Abstract

Purpose of the Study:

To describe the experience of recruiting, training, and retaining retired senior volunteers (RSVs) as interventionists delivering a successful reminiscence and creative activity intervention to community-dwelling palliative care patients and their caregivers.

Design and Methods:

A community-based participatory research framework involved Senior Corps RSV programs. Recruitment meetings and feedback groups yielded interested volunteers, who were trained in a 4-hr session using role plays and real-time feedback. Qualitative descriptive analysis identified themes arising from: (a) recruitment/feedback groups with potential RSV interventionists; and (b) individual interviews with RSVs who delivered the intervention.

Results:

Themes identified within recruitment/feedback groups include questions about intervention process, concerns about patient health, positive perceptions of the intervention, and potential characteristics of successful interventionists. Twelve RSVs achieved 89.8% performance criterion in treatment delivery. Six volunteers worked with at least one family and 100% chose to work with additional families. Salient themes identified from exit interviews included positive and negative aspects of the experience, process recommendations, reactions to the Interventionist Manual, feelings arising during work with patient/caregiver participants, and personal reflections. Volunteers reported a strong desire to recommend the intervention to others as a meaningful volunteer opportunity.

Implications:

RSVs reported having a positive impact on palliative care dyads and experiencing personal benefit via increased meaning in life. Two issues require further research attention: (a) further translation of this cost-effective mode of treatment delivery for palliative dyads and (b) further characterization of successful RSVs and the long-term impact on their own physical, cognitive, and emotional functioning.

Key Words: Translation, Volunteers, Strength-based Intervention, Reminiscence, Creative Activity, Meaning

Increasingly, evidence supports a connection between volunteerism and successful aging (Anderson et al., 2014; Morrow-Howell, Hong, & Tang, 2009). Older adults with more education, higher income, better health and better social engagement are more likely to volunteer (Zedlewski & Schaner, 2006). Frequently, these individuals are motivated by the desire to help others and stay active (Anderson et al., 2014; Okun & Schultz, 2003; Omoto, Synder, & Martino, 2000). Volunteer efforts reflect a monetary value of nearly $175 billion in 2012 (Corporation for National and Community Service, 2012), and volunteering affords positive health benefits to the volunteer (Harris & Thoresen, 2005; Martinez et al., 2006). In a recent review, volunteering has been proposed as a potential health promotion strategy that improves psychosocial, physical, and cognitive functioning in the short term and, potentially, as a means to reduce dementia risk in the long-term (Anderson et al., 2014). Volunteerism among older adults is supported by the National Senior Corps Program, part of the Corporation for National and Community Service, and has been on an upward trend in recent years. In 2013 in the United States, 24.1% of people aged 65 and older volunteered (Anderson et al., 2014).

Remarkably, volunteers have rarely been the focus of training efforts in delivery of simple evidence-based interventions despite clearly articulated calls for new therapeutic delivery modalities to meet community needs for mental health and wellness services (Kazdin & Blase, 2011). Prior research has shown that volunteers may find meaning in working with at-risk populations as compassionate and cost-effective service providers, but they require need-based training to prevent burnout and improve retention (Hiatt & Jones, 2000). Recent work has demonstrated that RSVs can be trained to effectively deliver a reminiscence and creative activity intervention with palliative care patients and their caregivers (Allen et al., 2014).

This study describes the process of RSV recruitment and training using a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach, and the theoretical/conceptual basis for and the essential components of an evidence-based reminiscence and creative activity intervention for community-dwelling palliative care patients and their caregivers delivered by RSVs (Allen et al., 2014). Incorporating trained RSVs as community interventionists using simple therapeutic techniques to prevent and alleviate suffering among older adults and their family caregivers (i.e., dyads) in the community may be one means of translating effective interventions into real-world contexts. Moreover, such community engagement has direct benefits for volunteers (Anderson et al., 2014). Qualitative analysis of interview data during feedback groups of potential volunteers after recruitment meetings revealed several themes that influenced research design. Rich qualitative description of exit interviews with six RSVs who worked with dyads in the community revealed important themes including an increased sense of meaning among volunteers.

Theoretical and Conceptual Basis of Intervention

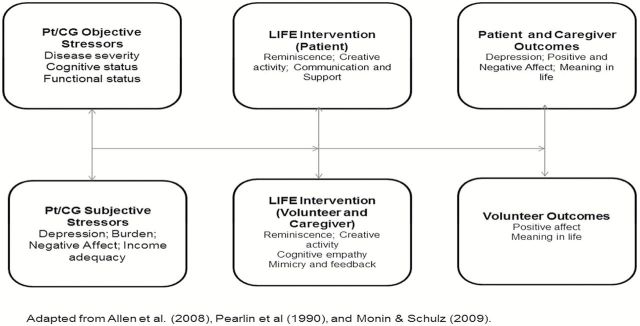

The conceptual model (see Figure 1) that serves as the basis for the Legacy Intervention Family Enactment (LIFE) intervention draws from widely used stress and coping models (Folkman, 1997; Pearlin, Mullan, Semple, & Skaff, 1990) and has been previously described (Allen, Hilgeman, Ege, Shuster, & Burgio, 2008). Briefly, LIFE was designed to harness the power of an individual’s perspective of limited time left to live (Carstensen, Isaacowitz, & Charles, 1999) within palliative patients and their caregivers to promote engagement in meaning-based coping (Folkman, 1997), thereby leading to sustained coping and the experience of positive emotions. This strengths-based intervention model addresses the mediating influence of engagement in the intervention on outcomes for all participants (patients, caregivers, and volunteers).

Figure 1.

Stress process and the LIFE intervention.

Uniqueness or Innovation and Essential Components

Two issues reflect the unique and innovative information provided in this study: (a) further translation of this cost-effective mode of treatment delivery for palliative dyads and (b) qualitative characterization of successful RSVs, suggesting potential mechanisms for long-term impact on their own physical, cognitive, and emotional functioning. First, we propose that further exploration of the LIFE intervention and RSV training program as a translational tool increases the potential for service provision to chronically ill patients and their caregivers in the community. The strengths-based LIFE intervention was designed to combat losses of social belonging and identity by providing companionship and focused attention and activity directed at celebrating the older adult’s lifetime accomplishments. Allen and colleagues (2014) demonstrated the success of training RSVs to engage community-dwelling palliative care dyads through structured interactions focused on singular meaningful activity that is undertaken together. Potential widespread adoption of this training program, however, depends on the ability to recruit and retain RSVs, the issues explored through the current qualitative analysis. Identifying unique characteristics of successful RSV interventionists and highlighting the benefits they experience will facilitate potential replication of the success experienced by our community partners in local senior citizens centers.

Methods

Data were collected between June 2009 and December 2011 with approval from The University of Alabama and the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Boards. Results of the randomized controlled effectiveness trial (NCT02007564) have been previously reported (Allen et al., 2014). The focus of this analysis is to explore the feedback obtained from potential and active RSV LIFE interventionists. Volunteers gave feedback about the project at several points: recruitment/feedback meetings, interventionist training sessions, and individual interviews after completion of work with a patient/caregiver dyad. This stakeholder feedback was essential in the CBPR process in order to provide insight into how the LIFE project could be improved from the RSV perspective as interventionists. Such feedback facilitates further translation of the project and successful implementation and maintenance within partnering organizations. The primary research questions addressed through feedback groups and individual exit interviews were: What were RSVs’ perceptions about the potential and challenges of this volunteer opportunity? After working with dyads, what were RSV’s perceptions of the usefulness of the training received and working with older adults/caregivers during project implementation? What were RSVs’ feelings/beliefs about working with older adults with advanced chronic illness and their caregivers in the community? What did RSVs’ identify as the value of the LIFE intervention and what suggestions did they have for improvement?

What is LIFE?

LIFE is a manualized, three-session combination reminiscence and creative activity intervention that has been effectively delivered to palliative care patients and their family caregivers (Allen et al., 2008; Allen et al., 2014). Similar to Chocinov’s Dignity Therapy (Chochinov et al., 2011; Chochinov, 2012), the LIFE intervention focuses patients’ attention on lifetime accomplishments, relationships, and values, using techniques such as reminiscence and creative activity to facilitate meaning reconstruction. The manual and accompanying workbook consist of: (a) instructions about using the steps of problem solving (D’Zurilla & Nezu, 2007) to decide on a period of life and creative activity project; (b) constructing a project; (c) evaluation of the activity; and (d) an appendix with life review questions for dyads that find generation of stories and a corresponding creative activity project more difficult.

Recruitment of Sites and RSV Participants

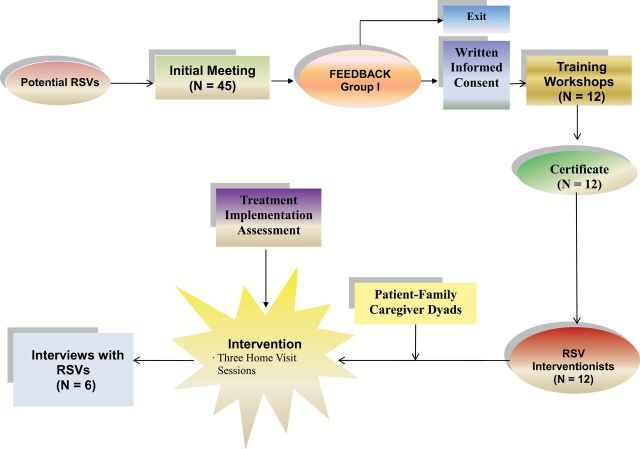

The flow of involvement for RSVs in the LIFE project with associated sample sizes is illustrated in Figure 2. The study team recruited and trained retired senior volunteers (RSVs) in partnership with the RSV programs at FOCUS on Senior Citizens in Tuscaloosa, AL and Positive Maturity in Birmingham, AL. We conducted two meetings with RSV leadership (one in each city), four recruitment sessions and feedback groups with potential RSV LIFE interventionists (two at each site), and three in-depth training sessions for interested volunteers (one in Tuscaloosa and two in Birmingham). RSVs were eligible to become LIFE interventionists if they: (a) had a high school education; (b) read and spoke English; and (c) had a car and drove independently. Prior experience in dealing with advanced chronic or terminal illness was not an eligibility criterion for RSVs. However, RSVs indicated if there was any type of advanced chronic illness they would prefer to avoid when being assigned a patient–caregiver dyad.

Figure 2.

Flow of RSV participants in the LIFE Project.

As reported in Allen and colleagues (2014), palliative care patients were eligible if they: (a) were aged 55 years or older, (b) were living in the community or assisted living, (c) had an advanced illness or combination of chronic illnesses, (d) had a life expectancy less than 24 months, (e) had no more than mild cognitive impairment, (f) received an average of 4hr per week of care from a caregiver, and (g) read and spoke English. Caregivers were nominated by the palliative care patient. Dyads were excluded if the patient was receiving hospice care, if the patient or caregiver had schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, or if a nursing home admission was planned within 3 months.

The interested RSVs were asked to: (a) complete a series of feedback groups and training workshops; (b) work with individuals in the community who have an advanced illness and a family member or friend; (c) complete a few brief surveys and one individual interview at the end of work with each community dyad; and (d) participate in meetings or conference calls with members of the research team as needed. Volunteers received $20 cash remuneration at the end of the project along with $5 mileage reimbursement for each visit to patient/caregiver homes.

RSVs indicated their consent to engage in the feedback session after the recruitment meeting by staying in the room. Written informed consent was obtained from RSVs at training sessions to obtain basic demographic data and scores on treatment delivery assessments. Our goal in this initial study was to recruit RSVs as interventionists, or extensions of the research team, in delivering an intervention to community-dwelling palliative care dyads. Hence, we aimed to minimize RSV participant burden by focusing on qualitative data rather than completion of questionnaires. Therefore, no identifying information was obtained from RSVs who attended the recruitment/feedback meetings and only minimal demographic information was obtained from RSVs at the training workshops.

Recruitment Sessions and Feedback Groups

With the support and presence of RSV administrative staff at both senior centers, recruitment meetings, along with accompanying feedback groups immediately following, were scheduled to discuss the project, ascertain interest in participation and learn about potential reactions to the information presented, and the opportunity to volunteer as a LIFE interventionist. The recruitment session included a presentation by a research team member regarding the background, design, potential benefits for RSVs and intervention dyads, and role of the volunteer interventionist. Samples of completed LIFE activity projects were provided. The presentation evolved for later feedback groups based on feedback from our expert external consultants; this ensured more emphasis on the personal meaningfulness of this particular volunteer opportunity for RSVs.

A semi-structured interview guide was used within each feedback group to gain information from potential LIFE interventionist volunteers. The group discussions were digitally audio-recorded and transcribed by a professional transcriptionist. Additionally, at least one member of the research team recorded field notes during the feedback groups. At the end of the recruitment sessions, attendees were asked to indicate if they wanted to be contacted to participate in the training session in preparation for engagement in the project.

RSV Training in the LIFE Intervention

RSVs who hoped to be trained as a LIFE interventionist signed informed consent and attended one of several 4-hr training workshops held onsite at the senior centers. The training session focused on the first (identification of a LIFE project) and third (evaluation of LIFE) intervention visits and culminated in assessment of the RSV’s role play delivery of intervention session one based on the instruction provided. RSVs were trained to assist dyads in carrying out the construction of the selected LIFE project during the second visit. Additional training addressed how to use the steps of problem solving to identify barriers to progress should the dyad have difficulty in completion of the project.

Using the LIFE Volunteer Interventionist Manual, dyads were engaged in reminiscence and used the six steps of problem solving (D’Zurilla & Nezu, 2007) to identify one targeted aspect of the older adult’s life to be represented in a specific creative activity. The end result would be a legacy project (a completed scrapbook, photo album, cookbook, or detailed audiotapes). As reported in Allen and colleagues (2014), RSVs were carefully trained to monitor dyads’ reactions. If either member of the dyad reacted in a persistently negative manner to the intervention, the dyad activity was discontinued. If the RSV interventionists believed that the emotions or reactions experienced by either member of the dyad were potentially problematic, the interventionists were instructed to contact a member of the research team immediately. Sessions lasted between 60 and 90min, with more time allocated to sessions one and three.

At the end of the training workshop, RSVs engaged in a structured role play paired with a certified professional LIFE interventionist. The RSV assumed the role of the LIFE interventionist, whereas the research staff member assumed the role of the older adult with advanced chronic illness and/or caregiver. If the RSV achieved 80% fidelity in treatment delivery as assessed by the research staff, the RSV received a certificate of completion and certification as a LIFE interventionist at the end of the training session. The average treatment fidelity score achieved by the 12 certified RSVs during training was 89.8%. In the original efficacy trial (Allen et al., 2008), expert professional interventionists achieved an average treatment delivery fidelity score of 91.5%.

Exit Interviews with RSVs Post Treatment Implementation with Community Dyads

All volunteer interventionists were interviewed face-to-face by a member of the research team after all LIFE intervention sessions were completed with a dyad. A semi-structured interview guide addressed the RSV experience, project design and suggested areas for improvement. Major domains included positive and negative aspects of the project, timing/implementation issues, training, interventionist manuals, and recommendations for improvement of training and implementation. All interviews were digitally recorded and later transcribed by a professional transcriptionist.

Qualitative Data Analysis

The transcripts of the feedback groups and individual RSV interviews were analyzed separately. Narratives were analyzed using the descriptive and thematic analysis approaches. According to Sandelowski (2000), qualitative description is the method of choice when straight descriptions of phenomena are desired within a new and exploratory line of inquiry. Thus, the scientific goal was to stay close to the data and to the RSV’s own words and description of events.

Best standards of qualitative methodology that support validity are rigor, trustworthiness and an awareness of reflexivity, credibility, and believability (Thorpe & Holt, 2007). In this study, we increased trustworthiness of findings by directly examining reflexivity, or what the coder brings to the coding of qualitative data, through the use of investigator triangulation. A three-member analysis team with experience and expertize in qualitative methodology (R.S.A., C.B.A., and E.L.C.) independently analyzed transcripts and developed themes. This investigator triangulation or peer review helped to keep investigators’ interpretations in check and supported basic awareness of potential bias although facilitating solid evidence for interpretation of the data. Each transcript was read independently to identify initial themes and subcategories in the text. New themes and refinements to identified ones were considered by the coding team at regularly scheduled research meetings. Discrepancies were infrequent but, when they occurred, were resolved through discussion and consensus. In addition, the analysis team kept detailed notes as part of an audit trail, documenting every step of the research process and analytic decisions (Bradley, Curry, & Kelly, 2007).

Results

RSV Characteristics

A total of 45 RSVs attended a recruitment session to learn more about the LIFE volunteer opportunity. Of the 12 individuals who attended a Tuscaloosa recruitment session and feedback group (all women; 9 Caucasian, 3 African American), four Caucasian women participated in the training workshop and 100% became certified LIFE interventionists (33%). Of the 33 individuals who attended a Birmingham recruitment session and feedback group, eight (six African American women; two African American men), participated in the training workshop and 100% became certified LIFE interventionists (24%).

Demographic data were available for the 12 RSVs who participated in additional training sessions. Of these, 10 were women (4 Caucasian, 6 African American) and 2 were African American men. Two reported their health status as “fair”, whereas 10 reported their health status as “good” to “excellent.” On average, volunteers reported 16.75 years of education (SD = 2.45; range 13 to 21 years) and 3.16 years of volunteer experience (SD = 6.00; range 0–15).

Six volunteers actively worked with a family as a LIFE interventionist; the others reported being ill, “too busy” or were awaiting assignment of a family at the close of data collection. Of the six active volunteer interventionists, one worked with three families, two worked with two families and three with one family each. Notably, of volunteers who worked as an interventionist with a family, 100% chose to work with additional families and were awaiting further assignments.

Qualitative Analysis of Feedback Group Interviews Following Recruitment Meetings

Four themes arose from the feedback groups following the four recruitment meetings: (a) questions about the LIFE intervention process; (b) concerns about the patient’s health; (c) positive perceptions of the intervention; and (d) personal experiences leading to suggestions about the characteristics of successful RSV interventionists.

Questions About the LIFE Intervention Process

It included “how do you select these [patients]? Do they come to you from, I guess, from medical resources?” Several potential volunteers expressed concern about the initial meeting with family dyads: “How do you meet the family? I mean, do you just go knock on the door and say, ‘Hi…?’” Concern about home visits also arose regarding allergies to pets and cigarette smoke. A third major focus of RSV questions about LIFE implementation was “how wide does a volunteer have to go?” or concern over geographic distance and following directions.

Concerns About the Patient’s Health

Potential interventionists expressed anxiety related to patients’ stage of illness and the need for matching RSVs with dyads facing illness with which the RSV would feel comfortable. One stated, “So you just need to understand, you know, if we decide to do this, just to make sure that we’re okay and we don’t have any phobias about the condition of the patient.” Another RSV discussed this concern from a practical standpoint, “Sometimes we tend to think of every sick person is contagious or…it’s something I’m gonna get. You can’t catch diabetes. You can’t catch Alzheimer’s dementia.”

Positive Perceptions of the LIFE Intervention

Most potential volunteers reacted positively to the reminiscence and creative activity components of the LIFE intervention. Specifically, RSVs expressed enthusiasm that, within the context of advanced chronic illness, someone was going to talk about life accomplishments rather than sickness. One stated, “It would help the patient not to focus so much on the day-to-day drudgery of caring for the illness. And it would also help the caregiver not to be so . . . problem-focused.” Another mentioned the usefulness of providing structure to such interactions:

It would help the patient to do this in an organized way. Because usually when people are ill and dying, they do wanna talk to you and tell you about the things that are important, but there’s no organization to it. So this would give them a procedure in which to do it that would make it more beneficial and lasting.

Another RSV noted that “I think it will help relieve the stress of the caregiver, because they would be focused on doing something positive that they both would, you know, enjoy doing.” Overall enthusiasm for this volunteer opportunity was expressed by one RSV:

I think most of the volunteers that I know, who I’ve met around here and through my church, would not be intimidated by it; they would see it as an opportunity to help someone else, and something that they could do without intensive training.

Personal Experiences and Suggestions About the Characteristics of Successful RSV Interventionists

The fourth theme that arose from feedback groups dealt with perceptions of the characteristics of a good LIFE interventionist, including good interpersonal skills (e.g., being “a good listener”), empathy, patience, and respect. One RSV stated, “It’d take a certain kind of person that can deal with illness and not become emotional themselves.” RSVs also shared a variety of personal experiences illustrating periods of their own lives when such an opportunity to work with a volunteer on a LIFE project would have been meaningful. Examples included placement of relatives in skilled nursing facilities, health decline of loved ones due to cancer or dementia, and the death of loved ones.

I didn’t know it existed. And I was an in-home caregiver for an Alzheimer patient for like three years...it’d have been good to have somebody, even when he first got sick, to start [a LIFE project]. Maybe it would’ve helped him from being advanced.

Changes made to LIFE to incorporate RSV feedback

In response to feedback from RSVs during recruitment meetings and feedback groups, a protocol was developed to match LIFE community-dwelling dyads with RSV interventionists. Characteristics considered during matching included geographic proximity, RSV comfort with the illness of the palliative care patient, issues of cigarette smoking and pet ownership in patient/caregiver homes, and needs of the dyad in comparison with skills of the RSV (e.g., dyads with more complicated presentation such as a mental health diagnosis were matched with RSVs with prior work experience as an MSW). Additionally, if requested by the RSV, LIFE research staff agreed to meet with RSVs and families at the initial meeting. In the cases in which this procedure was implemented, LIFE research staff made initial introductions and then excused themselves from the session so that the RSVs could begin the intervention with the dyad.

Post-intervention RSV Interventionist Interviews

The major themes and subthemes emerging from individual semi-structured interviews with the six active RSV interventionists are presented in Table 1. Salient themes identified from exit interviews included positive and negative aspects of the experience (e.g., challenges), recommendations for the process of LIFE implementation, reactions to the Interventionist Manual, feelings arising during work with patient/caregiver participants, and personal reflections. Subthemes identified within positive aspects of the experience included value to patient/caregiver participants, motivation of patient/caregiver participants (positive valence), and good experience for the RSV. Regarding value and motivation of patient/caregiver participants, one volunteer stated:

Table 1.

Major Themes and Subthemes Emerged from Semi-structured RSV Post-intervention Interviews

| Major themes | Subthemes | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Positive aspects | (1a) Value to patient/caregiver participants | “I felt like it was something they saw as valuable and that they got involved in. ...As a matter of fact, it affected me, and I’ve gotten involved in doing a little something on my own for my family.” [RSV#3002] “It made her feel important or that she was valuable, that she had something to leave.” [RSV #3104] |

| (1b) Motivation of patient/caregiver participants | “I really enjoyed working with this family ‘cause she was really, really interested. Kinda the sad part was her caregiver, her daughter, was not as interested.” [RSV#3108] “They had been wanting to do something, wanting to do something but had never gotten started, and so this got them started, so I felt good about that.” [RSV#3002] |

|

| (1c) Good experience | “Well, they were close to my age…that made it good for me because, um, it was very easy to relate to, um, the things…I was very pleased, am very pleased with the participants.” [RSV#3105] “It was very rewarding for me because I had never really thought about the importance of the wisdom, you know, that the older potentially have, and this lady…was like 93 years old and so she’s seen a lot in her life, and she was willing to share it.” [RSV#3104] |

|

| (2) Challenges or negative aspects | (2a) Desire for closure (2b) Scheduling (2c) Motivation of caregiver participants |

“I would have liked them to see some closure on the project. … you went three times, and in both cases, some kind of family health issue came up where they had to take time off and everything and they haven’t finished it.” [RSV #3002] “The hardest thing for me was finding time since I work.” [RSV#3004] “We had to set the time up around when her niece could be there from her work.” [RSV#3104] “I would have preferred having a caregiver or something more actively involved in the project.” [RSV#3108] |

| (3)Recommendations for process | (3a) Number of sessions (3b) Follow-up (3c) Time between sessions |

“I think they could have done with four intervention sessions… because they had barely gotten started.” [RSV#3001] “I would just like to know if she…if it still has some meaning for her, more than anything, even if she didn’t continue doing… does she still have good memories of that? Does she still have that book that we started that she could go back to look at.” [RSV#3108] “that might be a suggestion…’You got such a great start, you’ve gone this far and everything, and you indicate you want to go a little bit farther, and I’d like to see it, just to share with you and see you again.” [RSV#3002] “I think you guys said that we should see them once a week, but I think that’s too close. So I was giving the clients two weeks apart.” [RSV#3001] “Oh, well, there were several weeks. And that was because of a holiday and, um, I had to go out of town. And then, um, the participant’s caregiver was out of town. So there were a few weeks that were, you know, it didn’t flow 1-2-3.” [RSV#3105] |

| (3d) Need refresher training | “If there is a period of time between your initial training and when you actually get a family, going over/reviewing things briefly…gives a little reassurance so that if you suddenly decide you have some questions …you can go over those.” [RSV #3002] “The reading material was what was helpful, ‘cause after that, you always just need a little boost, especially if you don’t go ahead and start doin’ a project right away.” [RSV #3108] |

|

| (4) Interventionist manual Structure | “I don’t like to feel and this comes from a lot of experience as a social worker, I don’t like to feel like I have to ask certain questions to get at what’s going on in the room.” [RSV #3004] “Well in my case…to have that notebook to look down at and go through, ‘Okay, we’ve done this step, this step…’ and you know, I’d mark off the things.” [RSV #3002] “It really is laid out when you start talkin’ with them…it helps you kinda get to know them, get an idea of what they want to do and everything, too. So that was laid out real well.” [RSV#3108] |

|

| (5) Reactions to work with patient/caregiver participants | “I love a good story. It makes me feel good because I like swapping yarns with people.” [RSV#3001] “I felt like it brought out positive things for them to have as an interchange, you know, in this stage of their life, and particularly with one of the persons involved not in good health but that they could contribute, too.” [RSV#3002] |

|

| (6) Personal reflections | “So that got me to thinking I should do this with my mother and with my aunts and…you know, because it’s a good thing, because they know things that once they’re gone, it’ll be gone unless we go read the book.” [RSV#3104] “I think that it was helpful to the participants, because as sisters, they had this love for each other…I don’t think they realized how interwoven they were, um, until this…I was just amazed ‘cause I was an only child and I thought, oh, this is just wonderful. I thought it was just wonderful that, you know, how they loved each other and that they could see that.” [RSV#3105] |

It really has a lot of value in making people realize the value of their lives. A lot of people just look back and have regrets….

Another RSV described the value she found in the experience as an interventionist:

It made me have a deeper appreciation for older seniors, and it just made me feel good to know that I was helping somebody else to do something that increased probably their self-esteem. And it didn’t take long, it didn’t cost me money, and it didn’t cost me much time.

Summing up the positive aspects for all involved, one RSV said, “….so, the family is helped, the participant/senior citizen is helped, and the volunteer is ‘helped.’ We all are made to feel like we’re doing something worthwhile.”

RSVs also reported challenges or negative aspects of the LIFE intervention as a volunteer opportunity. Subthemes included desire for closure, scheduling, and motivation of patient/caregiver participants (negative valence). RSVs mentioned a desire to see the final product of the creative activity, as many families had not completed the project by the end of the third and final intervention session. Another challenge expressed was scheduling of sessions with the patient/caregiver participants. Difficulties in scheduling sessions were due to illness of a patient or caregiver, holidays, and other responsibilities of the patient participants, caregivers, and RSVs (e.g., work). The third and final subtheme was motivation, generally of the family caregiver, to engage in the project. Volunteers also expressed some frustration when patient/caregiver participants did not make much progress on their project in between intervention sessions.

The third major theme revolved around the RSVs’ recommendations for LIFE project implementation after having gained experience with at least one family dyad. In response to the above-mentioned desire to see the completed project, RSVs recommended that a fourth session or an additional follow-up session scheduled several months later be part of the LIFE intervention protocol. According to one volunteer, “My only regret was that I didn’t get to see the project all the way through to completion, but I did the three visits and I left them in the middle of it.” Volunteers also recommended a greater length of time between intervention sessions, citing patient/caregiver participants’ need to gather materials and desire to start the work. Other reported barriers included illness, travel, and holidays, making the once-per-week intervention schedule untenable. The fourth recommendation offered by RSVs was to offer refresher or booster training for volunteers when a gap between initial training and assignment of the first family or a new family for intervention occurred.

Regarding perceptions of the Interventionist Manual (see Table 1), RSVs generally believed that it was most useful in providing a structure for their interactions with the patient/caregiver participants. They appropriately used it as a guide for the intervention sessions. One volunteer shared how she used the manual:

Before each meeting and each phone call, I would read it to see the main points of what I was supposed to do, and so that was helpful. It did help me to prepare myself mentally for what I’ve got to accomplish at this meeting.

However, RSVs’ appreciation of the Interventionist Manual depended on their own work experience; one volunteer cited preferring to rely on her skills as a social worker rather than following a structured interaction (see Table 1).

RSVs shared several reactions to their work with patient/caregiver participants. These ranged from neutral reactions such as “you know, isn’t that weird? I don’t have any feeling about that one way or the other because I help people recall memories every day” to positive emotions:

I enjoyed the sessions…I enjoyed getting the ladies motivated to begin compiling their photograph album. … I liked seeing the mother and daughter working together to gather their items and gather their photographs…And I liked being able to find a way to engage the caregiver.

In addition to these areas that related specifically to the intervention itself, RSVs reflected on their interactions with patient/caregiver participants. One volunteer stated:

You know, I still wish my grandmother was here and I could talk to her. So since I can’t, that’s another way that it benefitted me: to talk to an older person. Because when I was younger, I didn’t want to hear it, to be honest with you (laugh). I was like, ‘I don’t wanna hear that old stuff. That was back in the old days.’ But now I appreciate it more.

Much of what made the experience meaningful to volunteers surrounded recalling memories from their own family situations that reinforced the importance of having a concrete remembrance of family legacies (Hunter & Rowles, 2005).

In addition to these major themes and subthemes, several RSVs mentioned that the support received from the LIFE research staff was important in preparation for and implementation of the intervention sessions. Most of all, they reported that just having someone to contact, for any reason, made them comfortable with their role in the project:

I liked being able to have a contact person to call and ask them questions. ... ‘cause even if you had all the training in the world, or even the book, there are some times something’ll come up that you have a question about and you just need to be able to talk to somebody about it.

Discussion

This qualitative evaluation of the RSV experience in translation and implementation of the LIFE intervention extends prior research in several ways. First, this is one of the few evaluations of an evidence-based intervention with theoretical underpinning and using a strength-based approach to utilize readily available RSVs as intervention agents for at-risk community-based populations (e.g., palliative care patients and their family caregivers). Second, a CBPR framework was used throughout to involve stakeholders in senior centers and solicit input from volunteers during recruitment, training, and after implementation of the project with families. Third, skill in RSVs’ treatment delivery and their perceptions of the usefulness of the Interventionist Manual were directly assessed. Fourth, it is noteworthy that the intervention effects achieved by RSVs working with individuals with advanced chronic illness and their family caregivers (Allen et al., 2014) were comparable to those achieved in the initial efficacy trial with professional interventionists (Allen et al., 2008). Finally, the themes identified by RSVs participating as LIFE interventionists reveal potential characteristics needed to be successful and mechanisms associated with positive short-term outcomes for the RSV that could result in long-term health benefits such as reduced risk of dementia (Anderson et al., 2014).

One of the challenges to provision of mental health services and wellness or strengths-based interventions in the community is the disparity between need and the number and costs of professional service providers available to meet that need (Kazdin & Blase, 2011). Chronic advanced illness is associated with negative mental health outcomes including stress and depression (Solano, 2006). The prevalence of angina/coronary heart disease, arthritis, cancer, diabetes, heart attack, hypertension, and stroke increase across the lifespan (Pearson et al., 2012), and older adults represent the fastest-growing segment of the U.S. population. According to Bodenheimer and colleagues (2002), problems in the implementation of the current primary care system in the United States limit the ability to meet the needs of individuals with advanced chronic illness and their family caregivers. Therefore, it is possible that RSVs working within senior centers may be an available, interested, and talented resource to meet the needs of at-risk community-dwelling older adults and their families. RSVs could be a low-cost alternative to mental health professionals for delivery of highly structured and simple evidence-based interventions given the necessary training. The current project evaluation and the results of the randomized controlled effectiveness trial (Allen et al., 2014) support this contention. Moreover, a recent review suggests that volunteerism may have long-term preventive health implications for volunteers in addition to proximal benefits for psychosocial, physical, and cognitive functioning (Anderson et al., 2014).

Implications for Translation and Challenges

Important data for consideration of this training program prior to widespread adoption is the relative cost of engaging senior centers or other community organizations for older adults in the recruitment and training process. A similar point regards the relative number of trained RSV interventionists (12) to those who attended initial meetings (45) in this project. The low recruitment rate illustrates a challenge for further translation of the intervention. Potential means of addressing this low recruitment rate would be to provide testimonials from prior LIFE RSV interventionists about their experience or evidence that engagement as a volunteer interventionist has long-term preventive health benefits. It is possible that the experiences shared by active interventionists were positively skewed due to self-selection of RSVs who were positively disposed to becoming a LIFE interventionist at the time of the initial recruitment and feedback session. Volunteerism, however, is predicated on choosing experiences that are personally meaningful, including the choice to volunteer with at-risk populations (Hiatt & Jones, 2000). Therefore, in general, it is likely that volunteers will be positively disposed to the volunteer activities in which they choose to engage.

Another consideration was relatively low retention from training to implementation of the LIFE intervention with families. One reason for this in the current study was the slow rate of referral of palliative care dyads to the project, which caused some interventionists to wait long periods before receiving a first referral. Potential solutions would be (a) partnering with medical homes or large geriatric primary care centers or (b) greater community outreach and working with faith-based organizations to identify appropriate patient-caregiver dyads. Although project logistics were the primary reason that not all trained RSVs were immediately paired with a patient/caregiver dyad, other self-selection issues could be at play. For example, comfort and familiarity with home-based programs may have been a factor as two of the volunteers who worked with patient/caregiver dyads reported their primary occupation as “licensed social worker.” Notably, however, no data were collected to directly inform future translational efforts as to characteristics that differentiated active volunteers from trained RSVs that did not implement the intervention. All volunteers who had engaged in LIFE implementation with families expressed desire to work with additional families and seemed to possess all the characteristics necessary for a “good” interventionist mentioned within feedback groups. Also, RSVs proved to be very conscientious about being prepared for their role in working with older adults with advanced chronic illness and their family caregivers.

As with any research this project has limitations. First, implementation was restricted to one geographic area in the Southeast. Generalizability of findings to other areas is unknown. Second, the number of senior centers (2), feedback groups (4), and RSV interventionists with LIFE implementation experience (6) is small. Replication is needed to build on these initially promising results. Third, a larger trial would offer the possibility of consenting larger numbers of volunteers and including quantitative as well as qualitative evaluations of characteristics associated with success. One interesting characteristic for future exploration is the psychological flexibility demonstrated by successful RSVs.

Despite these limitations, current results suggest that older volunteers can successfully implement a reminiscence and creative activity intervention, provide recommendations for improving its implementation, and receive personal benefit from their involvement. Agencies serving older adults and their families may benefit through such structured programs to provide meaningful volunteer opportunities and meet community needs. With regard to policy and societal impact, current and future policy efforts geared toward increasing volunteerism depend on (a) volunteer organizations’ uptake of preventive and therapeutic interventions for their communities, and (b) the effectiveness of volunteers to meet unmet service needs among at-risk populations. Further evaluation data are necessary to examine the costs and benefits of incorporating RSV-focused training programs into the response for mental health and wellness needs of community-based older adults and their families.

Funding

This project was supported by funding from the National Institute of Nursing Research (R21NR011112 to R.S.A.).

Acknowledgments

A Special thanks to Drs. Regina Harrell, Richard Sims, Ali Ahmed, Andrew Duxbury, Kelli Flood, and to Ms. Mary Hardrick and Ms. Starr P. Culpepper for assistance in recruitment and to Dr. Michelle M. Hilgeman and Leslie A. Miller, MSW for assistance in initial volunteer training. Most especially, the LIFE team extends its thanks to the staff and RSV participants of FOCUS on Senior Citizens and Positive Maturity for supporting volunteer recruitment and involvement, and to all of the patients and caregivers who gave generously their time and energy to this project.

References

- Allen R. S. Hilgeman M. M. Ege M. A. Shuster J. L., & Burgio L. D (2008). Legacy activities as interventions approaching the end of life. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 11, 1029–1038. doi:10.1089/jpm.2007.0294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen R. S. Harris G. M. Burgio L. D. Azuero C. B. Miller L. A. Shin H., …Parmelee P (2014). Can senior volunteers deliver reminiscence and creative activity interventions? Results of the Legacy Intervention Family Enactment (LIFE) randomized controlled trial. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 48, 590–601. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson N. D. Damianakis T. Krӧger E. Wagner L. M. Dawson D. R. Binns M. A., …Cook S. L; for the BRAVO Team. (2014). The benefits associated with volunteering among seniors: A critical review and recommendations for future research. Psychological Bulletin, 140, 1505–1533. doi:10.1037/a0037610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T. Wagner E. H., & Grumbach K (2002). Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: The chronic care model, Part 2. JAMA, 288, 1909–1914. doi:10.1001/jama.288.15.1909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley E. H. Curry L. A., & Kelley J. D (2007). Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Services Research, 42, 1758–1772. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen L. L. Isaacowitz D. M., & Charles S. T (1999). Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist, 54, 165–181. doi:10.1037//0003-066X.54.3.165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chochinov H. M. Kristjanson L. J. Breitbart W. McClement S. Hack T. F. Hassard T., & Harlos M (2011). Effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncololgy, 12, 753–762. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70153-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chochinov H. (2012). Dignity therapy: Final words for final days. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Corporation for National and Community Service. (2012). Research brief: Volunteering in America research highlights Retrieved November 10, 2014, from http://www.nationalservice.gov/impact-our-nation/research-and-reports/volunteering-america

- D’Zurilla T., & Nezu A (2007). Problem-solving therapy: A positive approach to clinical intervention (3rd ed.). New York: Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S. (1997). Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Social Science and Medicine, 45, 1207–1221. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00040-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A. H. S, & Thoresen C. E (2005). Volunteering is associated with delayed mortality in older people: analysis of the longitudinal study of aging. Journal of Health Psychology, 10, 739–752. doi:10.1177/1359105305057310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiatt S. W., & Jones A. A (2000). Volunteer services for vulnerable families and at-risk elderly. Child Abuse and Neglect, 24, 141–148. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(99)00112-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter B. G., & Rowles G. D (2005). Leaving a legacy: Toward a typology. Journal of Aging Studies, 19, 327–347. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2004.08.002 [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin A. E., & Blasé S. L (2011). Rebooting psychotherapy research and practice to reduce the burden of mental Illness. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 21–37. doi:10.1177/1745691610393527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez I. L. Frick K. Glass T. A. Carlson M. Tanner E. Ricks M., & Fried L. P (2006). Engaging older adults in high impact volunteering that enhances health: recruitment and retention in The Experience Corps Baltimore. Journalof Urban Health, 83, 941–953. doi:10.1007/s11524-006-9058-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow-Howell N. Hong S., & Tang F (2009). Who benefits from volunteering?: Variations in perceived benefits. The Gerontologist, 49, 91–102. doi:10.1093/geront/gnp007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okun M. A., & Schultz A (2003). Age and motives for volunteering: Testing hypotheses derived from socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychology and Aging, 18, 231–239. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omoto A. M. Snyder M., & Martino S. C (2000). Volunteerism and the life course: Investigating age-related agendas for action. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 22, 181–197. doi:10.1207/S15324834BASP2203_6 [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L. I. Mullan J. T. Semple S. J., & Skaff M. M (1990). Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist, 30, 583–594. doi:10.1093/geront/30.5.583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson W. S. Bhat-Schelbert K., & Probst J. C (2012). Multiple chronic conditions and the aging of America. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health, 3, 51–56. doi:10.1177/2150131911414577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. (2000). Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health, 23, 334–340. doi:10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4<334::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solano J. P. Gomes B., & Higginson I. J (2006). A comparison of symptom prevalence in far advanced cancer, AIDS, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and renal disease. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 31, 58–69. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe R., & Holt R.(Eds.). (2007). The Sage dictionary of qualitative management research. London, England: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Zedlewski S. R., & Schaner S. G (2006). Older adults engaged as volunteers. The retirement project: Perspectives on productive aging. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]