Abstract

Mobile electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring is an emerging area that has received increasing attention in recent years, but still real-life validation for elderly residing in low and middle-income countries is scarce. We developed a wearable ECG monitor that is integrated with a self-designed wireless sensor for ECG signal acquisition. It is used with a native purposely designed smartphone application, based on machine learning techniques, for automated classification of captured ECG beats from aged people. When tested on 100 older adults, the monitoring system discriminated normal and abnormal ECG signals with a high degree of accuracy (97%), sensitivity (100%), and specificity (96.6%). With further verification, the system could be useful for detecting cardiac abnormalities in the home environment and contribute to prevention, early diagnosis, and effective treatment of cardiovascular diseases, while keeping costs down and increasing access to healthcare services for older persons.

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) have remained the leading cause of death globally during the last 15 years. An estimated 17.7 million people died from CVD in 2015, representing 31% of all global mortality. Of these deaths, approximately 6.9 million were in people aged 60 years and older, and over 75% occurred in low and middle-income countries (LMIC) [1, 2]. LMIC are more greatly affected than high-income countries [3–5], largely because people with low socioeconomic status have poor access to healthcare for early diagnosis and treatment of CVD [5]. An increasing urgency exists to tackle CVD in LMIC through effective strategies, guided and monitored by robust estimates of disease prevalence and burden [6]. Thus, technological innovations, including mobile and wireless technologies, are now being developed to improve prevention and control of CVD, and other aspects of healthcare, particularly for older people residing in LMIC [7–9].

The growing application of smartphone technology, due to decreasing costs and increased ease-of-use, combined with parallel advances in sensing technologies, is causing a shift from traditional clinic-based healthcare to real-time monitoring. This shift is supported by the development of mobile personal health monitor (PHM) systems, which are personalized, intelligent, reliable, and noninvasive [10, 11]. PHM systems could improve the quality of care, while reducing costs through timely detection [12–14].

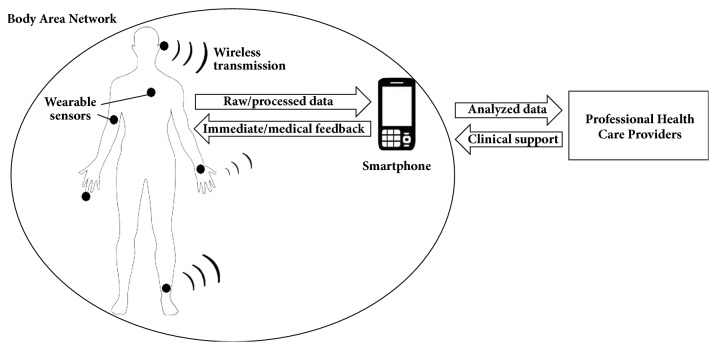

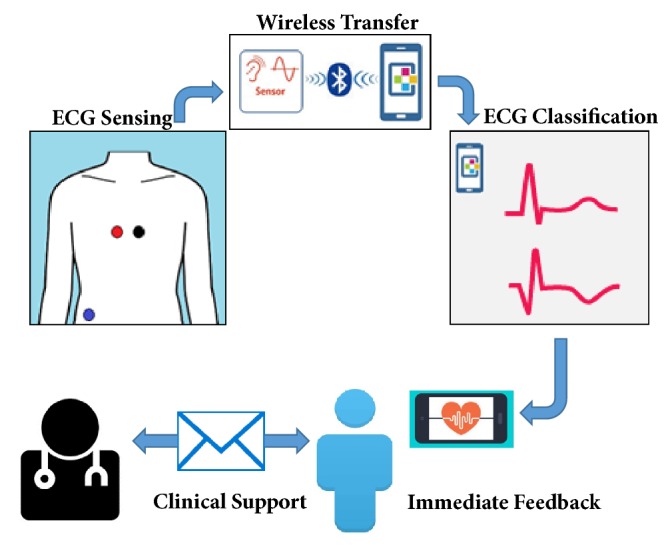

Mobile PHM systems typically consist of a Body Area Network—a set of wearable sensors with wireless data transfer and energy storage capability—integrated by a smartphone as the central processing unit (Figure 1). The physiological signals are processed in real-time by applying machine learning techniques, providing immediate feedback to the user. The data can also be made available to healthcare providers for medical feedback and clinical support [15–17].

Figure 1.

General architecture of a mobile personal health monitor system.

PHM systems that offer mobile electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring have received increasing attention in recent years [18–20]. ECG records are used for screening, diagnosis, and monitoring of several heart conditions from minor to life threatening. Hence, ECG monitoring is a critical and an essential part of healthcare delivery for older adults [17]. Therefore, PHM systems that incorporate ECG data would offer mobile physiological, diagnostic, prognostic, therapeutic, surveillance, and archival capabilities [18, 19] in a wide range of situations, including rural zones, areas lacking cardiologists, and population of solitary elderly, many of whom live alone in their own homes and are restricted physically [21].

However, although a number of PHM systems that collect ECG data have been developed, some of these do not include classification methods for automated detection of arrhythmias or other abnormalities. Among those validated, Kwon et al. proposed a smartphone-integrated ECG monitoring system that works opportunistically during natural smartphone use [22]. The system captured ECG reliably in target situations with a reasonable rate of data drop. Depari et al. developed a single-lead ECG tracing acquisition system based on a smartphone, with a purposely designed application to demodulate the audio signal and extract, plot, and store the ECG tracing [23]. Dinh designed a wearable unit for detecting and sending ECG signals wirelessly to a smartphone [24]. Yu et al. developed a wireless two-lead ECG sensor that transmitted data via Bluetooth and processed and displayed the ECG waveform on a smartphone, all with low power consumption for long-term monitoring [25].

Other PHM systems use commercial monitors or do not provide an intrinsic method for classify ECG signals. Lee et al. designed a wireless system for acquisition and classification of ECG beats integrated with a smartphone. Abnormal beats and other symptoms were diagnosed by cardiologists from results displayed on the screen. Accuracy of beat classification was 97.25% [26]. Miao et al. developed a wearable ECG monitoring system using a smartphone, with automated recognition of abnormal patterns via decision trees in a WEKA environment [27]. The system achieved a 2.6% discrimination ability [28]. Oresko et al. developed a smartphone-based application for real-time CVD detection, using a commercial ECG heart monitor and an adaptive artificial neural network (NN) algorithm for signal preprocessing and classification [29]. The system was trained using the MIT-BIH arrhythmia database [30] and retrained based on real ECG recordings, ultimately demonstrating classification accuracy of 93.32%. None of the aforementioned studies [22–26, 28, 29] reported considerations in software design to address end-user usability and acceptance of mobile PHM systems in older adults.

To improve on previous systems, it would be necessary to enhance the capture as well as the automated classification of ECG signals. We developed a complete mobile PHM system, integrated with a self-designed wireless sensor for ECG signal acquisition, and a native purposely designed smartphone application to be user-friendly to elderly, based on machine learning techniques, for automated classification of captured ECG beats. The signal sensing and transferring process uses a two-lead ECG sensor with Bluetooth technology and an artificial NN approach for identifying abnormal ECG patterns.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. The methodology of the proposed PHM system is presented in detail in Section 2; the experimental results for ECG signals acquisition, wireless transmission, and assessment of recognition accuracy are shown in Section 3; we conclude our study in Sections 4 and 5, with discussion, limitations, and perspective for further research.

2. Materials and Methods

The PHM system described in this report operates in five stages: sensing, transferring, classification, immediate feedback, and clinical support (Figure 2). The captured ECG tracings are transmitted and displayed in real-time on a smartphone screen. The presence or absence of arrhythmias, determined using machine learning analysis, is included and is shared via email with healthcare professionals for verification of abnormal ECG patterns.

Figure 2.

Framework of the mobile personal health monitor system.

2.1. ECG Sensor

The sensor design includes acquisition, amplification, filtering, digitalization, and transmission of ECG signals. Three identically sized electrodes and low frequency amplifiers are used to capture the signals and the coupling of impedances. The signal is filtered through low-pass and high-pass filters to improve the signal/noise ratio. The processed signal is then digitized and transmitted by an analog-to-digital converter and Bluetooth module embedded in a microcontroller unit. A 9V primary lithium battery with 1200 mAh capacity powers the ECG sensor.

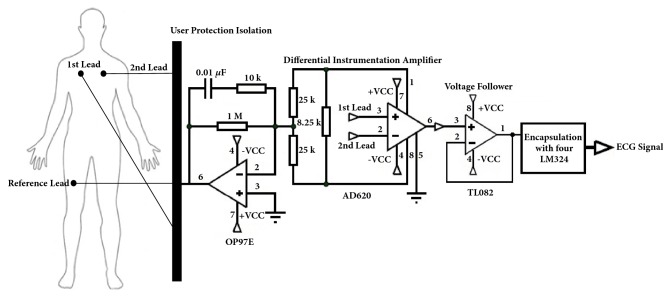

To acquire reliable ECG signals, two electrodes are attached to the chest as precordial leads V1 and V2 positioned in the fourth intercostal space to the right and left of the sternum, respectively, because incorrect positioning of the precordial electrodes changes the ECG significantly [31], and a reference electrode is placed far from these on the right leg (Figure 3). The reference electrode plays the role of driving the user's body to attenuate the common mode noise caused by external electromagnetic interference [32]. The analog input signal from two lead electrodes was initially amplified through an AD620 differential instrumentation amplifier [33]. Before the next amplifier stage, we coupled the impedance using a TL082 operational amplifier, configured as a voltage follower [34].

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the ECG amplifier circuit and electrode placement on the body.

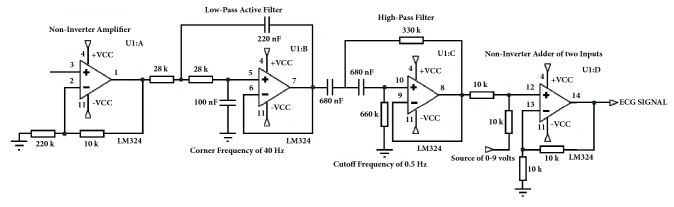

The current configuration uses an instrumental amplifier, based on an encapsulation with four LM324 operational amplifiers [35], to amplify the signal with a noninverter amplifier, then filter it, and add voltage (Figure 4). A low power OP97E operational amplifier [36] closes the circuit, protects the user from static charges, and suppresses voltage transients. Two LM324 operational amplifiers act as Butterworth filters, to generate an appropriate low-noise signal that fits within the input range of the analog-to-digital converter [37]. A low-pass active filter with a corner frequency of 40 Hz and a second-order high-pass filter with cutoff frequency of 0.5 Hz remove unnecessary frequency components of the ECG signal. Because the signal obtained consists of positive and negative parts, it was necessary to add a positive carrier signal. To recompose the signal, we used operational LM324 amplifiers as noninverter adders of the two inputs, fed by the ECG signal and a variable power source of 0–9 volts. This increases or decreases the carrier signal, as appropriate. A pair of equal resistances is added, one to the input of the analog signals and another from the inverter input of the operational amplifier to the circuit ground. Thus, the output signal has the same frequency, but with only positive voltage values, and is ready to be read by any microcontroller.

Figure 4.

Encapsulation with four LM324 operational amplifiers to amplify, filter, and add voltage to the ECG signal.

The Blend Micro of Read Bear Labs [38], which combines the Atmega32U4 microcontroller unit with a Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) module [39, 40], is used for microcontroller processing of the signal. Generic Access Profile (GAP) controls connections and advertising in BLE standard and determines how two devices interact with each other by assigning roles. The ECG sensor and smartphone are defined as peripheral and central devices, respectively. GAP sends advertising out as Advertising Data payload, which can contain up to 31 bytes of data and constantly transmits from the sensor to the smartphone. After a dedicated connection is established, the advertising process stops, and BLE uses Generic Attribute Profile (GATT) services and characteristics to communicate in both directions. This connection is exclusive, because a BLE peripheral only can be connected to one central device at a time.

Communication is established through a generic data protocol, Attribute Protocol, which is used to store services, characteristics, and related data in a simple lookup table. GATT transactions in BLE operate as a server/client relationship. The GATT server is the peripheral that holds the Attribute Protocol, and the GATT client (smartphone) sends requests to this server. All transactions are started by the master device, the smartphone, which receives responses from the slave device, the ECG sensor. A simple Universal Asynchronous Receiver Transmitter type interface [41] defines a custom service containing two specific characteristics for the channels of transmission and reception of the ECG signal.

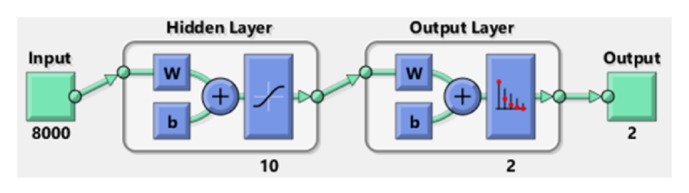

2.2. Neural Network Approach

We use a three-layered, feedforward NN approach, built through Matlab NN toolbox [42], for automated classification of acquired ECG tracings. A scaled conjugate gradient back-propagation algorithm with random weights/bias initialization is used for the training stage. The transfer functions are sigmoidal hyperbolic, logarithmic tangential, and lineal. Performance of the NN system was tested with a cross-entropy error function using the mean-squared error parameter, computed for differences between the actual outputs and the outputs obtained in each trained step. The training ended if the total sum of the squared errors was <0.01 or when 3000 epochs were reached. The target outputs for normal and abnormal ECG patterns were (0,1) and (1,0), respectively.

2.3. Data Processing

ECG data for training was obtained from a publicly available source, the Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt Diagnostic ECG Database [43]. This benchmark database contains 549 two-minute digitized ECG records of 290 subjects (mean age 57.2 y; 27.9% women) provided by the National Metrology Institute of Germany. The ECG data includes 15 simultaneously measured signals: the conventional 12 leads, plus 3 Frank Lead ECGs. Each signal is digitized at 1000 samples per second, with 16-bit resolution over a range of ±16 mV and 1 KHz sampling frequency.

We selected data from 268 subjects with clinical summaries available. These included a variety of diagnostic classes: 52 healthy controls, 148 myocardial infarctions, and 68 with other cardiac abnormalities. ECG beats were classified in normal and abnormal heartbeat patterns from ECG records reported as regular and irregular cardiac rhythm. Lead V1 was chosen for the analysis, because it has the highest ratio of atrial to ventricular signal amplitude and, therefore, offers more representative characteristics for identifying the common heart diseases [44, 45]. To avoid overfitting and improve the generalization capability of the NN approach, we added simulated ECG data with artificial corruption, using a Gaussian white-noise model [46], to generate 110 normal and 72 abnormal virtual ECG tracings. The global training dataset contained 8000 beats from all 450 records, for feature extraction of ECG patterns.

The trained NN system was tested on participants of the Maracaibo Aging Study [47], which has 2500 subjects ≥ 55 y of age. One hundred voluntary subjects (mean age 73.5 ± 11.8 y; 74% women) were recruited in the Institute for Biological Research of the University of Zulia, in Maracaibo, Venezuela. All 100 subjects had a previous ECG diagnostic performed by an expert cardiologist, and 13 were diagnosed with some type of cardiac arrhythmia. These ECG records were classified as abnormal and the rest as normal ECG patterns. Recruited participants had reasonable smartphone skills and were assertive about using new technologies. Each volunteer was instructed how to use the smartphone application and underwent 16-second ECG monitoring using the PHM system. ECG acquisitions were performed and supervised by medical staff. The ethical review board of the Institute of Cardiovascular Diseases of the University of Zulia approved the protocol. Informed consent was obtained from each subject or a close family member.

2.4. Software Development

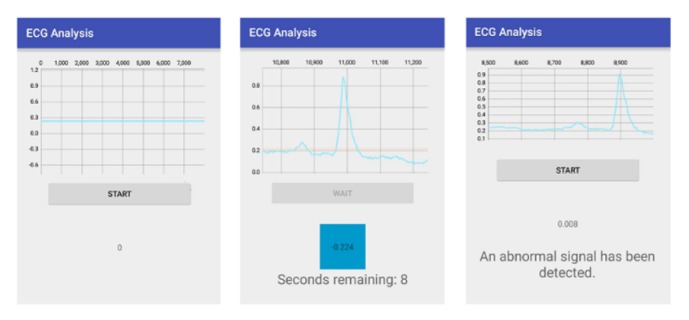

We use Matlab Compiler SDK to save the trained NN as a Matlab function into a shared library for use in an external framework [48]. The smartphone application for plotting the acquired ECG tracing on screen and for return NN output was developed in an Android Studio development environment. The Android Bluetooth serial port profile library [49] establishes the connection with the wearable ECG sensor. Android multithreading [50] allows the smartphone to maintain normal operations, while receiving real-time ECG signals. To make the Android application user-friendly to elderly subjects with reduced vision and manual dexterity, we use a simplified Graphic User Interface with a bright screen, large text and numbers, and simple input buttons with touchscreen technology, all of which have been proven to be efficient for older adults [51]. To provide accurate diagnostic and medical support, application settings include the option to sending screenshots of ECG signal and classification results via email to previously specified healthcare professionals. To assure privacy, reports forwarded to selected recipients lack personal identification, which is already associated with the source email address. The system can be configured to automatically send ECG profiles at the end of each monitoring period or only when abnormal ECG patterns are detected.

3. Results

3.1. Acquisition of ECG Signal

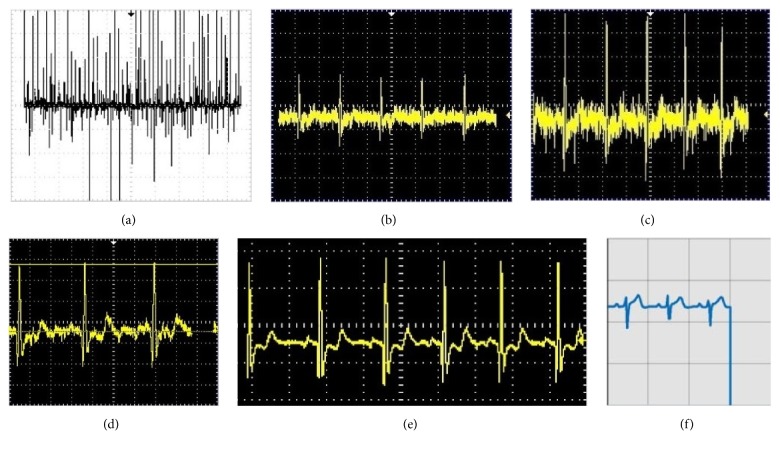

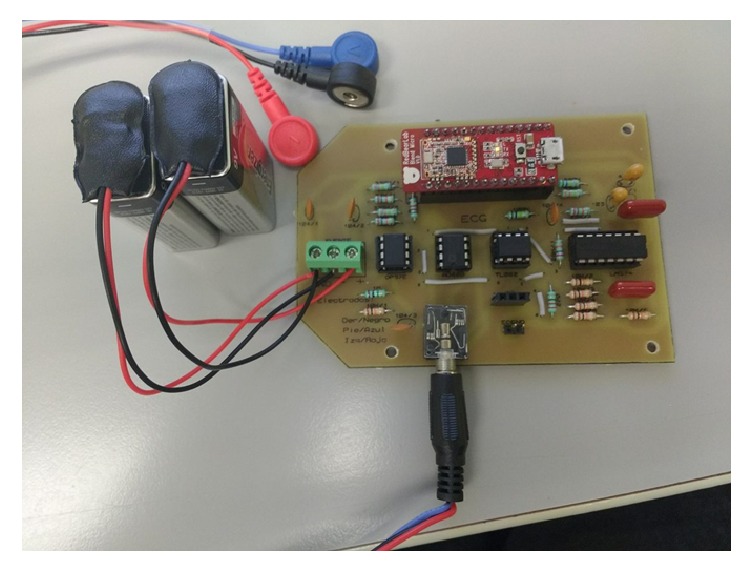

A prototype of the PHM system is shown in Figure 5, and the performance characteristics of the ECG sensor device are given in Table 1. Processing of the ECG tracing, from the first stage of amplification to display on the smartphone, includes (a) amplification by the AD620, (b) coupling of impedance through the TL082, (c) amplification through the LM324, (d) filtering through the low-pass filter, (e) filtering with the high-pass filter, and (f) digitalization and transmission of the positive ECG signal (Figure 6). The analytical process is displayed on the smartphone (Figure 7).

Figure 5.

Prototype of the self-designed ECG sensor device.

Table 1.

Performance summary of the ECG sensor device.

| Technology | Low-Power Microchip 8-bit AVR RISC-Based Microcontroller |

| Supply Voltage | 3.3 V |

| Input Impedance | 100 MΩ |

| Frequency Response | Range 0.1Hz and Internal 8MHz Calibrated Oscillator |

| Common Mode Rejection Ratio | >90dB |

| Gain | 45 |

| Sampling Rate | 9.6KHz |

| Data Bit-Width | 8 bits |

Figure 6.

ECG signal processing: (a) first stage of amplification; (b) impedance coupling; (c) second stage of amplification; (d) low-pass filtering; (e) high-pass filtering; (f) positive ECG signal on smartphone screen.

Figure 7.

Screenshots of ECG analysis process on smartphone.

3.2. ECG Classification

When the NN approach was trained on 450 records of the training dataset, the mean-squared error convergence goal (0.0052) was reached in 802 epochs. The best performance was obtained using 10 neurons in the hidden layer of the NN system (Figure 8). Overall classification accuracy in training stage was 97.3%. Correct classification was 92.6% for normal and 100% for abnormal ECG patterns.

Figure 8.

Neural network architecture with the best performance.

When performance of the trained NN approach was tested on real ECG tracings from the test dataset, classification accuracy was 97%. The results are shown in a confusion matrix, where each cell contains the number of ECG records classified for the corresponding combination of estimated and true outputs for normal and abnormal ECG patterns (Table 2).

Table 2.

Confusion matrix for classification of the test dataset.

| True output | ||

|---|---|---|

| Estimated output | Normal | Abnormal |

| Normal | 84 | 0 |

| Abnormal | 3 | 13 |

The total test performance was determined by evaluation metrics (Table 3): accuracy (ratio of the number of correctly classified ECG signals to the total number of ECG signals classified), sensitivity (rate of correctly classified abnormal ECG signals among all abnormal ECG signals), specificity (rate of correctly classified normal ECG signals among all normal ECG signals), and precision (rate of correctly classified abnormal ECG signals among all of detected abnormal ECG signals). These metrics are relevant to performance for medical diagnosis applications [52]. Finally, a posterior survey indicated that the majority of the participants found the smartphone application easy to use and considered the time spent learning how to use the mobile ECG monitoring system was reasonable.

Table 3.

Total test performance of the mobile PHM system.

| Evaluation metrics | Values (%) |

|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 100 |

| Specificity | 96.6 |

| Accuracy | 97 |

| Precision | 81.3 |

4. Discussion

Recent technological advances in integration and miniaturization of physical sensors and increasing computing capability of smartphones have enabled the development of mobile PHM systems as a cost-effective strategy to support healthcare that is focused on the consumer, transparency, convenience, and prevention [53]. Clinical studies reported high sensitivity and specificity at detecting atrial fibrillation [54] and other cardiac abnormalities using wireless mobile ECG devices [55–58]. The ability to provide pervasive heart monitoring to anyone at any time, through natural interactions between smartphone and user, overcomes constraints of place, time, and character and provides personalized information in a transparent form. Users can configure mobile PHM systems to their individual needs and preferences, taking into account age, gender, and ethnicity. Immediate feedback alerts the user of abnormal conditions or abrupt changes in near real-time, potentially improving outcomes. As a final point, clinicians can receive automated updates, providing structured CVD management while minimizing clinical visits.

On the other hand, results of a 2014 consumer survey, performed by PricewaterhouseCoopers Health Research Institute, showed that almost half of respondents were ready to have an ECG device attached to their smartphone, with results wirelessly sent to their physician [59]. Latest evidence from LMIC suggests that mobile PHM systems can improve lifestyle behaviors and healthcare management related to CVD, particularly for aged people and frail users [60].

Elderly should be the primary target of mobile ECG monitoring systems for several reasons. Mainly, because the population aged 65 and older is projected to be about 83.7 million in 2050 [61], worldwide epidemic of chronic diseases is strongly linked to population aging, and the leading contributors to disease burden in older people are CVD [6]. Nevertheless, mobile PHM systems remain in its nascent stages related to behavioral health and older adults [9].

While research in PHM systems have demonstrated feasibility and effectiveness across a variety of populations and health problems, studies generally exclude older adults or do not report significant age differences in responses to the interventions [9]. A possible explanation is the persistence of stereotypes that older adults are afraid, reluctant, and incompetent to use modern technology. Besides, seniors who may believe themselves incapable of learning to use new technologies perpetuate many of these stereotypes [62–64]. Therefore, usability and acceptance of mobile PHM by older adults is not only based on their healthcare requirements, but also on their perspective of technology. Since cognitive performance commonly declines with age, minimizing the complexity of smartphone applications and user-interactions could be key to the adoption of mobile PHM systems by elderly users and should be considered in stages of design and development [65].

In this sense, we developed a mobile PHM system for ECG monitoring and automated classification of heartbeat patterns to identify potential arrhythmias in elderly. The system combines a wearable wireless sensor, mobile technology, and machine learning techniques. Software design included specific characteristics aimed to improve usability and acceptance of older persons. User interface to display and classify ECG signals was simplified at one dedicated button to minimize the amount of steps to be memorized (Figure 7). Additionally, security mechanisms such as user identification and password were omitted to access smartphone application.

Our system has a number of advantages over previously developed mobile PHM systems for monitoring ECG signals, which do not report software design concept to address the user acceptability and acceptance issue in elderly [22–26, 28, 29], do not include automated classification [22–25], operate with commercial sensors [29], or do not provide internal methods for classifying arrhythmias [26, 28]. The prototype detected normal and abnormal ECG patterns in a group of older adults residing in a LMIC with a high degree of accuracy (97%), sensitivity (100%), and specificity (96.6%). Thus, our mobile ECG monitoring approach could be useful for detecting cardiac abnormalities in the home environment and contribute to prevention, early diagnosis, and effective treatment of CVD, while keeping costs down and increasing access to healthcare services for older persons.

However, the ECG monitoring and classification system described herein has several potential limitations. First, our system and most other mobile ECG monitors record a single-channel ECG signal, which provides more limited information than 12-lead ECG devices. Nevertheless, a recent study found good correlation between smartphone ECG and 12-lead ECG data, before and after antiarrhythmic drug therapy [66]. Second, despite high overall recognition, the precision of the NN classifier is only 81.3%, although false positive signals would be recognized by physician evaluation. Third, the system provides timely detection of abnormal ECG patterns for further diagnosis by healthcare professionals but does not identify specific types of cardiac disorders. Finally, the system was tested using a relatively small sample (n = 100) at a single center and primarily included Venezuelan females; thus, the system performance characteristics might not be generalizable to other user populations. Therefore, further studies are necessary to extend use of mobile ECG monitoring to other geographically diverse elderly populations as well as provide a better characterization of heart rhythm abnormalities.

5. Conclusions

The mobile ECG monitoring system described in this report provides near real-time data and automated classification of ECG signals from older adults. The machine learning classifier discriminates between normal and abnormal cardiac rhythms with high accuracy. With further development and verification, the system could provide a cost-effective strategy for primary diagnosis of potential arrhythmias and improve preventive healthcare, particularly in population of solitary elderly.

Acknowledgments

This research is financially supported by Grants DSA/103.5/15/11115 and PFCE/1585/17 from Secretaria de Educación Pública, México, and Grants 1R01AG036469-01A1 and R03AG054186 from the National Institute on Aging and Fogarty International Center.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.World health statistics 2017: Monitoring health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global Health Estimates 2015: Deaths by Cause, Age, Sex, by Country And by Region, 2000–2015. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wirtz V. J., Kaplan W. A., Kwan G. F., Laing R. O. Access to medications for cardiovascular diseases in low- and middle-income countries. Circulation. 2016;133(21):2076–2085. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.008722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen L., Williams J., Townsend N., et al. Socioeconomic status and non-communicable disease behavioural risk factors in low-income and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. The Lancet Global Health. 2017;5(3):e277–e289. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30058-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Cesare M., Khang Y.-H., Asaria P., et al. Inequalities in non-communicable diseases and effective responses. The Lancet. 2013;381(9866):585–597. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61851-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prince M. J., Wu F., Guo Y., et al. The burden of disease in older people and implications for health policy and practice. The Lancet. 2015;385(9967):549–562. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61347-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Free C., Phillips G., Watson L., et al. The Effectiveness of Mobile-Health Technologies to Improve Health Care Service Delivery Processes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS Medicine. 2013;10(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001363.e1001363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monitoring and Evaluating Digital Health Interventions: A Practical Guide to Conducting Research And Assessment. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuerbis A., Mulliken A., Muench F., A. Moore A., Gardner D. Older adults and mobile technology: Factors that enhance and inhibit utilization in the context of behavioral health. Mental Health and Addiction Research. 2017;2(2):1–11. doi: 10.15761/MHAR.1000136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.del Rosario M. B., Redmond S. J., Lovell N. H. Tracking the evolution of smartphone sensing for monitoring human movement. Sensors. 2015;15(8):18901–18933. doi: 10.3390/s150818901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mena L. J., Felix V. G., Ostos R., et al. Mobile personal health system for ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine. 2013;2013:1–13. doi: 10.1155/2013/598196.598196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng Y.-L., Ding X.-R., Poon C. C. Y., et al. Unobtrusive sensing and wearable devices for health informatics. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 2014;61(5):1538–1554. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2014.2309951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh M., Jain N. A Survey on Integrated Wireless Healthcare Framework for Continuous Physiological Monitoring. International Journal of Computer Applications. 2014;86(13):37–41. doi: 10.5120/15048-3416. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agu E., Pedersen P., Strong D., et al. The smartphone as a medical device: Assessing enablers, benefits and challenges. Proceedings of the 2013 10th Annual IEEE Communications Society Conference on Sensing and Communication in Wireless Networks (SECON); June 2013; New Orleans, LA, USA. pp. 76–80. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khan W. Z., Xiang Y., Aalsalem M. Y., Arshad Q. Mobile phone sensing systems: a survey. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials. 2013;15(1):402–427. doi: 10.1109/surv.2012.031412.00077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wac K. Smartphone as a personal, pervasive health informatics services platform: literature review. Yearbook of Medical Informatics. 2012;7:83–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baig M. M., Gholamhosseini H., Connolly M. J. A comprehensive survey of wearable and wireless ECG monitoring systems for older adults. Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing. 2013;51(5):485–495. doi: 10.1007/s11517-012-1021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennedy H. L. The evolution of ambulatory ECG monitoring. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases. 2013;56(2):127–132. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jain P. K., Tiwari A. K. Heart monitoring systems-A review. Computers in Biology and Medicine. 2014;54:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo S. L., Liu H. W., Si Q. J., Kong D. F., Guo F. S. The future of remote ECG monitoring systems. Journal of Geriatric Cardiology. 2016;13(6):528–530. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2016.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsukiyama T. In-home health monitoring system for solitary elderly. Procedia Computer Science. 2015;63:229–235. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwon S., Lee D., Kim J., et al. Sinabro: A smartphone-integrated opportunistic electrocardiogram monitoring system. Sensors. 2016;16(3, article no. 361) doi: 10.3390/s16030361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Depari A., Flammini A., Sisinni E., Vezzoli A. A wearable smartphone-based system for electrocardiogram acquisition. Proceedings of the 9th IEEE International Symposium on Medical Measurements and Applications, IEEE MeMeA 2014; June 2014; Lisboa, Portugal. IEEE; [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dinh A. Heart activity monitoring on smartphone. Proceedings of International Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Technology, ICBET 2011; June 2011; pp. 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu B., Xu L., Li Y. Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) based mobile electrocardiogram monitoring system. Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Information and Automation, ICIA 2012; June 2012; Shenyang, China. pp. 763–767. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee S.-Y., Hong J.-H., Hsieh C.-H., Liang M.-C., Chien S.-Y. C., Lin K.-H. Low-power wireless ECG acquisition and classification system for body sensor networks. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics. 2015;19(1):236–246. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2014.2310354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miao F., Cheng Y., He Y., He Q., Li Y. A wearable context-aware ECG monitoring system integrated with built-in kinematic sensors of the smartphone. Sensors. 2015;15(5):11465–11484. doi: 10.3390/s150511465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hall M., Frank E., Holmes G., Pfahringer B., Reutemann P., Witten I. H. The WEKA data mining software: an update. ACM SIGKDD Explorations Newsletter. 2009;11(1):10–18. doi: 10.1145/1656274.1656278. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oresko J. J., Jin Z., Cheng J., et al. A wearable smartphone-based platform for real-time cardiovascular disease detection via electrocardiogram processing. IEEE Transactions on Information Technology in Biomedicine. 2010;14(3):734–740. doi: 10.1109/TITB.2010.2047865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldberger A. L., Amaral L. A., Glass L., et al. PhysioBank, PhysioToolkit, and PhysioNet: components of a new research resource for complex physiologic signals. Circulation. 2000;101(23):E215–E220. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.101.23.e215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rajaganeshan R., Ludlam C. L., Francis D. P., Parasramka S. V., Sutton R. Accuracy in ECG lead placement among technicians, nurses, general physicians and cardiologists. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2008;62(1):65–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01390.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noro M., Anzai D., Wang J. Common-mode noise cancellation circuit for wearable ECG. Healthcare Technology Letters. 2017;4(2):64–67. doi: 10.1049/htl.2016.0083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang S. Z., Shan W., Song L. L. Principle and application of AD620 instrumentation amplifier. Microprocessors. 2008;4(4):38–40. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soliman A. M. Novel oscillators using current and voltage followers. Journal of The Franklin Institute. 1998;335(6):997–1007. doi: 10.1016/S0016-0032(97)00044-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Postolache O., Pereira J. D., Girão P. S. Wireless sensor network-based solution for environmental monitoring: Water quality assessment case study. IET Science, Measurement & Technology. 2014;8(6):610–616. doi: 10.1049/iet-smt.2013.0136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghafur N. D. A. Low cost electrocardiogram heart monitor kit [Ph.D. thesis] Johor Bahru, Malaysia: Universiti Teknologi Malaysia; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robertson D. G. E., Dowling J. J. Design and responses of Butterworth and critically damped digital filters. Journal of Electromyography & Kinesiology. 2003;13(6):569–573. doi: 10.1016/s1050-6411(03)00080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ang M. Combining the Blend micro with the Bluetooth low-energy module. https://www.packtpub.com/books/content/bluetooth-low-energy-blend-micro.

- 39.Gomez C., Oller J., Paradells J. Overview and evaluation of bluetooth low energy: an emerging low-power wireless technology. Sensors. 2012;12(9):11734–11753. doi: 10.3390/s120911734. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Townsend K. Introduction to Bluetooth Low Energy. https://cdn-learn.adafruit.com/downloads/pdf/introduction-to-bluetooth-low-energy.pdf.

- 41.Chun-Zhi H., Yin-shui X., Lun-yao W. A universal asynchronous receiver transmitter design. Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Communications and Control, ICECC 2011; September 2011; IEEE; pp. 691–694. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Demuth H. B., Beale M. H., De Jess O., Hagan M. T. Neural Network Design. USA: Martin Hagan; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bousseljot R., Kreiseler D., Schnabel A. Nutzung der EKG-Signaldatenbank CARDIODAT der PTB über das Internet. Biomedizinische Technik/Biomedical Engineering. 2009;40(s1):317–318. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mainardi L., Sornmo L., Cerutti S. Understanding atrial fibrillation: The signal processing contribution. San Rafael, CA, USA: Morgan Claypool Publishers; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramli A. B., Ahmad P. A. Correlation analysis for abnormal ECG signal features extraction. Proceedings of the 4th National Conference on Telecommunication Technology, NCTT 2003; January 2003; Shah Alam, Malaysia. IEEE; pp. 232–237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Szabó B. T., van der Vaart A. W., van Zanten J. H. Empirical Bayes scaling of Gaussian priors in the white noise model. Electronic Journal of Statistics. 2013;7:991–1018. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maestre G. E., Pino-Ramírez G., Molero A. E., et al. The Maracaibo Aging Study: Population and methodological issues. Neuroepidemiology. 2002;21(4):194–201. doi: 10.1159/000059524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. MathWorks, Compile MATLAB Functions, https://www.mathworks.com/help/compiler_sdk/matlab_code.html.

- 49.Yan M., Shi H. Smart living using Bluetooth-based Android smartphone. International Journal of Wireless & Mobile Networks. 2013;5(1):65–72. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maiya P., Kanade A., Majumdar R. Race detection for android applications. Proceedings of the 35th ACM SIGPLAN Conference on Programming Language Design and Implementation, PLDI 2014; June 2014; Edinburgh, UK. pp. 316–325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holzinger A. User-Centered Interface Design for Disabled and Elderly People: First Experiences with Designing a Patient Communication System (PACOSY) In: Miesenberger K., Klaus J, Zagler W., editors. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 2398. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2002. pp. 34–41. (Lecture Notes in Computer Science). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kiranyaz S., Ince T., Gabbouj M. Real-time patient-specific ECG classification by 1-D convolutional neural networks. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 2016;63(3):664–675. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2015.2468589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bruining N., Caiani E., Chronaki C., Guzik P., Van Der Velde E. Acquisition and analysis of cardiovascular signals on smartphones: Potential, pitfalls and perspectives: By the Task Force of the e-Cardiology Working Group of European Society of Cardiology. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2014;21(2s):4–13. doi: 10.1177/2047487314552604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wolf P. A., Abbott R. D., Kannel W. B. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham study. Stroke. 1991;22(8):983–988. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.22.8.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lau J. K., Lowres N., Neubeck L., et al. IPhone ECG application for community screening to detect silent atrial fibrillation: A novel technology to prevent stroke. International Journal of Cardiology. 2013;165(1):193–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.01.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lowres N., Neubeck L., Salkeld G., et al. Feasibility and cost-effectiveness of stroke prevention through community screening for atrial fibrillation using iPhone ECG in pharmacies: The SEARCH-AF study. Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2014;111(6):1167–1176. doi: 10.1160/TH14-03-0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Haberman Z. C., Jahn R. T., Bose R., et al. Wireless smartphone ECG enables large-scale screening in diverse populations. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology. 2015;26(5):520–526. doi: 10.1111/jce.12634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Orchard J., Lowres N., Freedman S. B., et al. Screening for atrial fibrillation during influenza vaccinations by primary care nurses using a smartphone electrocardiograph (iECG): A feasibility study. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2016;23(2):13–20. doi: 10.1177/2047487316670255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.New Health Economy Healthcare’s new entrants: Who will be the industry’s Amazon.com? USA: PwC Health Research Institute; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Piette J. D., List J., Rana G. K., Townsend W., Striplin D., Heisler M. Mobile health devices as tools for worldwide cardiovascular risk reduction and disease management. Circulation. 2015;132(21):2012–2027. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.008723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ortman J. M., Velkoff V. A., Hogan H., An aging H. An Aging Nation: The Older Population in The United States. Suitland, MD, USA: United States Census Bureau; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Durick J., Robertson T., Brereton M., Vetere F., Nansen B. Dispelling ageing myths in technology design. Proceedings of the 25th Australian Computer-Human Interaction Conference: Augmentation, Application, Innovation, Collaboration, OzCHI 2013; November 2013; Adelaide, Australia. pp. 467–476. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McCann R. M., Keaton S. A. A Cross Cultural Investigation of Age Stereotypes and Communication Perceptions of Older and Younger Workers in the USA and Thailand. Educational Gerontology. 2013;39(5):326–341. doi: 10.1080/03601277.2012.700822. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barnard Y., Bradley M. D., Hodgson F., Lloyd A. D. Learning to use new technologies by older adults: perceived difficulties, experimentation behaviour and usability. Computers in Human Behavior. 2013;29(4):1715–1724. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lv Z., Xia F., Wu G., Yao L., Chen Z. iCare: A Mobile Health Monitoring System for the Elderly. Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Green Computing and Communications; December 2010; Hangzhou, China. pp. 699–705. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chung E. H., Guise K. D. QTC intervals can be assessed with the AliveCor heart monitor in patients on dofetilide for atrial fibrillation. Journal of Electrocardiology. 2015;48(1):8–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.