Abstract

The objective of the study was to conduct a concept analysis of “self-management of cancer pain” to develop a theoretical definition of the concept and identify its attributes, antecedents, and outcomes. The Rodgers' evolutionary model of concept analysis was used. Literature published from January 2000 to February 2017 containing the terms, “cancer pain” and “self-management” in their title and/or abstract was assessed. Twenty-seven studies were selected for this analysis. Self-management of cancer pain is defined as “the process in which patients with cancer pain make the decision to manage their pain, enhance their self-efficacy by solving problems caused by pain, and incorporate pain-relieving strategies into daily life, through interactions with health-care professionals.” The attributes of self-management of cancer pain were classified into the following five categories: Interaction with health-care professionals, decision-making to pain management, process for solving pain-related problems, self-efficacy, and incorporating strategies for pain relief into daily life. The antecedents were classified into the following seven categories: Physical functions, cognitive abilities, motivation, undergoing treatment for pain, receiving individual education, receiving family and health-care professionals' support, and health literacy. The outcomes were classified into the following three categories: pain relief, well-being, and empowerment. The attributes of self-management of cancer pain can be used as components of nursing practice to promote patient self-management of cancer pain. The categories of antecedents can be used as indicators for nursing assessment, and the outcomes can be used as indicators for evaluations of nursing intervention.

Keywords: Cancer pain, concept analysis, self-management

Introduction

Cancer pain is a symptom experienced by most cancer patients. It is reported that 60% of outpatients with advanced cancer experience pain, with 20% of them having moderate or severe pain and about half of them experiencing physical and mental suffering.[1] In Japan, cancer treatment, except operative therapy, is provided on an outpatient basis, and the average length of hospital stay has been shortened to 19.9 days.[2] Under this circumstance, cancer patients are required to voluntarily self-manage cancer pain and problems caused by the pain. The concept of self-management has been mainly used for patients with chronic disease. In the area of cancer nursing, the Oncology Nursing Society added “self-management” as one of the priority topics for research in the survey they conducted in 2013.[3] The mainstream view of health-care professionals had been that patients with cancer pain should join the pain management provided by health-care professionals. However, it has been shifting to the view that patients may voluntarily self-manage their cancer pain.

The use of the concept of self-management started in a study aiming to verify the effectiveness of a training to quit smoking in 1971.[4] Since then, the concept has been used in educational programs for patients with arthritis pain,[5] behavioral and psychological approaches to the assessment and treatment of chronic pain,[6] and self-management by patients with fatigue from chemotherapy.[7] Among the studies that used the concept of self-management of cancer pain, one was a qualitative study targeting patients with metastatic bone pain,[8] intervention studies aiming to promote self-management by patients with cancer pain,[9,10,11] and a qualitative study that shed light on self-management of pain by patients with advanced cancer from the viewpoint of palliative professionals.[12] Based on these studies, the concept of self-management by patients with cancer pain could be considered a new concept; however, the distinction from the similar concepts such as pain management or self-care is unclear. While a study on concept analysis of “older adults' persistent pain self-management”[13] has been published at present, it is necessary to find out the characteristics of the concept of self-management of cancer pain to consider concrete strategies for nursing care for patients with cancer pain. In this study, a concept analysis was conducted on “self-management of cancer pain” aiming to develop a theoretical definition of the concept, identify its attributes, antecedents, and outcomes.

Methods

A model of concept analysis

In this study, Rodgers' evolutionary model of concept analysis was used.[14] Rodgers' evolutionary method of concept analysis is intended to identify the characteristics of a concept by comparing it with its relevant concepts. In Rodgers' model, the characteristics of concept are shown in attributes, antecedents, and outcomes. Rodgers' model is suited for determining what kind of consensus has been achieved for the concept of “self-management of cancer pain” and how it is used in medical and nursing science. Rodgers' model uses the term “consequence” instead of “outcome.” However, since self-management is considered to be a subjective and affirmative action of patients with cancer pain, this study used “outcome.”

Studies included in the analysis

PubMed, CINAHL, and the search system of ICHUSHI were used for the literature search. The target years of literature search were from January 2000 to February 2017. The target languages were English and Japanese. The terms used for the literature search were “cancer pain,” “self-management,” “self-control,” and “self-care.” Studies containing these terms in their titles and/or abstracts were selected. As a result, 232 studies (218 English studies and 14 Japanese studies) were selected. From the 232 studies, 27 were omitted because of double selection; hence 205 studies remained. Of the 205 studies (191 English studies and 14 Japanese studies), 18 studies dealt with noncancer patients – such as elderly patients with arthralgia – 3 studies dealt with child patients and 3 studies did not adopt the format for research papers. Therefore, these 24 studies were omitted from the 205 studies and 181 studies remained (176 English studies and 5 Japanese studies). Among the 181 studies, 160 studies that did not contain “self-management” in their titles and/or abstracts were omitted and 21 studies remained (18 English studies and 3 Japanese studies). PubMed MeSH classifies “self-management” and “self-care” into the same entry category. Since this study aims to analyze the concept of self-management of cancer pain, it attaches importance to the term “self-management.” In addition, since studies on self-management of cancer pain must be collected from various fields, information retrieval systems, such as Google Search, were used for the literature search. Consequently, 6 studies were added to the 21 studies. Finally, 27 studies (23 English studies and 4 Japanese studies)[3,8,9,10,11,12,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35] were used for the concept analysis of self-management of cancer pain.

Data collection and analysis

The target studies were read in detail and the basic information (author's name, publication year, title, and study design) was extracted as well as the definitions, attributes, antecedents, outcomes, and concepts, all of which are related to the concept of self-management of cancer pain. These were entered into the created matrix sheet. The descriptive data of attributes, antecedents, and outcomes were classified into codes according to their meanings. The codes were then sorted into subcategories based on similarity, and the subcategories were sorted into further categories in the same way. A definition of “self-management of cancer pain” was created after considering the relevance among these categories. Students in a doctoral course in nursing science provided their input to ensure the validity of this concept analysis. In addition, the study was supervised by an instructor for the doctoral course of nursing science during the whole process of this concept analysis.

Results

Related concepts

In the target literature of this study, the following concepts were used in relation to self-management of cancer pain. With respect to the relationship between the terms “self-care” and “self-management,” “self-management” was used as an element of “self-care” in some studies,[10,12,21] while “self-care” and “self-management” were considered to have the same meaning in another study.[10] None of the studies made a clear distinction between the terms “self-management” and “self-care” in their use. The term “Pain management” was described as patients efforts to relieve pain[10,22,24] and as practiced by a health-care professional such as a nurse.[27,31] The term “Self-medication” was used only to mean self-management of an analgesic.[8,18] The term “Self-action” was described as an action originated by oneself to maintain pain control in daily life.[12,15] The term “Self-regulation” was used to mean patients taking a smaller dose of an analgesic than was prescribed.[12]

Constructs of self-management of cancer pain

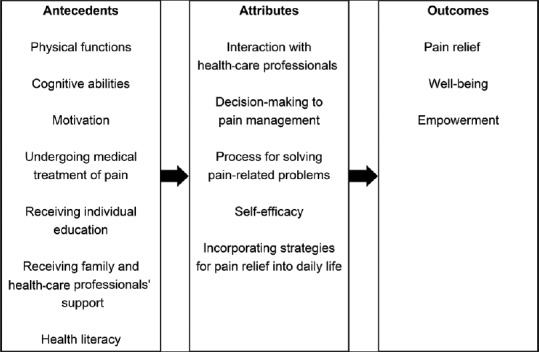

The attributes, antecedents, and outcomes extracted as constructs of self-management of cancer pain are shown in Figure 1, which presents the results according to Rodgers' phases of evolutionary concept analysis.

Figure 1.

Self-management of cancer pain: antecedent, attribute and outcome

Theoretical definition

Based on the attributes, antecedents, and outcomes that were found in this study, self-management of cancer pain can be defined as follows: The process in which patients with cancer pain make the decision to manage their pain, enhance their self-efficacy by solving problems caused by the pain, and incorporate pain-relieving strategies into daily life, through interactions with health-care professionals.

Attributes

The attributes of self-management of cancer pain were classified into the following five categories as shown in Table 1: Interaction with health-care professionals, Decision-making to pain management, Process for solving pain-related problems, Self-efficacy, Incorporating strategies for pain relief into daily life.

Table 1.

Self-management of cancer pain<attributes>

| Category | Subcategory | Code | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interaction with health-care professionals | Communication with health-care professionals | Contacting support when needed | 10,11,19,22,27,28 |

| Questions and consultation with health-care professionals | 11,12,28,35 | ||

| Communication with health-care professionals | 10,11,21,22,25 | ||

| Negotiation about preferable pain management for patient with healthcare professionals | 12,35 | ||

| Partnership with healthcare professionals | Discussion with health-care professionals | 8,24 | |

| Sharing the pain situation with health-care professionals | 8,19,21,28 | ||

| Collaboration with health-care professionals | 3,15,26,27,28 | ||

| Partnership with health-care professionals | 22,28,30 | ||

| Decision-making to pain management | Active participation in pain management | Active attitude for pain management | 10,21 |

| Self-activation for pain management | 15 | ||

| Active participation in pain management | 28,29 | ||

| Responsibility for pain management | Morality and responsibility for using opioid analgesic | 18 | |

| Consistently taking initiative for their own health care | 22 | ||

| Determination to self-manage pain | The intention to manage opioid analgesics | 32,33,34 | |

| Willingness to accept a new pain management method | 12,18,24 | ||

| Accepting ownership of pain control | 12,19,27,28 | ||

| Autonomous action | 12 | ||

| Process for solving pain-related problems | Process | Changing process | 11,12,27 |

| Complicated process | 9,19 | ||

| Developmental process | 27 | ||

| Understanding pain conditions | Understanding pain conditions | 10,12,19,28,35 | |

| Understanding one’s own pain | 20,35 | ||

| Having standards of pain control | 12,30 | ||

| Goal setting for pain relief | Goal setting for pain relief | 8,17,25,26,27,28,30 | |

| Planning for pain relief | Tailored pain relief plan | 8,22,27 | |

| A realistic pain relief plan | 30,35 | ||

| Consideration of use and method for analgesic drugs | 35 | ||

| Implementing pharmacological pain relief strategies | Adherence to medication | 10,11,12,18,21,28 | |

| Supervision and use of rescue dose | 32,33,34,35 | ||

| Monitoring side effects of analgesic drugs | 10,28,35 | ||

| Implementing nonpharmacological pain relief strategies | Use of the nonpharmacological pain relief strategies | 10,11,12,15,21 | |

| Positioning | 8,35 | ||

| Integration of emotions | 8,12,17,28,35 | ||

| Self-monitoring | Self-monitoring of pain | 11,20,25 | |

| Self-monitoring of the effects of an analgesic drug and its side effects | 11,19,24 | ||

| Use of a pain diary | 24,26 | ||

| Evaluation of pain-relieving effect | Evaluate change in pain. | 35 | |

| Evaluate the effects of medical treatment | 8,26,35 | ||

| Modification of pain-relieving plan | Modification of pain-relieving plan with the data from self-monitoring | 11,26 | |

| Self-efficacy | Self-efficacy | Self-efficacy | 7,8,17,19 |

| Confidence | Confidence | 27 | |

| Confidence in problem-solving | 30 | ||

| Confidence in pain management | 28,35 | ||

| Confidence and motivation for the next step | 35 | ||

| Incorporating strategies for pain relief into daily life | Incorporating strategies for pain relief into daily life | Every day | 18 |

| Incorporating strategies of pain relief into daily life | 9 | ||

| Using problem-solving skills for pain as a part of daily life | Using problem-solving skills for pain as a part of daily life | 25 | |

| Maintaining pain control into daily life | Maintaining desirable pain control into daily life | 12 |

Interaction with health-care professionals

This category of attributes includes two subcategories, namely, “Communication with health-care professionals” and “Partnership with health-care professionals.” The methods to interact with health-care professionals included “Negotiation with health-care professionals about preferable pain management for patient”[12,35] and “Discussion with health-care professionals.”[8,24]

Decision-making to pain management

This category of attributes includes three subcategories, namely, “Active participation in pain management,” “Responsibility for pain management,” and “Determination to self-manage pain.” “Responsibility for pain management” was described as “Morality and responsibility for using opioid analgesics”[18] and “Consistently taking initiative for their own health care.”[22]

Process for solving pain-related problems

This category of attributes includes nine subcategories, namely, “Process,” “Understanding pain conditions,” “Goal setting for pain relief,” “Planning for pain relief,” “Implementing pharmacological pain relief strategies,” “Implementing nonpharmacological pain relief strategies,” “Self-monitoring,” “Evaluation of pain-relieving effect,” and “Modification of pain-relieving plan.” “Process” was described as a complicated process,[9,19] changing process,[11,12,27] and development process.[27] Process for solving pain-related problems involves understanding one's own pain[20,35] and having standards of pain control,[12,30] by which patients try to “Understand pain condition,” and make a realistic[30,35] and tailored pain-relieving plan for themselves,[8,22,27] by “Goal setting for pain relief.” Patients “Implement pharmacological” and/or “nonpharmacological pain relief strategies” based on this plan and implement “Self-monitoring” using a pain diary[24,26] and such. As a result, they make an “Evaluation of pain-relieving effect” by evaluating the change in pain[35] and the effects of medical treatment.[8,26,35] If the pain is not relieved, they make a “Modification of pain-relieving plan.” This is a set of processes for solving pain-related issues.

Self-efficacy

This category of attributes includes two subcategories, namely, “Self-efficacy” and “Confidence.” Patients' “Confidence” was described as confidence in problem-solving,[30] confidence in pain management,[28,35] and confidence and motivation for the next step.[35]

Incorporating strategies for pain relief into daily life

This category of attributes includes three subcategories, namely, “Incorporating strategies for pain relief into daily life,” “Using problem-solving skills for pain as a part of daily life,” and “Maintaining pain control in daily life.”

Antecedents and outcomes

The antecedents of self-management of cancer pain were classified into the following seven categories as shown in Table 2: Physical functions, Cognitive abilities, Motivation, Undergoing medical treatment for pain, Receiving individual education, Receiving family and health-care professionals' support, and Health literacy. The contents of Receiving individual education were teaching knowledge and skills required for medication,[9,11,12,19,21,24,25,26,29,33] clearing up a misconception about pain treatment,[10,21,27,29] and instructing how to use a self-report.[9,10,20,21,22,27,34] The contents of “Coaching” were coaching on problem-solving skills[9,12,25,26,27,29] and coaching how to communicate with the attending physician.[9,10,21,25,26,27,29]

Table 2.

Self-management of cancer pain<antecedents>

| Category | Subcategory | Code | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical functions | Good physical functions | A comparatively good functional state | 24,34 |

| Independence | 18 | ||

| Cognitive abilities | Capability to understand information | Capability to understand information | 18,20 |

| Capability for new learning | 24 | ||

| Capability required for self-management | 12,20 | ||

| Medicinal self-control capability | Judgment by healthcare professional that medicinal self-control is possible | 32,33 | |

| Self-control for nonopioid analgesics | 34 | ||

| Concentration | The capability to concentrate on life | 3 | |

| Motivation | Belief in pain relief | Belief in not putting up with pain | 35 |

| Belief in not giving up | 35 | ||

| Expectations for pain relief | Expectation for pain relief | 24 | |

| Wanting new ways to manage pain | 8 | ||

| Self-motivation for pain management | Motivation for performing pain management | 12,19,27 | |

| Motivation leading to self-action | 12,16 | ||

| Undergoing medical treatment for pain | Diagnosis of pain | Diagnosis of pain | 25 |

| Prescription of an analgesic drug | Prescription of analgesic drugs | 8,11,19 | |

| Cultural situations and analgesic drug use | 18 | ||

| Receiving individual education | Individual intervention | Individual intervention | 12,16,24,25,28,30 |

| Education of knowledge and skills required for pain management | Education about knowledge and skills required for medication | 9,11,12,19,21,24,25,26,29,33 | |

| Education on misconceptions about pain treatment | 10,21,27,29 | ||

| Education on using a self-report | 9,10,20,21,22,27,34 | ||

| Coaching | Coaching about problem-solving skills | 9,12,25,26,27,29 | |

| Coaching about communication with the attending physicians | 9,10,21,25,26,27,29 | ||

| Receiving family and healthcare professionals’ support | Support from family | Family understanding about pain management | 8,24 |

| Participation of the family in pain management | 12,18,21,25,28 | ||

| Support from healthcare professionals | Healthcare professional’s sincerity | 18,27,35 | |

| Support from healthcare professionals | 8,21,28 | ||

| Health literacy | Access to information | Access to information for obtaining suitable support | 12,15,19,26 |

| Use of resources | Use of human and social resources | 3,35 | |

| Health literacy | Health literacy | 20 |

The outcomes of self-management of cancer pain were classified into three categories as follows: Pain relief, Well-being and Empowerment as shown in Table 3. “Optimization of medication” in the category of Pain relief was described as an improvement in patient adherence to medication[3,10,22,27,34] and dose adjustment of analgesics by patient to optimum dose.[9,23,28,32,34,35]

Table 3.

Self-management of cancer pain<outcomes>

| Category | Subcategory | Code | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain relief | Improvement in pain management | Improvement in the knowledge about pain management | 9,10,20,22 |

| Improved pain control | 19 | ||

| Optimization of medication | Improvement in patient adherence to medication | 3,10,22,27,34 | |

| Dose adjustment of analgesic by patient to optimum dose | 9,23,28,32,34,35 | ||

| Pain relief | Decrease in pain intensity | 10,12,15,16,17,19,20,22,23,24,28,32 | |

| Pain control | 8,9,10,11,17,27,28,34 | ||

| Well-being | Improvement of QOL | Improvement of QOL | 10,11,12,18,19,30 |

| Improvement of effects related to pain | Improvement of effects related to pain | 10,15,20 | |

| Positive emotions | Positive emotions | 17,22 | |

| Sense of security | Sense of security from familiarity of a pain management strategy | 24 | |

| Sense of security from having analgesic drug at hand | 32,33 | ||

| Satisfaction | High satisfaction | 24 | |

| Sufficiency of self-management | 28 | ||

| Empowerment | Empowerment | Empowerment | 3,10,15,27,28,29,31 |

| Restoration of self-reliance | Restoration of self-confidence | 30 |

Discussion

The term “self-management of cancer pain” has been considered to be included in, or have the same meaning as, the terms “pain management” and “self-care.” However, the results of this study show that self-management of cancer pain is a process in which patients solve cancer-related problems by themselves through interaction with healthcare professionals.

Seven categories for extracted antecedents of self-management of cancer pain were considered as indicators to assess whether a patient with cancer pain can implement self-management. The patients' relatively good physical and intact cognitive functions (i.e. able to understand information and administer medication to themselves) are prerequisites for their self-management of cancer pain. For this reason, nurses have to assess patients' physical functions, independence in daily life, state of cognitive functions, situation of self-management of medication, concentration, level of expectation toward pain relief, and willingness to act by themselves, and get information about available human and social resources. The category of Receiving individual education indicates that self-management of cancer pain by patients requires educational interventions by health-care professionals. This is owing to the fact that in most cancer pain relief treatments, health-care professionals follow the WHO cancer pain relief guidelines that provide an appropriate type and dosage of analgesics according to the level and nature of each patient's pain.[36] In addition, patients have a misunderstanding about tolerance and addiction to opioid analgesics, and resistance to its use,[37] and the problems caused by pain are different for different patients. Under these circumstances, nurses have to give individualized education to each patient considering each patient's state of pain, knowledge and recognition about pain management, living situation, and social background.

It can be assumed the five categories for extracted attributes of self-management of cancer pain can be used as components of nursing interventions for patients with cancer pain. Self-management of cancer pain does not mean letting a patient manage the pain all by themselves; it has been shown that interaction with health-care professionals is critical. This category indicates the importance of developing a relationship between the patient and health-care professionals from a one-way supportive relationship to a partnership. Since pain is a subjective symptom, if a patient does not complain about pain, no health-care professional will be aware of it. Therefore, it is necessary for patient s to develop a good skill and relationship with a health-care professional so that they can discuss pain relief measures when they are not working well and convey their concern and negotiate how to address them. Nurses should intentionally create an opportunity to talk to patients to give them advice on how to express their expectations and requests for pain management, sometimes playing a coordinating role between a patient and the health-care professional. Decision-making to pain management can be considered as patients' willingness to manage pain by themselves and take responsibility for it. It can also be understood as the attitude of a patient trying to actively take the best pain relief measure. It is important for patients to make a decision about pain management and address it because it supports their autonomy. Therefore, nurses should support patients' decision-making by explaining the importance of taking the initiative in solving problems caused by pain. Process for solving pain-related problems is a process where patients plan, implement and evaluate a pain relief strategy, and nurses need to get involved in it continuously. The key factor in this process is self-monitoring. Self-monitoring means patients closely observe their level of pain, time of onset and duration of breakthrough pain, and time of rescue drug administration and its effect. A pain diary kept for self-monitoring can be used as a tool when a nurse talks to a patient about his/her pain and give s advice.[11,20] To improve self-management of patients, nurses have to continuously assess patients with respect to the following points: (a) How does a patient judge pain? (b) How is a patient affected by pain in daily life? (c) What kind of goal has a patient set? (d) What kind of strategies for pain relief does a patient think of and implement? (e) Is a patient implementing self-monitoring continuously? (f) Is a patient satisfied with the effect of pain relief strategies? (g) How does a patient relate with health-care professionals? Nurses can give individualized advice to each patient utilizing the results of this continuous assessment. As a result, through experiencing relief of pain and an easier life, a patient can acquire an enhanced feeling of self-efficacy that will become a driving force for solving problems at a later time. Therefore, a nurse has to share the experience of pain relief with a patient and give them feedback on how to achieve self-management so that he/she becomes aware of enhanced self-efficacy. Incorporating strategies for pain relief into daily life means patients utilize knowledge and skills of pain relief in daily life according to the change of pain. People live their life carrying out their role in paid work and/or housework, etc., finding pleasure and a reason for living. Nurses have to give advice to patients on how to utilize strategies for pain relief in daily life.

Categories of Pain relief, Well-being, and Empowerment were created for outcomes. Based on this result, it can be considered that nurses need to assess self-management of patients with cancer pain with respect not only to pain relief but also to gaining a sense of ease and satisfaction to pain relief strategies, quality of life, and empowerment.

Conclusion

In this study, five attributes, seven antecedents, and three outcomes of the concept of self-management of cancer pain were found and the process of understanding and utilizing them were suggested. The attributes of the concept of self-management of cancer pain can be used as components of nursing practice to promote self-management by patients with cancer pain. The antecedents can be used as indicators for nursing assessment, and the outcomes can be used as indicators for evaluation of nursing intervention. It was further shown that to promote patients' self-management of cancer pain in the future; it is vital to incorporate into nursing practice the elements of antecedents, attributes, and outcomes of self-management of cancer pain that were identified in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was financially supported by JSPS KAKENHI(C) Grant number JP16K12084.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

I would like to express the deepest appreciation to Prof. Kumi Suzuki at Osaka Medical College Faculty of Nursing for her supervision on writing this paper.

References

- 1.Yamagishi A, Morita T, Miyashita M, Igarashi A, Akiyama M, Akizuki N, et al. Pain intensity, quality of life, quality of palliative care, and satisfaction in outpatients with metastatic or recurrent cancer: A Japanese, nationwide, region-based, multicenter survey. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;43:503–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Patient Research. 2014. [Last 1accessed on 2017 Feb 07]. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/

- 3.Knobf MT, Cooley ME, Duffy S, Doorenbos A, Eaton L, Given B, et al. The 2014-2018 oncology nursing society research agenda. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2015;42:450–65. doi: 10.1188/15.ONF.450-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chapman RF, Smith JW, Layden TA. Elimination of cigarette smoking by punishment and self-management training. Behav Res Ther. 1971;9:255–64. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(71)90011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lorig K, Laurin J, Gines GE. Arthritis self-management. A five-year history of a patient education program. Nurs Clin North Am. 1984;19:637–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keefe FJ, Bradley LA. Behavioral and psychological approaches to the assessment and treatment of chronic pain. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1984;6:49–54. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(84)90059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kabasawa M. Nursing support in cancer -related fatigue self-management by lung cancer patients receiving postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy [in Japanese] J Seirei Soc Nurs Sci. 2012;2:10–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coward DD, Wilkie DJ. Metastatic bone pain. Meanings associated with self -report and self -management decision making. Cancer Nurs. 2000;23:101–8. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200004000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koller A, Miaskowski C, De Geest S, Opitz O, Spichiger E. Results of a randomized controlled pilot study of a self-management intervention for cancer pain. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17:284–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jahn P, Kuss O, Schmidt H, Bauer A, Kitzmantel M, Jordan K, et al. Improvement of pain-related self-management for cancer patients through a modular transitional nursing intervention: A cluster-randomized multicenter trial. Pain. 2014;155:746–54. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hochstenbach LM, Zwakhalen SM, Courtens AM, van Kleef M, de Witte LP. Feasibility of a mobile and web-based intervention to support self-management in outpatients with cancer pain. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2016;23:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughes ND, Closs SJ, Flemming K, Bennett MI. Supporting self-management of pain by patients with advanced cancer: Views of palliative care professionals. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:5049–57. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3372-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stewart C, Schofield P, Elliott AM, Torrance N, Leveille S. What do we mean by older adults' persistent pain self-management? A concept analysis. Pain Med. 2014;15:214–24. doi: 10.1111/pme.12251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodgers BL. Concept analysis: An evolutionary view. In: Rodgers BL, Knafl KA, editors. Concept Development in Nursing: Foundations, Techniques, and Applications. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2000. pp. 77–102. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aaronson NK, Mattioli V, Minton O, Weis J, Johansen C, Dalton SO, et al. Beyond treatment-psychosocial and behavioural issues in cancer survivorship research and practice. EJC Suppl. 2014;12:54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcsup.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koller A, Hasemann M, Jaroslawski K, De Geest S, Becker G. Testing the feasibility and effects of a self-management support intervention for patients with cancer and their family caregivers to reduce pain and related symptoms (ANtiPain): Study protocol of a pilot study. Open J Nurs. 2014;4:85–94. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buck R, Morley S. A daily process design study of attentional pain control strategies in the self-management of cancer pain. Eur J Pain. 2006;10:385–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chatwin J, Closs J, Bennett M. Pain in older people with cancer: Attitudes and self-management strategies. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2009;18:124–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2007.00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hochstenbach LM, Courtens AM, Zwakhalen SM, van Kleef M, de Witte LP. Self-management support intervention to control cancer pain in the outpatient setting: A randomized controlled trial study protocol. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:416. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1428-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howell D, Harth T, Brown J, Bennett C, Boyko S. Self-management education interventions for patients with cancer: A systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:1323–55. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3500-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jahn P, Kitzmantel M, Renz P, Kukk E, Kuss O, Thoke-Colberg A, et al. Improvement of pain related self-management for oncologic patients through a trans institutional modular nursing intervention: Protocol of a cluster randomized multicenter trial. Trials. 2010;11:29. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-11-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janjan N. Improving cancer pain control with NCCN guideline-based analgesic administration: A patient-centered outcome. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12:1243–9. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koller A. Inaugural Dissertation, University of Basel, Faculty of Medicine. 2012. Background. In: Testing an Intervention Designed to Support Pain Self-Management in Cancer Patients: A Mixed Methods Study. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koller A. Testing an Intervention Designed to Support Pain Self -Management in Cancer Patients: A Mixed Methods Study. Inaugural Dissertation, University of Basel, Faculty of Medicine. 2012. A Qualitative Substudy of Patients' Experiences of a Self-Management intervention for Cancer Pain and Participation in a Randomized Controlled Pilot Study. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koller A, Miaskowski C, De Geest S, Opitz O, Spichiger E. A systematic evaluation of content, structure, and efficacy of interventions to improve patients' self-management of cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;44:264–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koller A, Miaskowski C, De Geest S, Opitz O, Spichiger E. Supporting self-management of pain in cancer patients: Methods and lessons learned from a randomized controlled pilot study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lovell MR, Luckett T, Boyle FM, Phillips J, Agar M, Davidson PM, et al. Patient education, coaching, and self-management for cancer pain. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1712–20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.4850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCorkle R, Ercolano E, Lazenby M, Schulman-Green D, Schilling LS, Lorig K, et al. Self-management: Enabling and empowering patients living with cancer as a chronic illness. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:50–62. doi: 10.3322/caac.20093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oliver JW, Kravitz RL, Kaplan SH, Meyers FJ. Individualized patient education and coaching to improve pain control among cancer outpatients. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2206–12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.8.2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Risendal BC, Dwyer A, Seidel RW, Lorig K, Coombs L, Ory MG, et al. Meeting the challenge of cancer survivorship in public health: Results from the evaluation of the chronic disease self-management program for cancer survivors. Front Public Health. 2014;2:214. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vallerand AH, Musto S, Polomano RC. Nursing's role in cancer pain management. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2011;15:250–62. doi: 10.1007/s11916-011-0203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoshizawa K, Kimoto T, Hamada K, Fukuda K, Fujioka H, Matsumaru Y, et al. Evaluation of the guidelines for management of opioid analgesics used for cancer inpatients [in Japanese] J Jpn Soc Hosp Pharm. 2008;44:1053–5. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oene I, Saito M, Nawata S, Kikuchi M, Urasaki T, Iwasaki Y, et al. Development and evaluation of a new self-management system of administration of narcotic drugs for medical use in hospitalized patients [in Japanese] Palliat Care Res. 2010;5:114–26. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shirayoshi H, Matsuda K, Saigo O, Nakajima H, Onishi Y, Harada Y, et al. A survey of healthcare professionals' attitudes towards the implementation and status of self-management of patients requiring opioid rescue therapy [in Japanese] J Jpn Soc Hosp Pharm. 2012;48:329–35. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hiraoka R, Sato R. Independent grappling with pain management of cancer patients [in Japanese] J Jpn Soc Cancer Nurs. 2012;26:23–33. [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1996. Cancer Pain Relief. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reid CM, Gooberman-Hill R, Hanks GW. Opioid analgesics for cancer pain: Symptom control for the living or comfort for the dying? A qualitative study to investigate the factors influencing the decision to accept morphine for pain caused by cancer. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:44–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]