Abstract

Protease enzymes generated from injured cells and leukocytes are the primary cause of myocardial cell damage following ischemia/reperfusion (I/R). The inhibition of protease enzyme activity via the administration of particular drugs may reduce injury and potentially save patients' lives. The aim of the current study was to investigate the cardioprotective effects of treatment with recombinant human secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (rhSLPI) on in vitro and ex vivo models of myocardial I/R injury. rhSLPI was applied to isolated adult rat ventricular myocytes (ARVMs) subjected to simulated I/R and to ex vivo murine hearts prior to I/R injury. Cellular injury, cell viability, reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, and levels of associated proteins were assessed. The results demonstrated that administration of rhSLPI prior to or during sI/R significantly reduced the death and injury of ARVMs and significantly reduced intracellular ROS levels in ARVMs during H2O2 stimulation. In addition, treatment of ARVMs with rhSLPI significantly attenuated p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activation and increased the activation of Akt. Furthermore, pretreatment of ex vivo murine hearts with rhSLPI prior to I/R significantly decreased infarct size, attenuated p38 MAPK activation and increased Akt phosphorylation. The results of the current study demonstrated that treatment with rhSLPI induced a cardioprotective effect and reduced ARVM injury and death, intracellular ROS levels and infarct size. rhSLPI also attenuated p38 MAPK phosphorylation and activated Akt phosphorylation. These results suggest that rhSLPI may be developed as a novel therapeutic strategy of treating ischemic heart disease.

Keywords: myocardial ischemia, protease inhibitor, ischemia-reperfusion injury, p38-mitogen-activated protein kinase, protein kinase B, cardioprotection

Introduction

Despite advances in knowledge and technology regarding health, myocardial ischemia remains the most common cause of mortality worldwide and the number of people succumbing to myocardial ischemia is predicted to increase over the coming decades (1,2). In the majority of cases, myocardial infarction is a consequence of coronary occlusion that results in an insufficient blood supply to the myocardium, leading to irreversible necrosis (3). Restoration of blood flow of the ischemic region, known as reperfusion, is the most effective therapeutic strategy of rescuing myocardial cells and saving patients' lives. However, as it results in the abrupt restoration of the oxygen supply, myocardial reperfusion itself may aggravate myocardial injury, leading to reperfusion injury (4). During myocardial ischemia and reperfusion, cardiac cell death, calcium overload and mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opening occur, resulting in the generation of reactive oxygen species (RO) (5–7). Various protease enzymes are secreted during ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury. These enzymes are generated from neighboring cells that are damaged following I/R injury, leading to increased cell death and the injury of normal cardiomyocytes surrounding the ischemic area (5–7). In addition, leukocytes and neutrophils infiltrate the ischemic area during reperfusion and secrete serine various protease enzymes, including cathepsin G, elastase and trypsin (8). Necrotic cells also secrete intracellular protease enzymes, which contribute to heart tissue damage and ultimately impair cardiac function (5–7). Therefore, inhibiting protease activity may be a method of preventing cardiac tissue injury following myocardial ischemia.

Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI) is an 11.7 kDa long cationic non-glycosylated protein that belongs to the Whey Acidic Protein (WAP) family (9–11). SLPI inhibits numerous leukocyte serine proteases, including trypsin and chymotrypsin in pancreatic acinar cells, elastase and cathepsin G in neutrophils, and chymase in mast cells (10–12). SLPI is a frontline protein that directly and indirectly defends against infection by viruses, bacteria and fungi (10). SLPI also acts as anti-inflammatory mediator, protecting host tissue from the excessive tissue damage induced by proteolytic enzymes secreted during inflammation (10). Therefore, SLPI may be a novel therapeutic strategy to treat myocardial ischemia.

Schneeberger et al (13) reported on the effects of rhSLPI in cardiac transplantation and demonstrated that supplementation of recombinant human (rh)SLPI in the cold-preservative solution used to preserve hearts prior to transplant improves the cardiac score of these hearts following transplantation. rhSLPI serves a crucial role in early myocardial performance and post-ischemic inflammation following cardiac transplantation (13). However, the immediate effects of rhSLPI on myocardial I/R injury at the cellular and molecular levels have not yet been investigated. Therefore, rhSLPI may be a developed as a cardioprotective agent to treat myocardial I/R.

Therefore, the aim of the current study was to investigate the effect of rhSLPI on isolated adult rat ventricular myocytes (ARVMs) subjected to simulated I/R and to investigate the cardioprotective effects of rhSLPI on an ex vivo ischemia/reperfusion isolated murine heart model.

Materials and methods

Reagents

All basic chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). M199 medium was obtained from Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. (Waltham, MA, USA). For SDS-PAGE and western blot analysis, 30% polyacrylamide solution was purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc. (Hercules, CA, USA) and the polyvinylidenedifluoride (PVDF) membrane was purchased from GE Healthcare Life Sciences (Little Chalfont, UK). The antibodies for the dual phosphorylated (p)-Thr180/Tyr182 form of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK; cat. no. sc-17852-R), total p38 MAPK (cat. no. sc-728), p-Akt (cat. no. sc-293125) and total Akt (cat. no. sc-8312) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Dallas, TX, USA). Enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) solution was purchased from GE Healthcare Life Sciences and collagenase type II was purchased from Worthington Biochemical Corporation (Lakewood, NJ, USA). rhSLPI was purchased from Sino Biological, Inc. (Beijing, China).

Experimental animals

Adult male Wistar rats (8 weeks old) weighing 200–250 g (n=6) and adult male C57BL/6 mice (8 weeks old) weighing 25–30 g (n=18) were obtained from the National Animal Center, Salaya Campus, Mahidol University (Bangkok, Thailand). All animals were maintained under environmentally controlled conditions (a temperature of 22±1°C, humidity of 45–60% and 12-h light/dark cycle) at the Center for Animal Research, Naresuan University (Phitsanulok, Thailand). All protocols used in the current study were approved by the animal ethics committee of the Center for Animal Research, Naresuan University (approval no. NU-AE550732).

Isolation of ARVMs and culture

The Wistar rats were euthanized by intraperitoneal injection (IP) with pentobarbital sodium (Nembutal® Sodium Solution CII; 100 mg/kg; Akorn, Inc., Lake Forest, IL, USA) and lithium heparin (150 U; Government Pharmaceutical Organization, Bangkok, Thailand). Adult rat ventricular myocytes (ARVMs) were isolated from the hearts using collagenase-based enzymatic digestion. Hearts were excised and initially perfused for 10 min with a modified Krebs solution (solution A) containing 130 mM NaCl, 4.5 mM KCl, 1.4 mM MgCl2, 0.4 mM NaH2PO4, 0.75 mM CaCl2, 4.2 mM HEPES, 20 mM taurine, 10 mM creatine and 10 mM glucose at pH 7.3 at 37°C. Hearts were then perfused with a calcium-free solution containing 100 µM EGTA for 5 min (solution B), followed by perfusion with solution A containing 100 µM CaCl2 and 0.4 mg/ml Type II collagenase for 30 min at 37°C. Following enzymatic perfusion, ventricles were cut into small pieces, which were incubated in 20 ml collagenase solution. Ventricles were incubated with 100% O2 for a further 7 min at 37°C and underwent regular gentle triturating. Isolated cardiomyocytes were separated from undigested ventricular tissue using a cell strainer. Subsequently, isolated myocytes were allowed to pellet at the bottom of the tube (sedimentation by gravity) and the supernatant was removed and replaced with solution A containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) and 500 µM CaCl2. Isolated cardiomyocytes were then allowed again to sediment at the bottom of the tube (sedimentation by gravity) and the supernatant was then removed and replaced with 10 ml solution A containing 1 mM CaCl2. The cell pellet was washed with M199 culture medium containing 100 IU/ml penicillin/streptomycin. Myocytes were resuspended in M199 supplemented with 2 mM creatine, 2 mM carnitine and 5 mM taurine, and then seeded on pre-laminin-coated 6-well plates (15 µg/ml laminin). Myocytes were allowed to adhere for 2 h in an incubator containing 5% CO2 at 37°C. The culture medium was replenished with fresh modified M199 medium, prior to further experiments.

Simulated ischemia (sI) protocol

sI was performed following a modified protocol (14). ARVMs were incubated with a specific basic buffer (137 mM NaCl, 3.8 mM KCl, 0.49 mM MgCl2, 0.9 mM CaCl2 and 4.0 mM HEPES), 20 mM 2-deoxyglucose, 20 mM sodium lactate and 1 mM sodium dithionite at pH 6.5, in order to induce sI. The control buffer was composed of the basic buffer (137 mM NaCl, 3.8 mM KCl, 0.49 mM MgCl2, 0.9 mM CaCl2 and 4.0 mM HEPES), supplemented with 20 mM D-glucose and 1 mM sodium pyruvate. ARVMs subjected to 20 min sI and 2 h reperfusion (sI/R) were treated with 0, 1, 10, 100, 1,000 and 10,000 ng/ml rhSLPI. The treatment was applied either 2 h prior to sI, during sI or at the onset of reperfusion. Following reperfusion, the culture medium was collected to assess lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity and cell viability was determined using the trypan blue dye exclusion assay. Another set of experiments was performed to determine the most effective concentration of rhSLPI. Cells were treated with 0, 200, 400, 600, 800 and 1,000 ng/ml rhSLPI prior to or during sI. Subsequently, cell viability was determined using the trypan blue dye exclusion assay and cell injury was assessed by determining released-LDH activity.

Determination of cell viability

The viability of ARVMs was assessed using the trypan blue dye exclusion method. Following reperfusion, the culture medium was removed and cells were incubated in 0.4% trypan blue solution for 1–2 min at room temperature. Following incubation, the numbers of trypan blue-positive and negative cells were counted under a light microscope in 5 different microscopic fields. The percentage of surviving cells from the total amount of cells was then calculated and the relative percentage of cell viability was compared with the control group.

Measurement of cellular injury

Released-Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) enzyme activity was measured by the LDH SCE mod. liquiUV kit (cat. no. 12214; HUMAN Diagnostics Worldwide, Wiesbaden, Germany). A total of 10 µl culture medium was mixed with 1,000 µl LDH activity assay buffer and incubated at 37°C for 5 min. Then, 250 µl substrate reagent was added. The solution was mixed and after 1 min, absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 340 nm. The mean absorbance change per minute (ΔA/min) was measured to evaluate released-LDH activity using the following formula: LDH activity (U/I)=ΔA/min × 20,000.

Measurement of intracellular ROS level production

ARVMs were cultured with modified M199 medium in 24-well black plates and maintained at 37°C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and 95% O2. The culture medium was removed and the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Subsequently, cells were incubated with M199 medium containing 25 µM carboxy-H2DCFDA (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) in a dark room for 30 min at 37°C. The medium containing carboxy-H2DCFDA was discarded and ARVMs were washed once with PBS. For rhSLPI treatment, 500 µl M199 medium containing various concentrations of rhSLPI (0, 200, 400, 600, 800 and 1,000 ng/ml) was added and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Subsequently, cells were incubated with 250 µM H2O2 for 30 min at 37°C. The control cells were incubated with M199 medium without treatment. ROS activity was determined by measuring fluorescence intensity using an EnSpire Multimode Plate Reader (PerkinElmer, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) at an excitation wavelength of 498 nm and emission wavelength of 522 nm.

Ex vivo perfusion of isolated mouse hearts and infarct size measurement

The ex vivo ischemia/reperfusion protocol was based on a previous study (15). A total of 18 adult male C57BL/6 mice (25–30 g; n=6 in each group) were divided into 3 different groups: An I/R group, an I/R + 400 ng/ml rhSLPI group and an I/R + 1,000 ng/ml rhSLPI group. Mice were euthanized with IP injection of pentobarbital (100 mg/kg) and heparin (150 U). Hearts were rapidly isolated and placed in ice-cold modified Krebs-Henseleit buffer (KHB) consisting of 118.5 mM NaCl, 25.0 mM NaHCO3, 4.75 mM KCl, 1.18 mmol KH2PO4, 1.19 mM MgSO4, 11.0 mM D-glucose and 1.4 mM CaCl2. The excised heart was cannulated via the aorta and retrograde perfusion on a Langendorff system was performed at a constant pressure of 80 mmHg with KHB equilibrated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 at 37°C. Hearts were perfused with KHB for 10 min and were then perfused with KHB solution containing 400 ng/ml or 1,000 ng/ml rhSLPI for 30 min. Hearts from mice in the I/R group underwent perfusion with KHB alone. Hearts were then subjected to ischemia by attenuating perfusion for 30 min (no-flow). Reperfusion was performed with KHB for a further 2 h. At the end of the protocol, hearts were perfused with 5 ml 1% triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) in PBS for 1 min at 37°C and incubated in 1% TTC at 37°C for 10 min. Atria were removed and hearts were blotted dry, weighed and stored at −20°C for 1 week. Prior to heart tissue sectioning, the hearts were thawed, placed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 1 min at room temperature and embedded in 5% agarose. Agarose heart blocks were sectioned from apex to base in 0.75-mm slices using a vibratome (Agar Scientific Ltd., Essex, UK). Following sectioning, slices were fixed in 10% formaldehyde overnight at room temperature prior to incubation with PBS for 1 day at 4°C. Sections were then compressed between glass plates (0.75-mm apart) and scanned by a Gel Doc™ XR+ System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). All analyses of infarct size were performed by two investigators that were blinded with regards to the group assignments.

Measurement of p38 MAPK and Akt activation by western blotting

ARVMs were washed twice in ice-cold PBS prior to the addition of 200 µl 2× SDS-sample buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol. Cells were scraped and samples were transferred to pre-cooled micro-centrifuge tubes. For protein extraction, hearts from the I/R, I/R + 400 ng/ml rhSLPI group and I/R + 1,000 ng/ml rhSLPI groups (each, n=3) were perfused on a Langendorff perfusion system, subjected to 30 min stabilization, perfused with KHB containing 400 ng/ml and 1,000 ng/ml rhSLPI or KHB alone as a vehicle for 30 min prior to 10 min without perfusion (global ischemia). At the end of the global ischemia, hearts were rapidly snap frozen. Approximately 50 mg of heart samples were weighed and homogenized in 500 µl homogenization buffer (20 mM Tris pH 6.8, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 5 mM sodium fluoride, and 1 cOmplete™, Mini Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablet; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA). Heart homogenates were centrifuged at 13,148 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatants were collected and an equal volume of 2X SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing 10% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol and bromophenol blue dye was added. Samples were boiled for 10 min and stored at −80°C prior to analysis. Extracted proteins (30 µg/lane) were separated on 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels (prepared from a 30% polyacrylamide solution) and transferred to PVDF membranes that were blocked for 1 h with 5% non-fat milk and 1% BSA in Tris-buffered saline (pH 7.4) containing 0.1% Triton X-100. Membranes were then probed overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against total p38, diphospho-p38, total Akt and p-Akt (all 1:1,000). Following washing and exposure for 1 h at room temperature to horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, antibody-antigen complexes were visualized using ECL, revealed as bands corresponding to the detected proteins of interest. Band densities were detected by Gel DocXR+ Imaging System, quantified using Image Lab™ software (version 6.0; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) and compared, providing information on the relative abundance of the protein of interest.

Statistical analysis

All values are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. All comparisons were assessed for significance using one-way analysis of variance, followed by the Tukey-Kramer test. Statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism version 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

rhSLPI-treatment prior to or during sI/R attenuates cell death following sI/R injury

The results demonstrated that rhSLPI-treatment administered 2 h prior to sI or during sI significantly reduced sI/R-induced cell death. Pretreatment of ARVMs with 1, 10, 100 and 1,000 ng/ml rhSLPI significantly increased cell viability compared with the untreated sI/R group (P<0.05; Fig. 1A). Furthermore, pre-treatment with 100 and 1,000 ng/ml rhSLPI significantly decreased LDH activity compared with the untreated sI/R group (P<0.05; Fig. 1B). In addition, treatment of ARVMs with rhSLPI during sI also significantly decreased the cell death induced by sI/R. Treatment with 100 ng/ml and 1,000 ng/ml rhSLPI significantly increased cell viability compared with the untreated sI/R group (P<0.05; Fig. 1C). Furthermore, 1,000 ng/ml rhSLPI significantly decreased LDH activity in the supernatant (P<0.05; Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

Optimization of the cardioprotective dose of rhSLPI for ARVMs subjected to sI/R. ARVMs were cultured with various concentrations of rhSLPI and treated over three different periods, including (A and B) 2 h prior to sI, (C and D) at the onset of sI and (E and F) at the onset of reperfusion. Following rhSLPI treatment, all groups were subjected to 20 min sI followed by 2 h reperfusion. The percentage of viable cells and released LDH activity in all groups were determined. The results are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n=3). *P<0.05 vs. control group; #P<0.05 vs. sI group. rhSLPI, recombinant human secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor; sI, stimulated ischemia; ARVM, adult rat ventricular myocytes; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; sI/R, stimulated ischemia/reperfusion.

By contrast, rhSLPI-treatment at the onset of reperfusion (Fig. 1E) did not increase the viability of cardiac cells following sI/R. Similarly, LDH activity was not significantly reduced when cells were treated with rhSLPI at the onset of reperfusion (Fig. 1F). This was the case with all doses of rhSLPI. The results of these indicated that the rhSLPI minimum concentration that provided maximal cardioprotection in ARVMs was 100 ng/ml in case of pretreatment and 1,000 ng/ml for treatment during sI.

Identification of the maximum rhSLPI concentration required to provide cardioprotection in ARVMs subjected to sI/R

To identify the maximum rhSLPI concentration required to induce cardioprotection in ARVMs without inducing any toxicity, ARVMs were treated with 0, 200, 400, 600, 800 and 1,000 ng/ml rhSLPI 2 h prior to sI or immediately following the onset of sI. Following treatment, all groups were subjected to sI for 20 min followed by 2 h reperfusion. Cell viability and cell injury were determined.

The results indicated that following 2 h reperfusion, the percentage of viable cells in the groups treated with rhSLPI either 2 h prior to sI or at the onset of sI increased compared with the sI group. Pretreatment of ARVMs with 200, 400, 600, 800 and 1,000 ng/ml rhSLPI significantly increased the viability of ARVMs exposed to sI/R injury compared with the sI group (P<0.05; Fig. 2A). Furthermore, these concentrations significantly decreased LDH activity in the supernatants compared with the sI group (P<0.05; Fig. 2B). In addition, treatment of ARVMs with 400, 800 and 1,000 ng/ml at the onset of sI significantly increased the viability of ARVMs compared with the sI group (P<0.05; Fig. 2C) and these concentrations significantly decreased LDH activity compared with the sI group (P<0.05; Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Determination of the maximum rhSLPI concentration required to provide cardioprotection in ARVMs subjected to sI/R. The percentage of (A) viable cells and (B) LDH activity following pretreatment of ARVMs with various concentrations of rhSLPI. The percentage of (C) viable cells and (D) LDH activity following treatment of ARVMs with various concentrations of rhSLPI during sI. The percentage of (E) viable cells and (F) LDH activity following treatment of ARVMs with various concentrations of rhSLPI without sI. The results are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n=3). *P<0.05 vs. control group; #P<0.05 vs. sI group. rhSLPI, recombinant human secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor; ARVM, adult rat ventricular myocytes; sI, stimulated ischemia; sI/R, stimulated ischemia/reperfusion; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

The toxicity of rhSLPI was determined by culturing ARVMs with 0, 200, 400, 600, 800 and 1,000 ng/ml rhSLPI for 24 h and then measuring cell viability and cell injury. The results indicated that treatment with all concentrations of rhSLPI did not reduce cell viability (Fig. 2E) and did not increase LDH activity (Fig. 2F). This demonstrates that rhSLPI does not induce toxicity in ARVMs.

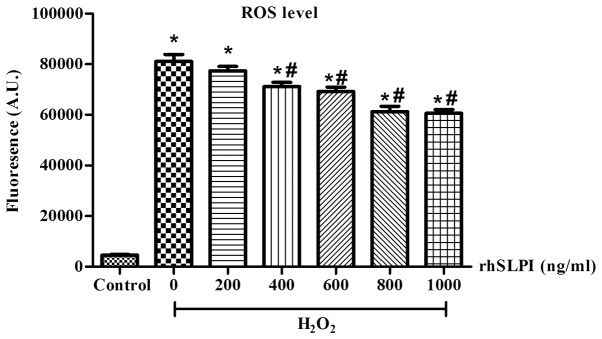

Treatment of ARVMs by rhSLPI decreases ROS levels

To further investigate the cardio-protective effects of rhSLPI treatment during sI/R injury, intracellular ROS generation was measured following H2O2 challenge.

The results demonstrated that exposure to H2O2 significantly increased intracellular ROS levels compared with the control group (P<0.05; Fig. 3). However, treatment of ARVMs with 400, 600, 800 and 1,000 ng/ml rhSLPI significantly reduced intracellular ROS levels compared with untreated ARVMs (P<0.05). Notably, 400 ng/ml rhSLPI was the lowest concentration of rhSLPI that significantly reduced ROS production.

Figure 3.

Cellular ROS levels following treatment of ARVMs with rhSLPI. ARVMs were incubated with carboxy-H2DCFDA and treated with 0, 200, 400, 600, 800 and 1,000 ng/ml rhSLPI. Following incubation, H2O2 was applied to each group and ROS production was determined using the EnSpire Multimode Plate Reader. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n=3). *P<0.05 vs. control group; #P<0.05 vs. H2O2 treated group. ROS, reactive oxygen species; ARVM, adult rat ventricular myocytes; rhSLPI, recombinant human secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor; A.U., arbitrary unit.

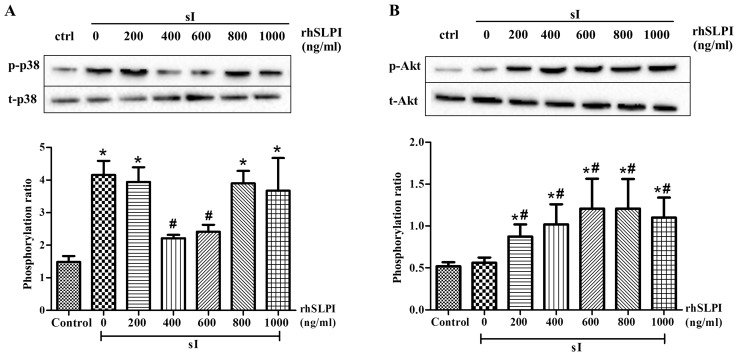

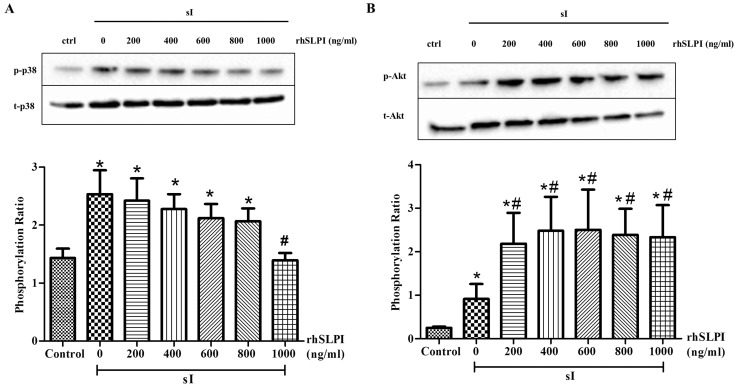

Treatment of ARVMs by rhSLPI attenuates p38 MAPK phosphorylation and increases Akt activation following sI

To determine the cellular signaling in response to rhSLPI treatment in ARVMs during sI/R injury, western blot analysis was performed to determine the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and Akt.

The results demonstrated that the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK was significantly increased following sI (P<0.05; Fig. 4A). However, pretreatment with 400 and 600 ng/ml rhSLPI significantly reduced p38 MAPK phosphorylation (P<0.05). In addition, the results demonstrated that treatment with 200–1,000 ng/ml rhSLPI prior to sI significantly increased Akt phosphorylation compared with the sI group (P<0.05; Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Cellular signaling in response to pretreatment of ARVMs with rhSLPI, subjected to ischemia/reperfusion. ARVMs were treated with 200, 400, 600, 800 and 1,000 ng/ml rhSLPI for 2 h prior to sI. The phosphorylation of (A) p38 MAPK and (B) Akt was determined by western blot analysis. Each bar graph represents the phosphorylation ratio (p-/t-) of p38 MAPK and Akt. *P<0.05 vs. control group; #P<0.05 vs. sI group. ARVM, adult rat ventricular myocytes; rhSLPI, recombinant human secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor; sI, stimulated ischemia; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; p-phosphorylated; t-, total.

In addition, treatment of ARVMs with rhSLPI at the onset of sI reduced the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5A). Treatment of ARVMs with 1,000 ng/ml rhSLPI at the onset of sI significantly reduced p38 MAPK activation compared with the sI group (P<0.05). The results also indicated that treatment of ARVMs with 200–1,000 ng/ml rhSLPI at the onset of sI significantly increased the phosphorylation of Akt compared with the sI group (P<0.05; Fig. 5B). This indicates that treatment of ARVMs with rhSLPI increases Akt phosphorylation and attenuates the activation of p38 MAPK.

Figure 5.

Cellular signaling following treatment of ARVMs with rhSLPI during sI. ARVMs were treated with 200, 400, 600, 800 and 1,000 ng/ml rhSLPI at the onset of sI. The activation of (A) p38 MAPK and (B) Akt was determined by western blot analysis. Each bar graph represents the phosphorylation ratio (p-/t-) of p38 MAPK and Akt. *P<0.05 vs. control group; #P<0.05 vs. sI group. ARVM, adult rat ventricular myocytes; rhSLPI, recombinant human secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor; sI, stimulated ischemia; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; p-, phosphorylated; t-, total.

Evaluation of the cardioprotective effects of rhSLPI in an ex vivo murine model of myocardial I/R

Hearts isolated from adult male C57BL/6 mice were perfused on a Langendorff system with buffered solutions containing 400 or 1,000 ng/ml rhSLPI during I/R injury (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

The effect of rhSLPI treatment on the myocardial infarct size of ex vivo murine hearts during myocardial I/R. (A) The study protocol for all experimental groups. The hearts of adult male C57BL/6 mice were perfused for 40 min with modified Krebs solution, or with modified Krebs solution containing 400 ng/ml rhSLPI or 1,000 ng/ml rhSLPI. Hearts were then subjected to 30 min global ischemia and 2 h reperfusion. (B) Infarct size was determined by TTC staining. Each bar graph represents the mean ± standard error of the mean (n=6). *P<0.05 vs. I/R alone. rhSLPI, recombinant human secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor; I/R, ischemia/reperfusion; LV, left ventricle.

The results indicate that following 30 min global ischemia and 2 h reperfusion, the infarct size was 48.40±4.23% (Fig. 6B). However, pretreatment with either 400 or 1,000 ng/ml rhSLPI significantly reduced the infarct size compared with the control (P<0.05; Fig. 6B).

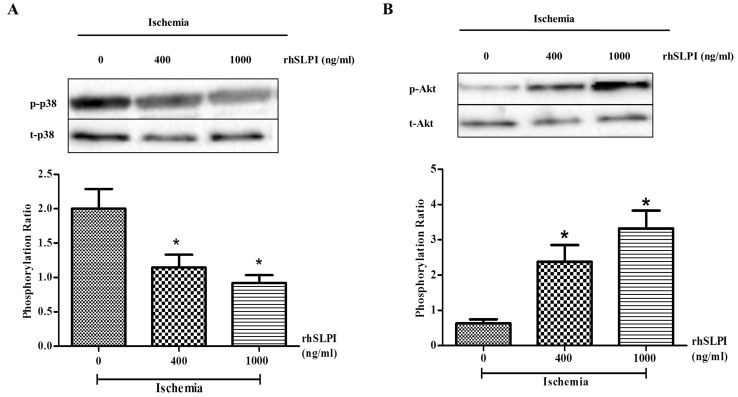

Pretreatment with rhSLPI attenuates p38 MAPK activation and increases Akt activation in ex vivo I/R hearts

To further investigate the cardioprotective effects of rhSLPI pretreatment on ex vivo mouse hearts, cellular signaling in response to rhSLPI treatment following I/R injury was investigated. Hearts were perfused with 400 or 1,000 ng/ml rhSLPI for 30 min prior to global ischemia and 10 min no-flow. p38 MAPK and Akt phosphorylation ratios were determined by western blotting. The results demonstrated that, following 10 min global ischemia, p38 MAPK was highly phosphorylated in the I/R control group (Fig. 7A). However, pre-treatment with 400 or 1,000 ng/ml rhSLPI significantly decreased p38 MAPK activation in a dose-dependent manner (P<0.05; Fig. 7A). By contrast, pretreatment with 400 or 1,000 ng/ml rhSLPI significantly increased Akt phosphorylation compared with the I/R non-treated control group (P<0.05; Fig. 7B). These results indicate that pretreatment with rhSLPI increases Akt phosphorylation and attenuates p38 MAPK activation in an ex vivo I/R murine model.

Figure 7.

Signaling in response to treatment of ex vivo murine hearts with rhSLPI during myocardial I/R. The hearts of adult male C57BL/6 mice were perfused for 40 min with modified Krebs solution or modified Krebs solution containing 400 ng/ml or 1,000 ng/ml rhSLPI followed by 10 min global ischemia. Hearts were homogenized with homogenizing buffer and protein was collected. The activation of (A) p38 MAPK and (B) Akt was assessed using western blot analysis. Each bar graph represents the fold phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and Akt. *P<0.05 vs. I/R control group (n=3). rhSLPI, recombinant human secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; p-, phosphorylated; t-, total; I/R, ischemia/reperfusion.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that rhSLPI exhibits a protective effects on in vitro and ex vivo sI/R murine models and determined the mechanism by which treatment with rhSLPI inhibits the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and activates the Akt cell survival pathway in ARVMs and the ex vivo heart. The results of the current study indicated that in the case of ARVMs that underwent sI/R injury, the administration of exogenous rhSLPI, prior to or at the onset of sI significantly reduced cardiac cell death and cell injury.

During myocardial I/R injury, levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), interleukin (IL) 6, IL-8, and mitochondrial pyruvate carrier-1 (MPC1), are upregulated and secreted from adjacent cardiomyocytes, resulting in leukocyte infiltration (5–7). Infiltrated leukocytes, particularly neutrophil, secrete numerous serine protease enzymes, including cathepsin G, elastase and trypsin, which contribute to heart tissue damage, myocardial necrosis and functional impairment (5,7). Therefore, inhibiting protease activity, as well as attenuating inflammatory responses, may be a promising therapeutic strategy to prevent and treat cardiac tissue injury.

Previous studies have determined the effects of protease inhibitors on ischemic injury. In a rabbit model of heterotopic cardiac transplantation, the serine elastase inhibitor elafin decreased post-cardiac transplant coronary arteriopathy and decreased myocardial necrosis following transplantation (16). Treatment with two specific elastase inhibitors, elafin and ICI 200880, in in situ-perfused rat heart models of repetitive ischemia and myocardial infarction improved regional myocardial function and reduced infarct size (17). Furthermore, inhibition of the serine protease enzymes secreted by neutrophils exhibited cardioprotective effects against myocardial I/R injury (18,19). Treatment with PR-39, a potent neutrophil inhibitor, in a murine model of myocardial I/R injury significantly inhibited the recruitment of leukocytes into inflamed tissue, thus decreasing infarct size (18). In a canine model of heart transplantation, treatment with the neutrophil elastase inhibitor ONO-5046 Na reduced I/R injury and inhibited neutrophil elastase and inflammatory cytokine release (19). However, SLPI may be the broadest and most promising method of treating myocardial I/R injury compared with other protease inhibitors because SLPI can inhibit various protease enzyme and exhibits anti-oxidant functions (20). SLPI attenuated cell injury in a murine hepatic I/R model by inhibiting neutrophil accumulation (21). Furthermore, SLPI decreased serum levels of TNF-α, the CXC chemokine macrophage inflammatory protein, and suppressed activation of the transcription factor nuclear factor (NF)-κB in the liver (21). Exogenous rhSLPI added to cold-preservative buffer improved the cardiac score of hearts (a system that grades myocardial contraction) following transplantation and reduced the expression of protease enzymes and pro-inflammatory cytokines in mice undergoing heart transplants (13).

Studies have investigated the effects of SLPI on inflammation. SLPI is a protein involved in downregulating macrophage responses against bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS) by inhibiting NF-κB activation (22). Ding et al (23) demonstrated that the anti-inflammatory effects of SLPI on macrophages may be due to the inhibition of cluster of differentiation (CD)14 on the macrophage membrane or by inhibiting the formation of LPS-soluble CD14 complexes. It has been demonstrated that exogenous SLPI is internalized into monocytes and is distributed throughout the nucleus and cytoplasm. It then inhibits NF-κB activation by blocking the degradation of the inhibitor of NF-κB (24). Interestingly, Taggart et al (24) demonstrated that SLPI competes with the NF-κB subunit p65 to bind to the promoter of NF-κB, resulting in the decreased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Furthermore, the spraying of SLPI aerosols suppresses respiratory epithelial neutrophil elastase (NE) levels and attenuates the inflammation of the cystic fibrosis epithelial surface by reducing IL-8 levels (25). Adapala et al (26) reported that SLPI expression in the adipose tissue is upregulated in obesity and that the pretreatment of adipocytes with exogenous SLPI results in the downregulation of LPS-induced IL-6 gene expression and protein secretion in adipocytes. In addition, exogenous SLPI increased the proliferation and differentiation of adult neural stem cells via the upregulation of cyclin D1 and suppression of the cell differentiation regulator HES1 (27). The treatment of monocytes with exogenous SLPI inhibited the TNF-α-induced caspase-3 activation and the DNA degradation associated with apoptosis in monocytes (28). The results of other studies investigating different types of cells suggest that treatment with rhSLPI induces similar anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects (29–31).

The excessive formation of ROS during I/R injury induces cardiac cell death directly by inducing cell membrane and protein damage (32,33) or indirectly by activating pro-apoptotic pathways, as well as recruiting inflammatory cells (32,34–38). It has been suggested that SLPI reduces cellular ROS generation. The administration of rhSLPI suppressed NE and glutathione levels in the respiratory epithelial lining fluid of the lung and caused a concomitant increase in anti-H2O2 capacity (39). Furthermore, the overexpression of rhSLPI and glutathione peroxidase-3 reduced oxidant-induced lung injury and inflammation (40). This indicates that administration of rhSLPI may be used to treat diseases similar to myocardial I/R injury that are characterized by an excess of serine proteases and oxidative stress. The results of the current study demonstrate that treatment with ARVMs by rhSLPI decrease cellular ROS generation during H2O2 challenge. To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first to demonstrate that the treatment of ARVMs with rhSLPI reduces cellular ROS generation and may therefore be an effective method of treating ARVMs in sI/R. However, the reduction of ROS production and cardiac cell death in ARVMs following treatment with rhSLPI may be due to increases in glutathione levels in cardiac cells rather than a direct effect on ROS scavenging. Therefore, further research investigating the mechanisms by which rhSLPI reduces intracellular ROS levels in I/R is warranted.

Myocardial I/R injury is mediated by numerous signaling pathways, including p38 MAPK. Myocardial I/R injury activates p38 MAPK, which induces cardiac cell death (15,41–45). The pre-clinical investigation indicated that the reduction of p38 MAPK activation reduces myocardial injury (44). Given that the treatment of ARVMs with rhSLPI reduces cell death following I/R injury, it was hypothesized that the decrease in cardiac cell death following treatment of ARVMs with rhSLPI is caused by the attenuation of p38 MAPK activation. The results of the current study indicated that the administration of exogenous rhSLPI prior to or at the onset of sI significantly attenuated the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK. These results indicate that rhSLPI administration prior to or at the onset of ischemic insult may attenuate the activation of p38 MAPK and may therefore be an effective method of protecting cardiac cells against I/R.

Akt is a serine/threonine protein kinase and serves an important role in cell survival (46–49). The activation of Akt signaling protects cardiac cells from apoptosis, resulting in the attenuation of myocardial I/R injury (46–49). It was therefore hypothesized that the treatment of ARVMs with rhSLPI may stimulate Akt phosphorylation during sI/R injury. The results demonstrated that treatment of ARVMs with rhSLPI prior to or during sI significantly activated Akt phosphorylation. This suggests that the administration of rhSLPI not only protects the cell by inhibiting the activation of p38 MAPK but also increases cell survival by activating the Akt pathway.

Although it has been demonstrated that various treatments/interventions administered during reperfusion are effective at reducing infarct size, the results of the current study indicated that administering rhSLPI at the onset of reperfusion failed to protect ARVMs from sI/R induced cell death and cell injury. These results were similar to those of previous studies investigating the effects of treatments or interventions administered prior to ischemia, which may protect the heart from I/R injury (13,15). Indeed pre-treatment with the p38 MAPK inhibitors SB203580 and BIRB796 for 30 min prior to ischemia may significantly reduce infarct size (15). The results of a previous study conducted in an ischemic rat heart model indicated that SB203580 administered either prior to or during ischemia decreased the incidence of ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation in the ischemic heart, decreased the phosphorylation of heat shock protein 27 and increased the phosphorylation of connexin 43 (50) However, treatment with SB203580 at the onset of reperfusion failed to protect the heart from ischemic insult (50). This may be due to the fact that, when administered at reperfusion, SB203580 does not inhibit the activation of p38 MAPK and the pro-apoptotic protein Bax, and does not protect the cardiac mitochondrial membrane potential (45). In addition, previous studies demonstrated that pretreatment with various types of compounds (including amifostine, barbaloin, simvastatin, lysophosphatidic acid and icariin) may also exhibit cardioprotective effects against I/R injury (51–55), similar to the results of the current study. Therefore, the results of the current study suggest that treatment with rhSLPI (400–1,000 ng/ml) prior to or at the onset of ischemia is most effective at protecting cardiac cells and reducing cardiac cell injury following I/R. Pre-treatment with 1,000 ng/ml rhSLPI in ex vivo murine hearts significantly reduced the infarct size. These results indicate that timing SLPI treatment with respect to the onset of ischemia is an important determinant of its therapeutic efficacy.

There were a number of limitations of the current study. Treatment of ARVMs by rhSLPI or treatment of ex vivo hearts with rhSLPI may not be representative of real-world physiological settings. The ex vivo model is useful in determining the actual effect of drugs or substance testing, as the heart undergoes direct perfusion with the test substance and the effect serum proteins binding to the test substance is avoided. In addition, the global ischemia protocol used in the current study is well-suited to study the effects of ischemia and hypoxia and determine the release of cellular constituents from coronary effluent, including enzymes and proteins, as well as markers of cardiac metabolism (56). The protocols used in the current study, including perfusion setting, fixation of the heart tissue by glutaraldehyde or formalin and determination of the infarct size are standard methods that have been used in previous studies (14,15,50,57,58). As aforementioned, an ex vivo model may not be representative of real clinical settings; therefore other relevant models, including treatment of intact hearts in an in vivo model of I/R may produce more relevant functional data that are closely associated with real physiological events in the heart, allowing a more reliable interpretation of the results. In addition, the number of animals used in each experiment in the current study was small; therefore a larger sample size should be used in future in vivo or clinical studies.

In conclusion, the results of the current study indicate that treatment with rhSLPI exhibits cardioprotective effects against myocardial I/R injury in in vitro and ex vivo models by reducing intracellular ROS levels and infarct size, attenuating p38 MAPK phosphorylation and activating Akt phosphorylation. The results suggest that rhSLPI may be developed as a potential therapeutic strategy to treat patients with ischemic heart disease.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the support from the Franco-Thai Scholarship program in 2015 and-2016 for authors SK and SBL. The authors would also like to thank the Newton Fund in cooperation with The Royal Golden Jubilee PhD Program for providing a PhD placement scholarship for EP, SK and MM. The authors are grateful to the Center for Animal Research, Naresuan University for their excellent technical assistance.

Funding

The present study was supported by The Royal Golden Jubilee PhD Program (grant no. PHD/0043/2555) - joint funding between the Thailand Research Fund, Naresuan University and National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT)-Naresuan University (grant no. R2558B06).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was approved by the animal ethics committee of the Center for Animal Research, Naresuan University (approval no. NU AE550732).

Authors' contributions

EP and SK conceived and designed the experiments. EP, JS, SBL, JN, HN, MM and SK performed the experiments and analyzed the data. EP, MM and SK wrote, re-checked, and proofread the paper.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.World Health Organization: World Health Statistics 2008. Geneva: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Writing Group Members, corp-author. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das SR, de Ferranti S, Després JP, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 update: A report from the american heart association. Circulation. 2016;133:e38–e360. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jennings RB, Reimer KA. The cell biology of acute myocardial ischemia. Annu Rev Med. 1991;42:225–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.42.020191.001301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yellon DM, Hausenloy DJ. Myocardial reperfusion injury. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1121–1135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Epelman S, Liu PP, Mann DL. Role of innate and adaptive immune mechanisms in cardiac injury and repair. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:117–129. doi: 10.1038/nri3800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boudoulas KD, Hatzopoulos AK. Cardiac repair and regeneration: The Rubik's cube of cell therapy for heart disease. Dis Model Mech. 2009;2:344–358. doi: 10.1242/dmm.000240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jordan JE, Zhao ZQ, Vinten-Johansen J. The role of neutrophils in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Re. 1999;43:860–878. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(99)00187-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuckleburg CJ, Newman PJ. Neutrophil proteinase 3 acts on protease-activated receptor-2 to enhance vascular endothelial cell barrier function. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:275–284. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouchard D, Morisset D, Bourbonnais Y, Tremblay GM. Proteins with whey-acidic-protein motifs and cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:167–174. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70579-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Majchrzak-Gorecka M, Majewski P, Grygier B, Murzyn K, Cichy J. Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI), a multifunctional protein in the host defense response. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2016;28:79–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moreau T, Baranger K, Dadé S, Dallet-Choisy S, Guyot N, Zani ML. Multifaceted roles of human elafin and secretory leukocyte proteinase inhibitor (SLPI), two serine protease inhibitors of the chelonianin family. Biochimie. 2008;90:284–295. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doumas S, Kolokotronis A, Stefanopoulos P. Anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial roles of secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor. Infect Immun. 2005;73:1271–1274. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1271-1274.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneeberger S, Hautz T, Wahl SM, Brandacher G, Sucher R, Steinmassl O, Steinmassl P, Wright CD, Obrist P, Werner ER, et al. The effect of secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI) on ischemia/reperfusion injury in cardiac transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:773–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacquet S, Nishino Y, Kumphune S, Sicard P, Clark JE, Kobayashi KS, Flavell RA, Eickhoff J, cotton M, Marber MS. The role of RIP2 in p38 MAPK activation in the stressed heart. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:11964–11971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707750200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumphune S, Bassi R, Jacquet S, Sicard P, Clark JE, Verma S, Avkiran M, O'Keefe SJ, Marber MS. A chemical genetic approach reveals that p38alpha MAPK activation by diphosphorylation aggravates myocardial infarction and is prevented by the direct binding of SB203580. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:2968–2975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.079228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cowan B, Baron O, Crack J, Coulber C, Wilson GJ, Rabinovitch M. Elafin, a serine elastase inhibitor, attenuates post-cardiac transplant coronary arteriopathy and reduces myocardial necrosis in rabbits afer heterotopic cardiac transplantation. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2452–2468. doi: 10.1172/JCI118692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tiefenbacher CP, Ebert M, Niroomand F, Batkai S, Tillmanns H, Zimmermann R, Kübler W. Inhibition of elastase improves myocardial function after repetitive ischaemia and myocardial infarction in the rat heart. Pflugers Arch. 1997;433:563–570. doi: 10.1007/s004240050315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffmeyer MR, Scalia R, Ross CR, Jones SP, Lefer DJ. PR-39, a potent neutrophil inhibitor, attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H2824–H2828. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.6.H2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ueno M, Moriyama Y, Toda R, Yotsumoto G, Yamamoto H, Fukumoto Y, Sakasegawa K, Nakamura K, Sakata R. Effect of a neutrophil elastase inhibitor (ONO-5046 Na) on ischemia/reperfusion injury using the left-sided heterotopic canine heart transplantation model. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2001;20:889–896. doi: 10.1016/S1053-2498(01)00281-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schneeberger S, Brandacher G, Mark W, Amberger A, Margreiter R. Protease inhibitors as a potential target in modulation of postischemic inflammation. Drug News Perspect. 2002;15:568–574. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2002.15.9.840061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lentsch AB, Yoshidome H, Warner RL, Ward PA, Edwards MJ. Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor in mice regulates local and remote organ inflammatory injury induced by hepatic ischemia/reperfusion. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:953–961. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(99)70355-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKiernan PJ, McElvaney NG, Greene CM. SLPI and inflammatory lung disease in females. Biochem Soc Trans. 2011;39:1421–1426. doi: 10.1042/BST0391421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ding A, Thieblemont N, Zhu J, Jin F, Zhang J, Wright S. Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor interferes with uptake of lipopolysaccharide by macrophages. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4485–4489. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4485-4489.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taggart CC, Cryan SA, Weldon S, Gibbons A, Greene CM, Kelly E, Low TB, O'neill SJ, McElvaney NG. Secretory leucoprotease inhibitor binds to NF-kappaB binding sites in monocytes and inhibits p65 binding. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1659–1668. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McElvaney NG, Nakamura H, Birrer P, Hébert CA, Wong WL, Alphonso M, Baker JB, Catalano MA, Crystal RG. Modulation of airway inflammation in cystic fibrosis. In vivo suppression of interleukin-8 levels on the respiratory epithelial surface by aerosolization of recombinant secretory leukoprotease inhibitor. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:1296–1301. doi: 10.1172/JCI115994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adapala VJ, Buhman KK, Ajuwon KM. Novel anti-inflammatory role of SLPI in adipose tissue and its regulation by high fat diet. J Inflamm (Lond) 2011;8:5. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-8-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mueller AM, Pedré X, Stempfl T, Kleiter I, Couillard-Despres S, Aigner L, Giegerich G, Steinbrecher A. Novel role for SLPI in MOG-induced EAE revealed by spinal cord expression analysis. J Neuroinflammation. 2008;5:20. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGarry N, Greene CM, McElvaney NG, Weldon S, Taggart CC. The ability of secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor to inhibit apoptosis in monocytes is independent of its antiprotease activity. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:507315. doi: 10.1155/2015/507315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Subramaniyam D, Hollander C, Westin U, Erjefält J, Stevens T, Janciauskiene S. Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor inhibits neutrophil apoptosis. Respirology. 2011;16:300–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2010.01901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seto T, Takai T, Ebihara N, Matsuoka H, Wang XL, Ishii A, Ogawa H, Murakami A, Okumura K. SLPI prevents cytokine release in mite protease-exposed conjunctival epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;379:681–685. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee SY, Nho TH, Choi BD, Jeong SJ, Lim DS, Jeong MJ. Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor reduces inflammation and alveolar bone resorption in LPS-induced periodontitis in rats and in MC3T3-E1 preosteoblasts. Animal Cells Systems. 2016;20:344–352. doi: 10.1080/19768354.2016.1250817. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoffman JW, Jr, Gilbert TB, Poston RS, Silldorff EP. Myocardial reperfusion injury: Etiology, mechanisms, and therapies. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2004;36:391–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raedschelders K, Ansley DM, Chen DD. The cellular and molecular origin of reactive oxygen species generation during myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;133:230–255. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gottlieb RA. Cell death pathways in acute ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2011;16:233–238. doi: 10.1177/1074248411409581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lucchesi BR. Myocardial ischemia, reperfusion and free radical injury. Am J Cardiol. 1990;65:14I–23I. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90120-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Venardos KM, Perkins A, Headrick J, Kaye DM. Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury, antioxidant enzyme systems, and selenium: A review. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:1539–1549. doi: 10.2174/092986707780831078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hausenloy DJ, Yellon DM. Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: A neglected therapeutic target. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:92–100. doi: 10.1172/JCI62874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferrari R, Agnoletti L, Comini L, Gaia G, Bachetti T, Cargnoni A, Ceconi C, Curello S, Visioli O. Oxidative stress during myocardial ischaemia and heart failure. Eur Heart J. 1998;19(Suppl B):B2–B11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gillissen A, Birrer P, McElvaney NG. Recombinant secretory leukoprotease inhibitor augments glutathione levels in lung epithelial lining fluid. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1993;75:825–832. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.2.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Masterson CH, O'Toole DP, Laffey JP. American Thoracic Society 2012 International Conference. San Francisco, California: 2012. Over expression of secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI) and glutathione peroxidase-3 (GPX3) attenuate inflammation and oxidant-mediated pulmonary epithelial injury. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaiser RA, Lyons JM, Duffy JY, Wagner CJ, McLean KM, O'Neill TP, Pearl JM, Molkentin JD. Inhibition of p38 reduces myocardial infarction injury in the mouse but not pig after ischemia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H2747–H2751. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01280.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gorog DA, Tanno M, Cao X, Bellahcene M, Bassi R, Kabir AM, Dighe K, Quinlan RA, Marber MS. Inhibition of p38 MAPK activity fails to attenuate contractile dysfunction in a mouse model of low-flow ischemia. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;61:123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ma XL, Kumar S, Gao F, Louden CS, Lopez BL, Christopher TA, Wang C, Lee JC, Feuerstein GZ, Yue TL. Inhibition of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase decreases cardiomyocyte apoptosis and improves cardiac function after myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. Circulation. 1999;99:1685–1691. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.99.13.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumphune S, Chattipakorn S, Chattipakorn N. Role of p38 inhibition in cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68:513–524. doi: 10.1007/s00228-011-1193-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumphune S, Surinkaew S, Chattipakorn SC, Chattipakorn N. Inhibition of p38 MAPK activation protects cardiac mitochondria from ischemia/reperfusion injury. Pharm Biol. 2015;53:1831–1841. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2015.1014569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu L, Li F, Zhao G, Yang Y, Jin Z, Zhai M, Yu W, Zhao L, Chen W, Duan W, Yu S. Protective effect of berberine against myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury: Role of Notch1/Hes1-PTEN/Akt signaling. Apoptosis. 2015;20:796–810. doi: 10.1007/s10495-015-1122-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mullonkal CJ, Toledo-Pereyra LH. Akt in ischemia and reperfusion. J Invest Surg. 2007;20:195–203. doi: 10.1080/08941930701366471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fujio Y, Nguyen T, Wencker D, Kitsis RN, Walsh K. Akt promotes survival of cardiomyocytes in vitro and protects against ischemia-reperfusion injury in mouse heart. Circulation. 2000;101:660–667. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.101.6.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Armstrong SC. Protein kinase activation and myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;61:427–436. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Surinkaew S, Kumphune S, Chattipakorn S, Chattipakorn N. Inhibition of p38 MAPK during ischemia, but not reperfusion, effectively attenuates fatal arrhythmia in ischemia/reperfusion heart. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2013;61:133–141. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e318279b7b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu SZ, Tao LY, Wang JN, Xu ZQ, Wang J, Xue YJ, Huang KY, Lin JF, Li L, Ji KT. Amifostine pretreatment attenuates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting apoptosis and oxidative stress. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:4130824. doi: 10.1155/2017/4130824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang P, Liu X, Huang G, Bai C, Zhang Z, Li H. Barbaloin pretreatment attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury via activation of AMPK. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;490:1215–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.06.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jones SP, Trocha SD, Lefer DJ. Pretreatment with simvastatin attenuates myocardial dysfunction after ischemia and chronic reperfusion. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:2059–2064. doi: 10.1161/hq1201.099509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen H, Liu S, Liu X, Yang J, Wang F, Cong X, Chen X. lysophosphatidic acid pretreatment attenuates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in the immature hearts of rats. Front Physiol. 2017;8:153. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ke Z, Liu J, Xu P, Gao A, Wang L, Ji L. The cardioprotective effect of icariin on ischemia-reperfusion injury in isolated rat heart: Potential involvement of the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway. Cardiovasc Ther. 2015;33:134–140. doi: 10.1111/1755-5922.12121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Skrzypiec-Spring M, Grotthus B, Szelag A, Schulz R. Isolated heart perfusion according to Langendorff-still viable in the new millennium. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2007;55:113–126. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Herr DJ, Aune SE, Menick DR. Induction and assessment of ischemia-reperfusion injury in langendorff-perfused rat hearts. J Vis Exp. 2015;27:e52908. doi: 10.3791/52908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Csonka C, Kupai K, Kocsis GF, Novák G, Fekete V, Bencsik P, Csont T, Ferdinandy P. Measurement of myocardial infarct size in preclinical studies. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2010;61:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.