Abstract

The aim of the present study was to investigate the computed tomography (CT) manifestations of Wegener granulomatosis (WG) in the chest and potential reasons for misdiagnosis. Conventional CT scans and clinical data of 45 patients with WG were retrospectively analyzed. Patients typically presented with multiple system involvement, primarily in the upper and lower respiratory tract. The incidence of thoracic involvement was 75.56% (34/45). Radiographic features were varied between cases in the present study, with the most common features being numerous cavitary nodules and masses in the lungs. Cavitations were usually irregular, with uneven wall thickness, partial centrality, fuzzy inner edges and piecemeal necrosis. These results indicate that WG typically has multiple system involvement, with the chest being most prominent. Multiple variable-sized cavitary nodules with irregular edges and piecemeal necrosis were the most notable features revealed using CT scanning; however, in order to give a definitive diagnosis, biopsies should be performed.

Keywords: Wagener's granulomatosis, tomography, X-ray computed, diagnostic errors

Introduction

Wegener's granulomatosis (WG) was first described by German pathologist Dr Friedrich Wegener as rhinogenic granulomatosis in 1936 (1) and is an uncommon vasculitis of small and medium-sized arteries (2). WG, which is an angiogenic and multiple system necrotizing disease involving the upper and lower respiratory tract and kidneys (3–6), is affected by a number of factors, including heredity, infection, the immune system and the environment, and diagnosis is typically confirmed via clinic and laboratory examinations (7). Exposure to environmental agents, including cadmium (8), silica, mercury, sand dust and volatile hydrocarbons, has been reported to lead to the development of WG; however, no single causative agent has been identified (9). Modern immunosuppressive treatment methods greatly improve patient outcomes, with the estimated median survival time increasing to 21.7 years post-diagnosis (10). Patients may develop WG at any age, with the mean age at diagnosis being 50 year, and males and females are equally affected (11). The majority (~90%) of clinically apparent cases are reported in Caucasian individuals (11).

The thorax is commonly involved in WG and, as such, the majority of patients present with pulmonary or upper respiratory tract involvement (12). Due to its high sensitivity for detecting pulmonary involvement, computed tomography (CT) is primarily used to examine the chest in patients with WG (13–15). However, since certain characteristics of WG are difficult to detect using clinical, laboratory and imaging examination it is frequently misdiagnosed.

In the present study, the clinical manifestations, CT results and diagnosis of 45 patients with diagnosed WG were retrospectively reviewed. The aim of the present study was to identify ways of decreasing the rate of misdiagnosis and improving the diagnostic accuracy of WG involving the chest with CT.

Materials and methods

Patients

A total of 45 patients with clinically confirmed WG were selected retrospectively using a computerized search of records from patients who were treated at the Chinese PLA General Hospital (Beijing, China) between January 2011 and June 2013. The patients, including 24 men and 21 women, were 19–74 years old (mean, 46±12.2 years). The clinical symptoms were as follows: Fever accompanied with or without fatigue (n=26, 26/45; 57.78%), night sweats (n=2, 2/45; 4.44%), weakness (n=2, 2/45; 4.44%), abnormal myelogram (n=29, 29/45; 64.44%), cough (n=25, 25/45; 55.56%) and expectoration (n=15, 15/45; 33.33%). A total of 32 patients underwent screening examination with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) and a total of 28 patients received biopsy, including a CT-guided percutaneous transthoracic lung biopsy (n=10), transbronchoscopic biopy (n=1), paranasal sinuses and nasal biopsy (n=14), percutanenous renal biopsy (n=1), parotid gland biopy (n=1) and skin biopsy (n=1). The other 17 patients were diagnosed based on the 1990 American College of Rheumatology criteria (Table I) (9), when a minimum of 2 items in Table I were met. All patients received glucocorticosteroid therapy (predisone) at a dosage of 1.0 mg/kg per day for 4 weeks and then low dose maintenance. Following treatment, the symptoms of all patients was relieved to varying degrees. Written consent was obtained from all participants and the present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hainan Branch of the Chinese PLA General Hospital (Hainan, China).

Table I.

American college of rheumatology diagnostic criteria for Wegener granulomatosis.

| Criteria | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Nasal or oral inflammation | Painful or painless oral ulcers, purulent or bloody nasal discharge |

| Abnormal chest radiograph | Nodules, fixed infiltrates, cavities |

| Urinary sediment | Microhematuria (>5 red blood cells per high-power field), red cell casts |

| Granulomatous inflammation at biopsy | Involvement of the wall of an artery/arteriole, involvement of the perivascular/extra vascular space |

The presence of two or more of the four criteria is associated with a sensitivity of 88.2% and a specificity of 92% for Wegener granulomatosis.

CT technique

In the present study, 43 patients underwent CT scanning. CT results were not available for the other 2 patients as they were transferred to a different hospital. CT scans were performed using a Siemens Sensation Cardiac 64 detector-row CT scanner (Siemens AG, Munich, Germany). The scan parameters were the same for each patient: Tube current, 900 mA; tube voltage, 120 kV; slice thickness, 5.0 mm; matrix, 512×512. The raw data were reconstructed using 5 mm thickness standard algorithms combined with a 2 mm thickness high-resolution construction in the region of interest. The images were mainly reviewed at the lung window setting with an about 1600 HU of window width and a 600 HU of window level. All the CT images were simultaneously reviewed by two independent and experienced chest radiologists who were blinded to the study conditions.

Results

Involved location of WG patients

System involvement varied between the 45 patients assessed in the present study and included thoracic involvement (n=34), renal involvement (n=10), skin involvement (n=7), larger joint involvement (n=14) and parotid gland involvement (n=1; data not shown). A total of 6 patients presented with the classic clinic triad (upper respiratory tract, lung and renal involvement).

Results of laboratory pathology investigation

Of the 32 patients who underwent ANCA screening examination (Table II), 27 (84.38%) were ANCA-positive, which included cytoplasmic ANCA (n=20) and perinuclear ANCA (n=7). Among the 28 patients who underwent biopsy, 27 patients received a confirmed diagnosis (96.43%).

Table II.

Clinical and CT manifestations of 45 patients with Wegener granulomatosis.

| Item | Value (%) |

|---|---|

| General information | |

| Male | 24 (53.33) |

| Female | 21 (46.67) |

| Age (years) | 46.4±12.2 |

| Clinical manifestation | |

| Fever, combined ear/eye/mouth and nasal symptoms | 22 (48.89) |

| Fever, chest tightness, cough/cough blood | 6 (13.33) |

| Cough/cough sputum, ear/eye/mouth and nose symptoms, no fever | 13 (28.89) |

| Cough/cough/blood, no fever | 4 (8.89) |

| Laboratory examination | |

| Positive ANCA | 27 |

| Negative ANCA | 1 |

| Thoracic CT findingsa | |

| Nodules: Solid, ground glass opacity, cavity nodules | 11 (25.58) |

| Patchy shadows: Ground glass opacity, consolidation, combined cavity | 5 (11.63) |

| Lump, combined cavity | 1 (2.33) |

| Nodules combined with patch and/or lump | 12 (27.91) |

| Intrapulmonary lesion combined with large airway involvement: diffused tube wall thickening or intratracheal soft tissue | 2 (4.65) |

| Large airway involvement: Localized thickening of tracheal wall | 1 (2.33) |

| Intrapulmonary lesion combined with pulmonary artery: Tube wall thickening combined with embolism | 2 (4.65) |

| Normal thoracic CT findings | 9 (20.93) |

2 patients did not undergo CT scan. ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; CT, computed tomography.

Thoracic CT manifestations

A total of 34 patients presented with abnormal pulmonary CT findings (Table II), including large airway involvement (n=1; 2.94%), abnormal lung findings (n=31; 91.18%) and combined large airway and lung involvement (n=2; 5.88%). Bilateral lung abnormalities were observed in 20 patients (58.82%), unilateral lung abnormalities in 13 patients (13/34, 38.24%), pleural alterations combined with effusion in 4 patients (11.76%) and pulmonary artery involvement in 2 patients (5.88%).

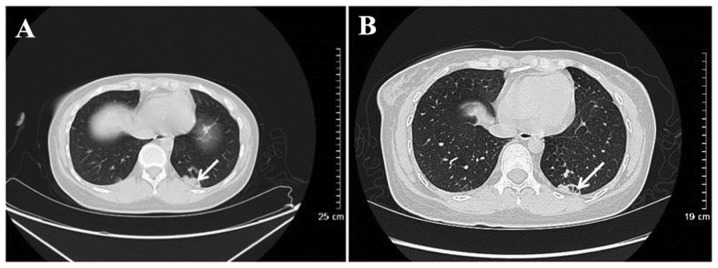

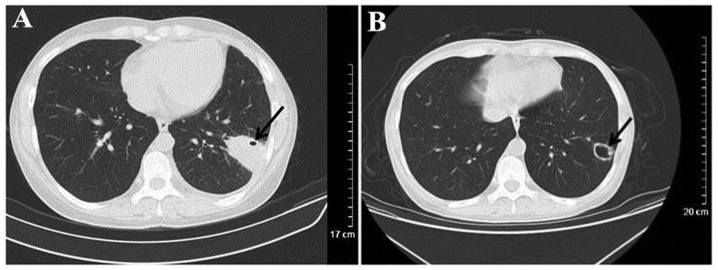

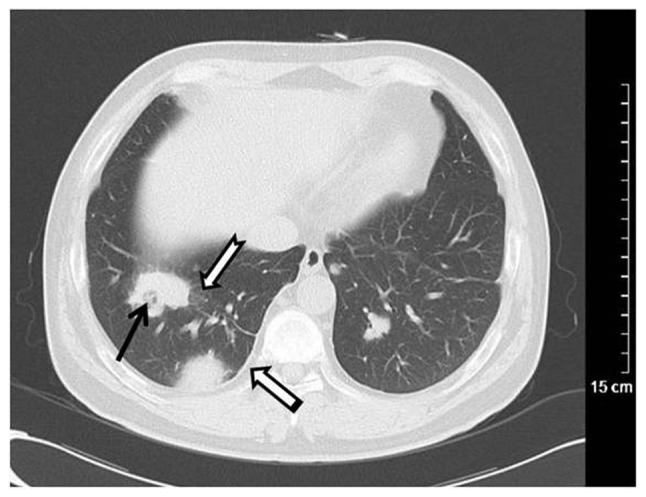

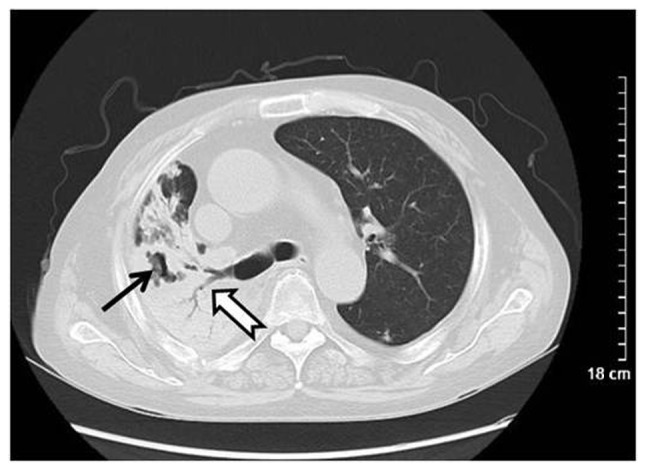

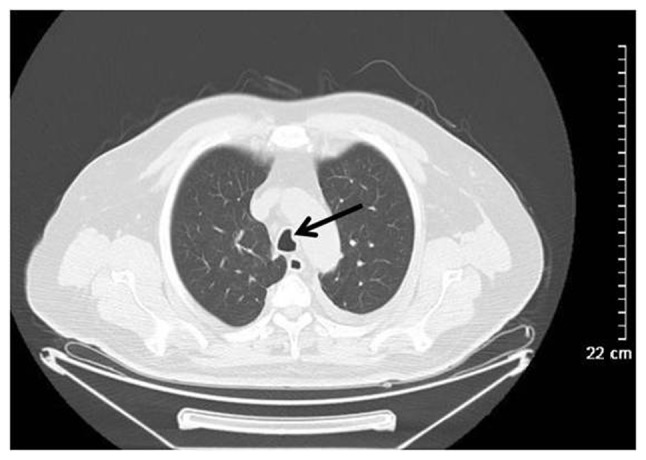

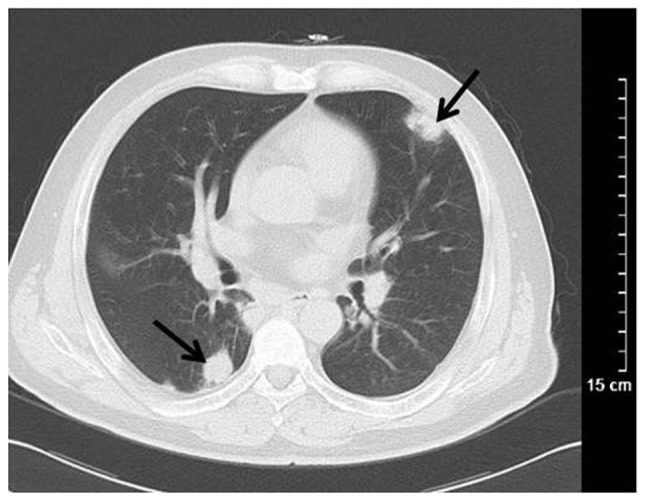

The most common finding was pulmonary nodules ranging in size from 0.3–3.0 cm, which were detected in 25 patients (73.53%; Fig. 1), including unilateral pulmonary nodules (n=7), solitary nodule (n=3), ground-glass nodules (n=2) and nodules combined with halo sign (n=4). CT results for 14 patients revealed cavitary nodules and 5 patients presented with irregular cavity walls combined with necrotic debris (Fig. 2). Nodules combined with lobulation, speculation and vacuoles were observed in 5 patients and 1 patient presented with signs of vessel convergence. Additionally, 15 patients exhibited plaques (44.12%) with ground glass opacity (n=6), pulmonary consolidation (n=6) and cavitation (n=3; Fig. 3). Masses (≥3 cm) were observed in 6 patients (17.65%) and were combined with cavitations in 4 patients, had fuzzy limits and irregular shape in 6 patients, and spiculation in 3 patients (Fig. 1). Bilateral pulmonary interstitial alterations were observed in 1 patient (Fig. 4).

Figure 1.

Wegener's granulomatosis in a 58-year-old female. Computed tomography scanning revealed multiple nodules and irregular masses in bilateral lungs, necrotizing cavities in the local lesions (black arrow), ground glass opacity in the outline of the lesion (dovetail arrow) and pleural thickening adjacent to the lesion (white arrow).

Figure 2.

Wegener's granulomatosis in a 51-year-old female. Computed tomography scanning revealed (A) irregular nodules and cavitations in the left inferior lobar basal segment. (B) Following hormone treatment for 1 month (black arrow) the local lesion was reduced, necrotizing cavitations were larger and piecemeal necrosis was observed in cavitations (black arrow).

Figure 3.

Wegener's granulomatosis in a 67-year-old male. Computed tomography scanning revealed lobar consolidation and irregular necrosis (arrows) in a large area of right lung.

Figure 4.

Wegener's granulomatosis in a 47-year-old female. Computed tomography scanning revealed diffuse small nodules with a centrilobular distribution (white arrow).

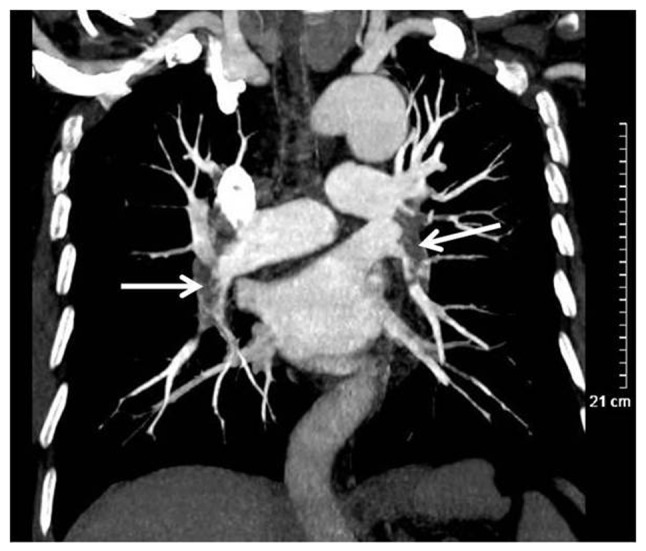

Of the 34 patients who had abnormal pulmonary CT findings, severe airway alterations were observed in 3 (8.82%). This includes 1 patient with changes in the vocal cord and subglottic region, 1 with intratracheal soft tissue shadow and another with bronchial wall thickening (Fig. 5). A total of 2 patients with pulmonary artery involvement were demonstrated to have undergone pulmonary artery alteration, including pulmonary artery wall thickening, which may lead to pulmonary artery embolism (Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

Wegener's granulomatosis in a 49-year-old woman. Computed tomography scanning revealed punctiform soft tissue density nodules in the main trachea (black arrow).

Figure 6.

Wegener's granulomatosis in a 71-year-old male. Computed tomography scanning revealed a marked filling defect in bilateral pulmonary artery (white arrow).

Misdiagnosis based on CT findings

Of the 34 patients with clinically confirmed WG, 12 were diagnosed using CT results (35.29%), 4 patients had inconclusive diagnoses (11.79%), and 18 patients were misdiagnosed (52.94%). Patient misdiagnoses were as follows: 12 were diagnosed with inflammation, including opportunistic infections in 1 patient, mixed infection in 1 patient, interstitial pneumonia in 1 patient, pneumonia with lymphocytic infiltrate in1 patient, fungal infections in 5 patients and viral infection in 3 patients. The CT images obtained for patients who were misdiagnosed with inflammation featured ground glass opacity in 3 patients, patchy shadows in 8 patients, military nodules in 2 patients, pulmonary interstitial alterations in 1 patient, masses in 2 patients and pleural effusion in 2 patients. A total of 6 patients were misdiagnosed with tumors, including combined airway abnormality in 2 patients (airway thickening in 1 patient) and pulmonary interstitial alterations combined with fungal pneumonia in 1 patient.

In WG with lung involvement there may be various imaging manifestations. The atypical CT findings of WG were typically misdiagnosed as infectious lesions or neoplastic lesions. The irregular cavities were typically observed in patients with WG (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Computed tomography scanning of a patient with WG misdiagnosed as infectious lesions. (A) Irregular consolidation in the substrate out of left lower lung, and punctiform vesicle in the consolidation (black arrow). (B) At 3 months post predisone treatment, the lesion markedly reduced in size and evolved into a cavity with a thin-wall (black arrow).

CT imaging of pulmonary abscesses usually reveals thick-walled cavitations based on a high consolidation with the appearance of liquid-gas level in the cavity, which differs from WG. Fungal infections vary widely; floating bacteria may be observed in the void, which is not normally present in WG (16). WG may be misdiagnosed as primary pulmonary or pulmonary metastatic tumors with single and multiple solid mass or nodules (17). When WG appears as a single solid mass, it is not easily distinguished from other lung tumors using CT alone. There are certain differences between WG and pulmonary metastasis in CT findings of multiple nodules (18). It was observed in the present study that the multiple lung nodules of WG are typically shown as variable irregular shapes and the shadow connected to the lesion (Fig. 8). However, multiple pulmonary metastases are generally located in the peripheral region of the lung, with a variable size and smooth boundaries.

Figure 8.

Computed tomography scanning of Wegener's granulomatosis misdiagnosed as tumor-like lesion. Nodules with irregular shapes were dispersed in the lung (black arrows).

Discussion

WG is a rare and angiogenic necrotizing vasculitis, involving the upper and lower respiratory tract, kidney and skin (19). The sex distribution (male:female) of WG is 3:2 and the peak incidence occurs in patients aged between 50 and 60 years (20). The incidence of WG has been increasing annually, which may be a result of increased environmental factors including cadmium, silica, mercury, sand dust and volatile hydrocarbons (9). WG may be a type of inflammation resulting from a hypersensitive response to external antigens (21). Trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole has been previously used to successfully control the progression and relapse of WG (22).

Any part of the body may be involved in WG and the majority of patients present with classic clinic triad of the upper respiratory tract, lung and renal involvement (23). While the number of patients with renal involvement was low in the present study, the ratio of occurrence was lower in those who presented with the classic clinic triad. With the progression of the disease, 80–90% of patients with WG generally present with renal involvement (24). The clinical manifestations of WG are varied, a number of patients with WG present with long-term nasal congestion, which is often misdiagnosed as chronic sinusitis (25,26). Furthermore, some patients present with acute renal and respiratory failure (27,28). Patients with WG with thoracic involvement were typically present with cough, dyspnea, fever and chest pain (29).

WG has been reported to be a type of angiitis associated with ANCA, in particular cytoplasm ANCA (c-ANCA) (30). It was reported that the serum c-ANCA levels during the active phase of WG are elevated in 90% of patients (31). In the present study, 84.38% patients were ANCA-positive and 74.07% patients were positive for elevated c-ANCA levels (20/27); However other diseases, including polyarteritis nodosa, systemic lupus erythematosus, anaphylactoid purpura and Kawasaki disease may also present as c-ANCA-positive (9). Hence, biopsy is the gold standard in the diagnosis of WG (32).

As the majority of WG patients present with upper respiratory tract involvement and 90% of patients exhibit lung involvement (33), CT scans are essential for the diagnosis of WG. Multiple pulmonary nodules and masses are the most common manifestation of pulmonary involvement, the incidence rate of which was 40–70% in the present study. The rate of pulmonary masses was 17.65% (6/34) and the rate of nodules was 73.53% (25/34). Nodules were usually bilateral, numerous and scattered, ranging from 2–4 cm (15,34,35). The nodules in pulmonary involvement were similar, with signs of pulmonary tuberculosis, allergic reaction and acute bacterial, viral and fungal pneumonia with centrilobular distribution. The incidence of cavitation was 25% among patients with nodules >2 cm (15,35). The walls of cavitations, which were eccentric or nodular, had varying thickness and were smooth or irregular. In the present study, the chest CT images revealed cavitation lesions with piecemeal necrosis in certain patients. Cavitations are susceptible to infection, leading to an increase in air-fluid levels, which is easily misdiagnosed as metastatic tumor, pulmonary abscess or septic pulmonary embolism (17). However, flocculent piecemeal fragment in the cavity of metastatic cavity and pulmonary abscess is rare, which may be a useful CT sign for the differential diagnosis between metastatic cavity and pulmonary abscess. Hemorrhage surrounding the nodules manifested as a halo signal on CT images, which was visible at traumatic hemorrhage or alveolar exudation, including bronchioloalveolar carcinoma and abundant vascularity metastasis. In the present study, nodules with cavitation were observed in 14 patients, as indicated by increased air-fluid levels and uneven thickness of cavity walls. A total of 5 patients with nodules with cavitation were misdiagnosed, with a rate of 35.71%; 4 patients were misdiagnosed with infection, and 1 was misdiagnosed with a tumor. Nodules with halo signals were observed in 4 patients. The lung parenchyma of patients with WG in the active stage with hemorrhage resulted in ground glass density and consolidation, which was misdiagnosed as pneumonia. The involvement of pulmonary arterioles in WG patents presented as mosaic perfusion and tree-in-bud (36). Ground glass density in the lungs of patents with WG may occur secondary to hemorrhages, exudation and mosaic perfusion of pulmonary alveoli in small vessel vasculitis (37). Pulmonary consolidation of patients with WG may be caused by pulmonary infarction or pulmonary infection due to small vessel vasculitis (38), which is similar to bacterial, viral and fungal pneumonia, pulmonary tuberculosis, pulmonary edema, acute respiratory distress syndrome or bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (39). A total of 15 patients presented with ground glass opacity and consolidation; 6 among them were misdiagnosed with different types of infection including opportunistic infection in one patient, lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia in another, tumor in 1 patient and fungal infection in 3 patients. Airway involvement has been identified as a late complication of WG, the incidence rate of which has been reported to be 15–25% (40). Airway involvement in WG has been misdiagnosed as tracheo-bronchial tumor and amyloidosis (39). The involvement of the heart and large vessels are rare manifestations of thoracic involvement in WG; 2 patients in the present study presented with damage to pulmonary arteries, which may be caused by the spread of granuloma. However, due to the incomplete information, there is a lack of sufficient evidence to support this point of view.

WG is frequently misdiagnosed as tumor-like lesions, including metastatic tumors and bronchial lung cancer. WG presenting with multiple solid nodules has been misdiagnosed as metastatic tumor; however, CT scans differ from those of patients with metastatic tumors (41). Multiple solid nodules of metastatic tumors are always variable in size and are mainly distributed in the peripheral lung, whereas multiple solid nodules of WG typically present with irregular outlines combined with smooth edges, as well as irregular nodules. CT scans of single nodules or masses in WG are also different in appearance to scans from patients with bronchial lung cancer (42). Additionally, the clinical manifestation and typical laboratory results for WG differ from tumor-like lesions (41). Hence, CT scans combined with clinical and laboratory analysis may reduce the rate of misdiagnosis.

Thorax involvement in WG is common and the CT manifestations are varied. The present study had several limitations, including the relatively small sample size. To improve the accuracy of the diagnosis of WG, it is necessary to perform a large number of case studies. Another shortcoming of the present study was the inconsistent diagnostic criteria. Of the 45 patients, only 28 cases were confirmed histologically, the other 17 cases were diagnosed clinically based on the American College of Rheumatology diagnostic criteria for Wegener granulomatosis. Additionally, another disadvantage was that the present study was retrospective and selection bias may affect the results.

In summary, WG is a rare disease with unknown etiology and complex clinical manifestation. Furthermore, due to difficulties with diagnosis and unfavorable prognosis, early diagnosis of WG is important to manage the symptoms of WG, prevent recurrence and improve the survival rate of patients. Chest CT scans may be used as a basis for the primary diagnosis of WG. The CT manifestation of pulmonary involvement in WG was multitudinous, including multiple pulmonary nodules, ground glass opacity and consolidation, which were misdiagnosed as pneumonia, tumor and other diseases. The results of the present study suggest that multiple nodules and cavitations, irregular cavity walls and piecemeal necrosis in cavitations may be regarded as signs exclusive to WG. Hence, patients with the multiple solid nodules, ground glass opacity and consolidation may be diagnosed with WG. The exclusive signs combined with clinical and laboratory analysis, particularly negative ANCA, may be used as a basis for the diagnosis of WG. CT scans combined with clinical and laboratory analysis and biopsy may be required for the definite diagnosis.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

JKL designed the study, CGL performed the experiments and JJL analysed the data.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written consent was obtained from all participants and the present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Chinese PLA General Hospital (Hainan, China).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Wegener F. Über eine eigenartige rhinogene Granulomatose mit besonderer Beteiligung des Arterien systems und der Nieren. Beiträge Zur Pathologie. 1976;158:127–143. doi: 10.1016/S0005-8165(76)80082-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orden AO, Muñoz SA, Basta MC, Allievi A. Clinical features and outcomes of 37 Argentinean patients with severe granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener Granulomatosis) J Clin Rheumatol. 2013;19:62–66. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e31828632a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bişkin S, Yazici ZM, Kayhan FT, Erdur Ö. Wegener Granülomatoziste KBB Tutulumu. KBB ve BBC Dergisi. 2009;17:62–65. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossini BA, Bogaz EA, Yonamine FK, Testa JR, Penido Nde O. Refractory otitis media as the first manifestation of Wegener's granulomatosis. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;76:541–541. doi: 10.1590/S1808-86942010000400024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scalcon MRR, Pereira IA, Filho AR, Paiva EDS. Manifestação otológica localizada em paciente com granulomatose de Wegener Localized otologic manifestation in a patient with Wegener's granulomatosis. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2008;48:253–255. doi: 10.1590/S0482-50042008000400011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fonseca FP, Benites BM, Ferrari ALV, Sachetto Z, de Campos GV, de Almeida OP, Fregnani ER. Gingival granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener's granulomatosis) as a primary manifestation of the disease. Aust Dent J. 2017;62:102–106. doi: 10.1111/adj.12441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bîrluţiu V, Rezi EC, Bîrluţiu RM, Zaharie IS. A rare association of chronic lymphocytic leukemia with c-ANCA-positive Wegener's granulomatosis: A case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:145. doi: 10.1186/s12957-016-0901-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gambini G, Leurini D. Cadmium exposure and Wegener's granulomatosis: Case report. Med Lav. 1992;83:349–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez F, Chung JH, Digumarthy SR, Kanne JP, Abbott GF, Shepard JA, Mark EJ, Sharma A. Common and uncommon manifestations of Wegener granulomatosis at chest CT: Radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2012;32:51–69. doi: 10.1148/rg.321115060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wojciechowska J, Krajewski W, Krajewski P, Kręcicki T. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis in otolaryngologist practice: A review of current knowledge. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;9:8–13. doi: 10.21053/ceo.2016.9.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olivencia-Simmons I. Wegener's granulomatosis: Symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2007;19:315–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2007.00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eustaquio ME, Chan KH, Deterding RR, Hollister RJ. Multilevel airway involvement in children with Wegener's granulomatosis: Clinical course and the utility of a multidisciplinary approach. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;137:480–485. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2011.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jbara MH, Vanlandingham A, Tawadros F, Moorman J. Appalachian Student Research Forum. D.P. Culp Centre at ETSU; Johnson City, TN, USA: Apr 6–7, 2016. Cavitary lung lesion with pulmonary embolism: Case of active granulomatosis with polyangitis (Wegener's Granulomatosis). Poster Presentation, no.174. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xia LL, Radiology DO, Hospital XR. Clinical evaluation onthe diagnostic value of multi-slice CT in the diagnosis of pulmonary Wegener's granulomatosis. Qiqihar Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2015;31:19. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guneyli S, Ceylan N, Bayraktaroglu S, Gucenmez S, Aksu K, Kocacelebi K, Acar T, Savas R, Alper H. Imaging findings of pulmonary granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener's granulomatosis): Lesions invading the pulmonary fissure, pleura or diaphragm mimicking malignancy. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2016;128:809–815. doi: 10.1007/s00508-015-0747-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bülbül Y, Ozlü T, Oztuna F. Wegener's granulomatosis with parotid gland involvement and pneumothorax. Med Princ Pract. 2003;12:133–137. doi: 10.1159/000069111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang XL, Tan RS, Liu X. The CT manifestations analysis of pulmonary Wegener's granulomatosis with literature review. JPMI. 2015;16:494–497. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weir IH, Müller NL, Chiles C, Godwin JD, Lee SH, Kullnig P. Wegener's granulomatosis: Findings from computed tomography of the chest in 10 patients. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1992;43:31–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanisch M, Fröhlich LF, Kleinheinz J. Gingival hyperplasia as first sign of recurrence of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener's granulomatosis): Case report and review of the literature. BMC Oral Health. 2016;17:33. doi: 10.1186/s12903-016-0262-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wallace ZS, Lu N, Miloslavsky E, Unizony S, Stone JH, Choi HK. Nationwide trends in hospitalizations and in-hospital mortality of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener's) Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2017;69:915–92. doi: 10.1002/acr.22976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerhild TL, PMID, Wegener Wegener'S Granulomatosis. Polic. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kronbichler A, Jayne DR, Mayer G. Frequency, risk factors and prophylaxis of infection in ANCA-associated vasculitis. Eur J Clin Invest. 2015;45:346–368. doi: 10.1111/eci.12410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White ES, Lynch JP. Pharmacological therapy for Wegener's granulomatosis. Drugs. 2006;66:1209–1228. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200666090-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Y, Ding Y, Liu Z, Zhang H, Liu Z, Hu W. Long-term outcomes in antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-positive eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis patients with renal involvement: A retrospective study of 14 Chinese patients. BMC Nephrol. 2016;17:101. doi: 10.1186/s12882-016-0319-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ross JA, Mccune WJ, Sanders G. A 50-year old woman with nasal congestion, cough, and dyspnea. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2013;34:188–192. doi: 10.2500/aap.2013.34.3637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zycinska K, Straburzynski M, Nitsch-Osuch A, Krupa R, Hadzik-Błaszczyk M, Cieplak M, Zielonka TM, Wardyn K. Lund-mackay system for computed tomography evaluation of paranasal sinuses in patients with granulomatosis and polyangiitis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;884:13–19. doi: 10.1007/5584_2015_171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaya H, Yilmaz S, Sezgi C, Abakay O, Taylan M, Sen H, Demir M, Akkurt ZM, Senyigit A. Two cases of extrapulmonary onset granulomatosis with polyangiitis which caused diffuse alveolar haemorrhage. Respir Med Case Rep. 2014;13:32–36. doi: 10.1016/j.rmcr.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malavieille F, Page M, Ber CE, Christin F, Bonnet A, Rimmele T. The acute pulmonary renal syndrome: An unusual presentation of granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Rev Mal Respir. 2014;31:636–640. doi: 10.1016/j.rmr.2013.12.005. (In French) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kang CY, Liu CT, Wang YJ, Li TZ. Clinical data analysis and chest radiographic features of Wegener's granulomatosis with pulmonary involvement. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2010;30:786–788. (In Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaffo AL. Diagnostic approach to ANCA-associated Vasculitides. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2010;36:491–506. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vega LE, Espinoza LR. Predictors of poor outcome in ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV) Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2016;18:70. doi: 10.1007/s11926-016-0619-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kawakami T, Shimosaka R, Takeuchi S, Soma Y. Importance of appropriate location and frequency of biopsy for cutaneous manifestations in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:1388–1390. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu XL, Song W, Sui X, Song L, Qn DU, Wang X. Radiological and clinical features of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Ba. 2016;38:617–620. doi: 10.3881/j.issn.1000-503X.2016.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Geeter F, Gykiere P. (18)F-FDG PET/CT imaging in granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Hell J Nucl Med. 2016;19:5–6. doi: 10.1967/s0024499100331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feragalli B, Mantini C, Sperandeo M, Galluzzo M, Belcaro G, Tartaro A, Cotroneo AR. The lung in systemic vasculitis: Radiological patterns and differential diagnosis. Br J Radiol. 2016;89:20150992. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20150992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castañer E, Alguersuari A, Andreu M, Gallardo X, Spinu C, Mata JM. Imaging findings in pulmonary vasculitis. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2012;33:567–579. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mahajan V, Whig J, Kashyap A, Gupta S. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage in Wegener's granulomatosis. Lung Indi. 2011;28:52–55. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.76302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lohrmann C, Uhl M, Kotter E, Burger D, Ghanem N, Langer M. Pulmonary manifestations of wegener granulomatosis: CT findings in 57 patients and a review of the literature. Eur J Radiol. 2005;53:471–477. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2004.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ananthakrishnan L, Sharma N, Kanne JP. Wegener's granulomatosis in the chest: High-resolution CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:676–682. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodrigues AJ, Jacomelli M, Baldow RX, Barbas CV, Figueiredo VR. Laryngeal and tracheobronchial involvement in Wegener's granulomatosis. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2012;52:231–235. doi: 10.1590/S0482-50042012000200007. (In English, Portuguese) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Uppal S, Saravanappa N, Davis JP, Farmer CK, Goldsmith DJ. Pulmonary Wegener's granulomatosis misdiagnosed as malignancy. BMJ. 2001;322:89–90. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7278.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lynch JP, III, Tazelaar H. Wegener granulomatosis (granulomatosis with polyangiitis): Evolving concepts in treatment. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;32:274–297. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1279825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.