Highlights

-

•

Patients with small bowel adenocarcinoma tend to present with non-specific symptoms.

-

•

The median time between onset of symptoms and diagnosis is 2–8 months.

-

•

Disease is often advanced by the time of diagnosis (stage IV 32%).

-

•

Tumour markers are not useful in the diagnosis of small bowel adenocarcinomas.

Keywords: Small intestine, Adenocarcinoma, Symptoms, Investigative techniques, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Small bowel malignancies are rare and often present with non-specific symptoms. Because of this, diagnosis of small bowel malignancies is often missed.

Presentation of case

71-year-old male presented with a four-week history of right iliac fossa pain and loss of weight. Laboratory tests showed a raised C-reactive protein, but all other pathology results and tumour-associated antigens were normal. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen demonstrated an inflammatory mass extending laterally into the pelvic wall. The patient underwent an elective laparotomy and resection of the small bowel tumour. Intra-operative findings included a small bowel tumour adherent to two loops of small bowel. Histology demonstrated a 50 mm poorly differentiated mucinous adenocarcinoma of the terminal ileum.

Discussion

Clinical presentation of small bowel adenocarcinoma is often non-specific, which leads to a delay in diagnosis. As a result, disease is often advanced by the time of diagnosis. Upper and lower endoscopy is useful in detecting tumours in the duodenum and terminal ileum. Video capsule endoscopy allows visualisation of the entire small bowel mucosa. Enteroscopy can also be used to obtain biopsies and perform therapeutic interventions. CT is able to detect abnormalities in 80% of patients, while CT and MR (magnetic resonance) enteroclysis give better visualisation of the mucosa and mural thickness. Surgical exploration may be indicated in patients with a strong clinical suspicion.

Conclusion

In conclusion, small bowel malignancies are rare and clinicians are reminded to have a high index of suspicion for small bowel malignancies in patients who present with non-specific abdominal symptoms.

1. Introduction

The incidence of small bowel malignancy is rare worldwide, with a global incidence of 0.3–1.5 cases per 100,000 population [1]. In the United States, small bowel cancers account for 0.6% of total cancer cases and 3.3% of gastrointestinal malignancies [2]. The prevalence of small bowel cancer increases with age, with a mean age at diagnosis of 60 years.

The four main histological types of small bowel cancer are adenocarcinomas (30–40%), carcinoid tumours (35–42%), lymphomas (15–20%) and sarcomas (10–15%) [3]. The most common location for small bowel adenocarcinoma is in the duodenum (57%), followed by the jejunum (29%) and the ileum (10%) [4].

Risk factors for small bowel adenocarcinoma include Crohn’s disease, coeliac disease, adenoma of the small bowel, familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS), cigarette smoking and obesity [3].

Patients with small bowel adenocarcinoma tend to present with non-specific symptoms. Given the varied clinical presentation and rarity of the disease, symptoms are often misdiagnosed. Therefore, the diagnosis of small bowel adenocarcinoma tends to be made at an advanced stage.

Here we describe a case of small bowel adenocarcinoma in a male patient. This patient presented to a rural hospital in Victoria, Australia, with abdominal pain and weight loss. This case highlights the highly unpredictable presentation of small bowel adenocarcinoma, and acts as a reminder for clinicians to consider small bowel malignancies in patients with non-specific abdominal symptoms.

This case report has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [5].

2. Presentation of case

A 71-year-old male presented to a rural hospital in May 2017 with a four-week history of right iliac fossa pain associated with a thirteen-kilogram weight loss. This was on a background of an open right hemicolectomy nine years ago for an inflammatory mass secondary to caecal diverticulitis. His co-morbidities included hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia.

Physical examination revealed a soft abdomen with a fullness in the right iliac fossa. Laboratory tests showed a raised C-reactive protein (162), however all other pathology results including white cell count were within normal limits. Tumour-associated antigens were not elevated (carcino-embryonic antigen (CEA) 3.2, carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) 23 and alpha fetoprotein (AFP) less than 1). Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen demonstrated mural thickening in the terminal ileum with proximal small bowel dilatation. This was associated with a 6 cm inflammatory mass extending laterally into the pelvic wall. The patient was admitted for conservative management and treated with intravenous antibiotics. Subsequently, his symptoms improved and he was discharged on oral antibiotics.

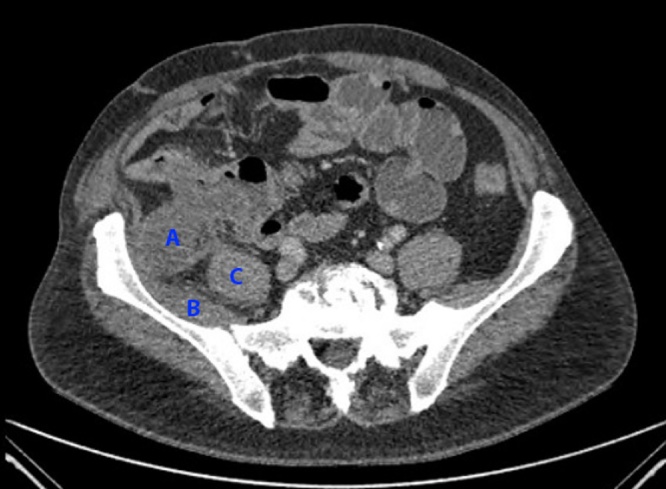

An outpatient CT enteroclysis demonstrated a low density, minimally enhancing soft tissue mass arising from the posterior wall of the distal ileum (Fig. 1). It projected posteriorly to lie against the iliacus muscle. The patient underwent an elective laparotomy and resection of the small bowel tumour. Intra-operative findings included a mucus-containing small bowel tumour adherent to two loops of small bowel, penetrating deeply into psoas and iliacus, and involving the gonadal vessels.

Fig. 1.

Soft tissue mass arising from the posterior wall of the distal ileum, lying against the iliacus muscle. A = small bowel tumour; B = iliacus muscle; C = psoas muscle.

Histology demonstrated a 50 mm poorly differentiated mucinous adenocarcinoma of the terminal ileum (stage pT3N0). There was no lymphovascular or perineural invasion. Four lymph nodes were identified which were clear of tumour. The patient was referred for adjuvant chemotherapy.

3. Discussion

Diagnosis of small bowel adenocarcinoma is often difficult due to the rarity of these lesions, the variable nature of clinical presentation and the lack of a specific diagnostic pathway. The clinical presentation of small bowel adenocarcinoma is often non-specific, with abdominal pain being the most common symptom. In a retrospective study with 491 cases of small bowel adenocarcinoma between 1970 and 2005, the most common presenting symptoms were abdominal pain (43%), nausea and vomiting (16%), anaemia (15%), gastrointestinal bleeding (7%), jaundice (6%), weight loss (3%) and other/no symptoms (9%) [4]. Because symptoms are often vague, there is usually a delay in diagnosis, with the median time between onset of symptoms and a correct diagnosis of approximately 2–8 months [6]. As a result, disease is often advanced by the time of diagnosis (stage 0 3%, stage I 12%, stage II 27%, stage III 26%, stage IV 32%) [7].

There is no diagnostic protocol for the diagnosis of small bowel adenocarcinoma, and a high index of suspicion is essential for early diagnosis and treatment. Standard upper endoscopy may be adequate for duodenal tumours, while lower endoscopy is useful for excluding colonic malignancies and may detect tumours in the terminal ileum. Video capsule endoscopy is the method of choice in patients with suspected small bowel bleeding as it allows visualisation of the entire small bowel mucosa. Push enteroscopy and double-balloon enteroscopy can be used to visualise the small bowel, obtain biopsy samples and perform therapeutic interventions. However, these procedures are invasive and not widely available.

CT scan is usually the first form of investigation for non-specific abdominal symptoms. It is able to detect abnormalities in 80% of patients with small bowel tumours [8]. CT and magnetic resonance enteroclysis allow for better visualisation of gastrointestinal mucosa, mural thickness and mesenteric vasculature. 219 patients with clinical suspicion for small bowel cancers and normal upper and lower endoscopy underwent CT enteroclysis, and found that CT enteroclysis had an overall sensitivity and specificity of 84.7% and 96.9% respectively in identifying small bowel lesions [9].

Surgical exploration may be indicated in patients with a strong clinical suspicion of small bowel pathology and negative radiological and endoscopic findings. Tumour markers are not sensitive or specific for the diagnosis of small bowel adenocarcinoma.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, small bowel malignancies are rare and patients tend to have vague symptoms. This case report serves to remind clinicians to have a high index of suspicion for small bowel malignancies in patients who present with non-specific abdominal symptoms.

Study design

This is a case study which is retrospective in design involving a single centre.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they do not have any personal conflicts of interest.

Funding

No external funding was used for this study.

Ethical approval

Being a case report, this study is exempt from prior evaluation by an ethics committee.

Consent

Written consent has been obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying figures. A copy of the written consent is available for review on request.

Author contribution

Joyce Ma – data collection, writing paper.

Paul Strauss – study concept, study design.

Registration of research studies

Guarantor

Paul Strauss.

Contributor Information

Joyce Lok Gee Ma, Email: joyce.ma@austin.org.au.

Paul Norman Strauss, Email: paul.strauss@cghs.com.au.

References

- 1.Forman D., Bray F., Brewster D.H., Gombe Mbalawa C., Kohler B., Pineros M. IARC Scientific Publications No. 164. IARC; Lyon: 2014. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents Vol. X. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R.L., Jema A. Cancer statistics 2012. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pan S.Y., Morrison H. Epidemiology of cancer of the small intestine. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2011;3(3):33–42. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v3.i3.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halfdanarson T.R., McWilliams R.R., Donohue J.H., Quevedo J.F. A single institution experience with 491 cases of small bowel adenocarcinoma. Am. J. Surg. 2010;199:797–803. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., for the SCARE Group The SCARE Statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lech G., Korcz W., Kowalcayk E., Slotwinski R., Slodkowski M. Primary small bowel adenocarcinoma: current view on clinical features, risk and prognostic factors, treatment and outcome. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2017;52(11):1194–1202. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2017.1356932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howe J.R., Karnell L.H., Menck H.R., Scott-Conner C. The American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer and the American Cancer Society. Adenocarcinoma of the small bowel: review of the National Cancer Data Base, 1985-1995. Cancer. 1999;86(12):2693. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991215)86:12<2693::aid-cncr14>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laurent F., Raynaud M., Biset J.M., Boisserie-Lacroix M., Grelet P., Drouillard J. Diagnosis and categorization of small bowel neoplasms: role of computed tomography. Gastrointest. Radiol. 1999;16(2):115. doi: 10.1007/BF01887323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pilleul F., Penigaud M., Milot L., Saurin J.C., Chayvialle J.A., Valette P.J. Possible small-bowel neoplasms: contrast-enhanced and water-enhanced multidetector CT enteroclysis. Radiology. 2006;241(3):796. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2413051429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]