Abstract

Background

We screened the potential molecular targets and investigated the molecular mechanisms of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Material/Methods

Microarray data of GSE47786, including the 40 μM berberine-treated HepG2 human hepatoma cell line and 0.08% DMSO-treated as control cells samples, was downloaded from the GEO database. Gene ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway (KEGG) enrichment analyses were performed; the protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks were constructed using STRING database and Cytoscape; the genetic alteration, neighboring genes networks, and survival analysis of hub genes were explored by cBio portal; and the expression of mRNA level of hub genes was obtained from the Oncomine databases.

Results

A total of 56 upregulated and 8 downregulated DEGs were identified. The GO analysis results were significantly enriched in cell-cycle arrest, regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent, protein amino acid phosphorylation, cell cycle, and apoptosis. The KEGG pathway analysis showed that DEGs were enriched in MAPK signaling pathway, ErbB signaling pathway, and p53 signaling pathway. JUN, EGR1, MYC, and CDKN1A were identified as hub genes in PPI networks. The genetic alteration of hub genes was mainly concentrated in amplification. TP53, NDRG1, and MAPK15 were found in neighboring genes networks. Altered genes had worse overall survival and disease-free survival than unaltered genes. The expressions of EGR1, MYC, and CDKN1A were significantly increased, but expression of JUN was not, in the Roessler Liver datasets.

Conclusions

We found that JUN, EGR1, MYC, and CDKN1A might be used as diagnostic and therapeutic molecular biomarkers and broaden our understanding of the molecular mechanisms of HCC.

MeSH Keywords: Berberine; Carcinoma, Hepatocellular; Hep G2 Cells

Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most prevalent forms of adult liver cancer and is the third leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide [1]. HCC accounts for over 80% of all liver cancers, with more than 600 000 people being diagnosed every year [2–4]. For patients, liver transplantation, surgical resection, and local ablation offer only limited options for HCC treatment [5]. However, due to surgical therapy limitations, advanced tumors can recur even after complete surgical resection; most patients with HCC are not suitable for surgical resection and fewer than 20% of patients respond to conventional chemotherapy [3]. Therefore, there is a need to develop effective new agents for HCC treatment.

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) provides important treatments for many diseases and depends on differentiation of TCM syndromes to inform therapy. Many herbal formulations in TCM are combined with conventional radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or surgical resection for the treatment of cancer, used alone or as an adjuvant therapy [3,6].

Berberine (BBR), a natural benzylisoquinoline alkaloid isolated from the Chinese herb Rizoma coptidis, has been reported to exhibit multiple pharmacological activities, such as anti-bacterial, anti-hypertensive, anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetic, and anti-hyperlipidemic effects, as well as anti-cancer effects [7–10]. Berberine is also known to possess potent anti-cancer activity in various cancer models, including gastric cancer, colon cancer, breast cancer, nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), and HCC [11]. The anti-tumor activity of berberine includes suppression of tumor cell proliferation, induction of tumor cell apoptosis, and inhibition of both tumor invasion and metastasis against a variety of human cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo [7,12,13]. Recently, berberine was confirmed to have anti-tumor effects to inhibit migration, invasion, metastasis and angiogenesis of HCC [14,15]. BBR may induce HCC cell apoptosis and autophagic cell death [14,16] and block the cell cycle [14,17]. These findings indicated that berberine is a promising candidate for clinical use in cancer chemotherapy. However, the exact biological targets of therapeutic intervention in tumor progression remain unclear.

In the present study, we further investigated the mRNA expression profile of 4-h treatment with 40 μM berberine in a hepatoblastoma cell line (HepG2) by re-analyzing the data of Lo et al. [18], which were deposited in in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. Cells were treated with 40 μM berberine chloride or 0.08% DMSO as control. We further screened the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between BBR and control group with a cut-off value of 0.05 for statistical significance and |log2fold change (FC)| ≥1. Then, the gene ontology (GO) and Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses were performed. The protein–protein interaction (PPI) network of DEGs were also constructed and identified the hub genes in the PPI network with front value of degree, node betweenness, and closeness via network topology calculation. The genetic alteration, neighboring genes networks, and survival analysis of hub genes were explored by cBio portal, and the expression of mRNA level of hub genes was obtained from the Oncomine databases. Our study was performed to provide a systematic perspective on understanding the molecular mechanism of HCC and to identify more novel potential therapeutic targets for HCC therapy.

Material and Methods

Microarray data information and identification of DEGs

The gene expression profile of GSE47786, based on the platform of GPL10558 (Illumina HumanHT-12 V4.0 expression BeadChip) (Illumina Inc, Santiago, CA, USA) and deposited by Lo et al. [18], were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database in National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). A 50 -M stock solution of berberine chloride was prepared in DMSO and the GSE47786 available in this study contained 2 cell samples (GSM1159672 and GSM1159671), including 40 μM berberine-treated HepG2 human hepatoma cell line and 0.08% DMSO-treated cells as control. Data in a SOFT-formatted family file were downloaded. Then, log2fold change (log2FC) was calculated to identify genes with expression-level differences. |log2FC|≥1.0 and adjusted P value <0.05 were used as the cut-off criteria for the DEGs.

Gene ontology (GO) and pathway enrichment analysis

Functional annotation of massive genes frequently has used GO analysis [19,20]. DEGs functions and pathways enrichment were analyzed using an online database, the Molecule Annotation System (MAS3.0), which is a Web-based software toolkit for a whole-data mining and function annotation solution to extract and analyze relationships among biological molecules from public knowledge bases of biological molecules. In our study, MAS3.0 was used for GO enrichment analysis to identify the significantly enriched biological process (BP) terms, molecular function (MF), and cellular component (CC), as well as for KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs, with P<0.05 as the cut-off criterion.

PPI network construction and hub genes identification

The Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING, http://www.string-db.org/) identifies the interactions of gene products, providing experimental and predicted interaction information [19,21]. In e present study, the interaction associations of the proteins were analyzed using STRING and the required confidence (combined score) ≥0.4 was used as the cut-off criterion [22,23]. Then, Cytoscape was used to visualize the network. Subsequently, the Network Analyzer plug-in was used to calculate node degree, node betweenness, and closeness. Degree stands for the number of inter-connections to filter hub genes of PPI in a network [24]. Node betweenness reflects the capability of nodes to manage the rate of information flow in the network [25]. Closeness is the inverse of the sum of the distance from a node to other nodes [26]. Higher scores for these 3 indices mean that the node is more central in the network. Therefore, the central nodes might be the core proteins and key candidate genes that have important physiological regulatory functions in HCC.

Exploring cancer genomics data linked to berberine by cBio Cancer Genomics Portal

The cBio Cancer Genomics Portal (http://cbioportal.org) is an open-access Web resource for exploring, visualizing, and analyzing multidimensional cancer genomics datasets, which provides graphical summaries of gene-level data from multiple platforms, network visualization and analysis, survival analysis, patient-centric queries, and software programmatic access to significantly lower the barriers between complex genomic data and cancer researchers, and enables researchers to translate these rich datasets into biologic insights and clinical applications [27,28]. In the present study, we used the cBio Cancer Portal to investigate the candidate genes across all hepatocellular carcinoma studies available in the database. The genomics datasets were then presented using OncoPrint as heatmaps, a concise and compact graphical summary of genomic alterations in multiple genes and multiple visualization networks that are altered in cancer. Survival analyses were performed by grouping hepatocellular carcinoma data alterations using input from berberine gene sets.

Analysis of hub genes expression in human HCC

Expression of hub genes in human HCC was determined through analysis of Roessler Liver databases, which are available through Oncomine (Compendia Biosciences, www.oncomine.org). Oncomine is a powerful Web application that integrates and unifies high-throughput cancer profiling data so that target expression across a large number of cancer types and experiments can be accessed online. We chose filter for the analysis type of cancer vs. normal, cancer type of hepatocellular carcinoma, sample type of clinical specimen, threshold by P VALUE for 1E-4, and fold change ≥2 and data type of mRNA to investigate the clinical significances in HCC.

Results

Identification of DEGs in hepatocellular carcinoma cell line

In total, 64 DEGs were screened out in HepG2 with berberine-treated compared with control group, in which 56 DEGs were upregulated and 8 DEGs were downregulated by using P<0.05 and |log2FC|≥1.0 as cut-off criterion. All the significantly upregulated and downregulated DEGs are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

64 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified in the HepG2 with 40μM berberine-treated, compared to 0.08% DMSO-treated as control cells sample.

| DEGs | Genes symbol |

|---|---|

| Up-regulated | ACTA1, ACTG1, AKR1C2, ANKRD1, BRWD1, C8ORF4, CBX4, CCL20, CDKN1A, CHMP1B, CTGF, CYR61, DDIT3, DUSP1, DUSP5, EGR1, ERRFI1, FOXQ1, FST, GADD45B, GDF15, HAMP, HES1, IER3, IGFBP1, IL8, JAG1, JUN, JUNB, KLF6, LOC648256, LOC648517, LOC88523, MIXL1, MT2A, MYC, N4BP2L2, NEDD9, NR0B2, NUAK2, PHLDA1, PIM1, PIM3, PPP1R15A, RASD1, SERTAD2, SLC25A25, SLC30A1, SPRY4, TAGLN, THBS1, TRIB1, TUFT1, WEE1, ZFP36, ZFP36L1 |

| Down-regulated | C20ORF177, EIF5, GPAM, GPER, NBPF20, TRIM25, TXNIP, ZC3HAV1 |

Functional enrichment analysis

GO functions enrichment analysis and KEGG pathways enrichment analysis were performed using Molecule Annotation System (MAS3.0) to further explore the biological molecular information of DEGs. The DEGs were classified into 3 functional groups: the biological process group, the molecular function group, and the cellular component group. As shown in Table 2. The results indicated the significantly enriched GO terms for biological process were cell cycle arrest, regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent, protein amino acid phosphorylation, and anti-apoptosis. The significantly enriched GO terms for molecular functions were protein binding, transcription factor activity, ATP binding, and nucleotide binding. The significantly enriched GO terms for cellular component were cytoplasm, nucleus, extracellular region, and cytosol.

Table 2.

Top 10 most significantly enriched GO terms of DEGs in HepG2.

| GO ID | GO term | p-Value | q-Value | Gene Symbol |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological process | ||||

| GO: 0007050 | Cell cycle arrest | 6.24E-14 | 2.12E-13 | CDKN1A; DDIT3; IL8; MYC; PPP1R15A; THBS1 |

| GO: 0006355 | Regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent | 6.62E-11 | 1.02E-10 | CBX4; DDIT3; EGR1; FOXQ1; HES1; JUN; KLF6; MIXL1; NR0B2; TXNIP |

| GO: 0006468 | Protein amino acid phosphorylation | 7.64E-09 | 8.66E-09 | CDKN1A; NUAK2; PIM1; PIM3; TRIB1; WEE1 |

| GO: 0006916 | Anti-apoptosis | 7.83E-08 | 7.16E-08 | CBX4; IER3; MYC; THBS1 |

| GO: 0000122 | Negative regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter | 8.00E-08 | 7.16E-08 | EGR1; FST; HES1; NR0B2 |

| GO: 0045944 | Positive regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter | 2.23E-07 | 1.90E-07 | EGR1; HES1; JUN; MYC |

| GO: 0007155 | Cell adhesion | 6.23E-07 | 5.04E-07 | CTGF; CYR61; HES1; NEDD9; THBS1 |

| GO: 0007275 | Development | 7.63E-07 | 5.90E-07 | CDKN1A; FST; GADD45B; JAG1; MIXL1; PIM1; SPRY4 |

| GO: 0007049 | Cell cycle | 1.12E-06 | 7.78E-07 | DDIT3; DUSP1; NEDD9; WEE1; TXNIP |

| GO: 0006915 | Apoptosis | 1.14E-06 | 7.78E-07 | C8ORF4; GADD45B; IER3; PHLDA1; PPP1R15A |

| Molecular function | ||||

| GO: 0005515 | Protein binding | 8.58E-27 | 8.58E-27 | ACTA1; ANKRD1; BRWD1; CTGF; DUSP1; ERRFI1; FST; GADD45B; IER3; IL8; JAG1; MT2A; MYC; NEDD9; PHLDA1; PIM1; PIM1; PPP1R15A; RASD1; SERTAD2; SPRY4; TAGLN; WEE1; ZFP36; ZFP36L1; TRIM25; TXNIP |

| GO: 0003700 | Transcription factor activity | 7.95E-15 | 7.95E-15 | DDIT3; EGR1; FOXQ1; JUN; JUNB; MIXL1; MYC; NR0B2; ZFP36L1; TRIM25 |

| GO: 0005524 | ATP binding | 1.04E-11 | 1.04E-11 | ACTA1; ACTG1; CDKN1A; NUAK2; PIM1; PIM1; PIM3; TRIB1; WEE1 |

| GO: 0000166 | Nucleotide binding | 1.58E-11 | 1.58E-11 | ACTA1; ACTG1; CDKN1A; NUAK2; PIM1; PIM1; PIM3; RASD1; WEE1; EIF5 |

| GO: 0008270 | Zinc ion binding | 5.68E-11 | 5.68E-11 | CDKN1A; DUSP1; EGR1; KLF6; MT2A; SLC30A1; ZFP36; ZFP36L1; TRIM25; ZC3HAV1 |

| GO: 0003714 | Transcription corepressor activity | 6.43E-11 | 6.43E-11 | ANKRD1; CBX4; DDIT3; JUNB; NR0B2 |

| GO: 0046872 | Metal ion binding | 8.63E-10 | 8.63E-10 | CDKN1A; DUSP1; EGR1; JUNB; KLF6; MT2A; PIM1; ZFP36; ZFP36L1; TRIM25; ZC3HAV1 |

| GO: 0043565 | Sequence-specific DNA binding | 1.67E-09 | 1.67E-09 | DDIT3; FOXQ1; JUNB; MIXL1; MYC; PIM1 |

| GO: 0005520 | Insulin-like growth factor binding | 2.15E-08 | 2.15E-08 | CTGF; CYR61; IGFBP1 |

| GO: 0004674 | Protein serine/threonine kinase activity | 3.07E-08 | 3.07E-08 | CDKN1A; NUAK2; PIM1; PIM3; WEE1 |

| Cellular component | ||||

| GO: 0005737 | Cytoplasm | 1.91E-33 | 1.91E-33 | ACTA1; ACTG1; AKR1C2; ANKRD1; BRWD1; CDKN1A; CHMP1B; DDIT3; ERRFI1; HES1; KLF6; MYC; MYC; NEDD9; PHLDA1; PIM1; PIM1; SERTAD2; SPRY4; TAGLN; TRIB1; TUFT1; ZFP36; ZFP36L1; EIF5; NBPF20; NBPF20; NBPF20; TRIM25; TXNIP; ZC3HAV1 |

| GO: 0005634 | Nucleus | 1.26E-32 | 1.26E-32 | ANKRD1; BRWD1; CBX4; CDKN1A; DDIT3; DUSP1; DUSP5; EGR1; FOXQ1; HES1; JUN; JUNB; JUNB; KLF6; MIXL1; MYC; MYC; NEDD9; NR0B2; PHLDA1; PIM1; SERTAD2; TRIB1; WEE1; ZFP36; ZFP36L1; TRIM25; ZC3HAV1 |

| GO: 0005576 | Extracellular region | 6.44E-13 | 6.44E-13 | CCL20; CTGF; CYR61; FST; GDF15; HAMP; IGFBP1; IL8; JAG1; THBS1; TUFT1 |

| GO: 0005829 | Cytosol | 1.23E-09 | 1.23E-09 | CDKN1A; JUN; MYC; ZFP36; ZFP36L1; EIF5; GPAM |

| GO: 0005615 | Extracellular space | 6.07E-06 | 6.07E-06 | CCL20; GDF15; IGFBP1; IL8 |

| GO: 0005886 | Plasma membrane | 1.04E-05 | 1.04E-05 | CTGF; JAG1; PIM1; RASD1; SLC30A1; SPRY4; GPER |

| GO: 0005739 | Mitochondrion | 6.57E-05 | 6.57E-05 | HES1; PIM1; SLC25A25; GPAM |

| GO: 0005819 | Spindle | 1.91E-04 | 1.91E-04 | MYC; NEDD9 |

| GO: 0000785 | Chromatin | 4.50E-04 | 4.50E-04 | CBX4; JUNB |

| GO: 0005667 | Transcription Factor Complex | 5.00E-04 | 5.00E-04 | ANKRD1; JUN |

KEGG pathways enrichment analysis suggests that berberine-associated genes in the HepG2 are mainly linked to cancer-related and signaling cascade pathways as potential molecular mechanisms, including control of cancer cell proliferation and survival via MAPK/p53-mediated cell cycle control, and regulation of gene transcription by Wnt signaling pathway, and various cancers were also found to be significantly enriched (Table 3).

Table 3.

Top 20 Enriched KEGG pathways for DEGs in HepG2.

| KEGG term | p-Value | q-Value | Gene symbol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bladder cancer | 1.25E-07 | 1.13E-07 | CDKN1A; IL8; MYC; THBS1 |

| MAPK signaling pathway | 4.99E-07 | 1.49E-07 | DDIT3; DUSP1; DUSP5; GADD45B; JUN; MYC |

| ErbB signaling pathway | 2.41E-06 | 4.38E-07 | CDKN1A; JUN; MYC |

| p53 signaling pathway | 5.73E-05 | 4.78E-06 | CDKN1A; GADD45B; THBS1 |

| Focal adhesion | 7.05E-05 | 5.42E-06 | ACTG1; CDKN1A; JUN; THBS1 |

| TGF-beta signaling pathway | 1.14E-04 | 7.53E-06 | FST; MYC; THBS1 |

| Cell cycle | 2.89E-04 | 1.34E-05 | CDKN1A; GADD45B; WEE1 |

| Jak-STAT signaling pathway | 6.25E-04 | 2.40E-05 | MYC; PIM1; SPRY4 |

| Notch signaling pathway | 0.001175099 | 4.20E-05 | HES1; JAG1 |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 0.001844782 | 6.15E-05 | MYC; PIM1 |

| Epithelial cell signaling in Helicobacter pylori infection | 0.002584386 | 7.71E-05 | IL8; JUN |

| Renal cell carcinoma | 0.002657485 | 7.82E-05 | CDKN1A; JUN |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 0.002959542 | 8.46E-05 | CDKN1A; MYC |

| Colorectal cancer | 0.00369512 | 9.99E-05 | JUN; MYC |

| Toll-like receptor signaling pathway | 0.005393581 | 1.32E-04 | IL8; JUN |

| T cell receptor signaling pathway | 0.006133955 | 1.46E-04 | CDKN1A; JUN |

| Wnt signaling pathway | 0.011615736 | 2.08E-04 | JUN; MYC |

| Regulation of actin cytoskeleton | 0.022897149 | 2.76E-04 | ACTG1; CDKN1A |

| Maturity onset diabetes of the young | 0.025366415 | 2.90E-04 | HES1 |

| Thyroid cancer | 0.03057119 | 3.27E-04 | MYC |

PPI network analysis

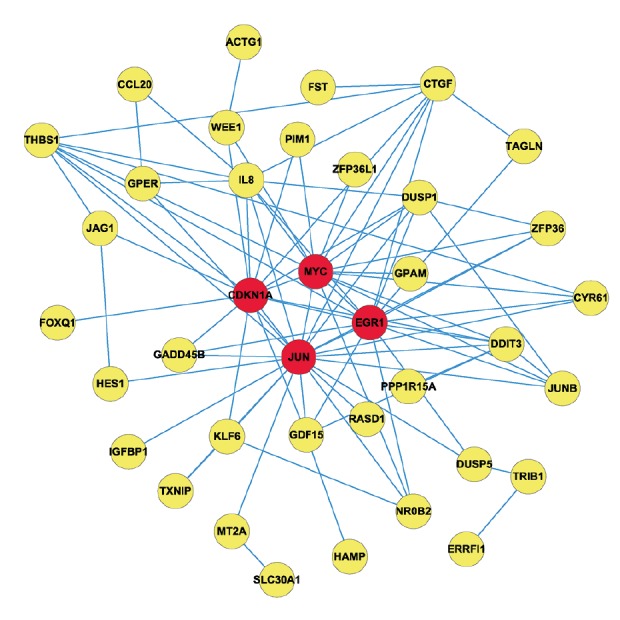

The PPI network for the DEGs between berberine-treated HepG2 human hepatoma cell line and 0.08% DMSO-treated as control cells are shown in Figure 1. The PPI network was constructed with 38 nodes and 87 edges. Among the 38 nodes, 4 central node genes (red in Figure 2) were identified with the filtering of degree >10 criteria, and the most significant 4 node degree genes were JUN (degree=22, Node betweenness=0.446, Closeness=0.685), EGR1 (degree=16, Node betweenness=0.135, Closeness=0.606), MYC (degree=16, Node betweenness=0.196, Closeness=0.587), and CDKN1A (degree=15, Node betweenness=0.182, Closeness=0.587). Thus, based on the results of functional analysis combined with the PPI network analysis, we selected the 4 node genes acting as the hub genes in HepG2 for subsequent study.

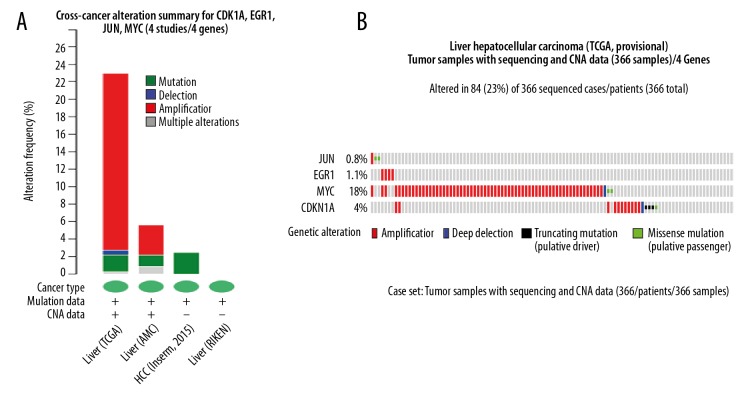

Figure 1.

Exploring genetic alterations connected with berberine-treated HepG2-associated genes, JUN, EGR1, MYC, and CDKN1A in hepatocellular carcinoma by cBio portal. (A) Summary of changes on JUN, EGR1, MYC, and CDKN1A genes in genomics data sets available in 4 different hepatocellular carcinoma studies. (B) OncoPrint: A visual summary of alteration across a set of hepatocellular carcinoma samples (data taken from the TCGA Data Portal) based on a query of the 4 genes JUN, EGR1, MYC, and CDKN1A). Distinct genomic alterations are summarized and color-coded, presented by% changes in particular affected genes in individual tumor samples. Each row represents a gene and each column represents a tumor sample. Red bars designate gene Amplifications, blue bars represent Deep Deletion, black stand for Truncating Mutation (putative driver) and green squares indicate Missense Mutation (putative passenger).

Figure 2.

Protein–protein interaction network for the differentially expressed genes in HepG2. Nodes stand for proteins and edges represent interactions between 2 proteins. Red color nodes represent the central nodes.

Exploring genetic alterations connected with berberine-treated HepG2-associated genes JUN, EGR1, MYC and CDKN1A in hepatocellular carcinoma by cBio portal

Combining the result of functional analysis and PPI network topological structure calculation indicated that JUN, EGR1, MYC, and CDKN1A may play a role in hepatocellular carcinoma. To further explore the relationship between hub genes and hepatocellular carcinoma, cBio portal, a Web-based integrated data mining system, was used to cross-explore their cancer clinical profiles and genomic alterations in hepatocellular carcinoma. Among 4 hepatocellular carcinomas analyzed, alterations ranging from 2.5% to 23% were found for the gene sets submitted for analysis (Figure 1A). A summary of the multiple gene alterations observed across each set of tumor samples from the TCGA Data Portal showing the most pronounced genomic changes is presented using OncoPrint. As shown in Figure 1B, the results show that 84 cases (23%) had an alteration in at least 1 of the 4 genes queried. For JUN, 2 samples of gene alteration occurred for Missense Mutation (Figure 1B), and only amplification occurred in EGR1 (Figure 1B). For MYC and CDKN1A, most alterations were classified as amplification with a few cases of Deep Deletion, Truncating Mutation, and Missense Mutation (Figure 1B).

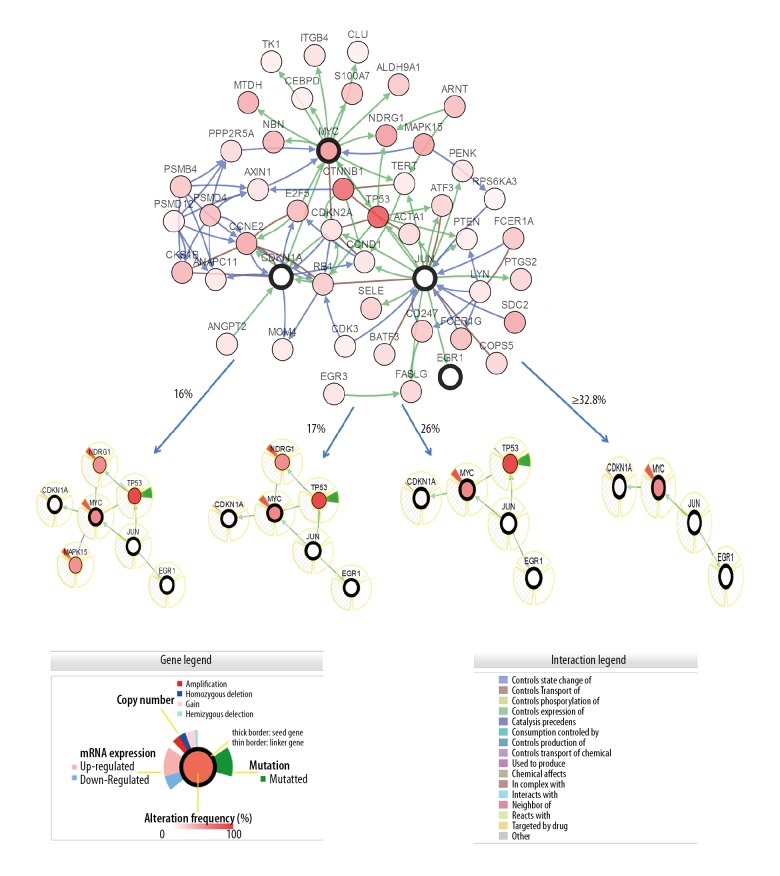

Multiple visualization networks were generated in the cBio portal to investigate the potential of complexity as well as the variability of difference in interactions between hub genes most relevant to the genes altered in hepatocellular carcinoma tumor samples from the TCGA Data Portal. The genomic alteration frequency was applied as a filter to show the neighbors with the highest alteration frequency. The cBio portal construct network contains all neighbors of 4 query genes: JUN, EGR1, MYC, and CDKN1A (Figure 3). The 4 hub genes were identified when neighbors’ ≥32.8% alteration was applied as the filter (Figure 3). Using a filter of 26% alteration, TP53 were revealed (Figure 3). A 6-gene cluster with TP53 and NDRG1 was observed with a filter incorporating a 17% alteration (Figure 3) and including MAPK15 in a 7-gene cluster when the filter was reduced to 16% alteration (Figure 3). The results of interactive analysis give insights into the role of berberine in the prevention of treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma by interacting with multiple targets. The identified hub genes across samples in large-scale cancer genomics projects find genetic alterations by querying multidimensional cancer genomics data embedded in the cBio portal.

Figure 3.

Neighboring gene display connected to JUN, EGR1, MYC, and CDKN1A in hepatocellular carcinoma (based on the TCGA Data Portal). JUN, EGR1, MYC, and CDKN1A are used as seed genes (indicated with thick black border) to automatically harvest all other genes identified as altered in hepatocellular carcinoma. Multidimensional genomic details are shown for seed genes JUN, EGR1, MYC, and CDKN1A. Darker red indicates increased frequency of alteration (defined by mutation, copy number amplification, or homozygous deletion) in hepatocellular carcinoma. The figure shows the full and pruned network containing all or partial neighbors of all query genes generated; neighboring gene connected to JUN, EGR1, MYC, and CDKN1A as filtered by alterations (%).

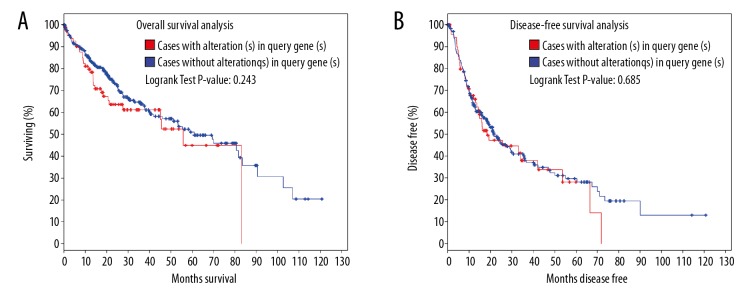

The cBio portal also provides survival analysis to view genes that are altered in cancer. Overall survival and disease-free differences are computed between tumor samples that have at least 1 alteration in 1 of the query genes and tumor samples that do not. The results are displayed as Kaplan-Meier plots with P values from a log-rank test [27,28]. As shown in Figure 4, cases with one of the query genes alteration have worse overall survival and disease-free survival than cases without one of the query genes alteration, although both had shown no difference with P value 0.243 and 0.685 in the present study. Hence, additional research is required to confirm the characteristics of JUN, EGR1, MYC, and CDKN1A in the human HCC line (HepG2).

Figure 4.

The survival analysis shows the overall survival (A) and the disease-free survival (B) of hepatocellular carcinoma patients with or without JUN, EGR1, MYC, or CDKN1A mutations. The red curves in the Kaplan-Meier plots include all tumors with a JUN, EGR1, MYC, or CDKN1A germline or somatic mutation, and the blue curves include all samples without a JUN, EGR1, MYC, or CDKN1A mutation.

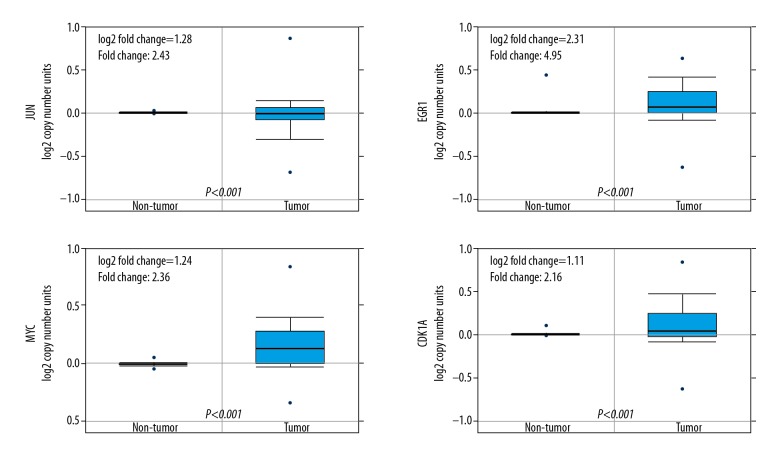

Expression of JUN, EGR1, MYC, and CDKN1A in human HCC based on Oncomine database

To determine the clinical significances of JUN, EGR1, MYC, and CDKN1A in patients with HCC, we performed data mining and analyzed JUN, EGR1, MYC, and CDKN1A expressions from the publicly available Oncomine database. The finding suggested that the expression of JUN is significantly weaker in HCC specimens compared with normal liver samples, but EGR1, MYC, and CDKN1A are the opposite (Figure 5). The hub genes were upregulated respond to berberine with the dose of 40 μM in the microarray. It indicated that JUN, EGR1, MYC, and CDKN1A probably play critical roles in the development of the HCC. Therefore, we intend to perform further experimental verifications in our future studies using different methods such as immunohistochemistry and quantitative RT-PCR to investigate the functions of JUN, EGR1, MYC, and CDKN1A and anti-cancer characteristics of berberine.

Figure 5.

Clinical significances of JUN, EGR1, MYC, and CDKN1A in HCC. Oncomine data mining showing JUN, EGR1, MYC, and CDKN1A mRNA expression levels in Roessler Liver datasets between normal vs hepatocellular carcinoma (n=97)

Discussion

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most frequently diagnosed malignancies, with very poor 5-year survival rates [29]. The elucidation of molecular mechanism of HCC onset and progression has long been extensively pursued but remain mostly elusive. In this study, the gene expression profile data of GSE47786 were downloaded from the GEO database to re-analyzed DEGs between 40 μM berberine-treated HepG2 human hepatoma cell line and 0.08% DMSO-treated as a control cells sample using bioinformatics and PPI analysis to further investigate the pathogenesis and explore the molecular therapeutic targets for HCC. A total of 64 DEGs, including 56 upregulated and 8 downregulated genes, with P<0.05 and |log2FC|≥1.0 were selected. Furthermore, the GO enrichment analysis results showed that 64 DEGs were related to cell cycle arrest, regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent, cell cycle, and apoptosis. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis indicated that MAPK/p53, cell cycle, and Wnt signaling pathway might be involved in the development of HCC. JUN, EGR1, MYC, and CDKN1A were hub nodes in the PPI network. Additionally, the results of genetic alterations mainly concentrated on amplification and survival analysis, showing the overall survival and the disease-free survival were worse when one of the query genes had genetic change. Therefore, these hub genes may be involved in HCC progression.

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has been used worldwide as a complementary and alternative medicine to treat cancer in recent decades. Many studies have shown that BBR possesses inhibitive effects for suppressing human cancer cell growth via suppression of tumor cell proliferation, induction of tumor cell apoptosis, and inhibition of both invasion and metastasis in vitro and in vivo [30]. BBR inhibits proliferation and migration and induces G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in HCC [30,31]. For example, Chu et al. reported that berberine inhibited the viability, migration, and invasion capacity of HepG2 cells through the induction of pyroptosis, at least partially through the activation of caspase-1 [32]. Wang et al. demonstrated that berberine exhibits dose- and time-dependent inhibition of Cyclin D1 expression in human hepatoma cell HepG2 to attenuate cancer cell resistance to chemotherapeutic agents [33]. However, further information on the molecular targets underlying the anti-cancer efficacy of berberine has not been fully elucidated. In the present study, JUN, EGR1, MYC, and CDKN1A were identified as central nodes in the PPI network, which suggests that they may be worth further study under certain conditions.

Cellular JUN Proto-oncogene (c-JUN), together with c-fos, is a component of transcription factor AP-1, which is a transcription factor implicated in the induction of gene transcription by phorbol ester tumor promoters [34]. AP-1 directs the expression of cyclin D1, a member of the G1 cyclin family involved in the regulation of the G1/S transition of the cell cycle, which may facilitate the development of invasive cancer for uncontrolled proliferation in normal human cells when it accumulates continuously in nuclei [35,36]. Luo et al. found that berberine inhibits cyclin D1 expression through suppression of c-JUN expression, thereby significantly suppressing AP-1 transcriptional activity [37]. c-JUN acts as Janus Kinase (JNK) substrate and induced DNA damage that regulates cell proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation. From the visualization networks in the cBio portal, we found that JUN interacts with TP53. Previous studies have reported that a major function of c-JUN in cell-cycle cells progression and liver tumorigenesis is preventing apoptosis by antagonizing p53 activity, contributing to early-stage HCC [38]. We noted that the expression of JUN in tumor samples was lower than in normal samples in Roessler Liver datasets on Oncomine database, which is inconsistent with previous studies. Berberine upregulated the expression of JUN under our experimental conditions in the present study, which we speculated optimized conditions, and validations in HepG2 should be considered in further studies.

Early growth response gene-1 (EGR1) is a nuclear zinc-finger transcription factor that belongs to a family of early response genes with an amino terminal activation domain consisting of 3 cys2–his2 zinc fingers near the carboxy terminal end of the protein sequence [39,40]. Increasing evidence indicates that EGR1 plays positive and negative functions in different types of cancers, relying on the integrated functions of various genes it regulates. For instance, Park et al. reported that EGR1 regulates cathepsin D to promote the invasion ability in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells [41]. In addition, Peng et al. demonstrated EGR1 contributes to HCC radioresistance through directly upregulating target gene Atg4B [42]. Paradoxically, the expression of the EGR1 was upregulated for β-lapachone to inhibit the progression and metastasis of hepatoma cells [43]. Similarly, induction of apoptosis, inhibitions of cell proliferation, and cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase were observed in HepG2 cells treated with berberine through increased NAG-1 promoter activity preceded by the elevation of Egr-1/DNA binding activity [44]. Evidence also indicates that EGR1 inhibits cell growth, proliferation, and metastasis, and induces apoptosis via directly or indirectly upregulating multiple tumor suppressors PTEN, TP53, fibronectin, BCL-2, and TGFβ1, which act as a tumor repressor and tumor suppressor in non-small-cell lung carcinoma by regulating KRT18 expression [45,46]. In this study, we showed that EGR1 is upregulated in microarray by BBR treatment in HCC cells, which indicates that BBR can improve the expression of EGR1 under the experimental condition in this study. We found that the expression of EGR1 in tumor samples was higher than in normal samples in the Roessler Liver datasets in the Oncomine database, and more clinical samples are needed for validation in further studies.

c-MYC, a synonym of Homo sapiens v-myc myelocytomatosis viral oncogene homolog (MYC) oncoprotein, known to control cell cycle progression, proliferation, growth, adhesion, differentiation, apoptosis, and metabolism, was discovered over 35 years ago [3,47–49]. The transcription factor c-MYC was one of the first oncogenes identified for its high expression levels [50]. The mRNA expression level of MYC was significantly higher than in normal samples in the Roessler Liver datasets, consistent with previous studies. Simile et al. showed that c-MYC down-regulation is capable of inhibiting cell cycle activity and growth of both human HepG2 and rodent Morris 5123 liver cancer cells [51]. MYC has been shown to contribute to cell proliferation and tumorigenesis, which directly increase the expression of E2F, as well as cyclin-D and cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 4, and then activates cyclin-E and CDK2 via sequestration of p27 [52]. miRNAs are a diverse class of highly evolutionally conserved small RNAs that regulate the transcription and translation of genes. Previous studies showed that HCC cell growth was regulated by miRNAs like miR-101, miR-221, miR-224, miR-195, miR-122, miR-223, miR-21, and miR-199. Meng et al. showed that miR-33a-5p overexpression increased the cisplatin sensitivity of HCC cells [53]. Song et al. demonstrated that miR-4417 targets TRIM35 and regulates the Y105 phosphorylation of PKM2 to promote cell proliferation and inhibit apoptosis in HCC cells [54], and Xie F et al. also reported that miR-320a as a tumor suppressor inhibits tumor proliferation and invasion by directly targeting c-MYC in hepatocellular carcinoma [55]. However, the gene expression level of MYC was upregulated by 4-h treatment with 40-μM BBR in the present study. Hence, further studies are needed to clarify the role of MYC and the molecular mechanisms of growth inhibition in hepatoma cells exposed to BBR.

Cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor p21, also known as p21waf1/cip1 or P21/CDKN1A [56,57], is a well-known inhibitor of cell cycle and can arrest the cell cycle progression in G1/S and G2/M transitions by inhibiting CDK4, 6/cyclin-D, and CDK2/cyclin-E [57,58]. The molecular behavior of p21 depends on its subcellular localization. Nuclear p21 may inhibit cell proliferation and be pro-apoptotic in a p53-dependent or -independent manner, while cytoplasmic p21 may have oncogenic and anti-apoptotic functions [59]. Recent reports demonstrate that BBR treatment induced cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase by upregulating protein expression of p53 and p21, the tumor-suppressor gene [30,60]. However, the result of the expression of CDKN1A in tumor samples were higher than in normal samples in Roessler Liver datasets in the Oncomine database, which is contrary to previous studies and needs further studies with larger sample sizes. In this study, BBR improved the gene expression level of CDKN1A (P21 protein), which is consistent with the cell cycle arrest function and indicted that CDKN1A could be a therapeutic target for HCC.

Conclusions

JUN, EGR1, MYC and CDKN1A may be potential target genes for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. The present study augments our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the effect of BBR on human hepatoma cell HepG2. Bioinformatics analysis is a useful strategy from a new perspective to explore cancer. Further experimental studies with larger sample sizes are required to validate the effects and mechanisms of JUN, EGR1, MYC, and CDKN1A in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Chong Yang at the Department of General Surgery of Hangzhou Red Cross Hospital for technical discussions and assistance.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

Source of support: Departmental sources

References

- 1.Chen J, Wu FX, Luo HL, et al. Berberine upregulates miR-22-3p to suppress hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation by targeting Sp1. Am J Transl Res. 2016;8:4932–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu R, Zhang Z, Wang B, et al. Berberine-induced apoptotic and autophagic death of HepG2 cells requires AMPK activation. Cancer Cell Int. 2014;14:49. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-14-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chou ST, Hsiang CY, Lo HY, et al. Exploration of anti-cancer effects and mechanisms of Zuo-Jin-Wan and its alkaloid components in vitro and in orthotopic HepG2 xenograft immunocompetent mice. BMC Complem Altern. 2017;17:121. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1586-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yim HJ, Suh SJ, Um SH. Current management of hepatocellular carcinoma: An Eastern perspective. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(13):3826–42. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i13.3826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ting CT, Li WC, Chen CY, et al. Preventive and therapeutic role of traditional Chinese herbal medicine in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Chin Med Assoc. 2015;78:139–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gavaraskar K, Dhulap S, Hirwani RR. Therapeutic and cosmetic applications of Evodiamine and its derivatives – A patent review. Fitoterapia. 2015;106:22–35. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2015.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hou Q, Tang X, Liu H, et al. Berberine induces cell death in human hepatoma cells in vitro by downregulating CD147. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1287–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.01933.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cui HM, Zhang QY, Wang JL, et al. In vitro studies of berberine metabolism and its effect of enzyme induction on HepG2 cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;158:388–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li M, Zhang M, Zhang Z, et al. Induction of apoptosis by berberine in hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells via downregulation of NF-κB. Oncol Res. 2017;25(2):233–39. doi: 10.3727/096504016X14742891049073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yan XJ, Yu X, Wang XP, et al. Mitochondria play an important role in the cell proliferation suppressing activity of berberine. Sci Rep. 2017;7:41712. doi: 10.1038/srep41712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsang CM, Cheung KCP, Cheung YC, et al. Berberine suppresses Id-1 expression and inhibits the growth and development of lung metastases in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852:541–51. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun Y, Xun K, Wang Y, et al. A systematic review of the anticancer properties of berberine, a natural product from Chinese herbs. Anticancer Drugs. 2009;20:757–69. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e328330d95b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang J, Feng Y, Tsao S, et al. Berberine and Coptidis rhizoma as novel antineoplastic agents: A review of traditional use and biomedical investigations. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;126:5–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X, Wang N, Li H, et al. Up-regulation of PAI-1 and down-regulation of uPA are involved in suppression of invasiveness and motility of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by a natural compound berberine. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:577. doi: 10.3390/ijms17040577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jie S, Li H, Tian Y, et al. Berberine inhibits angiogenic potential of HepG2 cell line through VEGF down-regulation in vitro. J. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:179–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lopes Barreto D, Struijk DG, Krediet RT. Peritoneal effluent MMP-2 and PAI-1 in encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65:748–53. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan YL, Goh D, Ong ES. Investigation of differentially expressed proteins due to the inhibitory effects of berberine in human liver cancer cell line HepG2. Mol Biosyst. 2006;2:250–58. doi: 10.1039/b517116d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lo TF, Tsai WC, Chen ST. MicroRNA-21-3p, a berberine-induced miRNA, directly down-regulates human methionine adenosyltransferases 2A and 2B and inhibits hepatoma cell growth. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75628. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Y, Teng L, Liu W, et al. Identification of biological targets of therapeutic intervention for clear cell renal cell carcinoma based on bioinformatics approach. Cancer Cell Int. 2016;16:16. doi: 10.1186/s12935-016-0291-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, et al. Gene Ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franceschini A, Szklarczyk D, Frankild S, et al. STRING v9.1: protein–protein interaction networks, with increased coverage and integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:808–15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saito R, Smoot ME, Ono K, et al. A travel guide to Cytoscape plugins. Nat Methods. 2012;9:1069–76. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu X, Shi Z, Hu J, et al. Identification of differentially expressed genes associated with burn sepsis using microarray. Int J Mol Med. 2015;36:1623–29. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2015.2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Missiuro PV, Liu K, Zou L, et al. Information flow analysis of interactome networks. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raman K, Damaraju N, Joshi GK. The organizational structure of protein networks: Revisiting the centrality-lethality hypothesis. Syst Synth Biology. 2014;8:73–81. doi: 10.1007/s11693-013-9123-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y, Bai M, Zhang B, et al. Uncovering pharmacological mechanisms of Wu-tou decoction acting on rheumatoid arthritis through systems approaches: drug-target prediction, network analysis and experimental validation. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9463. doi: 10.1038/srep09463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: An open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:401–4. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal. 2013;6:pl1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chuang TY, Wu HL, Min J, et al. Berberine regulates the protein expression of multiple tumorigenesis-related genes in hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Cell Int. 2017;17(1):59. doi: 10.1186/s12935-017-0429-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang N, Zhu M, Wang X, et al. Berberine-induced tumor suppressor p53 up-regulation gets involved in the regulatory network of MIR-23a in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1839:849–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chu Q, Jiang Y, Zhang W, et al. Pyroptosis is involved in the pathogenesis of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:84658. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang N, Wang X, Tan HY, et al. Berberine suppresses cyclin D1 expression through proteasomal degradation in human hepatoma cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17 doi: 10.3390/ijms17111899. pii: E1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maeda S, Karin M. Oncogene at last – c-Jun promotes liver cancer in mice. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:102–4. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsushime H, Roussel MF, Ashmun RA, Sherr CJ. Colony-stimulating factor 1 regulates novel cyclins during the G1 phase of the cell cycle. Cell. 1991;65:701–13. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gautschi O, Ratschiller D, Gugger M, et al. L Cyclin D1 in non-small cell lung cancer: a key driver of malignant transformation. Lung Cancer. 2007;55:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luo Y, Hao Y, Li N. Berberine inhibits cyclin D1 expression via suppressed binding of AP-1 transcription factors to CCND1 AP-1 motif. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2008;29:628–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2008.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eferl R, Ricci R, Kenner L, et al. Liver tumor development. c-Jun antagonizes the proapoptotic activity of p53. Cell. 2003;112:181–92. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sukhatme VP, Cao X, Chang LC, et al. A zinc fingerencoding gene coregulated with c-fos during growth and differentiation, and after cellular depolarization. Cell. 1988;53:37–43. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90485-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang H, Chen X, Wang J, et al. EGR1 decreases the malignancy of human non-small cell lung carcinoma by regulating KRT18 expression. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5416. doi: 10.1038/srep05416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park YJ, Kim EK, Bae JY, et al. Human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) promotes cancer invasion by modulating cathepsin D via early growth response (EGR)-1. Cancer Lett. 2016;370:222–31. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peng W, Wan Y, Gong A, et al. Egr-1 regulates irradiation-induced autophagy through Atg4B to promote radioresistance in hepatocellular carcinoma cells Oncogenesis 20176e292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim SO, Kwon JI, Jeong YK, et al. Induction of Egr-1 is associated with anti-metastatic and anti-invasive ability of β-lapachone in human hepatocarcinoma cells. Biosc Biotechnol Biochem. 2007;71:2169–76. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Auyeung KKW, Ko JKS. Coptis chinensis inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma cell growth through nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-activated gene activation. Int J Mol Med. 2009;24:571–77. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang H, Chen X, Wang J, et al. EGR1 decreases the malignancy of human non-small cell lung carcinoma by regulating KRT18 expression. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5416. doi: 10.1038/srep05416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boone DN, Qi Y, Li Z, et al. Egr1 mediates p53-independent c-Myc – induced apoptosis via a noncanonical ARF-dependent transcriptional mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:632–37. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008848108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miller DM, Thomas SD, Islam A, et al. C-myc and cancer metabolism. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:5546–53. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dang CV. C-myc target genes involved in cell growth, apoptosis, and metabolism. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1–11. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zheng K, Cubero FJ, Nevzorova YA. c-MYC – making liver sick: Role of c-MYC in hepatic cell function, homeostasis and disease. Genes. 2017;8:123. doi: 10.3390/genes8040123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peng SY, Lai PL, Hsu HC. Amplification of the c-myc gene in human hepatocellular carcinoma: Biologic significance. J Formos Med Assoc. 1993;92:866–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simile MM, De Miglio MR, Muroni MR, et al. Down-regulation of c-myc and cyclin d1 genes by antisense oligodeoxy nucleotides inhibits the expression of e2f1 and in vitro growth of hepg2 and morris 5123 liver cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:333–41. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lutz W, Leon J, Eilers M. Contributions of Myc to tumorigenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1602:61–71. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(02)00036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meng W, Tai Y, Zhao H, et al. Downregulation of miR-33a-5p in hepatocellular carcinoma: A possible mechanism for chemotherapy resistance. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:1295–304. doi: 10.12659/MSM.902692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Song L, Zhang W, Chang Z, et al. miR-4417 targets tripartite motif-containing 35 (TRIM35) and regulates pyruvate kinase muscle 2 (PKM2) phosphorylation to promote proliferation and suppress apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:1741–50. doi: 10.12659/MSM.900296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xie F, Yuan Y, Xie L, et al. mirna-320a inhibits tumor proliferation and invasion by targeting c-Myc in human hepatocellular carcinoma. OncoTargets Ther. 2017;10:885–94. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S122992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abbas T, Dutta A. p21 in cancer: Intricate networks and multiple activities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:400–14. doi: 10.1038/nrc2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Karimian A, Ahmadi Y, Yousefi B. Multiple functions of p21 in cell cycle, apoptosis and transcriptional regulation after DNA damage. DNA Repair. 2016;42:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zaldua N, Llavero F, Artaso A, Gálvez P. Rac1/p21-activated kinase pathway controls retinoblastoma protein phosphorylation and E2F transcription factor activation in B lymphocytes. FEBS J. 2016;283:647–61. doi: 10.1111/febs.13617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ohkoshi S, Yano M, Matsuda Y. Oncogenic role of p21 in hepatocarcinogenesis suggests a new treatment strategy. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:12150. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i42.12150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eo SH, Kim JH, Kim SJ. Induction of G2/M arrest by berberine via activation of PI3K/Akt and p38 in human chondrosarcoma cell line. Oncol Res. 2015;22:147–57. doi: 10.3727/096504015X14298122915583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]