Abstract

Spinel based transition metal oxide – FeV2O4 is applied as a novel anode for sodium-ion battery. The electrochemical tests indicate that FeV2O4 is generally controlled by pseudo-capacitive process. Using cost-effective and eco-friendly aqueous based binders, Sodium-Carboxymethylcellulose/Styrene butadiene rubber, a highly stable capacity of ~97 mAh∙g−1 is obtained after 200 cycles. This is attributed to the strong hydrogen bonding of carboxyl and hydroxyl groups indicating superior binding with the active material and current collector which is confirmed by the ex-situ cross-section images of the electrode. Meanwhile, only ~27 mAh∙g−1 is provided by the electrode using poly(vinylidene difluoride) due to severe detachment of the electrode material from the Cu foil after 200 cycles. The obtained results provide an insight into the possible applications of FeV2O4 as an anode material and the use of water-based binders to obtain highly stable electrochemical tests for sodium-ion battery.

Introduction

The commercialization of Lithium ion batteries (LIBs) by Sony in 1991, paved the way for the development of portable devices1. However, the excessive costs and geographical constraints of lithium resources, made it impossible for LIBs to sustain and meet the growing demands of rechargeable batteries2–12. As a result, alternative battery systems are being explored. One of the most notable systems is the Sodium ion batteries (SIBs) owing to its abundance, low cost and availability8,11,13–15. Na atom is larger and heavier than Li atom (1.02 Å vs. 0.76 Å)16,17; therefore, the gravimetric and volumetric energy densities of SIBs are generally lower than LIBs. Nevertheless, energy density would not pose a great issue in terms of large-scale energy storage systems9,12,18. Numerous progresses on SIBs greatly focus on cathode materials, and although there is a growing number of studies on anode materials, most studies are limited to hard carbons19–21. Hard carbon, a non-graphitic carbonaceous compound, is given the highest considerations due to its large interlayer distance disorder structure3,22. Pyrolized glucose derived hard carbon prepared by Stevens and Dahn delivered a reversible sodium capacity of 300 mAh∙g−1 22,23 However, non-graphitic carbonaceous compounds suffer from high irreversible capacity loss and low capacity retention22. Na-alloying type anodes, such as Sn, Sb, P, Ge and In have also been reported to deliver high reversible capacities22,24,25. Howbeit, these materials suffer from large volume change during electrochemical tests which results in electrode pulverization, loss of contact with the current collector, and subsequent capacity fading24,26.

Transition metal oxides (TMOs) have been greatly studied on LIBs due to their high theoretical capacities (>600 mAh·g−1) which is obtained through conversion reaction of oxides with Li12,21,27–30. The reduction of metal ions during the lithiation process leads to higher capacities than the commercial graphite anode (in LIBs)21. Furthermore, in conversion based anode materials, the anode materials are converted and new phases are expected to form13. TMOs can store energy through the conversion of the metals (reduction and oxidation), as well as alloying and de-alloying, which provides high reversibility. Ternary TMOs are known to provide higher electronic conductivities than simple metal oxides31. The first conversion anode material for SIBs was introduced by Alcantara’s group32. When they discharged the battery from 4.1 to 0.0 V, it delivered an initial capacity ~350 mAh·g−1 and subsequently decreased to ~250 mAh·g−1 at 0.2 V after four cycles. It is generally lower than that of LIBs, but in comparison to hard and soft carbon, NiCo2O4 still provided a higher capacity.

Vanadium metal takes multiform valence states which can provide series of transition metal vanadium-based compounds (AxVyBz) (A=Co, Cr, Fe, Zn, Mn, Mg, Bi, etc., B=O, S or Se)33. These vanadium-based compounds have been widely used as electrodes for rechargeable batteries for more than 30 years34. In LIB systems, numerous vanadium containing compounds have been studied such as, ZnV2O435,36, CoV2O637, CuV2O638, Cu2.33V4O1139, FeVO433,40 and so forth. However, several of these compounds have not been yet applied to Na-ion battery systems. It is known that at 1.0 V, it can achieve multi-electron transfer due to its multivalent properties, indicating a possibility of higher capacity delivery than Ti-based anodes34,41. Iron-based materials are known to provide high theoretical capacity due to its multi-valence states (Fe0, Fe2+, and Fe3+) which provide redox pairs of Fe0/Fe2+, Fe0/Fe3+ and Fe2+/Fe3+. Furthermore, iron is a highly abundant element with a comparable price to commercial activated carbon, hence making it economically viable for industrial-scale applications42. With these advantages provided by iron and vanadium oxides, Fe-V-O compound is expected to exhibit notable electrochemical performance for SIBs applications. Based on these ideas, spinel oxide FeV2O4 was prepared and its electrochemical performance was analyzed in this study. The magnetic, orbital and structure phase transitions of FeV2O443–45 have been widely investigated but it has not been employed as an anode material for both Li and Na-ion battery systems.

The effects of different binders were also carried out in this study. Various studies have used Poly(vinylidene difluoride) (PVdF) as binder for both LIBs and SIBs6,13,30,46. In LIBs, PVdF is known to have good electrochemical stability, strong binding ability to both the electrode and current collector, and could absorb electrolyte that facilitates Li+ transport to the surface of the active materials46–52. However, it requires a toxic and expensive solvent (N-methyl-I-1-pyrrolidone, NMP) as its dispersing medium. Furthermore, PVdF is wettable in non-aqueous liquid electrolyte which could lead to the detachment of the electrode from the current collector, thus increasing contact resistance46. As for its application in SIBs, it has been reported that PVdF suffers from defluorination during sodium intercalation because of the lack of passivation in Na-ion cell53.

Na-carboxylmethylcellulose (CMC), a linear polymeric derivative of cellulose with different levels of carboxylmethyl substitution, is one of the aqueous binders that is considered to replace PVdF47. Another known water-based binder is the Styrene butadiene rubber (SBR) which possesses higher flexibility, stronger binder force, and better heat resistance than PVdF54. Zhang et al. reported that the synergistic effect of CMC/SBR offered enhanced rate capability and increased cycling stability for ZnFe2O4 anode for LIBs. Furthermore, the cross-sectional SEM images of their electrodes revealed the poor contact of the PVdF based electrode with the current collector after cycling. Also, Wang and colleagues claimed improved electrochemical performance of their MoS2 using CMC/SBR in comparison to PVdF54. It is believed that the improved electrochemical properties is due to the high tolerance of water-based polymer binders (such as CMC/SBR) against internal mechanical stress caused by volume expansion47. Based on these, this study focuses on the (i) preparation of a novel anode material FeV2O4 and (ii) preliminary analyses of its electrochemical properties for Na – battery systems with the incorporation of non-aqueous (PVdF) and aqueous (CMC/SBR) binders.

Results and Discussion

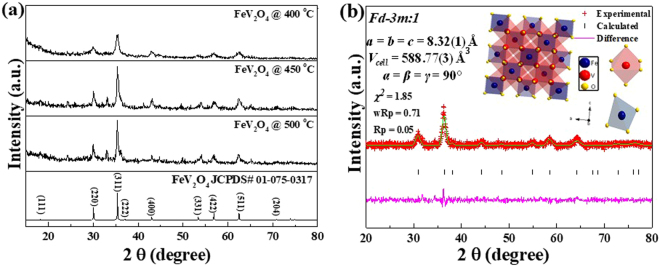

The XRD profiles of FeV2O4 with different calcination temperatures (400–500 °C) are illustrated in Fig. 1(a). It was evident that the spinel structure of FeV2O4 are formed when the samples are calcined at 400 °C and all the diffraction peaks are well indexed to the standard diffraction pattern (JCPDS # 01-075-0317). Meanwhile, when the temperature was raised to 450–500 °C, impurity peaks situated at ~25°, 33° appeared which are attributable to V2O3 impurity (JCPDS # 00-001-1293). As a result, the sample calcined at 400 °C was used in the electrochemical tests. Rietveld refinement of FVO is shown in Fig. 1(b). FeV2O4 crystallizes in a face-centered cubic spinel structure with space group Fd m:1. The lattice parameters were determined to be a = 8.32(1) Å, b = 8.32(1) Å, c = 8.32(1) Å and α = β = γ = 90° with a cell volume of 588.77(3) Å3. The error bar of the lattice parameters and cell volume are depicted in Supplementary Fig. S1. The calculated average of the lattice parameters is 8.338 ± 0.027 Å with an average cell volume of 588.563 ± 0.291Å3, respectively. Lastly, the calculated crystallite size of FeV2O4 at 400 °C is 88.461 Å. The crystal structure and the corresponding coordination environments of Fe2+ and V3+ ions are displayed in the insets of Fig. 1(b). Iron cations are positioned in the tetrahedral (FeO4) 8a sites, while vanadium ions are situated in the octahedral (VO6) 16d sites and a network or grid of corner-sharing tetrahedra with cubic-closed pack oxygen anions reside in the 32e sites55. To further prove the crystallinity of FeV2O4 post heat-treated at 400 °C, a slower scan rate of 0.02 °∙s−1 was used to test its XRD. Based on Fig. S2, all peaks were indexed to the standard XRD patterns and no impurity was detected.

Figure 1.

(a) XRD profiles of FeV2O4 calcined at different temperatures under H2/N2 atmosphere and (b) Rietveld refinement. Insets: crystal structure of FeV2O4 with the FeO4 and VO6 polyhedra.

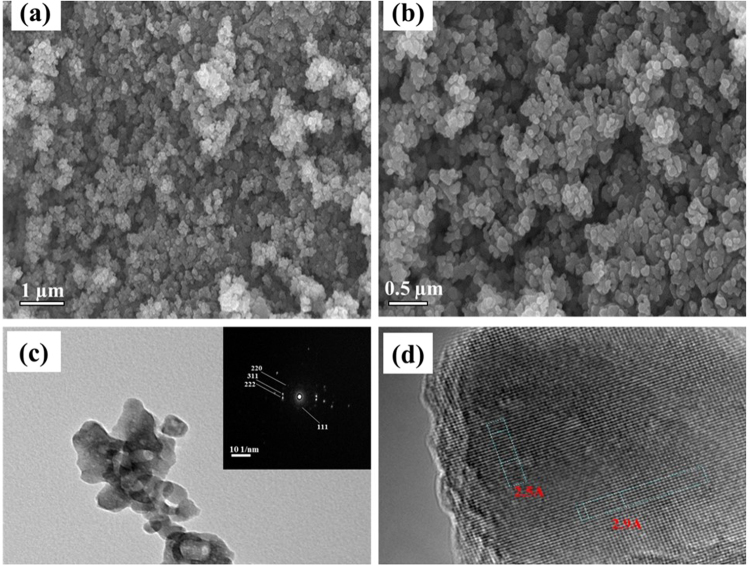

The morphologies and elemental compositions of FeV2O4 are depicted in Fig. 2(a–d). It was evident from the SEM images in Fig. 2(a,b) that FeV2O4 are agglomerated with irregular shapes. This is further confirmed by the TEM image in Fig. 2(c). The SAED in the inset of Fig. 2(c) confirms the crystallinity of FeV2O4 as it agrees with the characteristic diffraction peaks. HRTEM image of FeV2O4 in Fig. 2(d) show the lattice fringes of 2.9 Å and 2.5 Å which correspond to the (220) and (311) planes of FeV2O4, respectively. The elemental composition of FeV2O4 was confirmed using EDS technique as shown in Fig. S2a. The characterization was executed four times at different sites to confirm even distributions of Fe, V and O. In Fig. S2b the bar graph of the atomic % of the elements are displayed with the average compositions, corresponding standard deviations of the elements and errror bars. Based on the gathered data, the calculated At.%AVE composition (Fe:V:O) = 14.35:27.3:58.35 is close to the stoichiometric ratio of FeV2O4 demonstrating uniform distribution of the elements. In addition, the elemental mapping in Fig. S3 further validates the composition and even distribution of the elements.

Figure 2.

(a,b) SEM, (c) TEM and inset: SAED, and (d) HRTEM images of FeV2O4.

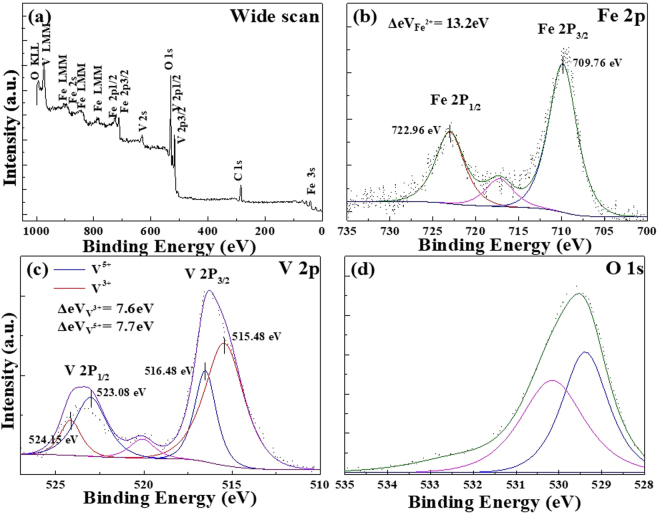

The wide scan in Fig. 3(a) shows all the possible elements presented in the sample primarily: Iron (Fe), Vanadium (V) and Oxygen (O). Meanwhile Fig. 3(b–d) illustrates the deconvoluted narrow scans of Fe, V and O to confirm the oxidation states of each elements. Figure 3(b) reveal the existence of Fe2+ (FeO) as indicated by the Fe 2p3/2 and Fe 2p1/2 peaks at 709.76 eV and 722.96 eV, respectively. The pink line located at 716.5 eV was due to the satellite peak of Fe2+ and the spin-orbit splitting between 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 were both calculated to be 13.2 eV which concurs with the standard value of 13.1 eV. Meanwhile, both V3+ and V5+ are found to co-exist as presented in Fig. 3(c). The peaks corresponding to V 2p3/2 and V 2p1/2 are situated at 515.48 eV and 523.08 eV, respectively for V3+. On the other hand, V5+ ions have peaks situated at 516.48 eV for V 2p3/2 and 524.184 eV for V 2p1/2. The calculated spin-orbit splitting for V 2p3/2 and V 2p1/2 for both V3+ and V5+ are 7.6 eV and 7.7 eV, respectively which are in agreement with the standard value of 7.64 eV4. The pink line at ~ 520 eV is a satellite peak that could be attributed to the existence of both V3+/5+. The ratio of V3+:V5+ was calculated to be 3:2. The presence of V5+ could be attributed to slight the surface oxidation56. Lastly, Fig. 3d displays the XPS of O1s. The deconvoluted peaks at 530.12 eV and 529.22 eV were attributed to the metal oxides of FeO, V2O3 and V2O5.

Figure 3.

XPS of FeV2O4: (a) Wide scan and narrow scans of (b) Fe, (c) V, and (c) O.

Due to the surface oxidation of the sample, X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) spectrum of V K-edge were determined to probe the local oxidation of Vanadium. Supplementary Fig. S4 compares the K-edge XANES profile of V in FeV2O4 with standard metallic vanadium and vanadium oxides. The spectra in Fig. S4a display pre-edge, low-energy shoulder and edge energy absorption peaks. The pre-edge peaks correspond to the coordination environment of V in which the peak intensity is inversely proportional to the coordination geometries57. It is assigned as the forbidden transition 1s → 3d followed by a low-energy shoulder peak which is attributed to the 1s → 4p. Finally, the strong peak corresponds to the dipole-allowed transition 1s → 4p57. It can be observed that V2O5 and VO2 have more defined and intense peaks compared to V2O3 and FeV2O4. According to Nabavi and colleagues58, V5+ in V2O5 has both VO4 and VO5 coordination states whereas the V in standard V2O3 and FeV2O4 both occupy an octahedral site (VO6). Unlike V2O5, both standard V2O3 and FeV2O4 do not have a shoulder peak prior to the edge-energy absorption peak. In Fig. S4b, it can be clearly discerned that the edge energies (1s → 4p) of different vanadium oxides shift to higher energies. This energy shift is known as chemical shift which follows the Kunzl’s and is linearly proportional to the valence of the absorbing vanadium atoms57. The inset in Fig. S4b shows the comparison of the pre-edge and edge energy peaks of FeV2O4 with the standard V2O3 and V2O5. Although the pre-edge peaks of V2O3 and V2O5 are both located at the same peak, the intensity of V2O5 is higher because of its VO4 and VO5 polyhedra. On the other hand, the first energy edge peaks of FeV2O4 and V2O3 are close to each other. Moreover, V K-edge spectra profiles of FeV2O4 and V2O3 are qualitatively similar, thus confirming the successful synthesis of FeV2O4 with V3+ oxidation state.

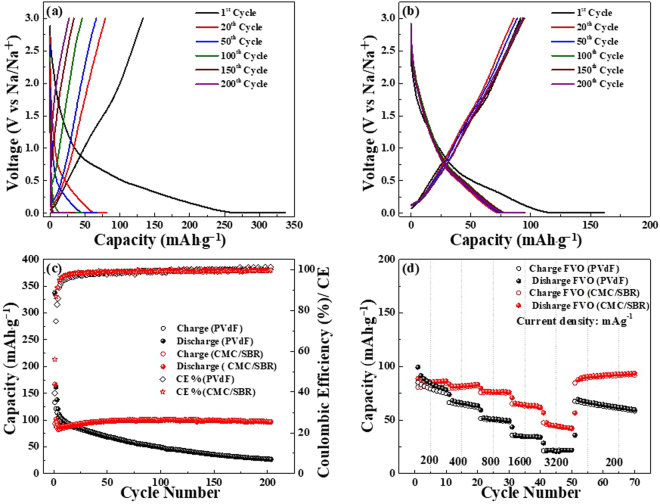

The electrochemical evaluation of Na/NaClO4(EC:DEC)/FeV2O4 are evaluated and exhibited in Fig. 4. The galvanostatic charge/discharge of FeV2O4 using PVdF and CMC/SBR (FVO-PVdf and FVO-CMC/SBR) as binders are represented in Fig. 4(a,b). Although the intital charge/discharge profiles (at 100 mA·g−1) of the two electrodes look similar, the capacity of FVO-PVdF electrode was two times higher than FVO-CMC/SBR (333 mAh∙g−1 vs. 167 mAh∙g−1). However, the coulombic efficiencies were 40% and 56% for FVO-PVdF and FVO-CMC/SBR, respectively. The irreversible capacity was due to the formation of solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) layer between the anode and the electrolyte which is caused by the decomposition of the solvent in the electrolyte14. After prolonged cycling at 200 mA·g−1, the charge/discharge profiles revealed very poor stability and high voltage offset for PVdF. This was ascribed to the large polarization and mechanical energy dissipation caused by induced stress during the rapid charge and discharge process59. On the other hand, the profiles of the FVO-CMC/SBR electrode appear to overlap even after 200 cycles denoting good stability and low polarization.

Figure 4.

Electrochemical performance of FeV2O4 electrodes. Galvanostatic charge/discharge profiles of (a) FVO-PVdF and (b) FVO-CMC/SBR electrodes at potential window of 0.01–3.0 V. Comparisons of the (c) cycle life and (d) rate capability tests of FVO-PVdF and FVO-CMC/SBR electrodes.

Cycle tests with corresponding coulombic efficencies of FVO-PVdF and FVO-CMC/SBR are illustrated in Fig. 4(c). The first three cycles for formation were tested at 100 mAh∙g−1 while the rest were tested at 200 mA∙g−1. Evidently, the first few cycles of FVO-PVdF was higher than that of FVO-CMC/SBR however, prolonged cycling resulted in rapid capacity fading and lower coulombic efficiency. After 100 cycles, it was only able to retain about 39% of its capacity upon running at 200 mA∙g−1 with a coulombic efficiency of 99%. Further cycling to 200 cycles caused the battery to die eventually. It is theorized that that rapid charge/discharge caused the PVdF electrode to suffer from cracks, large volume expansion and loss of contact from the current collector. Conversely, the FVO-CMC/SBR depicts a stable cycle test upto 200 cycles. As mentioned above, the inital capacities of FVO-PVdF are higher than FVO-CMC/SBR, however, as the test continued, it was revealed that FVO-CMC/SBR delivered a more stable capacity.

It was noticeable that there was a gradual increase in the capacity, which is very common in TMOs and has been widely observed in LIBs applications. The capacity increase was due to the formation of reversible pseudo-capacitive polymeric/gel film like that is believed to be responsible for the extra uptake of Li+ on the SEI layer60,61. Since LIBs and SIBs are governed by the same rocking chair mechanism, the electrochemical properties of TMOs in SIBs are also affected by this phenomena. Moreover, since the morphology of the FeV2O4 is highly agglomerated, there are inactive sites in the electrode that didn’t form an initial reaction in the sodiation and desodiation process. With continued cycle test, nano-sized particles are believed to have formed which eventually became exposed and provided more active sites during the sodiation and desodiation process. After 200 cycles, FVO-CMC/SBR obtained a reversible capacity of ~97 mAh∙g−1 with a coulombic efficiency of 99%. At this stage, CMC/SBR was able to overcome the large volume expansion and maintained a good contact with the Cu foil. Even though FVO-CMC/SBR provided a highly stable capacity, it is obvious that the delivered capacities were very low. The theoretical capacity of FeV2O4 is believed to be ~967 mAh∙g−1 (1 C) considering 8 mol of Na+ during full conversion process. However, at 100 mA∙g−1 only 1.4 mol of Na+. This huge difference could be attributed to the follwing factors: large ionic radius of Na atom, thicker SEI layer (effect of electrolyte, which is not a scope of this research), and few active sites for Na+ to induce full conversion of the Fe and V metals. In order to achieve improved electrochemical properties of FeV2O4, futher developments should be done such as carbon coating to buffer volume expansion, metallic doping to increase kinetics, controlling its morphology, or providing a layered structure. And while these methods could provide increased capacity, the stability of the electrode is hugely affected by the binder.

Aside from the cycle tests, rate capability of the two electrodes were also studied and is shown in Fig. 4(d). FVO-PVdF electrode has average discharge capacities of 85, 66, 52, 36, and 22 mAh∙g−1 at current densities of 200, 400, 800, 1600, and 3200 mA∙g−1, respectively. When cycled back to 200 mA∙g−1, it was able to recover an average capacity of 63 mAh∙g−1, which is 25% less of the initial discharge cycle. Meanwhile, FVO-CMC/SBR electrode delivered an average discharge capacities of 86, 82, 77, 65, and 46 at 200, 400, 800, 1600, and 3200 mA∙g−1, respectively. Upon cycling back to 200 mA∙g−1, it recovered an average of 90 mAh∙g−1 which is higher than the former average at 200 mA∙g−1. These results are all indicative of the better stability that CMC/SBR offer over prolonged cycle test.

As mentioned above, it was inferred that FVO-PVdF electrode suffer from huge cracks on the surface and detachment from the Cu foil. To have further insight on the binding abilities of the different binders, ex-situ SEM analyses of the electrodes were performed. Supplementary Fig. S5 show the surface and cross-section morphologies of FVO-PVdF. The pristine electrode in Fig. S5a displayed uniform coating, however, it appears to have some shallow cracks which could have been formed upon drying the electrode. After the initial charge/discharge cycle (Fig. S5b), huge and deep cracks are seen on the surface and the distances between the cracks range from 1.72–7.29 µm. However, the effect of continued cycle, caused the particles to become interconnected and the cracks on the surface were lessened. Furthermore, the cross-section images were also studied as shown in Fig. S5(d–g). The pristine electrode has an average thickness (Dave) of 11.32 µm. After one cycle, expansion is evident, and the Dave increased to 15.88 µm and the electrode was evidently detached from the current collector resulting in increased contact resistance. Further sodiation and desodiation, caused the electrode material to be severely detached from the Cu foil as shown in the low magnification image of the electrode in Fig. S5f. Also, cracks at the bottom of the electrode were present. The average thickness after 200 cycles was calculated to be 34.14 µm (Fig. S5g), indicating huge expansion by ~201%. The inevitable huge volume expansion, detachment from the current collector and cracks are attributable to the weak hydrogen bonding of fluorine in PVdF (Fig. S7a) with the active material and current collector54,62.

In comparison, supplementary Fig. S6 displays the ex-situ surface and cross-section morphologies of FVO-CMC/SBR. In Fig. S6a, the pristine electrode does not have obvious cracks on the surface and shows uniform coating. The carboxyl chains in CMC (Fig. S7b) provides an effective surface charge on the FeV2O4 and Super-P particles, therefore stabilizing the particles dispersion through an electrostatic double-layer repulsion mechanism54,63. After one cycle, cracks were also present on the surface as shown in Fig. S6b. However, comparing it to the cracks on FVO-PVdF electrode, the cracks appear to be shallow and short. In fact, the gaps were measured to be from 0.74–2.79 µm which are extremely smaller than that of FVO-PVdF electrode. Similarly, the surface of the electrode in Fig. S6c, appear to become denser and the particles are more connected as a result of the SEI formation on the surface and the swelling of the binder54. Some of the initial small pores as seen in Fig. S6a, were almost gone and the surface appeared to be smoother and more compact. In contrast to the FVO-PVdF after 200 cycles, FVO-CMC/SBR has no evident cracks on the surface. The cross-sections of the electrodes were also analyzed. The average thickness of the pristine electrode in Fig. S6d is measured to be 11.93 µm and after one charge and discharge cycle, (Fig. S6e), the Dave increased to 14.04 µm. Fig. S6(f) shows the cross-section of the electrode cycled up to 200 cycles with Dave = 22.40 µm, denoting 88% expansion. Huge cracks were also present, but the electrode material was still strongly attached to the Cu foil. Nevertheless, it is 2x lower than the volume expansion provided by PVdF. The relatively stronger adhesion of CMC/SBR on the current collector could be ascribed to the strong hydrogen bond of the carboxyl and hydroxyl groups in CMC with the FeV2O4, Super-P and Cu foil54,62. Zhang et al. noted that CMC makes the electrode extremely stiff and brittle when used alone as a binder. It easily forms cracks and can make the electrode slide-off the current collector. Combining CMC with SBR lessens the brittleness of the electrode. In comparison to PVdF, CMC/SBR provide smaller Young’s modulus, larger maximum elongation, and improved adhesion to the current collector54,64.

The plateaus in the galvanostatic charge/discharge profiles of FVO-CMC/SBR which correspond to the reduction and oxidation of Fe and V are not very distinct which is very common for other TMOs applied for both LIBs and SIBs12,15,65–67. Cyclic voltammetry test (CV) provides confirmation of the conversion of the metals. The CV profile of FVO-CMC/SBR is shown in Supplementary Fig. S8. It displays CV curves at a constant scan rate of 0.1 mV·s−1. During the first cycle, there are two broad reduction peaks located at ~0.3–0.6 V and ~1.0–1.4 V, and a narrow and broad oxidation peaks at 0.05 V and ~1.25–1.75 V, respectively. The oxidation peak at 0.05 V is attributed to Super-P. In the subsequent cycles, the reduction peak at ~0.8–1.4 V disappeared, which implies that it is due to the formation of SEI layer. The broad peak at ~0.3–0.6 V shifted to ~0.6–0.8 V in the 2nd-5th cycles denoting irreversible electrochemical reaction in the initial discharge cycle68. Meanwhile, the oxidation peaks at ~1.25–1.75 V is still present in the succeeding cycles. It can be clearly seen that the CV profiles for the subsequent cycles are overlapping each other showing excellent reversibility.

It is speculated that the reduction and oxidation peaks for both Fe and V coincides with each other. In the works of Gao et al. on FeO/C69, they suggested that the reduction of of Fe2+ → Fe0 occurs at ~0.7 V and a broad oxidation peak at ~ 1.5–2.0 V that corresponds to the oxidation of Fe0 → Fe2+. Jiang and colleagues studied V2O3 nanowires for LIB and they found out that the reduction of V3+ → V0 is situated at 0.68 V and the oxidation occurs in two step process (V0 → V3+) located at 1.25 and 2.62 V70. The reported oxidation and reduction peaks for Fe in LIBs agree with the obtained reduction peak of Fe2+ → Fe0 at ~0.6–0.8 V, and oxidation peak of Fe0 → Fe2+ at ~1.25–1.75 V. However, taking into consideration the strong V-O bonding34, obtaining metallic V will be difficult. Hence, the low capacity of FeV2O4. As mentioned earlier, the CV of Li-V2O3 has a broad reduction peak (0.68 V) and two oxidation peaks (1.25 and 2.62 V). Conversely, in the CV of Na-FeV2O4, only one oxidation peak is observed. Ergo, the broad reduction peak at ~0.6–0.8 V corresponds to V3+ → V2+ and the broad oxidation peak ca. 1.25–1.75 V denotes V2+ → V3+. The CV profile of SIBs are broader than LIBs due to the larger size, heavier mass and slower mobility of Na+ than Li+66.

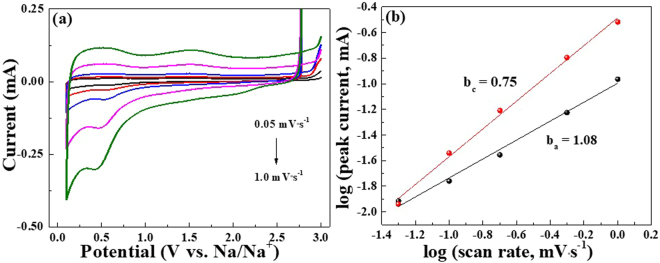

In order to understand the capacitive behavior of FeV2O4, CV measurements at different scan rates were performed (Fig. 5(a)). As expected, the CV curves tend to deviate from its original position as the scan rate is increased which is due to the increase in polarization and ohmic resistance. The relationship between the current and the scan rate was determined using the equaiton14:

| 1 |

where the i is the measured current and v is the scan rate. The b-value can be calculated using the slope of log(v) vs. log(i). If the b-value is close to 0.5, the electrochemical behavior is controlled by diffusion process, on the other hand, if the b-value is close to 1.0, it is based on capacitive process. Figure 5(b) illustrates the linear relationship of log(v)-log(i) using different scan rates and based on the fitting, the obtained cathodic and anodic b-value were calculated to 0.75 and 1.08, respectively. These values confirm the electrochemical behavior of FeV2O4 was mainly due to pseudo-capacitive process, hence a higly stable cycle test is obtained14,71–73.

Figure 5.

(a) CV curves of FVO-CMC/SBR with different scan rates from 0.05 to 1.0 mV·s−1 from 0.01–3.0 V. (b) Graph of log(v) vs. log(i).

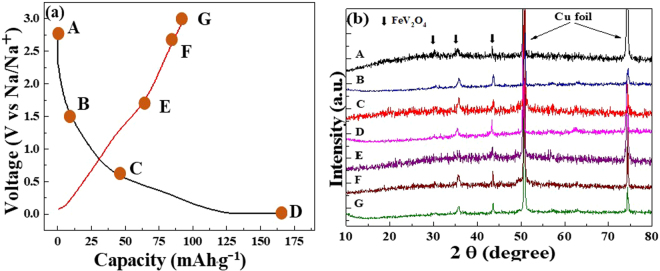

To get a better understanding of the mechanism that governs conversion materials such as FeV2O4 in SIBs, it is necessary to perform ex-situ analyses. For TMOs, it is essential to recognize the conversion reaction that transpires during sodiation and desodiation or if there have been occurance of any phase transformations. It was mentioned that in full conversion, FVO could achieve ~967 mAh∙g−1, however based on the gathered data, full conversion of the metals were not obtained. Consequently, the reaction mechanism is as follows:

| 2 |

To further verify whether full conversion of the metals or any phase transformations have transpired during sodiation and desodiaion, ex-situ XRD characterizations of FVO-CMC/SBR electrodes were implemented. Figure 6b shows the six electrodes which were charged and discharged at certain voltages based on the CV profiles and galvanostatic charge/discharge profiles (Fig. 6(a)). The fresh electrode has the crystalline peaks of the spinel compound. When discharged and charged to different voltages, it is obvious that the XRD peaks indexed to FeV2O4 are still present indicating incomplete conversion reaction. It implies that incomplete conversion reaction occurred during sodiation and desodiation resulting in low capacities. This phenomenon is comparable to the works of Zhou et al.67 on NiFe2O4 and Mai et al.74 on NaAlTi3O8 in which their in-situ XRD did not indicate any conversion of the metals. However, in Fig. 6b, there is a subtle shift of the XRD peaks to the lower angle when discharged to 0.01 V. This occurance demonstrates lattice expansion due to the insertion of Na+ upon sodiation. Subsequently, when charged to 1.5–3.0 V, the XRD peaks indexed to FeV2O4 shifted to the right indicating release of Na+ upon desodiation74. It is also speculated that the thick SEI layer could have played a huge part on this. Hence, only few active sites were exposed to Na+ during sodiation.

Figure 6.

(a) Galvanostatic charge/discharge profile of FVO-CMC/SBR electrodes with orange marks corresponding to different depths of charge and discharge and (b) Ex-situ XRD profiles as indicated by the orange marks (A = pristine; B = D1.5 V, C = D0.5 V, D = D0.01 V and E = C1.5 V, F = C2.8 V and G = C3.0 V).

The conversion reaction mechanism of metal oxides are not yet fully understood in Na-ion systems. Further characterizations of the electrodes using in-situ XRD sychrotron or in-situ Neutron diffraction analyses must be employed since these equipment are more highly sensitive to light elements such as Na and O74. Nevertheless, FeV2O4 electrode has a very high stability and reversibility which is ascribed to its pseudo-capacitive properties with the aid of the exceptional properties of CMC and SBR.

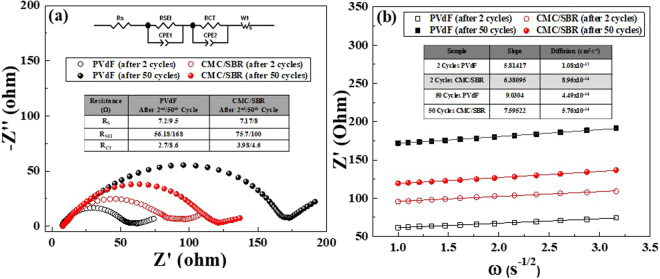

Using Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS), the internal resistance in the coin cell were determined and calculated. Figure 7(a) shows a typical EIS profile which is comprised of semicircles and a straight sloping line at a lower frequency region75. The semicircle found in the highest frequency is denoted as RS and is generally known as the electrolyte resistance. The semicircle in the middle frequency is ascribed to RCT and RSEI which correspond to charge transfer resistance and SEI film resistance, respectively. The sloping line, W or Warburg impedance located at the lower frequency represents the Na+ diffusion. The insets in Fig. 7(a) display the equivalent circuit and the calculated RS, RSEI, and RCT of FVO-PVDF and -CMC/SBR after 2 and 50 cycles. The calculated RS, RSEI, and RCT of FVO-PVdF electrde were 7.2, 56.18 and 2.7 Ω, after 2 cycles and increased to 9.5, 168, and 8.6, respectively after 50 cycles. On the other hand, FVO-CMC/SBR provided RS, RSEI, and RCT of 7.17, 75.7 and 3.98 Ω, respectively after 2 cycles. The resistance increased to 8, 100 and 4.6 Ω for RS, RSEI, and RCT, respectively after the 50th discharge cycle. The large RSEI for both electrodes verify the poor initial coulombic efficiencies and incomplete conversion of the metals which is highly affected by the electrolyte. Comparing the two electrodes, the initial RSEI and RCT of FVO-PVdF is lower than FVO-CMC/SBR which is in agreement with the initial higher capacity delivered by FVO-PVdF electrode. However, after 50 cycles of (dis)charge cycles, the internal resistance of FVO-PVdF became siginificantly higher compared to FVO-CMC/SBR. These stipulate that PVdF failed to overcome the loss of contact between the active material and Cu foil and the large volume expansion that has arose during the sodiation and desodiation process hence, the large internal resistance. Moreover, it further proves that the fluorine atoms in PVdF only form weak hydrogen bonds with the active material and current collector54. The kinetics of the diffusion species were also investigated and calculated using the formula76:

| 3 |

where R is the ideal gas constant, T is temperature in Kelvin, F is the Faraday’s constant, A is the electrode surface, CLi is the concentration of Li in the electrolyte, and DLi is the diffusion coefficient By calculating the slope (σ), from EIS, DLi were calculated to be 8.965 × 10−14 and 5.762 × 10−14 cm2∙s−1 for FVO-CMC/SBR and 1.08 × 10−13 and 4.49 × 10−14 cm2∙s−1 for FVO-PVdF after the 2nd and 50th cycle, respectively. Initially, the Na+ diffusion for FVO-PVdF is slightly faster than FVO-CMC/SBR. After 50 cycles, there was a considerable decrease on the diffusion of Na+ ions in FVO-PVdF electrode. On the other hand, a very subtle decrease in the diffusion kinetics of FVO-CMC/SBR was observed. In fact, the increase in the internal resistance of the cell and the decrease in kinetics are very minimal even after 50 cycles. These agree with the trend in the cycle life tests in which after 50 cycles (FVO-CMC/SBR), it was able to retain 100 mAh∙g−1 with a very high stability suggesting that FeV2O4 could be viable conversion anode material for Na-ion battery. Although the obtained capacities were relatively low, it is believed that modifying its morphology and framework, doping with metals, and coating with carbon could highly improve its overall performance.

Figure 7.

(a) EIS and (b) diffusion coefficient calculations of FVO-PVdF and -CMC/SBR electrodes.

Conclusions

Spinel oxide-FeV2O4 was employed as a novel anode material for sodium-ion battery. It was verified that its electrochemical behavior is mainly governed by pseudo-capacitive process. Incomplete conversion reaction was discovered in the ex-situ XRD. This could be due to the presence of inactive sites in the electrode, formation of thick SEI layer since no additives were used in the electrolyte and the strong V-O bonding. By using CMC and SBR as binders, a highly stable cycle test was achieved compared to PVdF. This was ascribed to the strong hydrogen bonds formed between the carboxyl/hydroxyl groups in CMC with the active material and Cu foil. Moreover, SBR provided better adhesion of the slurry to the Cu foil. Although FVO-CMC/SBR only provided a reversible capacity of ~97 mAh∙g−1 at 200 mA∙g−1 for 200 cycles, this study provided preliminary investigations on the application of FeV2O4 as a conversion based anode material for sodium-ion battery.

Methods

Materials synthesis

Pure-phase FeV2O4 were obtained through simple solvothermal synthesis. 1.2120 g of Iron nitrate nonahydrate (Fe(NO3)2·9H2O), 0.7019 g of Ammonium vanadate, (NH4VO3) were mixed in 40 mL Methanol under vigorous stirring at room temperature with the subsequent addition of 0.2521 g of Oxalic acid monohydrate. The mixture was then transferred to a 100 mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave and kept in an oven at 200 °C for 24 hours. The obtained powder was then washed repeatedly with Ethanol and Acetone and dried overnight. Finally, the precipitates were calcined at 400–500 °C for 4 hours under H2/N2 reducing atmosphere to ensure the formation of spinel compounds.

Characterization

The crystallinity of the samples was characterized using X-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα (λ = 1.5418 Å) generated at 45 kV and 30 mA. The data were gathered in the 2θ range of 10° to 80° with a scan rate of 0.05°∙sec−1. XRD data were analyzed using General Structure Analysis System (GSAS) software to obtain Rietveld Refinement. The elemental compositions were analyzed through X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS, JEOL Photoelectron Spectrometer (ESCA), JPS-9200, monochromatic Al-Kα), V K-edge X-ray absorption spectra (XAS conducted at National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center (NSRRC), Hsinchu, Taiwan using BL01C1 and BL17C1 beamlines) and Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS, X-MAX). The morphology and elemental mapping and crystal structure of the samples were analyzed via tunneling electron microscope Cs-corrected Scanning Transmission Electron Microscope (FEI-Titan3 G2-60-300 operating at 200 kV and scanning electron microscope (SEM) – Hitachi S-4100. For ex-situ XRD characterizations, the batteries were opened after designated charge and discharge voltages inside an Ar-gas filled glove box with with H2O and O2 content <0.5 ppm. The anode electrodes were carefully collected, washed with dimethyl carbonate (DMC) to remove the electrolyte and were vacuumed overnight to remove excess solvents.

Electrochemical Measurement

The electrochemical performances of the batteries were measured by assembling CR2032 coin cells. Two slurries were prepared with similar compositions of 70:15:15 for active material (FeV2O4), Super-P (Carbon black, 40 nm), and binder. For aqueous based binder, 9 wt.% of CMC (Mw = 2 × 105 Da) and 6 wt. % of SBR was dissolved in DI H2O. Meanwhile, 15 wt. % of PVdF (Mw = 1 × 106 Da) was dissolved in NMP. The prepared slurries were coated onto 10 μm copper foil which was used as the working electrode of the battery. The samples were punched (14 mm) and dried at 120 °C for 8 h in vacuum system to remove the residual solvents. The batteries were assembled in an Ar-gas filled glove box with H2O and O2 content <0.5 ppm using sodium disks as the counter electrode, 1 M of NaClO4 in ethylene carbonate (EC) and diethyl carbonate (DEC) (1:1 in volume ratio) as electrolyte, and glass fiber filter disks as the separators. The discharge/charge tests were analysed using AcuTech System in the voltage range of 0.01 V and 3.0 V at room temperature constant voltage charge process. The mass loading of these sample is in the range of 2.60 ± 0.30 mg/cm2. The cyclic voltammograms (CV) were measured by CH Instruments Analyzer CHI 6273E at a scan rate of 0.1 mV·s−1 between 0.01 V and 3.0 V and the Electrochemical Impedance of the samples were tested in the frequency range from 0.01-100000 Hz. For the ex-situ analyses, the electrodes were opened inside an Ar-gas filled glove box with H2O and O2 content <0.5 ppm. The electrodes were washed with dimethyl carbonate (DMC) to remove excess electrolytes and were dried inside the vacuum chamber overnight to prevent oxidation.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the National Science Council of Taiwan under contract numbers: 102-2221-E-033-050-MY2 and 102-3011-P-033-003. It is also partially funded by Hokkaido University, microstructural characterization platform as a program of Nanotechnology Platform of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan.

Author Contributions

W.R.L., T.Y. and M.T.N. supervised the research and contributed editing of manuscript. All authors discussed and commented on the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Irish Valerie B. Maggay, Lyn Marie Z. De Juan and Jeng-Shin Lu contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-27083-z.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kim SW, Seo DH, Ma X, Ceder G, Kang K. Electrode materials for rechargeable sodium‐ion batteries: potential alternatives to current lithium‐ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2012;2:710–721. doi: 10.1002/aenm.201200026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qu B, et al. Layered SnS2‐Reduced Graphene Oxide Composite–A High‐Capacity, High‐Rate, and Long‐Cycle Life Sodium‐Ion Battery Anode Material. Adv. Mater. 2014;26:3854–3859. doi: 10.1002/adma.201306314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slater MD, Kim D, Lee E, Johnson CS. Sodium‐ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013;23:947–958. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201200691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng C, Zeng L, Wang M, Zheng H, Wei M. Synthesis of hierarchical ZnV2O4 microspheres and its electrochemical properties. CrystEngComm. 2014;16:10309–10313. doi: 10.1039/C4CE01445F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaliyappan K, Liu J, Lushington A, Li R, Sun X. Highly Stable Na2/3(Mn0. 54Ni0. 13Co0. 13) O2 Cathode Modified by Atomic Layer Deposition for Sodium‐Ion Batteries. ChemSusChem. 2015;8:2537–2543. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201500155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krengel M, Adelhelm P, Klein F, Bensch W. FeV2S4 as a high capacity electrode material for sodium-ion batteries. ChemComm. 2015;51:13500–13503. doi: 10.1039/c5cc04022a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jian Z, et al. Superior electrochemical performance and storage mechanism of Na3V2(PO4)3 cathode for room‐temperature sodium‐ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2013;3:156–160. doi: 10.1002/aenm.201200558. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu Y, Zhu Y, Liu Y, Wang C. Electrochemical performance of porous carbon/tin composite anodes for sodium‐ion and lithium‐ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2013;3:128–133. doi: 10.1002/aenm.201200346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Q, et al. Facile synthesis of FeSi4P4 and its Sodium Ion Storage Performance. Electrochim. Acta. 2017;247:820–825. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2017.07.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang X, Liu H, Song J, Yin C, Xu H. Hierarchical mesoporous octahedral K2Mn1− xCoxFe(CN)6 as a superior cathode material for sodium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2016;4:16205–16212. doi: 10.1039/C6TA06658E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim Y, Ha KH, Oh SM, Lee KT. High‐Capacity Anode Materials for Sodium‐Ion Batteries. Chem. Eur. J. 2014;20:11980–11992. doi: 10.1002/chem.201402511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Y, Zhang N, Yu C, Jiao L, Chen J. MnFe2O4@C nanofibers as high-performance anode for sodium-ion batteries. Nano Lett. 2016;16:3321–3328. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b00942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krengel M, et al. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017. CuV2S4: A high rate-capacity and stable anode material for sodium-ion batteries; pp. 21283–21291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang Y, et al. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017. Enhancing Sodium-Ion Storage Behaviors in TiNb2O7 by Mechanical BallMilling; pp. 8696–8703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Su D, Dou S, Wang G. Hierarchical Vanadium Pentoxide Spheres as High‐Performance Anode Materials for Sodium‐Ion Batteries. ChemSusChem. 2015;8:2877–2882. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201500139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim S-O, Manthiram A. The facile synthesis and enhanced sodium-storage performance of a chemically bonded CuP2/C hybrid anode. ChemComm. 2016;52:4337–4340. doi: 10.1039/c5cc10585d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Su H, Jaffer S, Yu H. Transition metal oxides for sodium-ion batteries. Energy Storage Materials. 2016;5:116–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ensm.2016.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pan H, Hu Y-S, Chen L. Room-temperature stationary sodium-ion batteries for large-scale electric energy storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013;6:2338–2360. doi: 10.1039/c3ee40847g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu Y, et al. Electrospun Sb/C fibers for a stable and fast sodium-ion battery anode. ACS nano. 2013;7:6378–6386. doi: 10.1021/nn4025674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Y, Wang C, Guo H, Wang Y, Huang Z. A nitrogen-doped three-dimensional carbon framework for high performance sodium ion batteries. RSC Adv. 2017;7:1588–1592. doi: 10.1039/C6RA27088C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee J-W, Shin H-S, Lee C-W, Jung K-N. Carbon-and Binder-Free NiCo2O4 Nanoneedle Array Electrode for Sodium-Ion Batteries: Electrochemical Performance and Insight into Sodium Storage Reaction. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2016;11:45. doi: 10.1186/s11671-016-1271-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang Y, et al. Transition metal oxides for high performance sodium ion battery anodes. Nano Energy. 2014;5:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2014.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevens D, Dahn J. High capacity anode materials for rechargeable sodium‐ion batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2000;147:1271–1273. doi: 10.1149/1.1393348. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo W, et al. Na-ion battery anodes: materials and electrochemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016;49:231–240. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Darwiche A, et al. Better cycling performances of bulk Sb in Na-ion batteries compared to Li-ion systems: an unexpected electrochemical mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:20805–20811. doi: 10.1021/ja310347x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chevrier VL, Ceder G. Challenges for Na-ion negative electrodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2011;158:A1011–A1014. doi: 10.1149/1.3607983. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poizot P, Laruelle S, Grugeon S, Dupont L, Tarascon J. Nano-sized transition-metal oxides as negative-electrode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Nature. 2000;407:496. doi: 10.1038/35035045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu J, Li H, Huang X, Chen L. Improve the electrochemical performances of Cr2O3 anode for lithium ion batteries. Solid State Ion. 2006;177:2791–2799. doi: 10.1016/j.ssi.2006.03.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cabana, J., Monconduit, L., Larcher, D. & Palacin, M. R. Beyond Intercalation‐Based Li‐Ion Batteries: The State of the Art and Challenges of Electrode Materials Reacting Through Conversion Reactions. Adv. Mater. 22 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.He C, et al. Carbon-encapsulated Fe3O4 nanoparticles as a high-rate lithium ion battery anode material. ACS nano. 2013;7:4459–4469. doi: 10.1021/nn401059h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Z, Huang X, Hu J, Stein A, Tang B. Synthesis and electrochemical performance of three-dimensionally ordered macroporous CoCr2O4 as an anode material for lithium ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta. 2017;247:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2017.07.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alcántara R, Jaraba M, Lavela P, Tirado J. NiCo2O4 spinel: First report on a transition metal oxide for the negative electrode of sodium-ion batteries. Chem. Mater. 2002;14:2847–2848. doi: 10.1021/cm025556v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yan N, Xu Y, Li H, Chen W. The preparation of FeVO4 as a new sort of anode material for lithium ion batteries. Mater. Lett. 2016;165:223–226. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2015.11.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu X, et al. Alkaline earth metal vanadates as sodium-ion battery anodes. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:460. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00211-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zeng L, et al. ZnV2O4–CMK nanocomposite as an anode material for rechargeable lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. 2012;22:14284–14288. doi: 10.1039/c2jm32138f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu X, et al. Nanophase ZnV2O4 as stable and high capacity Li insertion electrode for Li-ion battery. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2015;15:435–440. doi: 10.1016/j.cap.2015.01.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang L, et al. Acetylene black induced heterogeneous growth of macroporous CoV2O6 nanosheet for high-rate pseudocapacitive lithium-ion battery anode. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2016;8:7139–7146. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b00596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prahasini P, et al. A novel attempt for employing brannerite type copper vanadate as an anode for lithium rechargeable batteries. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2016;27:3292–3297. doi: 10.1007/s10854-015-4157-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morcrette M, et al. A reversible copper extrusion-insertion electrode for rechargeable Li batteries. Nat. Mater. 2003;2:755. doi: 10.1038/nmat1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu X, Cao Y, Zheng H, Chen X, Feng C. Synthesis and modification of FeVO 4 as novel anode for lithium-ion batteries. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017;394:183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.09.133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Augustyn V, Dunn B. Low-potential lithium-ion reactivity of vanadium oxide aerogels. Electrochim. Acta. 2013;88:530–535. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2012.10.145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu, S. et al. Synthesis and Application of Iron-based Nanomaterials as Anode of Lithium-Ion Batteries and Supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A, 10.1039/C8TA01683F (2018).

- 43.Myoung BR, Kim SJ, Lim JT, Kouh T, Kim CS. Microscopic evidence of magnetic and structure phase transition in multiferroic spinel FeV2O4. AIP Adv. 2017;7:055828. doi: 10.1063/1.4977549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wakihara M, Shimizu Y, Katsura T. Preparation and magnetic properties of the FeV2O4 Fe3O4 system. J. Solid State Chem. 1971;3:478–483. doi: 10.1016/0022-4596(71)90089-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.MacDougall G, et al. Magnons and a two-component spin gap in FeV2O4. Phys. Rev. B. 2014;89:224404. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.89.224404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chou S-L, Pan Y, Wang J-Z, Liu H-K, Dou S-X. Small things make a big difference: binder effects on the performance of Li and Na batteries. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014;16:20347–20359. doi: 10.1039/C4CP02475C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang W, Dahbi M, Komaba S. Polymer binder: a key component in negative electrodes for high-energy Na-ion batteries. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2016;13:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.coche.2016.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maleki H, Deng G, Kerzhner‐Haller I, Anani A, Howard JN. Thermal Stability Studies of Binder Materials in Anodes for Lithium‐Ion Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2000;147:4470–4475. doi: 10.1149/1.1394088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li J, Christensen L, Obrovac M, Hewitt K, Dahn J. Effect of heat treatment on Si electrodes using polyvinylidene fluoride binder. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2008;155:A234–A238. doi: 10.1149/1.2830545. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu G, et al. Optimization of acetylene black conductive additive and PVDF composition for high-power rechargeable lithium-ion cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2007;154:A1129–A1134. doi: 10.1149/1.2792293. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Choi D, et al. Li-ion batteries from LiFePO4 cathode and anatase/graphene composite anode for stationary energy storage. Electrochem. Commun. 2010;12:378–381. doi: 10.1016/j.elecom.2009.12.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fedorková A, et al. PPy doped PEG conducting polymer films synthesized on LiFePO4 particles. J. Power Sources. 2010;195:3907–3912. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2010.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yabuuchi N, Kubota K, Dahbi M, Komaba S. Research development on sodium-ion batteries. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:11636–11682. doi: 10.1021/cr500192f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang R, et al. Water soluble styrene butadiene rubber and sodium carboxyl methyl cellulose binder for ZnFe2O4 anode electrodes in lithium ion batteries. J. Power Sources. 2015;285:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2015.03.100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang Q, et al. Ordering process and ferroelectricity in a spinel derived from FeV2O4. Phys. Rev. B. 2012;85:054405. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.85.054405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hager, H., Greiner, S., Heubl, G. & Stahl-Biskup, E. Hagers Handbuch der Pharmazeutischen Praxis: Drogen PZ Folgeband 2. (Springer-Verlag, 2013).

- 57.Wong J, Lytle FW, Messmer RP, Maylotte DH. K-edge absorption spectra of selected vanadium compounds. Phys. Rev. B. 1984;30:5596–5610. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.30.5596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nabavi M, Sanchez C, Livage J. Structure and properties of amorphous V2O5. Philos. Mag. 1991;63:941–953. doi: 10.1080/13642819108205549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang W, Jiang B, Hu L, Jiao S. Nasicon material NaZr2(PO4)3: a novel storage material for sodium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2014;2:1341–1345. doi: 10.1039/C3TA14310D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang H, et al. Cobalt oxide-carbon nanosheet nanoarchitecture as an anode for high-performance lithium-ion battery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2015;7:2882–2890. doi: 10.1021/am508208c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim Y, et al. Probing the additional capacity and reaction mechanism of the RuO2 anode in lithium rechargeable batteries. ChemSusChem. 2015;8:2378–2384. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201403488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee B-R, Oh E-S. Effect of molecular weight and degree of substitution of a sodium-carboxymethyl cellulose binder on Li4Ti5O12 anodic performance. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2013;117:4404–4409. doi: 10.1021/jp311678p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lestriez B, Bahri S, Sandu I, Roué L, Guyomard D. On the binding mechanism of CMC in Si negative electrodes for Li-ion batteries. Electrochem. Commun. 2007;9:2801–2806. doi: 10.1016/j.elecom.2007.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chong J, et al. A comparative study of polyacrylic acid and poly (vinylidene difluoride) binders for spherical natural graphite/LiFePO4 electrodes and cells. J. Power Sources. 2011;196:7707–7714. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2011.04.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang Y, Huang H, Xie Q, Wang Y, Qu B. Rational design of graphene-encapsulated NiCo2O4 core-shell nanostructures as an anode material for sodium-ion batteries. J. Alloy. Comp. 2017;705:314–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2017.02.161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang, N. et al. 3D Porous γ‐Fe2O3@C Nanocomposite as High‐Performance Anode Material of Na‐Ion Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 5 (2015).

- 67.Zhou K, et al. A multi-functional gum arabic binder for NiFe2O4 nanotube anodes enabling excellent Li/Na-ion storage performance. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2017;5:18138–18147. doi: 10.1039/C7TA05219G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li J, et al. Hollow MnCo2O4 submicrospheres with multilevel interiors: from mesoporous spheres to yolk-in-double-shell structures. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2013;6:24–30. doi: 10.1021/am404841t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gao M, et al. FeO/C anode materials of high capacity and cycle stability for lithium-ion batteries synthesized by carbothermal reduction. J. Alloy. Comp. 2013;565:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2013.03.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jiang H, et al. Ultrafine V2O3 nanowire embedded in carbon hybrids with enhanced lithium storage capability. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2015;54:2960–2965. doi: 10.1021/acs.iecr.5b00132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xu, D. et al. A Hierarchical N/S‐Codoped Carbon Anode Fabricated Facilely from Cellulose/Polyaniline Microspheres for High‐Performance Sodium‐Ion Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 6 (2016).

- 72.Augustyn V, et al. High-rate electrochemical energy storage through Li+ intercalation pseudocapacitance. Nat. Mater. 2013;12:518–522. doi: 10.1038/nmat3601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhu S, et al. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2016. NiSe2 nanooctahedra as an anode material for high-rate and long-life sodium-ion battery; pp. 311–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ma X, An K, Bai J, Chen H. NaAlTi3O8, A Novel Anode Material for Sodium Ion Battery. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:162. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00202-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang S, Xu K, Jow T. Electrochemical impedance study on the low temperature of Li-ion batteries. Electroch. Acta. 2004;49:1057–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2003.10.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ong T, Yang H. Lithium intercalation into mechanically milled natural graphite: electrochemical and kinetic characterization. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2002;149:A1–A8. doi: 10.1149/1.1420705. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.