Abstract

Context:

Studying the link between prolactin and autoimmunity has gained much ground over the past years. Its role played in alopecia areata (AA) is not clear yet, as previous reports yielded controversial results.

Aims:

This study aimed to measure the serum level of prolactin and to detect the expression of its receptor in AA, in an attempt to highlight its possible role in the pathogenesis of this disease.

Subjects and Methods:

A case-control study of 30 AA patients and 20 controls from outpatient clinic were undertaken. Every patient was subjected to history taking and clinical examination to determine the severity of alopecia tool (SALT) score. Blood samples were taken from patients and controls to determine the serum prolactin level. Scalp biopsies were obtained from the lesional skin of patients and normal skin of controls for assessment of the prolactin receptor.

Statistical Analysis:

Depending upon the type of data, t-test, analysis of variance test, Chi-square, receiver operator characteristic curve were undertaken.

Results:

On comparing the serum prolactin level between patients and controls, no significant difference was found, while the mean tissue level of prolactin receptor was significantly higher in patients than in controls. In patients, a significant positive correlation was found between the prolactin receptor and the SALT score.

Conclusions:

Prolactin plays a role in AA, and this role is probably through the prolactin receptors rather than the serum prolactin level.

Keywords: Alopecia areata, cell-mediated immunity, immunology

What was known?

Human scalp hair follicles are a target and a source of prolactin. Prolactin acts as a promoter of apoptosis-induced hair follicle regression.

Introduction

Alopecia areata (AA) is a form of nonscarring hair loss affecting anagen hair follicles. Its exact cause is not known, but the current body of evidence supports an autoimmune origin and strong genetic contribution, further modified by unknown environmental influences.[1]

Prolactin is a pituitary peptide hormone that is known to modulate immune responses.[2] It is generated and secreted by the lactotroph cells of the anterior pituitary gland,[3,4] acts systemically as a hormone, and locally as a cytokine.[5] Prolactin and prolactin receptor (PRLR) expression has now been demonstrated in several cutaneous cell populations, including keratinocytes, fibroblasts, sweat glands, sebaceous glands, and human scalp hair follicles.[2] It is involved in the activation and differentiation of thymic epithelial cells, thymocytes, lymphocytes, and macrophages. It also operates as part of a neuroendocrine–immune network by stimulating the release of specific cytokines.[6] It is one of the major hormonal signals that are immediately upregulated on psychoemotional and physical stress.[7]

Studying the link between prolactin and autoimmunity has gained much ground over the past years, with prolactin being investigated in several autoimmune diseases as systemic lupus erythematosis, systemic sclerosis, psoriasis vulgaris, Sjogren's disease, and AA.[8]

The role played by prolactin in AA is not clear yet, as previous reports yielded controversial results,[9,10,11,12] and one study showed no change in its level following therapy.[12] Hence, the current study was conducted to measure the serum level of prolactin, as well as to detect the expression of its receptor in AA patients, in an attempt to verify their possible role in the pathogenesis of this disease.

Subjects and Methods

This case–control study was carried out on 30 patients with AA and 20 healthy volunteers serving as controls, recruited from Kasr Al Ainy Dermatology Outpatient Clinic. The study was approved by the Dermatology Research Ethical Committee (Derma REC) of the Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University. A written informed consent was signed by each patient and control. Inclusion criteria included new cases of AA or recurrent cases who did not receive any treatment at least 2 months before the study. Patients <18 year old and those with current/history of any dermatological and/or other autoimmune disorders were excluded from this study. Pregnant and lactating females as well as patients on medications known to affect prolactin level were also excluded.

Every patient was subjected to history taking including personal data, history of the present illness, and clinical examination to determine the extent of AA using the severity of alopecia tool (SALT) score.[13] This is a global severity score created by the combination of extent and density of scalp hair loss. It determines the amount of terminal hair loss in each of the four scalp's views then adding these together with a full score of 100%.

A 3 ml blood sample was withdrawn from all individuals to determine the serum prolactin level. A 4 mm punch scalp biopsy was obtained from the lesional skin of the patients and from the normal skin “in the occipital area” of controls for assessment of the prolactin receptor.

Detection of serum prolactin levels and expression of its receptor

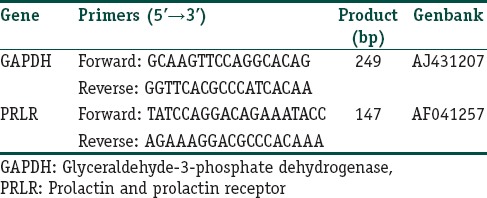

The prolactin level was measured in serum sample of each individual by using ELISA kit which based on the principle of Solid Phase Sandwich ELISA technique (Quantikine, USA), expressed in ng/ml. Total RNA was extracted from the skin biopsy using RNA extraction kit provided by Qiagen extraction kit. RNA purity and quantity were measured by Nanodrop. Two sets of primers were used for amplification of PRLR and Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as housekeeping gene [Table 1]. The polymerase chain reaction products were quantitated by using a quantitation kit (from Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA).

Table 1.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction primer sequences and polymerase chain reaction product size for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, prolactin and prolactin receptor

Statistical analysis

All statistical calculations were done using computer programs SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Science; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) version 15 for Microsoft Windows. Data were statistically described in terms of range, mean ± standard deviation, frequencies (number of cases), and percentages when appropriate. Comparison of numerical variables between the study groups was done using Student's t-test for independent samples in comparing 2 groups and one-way analysis of variance test when comparing more than 2 groups. For comparing categorical data, Chi-square test was performed. Exact test was used instead when the expected frequency is <5. Accuracy was represented using the terms sensitivity and specificity. Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to determine the optimum cutoff value. Correlation between various variables was done using Pearson moment correlation equation for linear relation. P <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The study included 30 patients; 16 (53.3%) males and 14 (46.7%) females with AA, whose age ranged between 18 and 46 years with a mean of 29.4 ± 8.82 years. The disease duration ranged between 1 month and 96 months, with a mean of 16.63 ± 20.38 months. All the patients had scalp AA with variable extent of lesions. The SALT score ranged from 3 to 70 with a mean of 17.87 ± 16.41. Seventeen patients (56.7%) had associated precipitating factor in the form of psychic stress.

Twenty individuals (9 [45%] males and 11 [55%] females) whose age ranged between 18 and 45 years with a mean of 29.30 ± 8.23 years served as controls. There was no significant difference between patients and controls in terms of age and sex distribution (P =0.96 and 0.56, respectively).

Serum prolactin level and tissue expression of prolactin receptor

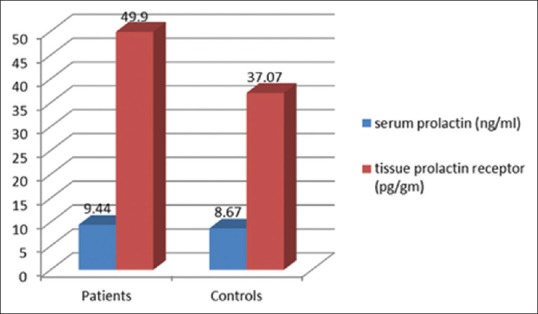

On comparing the serum prolactin level between the patient and the control groups, no significant statistical difference was found (P =0.56). Among the patients, the level of serum prolactin ranged between 3.3 and 22.1 ng/ml with a mean of 9.44 ± 4.90 ng/ml whereas within the control group, the level of serum prolactin ranged between 2.2 and 18.2 ng/ml with a mean of 8.67 ± 4.07 ng/ml [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Comparison of the mean serum prolactin level and mean tissue prolactin receptor level in patients versus controls

On the other hand, the mean tissue level of prolactin receptor was significantly higher in the lesional skin of patients (18.1–82.1 pg/g with a mean of 49.90±18.29 pg/g) compared to the normal skin of controls (10.7–69.9 pg/ml with a mean of 37.07±19.30 pg/g) (P =0.02) [Figure 1].

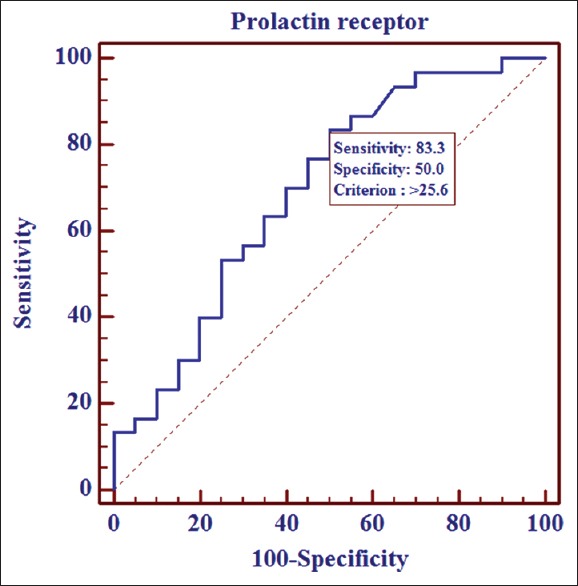

To determine the cutoff limit for prolactin receptor level that would differentiate between normal and AA skin, we performed ROC analysis. A level of 25.6 pg/ml was determined as the cutoff point, with a sensitivity of 83.3% and specificity of 50% (95% CI: 0.54–0.85, P =0.02) [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Receiver operator characteristic curve for the level of prolactin receptors

A statistically significant positive correlation was found between the tissue level of prolactin receptor in the patients and their SALT score (r =0.36, P =0.045). No statistically significant correlation was found between the tissue level of prolactin receptor and the disease duration (r =0.31, P =0.09).

Discussion

The answer provided by the current study to the proposed question around the possible role played by prolactin in AA is that this role is most probably played through the prolactin receptor rather than serum prolactin level itself. This was evident through the detection of a significantly increased expression of prolactin receptor in the patient group in comparison to control, with no significant difference in the prolactin serum level between the two groups.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on the importance of prolactin receptor in AA. The findings of the present study allowed us to hypothesize that the role of prolactin in AA could simulate that of androgen in female pattern hair loss where several studies documented normal serum androgen level with increased number and sensitivity of androgen receptors in such patients.[14,15]

The absence of a significant difference in the serum level of prolactin in patients in comparison to controls detected in the current study comes in accordance with that documented by two previous studies.[9,10] Accordingly, both studies denied a possible role of prolactin in the pathogenesis of AA, something we could not state owing to the further studying of the prolactin receptor. On the contrary, two other studies documented a significantly elevated level of serum prolactin in AA patients compared to controls,[11,12] and that serum prolactin level was significantly correlated with disease severity.[11]

In the current study, we postulate that the role of prolactin in AA could be explained by the increased number of prolactin receptor and thereby increased influence of prolactin on such patients.

Prolactin and AA could be connected with each other through various immunological pathways. Prolactin for one promotes the survival, proliferation, and differentiation of CD4− and CD8− thymocytes into CD4+ and CD8+ cells.[16] These CD4+ and CD8+ cells are clustered at a high density around the anagen hair bulb in AA.[17] The immune privilege collapse that takes place in AA induces expression of MHC class I molecules on follicular cells, leading to the induction of both CD8 positive cytotoxic cells and MHC class II molecules, leading to induction of CD4 helper, and then the downstream autoimmune phenomenon with generation of autoreactive T-cells.[18]

Moreover, prolactin activates the proliferation and lytic function of the natural killer cells.[19] These natural cells are highly active in patients with AA where hair follicles have a decreased capacity to suppress their undesired cell activity.[20] Many perifollicular CD56+ natural killer (NK) cells with high expression of the NK cell activating receptor NKG2D are present in AA lesions but not in normal scalp.[17] At the same time, the ligand for NKG2D, MHC class I chain-related protein, was found to be expressed at very high levels in the proximal outer root sheath, the dermal papilla, and the connective tissue sheath of AA hair follicles.[21] The immune privilege hair follicle collapse that occurs in AA leads to NKG2D+ NK cell attack which can recognize autoantigens that result in apoptotic responses and hair loss.[22]

Add to this, the ability of prolactin to stimulate the synthesis and release of immunomodulating cytokines and lymphocyte-activating factors, especially IL-1 which was found to be highly expressed in patients with AA may have a role in causing damage to the hair follicle.[23] Studies have shown that IL-1 is a very potent inducer of hair loss and a significant human hair growth inhibitor in vitro.[24] In human scalp, areas affected by AA have an excessive expression of IL-1β particularly at the early stages of the disease, while susceptibility to the disease and severity are determined by polymorphisms of the IL-1α.[25] In addition to this, prolactin increases the synthesis of IFN-γ,[26] which is the main cytokine known to be aberrantly expressed in AA through a CD4+ Th1-mediated response. Among several actions, it deprives dermal papilla cells from their ability to maintain anagen hair growth.[27] Moreover, prolactin also increases the synthesis of TNF-α[28] which plays a role in the pathogenesis of AA.[29]

From all the abovementioned points, we can assume the relation between prolactin and AA being explained by the positive result that the present study has reached. The detection of a significant positive correlation between prolactin receptor and the SALT score indicates that the prolactin receptor is actually related to the disease severity. However, no similar correlation could be detected between the receptor and the disease duration denying their role in the disease chronicity.

Finally, we can conclude that prolactin plays a role in AA and that this role is most probably through the prolactin receptor rather than serum prolactin itself. Moreover, the prolactin receptor expression is positively related to the disease severity.

This study reopens the doors for a deeper understanding of AA with highlighting a positive role played by prolactin in its pathogenesis, evident by the significant increase in prolactin receptor expression in AA. In the last few years, prolactin receptor antagonists have been widely incorporated in the treatments of different diseases including hyperprolactinemia, breast cancer, and prostatic cancer.[30] The use of prolactin receptor antagonists may be of beneficial therapeutic effect in AA as well, especially in severe cases, a suggestion that needs further elaborative work.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

Prolactin plays a role in AA through their receptors rather than serum prolactin itself.

References

- 1.Rodriguez TA, Fernandes KE, Dresser KL, Duvic M National Alopecia Areata Registry. Concordance rate of alopecia areata in identical twins supports both genetic and environmental factors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:525–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foitzik K, Krause K, Conrad F, Nakamura M, Funk W, Paus R, et al. Human scalp hair follicles are both a target and a source of prolactin, which serves as an autocrine and/or paracrine promoter of apoptosis-driven hair follicle regression. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:748–56. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freeman ME, Kanyicska B, Lerant A, Nagy G. Prolactin: Structure, function, and regulation of secretion. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:1523–631. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.4.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ben-Jonathan N, LaPensee CR, LaPensee EW. What can we learn from rodents about prolactin in humans? Endocr Rev. 2008;29:1–41. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chilton BS, Hewetson A. Prolactin and growth hormone signaling. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2005;68:1–23. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(05)68001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ben-Jonathan N, Hugo ER, Brandebourg TD, LaPensee CR. Focus on prolactin as a metabolic hormone. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2006;17:110–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arck PC, Slominski A, Theoharides TC, Peters EM, Paus R. Neuroimmunology of stress: Skin takes center stage. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:1697–704. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shelly S, Boaz M, Orbach H. Prolactin and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;11:A465–70. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gönül M, Gül U, Cakmak S, Kilinç C, Kilinç S. Prolactin levels in the patients with alopecia areata. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1343–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burak A, Erol C, Yaşargul D. Serum prolactin levels in patients with alopecia areata. J Turk Acad Dermatol. 2012;6:1264a1. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elsherif NA, Elsherif AI, El-Dibany SA. Serum prolactin levels in dermatological diseases: A case-control study. J Dermatol Dermatol Surg. 2015;19:104–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganzetti G, Simonetti O, Campanati A, Giuliodori K, Scocco V, Brugia M, et al. Osteopontin: A new facilitating factor in alopecia areata pathogenesis? Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2015;23:19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olsen EA, Hordinsky MK, Price VH, Roberts JL, Shapiro J, Canfield D, et al. Alopecia areata investigational assessment guidelines – Part II. National alopecia areata foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:440–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaufman KD. Androgens and alopecia. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;198:89–95. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00372-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herskovitz I, Tosti A. Female pattern hair loss. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;11:e9860. doi: 10.5812/ijem.9860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carreño PC, Sacedón R, Jiménez E, Vicente A, Zapata AG. Prolactin affects both survival and differentiation of T-cell progenitors. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;160:135–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiarini C, Torchia D, Bianchi B, Volpi W, Caproni M, Fabbri P, et al. Immunopathogenesis of folliculitis decalvans: Clues in early lesions. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;130:526–34. doi: 10.1309/NG60Y7V0WNUFH4LA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilhar A, Paus R, Kalish RS. Lymphocytes, neuropeptides, and genes involved in alopecia areata. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2019–27. doi: 10.1172/JCI31942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mavoungou E, Bouyou-Akotet MK, Kremsner PG. Effects of prolactin and cortisol on natural killer (NK) cell surface expression and function of human natural cytotoxicity receptors (NKp46, NKp44 and NKp30) Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;139:287–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02686.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gasser S, Raulet DH. Activation and self-tolerance of natural killer cells. Immunol Rev. 2006;214:130–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ito T, Meyer KC, Ito N, Paus R. Immune privilege and the skin. Curr Dir Autoimmun. 2008;10:27–52. doi: 10.1159/000131412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ito T. Recent advances in the pathogenesis of autoimmune hair loss disease alopecia areata. Clin Dev Immunol. 2013;2013:348546. doi: 10.1155/2013/348546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarkar DK, Chaturvedi K, Oomizu S, Boyadjieva NI, Chen CP. Dopamine, dopamine D2 receptor short isoform, transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta1, and TGF-beta type II receptor interact to inhibit the growth of pituitary lactotropes. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4179–88. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoffmann R, Happle R. Does interleukin-1 induce hair loss? Dermatology. 1995;191:273–5. doi: 10.1159/000246567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffmann R. The potential role of cytokines and T cells in alopecia areata. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:235–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.jidsp.5640218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biswas R, Roy T, Chattopadhyay U. Prolactin induced reversal of glucocorticoid mediated apoptosis of immature cortical thymocytes is abrogated by induction of tumor. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;171:120–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arca E, Muşabak U, Akar A, Erbil AH, Taştan HB. Interferon-gamma in alopecia areata. Eur J Dermatol. 2004;14:33–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang L, Hu Y, Li X, Zhao J, Hou Y. Prolactin modulates the functions of murine spleen CD11c-positive dendritic cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:1478–86. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Philpott MP, Sanders DA, Bowen J, Kealey T. Effects of interleukins, colony-stimulating factor and tumour necrosis factor on human hair follicle growth in vitro: A possible role for interleukin-1 and tumour necrosis factor-alpha in alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:942–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1996.d01-1099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goffin V, Touraine P. The prolactin receptor as a therapeutic target in human diseases: Browsing new potential indications. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2015;19:1229–44. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2015.1053209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]