Highlights

-

•

Intrahepatic malignant mesotheliomas are exceedingly rare and have nonspecific symptoms.

-

•

Unlike malignant peritoneal mesotheliomas, the intrahepatic variant is rarely associated with asbestos exposure.

-

•

The diagnosis may be confirmed preoperatively using axial imaging and immunohistochemical staining.

-

•

Liver resection with negative margins including a rim of involved diaphragm is the mainstay of treatment.

Keywords: Intrahepatic mesothelioma, Liver tumors, Liver resection, Diaphragm resection

Abstract

Introduction

Primary Intrahepatic mesotheliomas are malignant tumors arising from the mesothelial cell layer covering Glisson's capsule of the liver. They are exceedingly rare with only fourteen cases reported in the literature. They have nonspecific signs and symptoms and need a high index of suspicion and an extensive workup prior to surgery. Surgery remains the mainstay of treatment.

Presentation of case

48 year old male presented with a 3 months history of abdominal pain, productive cough, anemia and weight loss. He had no history of asbestos exposure. A computed tomography scan and magnetic resonance study demonstrated a heterogeneous subscapular mass within the dome of the right hepatic lobe measuring 11.3 × 6.1 cm involving the diaphragm. Combined resection of the liver and diaphragm was performed to achieve negative margins. Pathology demonstrated an epithelioid necrotic intrahepatic mesothelioma that stained positive for calretinin, CK AE1/AE3, WT-1, D2-40 and CK7.

Discussion

Primary intrahepatic mesotheliomas originate from the mesothelial cells lining Glisson's capsule of the liver. They predominantly invade the liver but may also abut or involve the diaphragm. Surgery should include a diagnostic laparoscopy to rule out occult disease or diffuse peritoneal mesothelioma. Complete resection with negative margins should be attempted while maintaining an adequate future liver remnant. Attempts at dissecting the tumor off the involved diaphragm will result in excessive bleeding and may leave residual disease behind.

Conclusion

Intrahepatic mesotheliomas are rare peripherally-located malignant tumors of the liver. They require a high index of suspicion and a comprehensive workup prior to operative intervention.

1. Introduction

Malignant mesothelioma is a rare neoplasm of mesothelial cells arising most frequently in the pleura or peritoneum and less frequently in the liver [1]. Eighty percent of cases are pleural in origin and are related to asbestos exposure [2]. Peritoneal malignant mesothelioma usually affects the liver through hematogenous spread at advanced stages. Apparent direct invasion of the liver is rare as this tumor has a locally-expansive rather than infiltrative growth pattern [3]. Primary intrahepatic mesotheliomas arising from the mesothelial cells of the Glissonian capsule are exceedingly rare and are difficult to diagnose [1].

Most malignant mesotheliomas grow widely over the serosal membrane surfaces and eventually encase organs surrounding the involved site [4]. Less commonly, mesotheliomas have a localized presentation and appear as a well-circumscribed tumor with the microscopic appearance of diffuse malignant mesothelioma [4]. These can be difficult to differentiate from primary intra-hepatic tumors as both tumors can involve the diaphragm.

Some authors believe that primary intrahepatic mesotheliomas originate from mesothelial cells of Glisson’s capsule which subsequently invade the liver [4]. Others believe that Glisson’s capsule consists of collagen fibers, fibroblasts and small blood vessels and has no mesothelial cells of its own, suggesting that intrahepatic mesotheliomas are simply localized peritoneal malignancies [5]. Mesothelial cells cover the parietal walls of cavities and the surfaces of visceral organs as well. In fact, mesothelial cells are easily recognized covering Glisson’s capsule in liver sections under the microscope [6]. They play an active role in liver development, fibrosis and regeneration [7]. It is our understanding that these cells are the origin of intrahepatic mesotheliomas. Primary intrahepatic mesotheliomas originate and are therefore largely based in the liver, may abut or involve the diaphragm, and demonstrate no diffuse spread.

The differential diagnosis should include other primary and secondary liver neoplasms such as hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma and adenocarcinoma from a known or unknown site [1]. The presentation is non-specific and the preoperative evaluation should include tumor markers, imaging studies and a biopsy to help establish the diagnosis. Surgery is the mainstay of treatment for localized disease. The nonsurgical therapeutic options are very limited. Radiation is only feasible for local tumor control and multimodality treatments with chemotherapy can often only achieve partial remission [5], [8]. We present a case of primary intrahepatic mesothelioma, review the literature and summarize the presentation and management of this rare tumor. The work has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [9].

2. Case presentation

Forty-eight year old male with a remote history of alcohol abuse presented to the emergency department with a 3-months history of right upper quadrant pain, productive cough and a forty pound weight loss. He had no history of asbestos exposure.

His blood work demonstrated a white blood cell count of 8.7 k/ul, hemoglobin of 8.2 mg/dl and a platelet count of 585 k/ul. He had an albumin of 3.3 mg/dl, aspartate transaminase of 41 IU/L, alanine transaminase of 30 IU/L, an elevated alkaline phosphatase of 318 IU/L, a bilirubin of 0.6 mg/dl and a normal coagulation profile. Alpha-fetoprotein and carbohydrate antigen 19.9 were within normal limits.

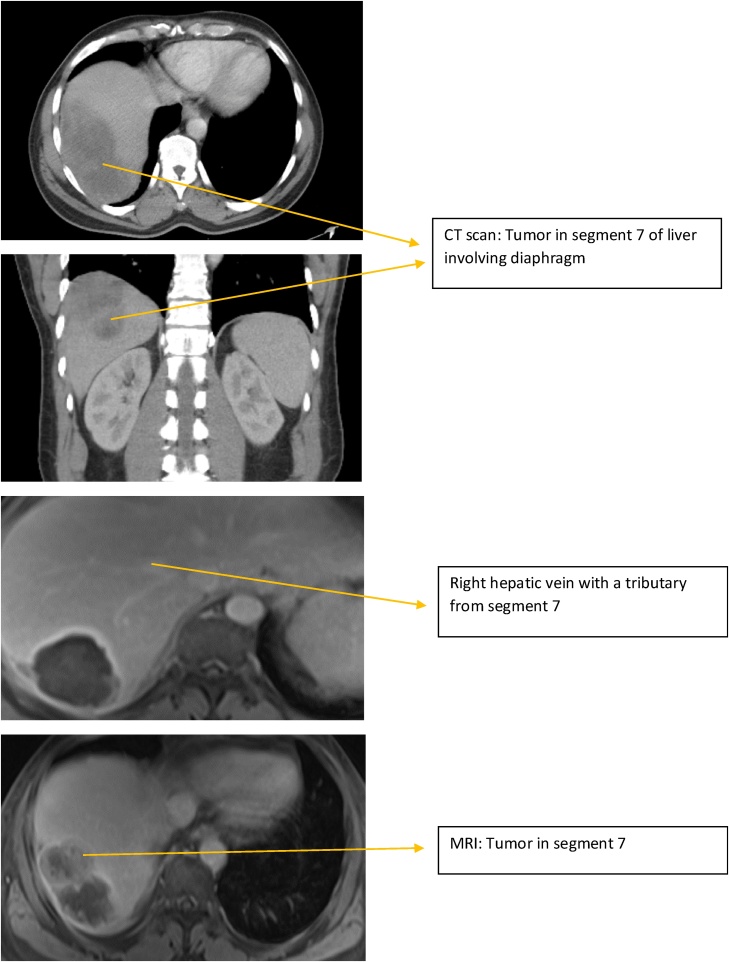

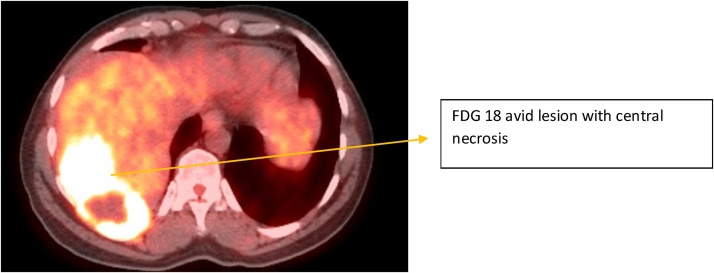

A chest X-ray demonstrated a right-sided pleural effusion and a computed tomography scan and magnetic resonance study demonstrated a complex, heterogeneous subscapular lobulated mass within the dome of the right hepatic lobe measuring 11.3 × 6.1 cm involving the diaphragm (Fig. 1). A positron emission tomography scan was performed to rule out distant metastases and showed a localized fluorodeoxyglucose-avid lesion in segment seven of the liver with central necrosis and no distant spread (Fig. 2). Ultrasound guided thoracentesis was negative for malignant cells and a CT-guided core needle biopsy demonstrated a sarcomatoid carcinoma versus a mesothelioma.

Fig. 1.

CT and MRI images of the tumor.

Fig. 2.

PET scan results.

He was taken to the operating room and a diagnostic laparoscopy was performed which did not demonstrate any evidence of occult malignancy. A modified Makuuchi incision was made and the liver was mobilized by taking down the falciform ligament to the vena cava and dividing the left triangular ligament. The right liver was palpated and a large tumor originating from segment seven was noted invading the diaphragm. The right triangular ligament was approached at its caudal extent, while the diaphragm was mobilized off the hepatic vein confluence and segment eight of the liver. This allowed us to isolate the diaphragm involved by tumor. The diaphragm was incised with a 1 cm grossly negative margin using electrocautery, leaving the involved diaphragm adherent to segment seven.

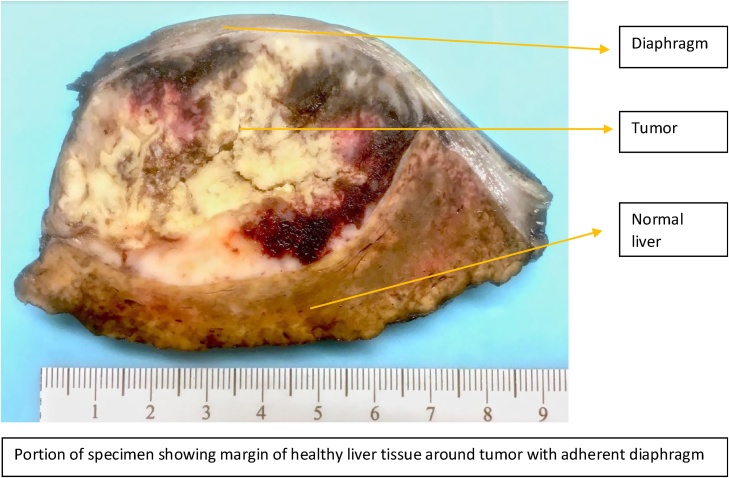

A complete intraoperative liver ultrasound was performed and a transection margin along the right hepatic vein was marked with electrocautery. A Pringle maneuver was performed lasting 15 min and the liver was resected using the two-surgeon technique [10]. A Cavitron Ultrasonic Surgical Aspirator (CUSA, Valleylab, Boulder, CO) and saline-linked electrocautery were used. An open cholecystectomy was performed and an air cholangiogram did not show any bile leak. The diaphragm was then closed using interrupted horizontal mattress sutures (0-Prolene of pledgets) and a chest tube and abdominal drain were placed. The surgery lasted 230 min and the estimated blood loss was 350 ml. Specimen was sent to pathology for margins and were negative (Fig. 3). Patient was discharge on postoperative day 4 after removal of his chest tube and abdominal drain.

Fig. 3.

Specimen.

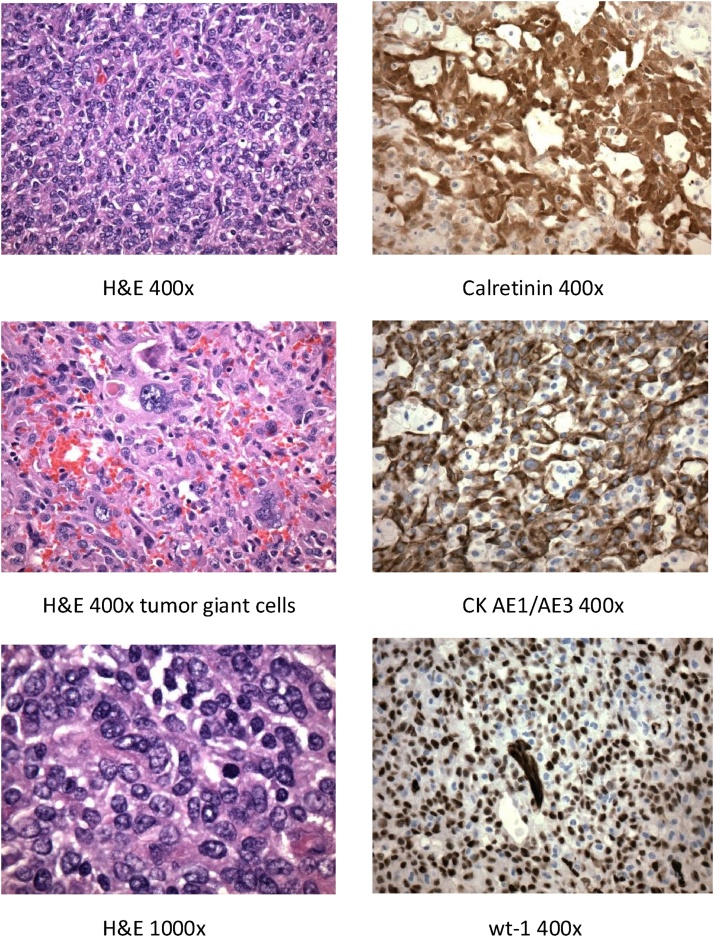

Pathology demonstrated a malignant 10 cm × 7 cm × 5.5 cm intrahepatic, predominantly epithelioid, mesothelioma. It had extensive necrosis (90%) and all margins were negative. Malignant cells did extend, but did not invade, the skeletal muscle of the involved diaphragm. The tumor stained positive for calretinin, CK AE1/AE3, WT-1, D2-40 and CK7 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Microscopic evaluation of tumor.

Tumor positive for Calretinin, CK AE1/AE3, WT-1, D2-40 and CK7

3. Discussion and literature review

Primary intrahepatic mesotheliomas are extremely rare and have a nonspecific presentation. Pain and weight loss are common. Fever can occur secondary to tumor necrosis and the lesion can be confused with a hepatic abscess. Irritation of the diaphragm can lead to a cough.

Although difficult, it is important to establish the diagnosis preoperatively using imaging studies and tissue biopsies as metastatic liver lesions usually need chemotherapy prior to surgical intervention. On axial imaging, intrahepatic mesotheliomas are typically heterogeneous masses with multiple fluid-containing cystic areas, extensive septations and hemorrhage as was seen in this case. They are usually located peripherally and invade deeper into the liver as they continue to grow.

Surgery should include a diagnostic laparoscopy to rule out occult disease or diffuse peritoneal mesothelioma. Complete resection with negative margins should be attempted while maintaining an adequate future liver remnant. Attempts at dissecting the tumor off the involved diaphragm will result in excessive bleeding and may leave residual disease behind. It is therefore important to resect the involved area of the diaphragm leaving it adherent to the tumor. This technique allows for better mobilization of the right lobe of the liver while maintaining negative margins and reducing blood loss.

Three different characteristic histologic patterns can be discriminated based on routine hematoxylin-eosin staining: epithelioid, sarcomatoid and biphasic [2]. Within the epithelioid category, morphologic variations such as tubulopapillary and solid can be distinguished. High mitotic rate, necrosis, hemorrhage, hyper-cellularity and atypia are signs of malignancy. The typical immunohistochemical features that characterize mesotheliomas are vimentin, cytokeratin, thrombomodulin, calretinin, Wilms’ tumor gene-1 (WT-1) and cytoplasmic D2-40 positivity [11].

The tumor in this case was associated with nonspecific symptoms, demonstrated cystic areas with hemorrhage on imaging studies and had the necessary histologic findings to make the diagnosis of an epithelioid primary intrahepatic mesothelioma. Only 14 cases with this tumor have ever been reported.

A comprehensive literature review of intrahepatic mesotheliomas was performed. A detailed search of relevant publications was conducted using PubMed and MEDLINE and is summarized in Table 1 [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19]. Analysis of this data revealed the following:

Table 1.

Literature review and data analysis.

| Author | Year | Sex | Age | Asbestos exposure | Diameter (cm) |

Anemia | Liver lobe | Peripheral (Subcapsular) | Histologic subtype | Surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kottke-Marchan [12] | 1989 | F | 83 | NR | 15 | NR | L | Y | Spindle cell | Y |

| Imura et al. [13] | 2002 | M | 64 | N | 3.2 | NR | R | Y | Epithelioid | Y |

| Leonardou et al. [14] | 2003 | F | 54 | NR | 16 | NR | R | Y | Epithelioid | Y |

| Di Balasi et al. [15] | 2004 | F | 61 | NR | 10 | NR | R | Y | Epithelioid | Y |

| Gutgemann et al. [16] | 2006 | M | 62 | N | 5.8 | NR | R | Y | Epithelioid | Y |

| Kim et al. [17] | 2008 | M | 53 | N | 13 | R | Y | Biphasic | Y | |

| Sasaki et al. [4] | 2009 | M | 66 | Y | 4.4 | NR | R | Y | Biphasic | Y |

| Bucholz et al. [8] | 2009 | F | 62 | N | 5.8 | NR | R | Y | Epithelioid | Y |

| Inagaki et al. [18] | 2013 | F | 68 | N | 7 | N | R | Y | Epithelioid | N |

| Dong et al. 19 | 2013 | F | 50 | N | Multiple | NR | R/L | Y | Epithelioid | Y |

| Perysinakis et al. [2] | 2014 | M | 60 | N | 8.5 | Y | R | Y | Epithelioid | Y |

| Serter et al. [11] | 2015 | F | 56 | N | 15 | Y | R | Y | Epithelioid | Y |

| Serter et al. [11] | 2015 | M | 66 | N | Multiple | Y | R/L | Y | Biphasic | Y |

| Ali et al. [1] | 2016 | F | 41 | N | 24 | Y | R | Y | Biphasic | Y |

| Ismael et al | 2018 | M | 60 | N | 11.3 | Y | R | Y | Epithelioid | Y |

M – Male.

F – Female.

Y – Yes.

N – No.

NR – Not Recorded.

R – Right.

L – Left.

46.7% of patients with intrahepatic mesotheliomas were male. The mean age at presentation was 60.4 (41–83 years). The majority of patients had no history of asbestos exposure. Pre-operative anemia was a common finding affecting at least one third of patients (5/15). The mean diameter of the tumor was 10.7 cm (3.2–24 cm). Two-thirds (66.7%) of the cases demonstrated epithelioid histology, while the rest were biphasic and one was sarcomatoid. Surgery was the mainstay of treatment.

These tumors have no sex preference and usually occur in the fifth decade of life in the right lobe of the liver. They are subcapsular and present late as evident by the large tumor size at diagnosis. Although asbestos exposure is associated with 70% of mesothelioma cases [20], this relationship does not hold true for intrahepatic mesotheliomas. Anemia was noted in at least one third of patients and in the majority of cases when the hemoglobin level was reported. This is a new and important association and is likely related to intra-lesional hemorrhage.

4. Conclusion

Primary intrahepatic mesotheliomas are rare peripherally-located tumors that are frequently associated with pain, weight loss and anemia secondary to intra-lesional bleeding. Most cases are not related to asbestos exposure. Axial imaging and percutaneous biopsies help confirm and guide therapy. Surgery is the mainstay of treatment. Liver resection should be performed with excision of the involved diaphragm en-bloc to achieve negative margins and avoid spillage.

Conflicts of interest

None of the Authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Sources of funding

None.

Ethical approval

Approval has been given by the University of Texas Northeast ethics committee.

Consent

Written consent has been given.

Author contributions

Hishaam Ismael MD: Literature review and writing the article.

Steven Cox MD: Reviewing and editing the article.

Registration of research studies

None.

Guarantor

Hishaam Ismael MD.

Disclosure

None of the authors have anything to disclose.

Contributor Information

Hishaam Ismael, Email: Hishaam.Ismael@uthct.edu.

Steven Cox, Email: Steven.Cox@uthct.edu.

References

- 1.Ali A.H., Khalife M., El Nounou G. Giant primary malignant mesothelioma of the liver: a case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2017;30:58–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perysinakis I., Nixon A.M., Spyridakis I. Primary intrahepatic malignant epithelioid mesothelioma. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2014;5(12):1098–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2014.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagata S., Tomoeda M., Kubo C. Malignant mesothelioma of the peritoneum invading the liver and mimicking metastatic carcinoma: a case report. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2011;207(6):395–398. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sasaki M., Araki I., Yasui T. Primary localized malignant biphasic mesothelioma of the liver in a patient with asbestosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2009;15(5):615–621. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Su S., Zheng Y., Chen Y. Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma with hepatic involvement: a single institution experience in 5 patients and review of the literature. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2016;2016:6242149. doi: 10.1155/2016/6242149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lua I., Asahina K. The role of mesothelial cells in liver development: injury and regeneration. Gut Liver. 2016;10(2):166–176. doi: 10.5009/gnl15226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y., Wang J., Asahina K. Mesothelial cells give rise to hepatic stellate cells and myofibroblasts via mesothelial-mesenchymal transition in liver injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110(6):2324–2329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214136110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchholz B.M., Gutgemann I., Fischer H.P. Lymph node dissection in primary intrahepatic malignant mesothelioma: case report and implications for diagnosis and therapy. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2009;394(6):1123–1130. doi: 10.1007/s00423-009-0476-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A. The SCARE Statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aloia T.A., Zorzi D., Abdalla E.K. Two-surgeon technique for parenchymal transection of the noncirrhotic liver using saline-linked cautery and ultrasonic dissection. Ann. Surg. 2005;242(2):172–177. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000171300.62318.f4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Serter A., Buyukpinarbasili N., Karatepe O., Kocakoc E. An unusual liver mass: primary malignant mesothelioma of the liver. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2015;33:102–106. doi: 10.1007/s11604-014-0379-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kottke-Marchant K., Hart W.R., Broughan T. Localized fibrous tumor (localized fibrous mesothelioma) of the liver. Cancer. 1989;1:1096–1102. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890901)64:5<1096::aid-cncr2820640521>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imura J., Ichikawa K., Takeda J. Localized malignant mesothelioma of the epithelial type occurring as a primary hepatic neoplasm: a case report with review of the literature. APMIS. 2002;110(11):789–794. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2002.t01-1-1101102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leonardou P., Semelka R.C., Kanematsu M. Primary malignant mesothelioma of the liver: MR imaging findings. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2003;21:1091–1093. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(03)00197-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Blasi A., Boscaino A., De Dominicis G. Multicystic mesothelioma of the liver with secondary involvement of peritoneum and inguinal region. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2004;12:87–91. doi: 10.1177/106689690401200116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gutgemann I., Standop J., Fischer H.P. Primary intrahepatic mesothelioma of the epithelioid type. Virchows Arch. 2006;1:655–658. doi: 10.1007/s00428-006-0175-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim D.S., Lee S.G., Jun S.Y. Primary malignant mesothelioma developed in liver. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;55:1081–1084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inagaki N., Kibata K., Tamaki T. Primary intrahepatic malignant mesothelioma with multiple lymphadenopathies due to non-tuberculous mycobacteria: a case report and review of the literature. Oncol. Lett. 2013;6:676–680. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong A., Dong H., Zuo C. Multiple primary hepatic malignant mesotheliomas mimicking cystadenocarcinomas on enhanced CT and FDG PET/CT. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2014;39:619–622. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e31828da61d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDonald J.C., McDonald A.D. Asbestos and carcinogenicity. Science. 1990;249(4971):844. doi: 10.1126/science.2168090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]