Abstract

Background/Purpose:

Helicobacter pylori infection has been suggested as a culprit of various extragastrointestinal (GI) disorders. It is debatable whether H. pylori infection exacerbates or triggers the pathogenesis of psoriasis. This meta-analysis aimed to explore the association between psoriasis and H. pylori infection.

Materials and Methods:

A comprehensive search of the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases was performed from inception through October 2017. The inclusion criterion was observational studies evaluating the association between psoriasis and H. pylori infection. The pooled odds ratio (OR) of H. pylori infection and their 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated using a random-effects meta-analysis to compare risk between psoriasis patients and controls. The between-study heterogeneity of effect-size was quantified using the Q statistic and I2.

Results:

Data were extracted from nine observational studies involving 1546 individuals. Pooled result demonstrated an increased H. pylori infection in psoriasis compared with controls (OR=1.58; 95% CI: 1.02–2.46, P =0.04, I2=64%). Subgroup analysis showed an increased risk of H. pylori infection in psoriasis measured with H. pylori IgG enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (OR=3.11; 95% CI: 1.85–5.20, P <0.01, I2=10%) but not active infection measured with urea breath test (OR=0.88; 95% CI: 0.61–1.27, P =0.49, I2=0%).

Conclusion:

This meta-analysis has shown an increased H. pylori infection in patients with psoriasis. H. pylori infection in the past could play a role in the abnormal immunological cascade in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Further studies to elucidate the inflammatory response in the pathogenesis of psoriasis are warranted.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, meta-analysis, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis

What was known?

Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with an increased risk of various extragastrointestinal disorders. It is debatable whether H. pylori infection exacerbates or triggers the pathogenesis of psoriasis.

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori infection is a common infection worldwide, especially in the developing and underdeveloped countries. The prevalence of H. pylori infection is strongly correlated with age and socioeconomic status. Most people with H. pylori infection are asymptomatic, while 15%–20% of patients will develop gastric and duodenal ulcers, gastric adenocarcinomas, and lymphomas.[1] H. pylori infection has been proposed as a culprit of various extragastrointestinal (GI) tract disorders. The proposed mechanism of H. pylori infection causing extra GI conditions is due to a significant local inflammatory response at the gastric mucosa, which could potentially produce a systemic effect because of the alteration of systemic inflammatory mediators.[1] Few studies have found that H. pylori seropositivity is associated with elevated C-reactive protein level and platelet activation factors;[2,3] other studies reported that H. pylori infection activates the inflammatory process through the uncontrolled release of interleukins.[4,5] Nevertheless, studies on the causal relationship between dermatological disorders such as rosacea, chronic urticaria, alopecia areata, psoriasis and H. pylori infection have also been reported.

Psoriasis is an inflammatory disease, probably of autoimmune etiology, that is typically characterized by erythematous papules and plaques with silvery scales. Genetic predisposition plays a leading role in the development of psoriasis; however, the associations of smoking, alcohol consumption, vitamin D deficiency, obesity, and high body mass have also been reported in the literature.[6,7,8] There is also growing evidence that suggests infections can trigger the development of psoriasis through the binding of superantigens on the T-cell receptor and the major histocompatibility system that is expressed on the antigen-presenting cells and activates the CD4+ T cells eventually.[9] H. pylori infection is hypothesized as one of the microbial infections that could exacerbate psoriasis through the mechanisms above. Despite that, there are conflicting reports about the association. So, we undertook this systematic review and meta-analysis to explore the relation between psoriasis and H. pylori infection.

Materials and Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted and reported according to the Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology statement.[10] This review was registered in PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42017078920).

Search strategy

Three authors (WCY, AS, SU) independently searched published studies indexed in MEDLINE and EMBASE from date of inception to October 2017. References of all selected studies were also examined. The following main search terms were used: psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, H. pylori. The full search terms used are detailed in the Supplemental Material and Methods.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This review included all published observational studies including cross-sectional, prospective cohort, retrospective cohort, and case–control studies that assessed the association between psoriasis and H. pylori infection. Reviews, case reports, and abstracts were excluded because their quality could not be ascertained.

We included studies that recruited participants from the general population or used data from medical records from healthcare facilities. Participants were adults aged 18 year or older with any type of psoriasis (plaque, guttate, pustular, inverse, erythrodermic, or psoriatic arthritis) or healthy individuals. The primary outcome, diagnosis of H. pylori infection, was from the comparison between patients who were diagnosed with psoriasis and participants who did not have psoriasis. The odds ratios (ORs), relative risks (RR), hazard ratios (HR), or the number of participants with outcome were extracted. The H. pylori infection was diagnosed by H. pylori IgG enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test, urea breath test, or stool antigen test.

Data extraction

All authors independently reviewed titles and abstracts of all citations that were identified. After abstracts were reviewed, data comparisons between the three investigators were conducted to ensure completeness and reliability. The inclusion criteria were independently applied to all identified studies. Differing decisions were resolved by consensus.

Full-text versions of potentially relevant papers identified in the initial screening were retrieved. Data concerning study design, the source of information, participant characteristics, assessment of psoriasis and H. pylori infection were independently extracted. We contacted the authors of the original reports to request any unpublished data. If the authors did not reply, we used the available data for our analysis.

Assessment of bias risk

A subjective evaluation of the methodological quality of observational studies was performed by all three authors using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale,[11] which is a quality assessment tool for nonrandomized studies. It uses a “star system” based on three major perspectives: the selection of the study groups (0–4 stars, or 0–5 stars for cross-sectional studies), the comparability of the groups by controlling for important and additional relevant factors (0–2 stars), and the ascertainment of outcome of interest or exposure (0–3 stars). A total score of 3 or less was considered poor, 4–6 was considered moderate, and 7–10 was deemed high quality. We excluded studies from our meta-analysis if they had poor quality. Discrepant opinions between authors were resolved by consensus.

Statistical analysis

We performed a meta-analysis of the included studies using Review Manager 5.3 software from The Cochrane Collaboration to generate forest plot and Comprehensive Meta-Analysis 3.3 software from Biostat, Inc (Biostat, Inc., Englewood, NJ, USA) to create funnel plot and perform Egger's regression test. We calculated pooled effect estimate of incidence or prevalence of H. pylori infection with 95% confidence interval (CI) comparing between psoriasis and control groups using a random effects model. We used effect size (OR, HR, and RR) from univariate or, if available, multivariate models with confounding factors (age and gender) adjusted in each study. We excluded studies from meta-analysis and only presented the result with narrative description (qualitative analysis) when there were not sufficient data available for calculating pooled effect size. The heterogeneity of effect estimates across these studies was quantified using the Q statistic and I2 (P <0.10) was considered statistically significant. The Q statistic compared the observed between-study dispersion and expected dispersion of the effect size and was expressed in P-value for statistical significance. An I2 is the ratio of actual heterogeneity to total observed variation.[12] A value of 0% indicates no observed heterogeneity, and higher values show increasing heterogeneity.[12] Publication bias was assessed using funnel plot, Egger's regression test, and its implications with the trim and fill method.[13]

Results

Description of included studies

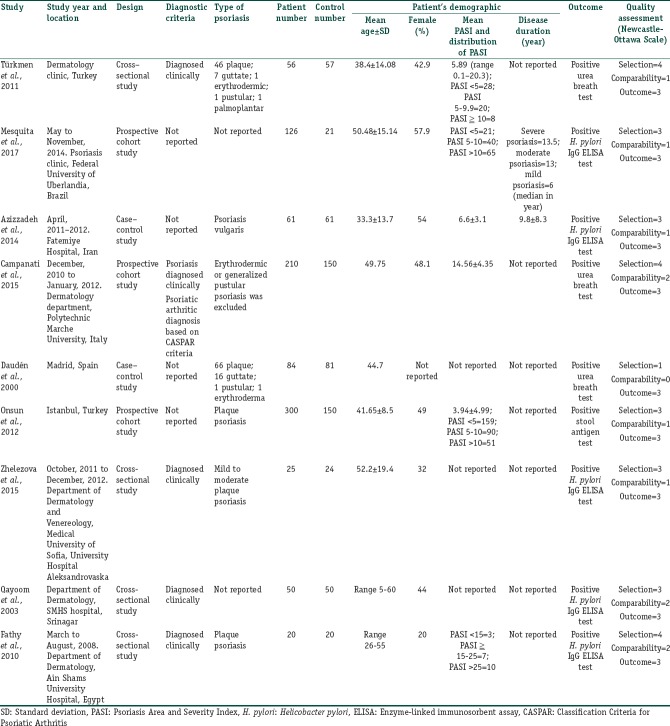

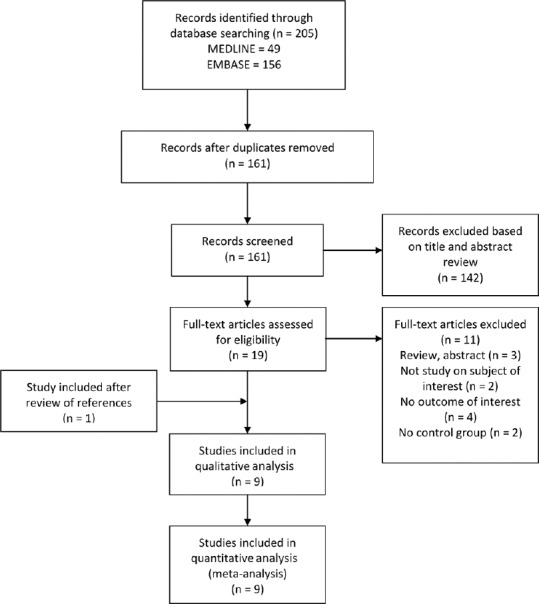

The initial search yielded 161 articles [Figure 1]; 142 articles were excluded based on the title and abstract review. A total of 19 articles underwent full-length review. Eleven articles were excluded (3 review or abstract articles; two articles had no control group; 4 articles did not report the outcome of interest; two articles were not studied on the subject of interest). One study was included after reviewing the references of included studies. Data were extracted from nine studies involving a total of 1,546 participants for qualitative analysis. The included studies varied in study location, sample size, and source of data. Five studies used H. pylori ELISA test; three studies used urea breath test, and one study used stool antigen test as H. pylori diagnostic method. Five studies [14,15,16,17,18] have excluded participants with GI complaints or diseases. Fathy et al. is the only study [14] that mentioned about the exclusion of other autoimmune and skin disorders. Daudén et al.[19] did not report the inclusion or exclusion of participants with GI symptoms or other autoimmune diseases. Whereas Campanati et al.[20] included participants with GI complaints, the authors did not compare the number of patients and controls with different GI symptoms. The authors did report that the percentage of epigastric pain (27.5% vs. 13.9%), and heartburn (25% vs. 10.8%) were higher in psoriasis patients with H. pylori positive than those patients with H. pylori negative on urea breath test. No difference in symptoms of dyspepsia, bloating, diarrhea, constipation, and weight loss in both H. pylori positive and negative psoriasis patient groups.[20] Türkmen et al.[21] included participants with GI symptoms; however, there was no statistically significant difference in between psoriasis and control groups. The number of participants with different GI symptoms in each group was also not reported.[21] The characteristics of the nine extracted studies included in this review were outlined in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow of search methodology and selection process

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of included observational studies

Meta-analysis results

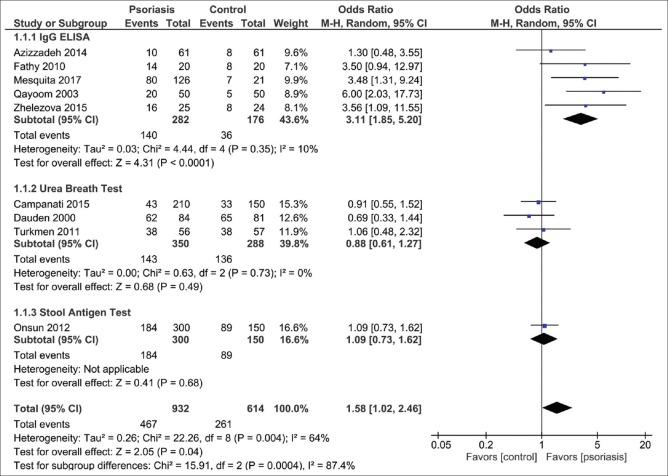

The pooled result demonstrated an increased H. pylori infection in psoriasis compared with controls (OR=1.58; 95% CI: 1.02–2.46, P =0.04, I2=64%) [Figure 2]. Subgroup analysis showed a statistically significant increase of H. pylori infection in psoriasis patients tested with H. pylori IgG ELISA test (OR=3.11; 95% CI: 1.85-5.20, P <0.01, I2=10%) but not with urea breath test (OR=0.88; 95% CI: 0.61–1.27, P =0.49, I2=0%).

Figure 2.

Forest plot assessing the odd of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with and without psoriasis. CI: Confidence interval

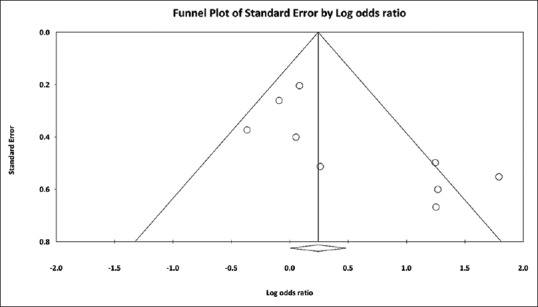

Publication bias

To investigate potential publication bias, we examined the funnel plot of the included studies in the meta-analysis of the H. pylori infection [Figure 3]. The vertical axis represents study size (standard error) while the horizontal axis represents the difference in means. From this plot, publication bias exists because there was an asymmetrical distribution of studies with a statistically significant Egger's test result (P =0.03). Using the trim and fill methods for potential missing data, there was a difference of the imputed OR and its 95% CI (OR=1.24; 95% CI: 0.77–2.00).

Figure 3.

Funnel plot showing studies reporting Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with and without psoriasis

Discussion

This systematic review has shown an increased H. pylori infection in patients with psoriasis that was mainly driven by the infection detected with H. pylori IgG ELISA test. Since the ELISA test only detects host exposure to the bacterium regardless of current or previous infection while both urea breath test and stool antigen test detect ongoing infection, our result implies that H. pylori infection in the past could be the culprit of the abnormal immunological cascade in the pathogenesis of psoriasis.

Few studies [17,19,20,21] have not found an increased prevalence of active H. pylori infection in psoriasis population using urea breath test or stool antigen study, yet Onsun et al.[17] and Campanati et al.[20] demonstrated psoriasis patients with H. pylori infection have a higher Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score. Mesquita et al.[16] and Fathy et al.[14] described a higher percentage of H. pylori infection among patients with severe psoriasis compared to patients with mild or moderate disease. Onsun et al.[17] and Campanati et al.[20] also reported a significant improvement in PASI score in patients with H. pylori infection who received the combination of antibiotic and psoralen + ultraviolet A therapy,[20] or antibiotic and acitretin therapy.[17] In addition, psoriasis patients with H. pylori infection who received H. pylori treatment alone have shown more improvement than those patients receiving acitretin alone, thus leading to the conclusion of H. pylori contributing to the severity of the disease. On the contrary, despite Campanati et al. concluded a significant improvement of PASI score in the infected patients than the noninfected patients after eradication of H. pylori, the authors compared the infected patients at week 5 after receiving combination therapy with the uninfected patients at week 0 who had not received any treatment. Thus, the observed improvement of PASI score could be merely from psoralen + ultraviolet A therapy and not from the effect of H. pylori eradication therapy. Nonetheless, few case studies reported the improvement of psoriasis after treating the H.pylori infected patients. However, this contradicts the result of Dauden et al. because they have not discovered an improvement of psoriasis after eradication of H.pylori infection. Two studies [14,18] found a positive correlation between the value of seropositivity with the severity of psoriasis and a higher prevalence of H. pylori infection in patients with psoriasis than in those without psoriasis. Mesquita et al.[16] revealed that negative H. pylori serology correlates with a milder picture of psoriasis. In contrast, Azizzadeh et al.[15] did not find a significant relationship between H. pylori infection and psoriasis or a correlation between H. pylori IgG level and PASI score.

Based on a higher past infection rate of H. pylori in psoriasis from our study result, and the association between current H. pylori infection with higher PASI score, H. pylori past infection might play a role in triggering psoriasis while ongoing infection exacerbates psoriasis.[5,25] The proposed pathogenesis of H. pylori contribution to the severity of psoriasis could be the systemic effect from a severe localized gastric mucosa inflammation with a robust inflammatory response.[26]H. pylori induces an immune response with macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes infiltrating the gastric mucosa. This immune response is similar to the reaction between hemolytic streptococcus Group A antigens and host proteins which triggers both humoral and cell-mediated immune reactions.[5] Gastric mucosal permeability to food antigens, immunomodulation, autoimmune mechanism, and impairment of vascular integrity might be involved in the systemic effects of H. pylori infection.[27,28,29] Other studies have also linked the improvement of various dermatological diseases, such as chronic urticaria, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, rosacea, and Behcet syndrome to the eradication of H. pylori.[16,20] Besides H. pylori infection, other micro-organisms such as Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, viruses, and fungi, have been connected to the exacerbation of psoriasis.[17]

There are few limitations in our study. Although our study has shown an increased risk of H. pylori infection in psoriasis patients, the 1.6-fold increased risk may not be clinically significant or relevant. We were unable to stratify the H. pylori infection prevalence rate based on the severity of psoriasis. Our study also did not include participants aged less than 18 year old except Qayoom et al.[30] Nevertheless, the research on children population failed to reveal a higher prevalence of H. pylori infection in children with psoriasis. Fabrizi et al.[31] reported 10% positive urea breath test in children with psoriasis versus 17% positive result in children without skin diseases. The method of detecting H. pylori infection also will affect the reported prevalence of H. pylori infection in the patient population.[32] Especially for serological tests, the cutoff of serological tests depends on the prevalence of H. pylori infection in the general population of their respective areas. Due to the antigenic variable strains of H. pylori infection in different geographical regions, it is also recommended to use the local strains when preparing the detection kits. Alternatively, strains sharing the common antigens globally or strains pooling from different geographical regions should be used.[33] There are numerous serological tests in the market, but it is more useful to evaluate H. pylori infection in children, especially in a good sanitary condition and low prevalence of H. pylori infection, as compared to adults. The sensitivity and specificity of serological tests have been reported to be 85% and 79%, respectively. In contrast, urea breath test has a sensitivity of 75% to 100%, and specificity of 77% to 100%, and fecal antigen test has a sensitivity of 67% to 100% and specificity of 61% to 100%.[33] Therefore, the serological test is not the recommended diagnostic test as compared to urea breath test and fecal antigen test to diagnose H. pylori active infection because the titer levels can remain elevated for long after treatment and the seropositivity rate relies on the local H. pylori prevalence rate, bacterial strains, and positive cutoff of the detection kits.[33] Hence, we concluded that H. pylori exposure at certain point in life might have triggered the abnormal autoimmune cascade in psoriasis patients. Finally, the reason of H. pylori -infected patients having more severe psoriasis than uninfected patients could be from the use of systemic therapy that increases the risk of H. pylori infection instead of H. pylori infection per se worsens psoriasis.[20]

Conclusion

This meta-analysis has shown an increased H. pylori infection in patients with psoriasis. H. pylori infection in the past may play a role in the abnormal immunological cascade in the pathogenesis of psoriasis, while an ongoing H. pylori infection may exacerbate psoriasis. Therefore, psoriasis patients with GI symptoms or high PASI score should be screened for H. pylori infection by using urea breath test or fecal antigen test, which provides more accurate diagnosis of an active infection. Alternatively, a two-step diagnostic approach with a validated serological tests followed by urea breath test or fecal antigen test could be used if there is a limitation in logistics or health-care resources. Further studies with the use of urea breath test or fecal antigen test to elucidate the inflammatory response in the pathogenesis of psoriasis triggered by active H. pylori infection are warranted.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

There is an approximately 1.6-fold increased risk of Helicobacter pylori infection being detected in patients with psoriasis which was mainly driven by previous H. pylori infection.

References

- 1.Leontiadis GI, Sharma VK, Howden CW. Non-gastrointestinal tract associations of Helicobacter pylori infection. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:925–40. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.9.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krueger JG, Bowcock A. Psoriasis pathophysiology: Current concepts of pathogenesis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(Suppl 2):ii30–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.031120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nestle FO, Kaplan DH, Barker J. Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:496–509. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganzetti G, Campanati A, Offidani A. Alopecia areata: A possible extraintestinal manifestation of Crohn's disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:962–3. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hernando-Harder AC, Booken N, Goerdt S, Singer MV, Harder H. Helicobacter pylori infection and dermatologic diseases. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:431–44. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2009.0739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ricceri F, Pescitelli L, Tripo L, Prignano F. Deficiency of serum concentration of 25-hydroxyvitamin D correlates with severity of disease in chronic plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:511–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li W, Han J, Choi HK, Qureshi AA. Smoking and risk of incident psoriasis among women and men in the United States: A combined analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175:402–13. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lebwhol M, Callen JP. Obesity, smoking, and psoriasis. JAMA. 2006;295:208–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campanati A, Ganzetti G, Di Sario A, Benedetti A, Offidani A. Insulin resistance, serum insulin and HOMA-R. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:673. doi: 10.1007/s00535-013-0769-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: A proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–5. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sterne JA, Egger M. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: Guidelines on choice of axis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:1046–55. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fathy G, Said M, Abdel-Raheem SM, Sanad H. Helicobacter pylori Infection: A possible predisposing factor in chronic plaque-type psoriasis. J Egypt Women Dermatol Soc. 2010;7:39–43. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azizzadeh M, Nejad ZV, Ghorbani R, Pahlevan D. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and psoriasis. Ann Saudi Med. 2014;34:241–4. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2014.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mesquita PM, Filho Diogo A, Jorge MT, Berbert AL, Mantese SA, Rodrigues JJ, et al. Relationship of Helicobacter pylori seroprevalence with the occurrence and severity of psoriasis. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:52–7. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20174880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Onsun N, Arda Ulusal H, Su O, Beycan I, Biyik Ozkaya D, Senocak M, et al. Impact of Helicobacter pylori infection on severity of psoriasis and response to treatment. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:117–20. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2011.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhelezova G, Yocheva L, Tserovska L, Mateev G, Vassileva S. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori seropositivity in patients with psoriasis. Probl Inf Parasit Dis. 2015;43:13–7. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daudén E, Vázquez-Carrasco MA, Peñas PF, Pajares JM, García-Díez A. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with psoriasis and lichen planus: Prevalence and effect of eradication therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1275–6. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.10.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campanati A, Ganzetti G, Martina E, Giannoni M, Gesuita R, Bendia E, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection in psoriasis: Results of a clinical study and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:e109–14. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Türkmen D, Özcan H, Kekilli E. Relation between psoriasis and Helicobacter pylori. Turk J Dermatol. 2011;5:39–42. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pietrzak A, Jastrzebska I, Chodorowska G, Maciejewski R, Dybiec E, Juszkiewicz-Borowiec M, et al. Psoriasis vulgaris and digestive system disorders: Is there a linkage? Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2009;47:517–24. doi: 10.2478/v10042-009-0107-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin Hübner A, Tenbaum SP. Complete remission of palmoplantar psoriasis through Helicobacter pylori eradication: A case report. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:339–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2007.02634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ali M, Whitehead M. Clearance of chronic psoriasis after eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:753–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kutlubay Z, Zara T, Engin B, Serdaroǧlu S, Tüzün Y, Yilmaz E, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and skin disorders. Hong Kong Med J. 2014;20:317–24. doi: 10.12809/hkmj134174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Testerman TL, Morris J. Beyond the stomach: An updated view of Helicobacter pylori pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:12781–808. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i36.12781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Versalovic J. Helicobacter pylori. Pathology and diagnostic strategies. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003;119:403–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magen E, Delgado JS. Helicobacter pylori and skin autoimmune diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:1510–6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i6.1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fry L, Baker BS. Triggering psoriasis: The role of infections and medications. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:606–15. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qayoom S, Ahmad QM. Psoriasis and Helicobacter pylori. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:133–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fabrizi G, Carbone A, Lippi ME, Anti M, Gasbarrini G. Lack of evidence of relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and psoriasis in childhood. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bilardi C, Biagini R, Dulbecco P, Iiritano E, Gambaro C, Mele MR, et al. Stool antigen assay (HpSA) is less reliable than urea breath test for post-treatment diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1733–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patel SK, Pratap CB, Jain AK, Gulati AK, Nath G. Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori : What should be the gold standard? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:12847–59. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i36.12847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]