Polymerase gamma −1 (POLG1) is a nuclear gene that encodes mitochondrial DNA polymerase gamma, necessary for mitochondrial function, replication and repair. Mutations in POLG1 have a variable phenotypic expression including Parkinsonism, sometimes with epilepsy and posterior column dysfunction [1,2]. We report two siblings with complicated levodopa-responsive juvenile-onset Parkinsonism due to a novel POLG1 mutation.

A brother and sister developed slowness and stiffness at ages 18 and 19 respectively. Their mother had no neurological problems, and their father was absent. They were diagnosed with Parkinsonism and had good levodopa responsiveness, but developed disabling dyskinesias within months of treatment. They were examined 3 years after symptom onset, when off treatment for 2 weeks (Video). They had signs of Parkinsonism including bradykinesia, rigidity and gait problems and the brother was more severely affected. Carbidopa/levodopa 25/100 was administered under observation, resulting in severe dyskinesias (Video). Their examination was also significant for dysarthria, and proprioceptive, pin prick loss in both lower extremities. The brother was non-ambulatory and his sister had a wide-based ataxic gait. Cognitive testing in the brother was difficult due to communication difficulties, but his sister had no cognitive deficits. Routine blood tests as well as ceruloplasmin, ferritin, vitamin E, α-fetoprotein, vitamin B12 and folate levels were all normal. EMG and nerve conduction studies demonstrated generalized sensorimotor axonal neuropathy in the sister. MRI of the brain was normal. Genetic testing for spinocerebellar ataxias and mutations known to cause Parkinsonism (PINK1, PRKN, LRRK2, PLA2G6 and ATP13A2) were negative. Rectal biopsy for neuronal intranuclear inclusion body disease showed no inclusions. The brother had dysphagia for secretions leading to tracheostomy and he died in a nursing home at age 29.

Supplementary video related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2016.06.013.

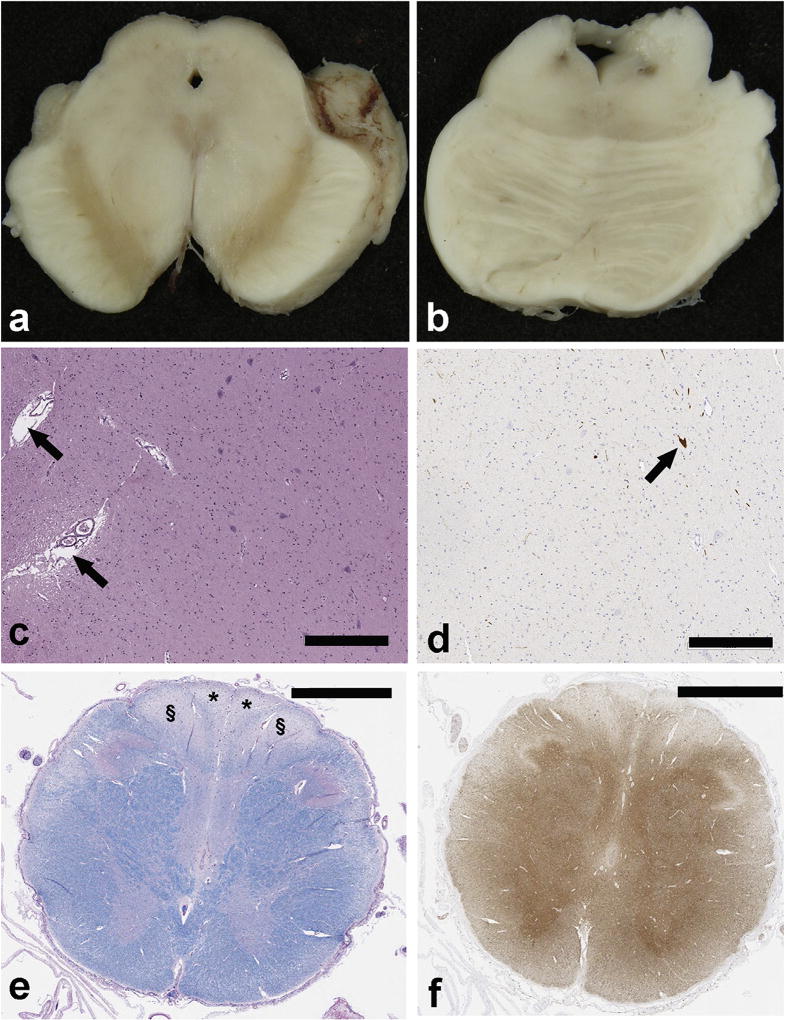

At autopsy there was absence of neuromelanin pigment in the substantia nigra (Fig. 1a) and severe neuronal loss (Fig. 1c), but normal pigmentation in the locus ceruleus (Fig. 1b). There were no neuronal ubiquitin, tau, α-synuclein or p62 inclusions on immunohistochemical stains. Tyrosine hydroxylase immunostaining confirmed neuronal loss in the nigra (Fig. 1d). Other nuclei vulnerable to neurodegeneration in parkinsonian disorders, including the locus ceruleus, dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus and the basal nucleus of Meynert were unremarkable. There was mild gliosis and mild neuronal loss with sparse axonal spheroids in the subthalamic nucleus and the globus pallidus, but no tau immunoreactive neuronal or glial inclusions. These findings are consistent with “pure nigral degeneration.” [3] The upper cervical spinal cord showed posterior column degeneration affecting myelin (Fig. 1e) and axons (Fig. 1f) with fiber loss symmetrically affecting both gracile and cuneate fasciculi.

Fig. 1.

a) Neuromelanin pigment is absent in the substantia nigra bilaterally, b) Dark neuromelanin pigment is bilaterally visible in the locus ceruleus. c) H & E stain shows paucity of neurons in the substantia nigra and dilated perivascular spaces (arrows) due to neuropil atrophy. d) Tyrosine hydroxylase immunohistochemistry confirms paucity of dopaminergic neurons (arrow) in the substantia; nigra. e) Luxol fast blue stain of the cervicomedullary junctions shows bilateral and symmetrical myelin pallor in the cuneate tracts (§) and gracile tracts (*). f) The posterior column tracts also have axonal loss with. (neurofilament immunohistochemistry bars: c and d = 300 µm; e and f = 2 mm).

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood using standard procedures. Protein coding exons for POLG1, PARK2, PARK6, and exons 31, 35 and 41 of LRRK2 were amplified using PCR amplification, and sequenced by Sanger sequencing on an ABI 3730×l genetic analyzer. No variants were identified in PARK2, PARK6, or LRRK2. Within POLG1 we identified a single heterozygous variant in the pol domain (p.E856K; based on accession NM_002693.2). This variant is not reported in the Human Gene Mutation Database, dbSNP138 and from the Exome Variant Server, NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project (ESP), Seattle, WA representing at least 13,000 individual alleles. We have also checked ExAC for this variant in POLG1 (June 2016; ExAC data and browser Version 0.3.1). This variant was absent from >120,000 chromosomes.

These two siblings had juvenile-onset levodopa-responsive Parkinsonism with rapid progression, lack of resting tremor, presence of head tremor and proprioceptive loss. Both siblings had profound and disabling levodopa-induced dyskinesias. This occurred in the absence of other signs of mitochondrial cytopathy such as ophthalmoplegia and myopathy. The pathology of pure nigral degeneration has been previously reported in POLG mutations; however, the patients in that report did not have clinical signs of Parkinsonism [2]. It was this combination of pure nigral degeneration and posterior column degeneration that led to screening for POLG1 mutations in these siblings. A novel mutation, p.E856K, was detected in the polymerase domain of POLG1, which may be responsible for this phenotype. The reasons for this being a pathogenic mutation are 1) it is proximal to the other pathogenic mutations in POLG1; 2) it is absent from 6503 controls; and 3) the pathology and phenotype are very similar to other POLG1 mutation carriers. While a single heterozygous mutation (such as ours) has been shown to cause Parkinsonism [1], it is possible that we may have missed a second POLG1 mutation, as the whole exome sequencing methods used in our studies would miss large structural re-arrangements. There are several reports of various POLG1 mutations causing progressive external ophthalmoplegia [4] and other symptoms such as dysphagia or epilepsy. In some of these reports Parkinsonism may have been a relatively minor part of a larger syndrome and also their age at onset was in later years. Similar to our family, Davidzon et al. have reported a pair of siblings (2 sisters) with early-onset Parkinsonism and peripheral neuropathy [5]. These sisters were compound heterozygous for two missense mutations in the POLG1 gene, a novel G737R mutation and the R853W mutation. One sister developed oral dyskinesia due to levodopa. It is notable that this report of POLG1 associated early onset Parkinsonism was related to apparently recessive mutation; while we have only found a single heterozygous mutation it is conceivable that additional mutations exist in POLG1 in these patients that are not detectable using the current approach.

In summary, this report illustrates two important points: 1) POLG1 mutations should be considered in all patients with juvenile-onset Parkinsonism and should be included in genetic testing along with PINK1, PRKN, DJ1, PLA2G6 and ATP13A2 and 2) POLG1 mutations may be responsible for a unique phenotype of a severe neuropathy with or without posterior column dysfunction in the setting of juvenile Parkinsonism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Mehta reports a personal fee from Corporate Meeting Solutions for CME on dystonia. He has served as a consultant for Acorda therapeutics, Cynapsus, Merz pharma, Allergan and US world Meds.

Dr. Dickson is the Robert E Jacoby Professor of Alzheimer’s Research, and he receives research support from the NIH (P50-AG016574; P50-NS072187; P01-AG003949; P01 NS084974) as well as CurePSP: Foundation for PSP|CBD and Related Disorders and the Mangurian Foundation. Dr. Dickson is an editorial board member of Acta Neuropathologica, Annals of Neurology, Brain, Brain Pathology, and Neuropathology, and he is chief editor of American Journal of Neurodegenerative Disease and International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology.

Dr. Morgan has received honoraria for speaking for Impax and Teva. He has served as a consultant for Abbvie, Acorda, Cynapsus, Impax, Lundbeck, National Parkinson Foundation, Teva, UCB. He has also received compensation for serving as an expert witness in various neurological legal cases. He has served as a site PI or sub-I for clinical trials with Abbvie, Acadia, Acorda, Biotie, CHDI, Cynapsus, Impax, Kyowa, Lundbeck, NIH, NPF, PSG, and Serina.

Dr. Singleton serves as an editorial board member for Movement Disorders, Brain, Lancet Neurology, Neurogenetics, Neurodegenerative Diseases, Journal of Parkinson’s disease, Journal of Huntington’s disease, and Annals of Neurology. Dr. Singleton is on the Scientific Advisory Board of the Michael J Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s disease and the Lewy Body Dementia Association.

Dr. Sethi reports personal fees from Merz Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from Teva, personal fees from Impax Labs, personal fees from Veloxis, personal fees from Lundbeck, personal fees from Synosia, grants from NIH, grants from NPF, grants from Kyowa, grants from Acadia, grants from Abbvie, outside the submitted work.

We are grateful to the patients for giving their consent to be video taped for publication.

We would like to thank Ava Mahloogi for the gene sequencing at the Laboratory of Neurogenetics, National Institute on Aging, Bethesda, MD, 20892, USA. Supported by P50-NS72187 (DWD) and the Mangurian Foundation (DWD).

Footnotes

Financial disclosures

Dr. Majounie has no disclosures to report.

Author contributions

A - Study concept and design.

B - acquisition of data.

C - analysis and interpretation.

D - critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

E - study supervision.

Dr. Mehta – A, B, C.

Dr. Dickson – B, C, D.

Dr. Morgan – B, C, D.

Dr. Singleton – B, C, D.

Dr. Majounie – B, C.

Dr. Sethi – A, B, C, D, E.

Contributor Information

Shyamal H. Mehta, Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ 85259, USA.

Dennis W. Dickson, Department of Neuroscience, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL 32224, USA

John C. Morgan, Department of Neurology, Medical College of Georgia, Augusta, GA 30912, USA

Andrew B. Singleton, Molecular Genetics Section, National Institute on Aging, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA

Elisa Majounie, Molecular Genetics Section, National Institute on Aging, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Kapil D. Sethi, Department of Neurology, Medical College of Georgia, Augusta, GA 30912, USA

References

- 1.Luoma P, Melberg A, Rinne JO, Kaukonen JA, Nupponen NN, Chalmers RM, Oldfors A, Rautakorpi I, Peltonen L, Majamaa K, Somer H, Suomalainen A. Parkinsonism, premature menopause, and mitochondrial DNA polymerase gamma mutations: clinical and molecular genetic study. Lancet. 2004;364:875–882. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16983-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tzoulis C, Tran GT, Schwarzlmuller T, Specht K, Haugarvoll K, Balafkan N, Lilleng PK, Miletic H, Biermann M, Bindoff LA. Severe nigrostriatal degeneration without clinical Parkinsonism in patients with polymerase gamma mutations. Brain. 2013;136:2393–2404. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oyanagi K, Nakashima S, Ikuta F, Homma Y. An autopsy case of dementia and Parkinsonism with severe degeneration exclusively in the substantia nigra. Acta Neuropathol. 1986;70:190–192. doi: 10.1007/BF00686071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brandon BR, Diederich NJ, Soni M, Witte K, Weinhold M, Krause M, Jackson S. Autosomal dominant mutations in POLG and C10orf2: association with late onset chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia and Parkinsonism in two patients. J. Neurol. 2013;260:1931–1933. doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-6975-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davidzon G, Greene P, Mancuso M, Klos KJ, Ahlskog JE, Hirano M, DiMauro S. Early-onset familial Parkinsonism due to POLG mutations. Ann. Neurol. 2006;59:859–862. doi: 10.1002/ana.20831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.