Abstract

Integration of public genome-wide gene expression data together with Cox regression analysis is a powerful weapon to identify new prognostic gene signatures for cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a major cause of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), however, it remains largely unknown about the specific gene prognostic signature of HBV-associated HCC. Using Robust Rank Aggreg (RRA) method to integrate seven whole genome expression datasets, we identified 82 up-regulated genes and 577 down-regulated genes in HBV-associated HCC patients. Combination of several enrichment analysis, univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis, we revealed that a three-gene (SPP2, CDC37L1, and ECHDC2) prognostic signature could act as an independent prognostic indicator for HBV-associated HCC in both the discovery cohort and the internal testing cohort. Gene set enrichment analysis showed that the high-risk group with lower expression levels of the three genes was enriched in bladder cancer and cell cycle pathway, whereas the low-risk group with higher expression levels of the three genes was enriched in drug metabolism-cytochrome P450, PPAR signaling pathway, fatty acid and histidine metabolisms. This indicates that patients of HBV-associated HCC with higher expression of these three genes may preserve relatively good hepatic cellular metabolism and function, which may also protect HCC patients from persistent drug toxicity in response to various medication. Our findings suggest a three-gene prognostic model that serves as a specific prognostic signature for HBV-associated HCC.

Keywords: Hepatitis B virus associated hepatocellular carcinoma, Robust Rank Aggreg analysis, Hub genes, Prognostic signature, Overall survival.

Introduction

In recent years, high-throughput expression profiling data from microarray chip and RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) provide useful information regarding the mechanisms and diversity of various cancers, and are valuable for the diagnosis, therapeutic response prediction and prognosis evaluation in those diseases 1. However, there are many obstacles in data preparation, analysis and interpretation because the results from one individual study can be rather noisy. Therefore, integration of the public genome-wide gene expression data is a powerful weapon for cancer diagnosis and prognosis 2.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most prevalent cancers worldwide and the second cause of death among malignancy tumors 3. Although more than 40 prognostic gene signatures have been described in HCC, none has become a commercial marker useful for clinical decision-making 4, 5. Therefore, identifying a more specific gene prognostic signature for HCC with a specific etiology still represents a critical approach for the diagnosis and prognosis of HCC.

Over 50% of HCC cases worldwide are attributed to hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. In areas with high HBV prevalence, such as Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, more than 80% of patients with HCC are due to HBV infection 6. Chronic HBV infection plays critical roles in the progression of HCC and patients with HBV-associated HCC usually have poor clinical recovery and high rate of recurrence after treatment 7. Control of HBV infection is effective to reduce the mortality of HCC patients in East Asia and Southern Europe 8. Because of the integration of HBV DNA into host cellular DNA, and also the expression of HBV proteins that have direct effect on cellular functions 9, the pathogenesis of HBV-associated HCC has its own specific gene signatures as compared to other types of HCC 10-12. Recently, semi-supervised methods to predict patient survival from gene expression data have been widely accepted. These methods allow us to use the expression of some critical genes, also known as prognostic genes, to predict the survival of future patients and also the efficiency of therapeutic treatment 13. As such, screening of HBV specific prognostic gene models is ultimately important for the diagnosis and prognosis of patients with HBV-associated HCC. However, no specific gene prognostic model has been developed for HBV-associated HCC until now.

In this current study, the R package called Robust Rank Aggreg (RRA) was used to integrate several HBV-associated HCC experimental sources, which is helpful to identify evidence-supported findings and to increase the signal as well as to minimize rates of false positive findings 14. By using the gene cluster of differential expressed genes acquired from RRA, we performed bioinformatics analysis of weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) 15 to identify key gene modules, following by construction of the protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks for the key gene modules in order to further identify hub genes. Lastly, we identified a three-gene prognostic signature in these hub genes by univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis from the GSE14520 dataset.

Materials and Methods

Collection of HBV-associated HCC gene expression datasets

All HBV-associated HCC datasets were downloaded from GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). Every dataset was estimated thoroughly through full text. The selection criteria used in this study are as follows: 1. gene expression profiling datasets that included gene microarray chip technology or RNA-Seq technique; 2. studies comparing gene expressions between HBV-associated cancer and non-cancerous liver tissue in human samples; 3. expression studies using cell lines or body fluid (such as serum, saliva, peripheral blood, etc.) were excluded; 4. sample size should be larger than three pairs. According to the above screening criteria, 7 datasets were finally included in this study: GSE77509 16, GSE62232 17, GSE25097 18, GSE54238 19, GSE50579 20, GSE14520 21, and GSE55092 22 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies

| First author and reference | Region | Number of samples | Year | GEO accession | Platforms | Data Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yang Y et al 9 | China | 17 pair | 2017 | GSE77509 | GPL16791 | RNA-seq |

| Schulze K et al 10 | France | 10T,10N | 2015 | GSE62232 | GPL570 | Gene Chip |

| Sung WK et al 11 | USA | 223T,243N | 2011 | GSE25097 | GPL10687 | Gene Chip |

| Yuan SX et al 12 | USA | 26T,10N | 2016 | GSE54238 | GPL16955 | Gene Chip |

| Neumann O et al 13 | Germany | 8T,10N | 2012 | GSE50579 | GPL14550 | Gene Chip |

| Roessler S et al 14 | USA | 212 pair | 2010 | GSE14520 | GPL571 GPL3921 | Gene Chip |

| Melis M et al 15 | USA | 39T,81N | 2014 | GSE55092 | GPL570 | Gene Chip |

Note: T, tumor samples; N, non-cancerous samples; pairs, tumor tissues and non-cancerous tissues from the same patient.

Datasets processing and statistical analysis

Series matrix files of each dataset were downloaded from GEO. Normalization of the microarray datasets was performed by the package limma of R (version 3.3.3), and normalization of the RNA-seq datasets was performed by the package edgeR of R (version 3.3.3) 23. We used R package RRA to identify the most significant genes, and the new data frame results were constructed with the standard of P value < 0.01 14.

Enrichment analysis

To conduct enrichment analyses, the package cluster Profiler (version 3.2.14) of R (version 3.3.3) was used for analyzing the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways and Gene Ontology (GO) processes, as described previously 24, 25.

WGCNA

WGCNA is a typical systemic biological method for describing correlation patterns among genes and identifying modules of highly correlated genes by using average linkage hierarchical clustering coupled with the topological overlap dissimilarity measure based on high-throughput chip data or RNA-Seq data 26-28. In current study, WGCNA package (version 1.60) in R was used to merge highly correlated genes and identify key modules based on the expression levels of the most significant genes, identified by RRA methods above, from the data of GSE77509 16. Here, the power of β = 18 (scale free R2 = 0.8) was selected as the soft-thresholding to ensure a scale-free network. The cut Height = 0.7 and min Size = 10 were used to identify key modules. The gene modules were labeled with different colors and the grey module showed the genes that cannot be merged.

PPI network construction and clusters analysis

STRING (https://string-db.org/) was employed to construct PPI networks for distance-related genes by using the genes in the biggest module identified by WGCNA 29. The PPI networks were then exported from STRING and imported into Cytoscape. We then used the “Molecular Complex Detection (MCODE)” Cytoscape app to identify discrete clusters from the former PPI networks using default settings (K-Core: 2; degree cutoff: 2; max. depth: 100 and node score cutoff: 0.2 were used as the cutoff criteria for the identification of network modules) 30. The top clusters were screened under the conditions of minimum size = 6 and minimum score = 6.

Generation and validation of prognostic signature and statistical analysis

The data of Roessler S's study (GEO DataSet: GSE14520), which contained the data of both gene expression levels and clinical signatures of 212 HBV-associated HCC patients, were used for the generation and validation of prognostic signature using the package of survminer and survival of R (version 3.3.3). Firstly, the univariate Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to evaluate the associations between overall survival (OS) and the expression level of each hub gene that belong to the top cluster identified by PPI networks and MCODE Cytoscape app (P < 0.05 was considered significant). Hazard ratios (HRs) were applied to identify protective (HR < 1) and risk genes (HR > 1). Secondly, we divided the data of these 212 patients randomly into two groups: a discovery cohort (N = 106) and an internal testing cohort (N = 106). Thirdly, in the discovery cohort, protective or risk genes identified by univariate Cox analysis were selected to calculate the association with OS by multivariable Cox analysis, and the risk scores for predicting OS was calculated with the formula based on the protective or risk genes: Risk scores = expgene1*β1 + expgene2*β2 +…+expgenen*βn. The “β” value is the estimated regression coefficient of gene derived from the multivariate Cox analysis and “exp” indicates the expression profiles of gene 31. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with the log-rank test (P < 0.05) was used to examine the proportional assumptions for Cox proportional hazard model. Lastly, the prognostic signature of indicated genes generated in the discovery cohort was further confirmed in the internal testing cohort. The statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)

GSEA was performed with indicated prognostic genes using phenotype labels “high-risk” vs “low-risk” by the GSEA software (http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp). Gene sets used in this work were c2.cp.kegg.v5.2.symbols.gmt downloaded from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB, http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp)

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were accomplished using R (version 3.3.3). The association between clinical characteristics and group was determined using chi-square test, wilcoxon rank sum test or unpaired t test according the data type of clinical characteristics. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression models were used to evaluate prognostic significance. Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan-Meier and log-rank test. The Student's t-test was used for comparisons of two independent groups. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Identified significance genes by integrated analysis

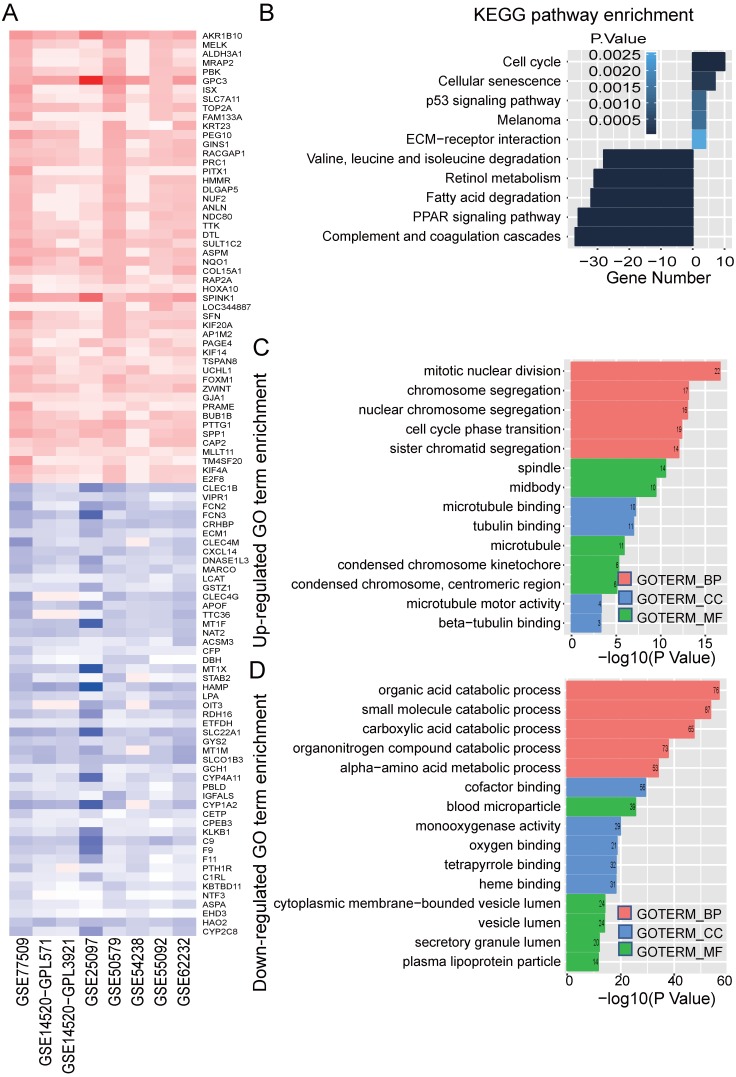

In order to identify significance genes in HBV-associated HCC, we setup a workflow showing in Figure 1. By using the method of RRA to integrate 7 datasets, 82 up-regulated genes and 577 down-regulated genes were identified as the most significant genes [Table S1, P < 0.01]. The top 50 significantly up-regulated and down-regulated genes were listed in Figure 2A. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the most significant up-regulated genes showed that the top 5 enriched pathway is cell cycle, cellular senescence, melanoma, p53 signaling pathway, and ECM-receptor interaction. All of these pathways were reported with important roles in cancer 32-35 (Figure 2B). Whereas the top 5 KEGG pathway enriched in the down-regulated genes, including valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation, retinol metabolism, PPAR signaling pathway, fatty acid degradation and complement and coagulation cascades, also have been studied to be important pathways involved in tumor growth and metastasis (Figure 2B and Table S2) 36-39. Together with the data of GO analysis (Figure 2C, 2D, and Table S3), these significant genes are shown to be mainly involved in tumor metabolism and growth.

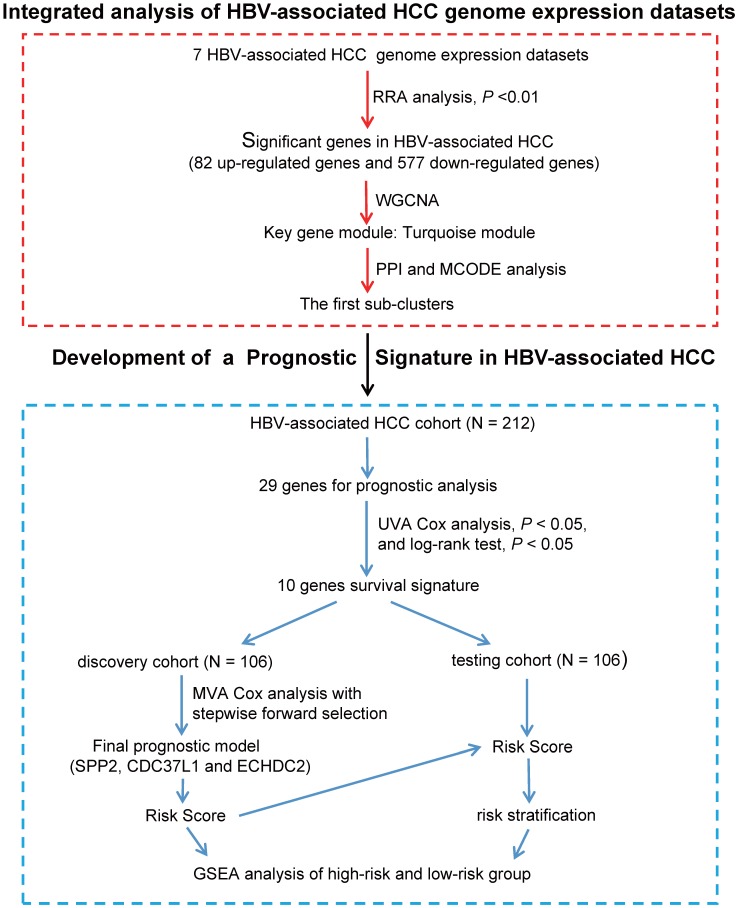

Figure 1.

Flowchart describing the schematic overview of the study design. After integrated analysis and different bioinformatics analysis of HBV-associated HCC genome expression datasets, we identified hub genes in Cluster 1. Hub genes were then analyzed individually for prognostic significance by univariate Cox proportional hazards and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. 10 hub genes were significantly associated with the survival of patients with HBV-associated HCC (UVA Cox analysis, P < 0.05, and log-rank test P < 0.05). The HBV-associated HCC cohort (GSE14520, N = 212) were randomly divided in to discovery cohort (N = 106) and internal testing cohort (N = 106). Next, we used multivariable Cox proportional hazards stepwise regression analysis with forward selection to build a prognostic model that included 3 genes: SPP2, ECHDC2, and CDC37L1. This model was used to calculate risk scores for discovery cohort (risk score = expSPP2* - 0.1941 + expCDC37L1* - 0.5466 + expECHDC2* - 0.4714), and the cut-off point was chosen. This risk score calculation and cut-off point were further validated in internal testing cohort. Lastly, GSEA analysis of the high-risk and low-risk group was used to further inquiry the 3 genes prognostic signature. UVA Cox: univariate Cox; MVA Cox: multivariate Cox.

Figure 2.

Identified significance genes and enrichment analysis. (A) Heatmap showed the fold change of the top 100 significantly genes in different studies (50 up-regulated genes and 50 down-regulated genes) by Robust Rank Aggreg (RRA) methods from 7 different datasets. Each row represents the same mRNA and each column represents the same study. The fold change intensity of each mRNA in one study is represented in shade of red or blue. Red represents the fold change of up-regulated genes and blue represents the fold change of down-regulated genes, respectively, in comparison to non-tumor tissues. (B) Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis of the significant genes. Up-regulated KEGG pathways are showed with horizontal axis > 0, and down-regulated genes are showed with horizontal axis < 0, respectively. The size of the horizontal axis shows the numbers of enriched genes in each KEGG pathway and the color shade of bar reflects P value. (C-D) Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of up-regulated (C) and down-regulated genes (D). The vertical and horizontal axes represent GO term and -log10 (P value) of the corresponding GO term, respectively. The number in each bar reflects the enriched gene number of each GO term. Different colors reflect main categories of GO terms: BP, biological process; CC, cellular component; MF, molecular function.

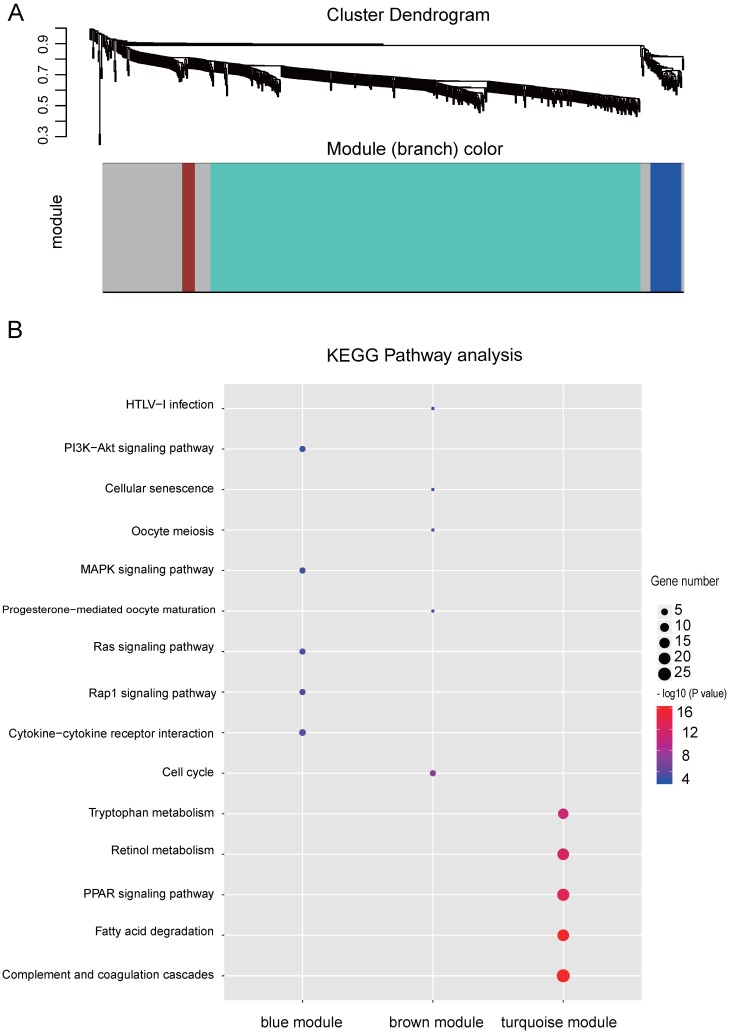

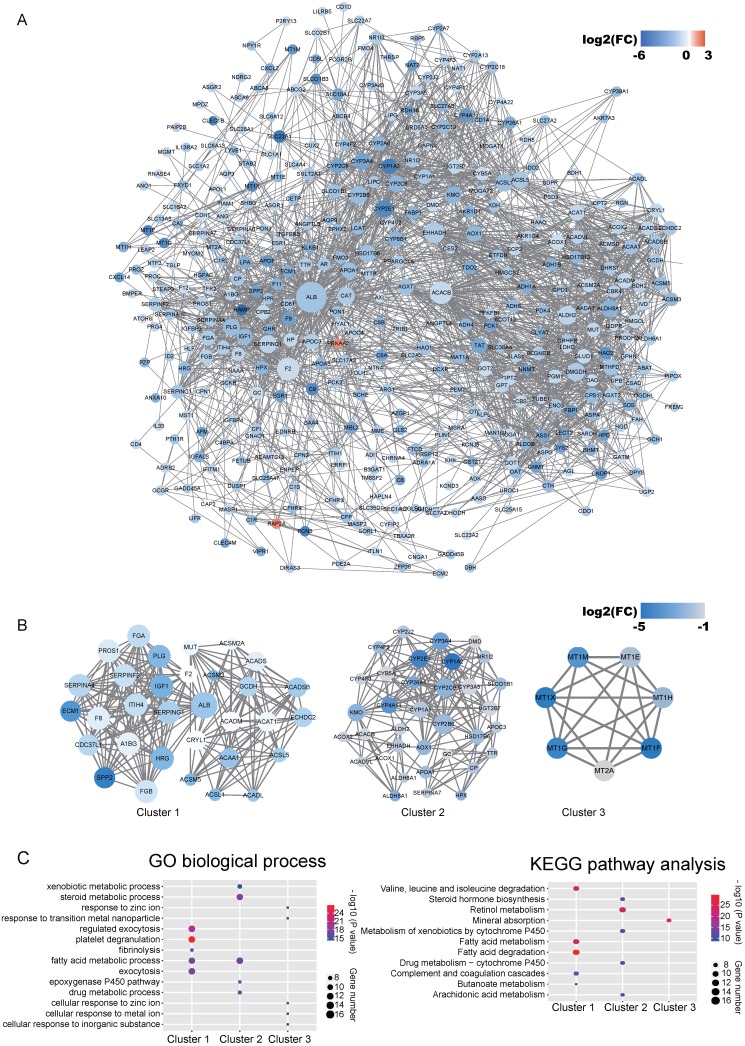

WGCNA and PPI analysis

Co-expression network by WGCNA analysis revealed that the most significant genes mentioned above were grouped into 3 modules, of which the turquoise module was the most significant one (Figure 3A and Table S4). KEGG pathway enrichment analysis showed that the turquoise module is mainly involved in the PPAR signaling and different metabolism pathway, similar to the enriched KEGG pathways involving by the most significant genes 40-42 (Figure 3B). We further constructed the PPI networks of the turquoise module by STRING, of which the largest connected master network containing 396 nodes (Figure 4A). In this largest connected master network, three discrete sub-clusters were extracted using the MCODE app by Cytoscape software 30 (Figure 4B). GO enrichment analysis of these three discrete sub-clusters revealed that Cluster 1, the largest cluster containing 32 genes was mainly involved in platelet degranulation, fatty acid metabolic process and exocytosis (Figure 4C and Table S5). KEGG pathway analysis revealed that Cluster 1 was mainly involved cellular metabolism: including fatty acid degradation, fatty acid metabolism and valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation (Figure 4C and Table S5). This indicates that Cluster 1 may play a critical role in the pathogenesis of HCC, as platelet degranulation, fatty acid metabolism and degradation have been reported to have important roles in the development of HCC 36, 43, 44.

Figure 3.

WGCNA analysis of the significant genes and KEGG analysis of the key modules from WGCNA. (A) Gene clustering and module identification by WGCNA analysis based on the dataset of GSE77509. Top: clustering dendrogram showed the result of hierarchical clustering, and each line represents one gene. Bottom: the colored row below the dendrogram indicates module membership identified by the static tree cutting method. Different color represents different co-expression network modules for the significantly genes. (B) KEGG analysis of the top three modules from WGCNA. The vertical and horizontal axes represent the KEGG pathways and different modules, respectively. The size and the color intensity of a circle represent gene number and -log10 (P value), respectively.

Figure 4.

Identified discrete clusters and enrichment analysis of the turquoise module in Figure 3. (A) PPI network of genes in the turquoise module. The color intensity in each node represents the fold change of the gene in comparison to non-tumor samples (up-regulation of a gene is shown in red and down-regulation of a gene is shown in blue). The size of the circle is proportional to the score of PPI based on the STRING database. (B) Main sub-clusters from the master PPI networks. The color intensity in each node was proportional to fold change of each gene expression in comparison to non-tumor samples (up-regulation in red and down-regulation in blue). (C) KEGG and GO enrichment analysis of the top three sub-clusters. The vertical and horizontal axes represent the GO biological process /KEGG pathways and different sub-clusters, respectively. The size and the color intensity of a circle represent gene number and -log10 (P value), respectively.

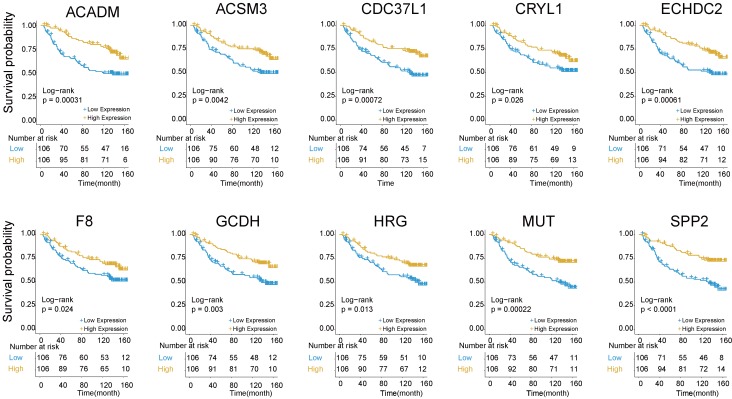

Identification of hub genes in Cluster 1 by univariate Cox proportional hazards regression model

The above findings that Cluster 1 genes were mainly involved in platelet degranulation, fatty acid metabolism and degradation prompted us to explore its prognostic value in HBV-associated HCC. To identify prognosis-related genes in this network, we first used an univariate Cox proportional hazards regression model to evaluate the associations between the expression level of the involved genes in Cluster 1 and OS by using the data reported by Roessler S et al (GEO DataSet: GSE14520) 21. The data revealed that 10 out of 32 genes, including acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, C-4 To C-12 straight chain (ACADM), acyl-coA synthetase medium-chain family member 3 (ACSM3), cell division cycle 37 like 1 (CDC37L1), crystallin lambda 1 (CRYL1), enoyl-CoA hydratase domain containing 2 (ECHDC2), coagulation factor VIII (F8), glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase (GCDH), histidine rich glycoprotein (HRG), methylmalonyl-CoA mutase (MUT) and secreted phosphoprotein 2 (SPP2), were all negatively relevant to OS in patients of HBV-associated HCC (P < 0.05, and log-rank test P < 0.05) (Figure 5 and Table S6).

Figure 5.

Kaplan-Meier survival plots of the association between the expression levels of hub genes and overall survival probability in patients of HBV-associated HCC. P values were obtained from Log-rank test. Yellow and blue line represent the samples with the gene higher expressed and lower expressed, respectively. The table below the Kaplan-Meier survival plots showed the number of patients at the risk. Abbreviations: ACADM, acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, C-4 To C-12 straight chain; ACSM3, acyl-coA synthetase medium-chain family member 3; CDC37L1, cell division cycle 37 like 1; CRYL1, crystallin lambda 1; ECHDC2, enoyl-CoA hydratase domain containing 2; F8, coagulation factor VIII; GCDH, glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase; HRG, histidine rich glycoprotein; MUT, methylmalonyl-CoA mutase; SPP2, secreted phosphoprotein 2.

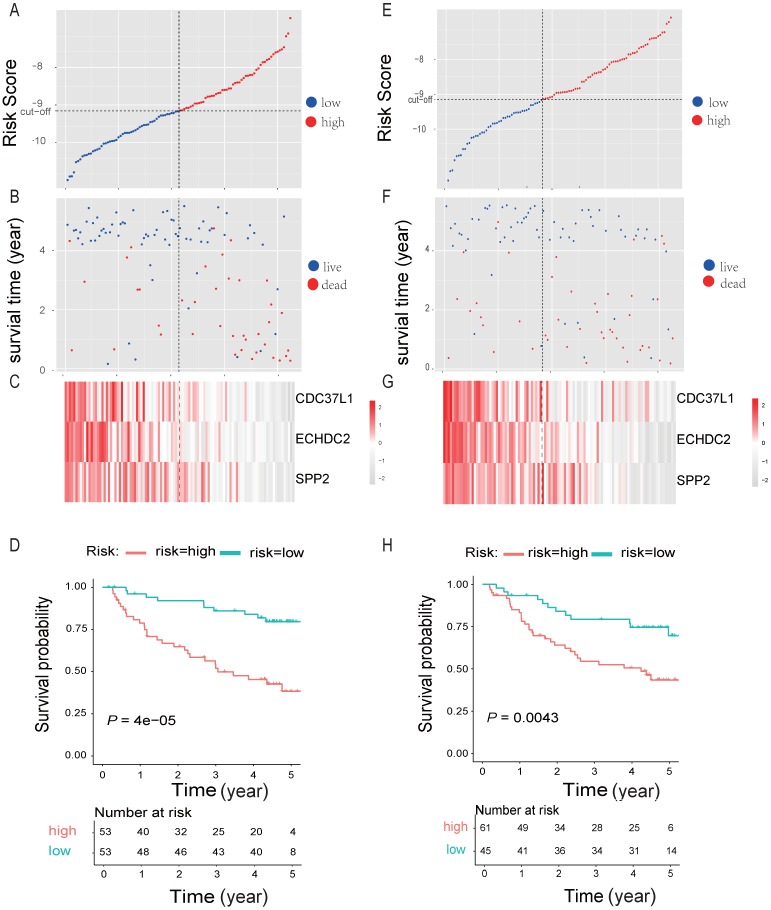

Generation and validation of multiple-gene prognostic signature by multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analysis

By randomly dividing the data of 212 HBV-associated HCC patients in Roessler et al's study (GEO DataSet: GSE14520) 21 into a discovery cohort (N = 106) and an internal testing cohort (N = 106) (Table 2, and Table S7). The 10 genes that were significantly associated with OS of HBV-associated HCC were used for prognostic module building by using forward conditional stepwise regression with multivariable Cox analysis in the discovery cohort. This procedure selected a prognostic model containing three genes, including SPP2, CDC37L1 and ECHDC2. The risk scores of these three genes signature for each sample in the discovery cohort were calculated by using the following formula: Risk score = expSPP2*-0.1941 + expCDC37L1* - 0.5466 + expECHDC2* - 0.4714 and ranked according to the values of Risk score. Using the median risk score (-9.158) as the cut-off point, patients were divided into a high-risk group (score > -9.158, N = 53) and a low-risk group (score ≤ -9.158, N = 53) (Figure 6A). Patients in high-risk group tended to express low levels of these three genes and shorter survival time (Figure 6B-C). Consistently, patients in high-risk group had lower OS rates than those in low-risk group, suggesting that patients in the high-risk group was more likely to have higher mortality than that in the low-risk group (Log-rank test, P < 0.05) (Figure 6D).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of the patients

| Clinical Variable | Discovery Cohort (n = 107) |

Internal Testing Cohort (n = 107) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 92 | 91 | 1b |

| Female | 14 | 15 | |

| Age, y | |||

| Median (range) | 51(71-27) | 50 (77-21) | 0.6054a |

| ALT | |||

| Negative (≤50 U/L) | 67 | 57 | 0.2097b |

| Positive (>50 U/L) | 39 | 49 | |

| Tumor size | |||

| Large(>5cm) | 31 | 43 | |

| Small(≤5cm) | 74 | 63 | 0.1245b |

| No data | 1 | 0 | |

| TNM stage | |||

| I | 47 | 42 | |

| II | 37 | 39 | 1c |

| III-IV | 22 | 25 | |

| AFP | |||

| Low | 56 | 59 | |

| High | 50 | 44 | 0.6117b |

| No data | 0 | 3 |

AFP, α-fetoprotein; ALT, alanine transferase; a Unpaired t test; b chi-squared test (χ2 test); c wilcoxon rank sum test.

Figure 6.

Three-gene predictor-score analysis of HBV-associated HCC patients in both the discovery and internal cohort. (A) and (E) Three-gene risk score distribution in both the discovery (A) and internal testing cohort (E), respectively. Each point represents one patient; the vertical and horizontal axes represent the risk score calculated from the three-genes model and results sorted by the size of the risk score, respectively; red and blue represent patients with high and low risk scores identified by cut-off, respectively. The black dotted line represents the median mRNA risk score cut-off dividing patients into low-risk or high-risk groups. (B) and (F) Patients' survival status and time in both the discovery (B) and internal testing cohort (F), respectively. Each point corresponds to the same patient as above; the vertical and horizontal axes represent the survival time and results sorted by the size of the risk score, respectively; red or blue represent patient dead or live in the end, respectively. (C) and (G) Heatmap of gene expression profiles in both the discovery (C) and internal testing cohort (G), respectively. Each row represents the same gene and each column represents the same patient corresponded to the above point. The expression intensity of each gene in one patient is represented in shade of red or grey, indicating its expression level above or below the median expression intensity across all patients, respectively. (D) and (H) The Kaplan-Meier overall survival plots for HBV-associated HCC risk groups obtained from both the discovery (D) and internal testing cohort (H), respectively. Red and green line represent the patient with high or low risk, respectively.

To test our findings, this three-gene risk score model was further evaluated using the internal cohort. With the same risk-score formula and cut-off point derived from the discovery cohort, the internal cohort was divided into high-risk group (N = 61) and low-risk group (N = 45). The data in internal cohort revealed a similar finding as that in the discovery cohort (Figure 6E-H).

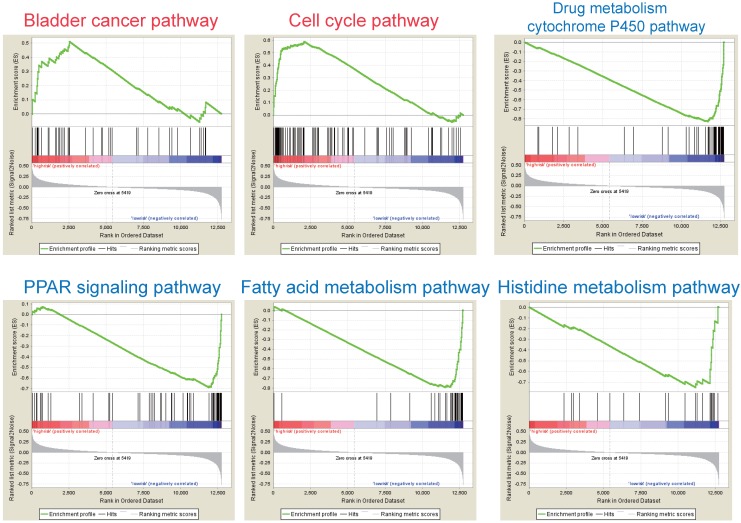

GSEA analysis

According to the above results, this three-gene model can distinguish survival difference from HBV-associated HCC patients. GSEA analyses of the data of the GSE14520 revealed that the high-risk group showed gene-enrichment in bladder cancer and cell cycle pathway (Figure 7). And the oncogenes in bladder cancer pathway were overexpressed in the tumor tissues of HBV-associated HCC patients in the high-risk group, such as MYC that can trigger specific gene amplification to promote cell growth and proliferation 45.

Figure 7.

GSEA analysis of the three prognostic genes. GSEA analysis of the differentially expressed genes between the high-risk versus low-risk group. Only two significantly functional gene sets were enriched for high-risk group (marked in red), whereas only four most significantly enriched functional gene sets were listed for low-risk group (markered in blue) in HBV-associated HCC samples.

Other overexpressed genes of bladder cancer pathway in the tumor tissue of patient in the high-risk group, such as vascular endothelial growth factor B (VEGFB), matrix metallopeptidase (MMP) 1, 2 and 9, are also reported to be involved in tumor invasion and metastasis 46-49. In the cell cycle pathway, genes associated with the proliferative capacity of tumor cells were also higher expressed in patients of high-risk group, such as minichromosome maintenance (MCM) complex 50. While, the low-risk group showed gene-enrichment in drug metabolism-cytochrome P450, PPAR signaling, and fatty acid metabolism pathway (Figure 7). These pathways, associated with hepatic metabolism of cholesterol, fatty acid and drug, are usually down-regulated in HCC patients 51, 52. This indicates that patients in the low-risk group preserve relative good capacity of hepatic function, which might also protect HCC patients from persistent drug toxicity in response to various medication. These results showed a highly similar manner with the significant changed KEGG pathways of the most significant genes in total tumor samples of HBV-associated HCC as compared to healthy tissue presented by integrational analysis (Figure 2B).

Discussion

Although increasing chip and RNA-seq profiling studies were performed to find differentially expressed genes in HBV-associated HCC, these reports often presented inconsistent results across different studies. In our current work, we used an integrated analysis by using the RRA method to identify significant differentially expressed genes from 7 independent datasets of HBV-associated HCC profiling experiments, which could overcome the rather noisy from different individual studies 53.

The expression levels of each gene were re-ranked and their significances were re-determined by giving a P-value for each gene. Finally, 82 up-regulated and 577 down-regulated integrated significant genes were identified. Many of them have been proven to be oncogenic, such as aldo-keto reductase family 1 member B10 (AKR1B10) 54, maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase (MELK) 55, and aldehyde dehydrogenase 3 family member A1 (ALDH3A1) 56). Some are considered as anti-oncogenes, such as hydroxyacid oxidase 2 (HAO2) 57, C-type lectin domain family 1 member B (CLEC1B) 58 and secreted phosphoprotein 2 (SPP2) 59 in HCC. The result of enrichment analysis also showed that these significance genes were highly related to HCC, such as the cell cycle pathway and p53 signaling pathway 32, 33. In addition, we also identified many significantly expressed genes, the role of which are still unclear and need further research in HCC, such as EH domain containing 3 (EHD3), aspartoacylase (ASPA) and melanocortin 2 receptor accessory protein 2 (MRAP2). This method could also be used in other human diseases such as neurological disorders 60, 61.

In this study, we also used WGCNA combination with PPI network to identify hub genes that link with HBV-associated HCC. Three clusters identified by PPI network from the most significant module by WGCNA were mainly involved in metabolism correlation pathways, cell cycle pathways and cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, which are closely related to HCC 33, 62. In Cluster 1, the expression levels of 10 genes were significantly correlated with OS of HBV-associated HCC patients by univariate Cox proportional hazards regression model and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, which had differences not only in the expression but also in survival. Therefore, seeking genes in the largest cluster, Cluster 1, for hub genes is more useful and precise for the generation and validation of prognostic signature by multivariable cox analysis.

Using clinical information, pathological classification and the expression of protective or risk genes could provide information for the diagnosis and prognosis in different types of cancer 63-65. Recently, some prediction models for risk assessment in HCC has been reported, such as 4-aminobutyrate aminotransferase (ABAT), alanine-glyoxylate aminotransferase (AGXT), aldehyde dehydrogenase 6 family member A1 (ALDH6A1), cytochrome P450 family 4 subfamily A polypeptide 11 (CYP4A11), D-amino-acid oxidase (DAO) and enoyl-CoA hydratase and 3-hydroxyacyl CoA dehydrogenase (EHHADH) 66-68. Several studies have identified prognostic signatures by combining multiple genes, which contained more than 6 genes, for HCC 66, 69, 70. Because many variables need to be controlled, these prognostic signatures are difficult to develop as diagnosis markers in the future. Li B et al recently identified a three-gene prognostic signature (UPB1, SOCS2 and RTN3) for HCC without considering the etiology of disease by using datasets from The Cancer Genome Atlas project (TCGA) 71. RTN3 is not a significant gene in HBV-associated HCC, which may limit its use in HBV-associated HCC [Table S1]. In the current study, we discovered a three-gene model (SPP2, CDC37L1, and ECHDC2) that contributes a specific prognostic signature for HBV-associated HCC, none of which were reported in previous prediction models. These three genes are specifically highly expressed in healthy liver tissue but lose their expression in HCC tissues (Data not shown). SPP2 is localized mainly in the extracellular region, which could inhibit the growth of HCC in vivo 59. CDC37L1 is localized mainly in cytoplasm and extracellular region, which participates in unfolded protein and heat shock protein binding 72, and has been considered as a promising marker in HCC. ECHDC2 is a mitochondrial-related gene, which takes part in the metabolic process and fatty acid biosynthesis 73.

These three hub genes may have protective roles in HBV-associated carcinogenesis mainly by involving drug metabolism-cytochrome P450, PPAR signaling pathway and many metabolic pathways, pathways of which are enriched in patients of the low-risk group by GSEA analysis. Previous studies revealed that abnormality of PPAR signaling and drug metabolism-cytochrome P450 pathway can be the characteristics of early stages of HCC 51, 52, 74. Reprogramming of metabolic pathways, such as fatty acid metabolism, is also associated with angiogenesis, cell adhesion and invasion of tumor tissue 75, 76. In patients in the low-risk group, higher expression levels of genes in these pathways, such as aldehyde dehydrogenase family, cytochrome P450 family, enoyl-CoA hydratase and 3-hydroxyacyl CoA dehydrogenase (EHHADH), help maintain good metabolic function in liver 77-79, which in turn might protect HCC patients from persistent drug toxicity in response to various drug treatments. Therefore, this three-gene prognostic signature may be a promising prognostic marker for HBV-associated HCC, which warrants further functional and mechanistic studies. It may also be beneficial to develop a commercial detection kit for diagnosis and prognosis prediction based on this three-gene prognosis signature.

Limitations exist in our study. Only the GSE14520 dataset was selected for this work, resulting in limited samples for the 3-gene signature model of prognosis. Also, little was known on the functions and mechanisms of these three genes in HBV-associated HCC. As a result, further validation studies of our model with independent larger cohorts and further characterization of the functions of these 3 genes in HBV-associated HCC are required in the future.

In conclusion, WGCNA analysis of differentially expressed genes acquired by RRA from 7 datasets following by multivariable Cox regression analysis identifies a three hub gene module (SPP2, CDC37L1, and ECHDC2) as a specific prognostic signature for HBV-associated HCC. The higher expression levels of these three genes may improve the prognosis of patients with HBV-associated HCC by influencing drug metabolism-cytochrome P450, PPAR signaling pathway and many other metabolic pathways.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary tables.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant No. 81372272, 81503083, 81520108029, 81101890 and 81560712]. We thank Dr. Haiyun Gan from Institute of Cancer Genetics, Columbia University for reviewing the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- GO

Gene ontology

- GSEA

Gene set enrichment analysis

- HRs

Hazard ratios

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- KEGG

Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes

- MCODE

Molecular complex detection

- MSigDB

Molecular signatures database

- OS

Overall survival

- PPI

Protein-protein interaction

- RNA-Seq

RNA sequencing

- RRA

Robust rank aggreg

- WGCNA

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis

- UVA Cox

univariate Cox

- MVA Cox

multivariate Cox

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- AFP

α-fetoprotein

- ALT

alanine transferase.

References

- 1.Chibon F. Cancer gene expression signatures - the rise and fall? Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:2000–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rung J, Brazma A. Reuse of public genome-wide gene expression data. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:89–99. doi: 10.1038/nrg3394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zucman-Rossi J, Villanueva A, Nault J, Llovet J. Genetic Landscape and Biomarkers of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1226–39.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoshida Y, Moeini A, Alsinet C, Kojima K, Villanueva A. Gene signatures in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Oncol. 2012;39:473–85. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mittal S, El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: consider the population. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47(Suppl):S2–6. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182872f29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan HL, Sung JJ. Hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis B virus. Semin Liver Dis. 2006;26:153–61. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-939753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertuccio P, Turati F, Carioli G, Rodriguez T, La Vecchia C, Malvezzi M. et al. Global trends and predictions in hepatocellular carcinoma mortality. J Hepatol. 2017;67:302–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brechot C. Pathogenesis of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma: old and new paradigms. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S56–61. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim BY, Choi DW, Woo SR, Park ER, Lee JG, Kim SH. et al. Recurrence-associated pathways in hepatitis B virus-positive hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:279. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1472-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee SY, Song KH, Koo I, Lee KH, Suh KS, Kim BY. Comparison of pathways associated with hepatitis B- and C-infected hepatocellular carcinoma using pathway-based class discrimination method. Genomics. 2012;99:347–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ueda T, Honda M, Horimoto K, Aburatani S, Saito S, Yamashita T. et al. Gene expression profiling of hepatitis B- and hepatitis C-related hepatocellular carcinoma using graphical Gaussian modeling. Genomics. 2013;101:238–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bair E, Tibshirani R. Semi-supervised methods to predict patient survival from gene expression data. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E108. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kolde R, Laur S, Adler P, Vilo J. Robust rank aggregation for gene list integration and meta-analysis. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:573–80. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang B, Horvath S. A general framework for weighted gene co-expression network analysis. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2005;4:Article17. doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Y, Chen L, Gu J, Zhang H, Yuan J, Lian Q. et al. Recurrently deregulated lncRNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14421. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulze K, Imbeaud S, Letouze E, Alexandrov LB, Calderaro J, Rebouissou S. et al. Exome sequencing of hepatocellular carcinomas identifies new mutational signatures and potential therapeutic targets. Nat Genet. 2015;47:505–11. doi: 10.1038/ng.3252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sung WK, Zheng H, Li S, Chen R, Liu X, Li Y. et al. Genome-wide survey of recurrent HBV integration in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44:765–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuan SX, Wang J, Yang F, Tao QF, Zhang J, Wang LL. et al. Long noncoding RNA DANCR increases stemness features of hepatocellular carcinoma by derepression of CTNNB1. Hepatology. 2016;63:499–511. doi: 10.1002/hep.27893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neumann O, Kesselmeier M, Geffers R, Pellegrino R, Radlwimmer B, Hoffmann K. et al. Methylome analysis and integrative profiling of human HCCs identify novel protumorigenic factors. Hepatology. 2012;56:1817–27. doi: 10.1002/hep.25870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roessler S, Jia HL, Budhu A, Forgues M, Ye QH, Lee JS. et al. A unique metastasis gene signature enables prediction of tumor relapse in early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Cancer Res. 2010;70:10202–12. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melis M, Diaz G, Kleiner DE, Zamboni F, Kabat J, Lai J. et al. Viral expression and molecular profiling in liver tissue versus microdissected hepatocytes in hepatitis B virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. J Transl Med. 2014;12:230. doi: 10.1186/s12967-014-0230-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–40. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wen Q, Yang Y, Chen X, Pan X, Han Q, Wang D. et al. Competing endogenous RNA screening based on lncRNA-mRNA co-expression profile in HBV-associated hepatocarcinogenesis. J Tradit Chin Med. 2017;37:510–21. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun X, Han Q, Luo H, Pan X, Ji Y, Yang Y. et al. Profiling analysis of long non-coding RNAs in early postnatal mouse hearts. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43485. doi: 10.1038/srep43485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:559. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saris CG, Horvath S, van Vught PW, van Es MA, Blauw HM, Fuller TF. et al. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis of the peripheral blood from Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis patients. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:405. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horvath S, Dong J. Geometric interpretation of gene coexpression network analysis. PLoS Comput Biol. 2008;4:e1000117. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Szklarczyk D, Morris JH, Cook H, Kuhn M, Wyder S, Simonovic M. et al. The STRING database in 2017: quality-controlled protein-protein association networks, made broadly accessible. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D362–D8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bader GD, Hogue CW. An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinformatics. 2003;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi H, Chen J, Li Y, Li G, Zhong R, Du D. et al. Identification of a six microRNA signature as a novel potential prognostic biomarker in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:21579–90. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang P, Cui J, Wen J, Guo Y, Zhang L, Chen X. Cisplatin induces HepG2 cell cycle arrest through targeting specific long noncoding RNAs and the p53 signaling pathway. Oncol Lett. 2016;12:4605–12. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.5288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fang F, Newport JW. Evidence that the G1-S and G2-M transitions are controlled by different cdc2 proteins in higher eukaryotes. Cell. 1991;66:731–42. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90117-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ding D, Lou X, Hua D, Yu W, Li L, Wang J. et al. Recurrent targeted genes of hepatitis B virus in the liver cancer genomes identified by a next-generation sequencing-based approach. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1003065. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rey S, Quintavalle C, Burmeister K, Calabrese D, Schlageter M, Quagliata L. et al. Liver damage and senescence increases in patients developing hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:1480–6. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang Y, Zheng J, Chen D, Li F, Wu W, Huang X. et al. Transcriptome profiling identifies a recurrent CRYL1-IFT88 chimeric transcript in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8:40693–704. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuan JM, Gao YT, Ong CN, Ross RK, Yu MC. Prediagnostic level of serum retinol in relation to reduced risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:482–90. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ishikawa T. Branched-chain amino acids to tyrosine ratio value as a potential prognostic factor for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2005–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i17.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cao LQ, Shao ZL, Liang HH, Zhang DW, Yang XW, Jiang XF. et al. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPARgamma) inhibits hepatoma cell growth via downregulation of SEPT2 expression. Cancer Lett. 2015;359:127–35. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Darpolor MM, Basu SS, Worth A, Nelson DS, Clarke-Katzenberg RH, Glickson JD. et al. The aspartate metabolism pathway is differentiable in human hepatocellular carcinoma: transcriptomics and (13) C-isotope based metabolomics. NMR Biomed. 2014;27:381–9. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang H, Ye J, Weng X, Liu F, He L, Zhou D. et al. Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals that the extracellular matrix receptor interaction contributes to the venous metastases of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Genet. 2015;208:482–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Corton JC, Anderson SP, Stauber A. Central role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in the actions of peroxisome proliferators. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2000;40:491–518. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.40.1.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ehsani Ardakani MJ, Safaei A, Arefi Oskouie A, Haghparast H, Haghazali M, Mohaghegh Shalmani H. et al. Evaluation of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma using Protein-Protein Interaction Networks. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2016;9:S14–S22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kanda T, Jiang X, Nakamura M, Haga Y, Sasaki R, Wu S. et al. Overexpression of the androgen receptor in human hepatoma cells and its effect on fatty acid metabolism. Oncol Lett. 2017;13:4481–6. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.5973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stine ZE, Walton ZE, Altman BJ, Hsieh AL, Dang CV. MYC, Metabolism, and Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:1024–39. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riaz SK, Iqbal Y, Malik MF. Diagnostic and therapeutic implications of the vascular endothelial growth factor family in cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:1677–82. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.5.1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Banday MZ, Sameer AS, Mir AH, Mokhdomi TA, Chowdri NA, Haq E. Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) -2, -7 and -9 promoter polymorphisms in colorectal cancer in ethnic Kashmiri population - A case-control study and a mini review. Gene. 2016;589:81–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2016.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alcantara MB, Dass CR. Regulation of MT1-MMP and MMP-2 by the serpin PEDF: a promising new target for metastatic cancer. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2013;31:487–94. doi: 10.1159/000350069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shay G, Lynch CC, Fingleton B. Moving targets: Emerging roles for MMPs in cancer progression and metastasis. Matrix Biol. 2015;44-46:200–6. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2015.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lei M. The MCM complex: its role in DNA replication and implications for cancer therapy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2005;5:365–80. doi: 10.2174/1568009054629654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yan T, Lu L, Xie C, Chen J, Peng X, Zhu L. et al. Severely Impaired and Dysregulated Cytochrome P450 Expression and Activities in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Implications for Personalized Treatment in Patients. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14:2874–86. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ramesh V, Ganesan K. Integrative functional genomic delineation of the cascades of transcriptional changes involved in hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Int J Cancer. 2016;139:1586–97. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dai M, Chen X, Mo S, Li J, Huang Z, Huang S. et al. Meta-signature LncRNAs serve as novel biomarkers for colorectal cancer: integrated bioinformatics analysis, experimental validation and diagnostic evaluation. Sci Rep. 2017;7:46572. doi: 10.1038/srep46572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang YY, Qi LN, Zhong JH, Qin HG, Ye JZ, Lu SD. et al. High expression of AKR1B10 predicts low risk of early tumor recurrence in patients with hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42199. doi: 10.1038/srep42199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xia H, Kong SN, Chen J, Shi M, Sekar K, Seshachalam VP. et al. MELK is an oncogenic kinase essential for early hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence. Cancer Lett. 2016;383:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang X, Yang XR, Sun C, Hu B, Sun YF, Huang XW. et al. Promyelocytic leukemia protein induces arsenic trioxide resistance through regulation of aldehyde dehydrogenase 3 family member A1 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2015;366:112–22. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mattu S, Fornari F, Quagliata L, Perra A, Angioni MM, Petrelli A. et al. The metabolic gene HAO2 is downregulated in hepatocellular carcinoma and predicts metastasis and poor survival. J Hepatol. 2016;64:891–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ho DW, Kai AK, Ng IO. TCGA whole-transcriptome sequencing data reveals significantly dysregulated genes and signaling pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Med. 2015;9:322–30. doi: 10.1007/s11684-015-0408-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lao L, Shen J, Tian H, Zhong G, Murray SS, Wang JC. Secreted phosphoprotein 24kD (Spp24) inhibits growth of hepatocellular carcinoma in vivo. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2017;51:51–5. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu G, Zhang F, Jiang Y, Hu Y, Gong Z, Liu S. et al. Integrating genome-wide association studies and gene expression data highlights dysregulated multiple sclerosis risk pathways. Mult Scler. 2017;23:205–12. doi: 10.1177/1352458516649038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu G, Zhang Y, Wang L, Xu J, Chen X, Bao Y. et al. Alzheimer's Disease rs11767557 Variant Regulates EPHA1 Gene Expression Specifically in Human Whole Blood. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;61:1077–88. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yu TT, Xu XM, Hu Y, Deng JJ, Ge W, Han NN. et al. Long noncoding RNAs in hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:7208–17. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i23.7208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van 't Veer LJ, Dai H, van de Vijver MJ, He YD, Hart AA, Mao M. et al. Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of breast cancer. Nature. 2002;415:530–6. doi: 10.1038/415530a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Beer DG, Kardia SL, Huang CC, Giordano TJ, Levin AM, Misek DE. et al. Gene-expression profiles predict survival of patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Nat Med. 2002;8:816–24. doi: 10.1038/nm733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dai J, Lu Y, Wang J, Yang L, Han Y, Wang Y. et al. A four-gene signature predicts survival in clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:82712–26. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kim SM, Leem SH, Chu IS, Park YY, Kim SC, Kim SB. et al. Sixty-five gene-based risk score classifier predicts overall survival in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2012;55:1443–52. doi: 10.1002/hep.24813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen P, Wang F, Feng J, Zhou R, Chang Y, Liu J. et al. Co-expression network analysis identified six hub genes in association with metastasis risk and prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8:48948–58. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang J, Chong CC, Chen GG, Lai PB. A Seven-microRNA Expression Signature Predicts Survival in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128628. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ao L, Song X, Li X, Tong M, Guo Y, Li J. et al. An individualized prognostic signature and multiomics distinction for early stage hepatocellular carcinoma patients with surgical resection. Oncotarget. 2016;7:24097–110. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Awan FM, Naz A, Obaid A, Ali A, Ahmad J, Anjum S. et al. Identification of Circulating Biomarker Candidates for Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC): An Integrated Prioritization Approach. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0138913. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li B, Feng W, Luo O, Xu T, Cao Y, Wu H. et al. Development and Validation of a Three-gene Prognostic Signature for Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2017;7:5517. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04811-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhou Y, Zeng Z, Zhang W, Xiong W, Li X, Zhang B. et al. Identification of candidate molecular markers of nasopharyngeal carcinoma by microarray analysis of subtracted cDNA libraries constructed by suppression subtractive hybridization. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2008;17:561–71. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e328305a0e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Alholle A, Brini AT, Gharanei S, Vaiyapuri S, Arrigoni E, Dallol A. et al. Functional epigenetic approach identifies frequently methylated genes in Ewing sarcoma. Epigenetics. 2013;8:1198–204. doi: 10.4161/epi.26266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cheng S, Prot JM, Leclerc E, Bois FY. Zonation related function and ubiquitination regulation in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells in dynamic vs. static culture conditions. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:54. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Monaco ME. Fatty acid metabolism in breast cancer subtypes. Oncotarget. 2017;8:29487–500. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Marin de Mas I, Aguilar E, Zodda E, Balcells C, Marin S, Dallmann G. et al. Model-driven discovery of long-chain fatty acid metabolic reprogramming in heterogeneous prostate cancer cells. PLoS Comput Biol. 2018;14:e1005914. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Matejcic M, Gunter MJ, Ferrari P. Alcohol metabolism and oesophageal cancer: a systematic review of the evidence. Carcinogenesis. 2017;38:859–72. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgx067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nebert DW, Russell DW. Clinical importance of the cytochromes P450. Lancet. 2002;360:1155–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhao S, Xu W, Jiang W, Yu W, Lin Y, Zhang T. et al. Regulation of cellular metabolism by protein lysine acetylation. Science. 2010;327:1000–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1179689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary tables.