Abstract

Background:

Since the increase in some tubular damage biomarkers can be observed at the early stage of diabetic nephropathy, even in the absence of albuminuria, we aimed to investigate if urinary albumin is superior than tubular damage marker, such as serum retinol-binding protein 4 (RBP4), in predicting renal function decline (defined as estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] <60 mL/min/1.73 m2) in the cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D).

Materials and Methods:

A total of 106 sedentary T2D patients (mean [± standard deviation] age 64.9 [±6.6] years) were included in this cross-sectional study. Anthropometric and biochemical parameters (fasting glucose, glycated hemoglobin [HbA1c], lipid parameters, creatinine, RBP4, high sensitivity C-reactive protein [hsCRP], urinary albumin excretion [UAE]), as well as blood pressure were obtained.

Results:

HsCRP (odds ratio [OR] =0.754, 95% confidence interval [CI] (0.603–0.942), P = 0.013) and RBP4 (OR = 0.873, 95% CI [0.824–0.926], P < 0.001) were independent predictors of eGFR decline. Moreover, although RBP4 and UAE as single diagnostic parameters of renal impairment showed excellent clinical accuracy (area under the curve [AUC] = 0.900 and AUC = 0.940, respectively), the Model which included body mass index, HbA1c, triglycerides, hsCRP, and RBP4 showed statistically same accuracy as UAE, when UAE was used as a single parameter (AUC = 0.932 vs. AUC = 0.940, respectively; P for AUC difference = 0.759). As well, the Model had higher sensitivity and specificity (92% and 90%, respectively) than single predictors, RBP4, and UAE.

Conclusion:

Although serum RBP4 showed excellent clinical accuracy, just like UAE, a combination of markers of tubular damage, inflammation, and traditional markers has the higher sensitivity and specificity than UAE alone for prediction renal impairment in patients with T2D.

Keywords: Albuminuria, diabetic nephropathy, inflammation, retinol-binding protein 4

INTRODUCTION

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) has been widely recognized as a common complication of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D), which may further progress into end-stage renal disease and premature mortality.[1]

Oxidative stress and increased inflammation are considered as key determinants of DN.[2,3,4] Due to increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) and inflammatory cytokines production, glomerular filtration membrane becomes permeable for plasma proteins, resulting in albuminuria, a hallmark of early loss of renal function.[1,5] However, not always renal impairment is accompanied with albuminuria since it is known that DN is observed among normoalbuminuric patients with T2D, as well.[1,6] In addition, in some cases with T2D, microalbuminuria (30–300 mg/24 h) can have transient character, especially along with improvement of glycemic or blood pressure control.[7] All of this may in part explain why changes in albuminuria are now considered as complementary rather than obligatory manifestations of DN.[1] In addition, not only the dysfunction of glomeruli but also the impairment of renal tubules also plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of DN.[1] As well, the increase in some of the tubular damage biomarkers has been observed at the early stage of DN, even in the absence of albuminuria, thus making them specific and sensitive markers of DN.[1]

Retinol-binding protein 4 (RBP4) has been widely explored as adipokine, closely related to cardiometabolic indices.[8,9,10,11] Furthermore, due to its low molecular weight (21 kDa), it is freely filtered through the glomeruli and then almost completely reabsorbed in the proximal tubuls, which makes this protein as useful biomarker of tubular renal impairment. Namely, a significant rise of this biomarker has been observed in the end-stage renal disease,[12] which was decreased after kidney transplantation.[13] As well, serum RBP4 levels were associated with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), as well as positively correlated with changes in serum creatinine, confirming its association with renal function.[13]

In order to get better insight into the pathophysiological mechanisms of renal function decline, we aimed to examine markers of glomerular damage (i.e., urinary albumin), markers of tubular damage (i.e., serum RBP4), and inflammation markers (i.e., serum high sensitivity C-reactive protein level [hsCRP]) in patients with T2D. Furthermore, we aimed to investigate if urinary albumin is superior than tubular damage, inflammation, and some traditional markers in predicting renal function impairment in the cohort of patients with T2D.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

The current cross-sectional study derived from our previous works investigating the utility of cardiometabolic, inflammation, and oxidative stress markers in individuals with T2D.[14,15,16,17]

The study enrolled a total of 106 patients with T2D (mean age 64.9 ± 6.6 years, of them 61.3% females). All patients with T2D were consecutively recruited by the endocrinologist in the Center for Laboratory Diagnostics of the Primary Health Care Center in Podgorica, Montenegro, for their regular checkup in a period from October 2012 to May 2016.

Participants that were included in the study were patients with T2D without acute inflammatory disease, or urinary infection and/or hematuria. Diabetes cases were defined as described in our previous reports.[14,15,16,17]

Exclusion criteria from the current investigation were participants with diabetes mellitus type 1, with eGFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2, patients on chronic dialysis, with kidney transplantation, renal disease other than DN, diseases other than diabetes which induce proteinuria (e.g., vasculitis and amyloidosis), hsCRP >10 mg/L, those with a recent (6 months) history of acute myocardial infarction or stroke, carcinoma, pregnancy, and with history of alcohol abuse (i.e., ethanol consumption >20 g/day). All the examinees signed informed consent. Ethical Committee of Primary Health Care Center in Podgorica, Montenegro (number 317/2) approved the study protocol, and the investigation was carried out in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Anthropometric measurements

Basic anthropometric measurements were obtained, as described previously.[18]

Biochemical analyses

After at least 8 h of an overnight fasting, cubital venous sample blood (10 mL) was collected from each participant for biochemical analyses (fasting glucose, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides [TG], creatinine, glycated hemoglobin [HbA1c], hsCRP, and RBP4 levels), as described elsewhere.[14,18] Examinees were requested to provide two blood samples, one for whole blood in K2 EDTA for HbA1c determination and the other for serum extraction. Patients were also asked to provide 24 h urine sample. Rate of urinary albumin excretion (UAE) <30 mg/24 h was considered as normoalbuminuria; UAE within the range 30–300 mg/24 h was considered as microalbuminuria, while UAE rate ≥300 mg/24 h was regarded as macroalbuminuria. All the examinees were instructed on how to collect 24 h urine and asked to store the urine on cold (4°C).

Blood pressure was measured as described previously.[18]

Glomerular filtration rate was estimated by using creatinine in the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study equation (eGFRMDRD).[14] Renal function decline is defined as eGFRMDRD <60 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with MedCalc Version 12.5 (Mariakerke, Belgium) and SPSS® Statistics version 22 (Chicago, Illinois, USA) statistical softwares for Windows.

The distributions of variables were checked by Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Differences in clinical parameters between individuals were analyzed by Student's t-test for normally and log-normally distributed variables and by Mann–Whitney U-test for skewed distribution. Bivariate correlation between eGFRMDRD and other clinical parameters were analyzed by nonparametric Spearman correlation analysis.

Logistic regression analysis was used to elucidate the association between eGFRMDRD and other clinical parameters. The dependent variable was eGFRMDRD coded as 0 for eGFRMDRD <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and coded as 1 for eGFRMDRD ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Since we aimed to get better insight into the pathophysiological mechanisms of renal function decline in patients with T2D, we included marker of glomerular damage (i.e., UAE), marker of tubular damage (i.e., serum RBP4), and inflammation marker (i.e., serum hsCRP). In addition, we included traditional risk factors such as body mass index (BMI), HbA1c, and TG. Therefore, independent variables were BMI, HbA1c, TG, hsCRP, RBP4, and UAE (all continuous). Those continuous variables which had P < 0.05 when testing bivariate correlations with eGFRMDRD were included in univariate and further multivariate logistic regression analysis. Because they entered the equation for GFR calculation, age and creatinine were excluded from logistic regression analysis. To examine tested independent variables, independent predictions on eGFRMDRD multivariate logistic regression analysis were employed. The explained variation in eGFRMDRD was given by Nagelkerke R2 value. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to test the diagnostic performance of each independent variable and the Model to discriminate patients that suffered from renal function decline from those that did not have it. Differences between curve areas for UAE and the Model were also tested.

Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed continuous variables, as geometrical mean (95% confidence interval [CI]) for log- normally distributed variables, median (interquartile range), and as absolute frequencies for categorical variables.[19] All tests were considered significant at the probability level P < 0.05.

RESULTS

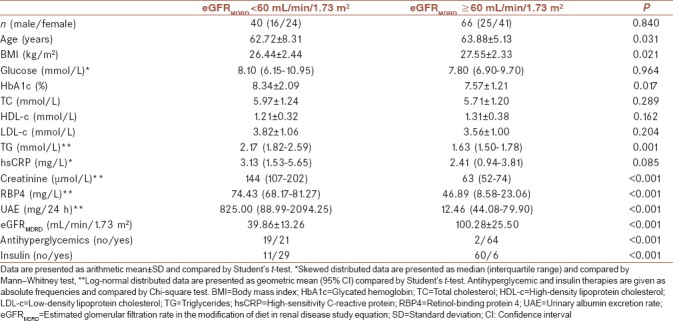

Table 1 shows the biochemical parameters in diabetic patients with renal decline (eGFRMDRD <60 mL/min/1.73 m2) and those that did not have it (eGFRMDRD ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2). Unequal distribution of patients taking antihyperglycemic or insulin therapies was established among groups. Patients with eGFRMDRD ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 were older and had higher BMI than those with eGFRMDRD <60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Furthermore, HbA1c, TG, creatinine, RBP4, and UEA concentrations were significantly higher among patients with eGFRMDRD <60 mL/min/1.73 m2. No other significant differences in clinical parameters were present between these two groups [Table 1].

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with diabetes according to estimated glomerular filtration rate

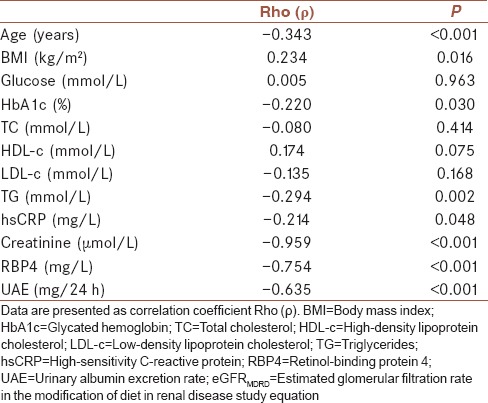

Spearman's correlation analyses were performed to test the associations between eGFRMDRD and other clinical parameters. Estimated GFRMDRD was significantly negatively correlated with age, TG, hsCRP, creatinine, RBP4, UAE, and positively correlated with BMI [Table 2].

Table 2.

Spearman's correlation analysis between eGFRMDRD and clinical parameters in patients with diabetes

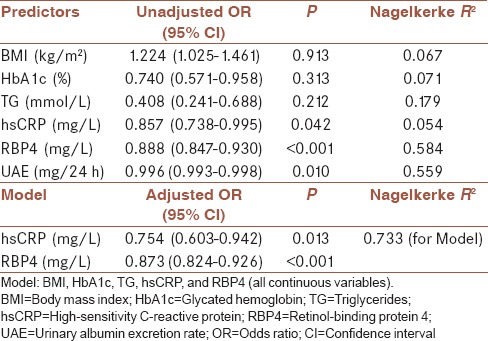

Table 3 summarizes results of logistic regression analysis applied to examine the associations of parameters significantly correlated with eGFRMDRD such as BMI, HBA1c, TG, hsCRP, RBP4, and UAE as independent variables (predictors) on eGFRMDRD as dependent variable. Age and creatinine were excluded from further analysis because they were used for eGFRMDRD calculation. Predictors were unadjusted and adjusted for other parameters and tested by univariate and multivariate analysis, respectively. In order to test if RBP4 together with other routinely determined parameters could be as good indicator of renal function as UAE, the latter was tested only in univariate analysis and it did not enter the Model like all the other parameters. HsCRP, RBP4, and UAE showed significant odds ratio (OR) in univariate logistic regression [Table 3]. As hsCRP rose for 1 mg/L, RBP for 1 mg/L, and UAE for 1 mg/24 h, probability for eGFRMDRD ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 decreased for 14.3%, 11.2%, and 0.4%, respectively. Nagelkerke R2 showed that each predictor in univariate analysis such as hsCRP, RBP4, and UAE could explain the variation in eGFRMDRD by 5.4%, 58.4%, and 55.9%, respectively. Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that only hsCRP and RBP4 kept independent prediction on eGFRMDRD [Model, Table 3. As hsCRP rose for 1 mg/L and RBP4 for 1 mg/L, the probability for eGFRMDRD ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 decreased for 24.6% and 12.7%, respectively. Adjusted R2 for the Model was 0.733, which means that even 73.3% of variation in eGFRMDRD could be explained with this Model [Table 3].

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis for clinical parameters predicting estimated glomerular filtration rate in patients with diabetes

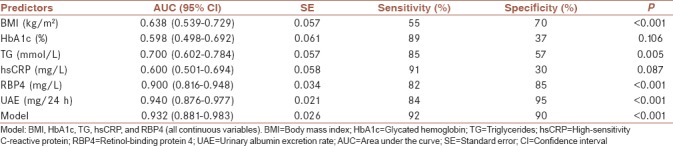

ROC analysis was used to discriminate patients with renal function decline from those who did not have it [Table 4]. The calculated AUC for BMI, HbA1c, TG, and hsCRP were ranking from 0.600 to 0.700 indicated that the clinical accuracy of each diagnostic parameter was low according to Swets.[20] On the contrary to these single predictors, RBP4 and UAE as single diagnostic parameters of renal impairment showed excellent clinical accuracy (AUC = 0.900 and AUC = 0.940, respectively) [Table 4]. Furthermore, the same was established for the Model which included BMI, HbA1c, TG, hsCRP, and RBP4 (continuous variables). The calculated AUC for the Model was 0.932 which suggested statistically same accuracy as UAE, when UAE was used as a single parameter [Figure 1]. Accordingly, the difference between areas was 0.008, SE = 0.026, 95% CI (−0.043–0.059) and P = 0.759. As well, the Model had higher sensitivity and specificity (92% and 90%, respectively) than single predictors (i.e., RBP4 and UAE) [Table 4 and Figure 1].

Table 4.

Receiver operating characteristic analysis for single parameters and the Model discriminatory abilities regarding renal function decline in patients with diabetes

Figure 1.

Discriminatory abilities of UAE as a single parameter and the Model regarding renal function decline. Model: BMI, HbA1c, TG, hsCRP, and RBP4 (all continuous variables). BMI = Body mass index; HbA1c = Glycated hemoglobin; TG = Triglycerides; hsCRP = High-sensitivity C-reactive protein; RBP4 = Retinol-binding protein 4; UAE = Urinary albumin excretion rate

DISCUSSION

The main finding of the current study is that tubular damage marker such as serum RBP4 as single diagnostic parameter of renal impairment showed excellent clinical accuracy, just like UAE (AUC = 0.900 and AUC = 0.940, respectively) [Table 4]. Furthermore, we have shown that serum RBP4, hsCRP and some routinely determined parameters, could be as good indicators of renal function decline (defined as eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2) as UAE.

Even though albuminuria has been considered as the gold standard biomarker for DN onset and progression, it lacks specificity for diagnosing disease progression (i.e., when UAE is 30–300 mg/24 h), as well as sensitivity, since DN can often progress even without albuminuria.[7,21] Hence, the quest for a better biomarkers with high sensitivity and specificity for early detection of DN is needed.

Since renal proximal tubular injury may occur before a reduction of GFR, we examined the utility of tubular biomarker, such as serum RBP4, in comparison with glomerular biomarkers, such as urinary albumin. Previous study by Mahfouz et al.[22] showed that RBP4 was more specific (90% specificity) than albumin-to-creatinine ratio for discriminating DN onset (72% specificity), suggesting that RBP4 may serve as an efficient diagnostic tool for clinical monitoring of kidney disease progression. However, our study reported that both of those biomarkers had excellent clinical accuracy for eGFR decline prediction. Several previous studies also reported elevated serum RBP4 levels in kidney disease[12,13,23,24] but did not make a comparison between those two biomarkers.

Oxidative stress and increased inflammation play a key role in DN development.[1,2] Chronic hyperglycemia enhances ROS production which causes the damage of the glomerular filtration barrier integrity, leading to albumin leakage, which can with ROS in the tubular ultrafiltrate further activate a variety of aberrant signaling pathways to cause overall renal function deterioration.[1] Increased activation of different signaling mediators such as transcription factors, inflammatory agents, and cytokines can compromise renal hemodynamics and increase glomerular extracellular matrix accumulation, thus further leading to interstitial fibrosis and glomerulosclerosis to eventual end-stage renal disease.[25]

Indeed, individuals with DN have increased low-grade inflammation for years before renal impairment can become clinically detectable.[21]

Multivariate logistic regression analysis in the current study showed that both hsCRP and RBP4 kept independent prediction on eGFRMDRD [Model, Table 3]. As hsCRP rose for 1 mg/L and RBP4 for 1 mg/L, probability for eGFRMDRD ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 decreased for 24.6% and 12.7%, respectively.

Pro-inflammatory cytokines are considered as determining factors in the development of microvascular diabetic complications, acting through nuclear transcription factor-kappa B (NF-κB) signaling hsCRP pathway.[26]

In line with our results, previous studies also reported high hsCRP in patients with DN.[26,27] Furthermore, earlier studies reported the utility of some other parameters such as cystatin C, for estimation of eGFR decline, suggesting its high diagnostic accuracy for screening of DN.[28]

In our study, to seek for the panel of parameters that might display the best specificity and sensitivity for discrimination of patients with renal function decline from those who did not have it, ROC analysis was used [Table 4]. Model which included RBP4, hsCRP, gender, BMI, HbA1c and TG, suggested statistically same accuracy as UAE, when UAE was used as a single parameter (AUC = 0.932 vs. AUC = 940, respectively; p for AUC diff erence = 0.759) [Table 4 and Figure 1]. Of note, the Model had higher sensitivity and specificity (92% and 90%, respectively) than single predictors RBP4 and UAE [Table 4], suggesting that other traditional markers should not be underestimated when examining diabetic kidney disease.[29,30]

The limitations of our study are cross-sectional design and small sample size. However, in addition to urinary albumin we examined a broad panel of biomarkers, such as marker of tubular damage but also inflammation and several well-known traditional markers.

CONCLUSION

The novel finding of the current study is that even though that tubular damage marker such as serum RBP4 as single diagnostic parameter of renal impairment showed excellent clinical accuracy, just like UAE, a combination of markers of tubular damage, inflammation markers, and traditional markers has the higher sensitivity and specificity than urinary albumin alone. Given that the early prediction of the onset of renal function decline is of urgent need to prevent further possible complications, the quest for more biomarkers with higher sensitivity and specificity is of great clinical importance.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was financially supported in part by a grant from the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development, Republic of Serbia (Project number 175035).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fiseha T, Tamir Z. Urinary markers of tubular injury in early diabetic nephropathy. Int J Nephrol 2016. 2016:4647685. doi: 10.1155/2016/4647685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miranda-Díaz AG, Pazarín-Villaseñor L, Yanowsky-Escatell FG, Andrade-Sierra J. Oxidative stress in diabetic nephropathy with early chronic kidney disease. J Diabetes Res 2016. 2016:7047238. doi: 10.1155/2016/7047238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saif-Elnasr M, Ibrahim IM, Alkady MM. Role of Vitamin D on glycemic control and oxidative stress in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Res Med Sci. 2017;22:22. doi: 10.4103/1735-1995.200278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Papaetis GS, Papakyriakou P, Panagiotou TN. Central obesity, type 2 diabetes and insulin: Exploring a pathway full of thorns. Arch Med Sci. 2015;11:463–82. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2015.52350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nasri H, Rafieian-Kopaei M. Diabetes mellitus and renal failure: Prevention and management. J Res Med Sci. 2015;20:1112–20. doi: 10.4103/1735-1995.172845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Porrini E, Ruggenenti P, Mogensen CE, Barlovic DP, Praga M, Cruzado JM, et al. Non-proteinuric pathways in loss of renal function in patients with type 2 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3:382–91. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glassock RJ. Control of albuminuria in overt diabetic nephropathy: Durability counts. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31:1371–3. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tabesh M, Noroozi A, Amini M, Feizi A, Saraf-Bank S, Zare M, et al. Association of retinol-binding protein 4 with metabolic syndrome in first-degree relatives of type 2 diabetic patients. J Res Med Sci. 2017;22:28. doi: 10.4103/1735-1995.200270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klisić A, Kavarić N, Bjelaković B, Soldatović I, Martinović M, Kotur-Stevuljević J, et al. The association between retinol-binding protein 4 and cardiovascular risk score is mediated by waist circumference in overweight/Obese adolescent girls. Acta Clin Croat. 2017;56:92–8. doi: 10.20471/acc.2017.56.01.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen D, Huang X, Lu S, Deng H, Gan H, Du X, et al. RBP4/Lp-PLA2/Netrin-1 signaling regulation of cognitive dysfunction in diabetic nephropathy complicated with silent cerebral infarction. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2017;125:547–53. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-109099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klisic A, Kotur-Stevuljevic J, Kavaric N, Matic M. Relationship between cystatin C, retinol-binding protein 4 and Framingham risk score in healthy postmenopausal women. Arch Iran Med. 2016;19:845–51. doi: 10.1002/eat.20869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubinow KB, Henderson CM, Robinson-Cohen C, Himmelfarb J, de Boer IH, Vaisar T, et al. Kidney function is associated with an altered protein composition of high-density lipoprotein. Kidney Int. 2017;92:1526–35. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang WX, Zhou W, Zhang ZM, Zhang ZQ, He JF, Shi BY, et al. Decreased retinol-binding protein 4 in the sera of patients with end-stage renal disease after kidney transplantation. Genet Mol Res. 2014;13:8126–34. doi: 10.4238/2014.October.7.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klisic A, Kavaric N, Jovanovic M, Zvrko E, Skerovic V, Scepanovic A, et al. Association between unfavorable lipid profile and glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Res Med Sci. 2017;22:122. doi: 10.4103/jrms.JRMS_284_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klisic A, Isakovic A, Kocic G, Kavaric N, Jovanovic M, Zvrko E, et al. Relationship between oxidative stress, inflammation and dyslipidemia with fatty liver index in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2017;125:1–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-118667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kavaric N, Klisic A, Ninic A. Are visceral adiposity index and lipid accumulation product reliable indices for metabolic disturbances in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus? J Clin Lab Anal. 2018;32:e22283. doi: 10.1002/jcla.22283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klisic A, Kocic G, Kavaric N, Jovanovic M, Stanisic V, Ninic A, et al. Xanthine oxidase and uric acid as independent predictors of albuminuria in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2. Clin Exp Med. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s10238-017-0483-0. DOI: 10.1007/s10238-017-0483-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klisic A, Kavaric N, Jovanovic M, Soldatovic I, Gligorovic-Barhanovic N, Kotur-Stevuljevic J, et al. Bioavailable testosterone is independently associated with fatty liver index in postmenopausal women. Arch Med Sci. 2017;13:1188–96. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2017.68972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bland JM, Altman DG. Transformations, means, and confidence intervals. BMJ. 1996;312:1079. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7038.1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swets JA. Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. Science. 1988;240:1285–93. doi: 10.1126/science.3287615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Rubeaan K, Siddiqui K, Al-Ghonaim MA, Youssef AM, Al-Sharqawi AH, AlNaqeb D, et al. Assessment of the diagnostic value of different biomarkers in relation to various stages of diabetic nephropathy in type 2 diabetic patients. Sci Rep. 2017;7:2684. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02421-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahfouz MH, Assiri AM, Mukhtar MH. Assessment of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) and retinol-binding protein 4 (RBP4) in type 2 diabetic patients with nephropathy. Biomark Insights. 2016;11:31–40. doi: 10.4137/BMI.S33191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Domingos MA, Queiroz M, Lotufo PA, Benseñor IJ, Titan SM. Serum RBP4 and CKD: Association with insulin resistance and lipids. J Diabetes Complications. 2017;31:1132–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2017.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Majerczyk M, Choręza P, Bożentowicz-Wikarek M, Brzozowska A, Arabzada H, Owczarek A, et al. Increased plasma RBP4 concentration in older hypertensives is related to the decreased kidney function and the number of antihypertensive drugs-results from the PolSenior substudy. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2017;11:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fakhruddin S, Alanazi W, Jackson KE. Diabetes-induced reactive oxygen species: Mechanism of their generation and role in renal injury. J Diabetes Res 2017. 2017:8379327. doi: 10.1155/2017/8379327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Q, Jiang CY, Chen BX, Zhao W, Meng D. The association between high-sensitivity C-reactive protein concentration and diabetic nephropathy: A meta-analysis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19:4558–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Varma V, Varma M, Varma A, Kumar R, Bharosay A, Vyas S, et al. Serum total sialic acid and highly sensitive C-reactive protein: Prognostic markers for the diabetic nephropathy. J Lab Physicians. 2016;8:25–9. doi: 10.4103/0974-2727.176230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Javanmardi M, Azadi NA, Amini S, Abdi M. Diagnostic value of cystatin C for diagnosis of early renal damages in type 2 diabetic mellitus patients: The first experience in Iran. J Res Med Sci. 2015;20:571–6. doi: 10.4103/1735-1995.165960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Rubeaan K, Youssef AM, Subhani SN, Ahmad NA, Al-Sharqawi AH, Al-Mutlaq HM, et al. Diabetic nephropathy and its risk factors in a society with a type 2 diabetes epidemic: A Saudi National Diabetes Registry-based study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e88956. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Svensson MK, Tyrberg M, Nyström L, Arnqvist HJ, Bolinder J, Östman J, et al. The risk for diabetic nephropathy is low in young adults in a 17-year follow-up from the Diabetes Incidence Study in Sweden (DISS).Older age and higher BMI at diabetes onset can be important risk factors. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2015;31:138–46. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]