographic distribution. Very few studies regarding the biology of this endemic and rare species exist. M. bornmuelleri venom is a complex mixture of proteins, with dual effect on human blood coagulation having either pro- or anti-coagulant activity at different concentrations.[5,7]

Vipera palaestinae venom contains multiple hydrolytic enzymes responsible for cell membrane and endothelial damage and can lead to hematologic abnormalities in bite victims.[8,9,10,11] One study showed that 19% of children bitten by V. palaestinae species develop severe sequelae and require ICU admission.[12] The early administration of antivenom for these patients has also shown to be beneficial.[13]

Snakebite victims seeking emergency care were not frequent in our urban setting. Only two cases per year were treated in our ED during the study. They presented from central Beirut and Western areas of Lebanon. The patients were mainly young adults (mean age was 34.6 ± 16.4 years) with males being affected more often than females.

Clinical manifestations of snakebites were common. The majority of patients were symptomatic with two-thirds having local signs (half of the patients had systemic and hematologic manifestations, and a minority developed neurologic abnormalities). Compartment syndrome occurred in a larger than expected number of admitted patients (33.3%). None of those patients received antivenom, which begs the question of whether this complication could have been prevented with early and appropriate antivenom administration.

All our patients received systemic steroids as part of snakebite treatment although current practice guidelines do not support their use.[14] Coagulopathy occurred in 16.6% of admitted patients and was transient despite the fact that none of these patients received antivenom. Whether antivenom administration would have reversed this complication or not was not assessed by our study.

Interestingly, there was a high admission rate among snakebite victims in this study (75% to ICU and 25% to the regular floor) with complications affecting 58% of admitted patients, which exceeds rates reported by other studies of Vipera palaestinea snakebites.[15,16] The rate of fasciotomies in patients was also high (25%) compared to other studies (0% reported by Ince and Gundeslioglu and 4% by Lawrence et al.[17,18] Fasciotomy was done in 3 out of 4 patients who were diagnosed clinically with compartment syndrome. The decision to do a fasciotomy was based on clinical examination done by an orthopedic surgeon, and compartment pressures were not measured.

Antivenoms are either monovalent or polyvalent, depending on the number of species whose venoms are used for immunization.[19] Despite the high efficacy of the monovalent antivenom, polyvalent antivenom production is often preferred in many countries as snake species identification is generally not possible by the treating physician.[19] Choice of antivenom in Lebanon is limited to available stockpiles of imported antivenoms, as no antivenoms are currently produced in this country, but are, rather, imported from Syria or Saudi Arabia. The Syrian antivenom, (Antivenom−2, Polyvalent Anti Snake Venom) is manufactured by SSRC in Syria. It is prepared from pure plasma separated from the blood of healthy horses that are immunized by the most dangerous snake venoms that are widely spread in Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon. Antivenom−2 neutralizes and inactivates the following venoms V. palaestinae, V. lebetina, Vipera ammonites, Cerastes cerastes, Echis carinatus, and Naja naja. Antivernom−2 is thought to cover local snake venoms in Lebanon. Children and adults receive same doses regardless of weight and age. In mild and moderate envenomation, 5–10 ml of antivenom−2 is used intramuscularly. In severe envenomation or delayed treatment, 40 ml of antivenom−2 is used by intravenous infusion after dilution with physiologic serum 1/10 and is administered over 30–60 min. The vial volume is 10 ml. Protein content is 3.5%, and preservative is m-cresol 0.15%. The antivenom should be stored at 2°C–8°C and has a shelf life of 18 months. It is not recommended to be used after the expiration date or if any turbidity or precipitation appears in the antiserum. On the other hand, the Saudi Arabia antivenom is a polyvalent equine-derived antivenom (Registered by the Ministry of Health in Saudi Arabia, registration no. 98/308/2). The NAVPC (National Antivenom and Vaccine Production Center) is a highly purified polyvalent snake antivenom that contains F (ab)2 fractions of the immunoglobulin raised against the venoms of six Saudi land snakes. Its produced in the Saudi Arabia Kingdom and distributed only by the Al Haya medical company in the kingdom and its neighboring countries.[20] Gradual increasing doses of local snake's venoms from (Bitis arietans, Echis coloratus, E. carinatus, Naja haje, C. cerastes, Walterinesia aegyptia) in addition to immunomodulators are used to hyperimmunize healthy Arabian horses to prepare the antivenom. The polyvalent antivenom has a broad-spectrum activity and can neutralize the toxic effects of the six Saudi snake venoms, as well as, the venom of many of the Middle Eastern and North African snakes including (Bitis caudalis, Bitis gabonica, Naja melanolleuca, N. naja, and Naja nigricollis). This antivenom neutralizes hemorrhagic, myonecrotic, and neuromuscular blocking effects as well as the cardiotoxic effects of many viper and elapid snake venoms. It is available in 10 ml ampoules and is stored in the dark (4°C ± 2°C) with a 3-year shelf life.[20]

The observed high rate of complications among admitted patients is possibly related to delay in seeking medical care at the hospital and delay in administration of the antivenom. Choice of antivenom in Lebanon is limited to available stockpiles of imported antivenoms. During the study, antivenom was being imported from Syria. According to the manufacturer, this antivenom is effective against two Lebanese venomous snakes (V. lebetina and V. palaestinae) with unclear indications against the Lebanon viper (M. bornmuelleri). The efficacy of this antivenom has not been previously examined in managing specific venomous snakebites in Lebanon. Our results, however, show that patients who received antivenom had a large variation in their hospital stays (median 4 days, IQR 11 days) and serious complications requiring intensive care admissions (67%). This finding questions the efficacy of the imported antivenoms against our own venomous snakes. The imported Saudi Arabia antivenom which was not used in our study is also according to the manufacturer not effective against venomous snake species that exist in Lebanon. Despite this, there were instances where the Ministry of Health imported the Saudi Arabia antivenom. In addition to the limited efficacy of these antivenoms, access to antivenoms, in general, is problematic in Lebanon with limited stock available in only specific sites. Dispensing antivenom to other peripheral hospitals is also restricted and requires the approval of the Ministry of Public Health. Antivenoms are not available in every hospital, and often patients need to be transferred to facilities where the antivenom is available. This access limitation affects patient care and timely administration of antivenom. Both the limited efficacy of and access to antivenoms in Lebanon should prompt the Ministry of Health to address this issue by highlighting the importance of this topic and to work on potentially manufacturing local antivenom for increased access and availability in hospitals across Lebanon.

Limitations

The results of our study should be considered in the setting of its limitations. The sample size is small however the study highlights important clinical characteristics and outcomes of victims of snakebites, which have not been previously reported in Lebanon. The study also includes data from only one medical center in Beirut, an urban setting that might not be reflective of other more rural settings. In addition, the documentation of some complications might have been missing from the medical records, a limitation that is inherent to retrospective medical records-based studies.

CONCLUSION

Victims of snakebites in Lebanon developed local, systemic, hematologic, or neurologic manifestations. Complications from the snakebite were frequent. Larger studies are needed to establish better guidelines for the treatment of snakebites in Lebanon and to assess the efficacy of currently used antivenom in addition to possibly creating a local antivenom.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil,

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kasturiratne A, Wickremasinghe AR, de Silva N, Gunawardena NK, Pathmeswaran A, Premaratna R, et al. The global burden of snakebite: A literature analysis and modelling based on regional estimates of envenoming and deaths. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e218. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Attar S, Nassif RE. Snake bite and snakes in Lebanon. J Med Liban. 1953;6:366–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lebanese Ministry of Public Health Guidelines for Snakebites. [Last accessed on 2016 Dec 08]. Available from: http://www.moph.gov.lb/prevention/surveillance/documents/toxico_2010_7.pdf .

- 4.Hraoui-Bloquet S, Sadek R, Sindaco R, Venchi A. The herpetofauna of lebanon: New data on distribution. Zool Middle East. 2002;27:35–46. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hraoui-Bloquet S, Sadek R, Accary C, Hleihel W, Fajloun Z. An ecological study of the lebanon mountain viper Montivipera bornmuelleri (Werner, 1898) with a preliminary biochemical characterization of its venom. Leban Sci J. 2012;13:89–101. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kakanj M, Ghazi-Khansari M, Zare Mirakabadi A, Daraei B, Vatanpour H. Cytotoxic effect of Iranian Vipera lebetina snake venom on HUVEC cells. Iran J Pharm Res. 2015;14:109–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Accary C, Rima M, Kouzayha A, Hleihel W, Sadek W, Defontis JC. Effect of the Montivipera bornmuelleri snake venom on human blood: Coagulation disorders and hemolytic activities. Open J Hematol. 2014;5:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKay DG, Moroz C, De Vries A, Csavossy I, Cruse V. The action of hemorrhagin and phospholipase derived from Vipera palestinae venom on the microcirculation. Lab Invest. 1970;22:387–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Vries A, Grotto L, Moroz C, Goldblum N. Studies on the hemorrhagin of Vipera palestinae venom. Ind Med Surg. 1967;36:205–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winkler E, Chovers M, Almog S, Pri-Chen S, Rotenberg M, Tirosh M, et al. Decreased serum cholesterol level after snake bite (Vipera palaestinae) as a marker of severity of envenomation. J Lab Clin Med. 1993;121:774–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grotto L, Jerushalmy Z, De Vries A. Effect of purified Vipera palestinae hemorrhagin on blood coagulation and platelet function. Thromb Diath Haemorrh. 1969;22:482–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paret G, Ben-Abraham R, Ezra D, Shrem D, Eshel G, Vardi A, et al. Vipera palaestinae snake envenomations: Experience in children. Hum Exp Toxicol. 1997;16:683–7. doi: 10.1177/096032719701601110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bentur Y, Zveibel F, Adler M, Raikhlin B. Delayed administration of Vipera xanthina palaestinae antivenin. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1997;35:257–61. doi: 10.3109/15563659709001209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nuchprayoon I, Pongpan C, Sripaiboonkij N. The role of prednisolone in reducing limb oedema in children bitten by green pit vipers: A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2008;102:643–9. doi: 10.1179/136485908X311786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shemesh IY, Kristal C, Langerman L, Bourvin A. Preliminary evaluation of Vipera palaestinae snake bite treatment in accordance to the severity of the clinical syndrome. Toxicon. 1998;36:867–73. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(97)00173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bentur Y, Cahana A. Unusual local complications of Vipera palaestinae bite. Toxicon. 2003;41:633–5. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(02)00367-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ince B, Gundeslioglu AO. The management of viper bites on the hand. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2014;39:642–6. doi: 10.1177/1753193413496943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawrence WT, Giannopoulos A, Hansen A. Pit viper bites: Rational management in locales in which copperheads and cottonmouths predominate. Ann Plast Surg. 1996;36:276–85. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199603000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alirol E, Sharma SK, Bawaskar HS, Kuch U, Chappuis F. Snake bite in South Asia: A review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e603. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Polyvalent Snake Antivenom. National Antivenom and Vaccine Production Center. 2015. [Last accessed on 2016 Dec 08]. Available from: http://www.antivenom-center. com/navpc-products/bivalent-snake-antivenom/