Abstract

Wolbachia bacteria, vertically transmitted intracellular endosymbionts, are associated with two major host taxa in which they show strikingly different symbiotic modes. In some taxa of filarial nematodes, where Wolbachia are strictly obligately beneficial to the host, they show complete within- and among-species prevalence as well as co-phylogeny with their hosts. In arthropods, Wolbachia usually are parasitic; if beneficial effects occurs, they can be facultative or obligate, related to host reproduction. In arthropods, the prevalence of Wolbachia varies within and among taxa, and no co-speciation events are known. However, one arthropod species, the common bedbug Cimex lectularius was recently found to be dependent on the provision of biotin and riboflavin by Wolbachia, representing a unique case of Wolbachia providing nutritional and obligate benefits to an arthropod host, perhaps even in a mutualistic manner. Using the presence of presumably functional biotin gene copies, our study demonstrates that the obligate relationship is maintained at least in 10 out of 15 species of the genera Cimex and Paracimex. The remaining five species harboured Wolbachia as well, demonstrating the first known case of 100% prevalence of Wolbachia among higher arthropod taxa. Moreover, we show the predicted co-cladogenesis between Wolbachia and their bedbug hosts, also as the first described case of Wolbachia co-speciation in arthropods.

Introduction

Interspecific interactions that provide fitness benefits to all partners involved characterizes a large part of the world’s biodiversity1,2. One of its prime examples are symbiotic bacteria that are mutualistically connected with their metazoan hosts3. However, the degree of association and type of mutualism may vary among bacteria-metazoan species pairs and depend on environmental and community contexts2. Typical primary symbioses and true mutualisms are characterised by individual bacterial taxa that provide benefits to their host. Benefits to bacteria are rarely measured2 but may be implied if symbionts are restricted to specialised host cells and tissues, and are exclusively transmitted vertically. Secondary symbioses are characterized by more generic, not necessarily host-specific benefits and consequently, bacteria vary in prevalence across cells, tissues and populations of the host. Their effects on a given host may range from pathogenic to mutualistic, and they can be transmitted either vertically, horizontally, or both3.

The mode of symbiont transmission may profoundly affect patterns of phylogenetic co-variation between the symbionts and their hosts. In cases of vertical transmission, symbionts benefit from increased host fecundity, and therefore, selection typically favours mutualistic symbioses4. In contrast, horizontally transmitted symbionts show less dependence on their hosts and even often develop into parasites. Mutually beneficial symbiotic relationships are more likely to lead to congruent lineage divergence in populations of the two partner species than are non-beneficial relationships4,5, in which hosts usually show resistance to parasitic symbionts6. Over evolutionary time scales, the higher co-divergence in beneficial than non-beneficial interacting lineages results in co-speciation, displayed by congruent phylogenies of symbionts and hosts on higher taxonomic levels6. The depth and completeness of the co-cladogenesis pattern has, therefore, been used as a measure of the nature of a particular symbiotic relationship6. In contrast to mutualist relationships, only few cases of co-cladogenesis have been described from parasitic relationships, mainly from ectoparasites (e.g. Hafner’s classical gopher study7), but almost none have been reported from single cell parasites living inside host body or cells6.

Wolbachia bacteria are a prominent example of mainly vertically transmitted intracellular endosymbionts. The Wolbachia diversity has been classified into supergroups8, of which up to 17 has been described up to date9. Importantly, across their two major host groups, arthropods and filarial nematodes, Wolbachia vary in whether and how much they benefit their host10. In filarial nematodes, Wolbachia are exclusively mutualistic11 and are characterised as primary symbionts. For example, in different hosts, they are involved in the heme synthesis pathway12 or in ATP provision13, or are crucial for the host’s iron metabolism14 and riboflavin provision15. Nematode-associated Wolbachia are usually found in all individuals of a species16,17 and in all species within larger clades9. In these associations, Wolbachia seems to be exclusively vertically transmitted, which is regarded as a sign of host-provided benefits. As predicted, the mutualistic nature between Wolbachia and nematodes usually results in a tight co-speciation9,14,18.

By contrast, in arthropods, Wolbachia are typically parasitic but can provide benefits to hosts4. Wolbachia incidence is reported to be either around 66%19, or 40%20 among arthropod species. Infections often cause host phenotypes with distorted reproduction (reproductive phenotypes, or RPs)10,21. The most common RP is the induction of cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI), where infected females are only able to produce offspring with infected males, and in some cases only with males infected with the same Wolbachia strain10. Other RPs involve the killing or feminization of genetic males22 or the induction of parthenogenesis23. These RPs directly or indirectly increase the proportion of infected females and Wolbachia are, therefore, able to thrive without providing a fitness benefit to the host, despite vertical transmission and dependence on host fecundity.

Theory predicting that fitness benefits to the host may increase symbiont propagation has been confirmed empirically for Wolbachia, even while maintaining the parasitic mechanisms4. For example, the hosts of CI-inducing Wolbachia often display increased fecundity. This leads to a net benefit to the host, if Wolbachia prevail in the population. Following this path, in some arthropods Wolbachia have become an irreplaceable element of the host´s reproduction. For example, Wolbachia controls the apoptosis during oogenesis in Drosophila24 and in the wasp Asobara tabida25, and serves as a sex-determining factor through chromosome formation in the bean borer moth Ostrinia scapularis26. However, despite these sometimes strict dependencies, and unlike in nematodes, there is no evidence for co-cladogenesis of Wolbachia and arthropods20 with a single exception27, which is however ambiguous because horizontal transfer of Wolbachia could not have been ruled out. Indeed, horizontal transmission of Wolbachia among arthropods is frequent28–30.

Wolbachia in the common bedbug, Cimex lectularius, are a notable exception to both rules - because they do not cause RP and they are primary symbionts. Hosokawa et al.31 demonstrated that Wolbachia provide biotin and riboflavin, which are essential for bedbug development. In line with an obligatory nature of the relationship, there is a 100% prevalence of Wolbachia in Cimex lectularius populations32. The gene pathway responsible for the synthesis and provision of biotin to the bedbug has been horizontally transmitted from a co-infecting Cardinium or Rickettsia33. The loci in the closely related Cimex japonicus host contained two deletions relative to Cimex lectularius. The authors, Nikoh et al.33, therefore concluded that the biotin production in C. japonicus is dysfunctional, but suggested that its origin lies in a common ancestor of the two Cimex species. In contrast to the laterally acquired biotin genes, the pathway for riboflavin provided to the common bedbug is fully maintained and homologous across Wolbachia in all hosts studied so far34. However, the common bedbug is the only arthropod known to be provisioned by riboflavin produced by Wolbachia34.

Taken together, the characteristics of the bedbug-Wolbachia system are more similar to those of nematodes than other arthropods (primary vs. secondary symbiosis, generic benefits vs. mutualism, complete vs. partial prevalence). Here we test whether these characteristics are reflected in the predicted co-speciation of bedbugs and Wolbachia. If so, it is possible that related bedbug species use a similar type of Wolbachia mutualism based on vitamin provision. We predict that a) a 100% prevalence of Wolbachia within and among bedbug species, b) co-speciation of Wolbachia and their bedbug hosts and c) that across bedbug species, the presence and potential function of the biotin genes shows evidence for a beneficial relationship.

Material and Methods

Samples

Sampling was restricted to the subfamily Cimicinae and covers all close relatives of the human-associated C. lectularius, a lineage with a known Wolbachia status31,33. The samples comprise the bat-associated lineage of C. lectularius, the sister species C. emarginatus (S. Roth et al., unpublished), and representatives of the three remaining species groups35: C. pilosellus, C. pipistrelli, C. hemipterus, as well as two bird-associated species: C. hirundinis, C. vicarius (formerly classified as Oeciacus – see36). Three species of the closely related genus Paracimex are included as is another bird related Cimex sp. from Japan (Table S1). Specimens were morphologically identified using Usinger’s35 and Ueshima’s37 keys and compared against an available phylogenetic data base (S. Roth et al., unpublished).

Individuals of each species were collected from as many locations as possible, up to ten, in order to obtain a reliable estimate of intraspecific genetic diversity and a meaningful estimate of prevalence of Wolbachia in bedbug populations. For C. lectularius whose Wolbachia infection status is already known, we analysed one human-associated population and three bat-associated populations. A list of all samples used in this study can be found in Table S1.

DNA analyses

DNA was extracted from longitudinal halves of insect bodies in order to cover all insect tissues and account for all possible bacterial fauna. We extracted DNA for all samples using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen) and stored the DNA at −18 °C prior to use. To assess the infection status and reconstruct the phylogeny of the bedbug- specific Wolbachia strain, we studied two Wolbachia loci: the surface protein gene (WSP) and another protein-coding locus (HCPA). Both loci are widely used to characterize infection rate and describe phylogenetic relationships38. To track the beneficial relationship of Wolbachia to bedbug hosts, we chose two biotin loci: BioC and BioH. Each of these was previously found to contain a frameshift in Wolbachia of C. japonicus compared to the fully functional coding sequence in C. lectularius33, suggesting a loss of function in C. japonicus.

For WSP and HCPA loci, we used the universal primers designed for strain typing38. For each of the biotin loci, a pair of primers was designed to cover the whole coding region. For the bedbug phylogeny, we chose two mitochondrial loci, as mtDNA was shown to provide results congruent with a multilocus approach36 and exhibit the same inheritance mode as the Wolbachia infection. For species identification, we used the barcoding fragment of cytochrome oxidase subunit I (658 bp). For specimens chosen for the co-cladogenesis test, we used also a fragment of 16 S (386 bp). All primers used are listed in Table S2.

The target loci were amplified in 50 ul using GoTaq polymerase (Promega), recommended concentrations of other reagents and 2–4 ul of genomic DNA. The annealing temperature for each primer pair is given in Table S2. Purified PCR products were analyzed through a commercial sequencing service (Macrogen Inc. or GATC Biotech).

The HCPA sequences of samples 005 and 069 in C. pipistrelli and 120, 129 and 130 in C. hirundinis showed a secondary signal pointing to an infection by another Wolbachia strain (see Results). We validated by sequencing one sample per species using a newly designed primer HCPA-R2 (see Table S2) which specifically amplified only a single variant.

Phylogenetic analyses

The alignment of the sequence data was carried out using MAFFT39. The phylogenetic analyses were run in IqTree40 and MrBayes 3.041. Each analysis was carried out three times in order to assess convergence. The IqTree was used to infer Maximum Likelihood (ML) phylogenetic trees, using default settings, automatic model choice and 1000 bootstrap alignments. The Bayesian analyses were run using GTR (Generalised Time Reversible) model with gamma-distributed rate variation across sites and a proportion of invariable sites, both with default priors and priors set according to maximum model probability by sampling across GTR model space (lset nst = mixed rates = gamma). The MCMC chain was run in two simultaneous and independent runs for at least 2 million generations in order to achieve a standard deviation of split frequencies below 0.01. For the consensus tree, 10% of trees with unstable probability values were discarded as burn-in.

We chose 7 insect taxa with Wolbachia infections to serve as outgroup samples for phylogenetic analyses, according to a) similarity of the WPS sequence to C. lectularius associated Wolbachia and b) availability of HCPA sequence for the same sample.

The Wolbachia loci WSP and HCPA could have been affected by possible recombination between bacterial strains38. In order to reconstruct the Wolbachia phylogeny and test the co-cladogenesis with bedbug hosts, we used both loci as separate datasets as well as a concatenated dataset and compared the results. The two biotin loci are overlapping regions and were therefore analysed together as a partitioned dataset with independent model parameters for each gene. The two bedbug mitochondrial genes also do not recombine, therefore the same procedure was applied. Among the gene coding sequences, no gene alignment within the bedbugs using the primary sequence signal contained indels, however, the WSP alignment did when outgroups were included. From individuals that showed a secondary signals, we used only the sequence of the primary signal, after it was re-sequenced with the newly designed primer HCPA-R2 (see DNA analyses; Table S2).

In order to test for co-cladogenesis between Wolbachia and the host, we used the Icong index42, a topology-based method, and TreeMap 3.043 which encompasses both distance- and event-based algorithms. In addition, we used Tredist function in Phylip44 to assess the topological Robinson-Foulds distance45 of the mtDNA trees to the Wolbachia trees, comparing to distance to 1000 random trees generated by T-Rex46. For the Wolbachia trees, we used all unique combinations of WSP and HCPA sequences. The sequences of the secondary signal of the C. pipistrelli and C. hirundinis samples were not included (see Results). As the mtDNA variation within bedbug species was greater than that of Wolbachia sequences, we randomly assigned one of the corresponding mtDNA sequences to each unique Wolbachia sequence.

The included co-cladogenesis tests can use only binominal trees. Some of the Bayesian analysis produced polythomies at the terminal tree nodes; we therefore randomly deleted an appropriate number of taxa from the trees to be used. The final count of tree tips is given in Table 1. Using the Icong index, we counted the number of tree tips in the Maximum Agreement SubTree (MAST), and calculated the probability that the Wolbachia and bedbug trees were congruent by chance. The Treemap was used to test the significance of the number of co-divergence events by the Patristic Distance Correlation Test and the significance of the tree congruence was determined by comparing 1000 random Wolbachia trees, taking into account the timing of both bedbug and Wolbachia phylogenies, Priors were set as recommended by the preliminary mapping analysis.

Table 1.

Results of co-cladogenesis tests.

| Dataset for tree construction | WSP | HCPA | Concatenated | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phylogenetic method | Bayes | ML | Bayes | ML | Bayes | ML |

| No. of tree tips* | 14 | 18 | 11 | 14 | 16 | 20 |

| I cong results | ||||||

| Icong index | 1.842 | 1.783 | 1.667 | 1.474 | 1.893 | 1.536 |

| No. of tree tips in The Maximum Agreement SubTree | 10 | 11 | 8 | 8 | 11 | 10 |

| Significance (p-value) | 0.000020 | 0.000024 | 0.000311 | 0.002727 | 0.000007 | 0.000650 |

| Treemap results | ||||||

| Max. lineage codivergence events | 19 | 19 | 15 | 19 | 27 | 24 |

| No. of significant pairwise co-divergence events | 9 | 10 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 11 |

| Significance by randomizing (1000×) the parasite tree | 0.0080 | 0.0300 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Rating of Wolbachia tree among 1000 random trees based on Robinson-Foulds distance to the bedbug mtDNA tree | 1 | 1 | 1–2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

*Polytomies were collapsed, i.e. this number is higher by 1 than the number of co-divergence events in case of perfect co-speciation.

Samples identified as Paracimex borneensis and P. setosus appeared likely to be a single species based on sequence data. Since the taxonomy of the genus requires a thorough revision, we retained the identification based on morphology and geography, though the two samples are dealt with as a single species in Table 2.

Table 2.

Gene variation for species.

| Species | No. of locations (no. of specimens, if more than no. of locations) | mtDNA and Wolbachia variation | Biotin status | Synonymous and nonsynonymous variation in biotin | Deletions in biotin loci | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no. of mtDNA haplotypes (mean p-distance in COI) | WSP variation (no. of variants) | HCPA variation (no. of variants) | BioC | BioC | BioC | BioH | 91th bp of 2nd BioH variant | 475th bp of 2nd BioC variant | between 549–555th bp of 2nd BioC variant | close to BioC forward primer | ||||

| nonsyn | syn | nonsyn | syn | |||||||||||

| Paracimex setosus/borneensis x | 2 | 2 (0.000) | 2 | 0 | eroded | distant xx | eroded | 0.0905xx | 0.2714xx | na | na | na | na | |

| Paracimex cf. chaeturus | 1 (2) | 1 | 1 | 1 | distant | eroded | 0.0400 | 0.1497 | eroded | na | ? | ? | ? | |

| Cimex adjunctus | 9 | 8 (0.011) | 2 | 2 | functional | functional | 0.0037 | 0.0050 | 0.0066 | 0.0060 | na | na | na | na |

| Cimex antennatus | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | functional | functional | 0.0037xxx | 0.0000xxx | 0.0044 | 0.0060 | na | na | na | na |

| Cimex brevis | 10 | 5 (0.004) | 1 | 1 | functional | functional | 0.0056 | 0,0000 | 0.0044xxx | 0.0308xxx | na | na | na | na |

| Cimex latipennis | 2 | 2 (0.016) | 1 | 1 | functional | functional | 0.0093 | 0.0151 | 0.0022 | 0.0246 | na | na | na | na |

| Cimex hemipterus | 7 (8) | 2 (0.004) | 2 | 1 | distant | distant | 0.0404 | 0.0952 | 0.0296 | 0.0319 | all samples | all samples | no deletion | no deletion |

| Cimex lectularius | 4 | 4 (0.013) | 2 | 1 | functional | functional | 0.0037 | 0.0050 | 0.0022 | 0.0060 | na | na | na | na |

| Cimex emarginatus | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | functional | functional | 0.0037 | 0.0050 | 0.0044 | 0.0060 | na | na | na | na |

| Cimex pipistrelli | 13 | 10 (0.018) | 2 | 2 | functional | functional | 0.0056 | 0.0050 | 0.0088 | 0,0000 | all samples | all samples | no deletion | all samples |

| Cimex japonicus | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | functional | functional | 0.0056 | 0.0050 | 0.0066 | 0,0000 | all samples | all samples | no deletion | all samples |

| Cimex hirundinis | 5 | 2 (0.003) | 2 | 1 | functional | functional | 0.0056 | 0.0050 | 0.0088 | 0.0060 | no deletion | all samples | all samples | no deletion |

| Cimex vicarius | 2 (3) | 3 (0.002) | 2 | 1 | functional | functional | ? | at least 3 deletions at different positions | ||||||

| Cimex sp. Japan | 3 (4) | 1 | 1 | 1 | functional | functional | 0.0056 | 0.0050 | 0.0066 | 0.0000 | all samples | all samples | no deletion | no deletion |

xThe two Paracimex species delimited according to37 appeared to be a single species according to mtDNA and Wolbachia sequences.

xxbased on 186 bp fragment amplified by BioC primers.

xxxvalue incl. C. adjunctus sample N1. The Wolbachia of the sample N1 clustered with C. brevis based on WSP and HCPA loci, and is identical to C. brevis in BioH sequence, but to C. antennatus in BioC sequence. In BioC C. brevis and C. antennatus differ only in a single nucleotide. Therefore the identity of BioC of sample N1 to C. antennatus may likely be a convergence.

eroded = contained deletions or stop codons, therefore it was not possible to use the same method for computing the syn and nonsyn mutations.

na = secondary signal not present.

bold = biotin loci concluded to be non-functional.

Test of function of biotin loci

We used codon structure integrity of BioC and BioH sequences, and their relative divergence from a common ancestor, to infer the functionality of biotin production of Wolbachia. Paracimex cf. chaeturus and all samples within the clade consisting of Cimex hemipterus, C. pipistrelli group and all bird-related Cimex species provided sequences with two or more overlaying signals. These sequences however clearly represented the same variants differing in length, i.e. deletions were present in some. Most samples within species showed the full-length variant to be clearly dominant and the secondary signal to be of a consistent peak height. Therefore, we could easily separate the full-length sequence from the dominant signal as only two locations were available and the secondary signal was strong, except for in C. vicarius. As an additional safeguard, we manually reviewed the sequence by chromatogram inspection using CodonCode Aligner 6.0.2. The secondary signal was synchronous with the full-length variant until the deletion in the direction of reading. Since all samples were sequenced from both ends of each locus, for each part of the sequence a synchronous and asynchronous double signal was available. The synchronous signal served to detect the variable sites, as well as to correct for within-species variation. The asynchronous signal then served to assess the correct nucleotide at each of the variants. Only two sites in C. pipistrelli, three in Cimex sp. Japan and six in C. japonicus remained ambiguous in the full-length variants.

In order to test whether Wolbachia biotin loci are functional and underlie the symbiotic relationship in bedbug species other than C. lectularius31, we compared all sequences with the sequence of a presumed common ancestor of the sampled species. We reconstructed the ancestral sequences for the biotin loci based on sequences that contained no frame shift or no stop codons, using Mega 7.047. As the node representing the common ancestor we naturally chose the trichotomy between clades consisting of a) C. pilosellus group, b) C. lectularius group and c) a clade consisting of C. pipistrelli group, C. hemipterus and the bird-associated Cimex species (Cimex sp., C. vicarius and C. hirundinis). These three clades correspond to traditional systematics of the genus Cimex and consistently show monophylies in phylogenetic studies, but the relationships among them remain unresolved (Figs 1 and S136, S. Roth et al. unpublished). The divergence in synonymous and non-synonymous changes was computed in PAML 4.848 using the method by Yang & Nielsen49.

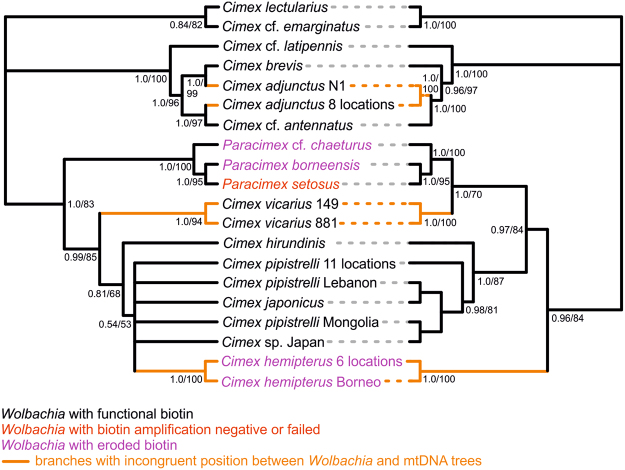

Figure 1.

Cladograms based on mtDNA (right) and Wolbachia WSP and HCPA loci (left). Bayes posterior probability values are given at each node. For congruence test resuls see Table 1. All unique combinations of sequences of Wolbachia were used, along with mtDNA of corresponding samples. Labels after species name refer to collection site (Table S1). Highlighted are the different positions of a) Cimex adjunctus sample N1, b) C. vicarius and c) C. hemipterus.

Data availability

The DNA sequences of both bedbugs and Wolbachia used in the study are available at GenBank under codes provided in Table S1.

Results

Wolbachia prevalence

All 68 individuals of all 15 bedbug species tested were Wolbachia-positive (Figs 1 and S1, Table 2). Except for five samples (2/13 from C. pipistrelli, 3/5 from C. hirundinis; see next paragraph), both WSP and HCPA genes showed unambiguous sequences of a single Wolbachia strain present. In those five samples, only HCPA showed a double signal, According to the consistence of the peak heights, this double signal suggests the presence of two Wolbachia strains. The dominant signal belonged to the same Wolbachia strain that was found in other bedbug species. The variation of WSP and HCPA loci of this strain within bedbug species was either zero or very low (Table 2). The low diversity of WSP among the bedbug species allowed for visual inspection of alignment and let us conclude that no codon mismatch or recombination across the WSP sequence had occurred.

The HCPA sequences reconstructed from the secondary signal of the five samples of C. hirundinis and C. pipistrelli pointed to a co-infection by another strain. The sequence and the relative strength of the signal was consistent across specimens of each species, all coming from different geographic locations. It always represented Wolbachia infections belonging to supergroups other than supergroup F according to a clustering with the outgroups (Fig. S1; for sample codes see Table S1). We therefore have solid reasons to believe that the secondary signal represented a single less abundant Wolbachia strain in each Cimex species. Wolbachia supergroups other than F have not been previously found to provide benefits to bedbugs and were, therefore, not tested for co-phylogeny with bedbugs.

Co-cladogenesis

Each dataset (Wolbachia WSP, HCPA, WSP + HCPA, Wolbachia biotin loci, bedbug mtDNA) produced the same topology and very similar posterior probability or bootstrap values across across all runs and priors, either in Bayesian or ML analyses (Figs 1, S1 and S2). The trees based on a particular dataset produced by Bayesian analyses were sometimes less resolved than the ML ones, but otherwise no conflicts in topology were observed. The only topology differences between trees based on different Wolbachia datasets were the varying positions of Cimex hemipterus and C. vicarius.

The bedbug and Wolbachia trees were clearly congruent (Fig. 1). Both Treemap and Icong co-cladogenesis tests unambiguously supported a close congruence of bedbug and Wolbachia phylogenies (Table 1). Among 1000 random trees, the Robinson-Foulds distance of the Wolbachia to the mtDNA trees was always lowest using either Bayesian or ML trees datasets based on any of the Wolbachia datasets.

Across all the six of bedbug mtDNA tree with the Wolbachia trees comparisons (three Wolbachia datasets, two phylogenetic methods), positions of only three taxa differed. Two of them, however, represented unstable topologies across different Wolbachia trees as well (see Discussion).

Biotin function

The Wolbachia biotin loci were successfully amplified in all but two specimens. In one P. borneensis specimen (C94) the BioH primers failed and in P. setosus (C9) neither locus was amplified despite repeated trials. It is not possible to determine whether the failure to amplify was caused by poor DNA quality, the absence of the biotin loci or primer mismatch due to sequence divergence. However, amplification of the HCPA locus using general primers failed as well in these two specimens.

Wolbachia in all samples within the clade consisting of Cimex hemipterus, C. pipistrelli group and the bird-related Cimex species showed at least one additional variant of the biotin loci. The secondary signal was present in Paracimex cf. chaeturus but only visible when the BioC reverse primer was used for sequencing. These variants contained deletions and the pattern of the distribution of the deletions along the genes was largely consistent across species (Table 2). The two deletions in biotin genes found in C. japonicus in a previous study33 were found in the secondary signal of biotin in our samples as well, along with two other deletions.

Biotin sequences drawn from the dominant signal showed low divergence from the presumed ancestral sequence and were similar among most of the bedbug species (Table 2, Fig. S2). No changes in codon structure were detected. In all Paracimex species and in C. hemipterus, BioC sequences contained frameshifts in all variants detected. The divergence from the common ancestor of the sequences drawn from the dominant signal was one order of magnitude higher than in the rest of the species.

Discussion

Our study revealed two patterns of Wolbachia infection in bedbugs that proved to be unique to arthropods and that have previously been thought to be typical for, and restricted to, nematodes. First, as predicted, we showed a 100% prevalence of Wolbachia within and among the sampled bedbug species. This contrasts with reports from other arthropods showing infection rates that are typically either below 10%, or above 90% within species19,20,50,51, although infections up to 100% have been observed even within presumably parasitic relationships52,53. A high prevalence is predicted in Wolbachia-nematode relationships, where Wolbachia are usually present in all individuals16,17 and where all genera or larger monophyletic clades are infected9.

Secondly, we show, by various methods, the predicted very close co-cladogenesis between bedbugs and Wolbachia, which is a unique finding among arthropods, but is the norm in filarial nematodes and their Wolbachia symbionts9,18. One potential case of co-speciation has been reported in arthropods, namely that between Wolbachia and three Nasonia wasp species27 although horizontal transfer of Wolbachia was not ruled out. Our results show significant congruence between Wolbachia and the bedbug phylogenies in 15 species, regardless of whether any of the Wolbachia loci or the concatenated dataset were used. Three cases of incongruence between bedbug and Wolbachia phylogenies were observed in each analysis (Fig. 1). While such incongruence may be attributable to limited molecular information used in our study, all three cases are also consistent with alternative hypotheses. In one case, the position of Cimex vicarius varied between the Wolbachia and bedbug phylogenies, as well as among different Wolbachia trees. The position of C. vicarius has been very unstable even in previous multilocus phylogeny reconstructions36, possibly due to a conflict between nuclear and mitochondrial molecular data. Wolbachia molecular information is therefore not fully comparable. In the second case, the position of C. hemipterus varied among Wolbachia trees as well. Non-functional biotin provision by Wolbachia and consequently less stringent symbiosis with a host and a different evolutionary divergence are attributable in this case. The third case likely represents a transfer of Wolbachia from C. brevis to the population of C. adjunctus (sample N1, Fig. 1), a possibility facilitated by the fact that the two species are phylogenetically closely related36 and live in geographic vicinity35.

Both results, the complete prevalence and the co-cladogenesis with the host, are predicted4 if, as has previously been found, the bedbug-Wolbachia relationship is based on mutualistic nutritional provision31. The fact that both predictions were upheld simultaneously may indicate that both phenomena are related and may be part of a syndrome characterising the transition from detrimental to beneficial Wolbachia. Two other characters are also correlated with the type of symbiosis and we propose they are part of a syndrome. Nematode-Wolbachia relationships are strictly vertically inherited, whereas horizontal transmission between arthropod species or populations are common5. Finally, nematode individuals or species are infected by single strains, while infections by multiple strains are common in arthropod species. However, despite the striking parallel between the bedbug and the nematode-associated obligate nutrient provision, co-cladogenesis was not entirely congruent between bedbugs and Wolbachia. Five samples, corresponding to two species (C. hirundinis and C. pipistrelli) showed evidence of an infection with two phylogenetically distant Wolbachia strains (Fig. S1). It is currently not clear whether both strains are involved in nutrition provision or represent a case of competition between two strains that would be resolved over time (with the predicted outcome of the mutualistic strain outcompeting the non-mutualistic one4;). The occurrence of two strains also suggests that horizontal transfer of Wolbachia between bedbug species may not be impossible although it is not currently clear how a horizontal transfer might have happened between C. adjunctus and C. brevis (Fig. 1). Sterile interspecific matings have been observed in several bedbug species, including between C. adjunctus and C. brevis35, though sexual transmission of Wolbachia has to our knowledge not previously been observed.

It may also be important to note that while strict co-speciation is considered ubiquitous for Wolbachia-nematode associations14,18, the supergroup F, to which the bedbug-associated Wolbachia belongs31, shows considerable breakdowns of co-speciation patterns with the nematode hosts17,54. In such context, the co-cladogenesis of Wolbachia with bedbugs that we showed may represent a case of the tightest co-phylogeny recorded for the Wolbachia supergroup F.

We found no evidence of an erosion of the protein coding structure in the Wolbachia biotin loci, including in the Wolbachia of C. japonicus. Dissimilar to the study of Nikoh et al.33, we conclude that the Wolbachia biotin synthesis is still in function in most Cimex species (except C. hemipterus, see below). The difference between the two studies may have arisen because of intraspecific variation of Wolbachia in C. japonicus or, alternatively, because our study may have used primers with different specificity than Nikoh et al.33 had.

We observed additional variants of the biotin loci in a monophylum consisting of all bird-associated species, the C. hemipterus and C. pipistrelli species group (i.e. including C. japonicus, see Table 2). These biotin variants contained frameshifts similar to those found in C. japonicus by Nikoh et al.33 and did not represent functional genes. Since functional variants were also present in most of these hosts, the presence of the deleterious ones does not suggest an arrest in biotin provision by Wolbachia to the bedbugs. The deleterious variants are unlikely to originate from co-infecting Wolbachia strains, because WSP and HCPA loci showed no evidence of a secondary infection in the respective specimens, except in the previously mentioned samples of C. hirundinis and C. pipistrelli. However, it is noteworthy that the positions of the deletions in the biotin sequence was very similar among species (Table 2), strongly suggesting a common origin of the deleterious variants within the species clade, though the actual location of the variants remains unknown.

We found deleterious and non-functional sequences exclusively in Cimex hemipterus and in two Paracimex species. The difference between these two groups and the rest of Cimex is further supported by the length of branches of these taxa on the HCPA and WSP trees (Fig. S1), compared to the length of branches in other Cimex species with functional biotin. While most bedbug species in our analysis use biotin provision by Wolbachia, the Wolbachia symbiosis in C. hemipterus and Paracimex spp. is likely evolutionarily different, perhaps dependent on other resources provisioned by Wolbachia, such as riboflavin. This idea may be tested by experimental using Wolbachia manipulations in C. hemipterus and Paracimex.

Conclusions

Regardless of the discussed details, our data provide clear evidence that the syndrome of transition from a host-detrimental to a host-beneficial relationship has evolved in convergence in both bedbugs and filarial nematodes. Both bedbugs and filarial nematode show 100% Wolbachia prevalence and strict co-speciation of Wolbachia and the host taxa. This is exceptional among arthropods, and bedbugs therefore offer a valuable example of evolution of symbiotic relationships. Given the recently proposed possibilities that nematodes that are harmful to humans may be controlled with antibiotics targeting their Wolbachia, it would be interesting to explore whether such a possibility exists in bedbugs, too.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful for all the collectors that helped gathering the bedbug samples (for names see Table S1). We also thank Dr. Nusha Keyghobadi (Western University, Canada) for English language typographical and grammatical editing. The research was funded by an internal grant of University of Life Sciences, Faculty of Environmental Sciences, no 20164246 IGA FŽP (Ondřej Balvín), and by Meltzer Research Fund (Steffen Roth). Klaus Reinhardt was supported by the Zukunftskonzept of the TU Dresden, funded by the Excellence Initiative of the DFG.

Author Contributions

Ondřej Balvín and Steffen Roth carried out the molecular lab work and participated in data analysis. All authors participated in the collection of material, in the design of the study and in writing the manuscript. All authors gave final approval for publication.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-25545-y.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bronstein JL. Our Current Understanding of Mutualism. Q. Rev. Biol. 1994;69:31–51. doi: 10.1086/418432. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mushegian AA, Ebert D. Rethinking “mutualism” in diverse host-symbiont communities. BioEssays. 2016;38:100–108. doi: 10.1002/bies.201500074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moran NA, Baumann P. Bacterial endosymbionts in animals. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2000;3:270–275. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(00)00088-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zug R, Hammerstein P. Bad guys turned nice? A critical assessment of Wolbachia mutualisms in arthropod hosts: Wolbachia mutualisms in arthropods. Biol. Rev. 2015;90:89–111. doi: 10.1111/brv.12098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zug R, Koehncke A, Hammerstein P. Epidemiology in evolutionary time: the case of Wolbachia horizontal transmission between arthropod host species. J. Evol. Biol. 2012;25:2149–2160. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2012.02601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Vienne DM, et al. Cospeciation vs host-shift speciation: methods for testing, evidence from natural associations and relation to coevolution. New Phytol. 2013;198:347–385. doi: 10.1111/nph.12150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hafner MS, Nadler SA. Cospeciation in Host-Parasite Assemblages: Comparative Analysis of Rates of Evolution and Timing of Cospeciation Events. Syst. Zool. 1990;39:192–204. doi: 10.2307/2992181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Werren JH, Zhang W, Li RG. Evolution and phylogeny of Wolbachia: reproductive parasites of arthropods. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1995;261:55. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1995.0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lefoulon E, et al. Breakdown of coevolution between symbiotic bacteria Wolbachia and their filarial hosts. PeerJ. 2016;4:e1840. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Werren JH. Biology of wolbachia. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1997;42:587–609. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.42.1.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fenn K, Blaxter M. Are filarial nematode Wolbachia obligate mutualist symbionts? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2004;19:163–166. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strübing U, Lucius R, Hoerauf A, Pfarr KM. Mitochondrial genes for heme-dependent respiratory chain complexes are up-regulated after depletion of Wolbachia from filarial nematodes. Int. J. Parasitol. 2010;40:1193–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Darby AC, et al. Analysis of gene expression from the Wolbachia genome of a filarial nematode supports both metabolic and defensive roles within the symbiosis. Genome Res. 2012;22:2467–2477. doi: 10.1101/gr.138420.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown AMV, et al. Genomic evidence for plant-parasitic nematodes as the earliest Wolbachia hosts. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:34955. doi: 10.1038/srep34955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foster J, et al. The Wolbachia Genome of Brugia malayi: Endosymbiont Evolution within a Human Pathogenic Nematode. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor M, Bandi C, Hoerauf A. Wolbachia bacterial endosymbionts of filarial nematodes. Adv. Parasitol. 2005;60:245–284. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(05)60004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferri E, et al. New Insights into the Evolution of Wolbachia Infections in Filarial Nematodes Inferred from a Large Range of Screened Species. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e20843. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Comandatore F, et al. Phylogenomics and analysis of shared genes suggest a single transition to mutualism in Wolbachia of nematodes. Genome Biol. Evol. 2013;5:1668–1674. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evt125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hilgenboecker K, Hammerstein P, Schlattmann P, Telschow A, Werren JH. How many species are infected with Wolbachia? – a statistical analysis of current data: Wolbachia infection rates. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2008;281:215–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01110.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zug R, Hammerstein P. Still a Host of Hosts for Wolbachia: Analysis of Recent Data Suggests That 40% of Terrestrial Arthropod Species Are Infected. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e38544. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Werren JH, Baldo L, Clark ME. Wolbachia: master manipulators of invertebrate biology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008;6:741–751. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valette V, et al. Multi-Infections of Feminizing Wolbachia Strains in Natural Populations of the Terrestrial Isopod Armadillidium Vulgare. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e82633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boivin T, et al. Epidemiology of asexuality induced by the endosymbiotic Wolbachia across phytophagous wasp species: host plant specialization matters. Mol. Ecol. 2014;23:2362–2375. doi: 10.1111/mec.12737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fast EM, et al. Wolbachia enhance Drosophila stem cell proliferation and target the germline stem cell niche. Science. 2011;334:990–992. doi: 10.1126/science.1209609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dedeine F, et al. Removing symbiotic Wolbachia bacteria specifically inhibits oogenesis in a parasitic wasp. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2001;98:6247–6252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101304298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kageyama D, Traut W. Opposite sex–specific effects of Wolbachia and interference with the sex determination of its host Ostrinia scapulalis. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2004;271:251–258. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raychoudhury R, Baldo L, Oliveira DCSG, Werren JH. Modes of acquisition of Wolbachia: horizontal transfer, hybrid introgression, and codivergence in the Nansonia species complex. Evolution. 2009;63:165–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heath BD, Butcher RD, Whitfield WG, Hubbard SF. Horizontal transfer of Wolbachia between phylogenetically distant insect species by a naturally occurring mechanism. Curr. Biol. 1999;9:313–316. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(99)80139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cordaux R, Michel-Salzat A, Bouchon D. Wolbachia infection in crustaceans: novel hosts and potential routes for horizontal transmission. J. Evol. Biol. 2001;14:237–243. doi: 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2001.00279.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stahlhut JK, et al. The mushroom habitat as an ecological arena for global exchange of Wolbachia. Mol. Ecol. 2010;19:1940–1952. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hosokawa T, Koga R, Kikuchi Y, Meng X-Y, Fukatsu T. Wolbachia as a bacteriocyte-associated nutritional mutualist. PNAS. 2010;107:769–774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911476107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sakamoto JM, Rasgon JL. Geographic distribution of Wolbachia infections in Cimex lectularius (Heteroptera: Cimicidae) J. Med. Entomol. 2006;43:696–700. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/43.4.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nikoh N, et al. Evolutionary origin of insect-Wolbachia nutritional mutualism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014;111:10257–10262. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409284111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moriyama M, Nikoh N, Hosokawa T, Fukatsu T. Riboflavin Provisioning Underlies Wolbachia’s Fitness Contribution to Its Insect Host. mBio. 2015;6:e01732–15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01732-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Usinger, R. L. Monograph of Cimicidae. (Entomological Society of America, 1966).

- 36.Balvín O, Roth S, Vilímová J. Molecular evidence places the swallow bug genus Oeciacus Stål within the bat and bed bug genus Cimex Linnaeus (Heteroptera: Cimicidae) Syst. Entomol. 2015;40:652–665. doi: 10.1111/syen.12127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ueshima ND. host relationships and speciation of the genus Paracimex (Cimicidae: Hemiptera) Mushi. 1968;42:15–27. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baldo L, et al. Multilocus Sequence Typing System for the Endosymbiont Wolbachia pipientis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;72:7098–7110. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00731-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katoh K, Asimenos G, Toh H. Multiple Alignment of DNA Sequences with MAFFT. Methods Mol. Biol. 2009;537:39–64. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-251-9_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trifinopoulos J, Nguyen L-T, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. W-IQ-TREE: a fast online phylogenetic tool for maximum likelihood analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W232–W235. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MR BAYES 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Vienne DM, Giraud T, Martin OC. A congruence index for testing topological similarity between trees. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:3119–3124. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Charleston MA, Robertson DL, Sanderson M. Preferential Host Switching by Primate Lentiviruses Can Account for Phylogenetic Similarity with the Primate Phylogeny. Syst. Biol. 2002;51:528–535. doi: 10.1080/10635150290069940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baum BR. PHYLIP: Phylogeny Inference Package. Version 3.2. Joel Felsenstein. Q. Rev. Biol. 1989;64:539–541. doi: 10.1086/416571. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robinson, D. F. & Foulds, L. R. Comparison of phylogenetic trees. Math. Biosci. 53, 131–147

- 46.Boc A, Diallo AB, Makarenkov V. T-REX: a web server for inferring, validating and visualizing phylogenetic trees and networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W573–W579. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015;33:1870–4. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang Z. PAML 4: a program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007;24:1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang Z, Nielsen R. Estimating synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution rates under realistic evolutionary models. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2000;17:32–43. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tagami Y, Miura K. Distribution and prevalence of Wolbachia in Japanese populations of Lepidoptera. Insect Mol. Biol. 2004;13:359–364. doi: 10.1111/j.0962-1075.2004.00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahmed, M. Z., Araujo-Jnr, E. V., Welch, J. J. & Kawahara, A. Y. Wolbachia in butterflies and moths: geographic structure in infection frequency. Front. Zool. 12 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Riegler M, Stauffer C. Wolbachia infections and superinfections in cytoplasmically incompatible populations of the European cherry fruit fly Rhagoletis cerasi (Diptera, Tephritidae) Mol. Ecol. 2002;11:2425–2434. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schuler H, et al. The hitchhiker’s guide to Europe: the infection dynamics of an ongoing Wolbachia invasion and mitochondrial selective sweep in Rhagoletis cerasi. Mol. Ecol. 2016;25:1595–1609. doi: 10.1111/mec.13571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lefoulon E, et al. A new type F Wolbachia from Splendidofilariinae (Onchocercidae) supports the recent emergence of this supergroup. Int. J. Parasitol. 2012;42:1025–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The DNA sequences of both bedbugs and Wolbachia used in the study are available at GenBank under codes provided in Table S1.