Abstract

Though cementum of the tooth root is critical for periodontal structure and tooth attachment and function, this tissue was not discovered and characterized on human teeth until a full century later than enamel and dentin. Early observations from the 17th to the 19th centuries by Marcello Malpighi, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, Robert Blake, Jacques Tenon, and Georges Cuvier founded a confusing and conflicting nomenclature that obscured the nature of cementum, often conflating it with bone. Advances in microscopy and histological procedures yielded the first detailed descriptions of human cementum in the 1830s by Jan Purkinje and Anders Retzius, who identified for the first time acellular and cellular types of cementum, and the resident cementocytes embedded in the latter. Comparative anatomy studies by Richard Owen and others over the latter half of the 19th century identified coronal and radicular cementum varieties across Reptilia and Mammalia. The functional importance of cementum was not appreciated until detailed anatomical studies of the periodontium were performed by G.V. Black and others in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These early studies on cementum laid the foundation for more advanced understanding of cementum ultrastructure, composition, development, physiology, disease, genetics, repair, and regeneration throughout the 20th and into the 21st centuries.

Keywords: Cementoblast, Periodontal attachment, Periodontal ligament, Root cementum, Dentin, Connective Tissue

Introduction

The cementum of the tooth root provides attachment between the root proper, and the surrounding periodontal ligament (PDL) and alveolar bone of the socket (1–4). Human teeth feature two major types of cementum, the acellular and cellular cementum, which are distinct in location and function. Acellular cementum anchors principal fibers of the PDL to the cervical root surface, and is critical for tooth attachment and periodontal function. Cellular cementum encases the apical portion of the root and provides an adaptive role in maintaining the tooth in its occlusal position. Out of the three hard tissues found in human teeth, cementum was the last discovered, long after widespread recognition of the enamel and dentin layers. This is largely due to its small size and close anatomical relationship to the root dentin. However, while the invention of more powerful microscopes was a necessary antecedent, the narrative was not as straightforward as that. The story of the discovery of cementum, smallest of dental tissues, is epic in scope, depending on contributions from an international cast of renowned researchers over the course of centuries, occurring at a time of seismic shifts in scientific progress by humankind, involving misconceptions, misnomers, and the upending of scientific dogma, and keeping pace with the march of technological progress into the modern age (Figure 1).

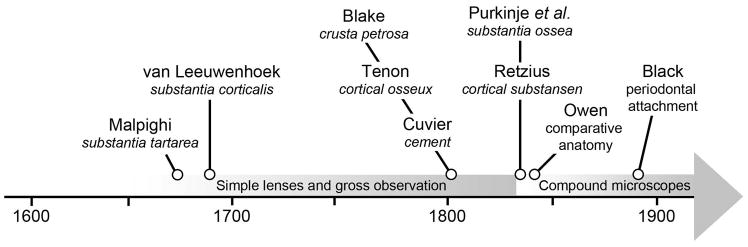

Figure 1. Timeline of discovery of cementum.

This timeline summarizes major contributions to the discovery and understanding of cementum in the 17th through 19th centuries that are discussed in detail in the text. Using simple lenses, Malpighi described a substantia tartarea and van Leeuwenhoek identified a substantia corticalis in the 17th century. By the turn of the 19th century, observation of the dentition of herbivorous animals led Blake to describe a crusta petrosa, Tenon a cortical osseux, and Cuvier a cement layer. The advent of the compound microscope allowed Purkinje and colleagues to discover substantia ossea on human teeth, and Retzius to further expound on this cortical substansen. Owen took the powerful approach of comparative anatomy to understand vertebrate dentitions, including cementum. The functional importance of cementum could not be fully understood until detailed studies of the periodontium by Black at the end of the 19th century. These early studies laid the foundation for more advanced understanding of cementum ultrastructure, composition, development, physiology, disease, genetics, repair, and regeneration throughout the 20th and into the 21st century.

A brief history of dental anatomy from the ancient world to the Renaissance

Though the ancient world is marked by a paucity of dental literature, there is evidence that dentistry was practiced in ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Phoenicia, Etruria, Greece, Rome, in the middle east in the ancient Hebrew and Islamic worlds, and in China and Japan (5–12). In classical Greek culture, we can trace the progressive increase in knowledge of dental anatomy and physiology. Hippocrates (c. 460-c. 370 B.C.), who espoused a rational approach to medicine, made numerous references to toothaches and dental disease, and had some knowledge of tooth development, though his treatise, On Dentition, still propagated numerous folk beliefs, superstitions, and crude ideas, such as that teeth arise from a “glutinous increment from the bones of the head and jaw” (11–13). Aristotle (384-322 B.C.), the greatest philosopher of ancient Greece, and called by some the first naturalist, wrote widely on biology and his Historia Animalium is considered a touchstone in comparative anatomy (14). Despite making novel observations on shapes and numbers of teeth in numerous types of animals, Aristotle made incorrect (but easily testable) assumptions, such as that men had more teeth than women (11, 12, 15). Galen (130–200 A.D.) was the foremost physician of the ancient world, and his ideas directed medical thought and practice for centuries, until the dawning of the Renaissance (16). Despite a poor understanding of human physiology (e.g., advocacy for the humours or temperaments of Hippocratic medicine), Galen made some skilled observations and interpretations of human anatomy, some pertaining to the oral cavity. Galen realized that teeth formed during gestation, yet remained hidden in their alveolar crypts until after birth. Further, Galen marveled at what would now be described as the functional anatomy of the tooth types, noting the usefulness of incisors for cutting and the molars for grinding, and the importance of both hardness and roughness in molar function, and the occlusal relationship between opposing teeth of the maxilla and mandible. Galen’s thoughts on roots of teeth were particularly stimulating, presaging discovery of cementum by more than a millennium, but appreciating the importance of a strong attachment of the root to the alveolar bone: “Moreover would one not also marvel that the teeth are bound to the alveoli with strong ligaments (periosteum), especially at the roots where the nerves are inserted and marvel more if this were a work of chance, not art?” (12, 16–18).

The Renaissance brought an appreciation for careful observation over philosophical conjecture and dogma, revolutionizing understanding of human anatomy and physiology. The world’s first known book devoted to dental therapeutics, the Zene Artzney (19), was printed in Germany just prior to the anatomical studies of Vesalius and Eustachius, and would be reproduced many times in the following decades (20). In his groundbreaking 1543 work, De humani corporis fabrica, Flemish anatomist Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564), broke with long accepted but inaccurate ideas of Aristotle and Galen on the human dentition (21, 22). Vesalius demonstrated that teeth were not solid bone, including a plate illustrating teeth in section, revealing the hollow pulp chamber within (Figure 2A). Vesalius made additional insights regarding the numbers and types of teeth, variable numbers of roots, the frequent absence of the wisdom teeth, and the ability of teeth to feel sensation. Vesalius’s work was severely criticized by his contemporary, Bartolomeo Eustachio (Eustachius; 1520–1574), an Italian anatomist sometimes called the “Father of Dental Anatomy” (23). This antagonism of Vesalius likely had to do with Eustachio’s patronage by the Vatican (he was the physician to several cardinals), and thus inability to challenge the official Galenic teachings of the Roman Catholic Church (24, 25). Eustachio’s Libellus de Dentibus is described as the first book devoted to the anatomy and function of teeth (26)(Figure 2B). Over the course of 30 illustrated chapters, Eustachio reported many important discoveries on dental form and function, including their development in utero, and the organization of the two hard tissues, enamel on top of dentin, which he described as like “the husk of an acorn.” Like Galen, Eustachio appreciated the periodontal attachment, observing that “the roots of all the teeth are so well attached to their respective sockets that the teeth can hardly be budged. Ligaments attached to each root provided added stability. Moreover, there are extremely strong fibers attached to the roots; these provide a firm connection to the socket.” While admiring the strength of the attachment, Eustachio had no way of knowing there was a third hard tissue of the tooth playing a critical role in this anchorage. Ambroise Paré (ca. 1510–1590), a French barber-surgeon known for his battlefield medicine and introduction of humane surgery techniques (27), provided another early and prescient insight into tooth attachment, “that their adherence to the jaw is caused by a ligament which goes from the root of the tooth to the jaw.” Paré’s dental therapeutic instincts have been touted as ahead of their time because of a rational approach and aim to reduce the pain of those he treated; he promoted use of oil of vitriol (sulfuric acid) or aqua fortis (nitric acid) to relieve toothache, in part a holdover from the superstition that tooth-worms caused caries (28). The discovery of cementum, as with many other microscopic structures of the teeth, was not realized until the advent of the microscope in the 17th century.

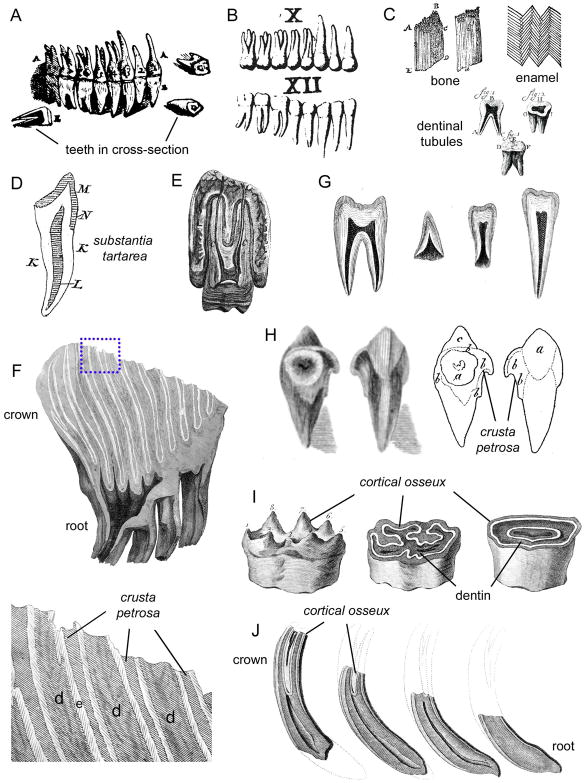

Figure 2. Discovery of cementum in the 17th–18th centuries.

(A) Diagram of the human dentition, including teeth in cross-section, by Andreas Vesalius (Vesalius, 1543). (B) Illustration of the human dentition from the Libellus de Dentibus (Eustachio, 1563). (C) Figures prepared by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, describing the structure of bone, the tubular nature of dentin (the toothbone made up of “pipes”), and the grain of ivory (decussation of enamel) in human teeth (van Leeuwenhoek, 1677; van Leeuwenhoek, 1687). (D) Diagram of a human tooth by Marcello Malpighi (Malpighi, 1700; Figure 4 from his Opera Posthuma). Malpighi denoted the crown enamel (M, called by the author substantia filamentosa), as well as the distinct substantia tartarea (K; cementum) covering the length of the root. (E) Human molar in situ in the alveolar bone socket as illustrated by John Hunter (1778), revealing the pulp cavity and root canals, but no detail regarding the outer surface of the roots or the nature of the periosteum (periodontal ligament). (F) Elephant molar section by Robert Blake, showing the complex folded crown and root. The blue dotted box indicates a region of the illustration blown up below to show tissue details. The dentin (referred to as the “bony part of the tooth” by the author) is indicated by d, the cortex striatus (enamel; e) is the overlaid whitish layer, and the crusta petrosa (cementum) fills the space between adjacent enamel plates (Blake, 1798). (G) Illustrations of normal human teeth by Robert Blake, with no indication of cementum on the roots (and no mention by the author of cementum as part of normal human dental anatomy), and (H) diagram of a human tooth by Robert Blake, illustrating a case of hypercementosis. (I) Diagrams of horse molars and incisor by Jacques Tenon, indicating the layers of cortical osseux (cementum; shaded area), enamel (whitish layers), and dentin (cross-hatched layers) (Tenon, 1797). The leftmost image indicates a lower third molar upon eruption, with cementum-covered cusps intact, while the middle image indicates the same tooth after attrition, revealing the complex layers. The right image indicates similar tissue layering in the incisor tooth. (J) Figure by Tenon of the equine incisor in cross-section and over time, indicating attrition at the incisal tip and progressive development of the root (Tenon, 1797). Enamel is covered by a layer of cortical osseux, i.e. cementum.

The Age of Enlightenment: Cementum discovered

English philosopher, experimental physicist, and inventor, Robert Hooke (1635–1703), popularized the use of the microscope to study biological specimens in his groundbreaking book, Micrographia, published by the Royal Society in London (29). Using his single lens microscopes and complex compound microscopes, Hooke was the first to describe the cell as a biological unit, as well as microscopic structures in insects, wood, and various crystals, all displayed in detailed copperplate engravings (30, 31). This work was the first publication that illustrated objects seen under the microscope, and was majorly influential in popularizing science to the public, including to Dutch tradesman Antonie van Leeuwenhoek.

Van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723) operated a draper’s shop in Delft, Holland, and it has been speculated that the use of a magnifying glass to inspect cloth led to his interest in microscopy, which blossomed into an unusual scientific career (32). Leeuwenhoek had no scientific training before cultivating an interest in lensmaking and observation of minutiae that eventually led him to be regarded as the “Father of Microbiology.” Van Leeuwenhoek’s simple microscopes consisted of a single double convex lens fitted between two plates, with the object of interest placed on a needle-like holder that could be adjusted (nearer, farther, rotated, etc.) for observation (33). While van Leeuwenhoek is often described as an individualist in terms of microscope design and construction, there is evidence that he followed the detailed protocol for lens preparation presented by Hooke in his preface to Micrographia (30, 34, 35). Van Leeuwenhoek’s microscopes are commonly estimated to magnify from 70X to around 250X, depending on the individual lens quality, though some calculations or practical demonstrations estimate upwards of that (34). Van Leeuwenhoek’s findings captured the attention of the Royal Society in London (for which Robert Hooke served as Curator of Experiments and later, as Secretary), and over the course of several decades, he made numerous groundbreaking discoveries with his hundreds of tiny microscopes, including his most famous description of “animalcules” in tooth scrapings. In a 1677 report to the Royal Society, van Leeuwenhoek made accurate descriptions of the structure of bone (including perhaps osteocytes and their processes, and concentric rings of Haversian canals), provided nuanced sketches of the decussation pattern of the enamel on human teeth, and was the first to recognize dentinal tubules, which he described as “small pipes” and numbered at 4,822,500 in a human tooth (Figure 2C) (36). In a later letter, van Leeuwenhoek made similarly detailed descriptions of the teeth of animals, including appearance of dentin in tusks of pigs and elephants, (37). Later authors speculated that Leeuwenhoek recognized the presence of cementum on animal teeth based on his mention of a substantia corticalis (from the Latin for cortical substance) on the teeth of a calf, though the dearth of any figures indicating the location and appearance of the material make this difficult to ascertain (12, 38, 39).

Marcello Malpighi (1628–1694), a physician and academic in his early professional career, pursued anatomical studies later in life as a Professor in Bologna, Italy. Several of his discoveries bear his name, e.g., the Malpighi layer of the skin and Malpighian tubules in insects, and he made extensive observations on the structures of plants as well (40, 41). Like his contemporaries, Hooke and van Leeuwenhoek, Malpighi is thought to have made his discoveries using a simple, single lens microscope, in combination with his formidable skill at dissecting. Although not amongst his better known discoveries, Malpighi made careful observations of the microstructures of what he considered the two parts of the teeth, what he called the substantia filamentosa (enamel) and substantia ossea (dentin). Based on his collected anatomical works published after his death in 1700 (but referencing observations from ca. 1667), Malpighi was the first to recognize another substance covering the root (Figure 2D). Of the structure of the tooth, Malpighi remarked that it was doubtful that the substantia filamentosa covering the upper part of the tooth also invested the remainder of the root, “For the crust which is observed, seems to be a matter more tartarous than filamentous.” [translated from the Latin] (41). In this simple statement, the substantia tartarea appears as the first name by which cementum was labeled. No substantial detail was revealed by Malpighi, however, and it seems that no one capitalized on this discovery over the next century. Throughout the eighteenth century and the first third of the nineteenth century, despite publication of more than 200 works on dentistry and dental tissues in Europe (42), human teeth were widely thought to be composed of the two hard tissues, enamel and dentin (38). In a work representative of these times, Thomas Berdmore (ca. 1740–1785), dentist to King George III of England, said in no uncertain terms that “The roots of the teeth consist of one uniform substance” (43).

The Scottish surgeon and dentist, John Hunter (1728–1793), published his comprehensive work on development and pathology of teeth in 1778 (44). Hunter included some novel observations based on his experiments, including the almost completely inorganic nature of the enamel, and that the plant dye, madder, could be fed to animals and would potently stain only the new layers of dentin, showing the concentric deposition of this tissue (an experimental technique presaging use of the madder-derived alizarin dye by modern day scientists to label the mineralization front of teeth and bones). Hunter gave little thought to tooth attachment, hypothesizing (in a section spanning only seven lines) that roots are surrounded by a periosteum that comes from the alveolus, and depicting the region around the tooth root as merely a dark empty space in his accompanying plates (Figure 2E). However, the illustration of teeth in situ in their bony sockets was novel for the time, allowing Hunter to exhibit the blood supply and innervation of the pulp in his cross-sectional diagrams. Hunter’s periosteum theory of tooth attachment later found favor with surgeon and zoologist Thomas Bell (1792–1880), who stated that “the periosteum of the maxillary bones, after covering the alveolar processes, dips down into each alveolar cavity, the parities of which it lines,” and going further to suggest that this periosteum is “reflected over the root of the tooth, which it entirely covers as far as the neck, at which part it becomes intimately connected with the gum” (45). Clearly these authors were contemplating the mechanism of tooth attachment, however they did not have the means to do more than speculate based on their limited powers of observation. John Hunter made many other useful clinical observations, e.g. recognizing swelling around the tooth roots (what he termed spina ventosa) and anchylosis between tooth and alveolar bone in his practice. Unfortunately, Hunter also forwarded many questionable prerogatives on the clinical practice of dentistry, including extraction of decayed teeth in order to boil and replace them back into the patient, and generally injurious attempts to transplant teeth. In retrospect, Nasmyth lamented that many of the practices Hunter ushered into dentistry “tend to a direct increase in suffering, and in some cases even to a gradual destruction of life” (12).

In his lengthy dissertation published in 1798 and translated in 1801 as “An Essay on the Structure and Formation of the Teeth in Man and Various Animals,” physician Robert Blake (1772–1822) identifies cementum for a second time, calling it the crusta petrosa, or “rocky crust” (46, 47). Blake’s discourse ranges far and wide, on topics of anatomy of teeth and the nature of the tissues, primary and secondary teeth and the process of eruption, and cases of diseased teeth he treated in patients. Blake seems to delight in puncturing fallacies of his day, even (or especially) when correcting errors by authorities like John Hunter. Blake in particular spends much time describing crown or coronal cementum in graminivorous (grass-eating) animals, especially focusing on elephants. In several beautifully detailed illustrations of longitudinally sectioned elephant molars, Blake identified the crusta petrosa covering the complex cusps (Figure 2F). Importantly, Blake realized the existence of root cementum, at least in some species: “The crusta petrosa not only covers that part of the tooth which appears through the gum, but also that part of it that remains in the socket, and in a few instances I have observed a small quantity of it on the roots of the teeth of very old horses.” Blake makes an insightful inference on the function of root crusta petrosa, hypothesizing that it is for “the membranes to adhere to, and also to prevent the sockets from being injured by the violent motion performed in grinding.” This may be one of the earliest instances of the linkage of root cementum to its actual attachment function, though Blake does not dwell on it, or possess the means to explore it further.

Blake spends the vast majority of his writing on the crusta petrosa considering the formation and function of the coronal variety of cementum, rather than that associated with the root. Even with his careful studies and fastidious descriptions, Blake completely missed the presence root cementum on human teeth (Figure 2G), noting that a case of apparent hypercementosis on a maxillary premolar was “the only instance I have met with, or even heard of, where a crusta petrosa was deposited on a human tooth” (Figure 2H). British anatomist and dentist Alexander Nasmyth later relayed that “The essay of Sr. Blake must always be regarded as the best work on the subject of the period at which it was written,” adding that “His ideas respecting the ‘crusta petrosa’ were original at the time, and have since been generally acquiesced in” (12).

Jacques Rene Tenon (1724–1816) was a French surgeon and pathologist, most famous for discovering the fascia bulbi, or capsule of Tenon, that envelops the posterior portion of the eyeball. In studies on horse dentition, Tenon recognized the presence of a cortical osseux (confusingly translated from the French to cortical bone, but referring to cementum) covering the complex cusps of the molar crown (Figure 2I). Tenon elaborated that this “bony shell” was softer than bone, greyish in color, and extended into all the folds of enamel in the complex shape of the horse crown (48). He believed this layer to be an ossification of the membrane investing the tooth. By carefully studying and measuring the wear on equine teeth over time, Tenon described the complicated and changing patterns of tissue layers on the occlusal surfaces, with cortical osseux as the outer layer, and underneath the enamel, and then dentin (Figure 2J).

Jean Leopold Nicolas Frederic Cuvier (better known as Georges, or Baron Cuvier ) (1769–1832) is a celebrated French naturalist and comparative anatomist who, in the early 19th century, did much to establish the field of vertebrate paleontology, and founded the theory of extinction of species- animals from a “world previous to ours” (49). Cuvier produced a large body of work on the osteology of both extant and extinct species, notably studying the skeleton and dentition of elephants in great detail, and establishing that African and Indian elephants were distinct species. More importantly, Cuvier recognized that mammoths were an extinct but related clade to the extant elephants. Cuvier’s groundbreaking paleontological work extended to discovery that the “Ohio Animal” unearthed in the United States was yet another extinct relative to the elephant, naming it Mastodon, describing and naming the extinct ground-dwelling giant sloth of Paraguay as Megatherium, and identifying and naming the flying reptile Pterodactyl and the giant marine reptile Mosasuarus. In his comparative anatomy studies of Asian and Indian elephants and their extinct brethren, jaw and dental anatomy provided critical insights into species differences. Like Tenon, Cuvier appreciated the advantage of studying the dentition of herbivores over their entire lives, because of the complex dental morphologies that are continually changing due to opposing processes of deposition and attrition (50). Cuvier coined the term cement to describe the material joining the plates in the compound crown of the elephant molar, replicating Blake’s observations on crusta petrosa. The modern term cementum is derived from Cuvier’s neologism, though notably, that author inferred the function of the cement to be joining the plates of the crown, rather than in attachment of the tooth root. He also hypothesized the cement was produced from the same lamina that secreted the enamel, though it became thick, spongy, and reddish during cement secretion. Cuvier not only documented the presence of cement on teeth from many species, but performed experiments to test its dissolution in acids, response to heating, and other insults. Cuvier, however, was off the mark when he declared that cement in the majority of species had no apparent organization, but resembled a crystallized tartar on the tooth surface. Cuvier’s protégée, M. Rousseau, made the more embarrassing misstep of asserting that root cement itself was nothing more than a deposition of dental tartar (12, 51).

The observations by Blake, Tenon, and Cuvier on cementum were reported in anatomical texts and reference books of the day, with the hypothesis that ruminant animals required this coronal cementum layer for greater resistance of teeth to grinding (52). German anatomist, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1752–1840), in his comparative anatomy text from 1827, spent many pages on the observations of Blake’s crusta petrosa and Cuvier’s cement, noting its presence on grinders of elephants, horses, cows, sheep, and hippopotami, but not according to him, on those of rhinoceroses (53). Blumenbach elaborated on the function as he understood it: “The food of the graminivorous quadrupeds is subject to a long process of mastication, before it is exposed to the acid of the stomach. The teeth of the animals suffer greater attrition during this time, and would be worn down very rapidly but for the enamel which is intermixed with their substance [cementum].” The possibility that cementum was commonly present on human teeth was not broached.

Isolated observations from anatomists in the early nineteenth century indicates that some began to suspect the presence of a third substance on the roots of human teeth. Blumenbach and fellow anatomist Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring (1755–1830) reported a “horny substance” on roots, however like Blake, assumed it to be a pathological condition (38, 54). One exception was Carl Joseph von Ringelmann (1776–1854), who compiled a book of dentistry published in Germany in 1824 (55). Though he borrowed much from Sömmering’s work on dental anatomy, Ringelmann disagreed about cementum, observing that the horny substance was present on all human teeth, partially covering the roots, an observation that likely arose from his observation of cellular cementum on the apex. Speaking from practical experience, like Robert Blake before him, Ringelmann also noted that an excessive amount of cementum on the root apex (i.e., hypercementosis) made extraction difficult. Denton has noted that Ringelmann is likely the first of the dental profession to confirm cementum as a normal constituent on roots of human teeth (38).

Enter the histologists: Discovery of cementum on human teeth

Observations of the latter 18th and early 19th centuries were made largely from macroscopic observations of animal and human teeth, with some using simple lenses. As the invention of the simple microscope allowed Leeuwenhoek and Malpighi to discern microstructures of the teeth, improvements in microscopy again accelerated the study of tooth anatomy. Simon Plössl (1794–1868), an Austrian optician, and a microscope and telescope designer, set up shop in Vienna in 1823. Plössl was recognized as one of the finest microscope designers of his day, and greatly progressed compound microscope function through improvement of the achromatic lenses and by making eyepiece adjustment easier.

A Plössl microscope was provided to the Breslau laboratory of Czech anatomist and physiologist, Jan Evangelista Purkinje (or Purkyně; 1787–1869), by the year 1832 (38, 56, 57). Purkinje was a pioneer anatomist and physiologist immortalized by his influential studies of the heart (Purkinje fibers), brain (Purkinje cells), and vision (Purkinje tree, images, and shift). Purkinje and his students began studying tooth anatomy using the Plössl microscope by 1835. Purkinje’s advances in tissue preparation were pivotal, and his pupil Oschatz is credited with inventing the first plate microtome for histological sectioning. Other innovations included advanced fixation techniques, staining of tissues for better contrast, procedures for decalcifying bones and teeth in acidic solutions to allow cutting of thin sections by microtome, and grinding resin-embedded calcified samples to thin, transparent layers for imaging by microscope (58–61). These novel approaches allowed for much more detailed microscopic observations of biological samples, teeth included. Purkinje’s student, Meyer Fränkel, in his 1835 dissertation included eight finely detailed cross sections of human teeth (62). Fränkel’s report focuses more on the structure and composition of enamel and dentin, especially recognizing the tubular structure of dentin. Fränkel describes experiments performed in Purkinje’s laboratory, including capillary action drawing ink into the dentinal tubules, and effects of acid dissolution on the calcified dental tissues. On the outer surface of the human tooth root, Purkinje and colleagues report a layer of true osseous substance, the substantia ossea. Here, finally, the human tooth root cementum makes its entrance onto the stage of scientific history. Fränkel’s diagrams present incredibly detailed renderings of the teeth and their substantia ossea (Figure 3A–C), which is described as a laminated but otherwise unstructured substance (in contrast to the decussation of enamel and tubules of dentin). The substantia ossea is drawn thin at the neck of the tooth and increases in size near the apices, wherein one can see osseous corpuscula, or bony bodies (Figure 3C), afterwards referred to as corpuscles of Purkinje for a time (and later understood to be the cementocytes of cellular cementum). The dissertation by another of Purkinje’s students, Isaac Raschkow, in the same year, featured further histological observations on teeth, including the existence of a bed of nerves adjacent to the odontoblast layer, the so-called plexus of Raschkow (63). In his work, Raschkow focused on the origin of the dental follicle and stages of tooth development. His detailed studies described the invagination of oral epithelium and developmental changes in tooth germ morphology that all dental students now learn as bud, cap, and bell stages of tooth development. In this developmental series, Raschkow dispelled many earlier ideas that the tooth derived from the mucous membrane or nerve, and his description of the “adamantine organ” destined to produce enamel was likely the first identification of the enamel organ as a separate entity.

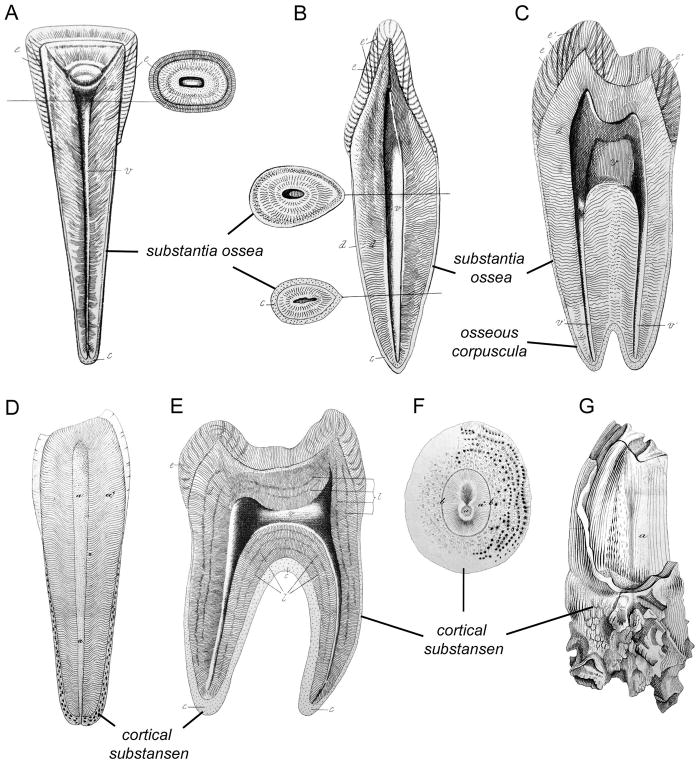

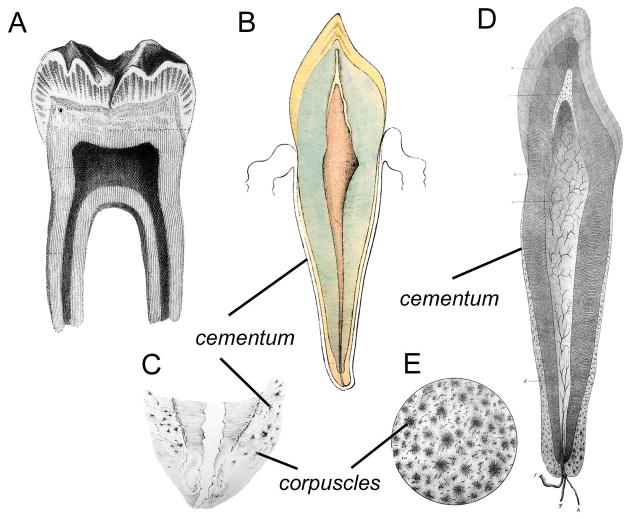

Figure 3. Discovery of human cementum in the 19th century.

(A) Diagram of a longitudinal coronal section of a middle lower incisor by Fränkel (1835) showing dentin (d), enamel (e), and thin substantia ossea (acellular cementum) covering the root. The transverse cross-section shows the tissues of the crown. (B) Another section of an incisor (with a more sagittal orientation) by Fränkel shows another view of the substantia ossea (cementum) distribution, including two cross-sections through the root. (C) Longitudinal section of a lower premolar by Fränkel showing substantia ossea (cementum). Fränkel denotes the presence of osseous corpuscula (cementocytes) by dots within the substantia ossea. (D) Diagram of a longitudinal cut of a human molar by Retzius (1837), showing the dentin-pulp complex (a) and cortical substansen (cementum). Note the inclusion of cells in the apically located cementum. (E) Longitudinal section of a molar by Retzius showing thin acellular cortical substansen (cementum) on the cervical root and thick cellular cortical substansen on the apical surfaces and in the furcation region between roots. (F) Another diagram from Retzius showing a transverse section of the root of a human maxillary canine exhibiting an unusually thick layer of cortical substansen (cementum), including numerous cells and their extending processes. (G) Cow molar by Retzius featuring excessive secretion of cortical substansen (cementum), showing root and crown cementum, with a portion cut away to reveal the enamel (a) underneath.

In 1833, the already very accomplished anatomist, Anders Retzius (1796–1870), traveled forth from the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, Sweden, attending the Congress of Naturalists at Breslau and meeting with Purkinje. This was a turning point in his career, directing Retzius to anatomical studies employing the high powered microscopes of the day (64). While Purkinje and colleagues progressed on their studies of dental histology, Retzius was simultaneously studying microscopic tooth structures. Retzius has been immortalized for his discovery of incremental growth lines in the enamel, that now bear his name as striae of Retzius. However, he was surprised to find that Purkinje had beaten him to it by publishing on the tubular structure of tooth dentin (65). Both had actually been beaten by more than a century by Leeuwenhoek on that count. Retzius, however, made several insightful observations on the dentin based on careful tissue preparations and experimental manipulations, e.g. confirming that dentinal tubules gave off branches, noting the existence of the peritubular dentin sheath around tubules, and speculating that the tubules could be involved with circulation of fluids or nutrients (12, 66). In fact, though Purkinje and Fränkel had beaten Retzius to publication by two years, the work of Retzius was a much richer and more detailed study, at more than four times the length and including comparative observations of the dentitions of some 28 species of mammals, reptiles, and fish.

Retzius also described the cortical substansen (from the Swedish for “cortical substance”) covering roots of human teeth, perhaps taking a cue from J.F. Meckel’s (1781–1833) nomenclature for this rindensubstanz (from the German for “cortical substance”), though Retzius was also familiar with earlier work on the cement by Cuvier. This new cortical layer in human teeth began at the termination of enamel and was an extremely thin stratum, increasing in thickness towards the apex. Retzius recognized that cementum grows throughout life, being relatively thicker in the elderly. Experiments revealed the composition to be of “cartilage and of osseous earth,” what we today would recognize as the organic and inorganic components, respectively.

The diagrams of Retzius are even more delicately rendered than those of Fränkel, clearly depicting zones of acellular and cellular cementum (Figure 3D, E). A transverse section of a tooth in old age illustrates a massive layer of cellular cementum, with embedded cementocytes and their cellular processes clearly depicted (Figure 3F). Of the cementocytes, Retzius noted that numerous tubes pass into and from them (i.e. the dendritic cell processes), giving them the appearance of irregular stars. In teeth where roots were not fully formed and cortical substansen was exceedingly thin, Retzius was unsure of the inclusion of cells; this was the acellular cementum.

Retzius examined teeth from about two dozen other species, noting comparative structures of enamel, dentin, and cementum. He recognized the coronal cementum of Blake, Tenon, and Cuvier, on teeth of hares, beavers, sloths, sheep, horses, and cows, and was perhaps the first investigator to identify root cementum in these and several other species. In many species with cellular cementum on crown or root, Retzius commented that the corpuscula (cementocytes) varied widely in size and shape, with some elongated, tube-shaped, or nearly round. As perhaps the first comparative study of cementum in different species (see the next section for further comparative anatomy studies), Retzius made important discoveries of the “extreme” anatomies of highly derived teeth, such as teeth with no enamel and abundant cortical substansen (e.g. seal, walrus, and three-toed sloth). Retzius included a brilliantly detailed image of a cow molar with excessive secretion of cortical substansen, showing root and crown cementum, with a portion cut away to reveal the enamel underneath (Figure 3G). Though he observed that teeth attached by a ligament tended to feature root cortical substansen, while those directly attached to jawbones did not, Retzius does not seem to have guessed at the function of cementum being related to tooth attachment. Rather he favored the opinion that the minute tubes running through the cortical substansen may serve to deliver nutrients to the tooth after closure of the apex, presuming these tubes communicated with those in the dentin. Following his numerous discoveries and intense regimen of microscopy, Retzius’s eyesight deteriorated, forcing him to abandon his anatomical studies (64, 67).

Comparative anatomy of cementum

The revolutionary insights of Purkinje and Retzius culminated in the first detailed descriptions of the cementum on human teeth, and a sense of the varieties of cementum across the animal kingdom. Here was a minute structure located on every human tooth th, at heretofore, was universally overlooked. The first detailed descriptions of cementum were those of coronal cementum of elephants and horses by Blake, Tenon, and Cuvier. Retzius first described root cementum in these and other species. It was only a matter of time before anatomists expanded their studies to the wider animal kingdom.

Richard Owen (1804–1892) was the preeminent British naturalist of the first half of the 19th century, establishing the field of paleontology in England, coining the term Dinosaur, crystallizing the comparative anatomy concepts of homology and analogy (68), and founding the British Museum (Natural History). Early in his career, Owen had a collaborative relationship with fellow naturalist Charles Darwin, analyzing South American fossils Darwin sent back from his voyages on the H.M.S. Beagle (69), including the extinct giant ground-dwelling sloth Megatherium first identified by Georges Cuvier. While Owen’s decades of comparative anatomy work and conceptions of the vertebrate archetype were cornerstones employed by Darwin to support his theory of evolution by natural selection, a combination of museum politics, professional jealousies, and scientific disagreements with Darwin and his followers, especially T.H. Huxley, led to Owen’s scientific legacy becoming tarnished and obscured (70).

After a conventional early career path as a surgeon’s apprentice, Owen’s professional life took a defining turn in London, and he focused on studies of comparative anatomy for the remainder of his career. In 1832, Owen received an appointment as curator of the specimen collection of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, which included John Hunter’s massive collection of skeletons and anatomical preparations. In 1837, Owen was elected Hunterian Professor by the Royal College of Surgeons and was charged with delivering the series of Hunterian lectures on comparative anatomy and physiology, a comprehensive multi-year series that referenced to the extensive specimen collection (71–73). Material from Owen’s lecture series from 1837–1842 formed the basis for a remarkable book, Odontography. Odontography is comprised of two volumes that include 655 pages of text and 168 meticulously illustrated plates that detailed number, shape, development, attachment, replacement, and histology of teeth in living and fossil vertebrates, including more than 80 species of fish, more than 70 species of reptiles, and nearly 200 species of mammals. In short, Odontography was like nothing that came before, and there has been no equal since.

Unlike many comparative anatomists of the day who were critical of the use of microscopy, Owen embraced it, even serving as founding president of the Microscopical Society in London. Owen’s justification for including dental histology as part of his osteological approach to comparative anatomy was made plain in his own words, “that the teeth, by their microscopic structure, as well as their more obvious characters, form important, if not essential aids to the classification of existing, and the determination of extinct species of vertebrate animals.” In Odontography, Owen built on the recent findings of Purkinje and Retzius and others, matching and sometimes surpassing their fine histological details and colossally widening the scope of their findings through inclusion of a wide array of vertebrates. Owen’s microscopy proved critical for several important findings. Owen proposed that “The tissue, which forms the chief part of the body of the tooth” be universally given the specific term of dentine, as the myriad names employed in the anatomical literature (e.g. ivory, bone of the tooth, tooth-bone, knochensubstanz, etc.) confused and obfuscated the matter. Owen also coined osteo-dentine (bone-like) and vaso-dentine (highly vascular) as modified forms of dentine found in some species. By the same token, Owen likely influenced the nomenclature of cementum, forgoing Blake’s crusta petrosa and Tenon’s cortical osseux (and similar “bony” labels from Purkinje and Retzius) in favor of Cuvier’s cement, perhaps a nod to his fellow comparative anatomist and paleontologist.

Other than reporting cement structures across the vertebrates, what were Owen’s important findings? His identification of cement on extinct reptiles such as Icthyosuarus (Figure 4A) established an ancient origin for the tissue. Owen discussed the varied arrangements of tooth attachment amongst vertebrates, typically direct ankylosis (either acrodont or pleurodont) in many fish and reptiles, where mammals feature a true socket with fibrous attachment (thecodont), an arrangement termed a gomphosis. While Owen did not extensively analyze the dental histology of Crocodilia, he did record the presence of root cement and observed that unlike the majority of extant reptiles, they exhibited anterior teeth implanted in distinct sockets with a thecodont style of attachment (Figure 4B), even though these teeth were continually replaced throughout life. At the time, however, the role of root cementum in tooth attachment was not yet anticipated.

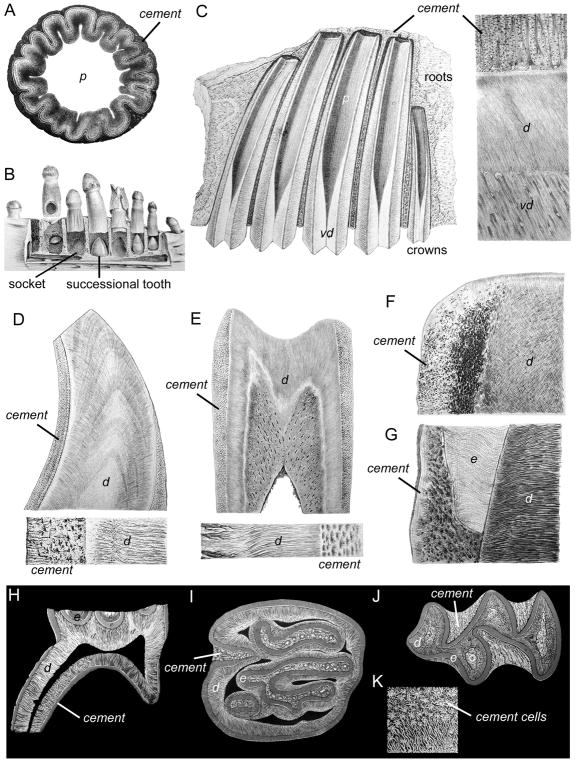

Figure 4. Comparative anatomy of cementum.

Figures adapted from Richard Owen’s Odontography (1840) and selected to indicate the scope of living and extinct vertebrate dentition analyzed by Owen. (A) Transverse section of the base of a tooth from Ichthyosaurus communis (a marine reptile from the late Triassic-early Jurassic period) showing cement (cementum) external to dentine. (B) Middle portion of the lower jaw of Alligator niger showing distinct sockets (gomphosis attachment) and the process of continuous succession. (C) Section of the upper jaw and five molars of Megatherium cuvieri (giant ground-sloth endemic to South America in the late Pliocene through the Pleistocene), indicating root cement (cementum) covering vaso-dentine (vd). Magnified section to the right shows dentine (d), vaso-dentine (vd), and cement, including vascular loops. (D) Longitudinal section of a tooth from a Cachalot (sperm whale) showing dentin and coronal cement (cementum), with a higher magnification image below detailing the cement corpuscles (cementocytes). (E) Longitudinal section of a tooth from Bradypus tridactylus (three-toed sloth) showing dentin and coronal cement (cementum), with a higher magnification image below. (F) A section of upper tusk from Mastodon giganteus showing thick cement (cementum) covering the dentine (d). (G) Longitudinal section of molar from Phascolomys vombatus (wombat) exhibiting overlap of coronal cement (cementum) and enamel (e) at the tooth neck. Cement corpuscles (cementocytes) with numerous cell processes are abundant in the cement. (H) Vertical section of the molar of Pteromys volucella (flying squirrel) displaying root cement (cementum), as viewed by Owen under reflected light on a dark background. (I) Transverse section of a molar of Castor fiber (beaver) showing coronal cement (cementum) filling in the spaces amongst the complex crown morphology. (J) Transverse section of a molar of Arvicola amphibia (water vole) showing coronal cement (cementum). (K) Magnified portion of cement (cementum) of a calf (Bos Taurus) showing cement cells (cementocytes) and their network of tubes. According to Owen’s labeling: d, dentin(e); vd, vaso-dentine; od, osteodentin(e); e; enamel. All images courtesy of the Ohio State University Rare Books and Manuscripts Library (Columbus, OH).

Owen’s histological achievements shine greatest in the section on mammals, where he paints a broad canvas on the varieties of teeth in extant and extinct, Old and New World mammals (Figure 4C–J). Owen discovered thick, vascularized forms of cement on some mammals, e.g. horse, sloth, and ruminant, commenting that “The most remarkable modification of mammalian cement is presented by the thick layer of that substance which invests the molars of the extinct magatherium” due to the extensively looped vascular canals that penetrated almost to the dentine (Figure 4C). Owen reported that reptiles and mammals featured cement “excavated by minute radiated cells” the corpuscles of Purkinje that we now know as cementocytes (Figure 4K). Intriguingly, Owen realized that “Cement always closely corresponds in texture with the osseous tissue of the same animal,” noting that the cellularity of bone and cementum paralleled one another.

In Odontography, Owen provided a comprehensive work that formed the basis for much subsequent research, contributed to the establishment of dentistry as scientific discipline (74), and has a lasting value to dental researchers even in the present day due to its scope and detail (70). Other works on the comparative dental anatomy that came out prior to or were contemporary with Owen’s Odontography lacked its breadth and depth, and the detailed illustrations and histological details provided in abundance by Owen, and these other works recognized the crusta petrosa of crowns, but not the cement of the roots [e.g. (53, 75–77)]. Those that followed Odontography suffered similar inadequacies, being limited in scope and were sometimes overly derivative of Owen’s work [e.g. (78–81)].

Some misconceptions about cementum arose and were propagated in the academic literature of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Purkinje and Retzius and those researchers following in their footsteps were much taken with the apically located cementum, providing numerous detailed illustrations of the star-shaped “corpuscles of Purkinje” and their intercellular connections (see for example, Figure 3C, E and Figure 4K). It was not immediately clear to them whether cells were present in the thin cervical cementum as well, and some illustration seem to show cells getting smaller and more indistinct towards the neck of the tooth, e.g. Figure 3. Owen commented that in developing teeth “the cement is so thin that the Purkinjean cells are not visible.” By the end of the century, further observations confirmed that the more cervical cementum lacked cells altogether in most cases: “Where the cementum is very thin, as, for instances where it commences at the neck of a human tooth, it is to all appearances structureless, and does not contain any lacunae, and therefore no protoplasmic bodies” (81). In the other extreme, Arthur Hopewell-Smith (ca. 1865–1931) doubted the physiological existence of cells in cementum at all, and was of the opinion that the apical cementum is “devoid of life” and that “normally the lacunae with their containing corpuscles are absent; that when they do appear, they are symptomatic of a previous inflammation…” (82, 83).

Richard Owen, for his part, was convinced of a very thin and structureless cementum layer covering the crowns of many vertebrates, including humans (39). The question was still not entirely settled several decades afterward, when Charles Sissmore Tomes (1846–1928; son of dentist John Tomes) opined, that despite counter-arguments, cementum “is present in a rudimentary condition upon the [crowns of] teeth of man, &c., as Nasmyth’s membrane.” (81). The so-called Nasmyth’s membrane was later discovered not to be cementum at all, but rather the primary enamel cuticle, or the compressed remnants of epithelial cells known as the reduced enamel epithelium [as summarized in (84)]. Tomes admitted as much after this had been proven experimentally, updating his text on dental anatomy to reflect the new findings (85).

Increasing recognition of cementum in the dental profession

Following the discoveries from Purkinje and Retzius, the presence of cementum on human tooth roots was immediately confirmed by fellow anatomists, including Johannes Müller (1801–1858) in Germany, and dental surgeon John Tomes (1815–1895) and naturalist Richard Owen in England (38, 39). Knowledge of cementum spread to scientists throughout Europe and America and entered the dental literature in the decade following these scholarly works, though with variable speed and acceptance. The presence of scientists with an active interest in anatomy (who were sometimes practicing dentists as well) in England (e.g., John Tomes and Alexander Nasmyth) and Germany (e.g., C. Joseph Linderer) likely contributed to the ready acceptance of this new information into the body of dental knowledge (12, 86, 87).

In a publication for dental surgeons published in London in 1839, William Robertson remained completely oblivious to the discovery of human cementum, stating plainly that “A tooth consists of two parts,” and describing the enamel and remaining fang of the tooth (the term dentin, or dentine, had not yet become commonplace), and a surrounding periosteum connected to the tooth (88). Robertson’s anatomical images likewise gave no hint of another tissue on the root dentin (Figure 5A). In contrast, Lintott in his brief 1841 publication targeted to medical practitioners and students, incorporates the discovery and distinguishes between thinner cementum at the neck and thicker cementum containing those “corpuscles of Purkinje,” i.e. cementocytes (Figure 5B, C). Lintott comments on the increasing apposition of cementum throughout life, and the “serious obstacle to the removal of the tooth” in cases of cementum exostosis or ankyloses in the aged. Like Lintott, Goddard published a practical manual for dentistry, though pressed in the U.S. and with a somewhat more ambitious production with an oversize format and inclusion of extensive plates (13). Goddard plainly states that the “tooth is composed of four distinct and totally different structures, which I will describe separately, and in order of their hardness; Enamel, Ivory, Cementum or crusta petrosa, and Dental pulp.” In the brief section on the characteristics of cementum, Goddard reflects that cementum “will be found to be very analogous to bone, but wants the vessels, Haversion canals and other constituents of true bone.” Goddard’s depiction of cementum on an adult incisor adheres closely to the images published by Retzius (Figure 5D, E).

Figure 5. Depictions of cementum in early dental textbooks.

(A) A cross-section of an adult molar from a dental manual by Robertson (1839), with no indication of the existence of root cementum. (B) A “modern” but simplistic drawing of an adult human canine tooth from a textbook by Lintott (1841), depicting the thin (acellular) cementum at the neck and thicker cementum at the apex of the root. (C) A sketch of the cellular cementum and its corpuscles of Purkinje (cementocytes) by Lintott. (D) A cross-section of an incisor from Goddard (1845) indicating tooth root cementum, and (E) a magnified view of the corpuscles (cementocytes). All images courtesy of the Ohio State University Health Sciences Library Medical Heritage Center (Columbus, OH).

Both Lintott and Goddard comment on the ongoing debate on the origin of the cementum layer. Lintott lays out the debate as one hypothesis claiming it to be an “ossification of the investing membrane of the root of the tooth,” (i.e. the dental follicle or sac) with the counter-argument supposing cementum to be a “true secretion from this membrane” (86). Goddard comes down firmly on the side of secretion “by the periosteal covering of the fang.” On the topic of function or purpose of the cementum on human teeth, authors of early dental textbooks remained silent (13, 86).

At the time of the founding of the world’s first dental college in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1840, the average dentist was unlikely to be aware of the existence of cementum on human teeth. This knowledge was likely slow to spread through the dental profession, with the topic inconsistently included in mainstream dental texts (38), and the informality of dental education throughout the U.S. and Europe in most of the 19th century (89). However, a survey of various types of medical references from the 19th and early 20th centuries reveals that cementum was increasingly appreciated, and discussed predominantly as either crusta petrosa (typically mid-19th century) or cement/cementum (latter 19th century), or using both terms interchangeably, with various other nomenclatures failing to make a lasting impression on the lexicon. Publications touching on the presence and structure of cementum included general anatomical and embryological texts (53, 90–93), encyclopedias (94–96), dental and medical journals (97–99), handbooks of dental anatomy and practice of dentistry (13, 86, 100–103), and reports on comparative anatomy (as described above), both in Europe and North America.

By the end of the 19th century, the term cementum was predominant and crusta petrosa had all but disappeared. Cementum was routinely included and described in detail, in the subsequent new generations of dental histology and embryology texts in the late 19th and early 20th century [eg., (81, 85, 104–108)]. The importance of cementum for tooth function was increasingly recognized (as described in detail in the following section). Frederick Bogue Noyes said it best: “The function of the cementum cannot be too strongly emphasized and must be continually borne in mind.” (105). In this era, cementum was generally discussed as a single and homogenous tissue, without particular distinction between the thin cervical or thick apical varieties, other than to note the presence of cells in the latter (85, 106, 109–117). As time went on, a shifting perspective considered cervical and apical cementum as two sub-types often described as primary or secondary cementum, respectively (118–120). By the mid-20th century, textbooks and the dental scientific literature commonly differentiated these into acellular and cellular cementum (121–125), and these remain the preferred terms to this day. However, primary and secondary cementum are still acceptable, and the truncated form cement still appears in the anthropological and paleontological literature. This modern terminology reflects a dichotomy not only in name, but we also ask whether the acellular and cellular cementum types are the same or distinct tissues in terms of origin and development (1, 4). Additional scientific approaches such as electron microscopy have further parsed the cementum terminology to specify acellular extrinsic fiber cementum (AEFC) and cellular intrinsic fiber cementum (CIFC), though these are largely reserved for ultrastructural studies (84, 126, 127).

As the concepts and labels for cementum changed over the first half of the 20th century, so did the nomenclature for cells of the cementum. While the cementoblasts acquired their name by the end of the 19th century (101, 128, 129), the corpuscles of Purkinje gradually transitioned to cement corpuscles (85, 101, 105, 109, 112, 114, 115, 117), cement cells (118, 119), and ultimately to cementocytes (121, 124, 125, 130), paralleling the terminology for bone osteocytes.

On cementum attachment and function, and the periodontal ligament

By the time the structure of human cementum had been discovered, detailed analysis of dentin and enamel stretched back more than a century. Few had turned their attention to the tissues surrounding the tooth, what we now know as the PDL, but which was then referred to as the dental periosteum, alveolo-dental membrane, or peridental membrane. In 1839, a few short years after the discoveries of Purkinje and Retzius, Nasmyth summarized the current state of knowledge on the dental periosteum or membrane of attachment, reflecting that on this topic “the opinions of writers on the teeth are contradictory in the extreme” (12). However, the debate centered more on the nature of the membrane, and not its function or relation to the tooth. Lintott, in his 1841 text aimed at dentists and dental students, glossed over the subject completely, explaining that “the limits of this little work do not permit, neither does its object require, a complete enumeration and description of the membranes of the teeth,” underscoring the ignorance and lack of importance attributed to these tissues at the time (86). In Odontography, Owen briefly references his thoughts on the function of cementum, hypothesizing that “its chief use is to form the bond of vital union between the denser and commonly unvascular constituents of the tooth and the bone in which the tooth is implanted” (39). Note that the dental periosteum is nowhere to be found in the statement, and likewise is not depicted in any of the histological plates found in Odontography.

By 1874, Luman C. Ingersoll (1832–1911), future Dean of the University of Iowa College of Dentistry, was writing as an editorial in the Dental Cosmos, the preeminent dental publication in the U.S., “A plea for the peridental membrane” to be further studied (131). Ingersoll’s plea seems to have fallen on deaf ears, as eleven years later at the annual meeting of the American Dental Association (ADA) he chided the attendees: “In looking over the pages of the Dental Cosmos for the whole period of its publication, I do not find a single article referring to the peculiar structure of the peridental membrane except one penned by myself eleven years ago” (129). Ingersoll made a valid argument that the dental community should take an interest because “if the alveolo-dental membrane fails the whole structure is gone.”

The comprehensive monograph, A Study of the Histological Characters of the Periostium and Peridental Membrane, published by G.V. Black in 1887, must have come as a welcome relief to his friend Ingersoll (101). Greene Vardiman (G.V.) Black (1836–1915) was one of the founders of modern dentistry in the United States, and served as the second Dean of the Northwestern University Dental School. Black’s contributions to dentistry are numerous and diverse, including the foot-driven dental drill, the first detailed protocol on cavity preparations, exhaustive experimentation to optimize preparation and use of dental amalgam, and a number of books that were touchstones of their era, including classic texts such as Descriptive Anatomy of the Human Teeth and Operative Dentistry (107, 132, 133).

Though best known for the accomplishments enumerated above, G.V. Black made a significant but largely overlooked contribution to the understanding of the connective tissues of the teeth in this 1887 work, which was the first detailed microscopic study of the PDL and periodontal apparatus (134). In order to accomplish the task, Black reported more than a decade devoted to developing the equipment and methods for processing, embedding, decalcifying, and sectioning of tissues. As a preface to his work on the peridental membrane, Black provided nuanced and sophisticated descriptions of endochondral and intramembranous bone formation. While it was recognized at the time that the periosteum covering bone surfaces had some sort of bone-forming potential, Black’s careful observations identified the osteoblasts as being “endowed with a special bone-forming power” and present only in the loosely attached portions of the periosteum. Black had a particular interest in the periosteum firmly attached to the underlying bone, where he noted fibers exiting the bone and that these fibers were actually compact bundles of even smaller fasciculi; this is an accurate description of the collagen fiber-fibril organization. These bundles of perforating fibers passing between bone lamellae were previously identified by anatomist William Sharpey (1802–1880), who recognized they could be teased out when bone lamellae were pulled asunder (135). These became known in the literature as “Sharpey’s perforating fibres” or just Sharpey’s fibres. Intriguingly, Sharpey recognized that “Perforating fibres exist abundantly in the crusta petrosa of the teeth” but said no more on the subject. By G.V. Black’s time, a bone-forming potential had been ascribed to Sharpey’s fibers. Based on his careful observation of osteoblasts and attached versus unattached periosteum, Black upended this dogma, stating “The function of these fibers, it seems to me, is physical and entirely passive; that of giving firm attachment to the periosteum and the tissues it supports.” He argued that “I should, therefore, regard the term osteogenic fibers consisting of osteogenetic substance, applied to them by Sharpey and adopted by many histologists, as an error.” Critically, G.V. Black recognized, perhaps for the first time, that the insertion of these fibers into the cementum of the tooth surface and into the alveolar bone was the key structural element joining these tissues into a functional unit, what we know as the periodontium. On how this union was formed developmentally, he recognized the “fibers are not part of the bone per se, but are the accident of the formation. In other words, the method of making form hold upon the bone, is the implantation of the fibers by building the bone around them.” Thus the architecture of the periodontium was mapped by Black, highlighting the arrangement of principal fibers passing from tooth to surrounding bone, the nature of Sharpey’s fibers insertions into cementum and bone, as well as resident cells, blood vessels, and sensory functions (Figure 6A–E). Of the 67 superb hand-drawn diagrams, a full-length section of a kitten incisor is the masterpiece of the bunch (Figure 6A), combining all of these elements into an incredibly detailed and unified whole. The histological depiction of tooth, ligament, and bone, together at last, is striking when compared to previous illustrations of teeth shown in isolation from their functional position and periodontal attachment. G.V. Black understood that “If this arrangement of fibers be studied with reference to the physical functions of the membrane-i.e., that of maintaining the tooth in its position during the strain of normal usage, it will be found that it is the very best that could be devised for the purpose.”

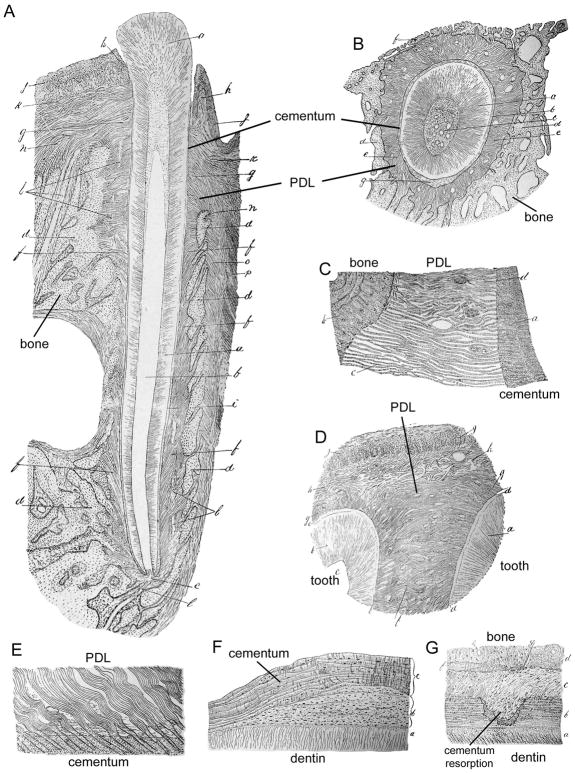

Figure 6. Elaboration of the periodontal attachment function.

Figures adapted from G.V. Black’s A Study of the Histological Characters of the Periostium and Peridental Membrane (1887). (A) Section of a small incisor from a kitten showing the relationship of the tooth to the surrounding periodontia, including detailed depiction of the periodontal ligament (PDL) and alveolar bone. Black noted this tooth was in total only 1/4th inch long. (B) Cross-section of a human incisor tooth illustrating the PDL fibers radiating from the tooth root cementum to the surrounding alveolar bone. (C) Higher magnification image detailing Sharpey’s fibers penetrating the surfaces of alveolar bone and cementum. (D) Black reported that sometimes there was direct connection of principal fibers between adjacent teeth, as shown here in sections from the cervical roots of human central and lateral incisors. (E) Compact bundles of Sharpey’s fibers emerging from the primary cementum were noted to break up into smaller “fasciculi” in this molar taken from an aged man. (F) Cementum hypertrophy in the cellular cementum of a premolar tooth. Black noted that only the first cementum lamella appeared unusual (labeled by the author as b), while subsequent lamellae (c) presented normal thickness. (G) Section of a human premolar showing a “pit-like absorption upon the side of the root” wherein repair cementum has begun to be deposited. All images courtesy of the Ohio State University Health Sciences Library Medical Heritage Center (Columbus, OH).

The monograph holds a wealth of additional insights, particularly in identifying specific cell types and functions. Black performed a detailed survey of the cells in the peridental membrane, for the first time describing and naming the attendant fibroblasts, and recognizing that the “fibers arise under the immediate supervision of cells.” He also gave a detailed account of the cells that he observed secreting the cementum: “The cementoblasts are cement builders are to the cementum what the osteoblasts are to the bone,” but further clarifying that “they have no resemblance to the osteoblasts in form.” Black recognized that cementum grew in lamellar fashion continually throughout life, and that local cementum hypertrophies (Figure 6F) reflected perturbations in this growth process. On osteoclasts, Black’s pioneering observations included that they “dissolve the bone with which they are in contact, probably by secretion of a solvent fluid, making room for themselves, and in this way remove the surface of the bone, i.e. cause its absorption.” Black understood that osteoclasts were part of a normal cycle of bone replacement with osteoblasts, and occasionally resorbed the root surface. In this context, he may have been one of the first to describe reparative cementum in resorption lacunae (Figure 6G). He may have even anticipated the discovery of periodontal stem cells, noting that in the membrane space “there is always a considerable number of undeveloped cells within the meshes of the fibrous tissue in young subjects, but not very many in the old.” Ultimately, G.V. Black laid the essential groundwork for understanding the role of cementum in the larger periodontium, which was an essential antecedent to understanding dental development, function, disease, and potential for regeneration.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

The quest for understanding tooth form and function has been ongoing since the ancient world, with pioneers from each age bringing to bear new technologies and insights that allow us to push our understanding further. Whereas classical cultures could use only the unaided eye, the Renaissance brought simple lenses, followed by more powerful compound microscopes in the 19th century. Insights into the existence and identity of cementum followed on the course of these technological advances, borne out on the curiosity of anatomists, physiologists, surgeons, and dentists (Figure 1). While the invention of more powerful microscopes and advanced processing techniques were necessary, the narrative of the discovery of cementum was not as straightforward as that. First recognized only as a coronal tissue on the teeth of some herbivores, after its discovery on human tooth roots, cementum was commonly thought of as a type of bone, reflected by names like cortical osseux, substantia ossea, and cortical substansen.

These early studies of cementum laid a foundation that was essential for more advanced understanding of cementum in the years afterward. Though periodontal diseases were recognized prior to its discovery, the role of cementum in these etiopathologies, as well as the reparative capabilities of cementum, have been topics of intense study for more than a century (136–145). More sophisticated imaging techniques, including scanning and transmission electron microscopy, have laid bare the ultrastructure of cementum, revealing a level of detail unimaginable to earlier generations of microscopists (84, 126, 127, 146–151). The developmental biology and composition of cementum has been elucidated using techniques such as protein chemistry, immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridization, and proteomics (1–4, 152–158). Studies on cementum physiology and its influence on microstructure and growth have revealed not only the nature of disease states (1, 159–163), but have also provided insights into animal habits, as by analysis of cementum growth increments (164–169). Molecular biology has brought new tools, where cell tracking, targeted gene knock-out, and transgenic over-expression approaches allow us to target and tinker with cells and essential genetic ingredients of cementum (1, 170–173).

Despite all the progress on understanding cementum, additional fundamental questions remain, including on the origin of cementoblasts, the factors directing cementum formation, potential functions for cementocytes, and prospects for directing cementum regeneration (1, 3, 4, 130). The debate on cementum identity extends to the present day, when we still ask whether cementoblasts are a type of osteoblasts and cementum is a type of bone (4, 174). These outstanding questions will be answered in time through the development of new technologies and with novel insights from present day and future researchers.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks goes to Martha J. Somerman, whose mentorship over 16 years (and counting) was the inspiration and impetus for my curiosity in dental research, and in cementum in particular. Additional critical inspiration and insight came from publications by and conversations with Thomas Diekwisch, Dieter Bosshardt, and Wouter Beertsen. This work is indebted to George B. Denton for his short thesis, “The Discovery of Cementum,” which served as a blueprint and valuable resource for portions of this paper. Thanks to Eva Åhren (Karolinska Institute, Unit for Medical History and Heritage, Stockholm, Sweden), Stephen Greenburg (National Library of Medicine at the National Institutes of Health NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA), Kristin Rodgers (Medical Heritage Center, Health Sciences Library, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA), and Eric Johnson (Rare Books & Manuscripts Library, Thompson Library, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA) for assistance finding and accessing literature, as well as capturing some of the images included here. Much of the historical research that informed this work was made possible by examination of digitized books and journals on Google Books (books.google.com), the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA; dp.la), and the Hathi Trust Digital Library (www.hathitrust.org), resources making available ancient and out-of-print texts that would otherwise be difficult or impossible to locate. Thanks to Hope K. Crowley for editorial feedback.

References

- 1.Foster BL, Somerman MJ. Cementum. In: McCauley LK, Somerman MJ, editors. Mineralized Tissues in Oral and Craniofacial Science: Biological Principles and Clinical Correlates. Ames, IA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012. pp. 169–192. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foster BL, Popowics TE, Fong HK, Somerman MJ. Advances in defining regulators of cementum development and periodontal regeneration. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2007;78:47–126. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(06)78003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diekwisch T. The developmental biology of cementum. Int J Dev Biol. 2001;45:695–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosshardt D. Are cementoblasts a subpopulation of osteoblasts or a unique phenotype? J Dent Res. 2005;84:390–406. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denton GB. The Most Famous Dental Book. Bulletin of the Medical Library Association. 1935;24:113–123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Topaloglou EI, Papadakis MN, Madianos PN, Ferekidis EA. Oral surgery during Byzantine times. J Hist Dent. 2011;59:35–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mylonas AI, Tzerbos FH. Cranio-maxillofacial surgery in Corpus Hippocraticum. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2006;34:129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mylonas AI, Poulakou-Rebelakou EF, Androutsos GI, Seggas I, Skouteris CA, Papadopoulou EC. Oral and cranio-maxillofacial surgery in Byzantium. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uzel I. Dental chapters of Serefeddin Sabuncuoglu’s (1385–1468?) illustrated surgical book Cerrahiyyetu’l Haniyye. J Hist Dent. 1997;45:107–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corruccini RS, Pacciani E. “Orthodontistry” and dental occlusion in Etruscans. Angle Orthod. 1989;59:61–64. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1989)059<0061:OADOIE>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ring ME. Dentistry: An Illustrated History. 2. New York, NY: Abradale Press, Harry N. Abrams, Inc; 1992. p. 320. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nasmyth A. Researches on the Development, Structure, and Diseases of the Teeth. London: John Churchill; 1839. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goddard . The Anatomy, Physiology and Pathology of the Human Teeth with the Most Approved Methods of Treatment, Including Operations, and the Method of making and Setting Articifical Teeth. Philadelphia: Carey and Hart; 1844. p. 192. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brittain J. Aristotle: The First Philosopher-Naturalist. In: Huxley R, editor. The Great Naturalists. New York City: Thames & Hudson, Inc; 2007. pp. 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cresswell R. Aristotle’s History of Animals: In Ten Books. London: Henry G. Bohn; 1862. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shklar G, Brackett CA. Galen on oral anatomy. J Hist Dent. 2009;57:24–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.May MT. Galen: On the Usefulness of the Parts of the Body. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koutroumpas DC, Koletsi-Kounari H. Galen on dental anatomy and physiology. J Hist Dent. 2012;60:37–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zene Artzney (Artzney Buchlein wider allerlei kranckeyten und gebrechen der tzeen) Leipzig: Michael Blum; 1530. Various. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Proskauer C. The two earliest dentistry woodcuts. Journal of the history of medicine and allied sciences. 1946;1:71–86. doi: 10.1093/jhmas/1.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vesalius A. De humani corporis fabrica libri septem. Basel: 1543. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hast MH, Garrison DH. Andreas Vesalius on the teeth: an annotated translation from De humani corporis fabrica. 1543. Clin Anat. 1995;8:134–138. doi: 10.1002/ca.980080210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bennett GW. The root of dental anatomy: a case for naming Eustachius the “father of dental anatomy”. J Hist Dent. 2009;57:85–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shklar G, Chernin D. Eustachio and “Libellus de dentibus” the first book devoted to the structure and function of the teeth. J Hist Dent. 2000;48:25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simpson D. The papal anatomist: Eustachius in renaissance Rome. ANZ journal of surgery. 2011;81:905–910. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2011.05793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eustachio B. Libellus de Dentibus. Vincenzo Luchino; 1563. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drucker CB. Ambroise Pare and the birth of the gentle art of surgery. The Yale journal of biology and medicine. 2008;81:199–202. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruby JD, Cox CF, Akimoto N, Meada N, Momoi Y. International journal of dentistry. 2010. The Caries Phenomenon: A Timeline from Witchcraft and Superstition to Opinions of the 1500s to Today’s Science; p. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hooke R. Micrographia. London: The Royal Society of london; 1665. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gest H. Homage to Robert Hooke (1635–1703): new insights from the recently discovered Hooke Folio. Perspectives in biology and medicine. 2009;52:392–399. doi: 10.1353/pbm.0.0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gest H. The remarkable vision of Robert Hooke (1635–1703): first observer of the microbial world. Perspectives in biology and medicine. 2005;48:266–272. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2005.0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ford BJ. Antony van Leeuwenhoek: The Discoverer of Bacteria. In: Huxley R, editor. The Great Naturalists. New York: Thames & Hudson, Inc; 2007. pp. 104–110. [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Zuylen J. The microscopes of Antoni van Leeuwenhoek. Journal of microscopy. 1981;121:309–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1981.tb01227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ford BJ. Did Physics Matter to the Pioneers of Microscopy? Adv Imag Elect Phys. 2009;158:27. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gest H. The discovery of microorganisms by Robert Hooke and Antoni Van Leeuwenhoek, fellows of the Royal Society. Notes and records of the Royal Society of London. 2004;58:187–201. doi: 10.1098/rsnr.2004.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Leeuwenhoek A. Letter by Mr. Anthony Leeuwenhoeck. London: The Royal Society; 1677. Microscopical Observations of the Teeth and other Bones: Made and Communicated. (Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society) [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Leeuwenhoek A. Letter to the Royal Society. Apr 4, 1687. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Denton GB. The Discovery of Cementum. Northwestern University; 1941. p. 22pp. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Owen R. Odontography:A Treatise on the Comparative Anatomy of the Teeth; Their Physiological Relations, Mode of Development, and Microscopic Structure in the Vertebrate Animals. London: Hippolyte Bailliere; pp. 1840–1845. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Motta PM. Marcello Malpighi and the foundations of functional microanatomy. Anat Rec. 1998;253:10–12. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199802)253:1<10::AID-AR7>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malpighi M. Opera Posthuma. Amsterdam: 1700. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coles O. A List of Works on Dentsitry Published Between the Years 1536 and 1882. London: John Bale and Sons; 1882. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berdmore T. A Treatise on the Disorders and Deformities of the Teeth and Gums Explaining the Most Rational Methods of Treating Their Diseases. London: 1770. [Google Scholar]