Abstract

Background:

Early recognition of Stroke is one of the key concepts in the “Chain of Survival” as described by the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke guidelines. The most commonly used tools for prehospital assessment of stroke are “The Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale,” (CPSS) the “Face, Arm, Speech Test,” and “The Los Angeles Prehospital Stroke Screen.” The former two are used to identify stroke using physical findings while the latter is used to rule out other causes of altered consciousness.

Aim:

The aim of this study is to validate the CPSS in the prehospital setting by correlating with computed tomography scan findings. (1) To determine if these scores can be implemented in the Indian prehospital setting. (2) To determine if it is feasible for new emergency departments (EDs) to use these protocols for early detection of stroke.

Methodology:

A prospective, observational study from December, 2015 to March, 2016. Patients with suspected stroke were enrolled. Data were collected prehospital in patients that arrived to the ED in an ambulance. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of the score were calculated using standard formulae.

Results:

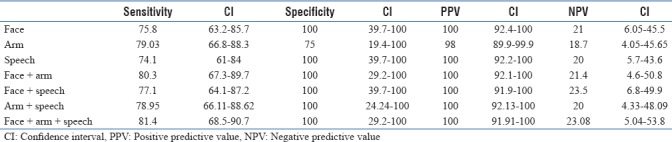

CPSS showed good sensitivity of 81% (confidence interval [CI] – 68.5%–97%) when combined and a positive predictive value (PPV) of 100% (CI: 91.9%–100%). Individually, they showed a sensitivity of 75.8%, 79%, and 74.1%, respectively, with a PPV of 100% and specificity of 95%–100%.

Conclusion:

As a prehospital screening tool, CPSS can be extremely useful as any diagnosis is only provisional until confirmed by an appropriate investigation in a hospital.

Keywords: Cincinnati prehospital stroke scale, face arm speech time, prehospital stroke, stroke South India

INTRODUCTION

Early recognition of stroke is one of the key concepts in the “Chain of Survival” as described by the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke guidelines.[1] The most commonly used tools for the prehospital assessment of stroke are “The Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale” (CPSS), “Face, Arm, Speech Time test” (FAST) and “The Los Angeles Prehospital Stroke Screen” (LAPSS). The former two are used to identify stroke using physical findings while the latter is used to rule out other causes of altered consciousness.

The LAPSS identifies potential stroke victims in the prehospital setting using variables such as the patient's age, past medical history of seizures, current blood sugar, duration of symptoms, current hospitalization status, and motor asymmetry. A study performed in the early 2000's showed it to have a very high positive predictive value (PPV) of about 97% and negative predictive value of 98%.[2] This scoring system was then validated at an urban EMS in China in 2013 and the mean time of completing the LAPSS was found to be 4.3 ± 3 min and the median was found to be 5 min.[3]

In the prehospital setup, a rapid diagnosis is essential to facilitate the early intervention, some even in the ambulance. It is in this aspect that the CPSS and the FAST are preferred over the third. CPSS identifies stroke victims by looking for facial droop, arm drift, and slurring of speech. It takes less than a minute to assess and is fairly accurate with a high specificity for identifying a stroke patient.

Prehospital care is still an emerging field in India. Can these scoring systems be implemented in the Indian prehospital settings? Is it feasible for new emergency departments (EDs) to use these protocols for early detection of stroke?

The primary goal of this study is to identify a rapid and effective means to improve the identification and diagnosis of stroke, thereby improving outcomes.[4] The secondary objectives are to determine if these scores can be implemented in the Indian prehospital setting and to determine if it is feasible for new EDs to use these protocols for early detection of stroke.

METHODOLOGY

Study design

This was a prospective, observational study where the CPSS was validated for its sensitivity, specificity, positive, and negative predictive values both, combined and individually. Patients with suspected stroke were enrolled. Data were collected prehospital in patients that arrived to the ED in an ambulance and in hospital for patients that arrived with other means of transport.

Study setting and population

Our hospital, a regional stroke center, is a multispecialty, tertiary care, teaching hospital with about 3000–4000 ED visits a month. We receive about 20 critically ill patients a day and have three full-fledged Intensive Care Units for medical, neurology, and cardiology. The patients included were those with suspected stroke for whom the CPSS score was calculated.

The study duration was for 4 months from December 2015 to March 2016.

Study protocol

All patients with suspected stroke were enrolled. Patients with documented hypoglycemia or a history of seizures were excluded from the study. Patients who were transferred from other facilities following a diagnosis of stroke were also excluded from the study. The CPSS was calculated but was not considered while clinically assessing the patient and standard protocols such as the “ROSIER” Scale were used depending on physician comfort. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain was then performed for patients with suspected stroke, and the presence of signs of ischemia or hemorrhage on CT scan was correlated with a CPSS of ”1.

The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and negative predictive value of each of facial asymmetry, arm drift and speech disturbance were calculated individually, in pairs and all together using standard formulae.

Data were collected in a preformatted questionnaire, and statistical analysis was done on Microsoft Excel Professional Plus 2013, Version 15.0.4719.1000 (2012 Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA).

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee and written informed consent was obtained from all study subjects.

RESULTS

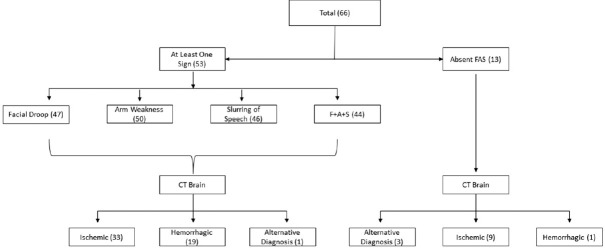

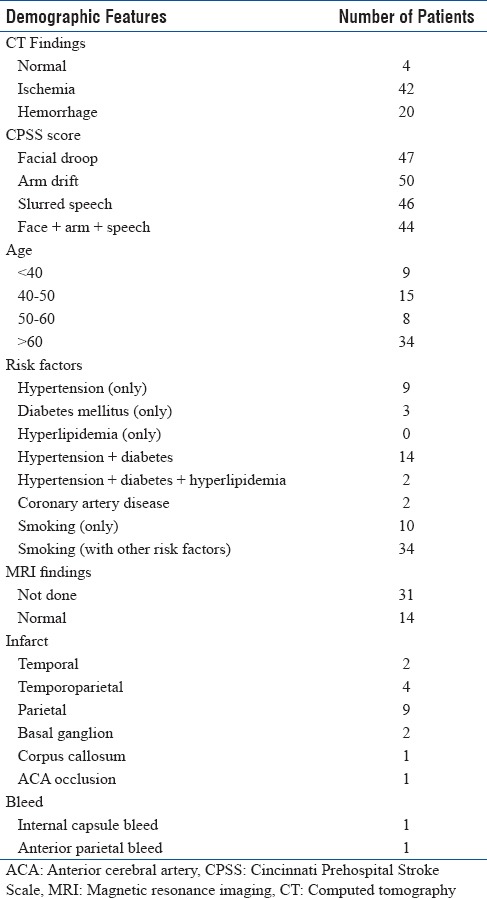

A total of 66 suspected stroke patients were enrolled. 62 (93%) patients had a stroke confirmed on CT scan. Ischemic stroke was seen in 42 (67%) of the scans [Figure 1]. The remaining patients were admitted by the neurology department for further evaluation and follow-up magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and carotid/vertebral artery Doppler scans [Table 1].

Figure 1.

Correlation of Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale with computed tomography brain scan findings

Table 1.

Patient demographics

Out of 53 patients that presented with at least one sign, the EMS personnel were able to identify all patients, thereby diagnosing them early. The average time taken from onset of symptoms to presentation to the ED was 3.45 h (range 1.15 h to 18 h).

Four patients presented with altered mental status which made us suspect a possible stroke (as the CPSS could not be assessed, it was taken as 0). They had alternative diagnoses such as meningioma, metabolic encephalopathy, and glioma.

Surprisingly, none of the patients admitted during the study was diagnosed with a transient ischemic attack as every patient that presented with a score ≥1 had a CT scan abnormality.

Of the confirmed stroke patients, 47 (71%) had Facial Droop, 50 (80%) had Arm Drift, and 46 (74%) had Slurred Speech. All three features were present in 44 (70%) of confirmed stroke patients. Only 7 (11%) patients had abnormal CT scans with the absence of any of these three clinical signs (CPSS = 0). All CT scan results were confirmed using a radiologist's report. The Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of the scores in correlation to abnormality on CT Scans is given in Table 2.

Table 2.

The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of the scores

DISCUSSION

A gold standard is defined as “A thing of superior quality which serves as a point of reference against which other things of its type may be compared.” The current gold standard in the diagnosis of stroke is an MRI Scan.[5] However, unfortunately, it has its pitfalls such as being time-consuming, expensive, and unavailable at all centers. Another pitfall with an MRI scan is that an early hemorrhagic stroke cannot be easily detected and most scans require a trained radiologist to interpret.

A much quicker alternative is the CT scan which is why it was used as the standard in this study. As its use is growing more and more common every day, it does not necessarily require a radiologist to interpret when an obvious abnormality is present. Most emergency physicians are comfortable reading a CT scan, and this helps to promptly begin an appropriate treatment or referral from the ED. A study performed in Tehran, Iran by Dolatabadi et al. found that the number of wrong interpretations by an emergency physician were very few and if anything, EP's tended to over-interpret![6]

In time-sensitive conditions such as a stroke, early detection is the cornerstone of treatment. Further, interventions are only planned after an appropriate imaging is obtained. For example, antiplatelets such as aspirin cannot be commenced in a hemorrhagic stroke, and blind administration can have deleterious effects.

This is where prehospital detection is extremely important so that the patient can be fast-tracked to the closest facility where appropriate care may be available. The CPSS is very similar to the FAST, the only difference being that the FAST also includes “Time of onset” as a score. Several studies have been published comparing the agreement of paramedic and physician recorded neurological signs in the FAST and have reported almost a 90% correlation.[7] We attempted to compare the CPSS with an imaging modality to see if it can be incorporated in our prehospital protocols.

A high sensitivity rules out a diagnosis and a high specificity rules in a diagnosis. PPV is the probability that subjects with a positive screening test truly have the disease. Negative predictive value is the probability that subjects with a negative screening test genuinely do not have the disease.

The confidence interval in this context is the probability of a positive result (score ≥1 on CPSS) actually detecting a stroke and higher the percentage and narrower the confidence interval (CI), the higher the probability.

From our data, we found that the CPSS had a sensitivity (both, individually and combined) of 75%–80% with an almost 100% PPV (CI– 90%–100%). Combined, it showed a specificity of 100%, and individually, except for Arm Drift showing 75%, all other parameters showed a specificity of 100% but with a wide CI of 20%–100% and a negative predictive value of around 20%, which is very low.

The study done by Kothari et al. in 1999 showed a sensitivity and specificity of 66% and 87%, respectively, in identifying a stroke patient.[8] Our results differ possibly because ours is a regional stroke center where by the time patients arrive, majority have an evolved stroke with gross focal neurological deficit. Another possible reason is that since there is a lack of awareness/education about stroke and “The Window Period,” many patients wait at home for their symptoms to resolve on their own,[9,10] causing a delay in reaching a facility capable of providing the care that they require.

As all patients with at least one sign of FAST were identified by the EMS personnel in the prehospital setting using CPSS score, this demonstrates that the score can be used in the Indian prehospital setting as an effective method for early detection of stroke. Owing to the simplicity of the score and as it was effectively implemented in our ED, this shows that it can be easily replicated in newer, developing ED's, and EMS systems in India.

Limitations

A major limitation was that since this is a tertiary care center, most of the patients are either already diagnosed or already have dense hemiparesis before arrival to the hospital. Lack of awareness in the primary and some secondary care centers regarding standard stroke protocols causes a delay in identification and management of patients. In addition, public awareness regarding the identification of emergencies and helpline numbers for prehospital services is lacking.

CONCLUSION

The CPSS showed a high PPV, meaning it can effectively confirm stroke as a differential diagnosis. However, the low negative predictive value does not exclude stroke as a diagnosis. As a prehospital screening tool, it can be extremely useful as any diagnosis is only provisional until confirmed by an appropriate investigation in a hospital.

The score was never meant to be a standard test for diagnosis of stroke, but it is extremely simple to perform and teach. As interuser variability is low, it could be included in teaching programs such as basic life support which is becoming increasingly popular, among the layperson, as awareness regarding cardiac arrest improves.

The Indian prehospital setup is still in a developing phase, and paramedics are not allowed to treat patients outside the hospital. Knowledge of this score and appropriate employment will aid them in making an early diagnosis and referring patients to an appropriate center to facilitate early imaging and intervention. Our study showed that EMS personnel found the scoring system easy to use and this shows that the CPSS can be used even in the developing prehospital care setting or in newly formed EDs.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP., Jr Bruno A, Connors JJ, Demaerschalk BM, editors. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44:870–947. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e318284056a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kidwell CS, Starkman S, Eckstein M, Weems K, Saver JL. Identifying stroke in the field. Prospective validation of the Los Angeles Prehospital Stroke Screen (LAPSS) Stroke. 2000;31:71–6. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen S, Sun H, Lei Y, Gao D, Wang Y, Wang Y, et al. Validation of the Los Angeles pre-hospital stroke screen (LAPSS) in a Chinese urban emergency medical service population. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70742. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roy N, Murlidhar V, Chowdhury R, Patil SB, Supe PA, Vaishnav PD, et al. Where there are no emergency medical services-prehospital care for the injured in Mumbai, India. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2010;25:145–51. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00007883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birenbaum D, Bancroft LW, Felsberg GJ. Imaging in acute stroke. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:67–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arhami Dolatabadi A, Baratloo A, Rouhipour A, Abdalvand A, Hatamabadi H, Forouzanfar M, et al. Interpretation of computed tomography of the head: Emergency physicians versus radiologists. Trauma Mon. 2013;18:86–9. doi: 10.5812/traumamon.12023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nor AM, McAllister C, Louw SJ, Dyker AG, Davis M, Jenkinson D, et al. Agreement between ambulance paramedic- and physician-recorded neurological signs with Face Arm Speech Test (FAST) in acute stroke patients. Stroke. 2004;35:1355–9. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000128529.63156.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kothari RU, Pancioli A, Liu T, Brott T, Broderick J. Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale: Reproducibility and validity. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33:373–8. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70299-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pandian JD, Jaison A, Deepak SS, Kalra G, Shamsher S, Lincoln DJ, et al. Public awareness of warning symptoms, risk factors, and treatment of stroke in Northwest India. Stroke. 2005;36:644–8. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000154876.08468.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pandian JD, Kalra G, Jaison A, Deepak SS, Shamsher S, Singh Y, et al. Knowledge of stroke among stroke patients and their relatives in Northwest India. Neurol India. 2006;54:152–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]