Abstract

Primary care faces challenging times in many countries, mainly caused by an ageing population. The GPs’ role to match patients’ demand with medical need becomes increasingly complex with the growing multiple conditions population. Shared decision-making (SDM) is recognized as ideal to the treatment decision making process. Understanding GPs’ perception on SDM about patient referrals and whether patients’ preferences are considered, becomes increasingly important for improving health outcomes and patient satisfaction. This study aims to 1) understand whether countries vary in how GPs perceive SDM, in patients’ referral, 2) describe to what extent SDM in GPs’ referrals differ between gatekeeping and non-gatekeeping systems, and 3) identify what factors GPs consider when referring to specialists and describing how this differs between gatekeeping and non-gatekeeping systems. Data were collected between October 2011 and December 2013 in 32 countries through the QUALICOPC study (Quality and Costs of Primary Care in Europe). The first question was answered by assessing GPs’ perception on who takes the referral decision. For the second question, a multilevel logistic model was applied. For the third question we analysed the GPs’ responses on what patient logistics and need arguments they consider in the referral process. We found: 1) variation in GPs reported SDM– 90% to 35%, 2) a negative correlation between gatekeeper systems and SDM—however, some countries strongly deviate and 3) GPs in gatekeeper systems more often consider patient interests, whereas in non-gatekeeping countries the GP’s value more own experience with specialists and benchmarking information. Our findings imply that GPs in gatekeeper systems seem to be less inclined to SDM than GPs in a non-gatekeeping system. The relation between gatekeeping/non-gatekeeping and SDM is not straightforward. A more contextualized approach is needed to understand the relation between gatekeeping as a system design feature and its relation with and/or impact on SDM.

Introduction

Primary care is facing challenging times in many countries, mainly caused by an ageing population and increase in the burden of disease. The delivery of care requires a new approach built around the fundamentals of primary care, particularly continuity and care coordination.[1] The need to move to more efficient and patient centric primary care, pressures decision-makers for reform. In western countries, primary care is often the first contact point between the public and the health care system. Strong primary care is often associated with the gatekeeping position of GPs.[2] Strengthening primary care increases incentives for the gatekeeping role of GPs. Most often, GPs are better informed on options for treatments by medical specialists than patients.[3] By performing the gatekeeping role, GPs mitigate supplier-induced demand by handling the asymmetry of information between patients and specialists, limiting the possibility of the specialists to create their own market.

Economic theory places GPs’ gatekeeping role as a restriction on the demand side. In healthcare, patient demand is matched with the medical needs as perceived by the health care professional. Therefore, the GPs’ role is to match the demand of the patients with their medical need, which becomes increasingly complex with the growing number of persons with multiple conditions. By many, the gatekeeping function is considered to promote coordination of care, and is perceived to work well when the GP-patient relationship is based on trust. It is also perceived as a tool for rationing, by limiting access to specialists through regulating referrals. [2][3][4]

For decades, countries like the U.K. and the Netherlands have had a primary care system with a gatekeeping role.[5][6] In the U.K., its introduction was intended to be a response to specialists’ shortage by slowing down the rate of referral to help regulate waiting times for secondary care, while it was seen also as a tool to control costs.[7] However, it is unclear if the intended effects on decreased costs occurred. There is evidence on both sides, showing associations with increases and decreases in healthcare utilization and costs.[8][9]

Gatekeeping has also showed a positive relationship with a reduction in the adverse effects of overtreatment.[10] However, gatekeeping may have “unexpected, serious side effects”, as associations were found with lower survival rates in oncology, potentially caused by delayed diagnosis.[11] There are stakeholders who have been lobbying actively for abolition of gatekeeping believing it limits patient choice. More recently, it has been suggested, “gatekeeping negates the person centered model, patient choice, and shared decision making”.[12][13]

Despite its critiques and confounding evidence, strong primary care systems, with a gatekeeping role in place, have shown associations with improved population health outcomes, reduced socio-economic inequalities, fewer avoidable hospitalizations, and more continuity as perceived by patients.[14][15] Since the early 1990’s, Central Eastern European countries reformed their health care systems by introducing new concepts, such as gatekeeping. However, gatekeeping came along with a reputation as a bureaucratic hurdle to specialized medical services and having generalist doctors with less medical knowledge making key decisions.[10] Irrespective of the GPs’ gatekeeping role intensity in different countries, patients’ involvement in healthcare has been widely recognized by the medical community [16] and needs to be aligned with strategies aimed at promoting efficiency.

In the past decades, SDM has been recognized as an ideal for the treatment decision making process. [17] SDM seems to be of benefit for disadvantage groups, improve cognitive outcomes and quality of life.[18][19][20] Still, general outcomes are yet undetermined. Nevertheless, understanding the GPs’ perception on shared decision making about patient referrals, and whether patients’ preferences are considered, becomes increasingly important. It is also unknown to what extent logistical factors and need influence GPs’ professional behavior with regard to referrals. Additionally, there is no evidence for any association between shared decision-making, the referral practice and the typology of the primary care system, gatekeeping system vs. non-gatekeeping system. Our aim is to investigate these elements. More specifically, our study addresses three research questions, by analyzing 32 countries with different historical background on their healthcare systems typology:

Do countries vary in how GPs perceive shared decision-making (SDM), in deciding upon patients’ referral?

To what extent does shared-decision making in GPs’ referrals differ between gatekeeping and non-gatekeeping systems?

What factors do GPs consider when referring to a medical specialist and how does this differ between gatekeeping and non-gate keeping systems?

Materials and methods

To address the research questions we used the GPs survey data from the cross-sectional QUALICOPC study (Quality and Costs of Primary Care in Europe), which included 31 European countries and Australia, Canada and New Zealand. Data collection took place between October 2011 and December 2013. The aim for each country was to draw a nationally representative sample of GPs with one GP per practice.[21] The GP questionnaire was completed by 7,183 GPs. Details about the study protocol, questionnaire development and data collection, have been published elsewhere.[21][22][23] The study is written within the aims of the QUALICOPC study and its ethical approval. Ethical review was conducted in accordance with the legal requirements in each country. See the S1 Table for an overview of names of ethics committees by country.

Greece and Finland were excluded from our analysis after validating the primary findings with the country coordinators. In Greece, there was a translation error in the question to be analyzed, and in Finland, at the time of the survey, there were some developments in the health care system that impacted the reliability of the physicians’ answers to the questions related to this topic.

To answer the first research question we used the GP’s reported perception on who makes the decision in case of referrals. The participating GPs were asked through the survey to respond 1) if they make the decision, 2) if the patient does or 3) if it is a shared decision.

For the second question, a multilevel logistic model was applied. The response to the question on who decides in case of a referral was dichotomized into 1 (it is a shared decision) and 0 (either the patient of the doctor). We call this variable ‘shared decision making’ (SDM). The model has two levels, with GPs (level 1) clustered into countries (level 2). In step-1, the variable ‘gatekeeping’ (0 for no, 1 for yes) was added to the model. In step 2, controlling variables were added to the model: age and sex of the GP and the practice location—big (inner)city, suburbs, (small) town, mixed urban-rural and rural.

For the third research question we analysed the GPs responses on what patient logistics and need arguments they consider in the referral process, including: 1) the patient’s preference where to go, 2) the travel distance for the patient, 3) the physician’s previous experiences with the medical specialist, 4) comparative performance information on medical specialists, 5) waiting time for the patient and 6) costs for the patient. Each of the 6 items had three answer options: always, sometimes and never. Our analysis focused on the “always” since if considering “always” and “sometimes” as a positive answer, there were almost no differences between countries and between the aspects they take into consideration (see annex 1). We compiled the data based on the responses and benchmarked countries 1) against each other, 2) against the total weighted average, 3) the gatekeeping systems against the total weighted average of the gatekeeping systems and 4) the non-gatekeeping systems against the total weighted average of the non-gatekeeping. To classify whether primary care systems have a gatekeeping system in place or not, the QUALICOPC, OECD and PHAMEU data bases were examined. [24][25] For reasons of consistency the taxonomy of QUALICOPC data was used.

Results

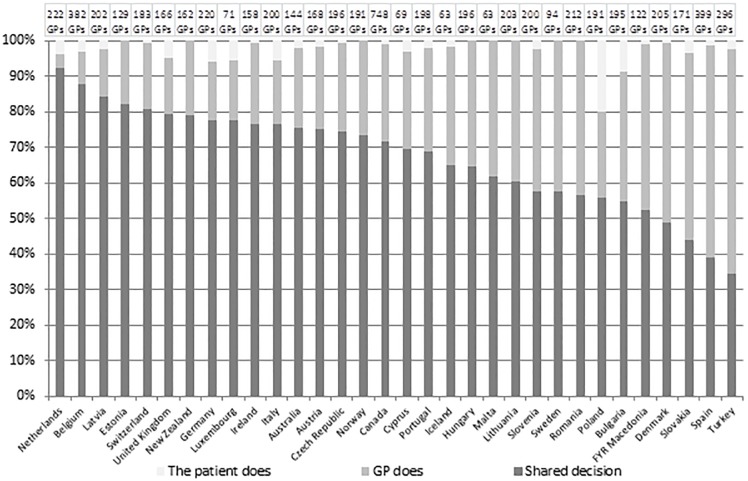

Fig 1 shows the reported levels of referral practice across 32 countries. “SDM” is reported to be most common (levels higher than 50%) in 28 countries. The values range from 92.3% (the Netherlands) to 52.5% (FYR Macedonia). GP-based decision is most common in 4 countries:—Denmark (50.7%), Slovakia (52.6%), Spain (59.9%) and Turkey (63.2%). Patients being the main decision-taker is reported far less frequently. In 25 countries the values range low, from 0.5% (the Czech Republic and Denmark) to 8.7% (Bulgaria) and 19.9% (Poland), while in the remaining 7 countries, the patient never makes the decision.

Fig 1. Answer to the question: In case of referral, who usually decides about where the patient is referred?

The results of our logistic regression analysis are shown in Table 1. The first model (column 2) shows a negative odds ratio for gate keeping, suggesting that GPs in gatekeeping systems are less likely to make shared decisions. This negative relation remains after controlling for a number of variables, such as female doctors and practice location (model 2). Female doctors and those in rural areas are more likely to report that they make shared decisions.

Table 1. Results logistic regression multilevel analyses association between the shared decision making (SDM) levels and gate keeping system.

| Ni = 32; Nj = 6572 | Odds ratio | SE | Odds ratio | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 2.387 | 0.035 | 1.520 | 0.158 |

| Gatekeeping (baseline NO) | 0.865 | 0.053 | 0.859 | 0.055 |

| Age | 1.002 | 0.002 | ||

| Gender—male/female (baseline—MALE) | 1.208 | 0.055 | ||

| Practice location | ||||

| Suburbs (baseline—Big city) | 1.342 | 0.089 | ||

| Small town (baseline—Big city) | 1.335 | 0.072 | ||

| Mixed urban-rural (baseline—Big city) | 1.589 | 0.083 | ||

| Rural (baseline—Big city) | 1.839 | 0.085 |

Table 2 shows the amounts to which different considerations are taken into account when referring a patient. Patient preference (48.5%) and previous experience with specialists (59.1%) are reported to be the most important factors affecting GPs decision on referrals. There is, however, a high variation between countries on the importance of patients’ preference, ranging from 15% to 81%. Only a few countries stand out for using benchmark information (Czech Republic, Bulgaria and Romania) while this is virtually not-used in some others (Iceland and Norway). In some cases very practical reasons play a role. For instance, travel time which is mainly an issue in large geographically spread countries such as Australia and Canada.

Table 2. Answer to the question: In case of referral, to what extent do you take into account the following considerations?

| Country | Total no. of GPs | Always takes into account | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| patient’s preference where to go | travel distance for the patient | own previous experience with the specialist | comparative performance information on specialists | waiting time for the patient | costs for the patient | gatekeeping system (GK) QUALICOPC | ||||||||

| Austria | 177 | 85 | 48.0% | 97 | 54.8% | 137 | 77.4% | 37 | 20.9% | 20 | 11.3% | 68 | 38.4% | NO |

| Belgium | 384 | 283 | 73.7% | 103 | 26.8% | 301 | 78.4% | 100 | 26.0% | 60 | 15.6% | 64 | 16.7% | NO |

| Cyprus | 70 | 26 | 37.1% | 17 | 24.3% | 21 | 30.0% | 15 | 21.4% | 14 | 20.0% | 22 | 31.4% | NO |

| Czech Republic | 207 | 67 | 32.4% | 38 | 18.4% | 169 | 81.6% | 145 | 70.0% | 29 | 14.0% | 18 | 8.7% | NO |

| Denmark | 206 | 89 | 43.2% | 49 | 23.8% | 135 | 65.5% | 92 | 44.7% | 51 | 24.8% | 52 | 25.2% | NO |

| Germany | 234 | 103 | 44.0% | 131 | 56.0% | 172 | 73.5% | 33 | 14.1% | 31 | 13.2% | 31 | 13.2% | NO |

| Iceland | 74 | 32 | 43.2% | 18 | 24.3% | 44 | 59.5% | 3 | 4.1% | 6 | 8.1% | 12 | 16.2% | NO |

| Luxembourg | 73 | 54 | 74.0% | 16 | 21.9% | 59 | 80.8% | 27 | 37.0% | 10 | 13.7% | 5 | 6.8% | NO |

| Malta | 65 | 41 | 63.1% | 11 | 16.9% | 32 | 49.2% | 20 | 30.8% | 28 | 43.1% | 34 | 52.3% | NO |

| Poland | 192 | 104 | 54.2% | 87 | 45.3% | 92 | 47.9% | 60 | 31.3% | 102 | 53.1% | 91 | 47.4% | NO |

| Slovakia | 185 | 28 | 15.1% | 36 | 19.5% | 86 | 46.5% | 41 | 22.2% | 35 | 18.9% | 32 | 17.3% | NO |

| Switzerland | 189 | 103 | 54.5% | 81 | 42.9% | 167 | 88.4% | 34 | 18.0% | 30 | 15.9% | 27 | 14.3% | NO |

| Turkey | 297 | 64 | 21.5% | 99 | 33.3% | 107 | 36.0% | 40 | 13.5% | 73 | 24.6% | 132 | 44.4% | NO |

| FYR Macedonia | 122 | 30 | 24.6% | 33 | 27.0% | 66 | 54.1% | 24 | 19.7% | 45 | 36.9% | 58 | 47.5% | NO |

| Bulgaria | 199 | 104 | 52.3% | 61 | 30.7% | 136 | 68.3% | 112 | 56.3% | 48 | 24.1% | 81 | 40.7% | YES |

| Estonia | 129 | 71 | 55.0% | 36 | 27.9% | 75 | 58.1% | 11 | 8.5% | 38 | 29.5% | 35 | 27.1% | YES |

| Hungary | 205 | 81 | 39.5% | 89 | 43.4% | 118 | 57.6% | 48 | 23.4% | 81 | 39.5% | 98 | 47.8% | YES |

| Ireland | 162 | 106 | 65.4% | 71 | 43.8% | 108 | 66.7% | 31 | 19.1% | 70 | 43.2% | 81 | 50.0% | YES |

| Italy | 201 | 72 | 35.8% | 39 | 19.4% | 129 | 64.2% | 63 | 31.3% | 61 | 30.3% | 77 | 38.3% | YES |

| Latvia | 206 | 114 | 55.3% | 76 | 36.9% | 139 | 67.5% | 70 | 34.0% | 98 | 47.6% | 83 | 40.3% | YES |

| Lithuania | 216 | 79 | 36.6% | 19 | 8.8% | 68 | 31.5% | 36 | 16.7% | 40 | 18.5% | 19 | 8.8% | YES |

| Netherlands | 226 | 195 | 86.3% | 103 | 45.6% | 114 | 50.4% | 18 | 8.0% | 43 | 19.0% | 26 | 11.5% | YES |

| Norway | 195 | 67 | 34.4% | 48 | 24.6% | 84 | 43.1% | 13 | 6.7% | 58 | 29.7% | 56 | 28.7% | YES |

| Portugal | 205 | 80 | 39.0% | 77 | 37.6% | 72 | 35.1% | 55 | 26.8% | 81 | 39.5% | 103 | 50.2% | YES |

| Romania | 214 | 84 | 39.3% | 60 | 28.0% | 115 | 53.7% | 113 | 52.8% | 66 | 30.8% | 107 | 50.0% | YES |

| Slovenia | 203 | 41 | 20.2% | 36 | 17.7% | 80 | 39.4% | 37 | 18.2% | 65 | 32.0% | 32 | 15.8% | YES |

| Spain | 409 | 84 | 20.5% | 96 | 23.5% | 246 | 60.1% | 153 | 37.4% | 96 | 23.5% | 74 | 18.1% | YES |

| Sweden | 95 | 39 | 41.1% | 23 | 24.2% | 49 | 51.6% | 14 | 14.7% | 33 | 34.7% | 22 | 23.2% | YES |

| United Kingdom | 167 | 126 | 75.4% | 88 | 52.7% | 62 | 37.1% | 22 | 13.2% | 60 | 35.9% | 32 | 19.2% | YES |

| Australia | 149 | 121 | 81.2% | 97 | 65.1% | 123 | 82.6% | 41 | 27.5% | 57 | 38.3% | 82 | 55.0% | YES |

| Canada | 754 | 501 | 66.4% | 425 | 56.4% | 484 | 64.2% | 112 | 14.9% | 350 | 46.4% | 302 | 40.1% | YES |

| New Zealand | 162 | 116 | 71.6% | 65 | 40.1% | 92 | 56.8% | 22 | 13.6% | 62 | 38.3% | 108 | 66.7% | YES |

| total | 6572 | 3190 | 48.5% | 2325 | 35.4% | 3882 | 59.1% | 1642 | 25.0% | 1941 | 29.5% | 2064 | 31.4% | |

| total GK | 4097 | 2081 | 50.8% | 1509 | 36.8% | 2294 | 56.0% | 971 | 23.7% | 1407 | 34.3% | 1418 | 34.6% | |

| total non GK | 2475 | 1109 | 44.8% | 816 | 33.0% | 1588 | 64.2% | 671 | 27.1% | 534 | 21.6% | 646 | 26.1% | |

| Diff | 6.0% | 3.9% | -8.2% | -3.4% | 12.8% | 8.5% | ||||||||

| p | <0.005 | <0.005 | <0.005 | <0.005 | <0.005 | <0.005 | ||||||||

White denotes 0–25%, red denotes >25–50%, yellow denotes >50–75%, green denotes >75–100%.

GPs in countries with gatekeeping systems in place are more likely to always take into account patients’ preference, travel distance waiting time and costs, while the GPs from countries with no gatekeeping in place are more likely to consider their previous experience with a specialist and comparative performance information. The “p” value is <0.005 for all items.

Discussion

The first question of this study was whether countries vary to the extent GPs report shared decision-making (SDM), in deciding upon patients’ referral. Although GPs reported that SDM is the most common practice in 20 of the 32 countries, the results showed a strong variation between countries, ranging from over 90% to 35%. When decisions on referrals are not a shared decision, in most cases it is the GP who decides. Patients being the main decision-taker was reported rarely. Only one country, Poland, stands out for a particularly high percentage of decisions made by patients. This finding was explained by the Polish country coordinator based on the patients’ legal right of a “free choice”, i.e. GPs are not allowed to have the name of a specific specialist on the referral letter (personal communication with Prof. Dr. Adam Windak on June 8th, 2017).

To what extent does SDM in GPs referrals differ between gatekeeping and non-gate keeping systems? The paradoxical results of our analysis revealed that the answer to this question is not straightforward. On the one hand, we found a negative correlation between gatekeeper systems and SDM. Implying that GPs in gatekeeper systems in general, seem to be less likely to make shared decisions than GPs in a non-gatekeeping system. On the other hand, when looking in more detail at individual countries, it turns out that some countries deviate strongly from this general finding. The Netherlands, for instance, shows the highest score on SDM whereas this country has been one of the typical strong gatekeeper countries for a very long time. The same goes for the UK, a strong gatekeeper system, which shows over 80% of SDM. Other gatekeeper systems such as Spain and Denmark ended up on the other side of the distribution. This finding could potentially be related to variation between countries in for instance the level of patient trust in their GP, patient level characteristics such education level and health literacy, and beliefs about healthcare use.

We also investigated what factors GPs consider when referring to a medical specialist and how this differs between gatekeeping and non-gate keeping systems. Also, here our findings seem to nuance the negative relation between SDM and gatekeeping: it became apparent that GPs in gatekeeper systems more often take into account all kinds of patient interests, such as their preference, waiting time, costs, etc. compared to non-gatekeeping countries. In non-gatekeeping countries, the GPs’ own experiences with specialists and benchmarking information is more important. In general, it turns out that GPs apparently rely on their own experience, rather than e.g. benchmarking information.

The strength of our study lies in the large number of countries included and the statistically significant GP sample in each country and the data source similarity. Our study has also some limitations: 1) our findings are based only on GPs self-reported perception about how they do the referral, 2) no theoretical information on SDM was given to the GPs (question framed with 3 answer options: i) if they make the decision, ii) if the patient does or iii) if it is a shared decision), therefore, the results do not cover different understandings and culture around SDM, 3) we used the QUALICOPC classification of primary care systems: gatekeeping vs. non gatekeeping while other classifications (OECD) show there is also another cluster “in the middle” and a more nuanced approach to what constitutes gatekeeping can be taken and 4) the cultural bias between countries and languages and its effects on scoring “sometimes”.

Our study is one of the very few that can enrich the existing discussion (such as in BMJ) with empirical information. To our knowledge, this study is unique in the sense of providing a large international image, through the large number of countries included.

These results will aid clinicians having an overall view of the international practice. These mixed results may urge policymakers for 1) reconsidering the existing primary care mechanisms, 2) rethinking the use of ‘gatekeeper’ as a metaphor for something which is probably more a guide. The term gatekeeper seems to suggest that such GPs are mainly interested in protecting what is behind the gate and in preventing unwanted visitors from entering, rather than that they care about the preferences of people. This clearly is in sharp contrast with what this study showed. Likewise, our results will offer a debating ground for research articles for reflections like this. It seems a more nuanced and contextualized approach is needed to understand the relation between gatekeeping as a system design feature and its relation with and/or impact on shared decision making.

There is a need for further research. Our study is based on GPs’ perception, but it is also important to know how patients perceive the referral decision-making practice. Also, it is important to know what the main aspects are that GPs need to take into consideration when referring patients. International comparative research can help to understand the underlying phenomena but should be accompanied by contextualized knowledge on national situations to provide evidence for policy makers to redesign their health care system to optimize patient centeredness, efficiency and effectiveness alike.

Supporting information

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank their partners in the QUALICOPC project for their role throughout the study and their coordination of the data collection: NIVEL, the Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research, The Netherlands (W Boerma, P Groenewegen); StANNA, Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies, Italy (S Nuti, A M Murante, C Seghieri, M Vanieri); Department of Family Medicine and Primary Health Care, Ghent University, Belgium (J De Maeseneer, J Detollenaere, L Hanssens, S Willems); University of Ljubljana, Slovenia (D Rotar Pavlič, I Švab); Hochschule Fulda, University of Applied Sciences, Germany (S Greß, S Heinemann); RIVM, National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (T van Loenen). Authors would also like to thank the coordinators of the data collection in each country.

Data Availability

All data underlying the study are available without restrictions from the DANS repository at: https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-xau-tpzv.

Funding Statement

QUALICOPC was funded by the European Commission under the Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013; grant agreement 242141).

References

- 1.Roland M. and Nolte E. (2014). The future shape of primary care. British Journal of General Practice, 64(619), pp.63–64. doi: 10.3399/bjgp14X676960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kringos, D., Boerma, W., Hutchinson, A. and Saltman, R. (2017). Building primary care in a changing Europe (2015). [online] Euro.who.int. http://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/abstracts/building-primary-care-in-a-changing-europe-2015 [Accessed 22 Aug. 2017].

- 3.Brekke K., Nuscheler R. and Straume O. (2007). Gatekeeping in health care. Journal of Health Economics, 26(1), pp.149–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freund, D. and Neuschler, E. (1986). Overview of Medicaid capitation and case-management initiatives. Health Care Financing Reiew, [online] 7(Annual Supplement), pp.21–30. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4195090/pdf/hcfr-86-supp-021.pdf [Accessed 22 Aug. 2017]. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Loudon I. (2008). The principle of referral: the gatekeeping role of the GP. British Journal of General Practice, 58(547), pp.128–130. doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X277113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willems D. (2001). Balancing rationalities: gatekeeping in health care. Journal of Medical Ethics, 27(1), pp.25–29. doi: 10.1136/jme.27.1.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forrest C. (2003). Primary care in the United States: Primary care gatekeeping and referrals: effective filter or failed experiment?. BMJ, 326(7391), pp.692–695. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7391.692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cowling T, Soljak M, Bell D, Majeed A. Emergency hospital admissions via accident and emergency departments in England: time trend, conceptual framework and policy implications. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2014;107(11):432–438. doi: 10.1177/0141076814542669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garrido M., Zentner A. and Busse R. (2010). The effects of gatekeeping: A systematic review of the literature. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 29(1), pp.28–38 doi: 10.3109/02813432.2010.537015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franks P., Clancy C. and Nutting P. (1992). Gatekeeping Revisited—Protecting Patients from Overtreatment. New England Journal of Medicine, 327(6), pp.424–429. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199208063270613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vedsted P. and Olesen F. (2011). Are the serious problems in cancer survival partly rooted in gatekeeper principles? An ecologic study. British Journal of General Practice, 61(589), pp.508–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenfield G., Foley K. and Majeed A. (2016). Rethinking primary care’s gatekeeper role. BMJ, p.i4803 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Health Consumer Powerhouse (2016). Euro Health Consumer Index Report. Health Consumer Powerhouse Ltd., 2017. ISBN 978-91-980687-5-7

- 14.Kringos D., Boerma W., van der Zee J. and Groenewegen P. (2013). Europe’s Strong Primary Care Systems Are Linked To Better Population Health But Also To Higher Health Spending. Health Affairs, 32(4), pp.686–694. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schäfer W, Boerma W, Murate A, Sixma H, Schellevis F, Groenewegen P. Assessing the potential for improvement of primary care in 34 countries: a cross sectional survey. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2015;93(3):161–168. doi: 10.2471/BLT.14.140368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Britten N. (2000). Misunderstandings in prescribing decisions in general practice: qualitative study. BMJ, 320(7233), pp.484–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: What does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Social Science & Medicine. 1997;44(5):681–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Durand M, Carpenter L, Dolan H, Bravo P, Mann M, Bunn F et al. Do Interventions Designed to Support Shared Decision-Making Reduce Health Inequalities? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e94670 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shay L, Lafata J. Where Is the Evidence? A Systematic Review of Shared Decision Making and Patient Outcomes. Medical Decision Making. 2014;35(1):114–131. doi: 10.1177/0272989X14551638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kew K, Malik P, Aniruddhan K, Normansell R. Shared decision-making for people with asthma. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Groenewegen P., Greß S. and Schäfer W. (2016). General Practitioners’ Participation in a Large, Multicountry Combined General Practitioner-Patient Survey: Recruitment Procedures and Participation Rate. International Journal of Family Medicine, 2016, pp.1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schäfer W., Boerma W., Kringos D., De Maeseneer J., Greß S., Heinemann S., Rotar-Pavlic D., Seghieri C., Švab I., Van den Berg M., Vainieri M., Westert G., Willems S. and Groenewegen P. (2011). QUALICOPC, a multi-country study evaluating quality, costs and equity in primary care. BMC Family Practice, 12(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schäfer W., Boerma W., Kringos D., De Ryck E., Greß S., Murante A., Rotar-Pavlic D., Schellevis F., Seghieri C., Van den Berg M., Willems S. and Groenewegen P. (2013). Measures of quality, costs and equity inprimary health care: instruments developed to analyse and compare primary health carein 35 countries. Quality in Primary Care, [online] (21), pp.67–79. Available at: http://postprint.nivel.nl/PPpp4696.pdf [Accessed 22 Aug. 2017]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Health at a Glance: Europe 2016. Health at a Glance: Europe 2016. 2016.

- 25.Kringos D, Boerma W, Bourgueil Y, Cartier T, Hasvold T, Hutchinson A et al. The european primary care monitor: structure, process and outcome indicators. BMC Family Practice. 2010;11(1):81–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All data underlying the study are available without restrictions from the DANS repository at: https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-xau-tpzv.