Abstract

Background:

Significance of platelet distribution width (PDW) and mean platelet volume (MPV) in assessing disease activity of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) remains unclear. This study was aimed to evaluate PDW and MPV as potential disease activity markers in adult SLE patients.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 204 study participants, including 91 SLE patients and 113 age- and gender-matched healthy controls, were selected in this cross-sectional study. They were classified into three groups: control group (n = 113), active SLE group (n = 54), and inactive SLE group (n = 37). Demographic, clinical, and laboratory data were analyzed.

Results:

In patient group, PDW was statistically higher than that in control group (13.54 ± 2.67 vs. 12.65 ± 2.34, P = 0.012), and in active group, PDW was significantly increased compared to inactive group (14.31 ± 2.90 vs. 12.25 ± 1.55, P < 0.001). However, MPV was significantly lower in SLE group than in control group (10.74 ± 0.94 vs. 11.09 ± 1.14, P = 0.016). PDW was positively correlated with SLE disease activity index (P < 0.001, r = 0.529) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (P = 0.002, r = 0.321) and negatively correlated with C3 (P < 0.001, r = −0.419). However, there was no significant association between MPV and these study variables. A PDW level of 11.85% was determined as a predictive cutoff value of SLE diagnosis (sensitivity 76.9%, specificity 42.5%) and 13.65% as cutoff of active stage (sensitivity 52.6%, specificity 85.3%).

Conclusion:

This study first associates a higher PDW level with an increased SLE activity, suggesting PDW as a novel indicator to monitor the activity of SLE.

Keywords: Biomarkers, blood platelets, systemic lupus erythematosus

INTRODUCTION

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease which can affect several parts of the body even kidney and central nervous system.[1,2] SLE has become a serious threat to human health. It is characterized by emergence of anti-DNA antibodies and immune complex formation in many organ systems facilitated by increased apoptosis and impaired clearance and defective clearance of apoptotic cells.[3,4] However, the pathogenesis of SLE remains largely unknown. Traditionally, complement 3 (C3), complement 4 (C4), and C-reactive protein are thought probable biomarkers for SLE disease activity evaluation.[5] However, a sensitive and specific indicator which could quantify the susceptibility and activity of SLE is still lacking.[6]

Platelets (PLTs) have been demonstrated to play an important role in inflammatory reactions and immune responses. Platelet distribution width (PDW), which represents the heterogeneity in PLT morphology, is clinically related to PLT activation.[7] Another PLT function marker is mean platelet volume (MPV). MPV is the most commonly used measure of PLT size. These two PLT parameters are commonly evaluated during routine blood tests. They have been regarded as potential markers in PLT activation and have been studied in various inflammatory conditions such as prostatitis, hepatitis, respiratory and cardiovascular pathologies, and some dermatological diseases.[8,9,10,11,12,13,14] The MPV value was furthermore investigated as an indicator of disease activity.[15,16] However, according to our knowledge, there are no reports on both PDW and MPV in patients with SLE.

In the present study, we aimed to compare the PDW and MPV values between our cohort of SLE patients and the healthy controls, so as to determine the relationships between PDW and MPV values and SLE disease activity and further to assess whether these values could be used as indicators for the disease activity of SLE.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

In this cross-sectional study, a total of 91 SLE patients (12 males, 79 females) whose mean age was 35.75 ± 11.47 years (range, 14–69 years) and 113 healthy controls (10 males, 103 females) whose mean age was 36.35 ± 11.66 years (range, 19–69 years) used as controls were registered from December 2014 to August 2016. Age and gender distributions were similar in patient and control groups. All patients met the 1997 updates of the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of SLE.[17] All the study participants provided informed consents. This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Huashan Hospital and was conducted in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki. The disease activity assessment was performed in accordance with the SLE disease activity index (SLEDAI-2000).[18] The data were collected before treatment. These patients were further divided into the active group (SLEDAI ≥6) and inactive group (SLEDAI <6). Individuals with infection, thrombocytopenia, uncontrolled hypertension, and other connective tissue diseases were excluded from this study. A history of smoking, hemoglobin >16.5 g/dl, anemia, angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, diabetes mellitus, antiphospholipid syndromes, recurrent miscarriage, amyloidosis, thrombosis or chronic renal insufficiency, pregnant, alcohol addiction, heart, renal or hepatic failure, chronic obstructive lung disease, metabolic syndrome, malignancy, and thyroid function disorder that might influence PLT indices were also excluded.

Sample collection

The whole blood and the serum samples were extracted from each study individual before treatment. White blood cell (WBC) count, absolute neutrophil (NEU) count, absolute lymphocyte (LYM) count, PLT count, PDW, and MPV were determined using an automated hematology analyzer (XN-9000; Sysmex Co., Kobe, Japan). Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and complement 3 (C3) were evaluated by automatic analyzers (TSET1; Alifax Co., Polverara, Italy and BN II; Siemens Co., Marburg, Germany, respectively). The following data were collected: Sex, age, WBC, NEU, LYM, PLT, PDW, MPV, ESR, C3, cutaneous manifestations, and SLEDAI score.

Statistical analysis

The SPSS statistical software for windows version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used. All data were expressed as means ± standard deviations. An independent sample t-test was used to compare normally distributed continuous variables between the two groups and a Mann–Whitney U-test when the distribution was skewed. Pearson or Spearman correlation analysis was used to assess the relationship between PLT parameters and the other study variables, as appropriate. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was constructed to estimate the sensitivity value as a biomarker of SLE. The sensitivity, specificity, area under curve (AUC), and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated. G*Power 3.1 (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang and Buchner, 2007, Germany) software was used to calculate power of test.[19,20] A two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Changes in lymphocyte, platelet distribution width, and mean platelet volume in systemic lupus erythematosus patients

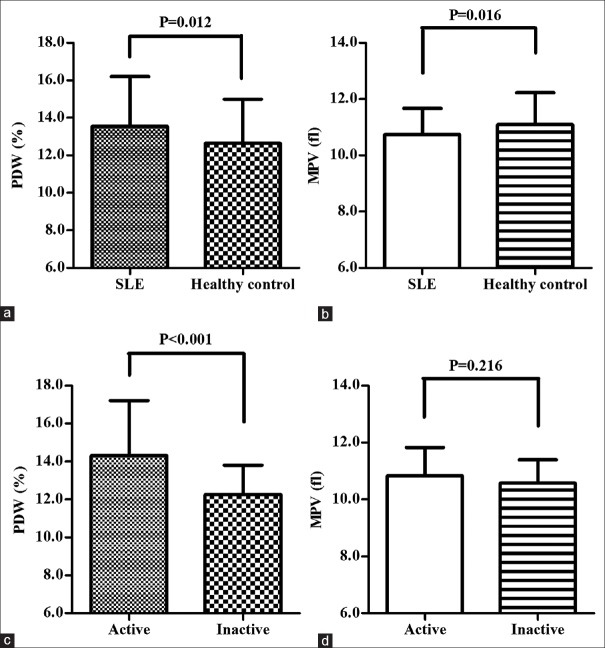

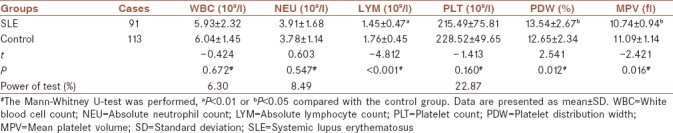

The clinical data detected in the SLE patient group and control group are summarized in [Table 1]. The PDW values were significantly increased (13.54 ± 2.67 vs. 12.65 ± 2.34, P = 0.012) whereas the LYM and MPV levels were statistically decreased in patients compared to controls (1.45 ± 0.47 vs. 1.76 ± 0.45, P < 0.001; 10.74 ± 0.94 vs. 11.09 ± 1.14, P = 0.016). The PDW and MPV values in the patient and control groups are displayed in Figure 1a and b, respectively. Whereas, there was no significant difference in the WBC, NEU, as well as PLT values between these two groups (P = 0.672, 0.547, and 0.160, respectively).

Table 1.

Parameters of systemic lupus erythematosus patients and healthy controls

Figure 1.

PDW and MPV of SLE patients with varying disease activities and controls. (a) The PDW values of SLE patients (n = 91) were significantly higher than those of controls (n = 113; P = 0.012). (b) The MPV values of SLE patients (n = 91) were significantly lower than those of controls (n = 113; P = 0.016). (c) A significant difference in PDW was observed between patients with active and those with inactive SLE (P < 0.001). (d) No significant difference in MPV was observed between patients with active and those with inactive SLE. PDW = Platelet distribution width; MPV = Mean platelet volume; SLE = Systemic lupus erythematosus

Differences of platelet distribution width, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index, white blood cell, neutrophil, lymphocyte, platelet, and C3 between patients with active and inactive systemic lupus erythematosus

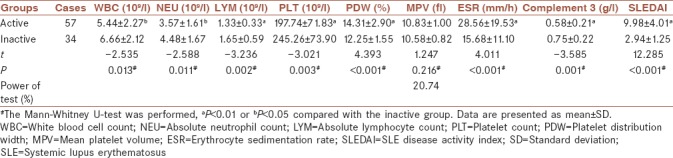

Table 2 demonstrates the laboratory data of the active and inactive study groups. Figure 1c shows that PDW in the active SLE group was significantly higher than that in the inactive SLE group (14.31 ± 2.90 vs. 12.25 ± 1.55, P < 0.001) although as shown in Figure 1d, MPV was not significantly different between the two groups (P = 0.216).

Table 2.

Parameters of active and inactive groups

Besides, ESR and SLEDAI scores were significantly increased in patients in active group than in inactive group (28.56 ± 19.53 vs. 15.68 ± 11.10, P < 0.001; 9.98 ± 4.01 vs. 2.94 ± 1.25, P < 0.001). The WBC, NEU, LYM, PLT, and C3 levels were statistically decreased in active group than in inactive group (5.44 ± 2.27 vs. 6.66 ± 2.12, P = 0.013; 3.57 ± 1.61 vs. 4.48 ± 1.67, P = 0.011; 1.33 ± 0.33 vs. 1.65 ± 0.59, P = 0.002; 197.74 ± 71.83 vs. 245.26 ± 73.90, P = 0.003; and 0.58 ± 0.21 vs. 0.75 ± 0.22, P = 0.001, respectively).

Correlation of disease activity with platelet distribution width

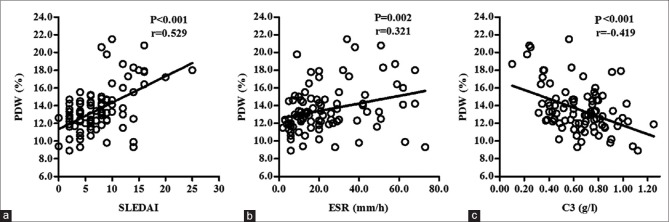

The correlations between PDW and the other study variables are shown in Figure 2. PDW was positively correlated with SLEDAI (P < 0.001, r = 0.529) and ESR (P = 0.002, r = 0.321) and negatively correlated with C3 (P < 0.001, r = −0.419). However, there was no significant association between MPV and SLEDAI, ESR, as well as C3 (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Relative analysis of SLEDAI, ESR, and C3 with PDW. The number of SLE patients was 91. Each point represents one pair of data (x and y value). There were significant positive and linear associations of (a) SLEDAI (P < 0.001, r = 0.529) and (b) ESR (P = 0.002, r = 0.321) with PDW. (c) Significant negative and linear association of C3 titters with PDW was observed (P < 0.001, r = −0.419). SLEDAI = Systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index; ESR = Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; C3 = Complement 3; PDW = Platelet distribution width; SLE = Systemic lupus erythematosus

Association between clinical manifestations and platelet distribution width as well as mean platelet volume

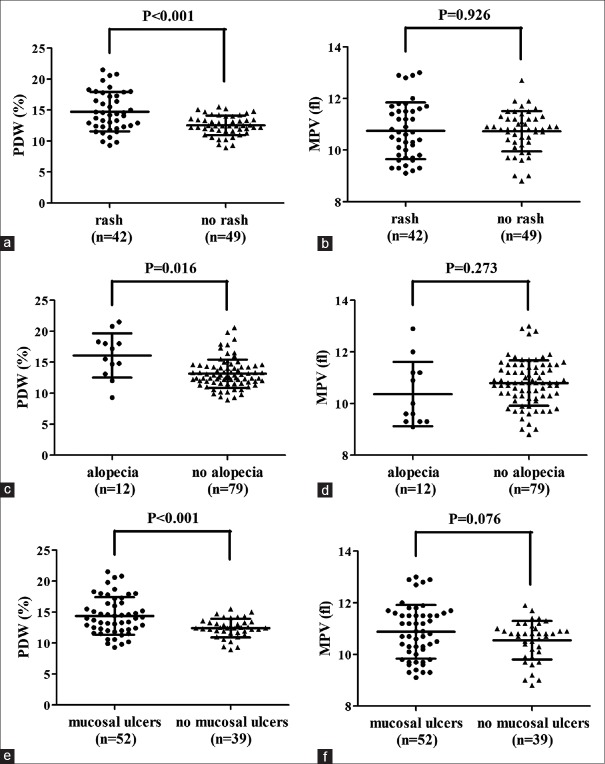

Analysis of associations between cutaneous manifestations (including rash, alopecia, and mucosal ulcers) and PDW and MPV was conducted. There was significant difference of PDW values between rash and no rash (14.72 ± 3.18 vs. 12.53 ± 1.56, P < 0.001) [Figure 3a], alopecia and no alopecia (16.10 ± 3.57 vs. 13.15 ± 2.29, P = 0.016) [Figure 3c], and mucosal ulcers and no mucosal ulcers patients (14.38 ± 3.03 vs. 12.42 ± 1.50, P < 0.001) [Figure 3e]. However, no evident difference of MPV values between rash and no rash (10.75 ± 1.10 vs. 10.73 ± 0.78, P = 0.926) [Figure 3b], alopecia and no alopecia (10.37 ± 1.25 vs. 10.79 ± 0.88, P = 0.273) [Figure 3d], and mucosal ulcer and no mucosal ulcer (10.88 ± 1.04 vs. 10.55 ± 0.75, P = 0.076) [Figure 3f] patients was obtained.

Figure 3.

PDW and MPV of different clinical cutaneous manifestations. Significant difference of PDW values between (a) rash and no rash (14.72 ± 3.18 vs. 12.53 ± 1.56, P < 0.001), (c) alopecia and no alopecia (16.10 ± 3.57 vs. 13.15 ± 2.29, P = 0.016), (e) mucosal ulcer and no mucosal ulcer patients (14.38 ± 3.03 vs. 12.42 ± 1.50, P < 0.001) was shown. But no evident difference of MPV values between (b) rash and no rash (10.75 ± 1.10 vs. 10.73 ± 0.78, P = 0.926), (d) alopecia and no alopecia (10.37 ± 1.25 vs. 10.79 ± 0.88, P = 0.273), (f) mucosal ulcers and no mucosal ulcers (10.88 ± 1.04 vs. 10.55 ± 0.75, P = 0.076) was obtained. PDW = Platelet distribution width; MPV = Mean platelet volume

The area under curve of platelet distribution width

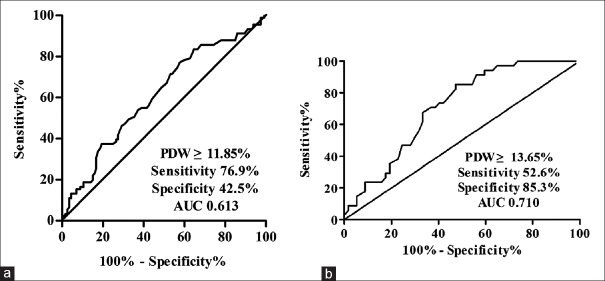

An ROC/AUC was drawn by plotting the sensitivity versus the specificity for different cutoff levels of PDW and MPV for predicting diagnosis and activation of SLE. We prepared ROC curve with a cutoff point of PDW level (11.85%) to ensure the diagnostic threshold that the AUC achieved maximal value of 0.613 (95% CI 0.535–0.690). Based on the judgment, PDW made a considerable sensitivity 76.9% and specificity 42.5% (P = 0.006) [Figure 4a]. It was further revealed that cutoff PDW value for predicting activation of SLE was 13.65% (AUC = 0.710; 95% CI, 0.606–0.814) with a sensitivity of 52.6% and a specificity of 85.3% (P = 0.001) [Figure 4b]. However, the AUC of MPV indicated no significance (data not shown).

Figure 4.

ROC analysis for PDW. (a) The ROC/AUC analysis of PDW values as diagnosis markers of SLE demonstrated a sensitivity of 76.9% and a specificity of 42.5% (AUC = 0.613; 95% CI, 0.535–0.690) when a cutoff value of 11.85% was used for PDW (P = 0.006). (b) It was also revealed that PDW for predicting activation of SLE was 13.65% (AUC = 0.710; 95% CI, 0.606–0.814) with a sensitivity of 52.6% and a specificity of 85.3% (P = 0.001). ROC = Receiver-operating characteristics curve; PDW = Platelet distribution width; AUC = Area under curve; SLE = Systemic lupus erythematosus; CI = Confidence interval

DISCUSSION

SLE is a chronic autoimmune disease that often follows relapsing-remitting courses. PLT activation, whose pathophysiology involves inflammatory cytokines and complements, has been observed in patients with SLE.[21,22] Moreover, such activation of PLTs can compensate for the decrease in the PLT count consumed in SLE. This may provide probable biomarkers to respond the changes in disease activity.

PLTs are discoid cells with a length of 1–2 μm and an average lifespan of 8–10 days.[23] PDW, which reflects the range of variability in the PLT size, and MPV, which is the average of PLT volume, are widely used for assessing PLT function and activation. These two PLT parameters have become popular and vital markers of PLT activation. As for skin disorders, Kim's study showed that the PDW and MPV values were higher in patients with psoriasis, which is a chronic inflammatory skin disease similar to SLE than healthy controls. According to Kim's study, the MPV levels were reported to show a positive correlation with psoriasis disease activity.[13] Another study of Ozlu et al. revealed that the PDW levels were higher and the MPV values were lower in the Lichen Planus group when compared to a control group, which is consistent with the present study.[14] Association between MPV and other connective tissue diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is still controversial. Some researchers demonstrated that MPV might not be able to predict disease activity in RA patients while others showed that MPV was significantly higher with high disease activity compared to RA patients with low-to-moderate disease activity.[24,25] The discrepancies might be clarified by confounding factors yet to be discovered and additional challenge relating to methodological issues. What's more, it was investigated by Safak et al. that the MPV values of SLE patients during the active arthritis period were significantly lower than those of SLE patients during remission and healthy controls.[26] One plausible mechanism to explain the decreased MPV values could be the consumption of large activated PLTs in extravascular sites of inflammation.[15] On the contrary, MPV in juvenile SLE patients was statistically higher than in controls and significantly increased during active phase compared to during inactive phase.[27] This could be partly explained by the work of Kutti and Bergström that SLE patients have normal values for PLT mean life span while PLT activation is enhanced in them, suggesting that PLT consumption is minimal.[28]

The current study manifested higher PDW values and lower MPV values in SLE patients than healthy controls and the positive relationship between PDW and disease activity. This was compatible with the significant difference of PDW on cutaneous damages in our report. More studies are needed to further elucidate the cause of this relationship. A cutoff value presents the truncation point of a certain value to determine the threshold. Accordingly, the present study indicated that the best truncation value of PDW to diagnose SLE was 11.85%, with a sensitivity of 76.9% and a specificity of 42.5%. It was further studied that PDW 13.65% with a sensitivity of 52.6% and a specificity of 85.3% was more suitable as the truncation point on determining active or inactive stage of SLE patients. These results suggest that those individuals with PDW values ≥11.85% have an increased risk of SLE onset and those SLE patients with PDW values ≥13.65% are more likely in active stage. Therefore, PDW could serve as a valid and reliable marker for clinical assessment of SLE and reduce medical costs.

In addition, SLEDAI score, ESR, and serum C3 are frequently used traditional indicators in the diagnosis and assessment of SLE.[5,29] Our data revealed that the elevated SLEDAI score and ESR and the reduced serum C3 levels in the active SLE group were in accordance with classical literature data, therefore supporting the usefulness of these classical biomarkers for monitoring SLE patients.

As indicated with poor power of test, the present study was limited by the single-center nature of the study design. In addition, the relative small sample size might affect its external validation. A series of further controlled prospective longitudinal observations in larger SLE populations and molecular biological studies could provide more evidence to confirm the prognostic and diagnostic utility of PDW and MPV in the clinical practice.

CONCLUSIONS

The present study reports on the association of a higher PDW level with an enhanced SLE activity for the first time, indicating the PDW value as an alternative and complimentary marker to monitor SLE.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81373212, 81371745 and 81402605).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank the reviewers for their helpful comments and the editors for their kind work on this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Saadatnia M, Sayed-Bonakdar Z, Mohammad-Sharifi G, Sarrami AH. Prevalence and prognosis of cerebrovascular accidents and its subtypes among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus in Isfahan, Iran: A Hospital clinic-based study. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5:123–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feng M, Lv J, Fu S, Liu B, Tang Y, Wan X, et al. Clinical features and mortality in Chinese with lupus nephritis and neuropsychiatric lupus: A 124-patient study. J Res Med Sci. 2014;19:414–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hajizadeh N, Laijani FJ, Moghtaderi M, Ataei N, Assadi F. A treatment algorithm for children with lupus nephritis to prevent developing renal failure. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5:250–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy DM, Kamphuis S. Systemic lupus erythematosus in children and adolescents. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2012;59:345–64. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li W, Li H, Song W, Hu Y, Liu Y, DA R, et al. Differential diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis with complements C3 and C4 and C-reactive protein. Exp Ther Med. 2013;6:1271–6. doi: 10.3892/etm.2013.1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu CC, Ahearn JM. The search for lupus biomarkers. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2009;23:507–23. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osselaer JC, Jamart J, Scheiff JM. Platelet distribution width for differential diagnosis of thrombocytosis. Clin Chem. 1997;43:1072–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aktas G, Cakiroglu B, Sit M, Uyeturk U, Alcelik A, Savli H, et al. Mean platelet volume: A simple indicator of chronic prostatitis. Acta Med Mediterr. 2013;29:515–54. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pan Y, Muheremu A, Wu X, Liu J. Relationship between platelet parameters and hepatic pathology in patients with chronic hepatitis B infection – A retrospective cohort study of 677 patients. J Int Med Res. 2016;44:779–86. doi: 10.1177/0300060516650076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu Y, Lou Y, Chen Y, Mao W. Evaluation of mean platelet volume in patients with hepatitis B virus infection. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:4207–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akyol S, Çörtük M, Baykan AO, Kiraz K, Börekçi A, Şeker T, et al. Mean platelet volume is associated with disease severity in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2015;70:481–5. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2015(07)04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Surgit O, Pusuroglu H, Erturk M, Akgul O, Buturak A, Akkaya E, et al. Assessment of mean platelet volume in patients with resistant hypertension, controlled hypertension and normotensives. Eurasian J Med. 2015;47:79–84. doi: 10.5152/eurasianjmed.2015.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim DS, Lee J, Kim SH, Kim SM, Lee MG. Mean platelet volume is elevated in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Yonsei Med J. 2015;56:712–8. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2015.56.3.712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozlu E, Karadag AS, Toprak AE, Uzuncakmak TK, Gerin F, Aksu F, et al. Evaluation of cardiovascular risk factors, haematological and biochemical parameters, and serum endocan levels in patients with lichen planus. Dermatology. 2016;232:438–43. doi: 10.1159/000447587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gasparyan AY, Ayvazyan L, Mikhailidis DP, Kitas GD. Mean platelet volume: A link between thrombosis and inflammation? Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:47–58. doi: 10.2174/138161211795049804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kisacik B, Tufan A, Kalyoncu U, Karadag O, Akdogan A, Ozturk MA, et al. Mean platelet volume (MPV) as an inflammatory marker in ankylosing spondylitis and rheumatoid arthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2008;75:291–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hochberg MC. Updating the American college of rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gladman DD, Ibañez D, Urowitz MB. Systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index 2000. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:288–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175–91. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41:1149–60. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boilard E, Blanco P, Nigrovic PA. Platelets: Active players in the pathogenesis of arthritis and SLE. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8:534–42. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Habets KL, Huizinga TW, Toes RE. Platelets and autoimmunity. Eur J Clin Invest. 2013;43:746–57. doi: 10.1111/eci.12101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ataseven A, Ugur Bilgin A. Effects of isotretinoin on the platelet counts and the mean platelet volume in patients with acne vulgaris. Scientific World Journal 2014. 2014:156464. doi: 10.1155/2014/156464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moghimi J, Ghahremanfard F, Salari M, Ghorbani R. Association between mean platelet volume and severity of rheumatoid arthritis. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;27:276. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2017.27.276.12228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Talukdar M, Barui G, Adhikari A, Karmakar R, Ghosh UC, Das TK, et al. A study on association between common haematological parameters and disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:EC01–EC04. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/23524.9130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Safak S, Uslu AU, Serdal K, Turker T, Soner S, Lutfi A, et al. Association between mean platelet volume levels and inflammation in SLE patients presented with arthritis. Afr Health Sci. 2014;14:919–24. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v14i4.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yavuz S, Ece A. Mean platelet volume as an indicator of disease activity in juvenile SLE. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33:637–41. doi: 10.1007/s10067-014-2540-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kutti J, Bergström AL. Platelet kinetics in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), with special reference to corticosteroid and azathioprine therapy. Scand J Rheumatol. 1981;10:266–8. doi: 10.3109/03009748109095312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stojan G, Fang H, Magder L, Petri M. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate is a predictor of renal and overall SLE disease activity. Lupus. 2013;22:827–34. doi: 10.1177/0961203313492578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]